Abstract

Objectives

We examined the association of physical activity with prospectively assessed posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms in a military cohort.

Methods

Using baseline and follow-up questionnaire data from a large prospective study of U.S. service members, we applied multivariable logistic regression to examine the adjusted odds of new-onset and persistent PTSD symptoms associated with light/moderate physical activity, vigorous physical activity, and strength training at follow-up.

Results

Of the 38,883 participants, 89.4% reported engaging in at least 30 minutes of physical activity per week. At follow-up, those who reported proportionately less physical activity were more likely to screen positive for PTSD. Vigorous physical activity had the most consistent relationship with PTSD. Those who reported at least 20 minutes of vigorous physical activity twice weekly had significantly decreased odds for new-onset (odds ratio [OR] = 0.58, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.49, 0.70) and persistent (OR=0.59, 95% CI 0.42, 0.83) PTSD symptoms.

Conclusions

Engagement in physical activity, especially vigorous activity, is significantly associated with decreased odds of PTSD symptoms among U.S. service members. While further longitudinal research is necessary, a physical activity component may be valuable to PTSD treatment and prevention programs.

Recent military operations in Iraq and Afghanistan have been characterized by sustained ground combat, persistent risk, and multiple protracted deployments. Increased psychological symptom reporting has engendered heightened concern for the postdeployment mental health of service members and, in particular, the public health burden of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).1–4 A previous study using data from all U.S. service branches identified new-onset self-reported PTSD symptoms in 7.6%–8.7% of deployers who reported combat exposures, 1.4%–2.1% of deployers who did not report combat exposures, and 2.3%–3.0% of nondeployers.4

PTSD is associated with poor physical health as well as negative health behaviors, such as tobacco use and problem alcohol drinking.5–11 The extent to which behavioral correlates of PTSD mitigate or mediate PTSD symptoms and associated morbidities is currently under investigation.12 While research has focused on adverse health behaviors, the relationship between positive health behaviors (e.g., physical activity) and PTSD has not been fully explored.

Studies of depression and anxiety have pointed to the mental health benefits of physical activity, and researchers have postulated a number of mechanisms by which physical activity may modulate mood and the stress response.13–19 While previous research indicates that physical activity may mitigate PTSD and related symptoms, other studies indicate that exercise habits of PTSD patients may be substandard.20–23 In a retrospective study among Brazilians, physical activity levels decreased after the onset of PTSD.24 These previous studies, however, were limited by small sample sizes, retrospective designs, and an inability to control for possible confounders.20,22–25 The purpose of this study was to investigate new-onset, resolution, and persistence of PTSD symptoms in relation to type and quantity of physical activity in a large, population-based cohort of U.S. military service members.

METHODS

Population and data sources

The Millennium Cohort Study was launched in 2001, before the start of the current operations in Afghanistan and Iraq, to gather and evaluate behavioral and occupational characteristics related to military service that may be associated with adverse health outcomes.26,27 The methodology of the Millennium Cohort Study has been described elsewhere in detail.27 Participants for this study were enrolled in 2001. Participants are followed every three years, regardless of military status at the time of follow-up. Of the U.S. service members invited in 2001, 77,047 (36%) completed a baseline questionnaire and consented to participate in this prospective study.

Investigations of potential biases found the Millennium Cohort to be well-representative, with participants reporting reliable data and not influenced to participate by poor health before enrollment.28–35 Invited participants were randomly selected from U.S. military personnel serving in 2000, with oversampling for women; those who deployed to Bosnia, Kosovo, or Southwest Asia (1998–2000); and Reserve and National Guard members. Of the 77,047 consenting participants, 55,021 (71%) completed the follow-up questionnaire (2004–2006).

Participants in this study included consenting members who completed baseline and follow-up questionnaires. Given that deployment experience is associated with an increased risk of PTSD and onset of symptoms may be delayed, participants with deployment experience in support of the operations in Iraq and Afghanistan prior to baseline or who completed a questionnaire while deployed were removed from analyses (n=5,333).1,2,4 Because physical activity levels may vary during pregnancy, those women who reported being pregnant, giving birth, or having a miscarriage since baseline were also excluded (n=2,765). Participants were also excluded from the study population if any of their responses for the physical activity questions did not include the number of days and minutes per day of physical activity (n=2,991) or lacked internal consistency (n=1,032). Of the remaining 42,900 eligible participants, 38,883 (90.6%) with complete data were included in this study. The participants were then stratified into two study populations according to absence (n=37,482, 96.4%) or presence (n=1,401, 3.6%) of baseline PTSD symptoms to investigate new-onset and persistent symptoms.

