Abstract

Health disparities are a major concern in the United States. Research suggests that inequitable distribution of money, power, and resources shape the circumstances for daily life and create and exacerbate health disparities. In rural communities, inequitable distribution of these structural factors seems to limit employment opportunities. The Sustainable Livelihoods framework, an economic development model, provides a conceptual framework to understand how distribution of these social, economic, and political structural factors affect employment opportunities and community health in rural America. This study uses photo-elicitation interviews, a qualitative, participatory method, to understand community members perceptions of how distribution of structural factors through creation and maintenance of institutional practices and policies, influence employment opportunities and, ultimately, community health for African Americans living in rural Missouri.

Introduction

Researchers have documented health disparities by both race/ethnicity and rurality (Center for Rural Health Practice, 2004; Pappas, Queen, Hadden, & Fisher, 1993; Williams, 2005). National and international studies show a link between these health disparities and social, economic, and political conditions of daily life, often referred to as social determinants of health (Baker, Metzler, & Galae, 2005; Commission on Social Determinants of Health, 2008; Graham, 2004; Marmot & Wilkinson, 1999; Picket & Pearl, 2001; Smith, Hart, Watt, Hole, & Hawthorne, 1998). The distribution of money, power, and resources are the structural factors that contribute to disparities in health outcomes through their construction of the circumstances in which people are born, live, work, and play (Commission on Social Determinants of Health, 2008). The inequitable distribution of these structural factors contributes to health disparities. Employment, an element of an economic and social condition of life, contributes to health disparities, especially in minority, rural communities. Studies show that unemployment, low wage employment, and poor job conditions are associated with increased morbidity and mortality (Adler, et al., 2007; Dooley, Feilding, & Levi, 1996; Jin, Shah, & Svoboda, 1995; Kessler, House, & Turner; Martikainen, 1990; Mathers & Schofield, 1998). Limited sources of employment along with racial segregation in rural communities in the southern United States (Probst, et al., 2002) may put African Americans living in these areas at even greater risk of developing chronic diseases.

Understanding how money, power, and resources are distributed within a community and the roles institutional practices and policies play in determining this distribution is necessary for the identification of strategies to address social determinants. Frameworks have been developed that identify possible pathways of influence (Anderson, Scrimshaw, Fullilove, Fielding, & the Task Force on Community Preventive Services, 2003; Krieger, 2008a, 2008b; Solar & Irwin, 2007). For example, a framework developed by the World Health Organization’s Commission on Social Determinants of Health indicates that access to safe and available jobs is a product of complex social, historical, and economic processes that govern our daily living (Krieger, 2008a, 2008b; Solar & Irwin, 2007). This framework and others suggest pathways through which social determinants of health (e.g., employment) and structural factors shape the conditions in which we live, work, and play (Krieger, 2008a).

Frameworks are essential for understanding these complex relationships. However, many of these frameworks have been developed within academia and may not help local communities identify the factors at play in shaping health and well being in a specific community. This is particularly important to consider when trying to understand how distribution of structural factors affects social determinants of health in rural minority communities. These communities need to identify locally relevant structural factors that if altered could have the greatest positive impact on health.

The Sustainable Livelihoods Framework provides an opportunity to identify structural factors (i.e., money, power, and resources) and their influence on health in rural communities. The framework focuses on the link between ways of making a living (i.e., employment) and community health in the context of other social, political, and economic factors experienced by rural communities. Since the 1990’s, rural communities outside of the US have been using this framework to understand how ways of making a living are shaped and how availability of different ways to make a living affect health and well being in poor rural communities. However, less work has been conducted to assess the utility of this framework within rural communities in the United States.

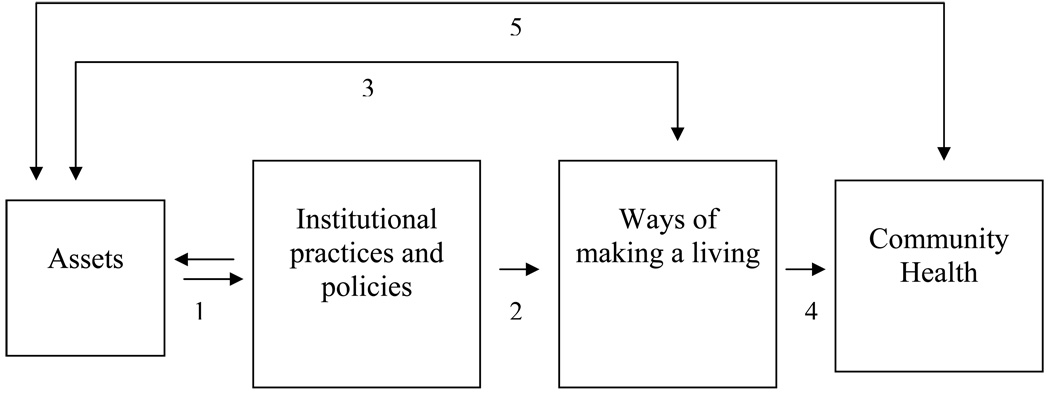

The Sustainable Livelihoods framework (see Figure 1) suggests that community assets (i.e., resources, money) influence the creation and maintenance of institutional policies and practices. Policy and practices subsequently shape the community’s resources, opportunities to make a living and the health and well being of the community (Chambers & Conway, 1992; Scoones, 1998). This article describes how the Sustainable Livelihoods framework was used in conjunction with a participatory, qualitative method to understand community perceptions of the influence of complex social, economic, and political factors on employment opportunities and community health for African Americans in rural Missouri.

Figure 1.

