Abstract

Within the countries of the former Soviet Union, the Kyrgyz Republic has been a pioneer in reforming the system of health care finance. Since the introduction of its compulsory health insurance fund in 1997, the country has gradually moved from subsidizing the supply of services to subsidizing the purchase of services through the ‘single payer’ of the health insurance fund. In 2002 the government introduced a new co-payment for inpatients along with a basic benefit package. A key objective of the reforms has been to replace the burgeoning system of unofficial informal payments for health care with a transparent official co-payment, thereby reducing the financial burden of health care spending for the poor. This article investigates trends in out-of-pocket payments for health care using the results of a series of nationally representative household surveys conducted over the period 2001–2007, when the reforms were being rolled out. The analysis shows that there has been a significant improvement in financial access to health care amongst the population. The proportion paying state providers for consultations fell between 2004 and 2007. As a result of the introduction of co-payments for hospital care, fewer inpatients report making payments to medical personnel, but when they are made, payments are high, especially to surgeons and anaesthetists. However, although financial access for outpatient care has improved, the burden of health care payments amongst the poor remains significant.

Keywords: Informal payments, health financing, reform, Kyrgyzstan

KEY MESSAGES.

The proportion paying state providers for outpatient consultations has fallen between 2004 and 2007. However, although financial access for outpatient care has improved, the burden of health care payments amongst the poor remains significant.

As a result of the introduction of co-payments for hospital care, fewer inpatients report making payments to medical personnel but when they are made, payments are high, especially to surgeons and anaesthetists. The overall out-of-pocket costs of inpatient care have fallen and equity has improved.

Kyrgyzstan provides a model that could be replicated throughout the region.

Introduction

At independence, the Kyrgyz Republic inherited a health system with universal access and services free at the point of delivery. In common with other countries of the former Soviet Union (FSU) in the years immediately following independence in 1991, the country experienced a major reversal in both economic and social development. The economic upheaval accompanying transition from a planned to a market-led economy, the disruption of traditional trading partnerships and the withdrawal of subsidies from Moscow following the break-up of the FSU resulted in a dramatic drop in GDP and central government expenditure. GDP fell by over 50% during the first 5 years of transition. Although there was a return to positive economic growth in the late 1990s, recovery has been slow and in 2005 GDP per capita was US$1927 PPP (purchasing power parity) (UNDP 2008). On the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) Human Development Index (a composite measure of life expectancy, adult literacy and educational attainment, and per capita GDP), at 0.696 Kyrgyzstan is now ranked 116th out of 177 countries worldwide (UNDP 2008). It is estimated that just under half of the population (46%) are living below the poverty line (NSC 2005).

Public spending on health care expenditure as a percentage of GDP dropped from over 6% in 1994 to around 2% in 2000 (UNICEF 2009), and it is estimated that per capita government expenditure on health in 2005 was just US$20 PPP (WHO 2008). The decline in government spending on health has been accompanied by an increase in private expenditure by households, both in terms of official charges and, more commonly, under-the-counter or informal payments. Informal payments have been defined as ‘payments to individual and institutional providers in-kind or cash that are outside the official payment channels, or are purchases that are meant to be covered by the health care system’ (Lewis 2002).

Evidence suggests that informal payments for health care were extensive throughout Central Asia in the late 1990s (Ladbury 1997; Ensor and Savelyeva 1998; Sari et al. 2002; Falkingham 2004). Although in principle medical supplies and drugs required as part of inpatient treatment remained free (or included in a one-off co-payment), the scarcity of such items in medical facilities led to an increasing number of patients having to purchase them. Furthermore, local budgetary constraints and petrol shortages eroded the capacity of the ambulance service, and often patients had to provide their own transportation to medical facilities. Most importantly, informal user charges for consultations were frequently being imposed to help subsidize salaries. Although there is a tradition in the region of presenting monetary or in-kind gifts to caregivers as a mark of gratitude, evidence suggests that this voluntary tradition was being supplemented or even supplanted by provider-generated demands for payment as a precondition of treatment (Sari et al. 2002). Informal payments tend to penalize poor households and can have a significant impact on access to health care services (Falkingham 2002).

Reform of health financing in Kyrgyzstan

The Kyrgyz government was amongst the first in the region to explicitly recognize the negative impact on equity of informal payments. Stemming the growth in out-of-pocket payments has provided a key stimulus for reform of the health financing system. A household survey revealed that, even as early as 1994, 69% of outpatients and 86% of inpatients in Kyrgyzstan contributed something towards the cost of their care in what were ostensibly free (except for some limited official user charges) government health facilities (Abel-Smith and Falkingham 1995). The growth of informal payments in Kyrgyzstan was confirmed by subsequent household surveys, and in 2001 virtually all patients were found to have paid something towards their hospitalization (Falkingham 2001). Qualitative research found that during their stay in hospital, patients had to contribute to the costs of their care both in terms of purchasing medicines, syringes and other supplies such as IV tubes and bandages, but also paid for light bulbs, linen and food (Schuth 2001).

In 1994, following the first survey on out-of-pocket payments, the Ministry of Health requested technical assistance from the World Health Organization (WHO) Regional office for Europe to develop a comprehensive health reform programme, and in 1996 the national MANAS Health Care Reform Programme (1996–2005) was adopted. Improving equity by guaranteeing patient’s rights and access to existing health services was highlighted as one of the four main policy goals of the programme (Meimanaliev et al. 2005). A chronology of reforms within the health sector in Kyrgyzstan is provided in Table 1. The main thrust and novelty of the Kyrgyz reforms has been the retention of the predominance of general tax financing whilst introducing a new institutional arrangement as the single purchaser of health care services for the whole population (Kutzin et al. 2009).

