Abstract

Mice that were intranasally vaccinated with live or dead Chlamydia muridarum with or without CpG-containing oligodeoxynucleotide 1862 elicited widely disparate levels of protective immunity to genital tract challenge. We found that the frequency of multifunctional T cells coexpressing IFN-γ and TNF-α with or without IL-2 induced by live C. muridarum most accurately correlated with the pattern of protection against C. muridarum genital tract infection, suggesting that IFN-γ+–producing CD4+ T cells that highly coexpress TNF-α may be the optimal effector cells for protective immunity. We also used an immunoproteomic approach to analyze MHC class II-bound peptides eluted from dendritic cells (DCs) that were pulsed with live or dead C. muridarum elementary bodies (EBs). We found that DCs pulsed with live EBs presented 45 MHC class II C. muridarum peptides mapping to 13 proteins. In contrast, DCs pulsed with dead EBs presented only six MHC class II C. muridarum peptides mapping to three proteins. Only two epitopes were shared in common between the live and dead EB-pulsed groups. This study provides insights into the role of Ag presentation and cytokine secretion patterns of CD4+ T effector cells that correlate with protective immunity elicited by live and dead C. muridarum. These insights should prove useful for improving vaccine design for Chlamydia trachomatis.

Chlamydia trachomatis is an intracellular pathogen responsible for >92 million sexually transmitted infections and 85 million ocular infections per year worldwide (1). Sexually transmitted C. trachomatis is a major cause of long-term disease sequelae in women such as infertility and ectopic pregnancy (2, 3). The “seek and treat” programs to prevent and control C. trachomatis sexually transmitted infections appear to be failing, as case rates and reinfection rates continue to rise (4), possibly due to early treatment interfering with the development of protective immune responses (5). Thus, new approaches, such as an effective vaccine, are needed if control of C. trachomatis is to be achieved.

Previous attempts to vaccinate against C. trachomatis and Chlamydia muridarum infection in both human and murine models using dead elementary bodies (EBs) provided only limited protection (6–9). However, mice immunized with live C. muridarum EBs are known to generate complete protection (8, 10). Our laboratory has focused investigation on the mechanism underlying the efficient induction of immunity provided by live C. muridarum in comparison with dead organisms and previously demonstrated that dendritic cells (DCs) exposed to live or dead C. muridarum develop into distinct phenotypes. In particular, DCs exposed to live C. muridarum became mature and stimulated Ag-specific CD4 T cells, whereas DCs exposed to dead C. muridarum were inhibited in acquiring a mature phenotype. Costimulation of DCs with dead EB and CpG-containing oligodeoxynucleotide (CpG-ODN) partially overcame dead EB inhibition of DC maturation (11). Our laboratory has also investigated the transcriptional responses of bone marrow-derived DCs following exposure to live and dead C. muridarum using GeneChip microarrays. The study revealed marked differences in CXC chemokine profiles in DCs exposed to live or dead organism (12). In aggregate, the data demonstrate that DCs exposed to live EBs are phenotypically and functionally distinct from DCs generated by exposure to dead EBs. We therefore hypothesized that differences in DC maturation phenotype may contribute to differences between immunogenicity of live versus dead EBs.

Immunity to C. muridarum infection is known to be largely cell-mediated and is therefore dependent on Chlamydia-derived peptides presented to CD4 T cells via MHC molecules on APCs (13, 14). Recently our laboratory used an immunoproteomic approach (15–17) to identify C. muridarum T cell Ags, which was based on isolating and sequencing of pathogen-derived peptides binding to MHC class II molecules presented on the surface of DCs after they were pulsed with live EBs. We identified 13 C. muridarum peptides derived from eight novel epitopes (18). These peptides were recognized by Ag-specific CD4 T cells in vitro and recombinant proteins containing the MHC binding peptides were able to induce partial protection via immunization against C. muridarum infection in vivo (19). To investigate additional mechanisms behind differences in protection between dead and live EBs at the level of Ag presentation, we hypothesized that the type of pathogen peptides presented by MHC molecules may differ when DCs are pulsed with dead and live EBs.

The immune correlates for protection against C. trachomatis infection are known to be IFN-γ–mediated Th1 immune responses (20–22). However, other infection model systems have shown that using IFN-γ as a single immune correlate may not be sufficient to screen for protective immunity. Interestingly, this has been also observed for C. muridarum following adoptive transfer of CD4+ T cell clones (23). Flow cytometry allows assessment of individual cytokines simultaneously on a single-cell basis. Recent reports describing various disease targets in different animal models have demonstrated a correlation between protection and high-quality T cells that coexpress multiple cytokines (24–26). One of the effector cytokines shown in these studies mediating control of intracellular infection is TNF-α. TNF-α in combination with IFN-γ can synergize to mediate killing of pathogens (27). IL-2 has no direct effector function but strongly enhances the expansion of effector T cells. Therefore, it is of interest to use a cytokine set of IFN-γ, TNF, and IL-2 to define immune correlates for Chlamydia protection to study the difference in immunity induced by live and dead EBs.

Materials and Methods

Chlamydia

C. muridarum mouse pneumonitis strain Nigg was grown in HeLa 229 cells in Eagle’s MEM (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% FCS. Elementary bodies were purified by discontinuous density gradient centrifugation as previously described (28). Purified EBs were aliquoted and stored at −80°C in sucrose-phosphate-glutamic acid buffer and thawed immediately before use. The infectivity and the number of inclusion-forming units (IFU) of purified EBs were determined by immunostaining using anti-EB mouse polyclonal Ab followed by biotinylated anti-mouse IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) and a diaminobenzidine substrate (Vector Laboratories) (29). Dead EBs were prepared either by heating to 56°C for 30 min or by exposure to ultraviolet light from a G15T8 ultraviolet lamp (D. William Fuller, Chicago, IL) at a distance of 5 cm for 45 min at room temperature as previously described (8). Viability was tested on HeLa 229 cells to ensure complete inactivation of the heat- or ultraviolet-treated EBs. The IFU for both live and dead EBs were calculated from the titers determined on original C. muridarum EB-purified stocks as described above.