Modified Sustainable Livelihoods Framework (Department of International Development, 2007)

The setting

Men on the Move (MOTM), a community-based participatory research project, is located in Pemiscot County, MO (National Institutes of Health, R24 MD001590). Pemiscot County is a rural area in the “Bootheel” region of Missouri. Compared to the state, this rural county has a higher percentage of residents living in poverty (24% v. 11.3%), lower percentage of high school graduates (78.5% v. 85.5%) (Office of Social and Economic Data Analysis, 2007) and a higher rate of unemployment (8.2% v. 5.4% in 2005) (United States Census Bureau, 2007). Although these data are not available by race, studies show that African Americans living in rural areas are more likely to be poor and have lower academic achievement than their white counterparts (Toldson, 2008).

Chronic disease rates in Pemiscot County are among the highest in the state. From 1997–2007, all cause mortality in Pemiscot County was 1120 per 100,000 as compared to 890.5 per 100,000 for Missouri as a whole. (Missouri Department of Health and Senior Services, 2008). Similarly, the heart disease mortality rate in Pemiscot County (428.5) was 60% higher than the rate for Missouri (262.7) (Missouri Department of Health and Senior Services, 2008). Pemiscot County has the largest percent of African American residents (25%) living in a rural Missouri area and a significantly higher percentage of African American residents than the state as a whole (11%) (Missouri Economic Research and Information Center, 2006). While Pemiscot County experiences higher mortality rates than most counties in Missouri, rates for African Americans are higher still (Missouri Department of Health and Senior Services, 2008).

Men on the Move was developed to respond to the health and social inequities experienced by African Americans in Pemiscot County. The Men on the Move community-academic partnership consists of community members in Pemiscot County and researchers at Saint Louis University. The premise for the development of MOTM is that while individual health is a priority, the reality of improving health is improbable unless the social causes of poor health are addressed. When discussing the causes of poor health of African Americans in Pemiscot County, the partnership identified multiple determinants. Community partners consistently pointed to social inequities as the pinnacle. Specifically, community partners highlighted limited access and availability of employment for African Americans, especially African American men, as a key contributor to current health disparities in Pemiscot County.

Methods

The Saint Louis University Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Participants

Thirteen African American women and eleven African American men (n= 24) who resided in Pemiscot County, Missouri, participated in this study. To be eligible to participate, individuals had to be African American, over the age of 18 years and a resident of Pemiscot County for at least 15 years. Using a snowball sampling technique, key informants (i.e., community members with established relationships in the community) identified participants who could contribute rich information about employment in Pemiscot County (Miles & Huberman, 1994). Table 1 provides a demographic overview of participants.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics compared with Missouri population

| Demographic Characteristics | Male participants (n=11) |

Female participants (n=13) |

Missouri* | United States | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | Men | Women | |||

| Mean age | 41 | 45 | -- | -- | ||

| Average years as a resident | 28 | 40 | -- | -- | ||

| Educational attainment | ||||||

| Less high school | 2 (18%) | 2 (15%) | 25% | 28% | 16% | 14% |

| High school graduate | 5 (45%) | 1(8%) | 29% | 32% | 29% | 29% |

| Some college | 3(27%) | 6(46%) | 32% | 28% | 27% | 30% |

| College graduate | 0 | 4(31%) | 14% | 12% | 28% | 27% |

| Refused | 1(9%) | 0 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Job status | ||||||

| Employed for wages | 5 (45%) | 9 (69%) | -- | -- | ||

| Self employed | 1 (9%) | 1(8%) | -- | -- | ||

| Out of work | 1 (9%) | 2(15%) | -- | -- | ||

| Odd jobs/handy work | 1 (9%) | 0 | -- | -- | ||

| Retired | 0 | 1(8%) | -- | -- | ||

| Unable to work | 1(9%) | 0 | -- | -- | ||

| Stay at home parent | 1(9%) | 0 | -- | -- | ||

| Refused | 1(9%) | 0 | -- | -- | ||

| Household income | ||||||

| Less than $9,999 | 3 (27%) | 1 (8%) | 20% | 7% | ||

| $10,000 – 14,999 | 0 | 3 (23%) | 9% | 5% | ||

| $15,000 – 19,999 | 1(9%) | 1 (8%) | 18% | 11% | ||

| $20,000 – 24,999 | 2 (18%) | 0 | ||||

| $25,000 – 34,999 | 4 (36%) | 3(23%) | 30% | 24% | ||

| $35,000 – 49,999 | 0 | 3 (23%) | ||||

| $50, 000 and above | 0 | 1(8%) | 23% | 52% | ||

| Refused | 1(9%) | 1 (8%) | -- | -- | ||

Data for entire Missouri population

Data Collection

Photo-elicitation interviews were conducted with the participants. Photo-elicitation is a qualitative method which prompts discussion by asking participants to review and discuss photographs (Harper, 2002). The photo-elicitation interview questions were guided by the Sustainable Livelihoods Framework. The photo-elicitation protocol was developed and pilot-tested to determine whether the questions were understood by participants, captured the major SL constructs and were open ended. A photographer with limited knowledge of the area took photographs of Pemiscot County. The photographer was given a list, generated collectively by partners, of the types of scenes or structures related to employment (e.g., local stores, national stores and abandoned businesses) to capture and a community member guided the photographer to important sites within the community. Approximately fifty photographs were taken and reviewed by academic and community members of the research team. The research team chose eight images that best captured employment issues for use in the photo-elicitation process. Eight by ten inch photographs were printed in black and white color.