Table 1.

Chronology of events and legislation in the health sector

| Date | Event |

|---|---|

| August 1991 | Declaration of independence of Kyrgyzstan. |

| 1993 | Introduction of user fees. |

| March 1994 | Memorandum of Understanding between WHO Regional office for Europe and the Ministry of Health of the Kyrgyz Republic to undertake the MANAS Health Care Reform Programme. |

| Ministry of Health requests technical assistance from USAID for a health insurance demonstration project in Issyk-Kul oblast. | |

| August 1994 | National Health Policy approved by the government. |

| Nov 1996 | Government approves MANAS Health Care Reform Programme. |

| World Bank funded Health Project (1996–2000) started in Kyrgyzstan (Bishkek and Chui oblasts). | |

| Jan 1997 | Introduction of the mandatory health insurance system in Kyrgyzstan. |

| July 1997 | MHIF introduces case-based payment to hospitals. |

| 1977–1998 | Rolling out of primary health care reforms to Chui, Jalal-Abad and Osh oblasts and Bishkek. |

| June 1998 | Introduction of partial fundholding in 14 Family Group Practices (FGPs) in Karakol city, Issyk-Kul oblast. |

| Nov 1998–March 1999 | FGPs enrolment campaign in Chui oblast and Bishkek. |

| Jan 1999 | Introduction of capitation payment to FGPs in Bishkek. |

| April 1999 | About 55 hospitals and 290 FGPs enter into contracts with the MHIF. |

| Jan 2001 | Government decree on Introduction of a New Health care Financing Mechanism in Health facilities of Kyrgyzstan since 2001. |

| Government decree on Programme of State Guarantees on Provision of Free and Exempt Health Care to Citizens of Issyk-Kul and Chui oblasts in 2001. | |

| Government decree on Population’s Co-Payment for Drugs, Meals and Certain Types of Health Services Rendered by Health Facilities besides the Programme of State Guarantees on Provision of Free and Exempt Health Care to Citizens of Issyk-Kul and Chui oblasts in 2001. | |

| Feb 2002 | Government decree on Provision of Health Care to Citizens of Kyrgystan under the State Benefits Package since 2002. |

| March 2002 | Naryn and Talas oblasts join the single payer system. |

| March 2003 | Batken, Jalal-Abad and Osh oblasts join the single payer system. |

| Nov 2003 | Republican facilities join the single payer system. |

| July 2004 | Law on the Single Payer System in Health Care Financing in the Kyrgyz Republic. |

| March 2005 | Popular uprising and subsequently new government elected. |

| Feb 2006 | Government approves ‘Manas Taalimi’ Health Care Reform Programme 2006–2010. |

Source: adapted from Meimanaliev et al. (2005).

The Mandatory Health Insurance Fund (MHIF), established in 1997, introduced a new system of provider payment methods that were aimed at increasing efficiency and responsiveness to population and patient needs. These included case-based payment for inpatient care and capitation payment for primary care (Kutzin et al. 2002). Since then, the country has gradually moved from subsidizing the supply of services to subsidizing the purchase of services through the health insurance fund. In 2001, a series of related changes were introduced under the rubric of the ‘Single Payer’ reform. The reforms were implemented on a phased basis, being introduced first in the pilot oblasts (administrative regions) of Chui and Issyk-Kul (2001), then extended to Naryn and Talas (2000), Jaladabad and Batken (2003) and finally to Osh (late 2003/early 2004) and the capital Bishkek (2004). The ‘Single Payer’ reform involved a radical change in pooling arrangements for budget funds, complemented by a unification of provider payment methods from budget and MHIF revenues and measures to increase transparency of financial contributions by patients.

The Single Payer reform consolidated the split between purchasers and providers, with the MHIF becoming the single purchaser. In addition the reform introduced a State Guarantee Benefit Package (SGBP) with free primary health care from a contracted Family General Practitioner (FGP)/Family Medicine Centre (FMC), with whom the insured person is enrolled, and a formal co-payment for hospital inpatient care on referral. The SGBP includes the list of people who are eligible for free or nearly free provision of health care, i.e. exempt categories of the population based on individual or disease-specific characteristics, such as Second World War veterans, low-income pensioners, cancer, TB, etc. In addition, SGBP includes the co-payment rates that should be contributed by patients for inpatient care and outpatient specialist services based on their entitlements, and it also provides access to the Additional Drug Package (ADP) for the outpatient (HPAU 2007).

By increasing the transparency of the co-payment system and by improving the flow of resources to health care providers, it was hoped that the health financing reforms would reduce or even eliminate informal payments, particularly in hospitals. As mentioned above, one of the key reasons for the growth of informal payments, in addition to the need to purchase supplies, was the demand for payments by health workers in order to subsidize their salaries. According to official government statistics, wages in the health sector have always been below average for the country and had declined in relative terms from 92% of the average wage in 1994 to just 51% by 2001 (NSC 2003). By allowing the co-payment made by households to stay at the level of the facility and by introducing a clear system of payments by the MHIF to providers, it was anticipated that funding would be improved and so the need to subsidize wages would be reduced.

This article examines recent trends in health care use and out-of-pocket payments for health care over the period 2001–2007; the same period of time that extensive health reforms were taking place in Kyrgyzstan, including the Single Payer reform. It is important to bear in mind that other changes in the economy during this period may also impact upon both the demand for medical care and the ability of households to pay for care. For example, between 2001 and 2007, real GDP per capita increased by 19% (UNICEF 2009). However, although it is not possible to establish causality between the reforms and trends in household spending on health care, the trends nevertheless are instructive in helping to assess the extent to which the Single Payer reform has achieved its aims of replacing unofficial out-of-pocket payments with a transparent official co-payment and reducing the financial burden of health care spending for the poor.