Mice

Female C57BL/6 mice (5 to 6 wk old) were purchased from Charles River Canada and housed under pathogen-free conditions at the Animal Facility of the Jack Bell Research Center. All experiments were performed in strict accordance with University of British Columbia guidelines for animal care and use.

Immunization

Three groups of mice were immunized with 1) 1500 IFU live EBs in-tranasally once, 2) 5 × 106 IFU dead EBs plus 20 μg CpG-ODN 1826 (5′-TCCATGACGTTCCTGACGTT-3′, phosphorothioate modified; Integrated DNA Technologies) intranasally three times at 2-wk intervals, and 3) 5 × 106 IFU dead EBs intranasally three times at 2-wk intervals. A non-vaccinated group was included as a naive control.

Genital tract infection challenge and C. muridarum quantification

Five weeks after the live EB immunization and 1 wk after the last dead EB immunization, mice were injected s.c. with 2.5 mg medroxyprogesterone acetate (Depo-Provera; Pharmacia and Upjohn). One week after medroxyprogesterone acetate treatment, mice were challenged intravaginally with 1500 IFU C. muridarum. Cervicovaginal washes were taken at day 6 postinfection and were stored at −80°C for Chlamydia titration on HeLa cells as described previously (29).

Multiparameter flow cytometry

Six weeks after the live EB immunization and 2 wk after the last dead EB immunization or 1 wk after live EB challenge, mice from specified groups were sacrificed and cells harvested from spleen were stimulated with killed EBs (5 × 105 IFU/ml) in complete RPMI 1640 for 4 h at 37°C. Brefeldin A was added at a final concentration of 1 μg/ml, and cells were incubated for an additional 12 h before intracellular cytokine staining. Cells were surface stained for CD3, CD4, and CD8 as well as with the viability dye, red fluorescent reactive dye (L23102; Molecular Probes), followed by staining for IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-2 by using a BD Cytoperm Plus Fixation/Permeabilization (BD Pharmingen) kit. Finally, the cells were resuspended in a 4% formaldehyde solution. All Abs and all reagents for in-tracellular cytokine staining were purchased from BD Pharmingen except where noted. We collected 200,000 live splenocytes per sample by using a FACSAria flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) and analyzed the data by using FlowJo software (Tree Star).

DC pulsing with live or dead EBs

DCs were generated as previously described (30). Briefly, bone marrow cells were isolated from the femurs of C57BL/6 mice and cultured in Falcon petri dishes at 4 × 107 cells in 50 ml DC medium. DC medium was IMDM supplemented with 10% FCS, 0.5 mM 2-ME, 4 mM L-glutamine, 50 μg/ml gentamicin, and 5% of culture supernatant of murine GM-CSF–transfected plasmacytoma X63-Ag8 and 5% of culture supernatant of murine IL-4–transfected plasmacytoma X63-Ag8, which contained 10 ng/ml GM-CSF and 10 ng/ml IL-4, respectively. The above two cell lines were kindly provided by Dr. F. Melchers (Basilea Institute, Switzerland). At day 3, half of culture supernatants were removed and fresh DC medium was added. At day 5, nonadherent cells (purity of >50% CD11c+) were transferred to new dishes and cultured at 25 × 107 cells in 50 ml DC medium containing 25 × 107 IFU live EBs or dead EBs, respectively, at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 12 h. The cells pulsed with live EBs or dead EBs were then harvested and stored in −80°C.

Identification of MHC class II-bound peptides

We acquired 6 × 109 DCs pulsed with live EBs or dead EBs. The immunoproteomic approach to identify MHC class II-bound peptides from pulsed DCs involved multiple steps as previously described (18). Briefly, the pulsed DCs were lysed and MHC class II (I-Ab) molecules were purified using allele-specific anti-MHC mAb affinity columns. MHC class II molecules bound to the affinity column were then eluted and the MHC-bound peptides were separated from MHC molecules by acetic acid treatment and ultrafiltration through a 5-kDa cutoff membrane to remove high molecular mass material. The purified MHC-bound peptides were analyzed qualitatively using an LTQ Orbitrap XL (Thermo Scientific) online coupled to a nanoflow HPLC using a nanospray ionization source. The mass spectrometer was set to fragment the five most intense multiply charged ions per cycle. Fragment spectra were extracted using DTASuperCharge (http://msquant.sourceforge.net) and searched using the Mascot algorithm against a database comprised of the protein sequences from C. muridarum.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed with the aid of the GraphPad Prism software program. The Kruskal–Wallis test was performed to analyze data for C. muridarum sheddings from multiple groups, and the Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare medians between pairs. Comparison of cytokine productions and mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) as determined by multiparameter flow cytometry between two groups were analyzed using two-tailed t test. A p value <0.05 was considered significant. Data are presented as means ± SEM.

Results

Live and dead C. muridarum induce different levels of protection against C. muridarum genital tract infection