Two male and two female photo-elicitation groups met to discuss employment. Participants read and signed consent forms. Each photo-elicitation session lasted approximately 90 minutes. Two recording devices were used to audiotape the interviews for transcription and analysis. Two trained facilitators conducted all four photo-elicitation interviews. Prior to beginning the photo-elicitation interviews, the participants completed a short demographic questionnaire. The questions asked about the participants’ age, education level, job status, income level and work history.

In the interviews, eight employment photographs were presented. The photographs were presented in two phases. The first phase included four photographs assumed to elicit the employment challenges (e.g., photograph of abandoned businesses along Main Street) while the second phase included four photographs assumed to reflect employment opportunities (e.g., photograph of a large manufacturer in the county). After an initial reflection period, trained facilitators led participants through a structured dialogue. The questions guiding the dialogue included asking participants to provide a description of the photograph, personal or community meaning, the factors contributing to the situation (i.e., types of capital), institutional practices or policies that influenced the conditions described or represented by the photograph, and potential community health consequences. Throughout the interviews, facilitators asked participants to clarify the intended meaning of comments and provide more information when necessary. Referred to as member checking, this process helps to eliminate facilitator assumptions about the meaning of participants’ comments (Baker & Motton, 2005; Lincoln & Guba, 1985).

Data Analysis

Each photo-elicitation interview was audio-taped with the permission of the participants. Project staff transcribed the tapes verbatim. Each transcript was reviewed for errors and corrected before beginning analysis. Atlas.ti, a qualitative analysis software package (Muhr, 2004), was used to facilitate management, coding, and sorting of data.

A start list of codes was created based on the categories established by the Sustainable Livelihoods framework including forms of capital, institutional practices and policies, livelihood strategies, and health outcomes. Code definitions were determined by the Sustainable Livelihoods framework to provide coders with a common understanding of the codes (Miles & Huberman, 1994). Coders began the coding process with a start list, a technique commonly used in focused coding (Strauss & Corbin, 1998). As analysis progressed, codes were revised and new codes were added when appropriate. Allowing for revision is a necessary step in the analysis process (Miles & Huberman, 1994).

The transcripts were coded by an initial coder and reviewed by a second coder, both of whom had been trained in qualitative methods. This approach is commonly used to enhance credibility because it challenges the initial coder’s biases and challenges the coders to draw common conclusions supported by data (Lincoln & Guba, 1985). After coding was checked for appropriateness, reports were subsequently generated by Atlas.ti to identify all quotes assigned to each code and determine the fit of the quotation within the code. Referred to as chunk checking, this step allows the researcher to determine if a code has broken down or quotes no longer fit within a code (Miles & Huberman, 1994). All coding decisions were documented to provide a record, or audit trail, of the data analysis process (Lincoln & Guba; Miles & Huberman).

Once the codes were finalized and quotes were appropriately assigned to codes, matrices were developed. Matrices are data display tools used to help a researcher understand relationships or patterns in the data and begin to draw conclusions about the data (Miles & Huberman, 1994). Matrices were developed to understand the relationship between codes (e.g., the relationship between financial capital and institutional practices) based on co-occurrence of the codes in the data, and emergent themes were identified. Using the matrices, written summaries for each code (e.g., financial capital) and the relationships between codes (e.g., relationship between financial capital and institutional practices) were developed. The summaries were reviewed by team members to test researcher assumptions and chunk checking was conducted when questions were raised. The written summaries were reviewed and revised to eliminate subtleties and focus on the main themes (Wolcott, 2001).

Findings

The Sustainable Livelihoods framework was used to inform the photo-elicitation process. The findings will be presented to relate to each construct. First, the findings will describe how community participants discussed community health. Then, the findings will be presented backwards along the framework to aid an understanding of how the state of community health is influenced by employment, the institutional practices and policies that exist and the community assets that influence the framework’s other constructs.

Community health

The participants noted that the general lack of opportunities in Pemiscot County contribute to heart disease. One participant noted,

I think the person that once he’s turned down and doesn’t have any, doesn’t have that desire to go on, in black people we develop heart problems, high blood pressure….and that can affect your health a lot.

The participants also noted that people, especially young men, develop strategies like bad eating habits and alcohol and drug use to cope. Others make sexual decisions that make them feel good, but may lead to teenage pregnancy or HIV.

So, they turn to sex. They turn to drugs. They turn to alcohol. Whatever is … I guess it… what does it do? What am I trying tell….it makes them feel good at the time, just for that moment, it is good. And then in the end it’s deadly. It’ll kill ‘em. I been tellin’ ‘em all you better protect it or put it up. One of the two. AIDS is real around here. It is really real.

Community members also listed loss of hope, depression, low self-esteem and stress as outcomes that result from living in a community with few opportunities. Community participants explained that if a person cannot get a job and use his or her skills and knowledge, he or she begins to feel depressed and may develop low self-esteem.

I think it [lack of available jobs], it produces low self esteem. I mean these pictures speak to lessening access. Not enough access. And what I see is for one thing the low self esteem that it produces in our men and then looking at the effects of that when there are no jobs, when jobs aren’t accessible, then comes stress levels. Then they start abusing drugs and alcohol.

The community participants recognized that the outcomes are not restricted to individuals but the community is hurt as a whole. The participants stated that when people feel hopeless and depressed, they stop participating in the community.

You got a lot of fragmented people. People stop… a lot people just kind of stay to themselves. Don’t have anything to do with anyone. Don’t attend certain functions with everyone. Don’t feel like it. I hear all the time even down to voting. Why should I? They gonna do what they wanta do anyway. This is a depressed person, man. They lost the understanding that there’s power even in that one vote. But, that’s…it’s fragmented. It’s separated. It can shut down. It’s bad but that’s kinda how it is.