Methods

This article analyses the health module of the Kyrgyz Integrated Household Survey (KIHS) conducted in March 2007 on behalf of the Ministry of Health. Where appropriate, the results from the 2007 KIHS are compared with those from the 2004 and 2001 KIHSs, which had the same design (Falkingham 2001; Baschieri and Falkingham 2006). All three surveys were conducted with financial assistance from the UK Department for International Development (DFID) and were executed by the Kyrgyz National Statistical Committee (NSC) with international technical assistance by the author.

The 2007 survey instrument was composed of five main sections covering:

general demographic information about the household and its members;

utilization of health care services in the last 30 days and expenditure associated with such health care;

hospitalization in the last year;

knowledge of the household head regarding people’s rights under the SGBP developed by the MHIF;

self-reported health status of each household member over 18 years old and whether they were covered by the MHIF. In addition, the questionnaire includes questions related to the risk factors of cardiovascular diseases, such as hypertension, overweight, smoking habits.

The questionnaire was administered to 5005 households nationwide producing a sample of 21 257 individuals. The KHIS sample design provides nationally representative data and weights are provided to ensure the sample is representative at the oblast level. The advantage of including the health financing module within the regular KHIS is that it is possible to link the health and health service utilization data to detailed information on household income and expenditure over the preceding year, allowing the calculation of the burden of health care expenditure on households.

As the survey was conducted as part of the on-going KHIS, where enumerators visit the same households on a monthly basis to collect basic information on expenditure, it is unlikely that the questions on payments for health care would be affected by ‘courtesy bias’ that might affect similar surveys conducted either within a health facility or as part of an exit interview. Other non-sampling errors such as non-response and recall error are also thought to be low.

Measuring out-of-pocket payments

There are four types of out-of-pocket payments for health care:

informal under-the-counter payments in cash or kind for services and goods in public health facilities that are meant to be provided without payment;

purchase of goods and services from private suppliers, mainly outpatient drugs from private pharmacies and bazaars, but also private health care;

official user fees and official co-payments by patients to health facilities included in the single payer system;

gifts (which are not solicited and which may be in addition to informal payments).

Distinguishing between formal and informal payments for health services is complex (Lewis 2002). Although specific questions were included in the KIHS on both official charges for consultations with health professionals and the value of unofficial ‘gifts’ (including money, food, jewellery, services, etc.) made to medical staff for a consultation, it is likely that some respondents could have been unclear whether ‘charges’ demanded by medical personnel prior to consultation were ‘official’ (i.e. legally sanctioned) or not. Thus it is difficult to isolate formal co-payments from additional informal payments.

The status of out-of-pocket payments for drugs and medical supplies is also ambiguous as such payments are only defined as being informal payments if the government is meant to cover the costs but fails to do so. The survey distinguishes between payments for drugs covered under a prescription and other drugs, but does not ask whether the respondent expected the drugs to be provided free but had to pay for them. Thus it is impossible to disentangle informal payments, formal payments and private payments for pharmaceuticals. Similarly, the in-kind provision of food, linen and personal care by relatives during an inpatient stay in hospital may simply be seen as an optional luxury for those who do not want to rely on standard care. However, if these services are provided out of necessity by relatives due to the hospital’s failure to provide them, then such services become informal payments in kind. Again the survey does not allow us to disentangle the motivation for relatives providing in-kind services.

Finally, there is a tradition in Central Asia of presenting monetary or in-kind gifts to caregivers as a mark of respect and appreciation. During the soviet era it was common practice to give medical personnel gifts of chocolates or flowers. The questionnaire survey does attempt to differentiate between gifts that were freely given and those that were coerced, asking a series of questions on whether the gift was given before or after the consultation (if given before, this may imply that the patient is seeking to obtain some assurances about the quality of the treatment to be provided rather than thanks for a treatment received) and whether the gift was requested outright, hinted at or freely given (see Box 1). As is good practice in all questionnaire design, there is also the inclusion of a category that allows the respondent not to answer. ‘Difficult to say’ is the equivalent of the traditional ‘don’t know’ category and provides respondents with a way to decline to answer as it is unlikely that they would not remember.

Box 1 Questions regarding gifts to medical personnel from the questionnaire of the Kyrgyz Integrated Household Survey 2007.

13. Did [NAME] make any gifts (money, food, jewellery, etc.) or provide any services to this person, besides the payment? If yes, what was the value of the gift or services?

14. Was the gift given before, during or after the consultation?

Before… 1

During… 2

After… 3

Difficult to say… 4

15. Did [NAME] give it as a gift or was it requested by the person?

It was a gift… 1

The person asked for it… 2

The person hinted for it … 3

Difficult to say… 4

Given the difficulties in isolating informal payments from official charges and gifts, the main analysis presented below focuses not on informal payments per se, but on all out-of-pocket payments incurred by individuals as a result of using health care services. However, where possible, distinctions between the different types of payments are made.