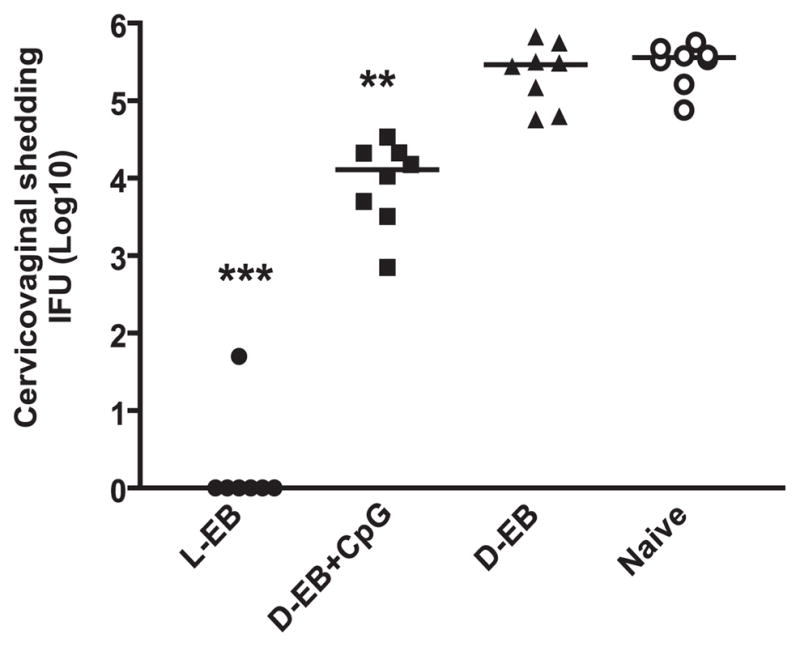

We compared live to dead EBs with or without CpG-ODN 1862 using intranasal routes of vaccination. Six weeks after live EB or 2 wk after final dead EB immunization, we compared Chlamydia inclusion titers in cervicovaginal washes at day 6 following genital tract challenge with live EBs to measure protection. As shown in Fig. 1, excellent protection was observed in mice given live EBs intranasally. Compared to the nonvaccinated group, mice intranasally vaccinated with dead EBs formulated with CpG exhibited a partial reduction in C. muridarum titers in the vaginal wash (p < 0.01). Vaccination with dead EBs alone did not reduce cervicovaginal shedding, demonstrating that vaccination with dead EBs alone failed to induce any measurable protective immunity against C. muridarum infection.

FIGURE 1.

Live and dead organisms induce different protection against C. muridarum genital tract infection. Mice were vaccinated with live EBs or dead EBs with or without CpG via intranasal route as described in Materials and Methods. Mice were intravaginally challenged with 1500 IFU live C. muridarum after immunization with a variety of vaccine formulations. Cervicovaginal washes were taken at day 6 after challenge, and bacterial titers were measured on HeLa 229 cells. *p < 0.01, **p < 0.001 in comparison with the corresponding nonimmunization (naive) group. D-EB, dead EBs; L-EB, live EBs.

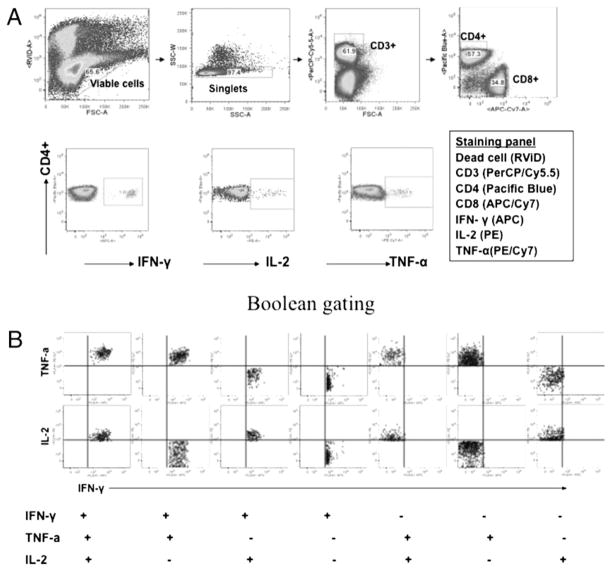

Functional characteristics of distinct populations of Th1 responses after live or dead EB immunization

To define a correlation between characteristics of Th1 responses and protection, we used multiparameter flow cytometry and assessed Ag-specific IFN-γ–, TNF-α–, and IL-2–producing CD4+ T cells in mice following immunization before and after C. muridarum challenge. As shown in Fig. 2, among mice in-tranasally immunized with live EBs, a seven-color flow cytometry panel was used to simultaneously analyze multiple cytokines at a single cell level. A typical gating tree hierarchically identifies functional populations of CD4+ T cells based on the fluorescence staining of live cells, CD3+ cells, and IFN-γ–, TNF-α–, and IL-2–producing CD4+ T cells (Fig. 2A). CD4+ cells that express each cytokine (IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-2) are entered into a Boolean gating analysis that separately identifies the seven populations that express each possible combination (Fig. 2B).

FIGURE 2.

Functional characterization of distinct populations of Th1 responses using multiparameter flow cytometry. A, The staining panel and gating strategy used to identify Ag-specific IFN-γ–, TNF-α–, and IL-2–producing CD4+ T cells in the splenocytes from a representative mouse with intranasal live EB immunization. B, Boolean combinations of the three total cytokine gates (IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-2) to uniquely discriminate responding cells based on their functionality or quality with respect to cytokine production.

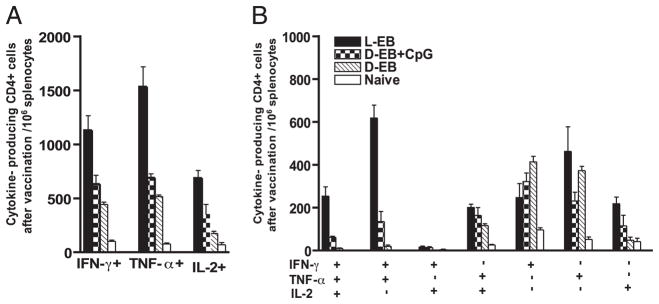

To assess the characteristics of the Th1 responses in vaccinated mice, the total Ag-specific CD4+ T cell cytokine responses comprising IFN-γ, TNF-α, or IL-2 from splenocytes were measured in each of the vaccine groups, 6 wk after live EB or 2 wk after final dead EB immunization. Overall live EB intranasal immunization showed the highest number of IFN-γ–, TNF-α–, and IL-2–secreting cells per 106 splenocytes (Fig. 3A). The number per 106 splenocytes of IFN-γ+TNF-α+ double-positive CD4 T cells was strikingly elevated in the live EB intranasally immunized group (Fig. 3B). The group immunized with dead EBs predominantly produced single-positive IFN-γ–producing CD4 T cells (Fig. 3B). The nonvaccinated group (naive mice) showed very low background cytokine levels, indicating that cytokine-producing cells detected in the experimental system are C. muridarum-specific. Collectively, the data show that the total number of IFN-γ–producing CD4+ T cells is not strictly predictive of vaccine-elicited protection. Rather, protective efficiency is better correlated with cytokine coexpression profile of the CD4+ T cells.

FIGURE 3.