We obtained demographic and military-specific data from electronic personnel files and included gender, birth year, education level, marital status, race/ethnicity, deployment experience, pay grade, service component (active duty and Reserve/National Guard), service branch (Army, Air Force, Navy, Coast Guard, and Marine Corps), and occupation.

Data from the Millennium Cohort questionnaires include information regarding physical and mental health, deployment, occupational exposures, and other health outcomes and exposures. Questions on physical activity were first included in the survey instrument in 2004 (the first follow-up questionnaire) using questions modified from the 2001 National Health Interview Survey.36 Participants reported their typical weekly physical activity at follow-up by estimating the average number of minutes per day and days per week spent in each of three categories: strength training, vigorous physical activity, and moderate or light physical activity. For each category, participants were given the option to indicate “none” or “cannot physically do.” Strength training was described by the questionnaire as “strength training or work that strengthens your muscles (e.g., lifting/pushing/pulling weights).” Vigorous physical activity was described as “vigorous exercise or work that causes heavy sweating or large increases in breathing or heart rate (e.g., running, active sports, marching, biking).” Moderate or light physical activity was described as “moderate or light exercise or work that causes light sweating or slight increases in breathing or heart rate (e.g., walking, cleaning, slow jogging).”

For our primary analyses, we classified participants into one of five categories for each type of activity. Participants were placed in the highest activity category for which they met the criteria: (1) “very active,” defined as ≥20 minutes per day for ≥5 days per week; (2) “active,” defined as ≥20 minutes per day for ≥2 days per week; (3) “slightly active,” defined as a total of ≥30 minutes per week, regardless of the frequency or daily duration; (4) “inactive” if reporting a total of <30 minutes per week of activity; and (5) “cannot physically do,” if they so indicated. While this is not a standard method of categorization, we decided a priori to classify physical activity in this manner to capture any small differences that may have a positive or negative effect on the mental health of service members.

Additionally, because some service members may be disabled from injuries suffered during deployment or other reasons, we thought it was important to include and examine the participants who indicated that they were not able to perform certain types of physical activity. Because we did not use a standard method of categorization, we performed subanalyses to examine if different ways of classification altered the results. In subanalyses, we calculated each person's total minutes per week and total days per week for each category to further examine the relationship between physical activity and PTSD.

Outcomes

We assessed PTSD symptoms using the PTSD Checklist-Civilian Version (PCL-C), a 17-item self-report measure.37,38 Using a five-point Likert scale (from 1 = not at all to 5 = extremely), participants rated the severity of each intrusion, avoidance, and hyperarousal symptom during the past 30 days. We used two methods to identify those with PTSD symptoms at baseline and follow-up. The sensitive definition of PTSD symptoms used the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition (DSM-IV) criteria alone, which requires a moderate or higher level of at least one intrusion symptom, three avoidance symptoms, and two hyperarousal symptoms.39 Participants met the specific criteria if they had a total score of ≥50 on a scale from 17 to 85 points and if they met the DSM-IV criteria.1,4,37–41 Using this instrument with a cutoff of 50 has been reported to be highly specific (specificity = 99%), but with a lower sensitivity (60%).40 Among those without PTSD symptoms at baseline, we defined those who met criteria at follow-up as having new-onset symptoms. Among those with PTSD symptoms at baseline, we defined those who continued to meet criteria at follow-up as having persistent symptoms and those who no longer met criteria as having symptom resolution.

Statistical analyses

We completed descriptive and univariate analyses to compare characteristics among PTSD symptom groups as well as physical activity levels. We used multivariable logistic regression to compare the adjusted odds of new-onset and persistent PTSD symptoms by physical activity level in each activity category. We adjusted final models for other types of physical activity, demographics, military characteristics, occupation, self-reported combat exposures, prior PTSD diagnosis, body mass index (BMI), potential alcohol dependence, and tobacco use.