Results

Utilization of health care services

Table 2 presents some summary statistics on the use of health services in the Kyrgyz Republic. Overall 9.6% of the population sought medical assistance in the 30 days prior to the survey in March 2007 and 6.8% had been hospitalized in the previous year. Health care utilization varies by age (with use being highest amongst the young and the old) and by gender (with more women consulting than men). There are clear regional differentials, and utilization of primary care also varies by socio-economic group, with those in the richest 20% of the population (as defined by quintile group of per capita household expenditure) being more likely to seek medical assistance than other groups. This pattern has also been found elsewhere in the region (Falkingham 2004), and one possible explanation for this is that people from the lower end of the welfare distribution may be being deterred from seeking health care due to its cost.

Table 2.

Health care use in the Kyrgyz Republic, 2007

| % who sought medical assistance in last 30 days | % hospitalized in last year | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| 0–17 | 7.9 | 2.8 |

| 18–64 | 9.7 | 8.8 |

| 65+ | 19.3 | 12.6 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 6.7 | 4.3 |

| Female | 12.3 | 9.0 |

| Type of residence | ||

| Urban | 11.5 | 6.3 |

| Rural | 8.5 | 7.1 |

| Place of residence | ||

| Issyk-Kul | 11.7 | 8.5 |

| Jala-Abad | 8.7 | 3.5 |

| Naryn | 13.0 | 12.7 |

| Batken | 8.5 | 7.1 |

| Osh | 8.9 | 6.6 |

| Talas | 6.9 | 3.7 |

| Chui | 9.7 | 8.3 |

| Bishkek | 10.9 | 7.2 |

| Quintile | ||

| Bottom 20% | 7.6 | 5.6 |

| Quintile 2 | 7.3 | 5.0 |

| Quintile 3 | 11.6 | 5.3 |

| Quintile 4 | 11.0 | 7.0 |

| Top 20% | 12.1 | 9.4 |

| ALL | 9.6 | 6.8 |

Source: authors' own analysis 2007 KIHS.

The advantage of a household survey rather than a facility-based survey is that a household survey captures both users and non-users of health care. In addition to the 7% of Kyrgyz men and 12% of Kyrgyz women who reported in March 2007 that they had sought medical assistance in the previous 30 days, a further 13% of men and 21% of women reported that they had needed medical assistance but had not sought treatment. This is an increase on the proportions found in previous surveys in 2001 and 2004. However, the main reason given for not seeking health care in 2007 was that the person self-medicated using either pharmaceuticals (82%) or herbs (9%). Three per cent of men and 2% of women thought that the problem would go away. Only 4% of both men and women reported that they did not seek medical assistance because it was ‘too expensive’.

In order to assess the success of the reforms in the health sector, the ‘Manas Taalimi’ (national health reform programme for 2006–2010) includes a number of ‘dashboard indicators’ in a series of different domains. The first indicator for improving ‘accessibility and equity of health services’ is ‘the share of population that did not seek necessary health care due to lack of money and remoteness of health care facility’. According to analysis of the 2001–2007 KIHS, the proportion of the population that cited ‘expense’ or ‘distance to facility’ as the main reason for not seeking care when they needed it has decreased significantly, from 14.7% in 2001 to 5.7% in 2004 and to 3.6% in 2007. Thus, on this indicator, it is clear that the recent health reforms have made considerable progress in reducing financial barriers to accessing health care in Kyrgyzstan. Below we examine payments for health care in more detail to see if the reforms have been successful in reducing or even eradicating informal payments.

Paying for health care: the extent of out-of-pocket payments

Primary care

Under the Single Payer reform, primary health care from a FGP where a person is enrolled should be free. Previous research analysing the results from the 2004 KIHS reported that the proportion paying for primary health care increased between 2001 and 2004, despite the introduction of the reforms (Baschieri and Falkingham 2006). Analysis of the 2007 survey reveals the good news that the proportion of people who visited an FGP where they were enrolled who reporting making any payment has fallen from 17% in 2004 to 13% in 2007, and the share of those paying at a polyclinic/FMC has fallen from 45% in 2004 to 23% in 2007 (Table 3). Furthermore, no-one in the 2007 survey reported making a payment for maternity care, highlighting the success of the reforms in improving access to antenatal care. The proportion paying also varied by the type of personnel consulted, with those reporting paying to see a state doctor falling from 21% to 13%, whilst those paying a private doctor increased from 45% in 2004 to 67% in 2007.

Table 3.

Percentage reporting paying for a consultation and average payments made, by type of medical personnel providing care and facility visited, 2001, 2004 and 2007

| % reporting paying for consultation | Mean amount paid (soms) | Median amount paid (soms) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 | 2004 | 2007 | 2004 | 2007 | 2004 | 2007 | |