Ag-specific CD4+ T cell cytokine responses after EB immunization. EB-specific cytokine productions from splenocytes of vaccinated mice before challenge were analyzed by multiparameter flow cytometry. A, The total number of IFN-γ–, TNF-α–, or IL-2–producing CD4 T cells in 106 splenocytes. B, The number of cells expressing each of the seven possible combinations of IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-2. Three or four mice were in each group. Shown are results representative of two experiments. D-EB, dead EBs; L-EB, live EBs.

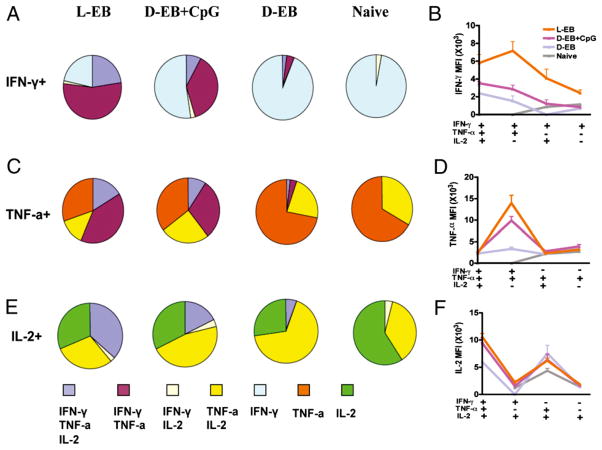

Each cytokine-producing cells in this analysis encompasses four distinct populations. For IFN-γ, it includes IFN-γ single-positive, IFN-γ+TNF-α+ double-positive, IFN-γ+IL-2+ double-positive, and IFN-γ+TNF-α+IL-2+ triple-positive CD4+ T cells. The relative percentage of the four distinct populations can help define the quality of the Th1 responses. Differences in the quality of IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-2 responses between vaccine groups is represented pictorially by pie charts (Fig. 4A, 4C, 4E). By quantifying the fraction of the total IFN-γ responses, we observed that the combination of IFN-γ+TNF-α+IL-2+ triple- and IFN-γ+TNF-α+ double-positive CD4+ T cells encompassed 77, 46, 6, and 0% of the total IFN-γ–producing cells in live EBs, dead EBs plus CpG, dead EBs alone, and naive groups, respectively (Fig. 4A). The MFI for IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-2 is an additional measure of cytokine production on a single cell basis (Fig. 4B, 4D, 4F). The MFI for IFN-γ of IFN-γ+TNF-α+IL-2+ triple- and IFN-γ+TNF-α+ double-positive CD4+ T cells from the live EB vaccine group was significantly higher than that from other vaccine groups (Fig. 4B). Analysis of TNF-α–producing CD4+ cells also showed a correlation between the number of multifunctional Th1 cells simultaneously secreting IFN-γ, as well as TNF-α and the degree of protection among the vaccine groups (Fig. 4C). Even more impressively, the MFI for TNF-α of IFN-γ+TNF-α+ double-positive CD4+ T cells correlated best with protection. The MFI for TNF-α of IFN-γ+TNF-α+ double-positive CD4+ T cells from the live EB vaccine groups is ~5-fold higher as compared with dead EB alone group (Fig. 4D). For IL-2–producing CD4+ cells, the fraction of IFN-γ+TNF-α+IL-2+ triple-positive CD4+ T cells was associated with protection (Fig. 4E). There was no difference in the correlation of MFI for IL-2 with protection (Fig. 4F).

FIGURE 4.

The IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-2 MFI and fraction of Ag-specific triple-, double-, and single-positive cells for each vaccine group. EB-specific cytokine productions from splenocytes of vaccinated mice before challenge were analyzed by multiparameter flow cytometry. The fraction of IFN-γ (A), TNF-α (C), and IL-2 (E) EB-specific triple-, double-, and single-positive cells for each vaccine group. The MFI of IFN-γ (B), TNF-α (D), and IL-2 (F) EB-specific triple-, double-, and single-positive cells for each vaccine group. Three or four mice were in each group. Shown are results representative of two experiments. D-EB, dead EBs; L-EB, live EBs.

IFN-γ+TNF-α+IL-2+ triple- and IFN-γ+TNF-α+ double-positive CD4+ cells correlate with protection against C. muridarum infection

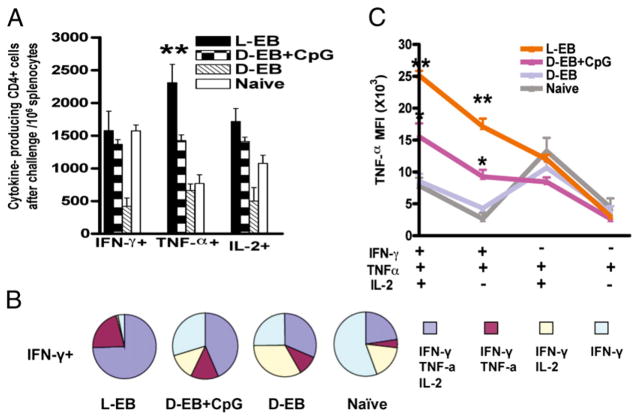

We next assessed the magnitude and quality of Th1 responses among the different vaccine-primed groups 7 d after the intra-vaginal C. muridarum challenge. There was little difference between the live EB and dead EB plus CpG vaccine groups in the three cytokine-producing CD4+ T cells apart from the higher total number of TNF-α–producing CD4+ T cells observed in the live EB group (Fig. 5A). Interestingly, nonvaccine-primed mice also developed similar numbers of IFN-γ–, TNF-α–, and IL-2–producing CD4+ T cells at day 7 after C. muridarum challenge when compared with mice that were vaccine primed with live EBs or dead EBs plus CpG. Vaccine priming with dead EBs alone induced significantly lower numbers of IFN-γ and IL-2 compared with the other vaccine groups (Fig. 5A). Of importance, >90% of IFN-γ–producing CD4+ T cells in the live EB vaccine group simultaneously expressed TNF-α with or without IL-2, whereas most IFN-γ–producing CD4+ T cells in the nonprotected groups (dead EBs alone and naive control) did not coexpress TNF-α (Fig. 5B). Moreover, the MFI for TNF-α of IFN-γ+TNF-α+IL-2+ triple-and IFN-γ+TNF-α+ double-positive CD4+ T cells in the live EB vaccine groups was much higher than that in the nonprotected groups (Fig. 5C). The data demonstrated that IFN-γ+–producing CD4+ T cells that highly coexpress TNF-α were the most reliable correlate of immunity against C. muridarum infection and were predominantly induced by live but not dead EB immunization.