We performed subanalyses to examine possible effects of depression and physical health on the relationship between physical activity and PTSD. The first models controlled for baseline major depressive syndrome, measured by the Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders (PRIME-MD) Patient Health Questionnaire, and assessed using criteria from the DSM-IV.42,43 The second models controlled for the transition of physical health from baseline to follow-up, assessed by the change in the physical component summary score from the Medical Outcomes Study Short Form 36-Item Health Survey for Veterans.44–46 We performed regression diagnostics, including tests for goodness of fit and collinearity, for all models. We conducted all data analyses using SAS® version 9.1.47 We conducted this research in compliance with all applicable federal regulations governing the protection of human subjects in research (Protocol NHRC.2000.007). We obtained written consent from all participants.

RESULTS

Descriptive statistics

Of the 38,883 study participants, nearly all of them reported engaging in some physical activity, with 89.4% reporting at least 30 minutes per week of at least one type of activity. Of the 37,482 participants who screened negative for PTSD at baseline using the sensitive criteria, 1,060 (2.8%) screened positive at follow-up. Of the 1,401 participants who screened positive for PTSD at baseline, 581 (41.5%) also screened positive at follow-up (Table 1). Using the specific criteria, 780 participants had PTSD symptoms at baseline, with symptoms persisting in 336 (43.1%) of these members (data not shown). Of the 38,103 participants who did not meet the specific criteria at baseline, 658 (1.7%) had new-onset symptoms at follow-up.

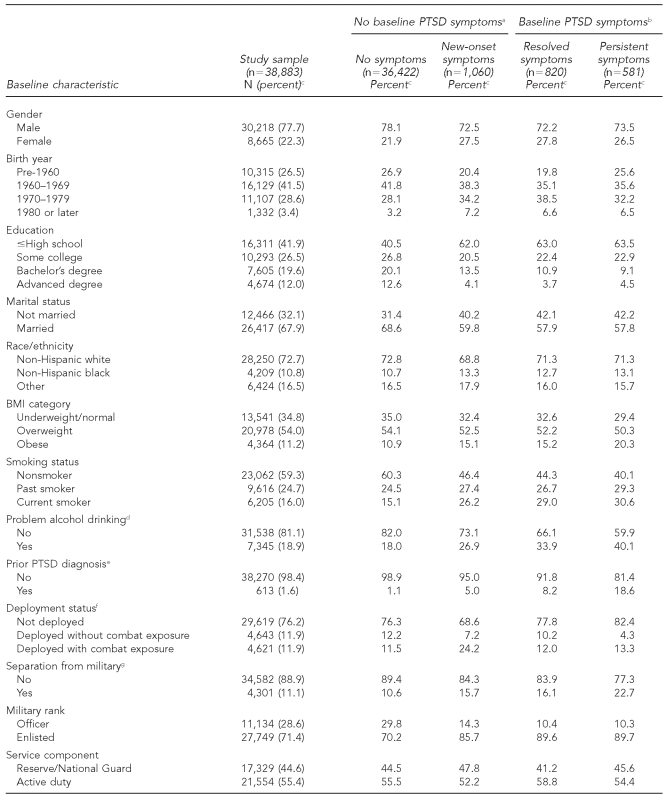

Table 1.

Characteristics of Millennium Cohort Study participants by PTSD, 2001–2006

aAll individual characteristics were independently associated with new-onset PTSD symptoms (p<0.05).

bBirth year, BMI category, problem alcohol drinking, prior PTSD diagnosis, deployment status, separation from the military, and branch of service were independently associated with persistent PTSD symptoms (p<0.05).

cPercentages may not sum to 100 due to rounding.

dAt baseline, participants endorsed at least one of the following: felt a need to cut back on drinking, felt annoyed at someone who suggested they cut back on drinking, felt a need for an eye-opener or early-morning drink, or felt guilty about their drinking.