| Type of medical personnel consulted | |||||||

| Private doctor | 46 | 45 | 67 | 132 | 441 | 60 | 100 |

| State doctor | 17 | 21 | 13 | 93 | 130 | 30 | 50 |

| Nurse | 19 | 12 | 8 | 129 | 82 | 35 | 100 |

| Feldsher | 33 | 32 | 27 | 130 | 85 | 200 | 60 |

| Midwife | 3 | 22 | 1 | 38 | 33 | 20 | 25 |

| Pharmacist | – | – | 1 | – | 60 | – | 60 |

| Dentist | 63 | 84 | 84 | 203 | 382 | 50 | 125 |

| Healer | 60 | 37 | 41 | 114 | 97 | 100 | 50 |

| Other | – | – | 4 | – | 50 | – | 50 |

| Total | 22 | 27 | 20 | 118 | 234 | 40 | 60 |

| Type of facility visited | |||||||

| Patient’s home | 19 | 19 | 8 | 117 | 102 | 30 | 100 |

| FGP (enrolled) | 10 | 17 | 13 | 44 | 86 | 25 | 50 |

| FGP (not enrolled) | 42 | 41 | – | 210 | – | 50 | – |

| Polyclinic (without FGP)/FMC | 28 | 45 | 23 | 105 | 131 | 40 | 50 |

| SVA | 19 | 30 | – | 37 | – | 30 | – |

| FAP | 18 | 21 | 6 | 42 | 121 | 20 | 50 |

| Hospital | 32 | 31 | – | 179 | – | 50 | – |

| Private office | 73 | 79 | 72 | 325 | 482 | 60 | 150 |

| Maternity home | 12 | 14 | – | 199 | – | 300 | – |

| Other | 49 | 36 | 19 | 187 | 244 | 100 | 200 |

| Specialist in FMC | n.a. | 58 | – | 60 | – | 60 | – |

| Specialist in private office | n.a. | 76 | – | 62 | – | 25 | – |

| Total | 22 | 27 | 20 | 118 | 234 | 40 | 60 |

Note: ANOVA for between group variation significant at P < 0.001.

A range of patients are exempt from making a co-payment, either on the basis of suffering from a particular chronic illness (e.g. diabetes, TB, asthma) or on the basis of being in a particular category (children under 1 year, Second World War hero, registered disabled). The survey also provides some useful insights into the functioning of the system of exemptions. In 2007, 27% of those who fell into one of the ‘exempt’ categories sought medical assistance; and these ‘exempt’ categories constituted 8% of all consultations. Only 9% of exempt people reported making a payment for a consultation compared with 21% of non-exempt people. This is a significant improvement on the 15% of ‘exempt’ patients making a payment in 2004, indicating that the system of exemptions is operating more effectively.

Once the co-payment has been made, in theory there should be no other charges in relation to the consultation. In 2007, a similar level of people reported that they made ‘other payments’ in connection with the consultation, such as those for diagnostic tests, as was the case in 2004 (20% vs. 17%, respectively). This is a marked reduction in comparison with 32% in 2001 and 55% in 1994. Moreover, fewer than 2% reported presenting a gift to health personnel during the consultation. In this respect, it appears that the new charging mechanism of a single co-payment is working well.

Table 4 shows the total amount of money paid in relation to a consultation, including travel, gifts and prescriptions. In 2007, the mean amount paid in relation to a consultation, amongst all who consulted a health professional, was 355 soms. In the first quarter of 2007 the exchange rate was US$1 to 40 soms, so this is equivalent to US$8.90. Over half of all people paid nothing at all for any service, including transport to the consultation, with the result that the median payment was zero. Spending on prescriptions constitutes the largest share of total expenditure (64%), followed by payments for consultations (11%). The mean amount paid for a consultation was 38 soms, equivalent to around 3% of total monthly wages earned by a health care professional.

Table 4.

Average amounts paid in relation to consultation with a health professional, amongst all who consulted, 2001, 2004 and 2007

| Travel expenses | Consultation | Gift for consultation | Other payments | Other gifts | Prescriptions | Total expenditure | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 | |||||||

| Median (soms) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 25 | 50 |

| Mean (soms) | 13 | 24 | 7 | 9 | 1 | 94 | 148 |

| Item share of total expenditure (%) | 9 | 16 | 5 | 6 | <1 | 64 | 100 |

| 2004 | |||||||

| Median (soms) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 70 | 0 |

| Mean (soms) | 13 | 31 | 4 | 13 | 1 | 183 | 245 |

| Item share of total expenditure (%) | 5 | 13 | 2 | 5 | <1 | 75 | 100 |

| 2007 | |||||||

| Median (soms) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 70 | 0 |

| Mean (soms) | 26 | 38 | 3 | 23 | 2 | 228 | 355 |

| Item share of total expenditure (%) | 7 | 11 | 1 | 7 | <1 | 64 | 100 |

Source: authors' own analysis KIHS.

Looking at the burden of health care expenditure, amongst those who have consulted in the last month, spending on outpatient care accounts for 34% of per capita household expenditure amongst those from the poorest quintile compared with just 16% amongst the richest (and 24% for all households). Thus in poor households, the ill health of one person can account for around one-third of usual per capita consumption. Although overall financial access for outpatient treatment has improved, the burden of health care payments for the poor is still significant.

Hospital care

As seen in Table 2, in the 12 months prior to the 2004 survey 6.4% of all respondents reported at least one hospital inpatient stay. Of these, 7% were hospitalized twice and 4% three or more times. The majority of people attended a hospital close to their home, with the median distance travelled being just 8 km. However, there was a very wide degree of variation, with a minimum of 100 metres and maximum of 1100 km.

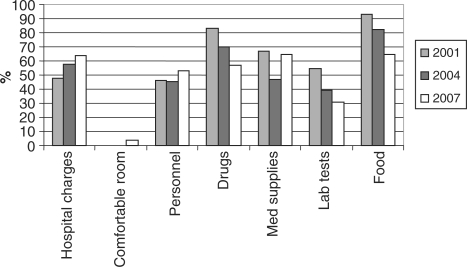

Hospitalization represents a major expenditure for most households. As Figure 1 shows, although the proportion paying hospital charges has increased between 2001 and 2007, the proportion reporting making payments for drugs, laboratory tests and food has fallen, which suggests the single co-payment policy is taking effect. Although this is excellent news, it is important to note that there has been no fall in the proportion reporting making payments to medical personnel. Moreover, the proportion paying for medicines and other services during hospitalization still remains high. In 2007, amongst all inpatients, 65% reported paying for food, 65% for medicines, 64% for hospital charges and 31% for laboratory tests. Four per cent of hospital inpatients reported paying an additional official charge for a comfortable room. Over half of people paying hospital and laboratory charges reported that they did not get a receipt, making it difficult to identify whether these charges were formal or informal.