FIGURE 5.

The magnitude and quality of CD4+ T cell responses in vaccinated mice after C. muridarum challenge. EB-specific cytokine productions from splenocytes of vaccinated mice after challenge were analyzed by multiparameter flow cytometry. A, The total number of IFN-γ–, TNF-α–, or IL-2–producing CD4 T cells in 106 splenocytes. B, The fraction of IFN-γ EB-specific triple-, double-, and single-positive cells for each vaccine group. Four mice were in each group. C, The MFI of TNF-α EB-specific triple-, double-, and single-positive cells for each vaccine group. Shown are results representative of two experiments. D-EB, dead EBs; L-EB, live EBs.

Live EB-pulsed DCs present more C. muridarum MHC class II peptides compared with dead EB-pulsed DCs

Because DCs are essential to induce C. muridarum cellular immunity via presentation of pathogen-specific Ags to naive T cells, we hypothesized that DCs exposed to live versus dead EBs may present distinct populations of peptides that may correlate with protection against C. muridarum infection. We used an immunoproteomic approach to identify Chlamydia MHC class II peptides eluted from DCs pulsed with live EBs or dead EBs. Eluted peptides were sequenced using mass spectrometry. We identified 45 C. muridarum MHC class II-binding peptides from DCs pulsed with live EBs, but only 6 C. muridarum MHC class II-binding peptides from DCs pulsed with dead EBs (Table I). The 45 MHC class II-binding peptides identified in DCs pulsed with live EBs mapped to 13 distinct epitopes derived from 13 unique source proteins. The six MHC class II-binding peptides identified in DCs pulsed with dead EBs mapped to three distinct epitopes derived from three unique source proteins. The peptides derived from RplF and FabG were found in DCs pulsed with both live and dead EBs. The peptide AtpE was only found in DCs pulsed with dead EBs. There were 11 peptides, including PmpG and PmpE/F-2, found only in DCs pulsed with live EBs. Of note, our previous studies demonstrated that PmpG and PmpE/F-2 are immunodominant peptides/proteins that engender protective immunity against C. muridarum genital tract infection (19). We also compared the number of pathogen- and murine-derived MHC class II-bound peptides identified in DCs pulsed with live and dead EBs and found more peptides when the DCs were pulsed with live EBs. This was true for both C. muridarum and self-peptides and was more notable for C. muridarum-derived peptides than for self-peptides. The fold increase for pathogen-derived peptides from dead to live EB pulsing is 7.5 versus 2.2 for self-peptides (Table II). This suggests that DCs pulsed with live EBs present peptides via MHC more efficiently than do DCs pulsed with dead EBs, which in turn correlates with induction of better protective immunity by live EB immunization.

Table I.

MHC class II-bound C. muridarum peptides identified in DCs after 12 h pulsing with live and dead EBs using immunoproteomics

| Peptide Sequencea | Source Protein | Abbreviation |

|---|---|---|

| Live EBs | ||

| VKGNEVFVSPAAHIIDRPG (13) | Ribosomal protein L6 | RplF |

| SPGQTNYAAAKAGIIGFS (3) | 3-Oxoacyl-(acyl carrier protein) reductase | FabG |

| NAKTVFLSNVASPIYVDPA (1) | Polymorphic membrane protein G | PmpG |

| GAFHLFASPAANYIHTGS (5) | Polymorphic membrane protein F | PmpE/F-2 |

| GRDLNVTGPKIQTDVDL (7) | Hypothetical protein TC0420 | TC0420 |

| EGTKIPIGTPIAVFSTEQN (4) | Pyruvate dehydrogenase | TC0518 |

| GANAIPVHCPIGAESQ (3) | Elongation factor G | FusA |

| VFWLGSKINIIDTPG (1) | Elongation factor G | FusA |

| SVPSYVYYPSGNRAPVV (2) | Thiol-disulfide interchange protein | TC0884 |

| FEVQLISPVALEEGMR (2) | Elongation factor Tu | Tuf |

| YDHIIVTPGANADIL (1) | Oxidoreductase | TC0654 |

| LPLMIVSSPKASESGAA (1) | Metalloprotease | TC0190 |

| ISRALYTPVNSNQSVG (1) | Elongation factor Ts | Tsf |

| SRALYAQPMLAISEA (1) | Polymorphic membrane protein E | PmpE/F-1 |

| Dead EBs | ||

| VKGNEVFVSPAAHIIDRPG (4) | Ribosomal protein L6 | RplF |

| SPGQTNYAAAKAGIIGFS (1) | 3-Oxoacyl-(acyl carrier protein) reductase | FabG |

| KPAEEEAGSIVHNAREQ (1) | ATP synthase subunit E | AtpE |

Numbers in parentheses denote total number of peptides of varying length but consisting of the same core residues.

Table II.

Comparison of Chlamydia- and murine-derived MHC class II-bound peptides identified in DCs after 12 h pulsing with live and dead EBs

| Dead EBs | Live EBs | Fold Increase | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Murine (self) peptides | 527 | 1180 | 2.2 |

| Chlamydia peptides | 6 | 45 | 7.5 |

Discussion

Infection or immunization with viable intracellular pathogens typically induces immunological effects distinct from those elicited by inactivated organism (31). This also appears to be the case for Chlamydia (32, 33). For example vaccination of both humans and nonhuman primates with whole killed C. trachomatis resulted in limited protection with possible disease exacerbation upon reinfection (6, 7, 34). Strikingly, mice immunized with live C. muridarum developed complete protection (8, 35), whereas immunization with killed C. muridarum induced responses ranging from little to no protection (8), thereby providing a model system to investigate the underlying cellular and molecular basis for the failure of previous human and primate C. trachomatis vaccine trials. An understanding of differences in immune mechanisms elicited between live and dead organisms may serve to guide the future directions for C. trachomatis vaccine design.