eSelf-reported having ever being diagnosed with PTSD by a doctor or other health professional at baseline

fAt least one complete deployment in support of operations in Iraq and Afghanistan between baseline and follow-up questionnaires

gSeparated from military service before completing the follow-up questionnaire

PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder

BMI = body mass index

As displayed in Table 1, univariate analyses revealed that all characteristics were independently associated with screening positive for new-onset PTSD among participants without baseline symptoms. Notably, participants with new-onset PTSD symptoms were proportionately more likely to be female, younger, less educated, not married, current smokers, enlisted, and Army members, as well as more likely to screen positive for problem alcohol drinking, have deployed with combat exposure to the current conflicts, and have an occupation other than combat specialist, health-care specialist, or functional support compared with those who did not screen positive for PTSD. Among those with baseline PTSD symptoms, participants who screened positive for PTSD at follow-up were proportionately more likely to be older, obese, separated from the military, and Army members as well as more likely to screen positive for problem alcohol drinking, self-report a PTSD diagnosis prior to baseline, and have not deployed in support of the operations in Iraq and Afghanistan compared with those who only screened positive for PTSD at baseline.

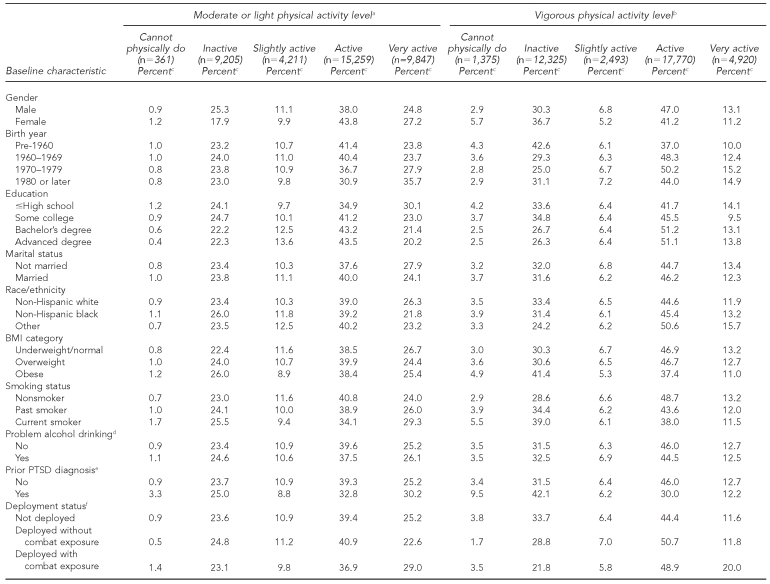

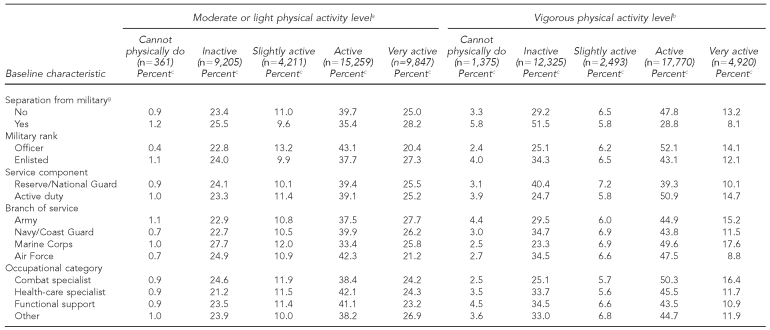

Univariate analyses exhibited that all characteristics were independently associated with moderate or light physical activity (p<0.05). Notably, those who were “active” for moderate or light physical activity were proportionately more likely to be female, older, more educated, nonsmokers, without a history of PTSD diagnosis, deployed without combat exposure, still serving in the military, and officers (Table 2). In contrast, those who were “very active” in moderate or light physical activity were proportionately more likely to be younger, less educated, non-Hispanic white, current smokers, with a prior PTSD diagnosis, deployed with combat exposure, enlisted, and serving in a branch other than the Air Force.

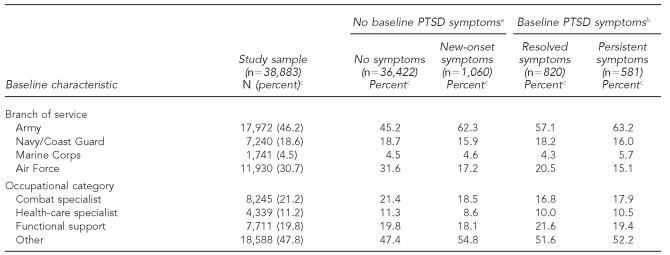

Table 2.