Figure 1.

Proportion paying for services during hospitalization, 2001–2007.

There is evidence that in 2007 a slightly lower proportion of the poor paid hospital charges and for other services than the rich (Table 5). Moreover, those in the lowest quintile paid, on average, a lower amount. However, even then costs of charges and medicines could be prohibitive. The median payment for medicines for those in the lowest quintile was 500 soms, which is in addition to the official co-payment of 500 soms.

Table 5.

Proportion paying for services during hospitalization, with mean (median) values amongst those who have paid, by economic status quintile (%) 2007

| Poorest 20% |

Richest 20% |

All Kyrgyzstan |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % paying | Mean (median) | % paying | Mean (median) | % paying | Mean (median) | |

| Hospital charges | 66 | 491 (500) | 70 | 1076 (750) | 67 | 751 (530) |

| Food | 82 | 552 (400) | 98 | 785 (600) | 93 | 644 (500) |

| Medicines | 59 | 568 (450) | 59 | 1063 (500) | 57 | 988 (500) |

| Other supplies | 65 | 114 (100) | 68 | 125 (60) | 67 | 121 (60) |

| Laboratory tests | 23 | 126 (100) | 31 | 197 (120) | 31 | 135 (90) |

| Comfortable room | 0 | 10 | 700 (700) | 4 | 728 (700) | |

Source: authors' own analysis KIHS.

Table 6 presents information on the proportion making a payment/gift direct to staff during hospitalization. The differences by economic status partly reflect differences in the types of treatment obtained during hospitalization. In general, a low proportion of inpatients report making direct payments to staff. However, when they do so, the size of the payments may be considerable—especially to surgeons, where the median payment is 1000 soms. There appears to be some evidence that payments are solicited by hospital staff, particularly anaesthesiologists, although in the majority of cases inpatients reported that the payment was a gift (Table 7).

Table 6.

Proportion of inpatients making a payment/gift to staff during hospitalization, with mean (median) values amongst those who have paid, by economic status quintile (%), 2007

| Poorest 20% |

Richest 20% |

All Kyrgyzstan |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % paying | Mean (median) | % paying | Mean (median) | % paying | Mean (median) | |

| Physician services | 20 | 8 | 13 | |||

| Cash | 293 (200) | 427 (500) | 352 (300) | |||

| In-kind | 118 (100) | 225 (200) | 175 (150) | |||

| Surgeon | 10 | 18 | 14 | |||

| Cash | 1185 (300) | 5527 (1000) | 3372 (1000) | |||

| In-kind | 528 (500) | 392 (350) | 475 (350) | |||

| Paediatrician | 2 | 7 | 5 | |||

| Cash | 128 (100) | 374 (500) | 262 (150) | |||

| In-kind | 102 (100) | 120 (120) | 119 (100) | |||

| Gynaecologist | 18 | 22 | 18 | |||

| Cash | 191 (200) | 1072 (500) | 586 (200) | |||

| In-kind | 129 (100) | 174 (150) | 196 (150) | |||

| Anaesthesiologist | 2 | 9 | 5 | |||

| Cash | 197 (200) | 454 (300) | 489 (300) | |||

| In-kind | – | 108 (100) | 176 (200) | |||

| Ancillary staff | 6 | 10 | 8 | |||

| Cash | 99 (100) | 159 (100) | 196 (100) | |||

| In-kind | 68 (50) | 97 (120) | 95 (100) | |||

| Other payments | 11 | 11 | 17 | |||

| Cash | 1544 (500) | 1288 (200) | 702 (200) | |||

| In-kind | 211 (100) | 237 (200) | 236 (200) | |||

Source: authors' own analysis KIHS.

Table 7.

Amongst those inpatients who paid, reasons why payments in cash or kind to selected health care staff were made, 2007 (%)

| It was a gift | Person asked for it | Person hinted for it | Difficult to say | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physician services | 65 | 5 | 17 | 13 | 100 |

| Surgeon | 55 | 22 | 13 | 11 | 100 |

| Paediatrician | 84 | 13 | 2 | 1 | 100 |

| Gynaecologist | 63 | 12 | 15 | 9 | 100 |

| Anaesthesiologist | 44 | 47 | 2 | 7 | 100 |

| Ancillary staff | 67 | 19 | 9 | 5 | 100 |

Source: authors' own analysis KIHS.

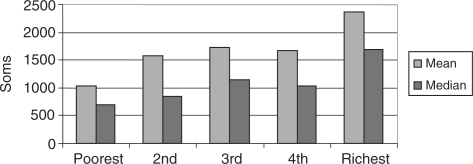

Overall, the mean total cost incurred during a spell in hospital in the year prior to the survey was 2452 soms (median 1650 soms). Of this, the co-payment accounted for 19%, drugs 25%, payments to personnel 25% and food 25%. Total expenditure on hospitalization, excluding food, also varied by economic status from a mean (median) of 1035 (700) soms for those living in the poorest fifth of households to 2373 (1700) for those living in the richest fifth of households (Figure 2). Thus, looking at absolute levels of payment, hospital payments appear to be progressive.

Figure 2.

Total expenditure on hospitalization (excluding food) by economic status, 2007.