There are two major findings reported from the present study. First, IFN-γ+–producing CD4+ T cells that highly coexpress TNF-α optimally correlated with protective immunity and were preferentially induced by live EB immunization. Second, exposure to live C. muridarum EBs induced DCs to present more pathogen-derived MHC class II peptides than did dead C. muridarum EBs.

CD4 Th1 effector cells clearly underpin Chlamydia immunity (13), and Igietseme et al. (23) originally demonstrated that adoptive transfer of a CD4 T cell clone specific to C. muridarum, which secreted both IFN-γ and TNF-α, resulted in resolution of chronic genital C. muridarum infection in nude mice. In contrast, a clone that produced IFN-γ alone was unable to resolve the infection in nude mice, even after 100 d, demonstrating that T cells that secrete multiple cytokines were substantially better at clearing infection than T cells with a limited cytokine profile. Building on these early promising results, we tested multiple cytokine secretion patterns at the singe cell level using flow cytometry.

When using multiparameter flow cytometry in other pathogen studies, multifunctional CD4+ T cells that cosecrete IFN-γ+, TNF-α, and IL-2 have been reported to better correlate with protection than IFN-γ+ single-positive secretion in Leishmania major (24) and Mycobacterium tuberculosis (25). Olsen et al. (36) also recently reported a high number of Ag-specific CD4+ T cells coexpressing IFN-γ and TNF-α in mice intranasally immunized with live C. muridarum, and in the current study, we demonstrate that IFN-γ+–producing CD4+ T cells that highly coexpress TNF-α were optimally correlated with protective immunity to C. muridarum genital tract challenge.

Multiple mechanisms could contribute to the enhanced protection to Chlamydia infection as mediated by multifunctional CD4+ T cells. First, multiple cytokines could have direct and synergistic antimicrobial action. In vitro studies have demonstrated that IFN-γ and TNF-α individually and synergistically in combination restrict intracellular Chlamydia growth (37, 38). Both IFN-γ and TNF-α activate inducible NO synthase in murine cells (39), and Robinson et al. (40) demonstrated that TNF-α synergistically enhanced IDO activity induced by IFN-γ at the level of transcription in human epithelial cells. Second, multifunctional CD4+ T cells may better correlate with protective immunity because they produce more cytokine on a per-cell basis, as recently shown in a study of Leishmania major (24). In our study, we also observed higher MFI values for IFN-γ and TNF-α among triple-and double-positive cells. Third, both IFN-γ and TNF-α upregulate MHC class II and ICAM-1 expression on human cervical and vaginal epithelial cells (41). Greater production of IFN-γ and TNF-α by multifunctional CD4+ T cells could thereby enhance recognition of Chlamydia-infected epithelial cells and T cell activation via TCR/peptide/MHC class II and LFA/ICAM-1 path-ways. It has been reported that physical contact between T cells and epithelial cells via LFA-1–ICAM-1 interactions are critical for epithelial NO production to chlamydiacidal levels (42). Lastly, Jayarapu et al. (43) reported that CD4+ Th1 cells restrict epithelial Chlamydia growth by both inducible NO synthase-dependent and degranulation-dependent mechanisms, and multifunctional CD4+ T cells may be superior to single cytokine-producing cells in their degranulation potential. For instance, Kannanganat et al. (44) reported that CMV-specific CD4 T cells underwent degranulation with ~50% of IFN-γ/TNF-α/IL-2 triple producers and IFN-γ/TNF-α double producers degranulating following Ag stimulation, compared with <15% of IFN-γ single producers. These data suggest that multifunctional CD4 T cells that coexpress IFN-γ and TNF-α preferentially degranulate compared with single IFN-γ producers and thus may possess better killing potential. In aggregate, the data suggest that vaccination that induces IFN-γ and TNF-α coexpressing CD4 T cells may represent the optimal correlate of protective immunity to C. trachomatis infection by one or more of these mechanisms.

Recently, we used an immunoproteomic approach to directly identify C. muridarum T cell peptides presented by APCs. Because DCs are essential to induce C. muridarum immunity via presentation of Ags to naive T cells, we reasoned that live and dead organism may induce presentation of different peptides. Accordingly, we compared the MHC class II-bound C. muridarum peptides identified in DCs 12 h after pulsing with live and dead organisms. We found that DCs pulsed with live EBs presented 45 MHC class II C. muridarum peptides that mapped to 13 proteins, including RplF, PmpG, and PmpE/F-2. These three C. muridarum T cell Ags have been previously identified as immunodominant. Moreover, vaccination with individual RplF, PmpG, or PmpE/F-2 recombinant proteins in mice engendered significant resistance to challenge infection in both the lung and genital tract models (19). In contrast, DCs pulsed with dead EBs led to the identification of only six MHC class II C. muridarum peptides that mapped to three proteins and included only one (RpIF) of the three immunodominant C. muridarum Ags. Among the 15 epitopes presented by DCs after 12 h pulsing with live or dead EBs, 5 (RplF, FabG, PmpG, PmpE/F-2, and TC0420) were previously identified when DCs were pulsed with live organisms for 24 h (18). Thus 10 new C. muridarum T cell epitopes (TC0518, FusA, TC0884, Tuf, TC0654, TC0190, Tsf, PmpE/F-1, AtpE; Table I) were identified in the current study.

Explanation for the different Ag repertoires presented by live and dead C. muridarum may relate to preferential patterns of protein expression by EBs and reticulate bodies. We reviewed data reported by Skipp et al. (45) on the expression pattern of proteins from replicating C. trachomatis and correlated those data with the epitopes identified from live versus dead EBs. We found that none of the identified C. muridarum source proteins was only expressed in reticulate bodies. We next examined the possibility that the source proteins of the epitopes identified from live EBs are more abundantly expressed during the reticulate body stage based on quantitative transcriptome data (46). Again, we observed no apparent association between mRNA expression levels and detection as a MHC class II binding peptide. Although the mechanism behind differential presentation is not yet known, the immunoproteomic data do demonstrate that the different protective immunity induced by live and dead C. muridarum is correlated with distinct peptide presentation by DCs.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that the cytokine secretion pattern and frequency of multifunctional T cells coexpressing IFN-γ, TNF-α, and/or IL-2 induced by live or dead C. muridarum vaccines correlated with the degree of protection against genital tract infection. Furthermore, DCs pulsed with live EBs presented more C. muridarum MHC class II peptides compared with dead EB-pulsed DCs. These findings provide mechanisms to explain the disparate protective immunity responses elicited by live and dead C. muridarum and should help guide future vaccine development for C. trachomatis.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant R01AI076483 (to R.C.B.).