Characteristics of Millennium Cohort Study participants by physical activity levels, 2001–2006

aAll individual characteristics were independently associated with light or moderate activity level (p<0.05).

bAll individual characteristics, except for problem alcohol drinking (p<0.10), were independently associated with vigorous activity level (p<0.05).

cPercentages may not sum to 100 due to rounding.

dAt baseline, participants endorsed at least one of the following: felt a need to cut back on drinking, felt annoyed at someone who suggested they cut back on drinking, felt a need for an eye-opener or early-morning drink, or felt guilty about their drinking.

eSelf-reported having ever being diagnosed with PTSD by a doctor or other health professional at baseline

fAt least one complete deployment in support of operations in Iraq and Afghanistan between baseline and follow-up questionnaires

gSeparated from military service before completing the follow-up questionnaire

BMI = body mass index

PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder

With the exception of problem alcohol drinking, all characteristics were also independently associated with vigorous physical activity (p<0.05). Participants who were classified as “active” and “very active” for vigorous physical activity were similar to each other. Both these groups were proportionately more likely to be male, born in 1960 or later, neither non-Hispanic white nor black, underweight/normal or overweight, nonsmokers, without a history of PTSD diagnosis, still serving in the military, officers, serving on active duty, Marines, and combat specialists (Table 2). Those who were “active” in vigorous physical activity were also more likely to be more educated and deployers without combat exposure, while those who were “very active” were proportionately more likely to be deployers with combat exposures. All characteristics were also significantly associated with strength-training activity levels (p<0.05) and showed similar trends as with vigorous activity levels, with the exception that those who were “active” and “very active” were proportionately more likely to be nonwhite and deployers with combat exposures, while those who were “very active” were proportionately more likely to be enlisted (data not shown).

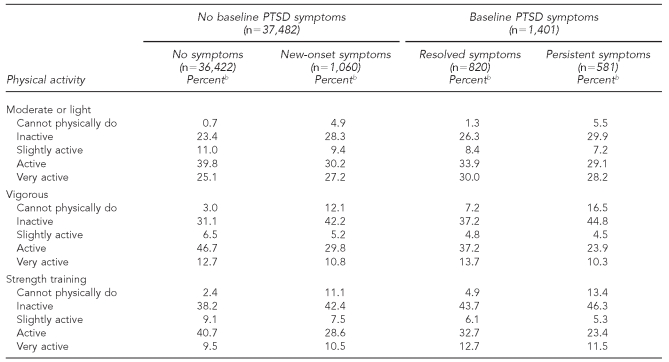

We compared the physical activity levels of those with and without PTSD symptoms at baseline and follow-up, using the sensitive criteria (Table 3). Overall, those who had symptoms at follow-up, whether they were new or persistent, were proportionately less active in all three categories of physical activity than those who did not have symptoms at follow-up. However, there was one exception: “very active” engagement in moderate or light activity and strength training was proportionately higher among those with new-onset symptoms than among those with no symptoms at either baseline or follow-up. Trends were similar when PTSD symptoms were defined according to the specific criteria (data not shown).

Table 3.

Proportion of physical activity by PTSD symptomsa among Millennium Cohort Study participants, 2001–2006

aPTSD symptoms based on the Patient Checklist-Civilian Version using the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition, criteria.

bPercentages may not sum to 100 due to rounding.

PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder

Multivariable analysis

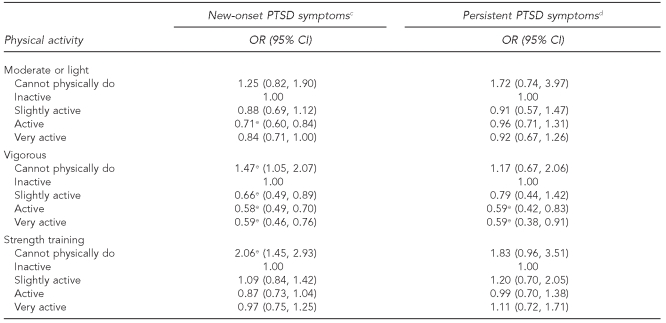

Multivariable logistic regression revealed a statistically significant association among all three types of physical activity and new-onset PTSD symptoms defined by the sensitive criteria (Table 4). Vigorous physical activity had the most consistent relationship with PTSD: participants who reported at least 30 minutes of vigorous activity per week were at significantly reduced odds of having new-onset symptoms compared with those who reported <30 minutes of physical activity per week. Specifically, those who were slightly active (odds ratio [OR] = 0.66, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.49, 0.89), active (OR=0.58, 95% CI 0.49, 0.70), and very active (OR=0.59, 95% CI 0.46, 0.76) in vigorous physical activity were at reduced odds of screening positive for new-onset PTSD. Participants who were “active” in moderate or light physical activity had reduced odds (OR=0.71, 95% CI 0.60, 0.84) of new-onset PTSD compared with those who reported <30 minutes per week. Indicating “cannot physically do” for either vigorous physical activity (OR=1.47, 95% CI 1.05, 2.07) or strength training (OR=2.06, 95% CI 1.45, 2.93) was associated with elevated odds of new-onset PTSD.

Table 4.

Adjusted oddsa of new-onset and persistent PTSD symptomsb by physical activity level among Millennium Cohort Study participants, 2001–2006

aAdjusted for all physical activity variables, gender, birth year, education, marital status, race/ethnicity, body mass index, smoking status, problem alcohol drinking, prior PTSD diagnosis, deployment status, separation from military, military rank, service component, branch of service, and occupation.

bPTSD symptoms are based on the Patient Checklist-Civilian Version using the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition, criteria.

cThose with new-onset PTSD symptoms were compared with those with no PTSD symptoms.

dThose with persistent PTSD symptoms were compared with those with resolved PTSD symptoms.

ep<0.05

PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder

OR = odds ratio

CI = confidence interval

The ORs for each category among the three types of physical activity in the persistent symptoms models exhibited the same direction of association, with the exception of “very active” for strength training. In general, the estimates were weaker and not as precise for the persistent models (Table 4). Specifically, only those who were “active” (OR=0.59, 95% CI 0.42, 0.83) or “very active” (OR=0.59, 95% CI 0.38, 0.91) for vigorous activity had significantly reduced odds of persistent PTSD symptoms. In the subanalyses, neither baseline depression symptoms nor the change in physical health significantly changed the relationship between PTSD symptoms and physical activity.

When we defined PTSD symptoms according to the specific criteria, results exhibited only minor differences (data not shown). Most notably, the association between strength training and new-onset symptoms was no longer statistically significant. The relationship of moderate or light and vigorous physical activity with PTSD symptoms did not depend on the criteria used, although small fluctuations in significance levels were observed.

To assess the sensitivity of model parameters to the chosen physical activity metric, logistic regression models were fitted using two alternate measures of physical activity (data not shown). When physical activity was measured using total minutes per week, results were similar to the original models. Modest volumes (<120 minutes per week) of moderate or light physical activity and any amount of vigorous physical activity were associated with reduced odds of new-onset symptoms as measured by the sensitive criteria. Engaging in vigorous activity 120–300 minutes per week was associated with reduced odds of persistent PTSD symptoms. Physical activity measured by number of days of activity per week exhibited a similar relationship with new-onset and persistent symptoms as the main analyses.

DISCUSSION

Using prospective data from the Millennium Cohort, this study found a statistically significant inverse association between prospectively assessed PTSD symptoms and physical activity measured at follow-up, after controlling for smoking history, problem alcohol drinking, and other possible confounders. Furthermore, this association persisted after controlling for baseline depression symptoms and changes in physical health. The most consistent trend from the multivariable models was the association of vigorous physical activity with decreased odds of both new-onset and persistent PTSD symptoms. There appeared to be a threshold effect, such that increased participation above “slightly active” did not lead to a further reduction in the odds of PTSD symptoms. The associations of light or moderate physical activity and strength training with new-onset PTSD symptoms exhibited a similar, but weaker, pattern.