Ways of making a living

Employment refers to employer-based full or part-time, legal employment and related activities. The community participants noted individuals are employed as security officers, doctors, dentists, truck drivers, and managers. Yet, the participants said that there are not enough opportunities for regular employment, especially “respectful, long term, good paying jobs.” Moreover, even when jobs are available not everyone, especially those with felony charges, has access to them. One community participant explains, “if you’ve ever been convicted of a felony, they won’t hire you.”

Two other strategies to make a living, self-employment and migration, emerge when these other employment opportunities are limited. Self-employment is defined as a person working for oneself, legally or illegally, to generate assets. The men noted that self-employment includes opportunities to make a living by depending on oneself, for example, cutting grass or running errands.

Ok, if you won’t hire me, I am smart enough I can find something to do for myself and make a living. There’s a lot of opportunities. It don’t matter if it’s cutting grass or running errands, I can do something for myself. That’s the other side of that.

The women explained that without good paying regular employment opportunities, men turn to illegal activities (e.g., selling drugs) to make a living.

I think young men are finding other ways to make their money and you know what, what route they’re going….Self-employment… selling drugs.

Migration occurs when someone leaves the community to find employment or other opportunities to make a living in another community. The community participants explained that without businesses and therefore jobs, people feel they have to leave the community to pursue employment opportunities.

Well, if there’s nothing here and businesses don’t want to come here look around. The buildings are decayed and there’s no opportunities. What you hear basically is, “you got to leave here because there’s nothing here. There’s nothing to do here. There’s no jobs here. You can’t make any money here.”

Institutional practices and policies

The Sustainable Livelihoods framework suggests that institutional regulation or influence is exerted through practices and policies. The participants’ description of practices and policies is somewhat vague. The participants noted that within Pemiscot County inappropriate or inadequate implementation of policies leads to concerns about practices. In particular participants noted concerns that practices tend to develop when policies are a1pplied differently to the African American and white community. Participants noted that while a policy may be fair, the inconsistent implementation of the policy tends to favor whites in power while creating challenges for African Americans and poor whites.

The policy is… is double standard…they don’t enforce across the board. They (the policies) are reasonable but they’re not enforced across the board. The double standard is between the whites and the African Americans. And sometimes poor whites get the same. So, it’s not just African Americans. Not all together, not all together. Uh-huh.

The community participants also noted that policies need to be changed but that many people do not take the initiative to engage in the process of policy change.

A lot these policies need to be changed but now they put in the form of government and the form of voting and the form of not enough people petition. It won’t get changed. And that’s why. Cuz’ a lot of these thing won’t get changed until you have people that are willing and enough people that are willing to march on it or to speak on it. And, you know, to write to congress. You know, it’s a process. They want you to go through this process. A long process to keep …they try to frustrate you by trying to get something done.

Assets

According to the Sustainable Livelihoods framework, assets can be divided into five types of capital, financial (i.e., cash, savings), human (i.e., knowledge and skills), natural (i.e., rivers, air), physical (i.e., roads, transportation system), and social (i.e., relationships of trust and reciprocity) (Department of International Development, 2007; Hancock, 2001; Kawachi, Kennedy, & Glass, 1999; Roseland, 1998). During the discussions, the participants identified an additional form, market capital, which captures business (i.e., buying, selling, and/or trading of goods and services) and business development.

The participants emphasized the lack of capital within their community (see Table 2). For example, participants noted that there is limited access to financial capital in the form of loans. “You could have money in that bank and still not get a loan.” They also mentioned that children do not have the skills (human capital) they need to succeed in life.

Can’t read, can’t write. Let me put that in there. Once they graduate they do not know how to read or write. It is not something that I’ve heard, it is something that I’ve seen.

Table 2.

The state of assets in Pemiscot County, Missouri

| Form of capital |

Definition | Explanation of state |

Example quote |

|---|---|---|---|

| Financial | Cash, savings, liquid assets | People are not making money | Because people aren’t making money. |

| Limited access to external funding (e.g., loans, grants, scholarships) |

You could have money in that bank and still not get a loan. In Pemiscot County you don’t get a scholarship unless you’re a good football player or you an alright basketball player you might go to SEMO. |

||

| Human | Knowledge, skills and abilities | Children do not have the basic skills they need to succeed | Can’t read, can’t write. Let me put that in there. Once they graduate they do not know how to read or write. It is not something that I’ve heard, it is something that I’ve seen. |

| Market | Business and business development | Loss of downtown businesses | I remember as a little girl there were all kinds of stores downtown, you know, that we went to even though when I was a little girl black people had to go in a certain door and be in a certain part of the store but we still got a chance to go in. You know. That’s, that’s my memory. |

| Loss of African American businesses |

P1: We used to have from Bess, Twelfth street back to what they call Fifteenth street now, back to Franklin, we used to have black businesses. P2: Lucrative black businesses. |

||

| Natural | Land, water, air quality, biodiversity | Limited access to land | This factory that went to Blytheville that wanted to come here, they wouldn’t sell them no land. |

| River underutilized | It has potential. I don’t think our river ways have been used to their fullest potential when it comes to distribution, so. We know that it’s an asset but I think it’s under utilized. | ||

| Physical | Manmade, physical infrastructures | Buildings are in poor condition | These other buildings are in such bad shape. I know the old movie theater, it has asbestos. It is time to tear that spot down. |

| No public transportation and access to personal transportation is limited |

As far as roads, as far as transportation, I always said you can walk anywhere in Pemiscot County. A car ride any where is but five minutes and that’s pretty much the same in Hayti. A lot of these guys like you said don’t have transportation. |

||

| Social | Relationships built on trust and reciprocity | People are not coming together |