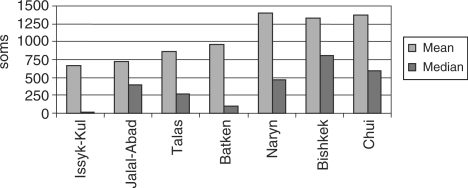

Given that one of the main purposes of the survey was to provide data for the evaluation of the new co-payments for inpatient stays, it is useful to examine the distribution of payments in relation to the co-payment thresholds. Using the current co-payment rates combined with information on patient status, i.e. exempt, insured, uninsured, without referral and whether or not the admission involved surgery, it is possible to calculate the actual payment over and above the expected co-payment. One way to assess the progress of the reform is to look at how the excess payment varies by region (Figure 3 and Table 8); as implementation of the reform was phased, we might expect those regions where the reform was implemented first to show a lower level of excess payment than those regions where the reform was implemented last. Secondly, we can assess equity by looking at the distribution of payment in excess of the co-payment by socio-economic group (Table 9).

Figure 3.

Payments for hospitalization in excess of co-payment rate, 2007.

Table 8.

Average payments in excess of co-payment rates by region, 2007 (soms)

| Expenditure incl. food |

Expenditure excl. food |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Median | Max | Mean | Median | Max | |

| Issyk-Kul | 1119 | 200 | 13 423 | 846 | 0 | 12 423 |

| Jalal-Abad | 642 | 160 | 6161 | 515 | 0 | 5761 |

| Talas | 1224 | 880 | 9711 | 968 | 580 | 8711 |

| Batken | 695 | 0 | 8561 | 389 | 0 | 8061 |

| Naryn | 989 | 130 | 8861 | 654 | 0 | 7861 |

| Bishkek | 1936 | 1230 | 13 350 | 1346 | 600 | 11 850 |

| Chui | 3287 | 202 | 20 200 | 2473 | 1120 | 17 210 |

| All Kyrgyzstan | 1688 | 890 | 20 200 | 1185 | 290 | 17 210 |

Source: authors' own analysis KIHS.

Note: The appropriate co-payment rates were calculated taking into account whether the co-payment was for admission with diagnosis and treatment only, or for admission with surgery and taking into account the patient’s status, i.e. exempt, insured, uninsured or without referral.

Table 9.

Average payments in excess of co-payment rates by socio-economic group (soms)

| Expenditure incl. food |

Expenditure excl. food |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Median | Max | Mean | Median | Max | |

| Poorest 20% | 891 | 462 | 13 423 | 531 | 30 | 12 423 |

| Quintile 2 | 1169 | 340 | 13 350 | 835 | 0 | 11 850 |

| Quintile 3 | 1520 | 710 | 8862 | 1014 | 170 | 7861 |

| Quintile 4 | 1462 | 910 | 9911 | 1008 | 470 | 8011 |

| Richest 20% | 2404 | 1600 | 9973 | 1670 | 1000 | 9420 |

Source: authors' own analysis KIHS.

There are several points to note. First, substantial expenses over and above the co-payment rate are being incurred for hospital stays, particularly in Bishkek and Chui. However, median levels of payment are much lower than mean payments, indicating that a considerable proportion of patients are paying nothing or very little over and above the co-payment rates, but a few people are paying substantial amounts (see third column in Table 8). Secondly, if one excludes spending on food, then hospital expenditures are much lower and indeed median excess payments are zero everywhere except Talas, Bishkek and Chui—indicating that at least half of all inpatients do not pay more than the co-payment rate. Thus there is some evidence that the system of co-payments is impacting upon out-of-pocket payments related to hospitalization. However, there are still some poor people making significant payments (Table 9).

Discussion

On balance, analysis of the KIHS health module data over the period 2001–2007 shows encouraging signs that access to health care and equity within the health sector in the Kyrgyz Republic has improved. With regard to primary care, financial barriers to access are decreasing. The percentage of patients who report making a payment to a state provider fell between 2004 and 2007 and financial access to maternity care increased. The operation of the system of exemptions has improved and very few people report making gifts—indicating a decline in these types of informal payment. However, although overall financial access for outpatient treatment has improved, the burden of health care payments for the poor is still significant.

With regard to hospitalization, in the 12 months prior to March 2007, those in the richest households are 50% more likely to have had an inpatient stay than those in the poorest households (Table 2), indicating that barriers to access still remain. The good news is that fewer inpatients report making payments to medical personnel, but when payments are made they are high, especially to surgeons and anaesthetists. The overall out-of-pocket costs of inpatient care have fallen slightly and equity has improved. More than half of all inpatients are not making payment in excess of the co-payment rate; however, there are still some poor people making significant payments.

The Manas Taalimi sets out the reform agenda for 2006–2010 (Ministry of Health 2006). This ‘next generation’ of reforms aims to increase the effectiveness of primary health care, with a particular emphasis on building the capacity of feldsher-obstetrical points (FAPs) and ambulance services, and to increase funding for health care through improved revenue collection and improved purchasing of services with the guaranteed basic package. The Manas Taalimi explicitly lays out the goal of enhancing transparency in the allocation and use of funds within the health sector through the development of clear regulatory mechanisms for budget allocations.

Although other countries within the Central Asian region have implemented reform of their health care systems, it is arguable that outside of the Kyrgyz Republic there has been little significant progress in increasing the efficiency or effectiveness of the health sector, and that informal payments remain pervasive (Bonilla-Chacin et al. 2005). What lessons therefore are there from the Kyrgyz experience for the region more generally? One important characteristic of the Kyrgyz reforms is that they have been implemented over an extended period and have taken an incremental approach, piloting the changes in one locality before gradually implementing them nationally. Thus the first demonstration project of health insurance started in Issyk-Kul oblast in 1994; the Single Payer reform (which ended up with a different structure to the original pilot) was only fully implemented a decade later in 2003. Data have been used to evaluate the reforms and modify the reform design. The availability of time series data on both financial flows and patient episodes from the MHIF, along with household level data from the KIHS, has provided a rich evidence base with which to inform policy. The presence of the WHO Health Policy Analysis Project within the Ministry of Health building has further strengthened the analytical base, along with extensive capacity building within both the Ministry of Health and MHIF (Kutzin et al. 2009).