While the relationship between light or moderate physical activity and strength training with persistent PTSD symptoms was not statistically significant, the power to detect such an association may have been limited by the small number of participants who met PTSD criteria at both baseline and follow-up within each activity level. There was also an association between those who reported they were physically unable to do physical activity and PTSD. While only two of the associations were statistically significant, those who reported they were physically unable to do physical activity had increased odds of PTSD for both new-onset and persistent PTSD symptoms in each activity type relative to those who were inactive.

Consisting of a large cohort of U.S. military service members, the study population's larger sample size (n=38,883) permitted control for many possible confounders, including smoking status, potential alcohol dependence, BMI, and prior PTSD diagnosis. This was the first study to examine the relationship between physical activity and prospectively assessed PTSD by identifying and stratifying participants according to baseline symptomology. Furthermore, this study considered a more complex relationship between PTSD symptoms and physical activity by using more refined measures of physical activity: three types of physical activity (light or moderate, vigorous, and strength training) and various activity levels (ranging from “cannot physically do” to “very active”) within each category.

Overall, U.S. service members are younger and healthier than the U.S. general population and, due to occupational requirements, may be more likely to be physically active.48,49 Each branch of the service has established physical fitness tests to ensure readiness to fight. Those who fail the fitness test are administratively managed to improve fitness levels, and those who fail to do so, without an accompanying medical limitation, may be administratively separated from service. The results of this study provide further incentive to strongly enforce these established physical fitness requirements and may possibly suggest that participation in physical activities among service members may be beneficial to prevent and/or treat PTSD. Because researchers have postulated a number of mechanisms by which physical activity may modulate mood and the stress response, it is possible that participating in physical activity may act in some manner to prevent the development of PTSD among those exposed to a traumatic event, as well as alleviate PTSD symptoms among those already diagnosed.14,15

While more research is needed, the associations noted in this article may have implications for further research on the prevention and/or treatment of PTSD, a common condition seen in military veterans.50 Because PTSD tends to be chronic and frequently requires ongoing treatment, additional effective therapies are needed. The lower odds of persistent PTSD symptoms associated with physical activity support further investigation into whether it may have utility as a PTSD treatment.

In this study, the disability status of participants who reported they were physically unable to do an activity was not determined. Due to the nature of the questionnaire, we were unable to distinguish between being unable to perform physical activity due to a permanent disability or due to a temporary condition, such as a broken leg or illness. Regardless of the reason, this study indicates that service members who are unable to perform physical activities are at increased odds of screening positive for PTSD. It may be that these service members are more likely to be injured while deployed, which independently increases the risk of PTSD.51

Limitations and strengths

Despite the longitudinal assessment of PTSD symptoms in this study, the interpretation of the findings from this study was limited by the fact that physical activity levels were measured only at follow-up. Specifically, it was not possible to determine whether physical activity was a precursor or a consequence of PTSD symptoms. Findings from previous studies suggest that both may be true.20,22,24 Additional prospective observational and interventional studies are essential to determine the temporal relationship of physical activity with PTSD. As data collection for the Millennium Cohort study continues, it will become feasible to assess both physical activity and PTSD symptoms longitudinally.

Additionally, the PCL-C was used to assess PTSD symptoms and, while it is a standardized and validated instrument, it is a surrogate for a clinical diagnosis and may misclassify PTSD status. Self-reported physical activity was used in this study and may over- or underrepresent actual physical activity levels.52,53 However, studies using a variety of survey instruments have found self-report of physical activity to be generally valid and reliable.54–56 Frequency and duration of both recreational and occupational physical activities were asked in a single question; activity that is performed as part of one's occupation may be much longer in duration than recreational activities. In a military setting, though, it may be difficult to differentiate between recreational and occupational physical activity, so grouping the two types may be appropriate for this population. Furthermore, because physical activity was categorized into levels, extremely long durations of performing certain activities would not overly influence the results. Finally, because moderate and light activities were combined into a single question, we were unable to analyze the relationship between PTSD and each of these activities separately.