We had neighborhood parents. They might not have been related to you but they knew your parents. They knew you. They watched you. If they saw you off somewhere doing something they could correct you and took you home. Most of the people they don’t come together. I had worked in the community all my jobs. |

| Hope that if people come together things can change | If we get together as a community, we start voting, we find somebody that’s not just for the hierarchy of Pemiscot County. We find somebody that’s for everybody, Pemiscot County as a whole, and vote them in, then maybe we see some changes. |

Despite an emphasis on the lack of assets, participants were able to identify opportunities to build capital. For example, one participant noted that the Mississippi River is an underutilized asset. When discussing the river, the participant said, “we know that it’s an asset but I think it’s underutilized.” The participants also discussed the potential to build social capital. One participant said that if people come together, a demonstration of social capital, and vote, they can create change.

If we get together as a community, we start voting, we find somebody that’s not just for the hierarchy of Pemiscot County. We find somebody that’s for everybody, Pemiscot County as a whole, and vote them in, then maybe we see some changes.

The links

With a clear understanding of the state of assets, institutional practices and policies, ways of making a living and community health, this section demonstrates the participants’ perception of how these factors influence each other in Pemiscot County. Although the community participants provided multiple examples of how they perceive the constructs in the framework to be linked, this section will use one example to demonstrate the link. The links are labeled in Figure 1 and Table 3 provides quotes to support the links discussed.

Table 3.

Data supporting the links between Sustainable Livelihoods Pathways

| Links | Explanation | Supporting quote |

|---|---|---|

| Link 1. Assets to institutional practices and policies | People with financial assets in the community are able to shape practices and/or policies about business development. The decisions made in turn limit business develop and financial capital for others in the community. | One thing for sure is that maybe some people in power, some people that have the money to influence the people in power will keep it…for example, when there are businesses looking at this area to come into and offer wages higher than what’s being paid here, they want to keep that down. And, that has happened in the past. |

| Link 2. The affect on ways of making a living | When practices keep new businesses from developing, this alters the choices people have to make a living. Some feel they cannot make enough money doing the jobs that exist. As a result, some choose to leave the community and others choose self employment. |

So you got boys saying, brother, for me, I can’t buy… how much them shoes cost? P2: $100 shoes P1: Them $100 shoes working for McDonalds. So what do they do? They sell drugs. P2: Self-employed. P1: They get self-employed and they sell drugs. They see that these people that still got these part time jobs are black. And kids say well I’m not going to come here. I got my degree I teach somewhere else. |

| Link 3. How choices about ways to make a living influence asset development | When people leave the community or choose illegal ways of making a living, the community loses role models. Further when there are few jobs in the community and education does not lead to better jobs, young people look for alternate ways of making a living. |

I got my degree I teach somewhere else. Now, you don’t want to discourage them from leaving. Why not come back here, like pastor said, to identify with kids in the neighborhood. You know, and he said, I had a teacher, a sixth grade teacher, Mr. Wiley. Mr. Wiley…we stayed in the projects, Mr. Wiley would come out there with us. He would play ball with us. He would come out there and talk with us. You know, I couldn’t wait to get to his class. You know, because it was encouragement to me and … If you leave education alone you get left behind. They not looking at the education like they saying. They may be looking at the football field. If you are athletically inclined? Got it and you don’t have it up there. They look at that money. They don’t care. They’ll give you money to go to college. Perhaps you goin’ professional. |

| Link 4. Affect on community health | Despite having assets like education, practices and policies have created a situation in which there are few choices about how one will make a living. Many people feel hopeless and depressed. | And a lot of these people are great people, intelligent people. Just gettin’ doors closed in their faces, like, just lose all hopes and dreams. And you have people that have went to college and have degrees and you know what I am gonna come back to where my family is and you know, you get here and bam. You have been around here a couple years and then it’s like, man things are not happening. You forget about at times, you can fall to a state of forgetfulness of I do have this degree or I did go out and do this. You get caught up around your environment or what’s going on. And for a long, ten or fifteen years will pass by and you find yourself still digging. And you’ll be like man what happened. Because I see people like what happened. And, I guess it’s that state they fall into depression, not able to find the type of work they’re looking for and want to be in this area. |

| Link 5. The final pathway – the relationship between assets and community health | People who feel hopeless and depressed, stop participating which depletes the power of social capital. | You got a lot of fragmented people. People stop… a lot people just kind of stay to themselves. Don’t have anything to do with anyone. Don’t attend certain functions with everyone. Don’t feel like it. I hear all the time even down to voting. Why should I? They gonna do what they wanta do anyway. This is a depressed person, man. They lost the understanding that there’s power even in that one vote. But, that’s…it’s fragmented. It’s separated. It can shut down. It’s bad but that’s kinda how it is. |

Link 1: Assets and institutional practices and policies

The SL framework indicates that the influence between assets and the development and maintenance of practices and policies is reciprocal. In accordance with the SL framework, our data suggest that people with power (e.g., money) in the community are able to determine which businesses are allowed to develop in the county (see Table 3). Money is a component of financial capital, a type of asset. In this instance, financial capital shapes a practice or policy around business development. This practice or policy regulates the development of new business. Business development is a component of market capital, another type of asset. This example demonstrates the reciprocal relationship between assets and institutional practices and policies.