A further important factor in the successful implementation of the reform process has been the usually high level of co-ordination and co-operation between the government and all the key international and bilateral donors working in the health sector in Kyrgyzstan. Early on in the process, the MANAS Programme became the umbrella project for all the various actors and this has meant that all the activities have focused on achieving the same set of goals. The MANAS Programme contributed to the Poverty Reduction Strategy, and the Monitoring Indicator Package for the Manas Taalimi includes indicators that are also part of the Comprehensive Development Framework (the successor to the Poverty Reduction Strategy). This joined-up thinking has helped ensure that improving access to health services remains at the centre of policy development.

The Kyrgyz health sector has been at the forefront of reforms within the region and it is hoped that this emphasis on the achievement of equity and accessibility of health services for the entire population continues. It is clear from the analysis presented here that the Single Payer reform has succeeded in formalizing some informal payments but there is still scope for further progress. A further KIHS health module is planned for 2010 as part of the monitoring and evaluation framework for Manas Taalimi. Analysis of that survey will shed light on the extent of out-of-pocket payments over and above the official co-payment level, and thus how much more work needs to be done to drive out informal payments.

Funding

The surveys on which the analyses presented here are based were funded by the UK department of International Development (DfID) through a trust fund with the World Health orgranisation (WHO).

References

- Abel-Smith B, Falkingham J. Private Payments for Health Care in Kyrgyzstan. London: Overseas Development Administration, Health & Population Division, Central Asia; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Baschieri A, Falkingham J. Formalizing informal payments: the progress of health reform in Kyrgyzstan. Central Asian Survey. 2006;25:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Bonilla-Chacin M, Murrugarra E, Temourov M. Health care during transition and health systems reform: evidence from the poorest CIS countries. Social Policy and Administration. 2005;39:381–408. [Google Scholar]

- Ensor T, Savelyeva L. Informal payments for health care in the Former Soviet Union some evidence from Kazakhstan. Health Policy and Planning. 1998;13:41–9. doi: 10.1093/heapol/13.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falkingham J. London: London School of Economics and Political Science; 2001. Health, health seeking behaviour and out of pocket expenditures in Kyrgyzstan 2001. DFID-funded Kyrgyz Household Health Finance Survey: Final Report. [Google Scholar]

- Falkingham J. Poverty, affordability and access to health care. In: McKee M, Healey J, Falkingham J, editors. Health Care in Central Asia. Buckingham; Open University Press; 2002. pp. 42–56. [Google Scholar]

- Falkingham J. Poverty, out of pocket payments and access to health care: evidence from Tajikistan. Social Science & Medicine. 2004;58:247–58. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(03)00008-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HPAU. Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan: Health Policy Analysis Unit; 2007. Analysis of the Medium-Term Financial Sustainability of the State Guaranteed Benefits Package. Research paper no. 43. [Google Scholar]

- Kutzin J, Ibraimova A, Kadyrova N, et al. Washington, DC: World Bank, Human Development Network; 2002. Innovations in resource allocation, pooling and purchasing in the Kyrgyz health care system. Health, Nutrition and Population Discussion Paper. [Google Scholar]

- Kutzin J, Ibraimova A, Jakab M, O’Dougherty S. Bismarck meets Beveridge on the Silk Road: coordinating funding sources to create a universal health financing system in Kyrgyzstan. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2009;87:549–54. doi: 10.2471/BLT.07.049544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladbury S. Unpublished; 1997. Turkmenistan health project social assessment study. Report to World Bank/Government of Turkmenistan. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis M. Informal health payments in Central and Eastern Europe and the Former Soviet Union: issues, trends and policy implications. In: Mossialos EA, Dixon A, Figueras J, Kutzin J, editors. Funding Health Care: Options for Europe. Buckingham: Open University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Meimanaliev A-S, Ibraimova A, Elebesov B, Rechel B. Health Care Systems in Transition: Kyrgyzstan. Copenhagen: 2005. WHO Regional Office for Europe on behalf of the European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health, Kyrgyz Republic. National Health Care Reform Program “Manas Taalimi” on 2006–2010. Executive Brief (English version) Bishkek: Ministry of Health; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- National Statistical Committee of the Kyrgyz Republic (NSC) Kyrgyzstan in Figures. Bishkek: NSC; 2003. Online at: http://nsc.bishkek.su/English/Index.htm. [Google Scholar]

- National Statistical Committee of the Kyrgyz Republic (NSC) Women and Men in the Kyrgyz Republic. Bishkek: NSC; 2005. Online at: http://nsc.bishkek.su/English/Index.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Sari N, Langenbrunner J, Lewis M. Affording out-of-pocket payments for health services: evidence from Kazakhstan. EuroHealth. 2002;6((Special Issue Spring)):37–9. [Google Scholar]

- Schuth T. If We Were the Minister of Health: A Participatory Study in Naryn Oblast. Bishkek: Swiss Red Cross; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- UNDP. Human Development Report 2007/8. New York: UNDP; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF. TransMONEEE 2009 Database. New York: UNICEF; 2009. Online at: http://www.unicef.org/irc. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. World Health Statistics 2008. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. [Google Scholar]