We thank David Ko, Lindsey Laycock, and Gayle Thornbury in the Terry Fox Laboratory at the British Columbia Cancer Research Centre for providing flow cytometry services and technical assistance.

Abbreviations used in this article

- CpG-ODN

CpG-containing oligodeoxynucleotide

- DC

dendritic cell

- EB

elementary body

- IFU

inclusion-forming unit

- MFI

mean fluorescence intensity

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Starnbach MN, Roan NR. Conquering sexually transmitted diseases. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:313–317. doi: 10.1038/nri2272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brunham RC, Zhang DJ, Yang X, McClarty GM. The potential for vaccine development against chlamydial infection and disease. J Infect Dis. 2000;181(Suppl 3):S538–S543. doi: 10.1086/315630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Igietseme JU, Black CM, Caldwell HD. Chlamydia vaccines: strategies and status. BioDrugs. 2002;16:19–35. doi: 10.2165/00063030-200216010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brunham RC, Pourbohloul B, Mak S, White R, Rekart ML. The unexpected impact of a Chlamydia trachomatis infection control program on susceptibility to reinfection. J Infect Dis. 2005;192:1836–1844. doi: 10.1086/497341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Su H, Morrison R, Messer R, Whitmire W, Hughes S, Caldwell HD. The effect of doxycycline treatment on the development of protective immunity in a murine model of chlamydial genital infection. J Infect Dis. 1999;180:1252–1258. doi: 10.1086/315046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grayston JT, Wang SP. The potential for vaccine against infection of the genital tract with Chlamydia trachomatis. Sex Transm Dis. 1978;5:73–77. doi: 10.1097/00007435-197804000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grayston JT, Wang SP, Yeh LJ, Kuo CC. Importance of reinfection in the pathogenesis of trachoma. Rev Infect Dis. 1985;7:717–725. doi: 10.1093/clinids/7.6.717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lu H, Xing Z, Brunham RC. GM-CSF transgene-based adjuvant allows the establishment of protective mucosal immunity following vaccination with inactivated Chlamydia trachomatis. J Immunol. 2002;169:6324–6331. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.11.6324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schachter J, Caldwell HD. Chlamydiae. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1980;34:285–309. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.34.100180.001441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Su H, Messer R, Whitmire W, Fischer E, Portis JC, Caldwell HD. Vaccination against chlamydial genital tract infection after immunization with dendritic cells pulsed ex vivo with nonviable Chlamydiae. J Exp Med. 1998;188:809–818. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.5.809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rey-Ladino J, Koochesfahani KM, Zaharik ML, Shen C, Brunham RC. A live and inactivated Chlamydia trachomatis mouse pneumonitis strain induces the maturation of dendritic cells that are phenotypically and immunologically distinct. Infect Immun. 2005;73:1568–1577. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.3.1568-1577.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zaharik ML, Nayar T, White R, Ma C, Vallance BA, Straka N, Jiang X, Rey-Ladino J, Shen C, Brunham RC. Genetic profiling of dendritic cells exposed to live- or ultraviolet-irradiated Chlamydia muridarum reveals marked differences in CXC chemokine profiles. Immunology. 2007;120:160–172. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2006.02488.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brunham RC, Rey-Ladino J. Immunology of Chlamydia infection: implications for a Chlamydia trachomatis vaccine. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:149–161. doi: 10.1038/nri1551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Steinman RM, Pope M. Exploiting dendritic cells to improve vaccine efficacy. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:1519–1526. doi: 10.1172/JCI15962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hunt DF, Henderson RA, Shabanowitz J, Sakaguchi K, Michel H, Sevilir N, Cox AL, Appella E, Engelhard VH. Characterization of peptides bound to the class I MHC molecule HLA-A2.1 by mass spectrometry. Science. 1992;255:1261–1263. doi: 10.1126/science.1546328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Jong A. Contribution of mass spectrometry to contemporary immunology. Mass Spectrom Rev. 1998;17:311–335. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2787(1998)17:5<311::AID-MAS1>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Olsen JV, de Godoy LM, Li G, Macek B, Mortensen P, Pesch R, Makarov A, Lange O, Horning S, Mann M. Parts per million mass accuracy on an Orbitrap mass spectrometer via lock mass injection into a C-trap. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2005;4:2010–2021. doi: 10.1074/mcp.T500030-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karunakaran KP, Rey-Ladino J, Stoynov N, Berg K, Shen C, Jiang X, Gabel BR, Yu H, Foster LJ, Brunham RC. Immunoproteomic discovery of novel T cell antigens from the obligate intracellular pathogen Chlamydia. J Immunol. 2008;180:2459–2465. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.4.2459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu H, Jiang X, Shen C, Karunakaran KP, Brunham RC. Novel Chlamydia muridarum T cell antigens induce protective immunity against lung and genital tract infection in murine models. J Immunol. 2009;182:1602–1608. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.3.1602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Su H, Caldwell HD. CD4+ T cells play a significant role in adoptive immunity to Chlamydia trachomatis infection of the mouse genital tract. Infect Immun. 1995;63:3302–3308. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.9.3302-3308.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morrison SG, Su H, Caldwell HD, Morrison RP. Immunity to murine Chlamydia trachomatis genital tract reinfection involves B cells and CD4+ T cells but not CD8+ T cells. Infect Immun. 2000;68:6979–6987. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.12.6979-6987.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morrison RP, Caldwell HD. Immunity to murine chlamydial genital infection. Infect Immun. 2002;70:2741–2751. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.6.2741-2751.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Igietseme JU, Ramsey KH, Magee DM, Williams DM, Kincy TJ, Rank RG. Resolution of murine chlamydial genital infection by the adoptive transfer of a biovar-specific, Th1 lymphocyte clone. Reg Immunol. 