Link 2: Assets and institutional practices and policies affect on ways of making a living

Building on the previous example, the participants noted that when powerful people in the community (i.e., those with assets) are able to keep new businesses out of the community (i.e., practice or policy) they are altering the ways people have to make a living. With few opportunities for regular employment and no new jobs being created, people find other ways of making a living. Some participants noted that people feel like they need to leave the community because there are no opportunities for them. Another participant explained that others choose self-employment, which includes illegal activity.

Link 3: How choices about ways to make a living influence asset development

The choices about how one will make a living may also influence the development of assets. The participants noted that the community loses positive role models for the children when people leave the community or choose illegal ways of making a living. Positive role models are a key building block for social capital and an important community asset. On the other hand, when the development of skills and knowledge through education (asset related to human capital) does not lead to jobs, the participants said that young people in the community focus on ways of making a living, such as athletics, that are not dependent on education. This underscores the reciprocal links between assets and ways of making a living.

Link 4: Lack of ways to make a living and the affect on community health

Participants connected poor community health outcomes to a lack of ways of making a living. One participant noted that many people in Pemiscot County do not have opportunities to make a living and feel hopeless and depressed, despite having a college education.

And a lot of these people are great people, intelligent people. Just gettin’ doors closed in their faces, like, just lose all hopes and dreams. And you have people that have went to college and have degrees and you know what I am gonna come back to where my family is and you know, you get here and bam. You have been around here a couple years and then it’s like, man things are not happening. You forget about at times, you can fall to a state of forgetfulness of I do have this degree or I did go out and do this. You get caught up around your environment or what’s going on. And for a long, ten or fifteen years will pass by and you find yourself still digging. And you’ll be like man what happened. Because I see people like what happened. And, I guess it’s that state they fall into depression, not able to find the type of work they’re looking for and want to be in this area.

Link 5: The relationship between community health and assets

Community health, either excellent or poor, is not an endpoint in the SL framework. It, too, feeds back to assets and institutional practices and policies. As one participant noted, when people feel hopeless and depressed they do not participate and the community is “fragmented.” This fragmentation is a barrier for building social capital and decreases the likelihood that the community will come together to change policies.

It is important to note that assets play a special role in the SL framework. Assets have relationships of influence with the other components. In relationship to community health, the state of assets partially determines the state of community health. As noted by the participants, assets in the form of money, skills, businesses, rivers, roads, and close social relationships are necessary to improve community health.

Discussion

The photo-elicitation interviews shed light on community members’ perception of how distribution of structural factors affects employment and community health in Pemiscot County. The participants discussed in more detail how institutional policies and practices have regulated the distribution of key structural factors. The participants indicated that the African American community within Pemiscot County has had difficulty maintaining and developing assets. The participants noted that, historically, there was a thriving business district (market capital) in the African American community that included business leaders (i.e., doctors, restaurant owners). Strong teachers (human capital) encouraged the use and development of social capital. The participants explained that over time market and human capital has diminished and people (i.e. African American teachers) have migrated out of the area. As a result, existing horizontal social capital (within the African American community) has diminished and vertical social capital (between the African American community and the white community) has not improved as demonstrated by the lack of African American leadership positions (e.g., teachers, city council members).

Unfortunately, lack of employment and devaluation of education contributes to a larger economic problem. The participants noted that high poverty, a result of unemployment, has weakened the customer base and businesses have closed. Consequently, they noted that this has led to the depreciation of buildings, making it difficult for community members to find space to develop new businesses. The participants identified the recruitment and attainment of outside business investors as a challenge as well. Business investors look for communities with job opportunities for spouses or significant others transferring to the area as well as a prepared workforce (Johnson, Parnell, Santos, & Crutchfield, 2006). With limited employment and a less educated workforce, Pemiscot County has trouble attracting new business.

Institutional practices and policies have played a contributing role in Pemiscot County. As perceived by the participants, practices and policies initiate the loss of capital and control job opportunities, particularly, for low income African Americans. For example, as noted by participants, people with power influence decision-making about business development which in turn influences job wages and employment opportunities. One participant explained that she encouraged the city to bring a factory into the area instead of a casino. A factory would provide people with an opportunity to work and make money. The city chose the casino. The woman noted that the casino provides an opportunity for poor people in the community to “spend the little money they have at the casino trying to win money because they do not have any opportunities to earn money.” In addition, participants noted that when the casino was established the owners promised higher wages than other employers in the county at that time. The participants explained that the local businesses encouraged the casino to change this policy because the other businesses did not want to compete with the higher pay scale. This is an example of a discriminatory pattern that seeks to keep privilege and power intact for the dominant group, in this case the decision-makers (Krieger, 1999).

The results of these factors are poor social outcomes and poor community health. The participants noted unemployment is high for African Americans. Children are dropping out of school and entering the criminal justice system for illegal activities, such as selling drugs. People with family roots are leaving the community which breaks down social capital further. The participants suggested that the lack of opportunities has diminished the social and economic resources necessary for health and contributed to heart disease, poor eating habits, teen pregnancy, depression and a general lack of hope. These findings are supported by research that suggests that people of higher socioeconomic status have access to social and economic resources (e.g., money, power, social connections) that benefit health status (Link & Phelan, 2005).

While the picture seems bleak, the participants expressed hope. Similar to other communities, the participants recognized that hope is necessary to create change (Benedict, et al., 2007). In Pemiscot County, community members expressed hopes that if the community begins to work together, they can advocate for better education for their children. They expressed hopes that resources can be shared to start small businesses. They expressed hopes that the community can create mentors for African American children and teach them the skills needed to open businesses in the future. Moreover, they expressed a hope to change policies by participating in the political process. All of these activities will help increase emotional and social support and create positive plans for the future (Bartley, 2006). Further, if the community can build vertical social capital inclusively (i.e., including African Americans in decision-making processes) instead of exclusively (i.e., leaving African Americans out of these processes) opportunities to create community change will bring the community together rather than divide the community (Lochner, Kawachi, Brennan, & Buka, 2002).

Study limitations

This study has limitations related to generalizability. A small, convenience sample was used in this study. While key informants identified participants based on their knowledge and experiences of employment in Pemiscot County, this sample does not represent the entire African American community in the area. Therefore, it cannot be assumed that the results capture all of the experiences and perceptions of the community.

External validity is used in quantitative work to determine the ability to which research findings can be generalized to other groups. The ability to generalize the findings from this study is low given quantitative criteria. In qualitative work, a strength is the recognition that context is specific. It is difficult and inappropriate to assume that the specific findings in one community would be similar to those in other communities. This limitation is real and needs to be considered. However, it has been suggested that it may be inappropriate to use the same criteria to judge qualitative work as is used to evaluate quantitative work (Lincoln & Guba, 1985).

Qualitative work seeks to understand the meaning people assign to events and relationships in their lives (Lincoln & Guba, 1985; Miles & Huberman, 1994). For this study, one limitation is that the perceptions of how the distribution of money, resources, and power affect access to employment and community health is specific to the community’s context (e.g., history, geographic location, rurality). A benefit of gathering data specific to local context is that it provides information necessary to create strategies that are locally relevant. However, there is a benefit beyond the local community, the participant’s perceptions add to the evidence that inequitable distribution of money, power, and resources affects daily living conditions and contributes to health disparities.

Implications for practice

The Sustainable Livelihoods framework brings to light the importance of community assets, policymaking and opportunities to make a living to the health and well-being of our communities. This echoes the recommendations in a recent report developed by the World Health Organization, Closing the Gap in a Generation (Commission on Social Determinants of Health, 2008). The report makes two recommendations that the work in Pemiscot County supports. First, to improve daily living, people need access to “full and fair employment” (p. 6) created through social and economic policymaking. Second, to decrease the maldistribution of power, money, and resources efforts must be made to increase opportunities for all people to participate in decision-making.

Research in Pemiscot County supports the World Health Organization’s recommendations that to improve community health and decrease health disparity, more attention must be paid to programs and policies beyond the traditional scope of health. This work also highlights the need to identify local policies and practices that construct the conditions of daily life. The participants in Pemiscot County did not identify state and federal policies that regulate access to money and resources. The participants noted their perceptions that informal local policies and practices keep money and resources concentrated within historically powerful sectors of the community. This suggests that attention not only be given to programs and policies that foster social and economic development at state or national levels but local levels as well.

Through this study, MOTM has identified two small ways to move forward. First, MOTM understands that to create programs and policies that foster social and economic development for everyone in the county, African Americans need to be part of the decision-making body. Building stronger horizontal and vertical social capital, eventually, will increase opportunities for African American leadership and representation on city council, school board, and economic development associations. With this type of participation Pemiscot County will be able to create programs and policies that account for the needs of those typically underrepresented in decision-making (e.g., African Americans, poor whites) and, thus, improve community health.

Second, to address economic development and increase employment opportunities, MOTM is developing a sustainable food system. A sustainable food system is one that builds community self reliance and promotes social justice and democratic decision-making to provide community members with a safe, culturally appropriate, and nutritional food source (Garrett & Feenstra, 1999). To achieve a sustainable food system, Men on the Move is developing community gardens, providing jobs, developing leadership skills, and increasing distribution of locally grown food. In addition, the mayor and alderpersons in two towns as well as the director of economic development for the region continue to provide support in the form of land and services to see this project through completion. Support of this nature for work in the African American community is a new milestone in Pemiscot County.

While the issues raised in this study seem overwhelming as compared to the meager resources available to support interventions, community members in Pemiscot County are passionate about creating change. The process of participating in this study has ignited opportunities to engage new partners (local government), begin to develop small scale economic development projects (e.g. sustainable food system), and engage local institutions in small ways which, hopefully, will trickle down to the individual level.

Acknowledgements

This research was made possible by grant support from the National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities (R24 MD001590. Baker, PI). The authors gratefully acknowledge the continued support of Pemiscot County Community Partners.

References

- Adler N, Stewart J, Cohen S, Cullen M, Diez Roux A, Dow W, et al. Reaching for a Healthier Life: Facts on Socioeconomic Status and Health in the U.S. The John D. and Catherine T. Macarthur Foundation Research Network on Socioeconomic Status and Health; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson LM, Scrimshaw SC, Fullilove M, Fielding JE the Task Force on Community Preventive Services. The Community Guide’s Model for Linking the Social Environment to Health. Am J Prev Med. 2003;24(3S):12–20. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00652-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker EA, Metzler M, Galae S. Addressing social determinants of health inequities: Learning from doing. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95(4):553–555. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.061812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker EA, Motton F. Creating Understanding and Action through Group Dialogue. In: Israel B, Eng E, Schulz A, Parker EA, editors. Methods in Community-Based Participatory Research. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2005. pp. 307–325. [Google Scholar]