1993;5:317–324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Darrah PA, Patel DT, De Luca PM, Lindsay RW, Davey DF, Flynn BJ, Hoff ST, Andersen P, Reed SG, Morris SL, et al. Multifunctional TH1 cells define a correlate of vaccine-mediated protection against Leishmania major. Nat Med. 2007;13:843–850. doi: 10.1038/nm1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Forbes EK, Sander C, Ronan EO, McShane H, Hill AV, Beverley PC, Tchilian EZ. Multifunctional, high-level cytokine-producing Th1 cells in the lung, but not spleen, correlate with protection against Mycobacterium tuberculosis aerosol challenge in mice. J Immunol. 2008;181:4955–4964. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.7.4955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wille-Reece U, Flynn BJ, Loré K, Koup RA, Miles AP, Saul A, Kedl RM, Mattapallil JJ, Weiss WR, Roederer M, Seder RA. Toll-like receptor agonists influence the magnitude and quality of memory T cell responses after prime-boost immunization in nonhuman primates. J Exp Med. 2006;203:1249–1258. doi: 10.1084/jem.20052433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liew FY, Li Y, Millott S. Tumor necrosis factor-α synergizes with IFN-γ in mediating killing of Leishmania major through the induction of nitric oxide. J Immunol. 1990;145:4306–4310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Caldwell HD, Kromhout J, Schachter J. Purification and partial characterization of the major outer membrane protein of Chlamydia trachomatis. Infect Immun. 1981;31:1161–1176. doi: 10.1128/iai.31.3.1161-1176.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang X, HayGlass KT, Brunham RC. Genetically determined differences in IL-10 and IFN-γ responses correlate with clearance of Chlamydia trachomatis mouse pneumonitis infection. J Immunol. 1996;156:4338–4344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Inaba K, Inaba M, Romani N, Aya H, Deguchi M, Ikehara S, Muramatsu S, Steinman RM. Generation of large numbers of dendritic cells from mouse bone marrow cultures supplemented with granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor. J Exp Med. 1992;176:1693–1702. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.6.1693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mackaness GB. The relationship of delayed hypersensitivity to acquired cellular resistance. Br Med Bull. 1967;23:52–54. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a070516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang D, Yang X, Lu H, Zhong G, Brunham RC. Immunity to Chlamydia trachomatis mouse pneumonitis induced by vaccination with live organisms correlates with early granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor and interleukin-12 production and with dendritic cell-like maturation. Infect Immun. 1999;67:1606–1613. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.4.1606-1613.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taylor HR. Development of immunity to ocular chlamydial infection. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1990;42:358–364. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1990.42.358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grayston JT, Gale JL, Yeh LJ, Yang CY. Pathogenesis and immunology of trachoma. Trans Assoc Am Physicians. 1972;85:203–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yu H, Jiang X, Shen C, Karunakaran KP, Jiang J, Rosin NL, Brunham RC. Chlamydia muridarum T-cell antigens formulated with the adjuvant DDA/TDB induce immunity against infection that correlates with a high frequency of γ interferon (IFN-γ)/tumor necrosis factor α and IFN-γ/interleukin-17 double-positive CD4+ T cells. Infect Immun. 2010;78:2272–2282. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01374-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Olsen AW, Theisen M, Christensen D, Follmann F, Andersen P. Protection against Chlamydia promoted by a subunit vaccine (CTH1) compared with a primary intranasal infection in a mouse genital challenge model. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e10768. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Holtmann H, Shemer-Avni Y, Wessel K, Sarov I, Wallach D. Inhibition of growth of Chlamydia trachomatis by tumor necrosis factor is accompanied by increased prostaglandin synthesis. Infect Immun. 1990;58:3168–3172. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.10.3168-3172.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shemer-Avni Y, Wallach D, Sarov I. Inhibition of Chlamydia trachomatis growth by recombinant tumor necrosis factor. Infect Immun. 1988;56:2503–2506. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.9.2503-2506.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Amber IJ, Hibbs JB, Jr, Taintor RR, Vavrin Z. Cytokines induce an L-arginine-dependent effector system in nonmacrophage cells. J Leukoc Biol. 1988;44:58–65. doi: 10.1002/jlb.44.1.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Robinson CM, Shirey KA, Carlin JM. Synergistic transcriptional activation of indoleamine dioxygenase by IFN-γ and tumor necrosis factor-α. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2003;23:413–421. doi: 10.1089/107999003322277829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fichorova RN, Anderson DJ. Differential expression of immunobiological mediators by immortalized human cervical and vaginal epithelial cells. Biol Reprod. 1999;60:508–514. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod60.2.508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Igietseme JU, I, Uriri M, Hawkins R, Rank RG. Integrin-mediated epithelial-T cell interaction enhances nitric oxide production and increased intracellular inhibition of Chlamydia. J Leukoc Biol. 1996;59:656–662. doi: 10.1002/jlb.59.5.656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jayarapu K, Kerr M, Ofner S, Johnson RM. Chlamydia-specific CD4 T cell clones control Chlamydia muridarum replication in epithelial cells by nitric oxide-dependent and -independent mechanisms. J Immunol. 2010;185:6911–6920. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kannanganat S, Ibegbu C, Chennareddi L, Robinson HL, Amara RR. Multiple-cytokine-producing antiviral CD4 T cells are functionally superior to single-cytokine-producing cells. J Virol. 2007;81:8468–8476. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00228-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Skipp P, Robinson J, O’Connor CD, Clarke IN. Shotgun proteomic analysis of Chlamydia trachomatis. Proteomics. 2005;5:1558–1573. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200401044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Belland RJ, Zhong G, Crane DD, Hogan D, Sturdevant D, Sharma J, Beatty WL, Caldwell HD. Genomic transcriptional profiling of the developmental cycle of Chlamydia trachomatis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:8478–8483. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1331135100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]