- Bartley M, editor. Capability and resilience: Beating the odds. London: UCL Department of Epidemiology and Public Health; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Benedict S, Campbell M, Doolen A, Rivera I, Negussie T, Turner-McGrievy G. Seeds of HOPE: A model for addressing social and economic determinants of health in a women's obesity prevention project in two rural communities. Journal of Women's Health. 2007;16(8):1117–1124. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2007.CDC9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Rural Health Practice. Bridging the Health Divide: The Rural Public Health Research Agenda. Bradford, PA: University of Pittsburgh at Bradford; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers R, Conway G. Sustainable rural livelihoods: Practical concepts for the 21st century. Brighton, England: University of Sussex, Institute of Development Studies; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Final Report of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Department of International Development. Sustainable livelihoods guidance sheets. [Retrieved April 7, 2006];2007 from http://www.livelihoods.org/info/guidance_sheets_pdfs/section2.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Dooley D, Feilding J, Levi L. Health and unemployment. Annual Review of Public Health. 1996;17:449–465. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pu.17.050196.002313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrett S, Feenstra G. Growing a Community Food System. Pullman, WA: Western Rural Development Center; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Graham H. Social determinants and their unequal distribution: Clarifying policy understandings. The Milbank Quarterly. 2004;82(1):101–124. doi: 10.1111/j.0887-378X.2004.00303.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock T. People, partnerships and human progress: Building community capital. Health Promotion International. 2001;16(3):275–280. doi: 10.1093/heapro/16.3.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper D. Talking about pictures: A case for photo elicitation. Visual Studies. 2002;17(1):13–26. [Google Scholar]

- Jin R, Shah C, Svoboda T. The impact of unemployment on health: A review of the evidence. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 1995;153(5):529–540. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson J, Parnell A, Santos P, Crutchfield P. A competitive assessment of Pemiscot County, Missouri. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kawachi I, Kennedy B, Glass R. Social capital and self-rated health: A contextual analysis. American Journal of Public Health. 1999;89(8):1187–1193. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.8.1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R, House J, Turner BJ. Unemployment in a community sample. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1987;28(1):51–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger N. Embodying inequality: a review of concepts, measures, and methods of studying health consequences of discrimination. International Journal of Health Services. 1999;29(2):295–352. doi: 10.2190/M11W-VWXE-KQM9-G97Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger N. Ladders, pyramids and champagne: the iconography of health inequities. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2008a;62:1098–1104. doi: 10.1136/jech.2008.079061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger N. Proximal, distal, and the politics of causation - what's level got to do with it? American Journal of Public Health. 2008b;89:221–230. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.111278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln Y, Guba E. Naturalistic inquiry. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Link B, Phelan J. Fundamental sources of health inequalities. In: Mechanic D, Rogut L, Colby D, Knickman J, editors. Policy Challenges in Modern Health Care. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press; 2005. pp. 71–84. [Google Scholar]

- Lochner K, Kawachi I, Brennan R, Buka S. Social capital and neighborhood mortality rates in Chicago. Social Science & Medicine. 2002;56(8):1797–1805. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00177-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmot M, Wilkinson R, editors. Social determinants of health. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Martikainen PT. Unemployment and mortality among Finnish men 1981–5. British Medical Journal. 1990;301:407–411. doi: 10.1136/bmj.301.6749.407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathers C, Schofield D. The health consequences of unemployment: The evidence. MJA. 1998;168:178–182. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1998.tb126776.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles M, Huberman A. Qualitative data analysis. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Missouri Department of Health and Senior Services. Leading Cause of Death Profile for Pemiscot County Residents by Race. [Retrieved December 10, 2008];2008 from http://www.dhss.mo.gov/CommunityDataProfiles/index.html.

- Missouri Economic Research and Information Center. Regional data lower Southeast Region. [Retrieved November 28, 2006];2006 from http://www.ded.mo.gov/researchandplanning/regional/lowersoutheast/index.stm.

- Muhr R. User's Manual for ATLAS.ti 5.0, ATLAS.ti Scientific Software. Berlin: Development GmbH; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Office of Social and Economic Data Analysis. MU Extension Social and Economic Profile: Pemiscot County, MO. [Retrieved May 8, 2007];2007 from http://www.oseda.missouri.edu/ [Google Scholar]

- Pappas G, Queen S, Hadden W, Fisher G. The increasing disparity in mortality between socioeconomic groups in the United States, 1960 and 1986. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1993;329(2):103–109. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199307083290207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picket KE, Pearl M. Multilevel analyses of neighborhood socioeconomic context and health outcomes: a critical review. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2001;55:111–122. doi: 10.1136/jech.55.2.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Probst J, Samuels M, Jespersen K, Willert K, Swann RS, McDuffie JA. Minorities in Rural America: An Overview of Population Characteristics. Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Rural Health Research Center; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Roseland M. Toward sustainable communities: Resources for citizens and their governments. Stoney Creek, CT: New Society Publishers; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Scoones I. Sustainable rural livelihoods: A framework for analysis. Brighton: University of Sussex; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Smith G, Hart C, Watt G, Hole D, Hawthorne V. Individual social class, area-based deprivation, cardiovascular disease risk factors, and mortality: the Renfrew and Paisley Study. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 1998;52:399–405. doi: 10.1136/jech.52.6.399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solar O, Irwin A. A conceptual framework for action on the social determinants of health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Toldson I. Breaking Barriers: Plotting the Path to Academic Success for School-age African-American Males. Washington, DC: Congressional Black Caucus Foundation; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- United States Census Bureau. American factfinder. [Retrieved October 18, 2007];2007 from http://factfinder.census.gov.

- Williams D. Patterns and causes of disparities in health. In: Mechanic D, Rogut L, Colby D, Knickman J, editors. Policy Challenges in Modern Health Care. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press; 2005. pp. 115–134. [Google Scholar]

- Wolcott H. Writing up qualitative research. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2001. [Google Scholar]