This study also had a number of important strengths. This was the first study to analyze the relationship between physical activity levels and prospectively assessed PTSD symptoms in a large, population-based military cohort. Because many individuals with PTSD symptoms may not seek treatment, the PCL-C survey may more thoroughly and completely capture those with PTSD symptoms than clinical diagnosis or hospitalization data.1 Strengths of the questionnaire included the ability to quantify both frequency and duration of three types of physical activity, and to distinguish inactivity due to physical capacity from inactivity by choice. Investigation of potential biases in the Millennium Cohort has found the Cohort to be representative of the general military, to report data reliably, and to participate regardless of prior health status.27–35,49,57

CONCLUSIONS

This study provides information regarding the physical activity levels of a large, population-based military cohort, including all branches of service and Reserve/Guard members. Nearly 90% of the cohort participated in some level of physical activity on a weekly basis, which is indicative of a healthy population. This investigation demonstrates that physical activity measured at follow-up, after controlling for baseline depression, smoking history, problem alcohol drinking, and other possible confounders, is associated with decreased odds of PTSD symptoms. This finding suggests a potential for further investigation into whether increasing and structuring physical activity levels among service members, especially those preparing for or returning from deployment, mitigates PTSD symptoms. Randomized trials may aid in understanding whether physical activity is effective for the treatment and/or prevention of PTSD and will provide better guidance to military service members and veterans.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Scott L. Seggerman from the Management Information Division, U.S. Defense Manpower Data Center, Seaside, California; Michelle LeWark from NHRC; and all the professionals from the U.S. Army Medical Research and Materiel Command, especially those from the Military Operational Medicine Research Program, Fort Detrick, Maryland. Finally, the authors appreciate the support of the Henry M. Jackson Foundation for the Advancement of Military Medicine, Rockville, Maryland.

Footnotes

In addition to the authors, the Millennium Cohort Study Team includes Gina Creaven, James Davies, Lacy Farnell, Nisara Granado, Gia Gumbs, Isabel Jacobson, Travis Leleu, Jamie McGrew, Katherine Snell, Steven Speigel, Kari Sausedo, Martin White, James Whitmer, and Charlene Wong, from the Department of Deployment Health Research, Naval Health Research Center (NHRC), San Diego, California; Paul Amoroso, from the Madigan Army Medical Center, Tacoma, Washington; Gary Gackstetter, from the Department of Preventive Medicine and Biometrics, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences (USUHS), Bethesda, Maryland, and the Analytic Services, Arlington, Virginia; Gregory Gray, from the College of Public Health, University of Iowa, Iowa City, Iowa; Tomoko Hooper, from the Department of Preventive Medicine and Biometrics, USUHS; James Riddle, from the U.S. Air Force Research Laboratory, Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, Ohio; and Margaret Ryan, from the Naval Hospital, Camp Pendleton, California.

This study represents NHRC report 09-07, supported by the U.S. Department of Defense, under work unit no. 60002. This article is based upon work supported in part by the Office of Research and Development Cooperative Studies Program, Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). VA Pugent Sound provided support for Drs. Littman's and Boyko's participation in this research.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of the U.S. Department of the Navy, U.S. Department of the Army, U.S. Department of the Air Force, U.S. Department of Defense, U.S. Department of VA, nor the U.S. government. The funding organization (Military Operational Medicine Research Program and Office of Research and Development Cooperative Studies Program, Department of Veterans Affairs) had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, analysis, or preparation of data; or preparation, review, or approval of the article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hoge CW, Castro CA, Messer SC, McGurk D, Cotting DI, Koffman RL. Combat duty in Iraq and Afghanistan, mental health problems, and barriers to care. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:13–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoge CW, Auchterlonie JL, Milliken CS. Mental health problems, use of mental health services, and attrition from military service after returning from deployment to Iraq or Afghanistan. JAMA. 2006;295:1023–32. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.9.1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Milliken CS, Auchterlonie JL, Hoge CW. Longitudinal assessment of mental health problems among active and reserve component soldiers returning from the Iraq war. JAMA. 2007;298:2141–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.18.2141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith TC, Ryan MA, Wingard DL, Slymen DJ, Sallis JF, Kritz-Silverstein D. New onset and persistent symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder self reported after deployment and combat exposures: prospective population based US military cohort study. BMJ. 2008;336:366–71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39430.638241.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beckham JC, Moore SD, Feldman ME, Hertzberg MA, Kirby AC, Fairbank JA. Health status, somatization, and severity of posttraumatic stress disorder in Vietnam combat veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155:1565–9. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.11.1565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jamil H, Nassar-McMillan SC, Salman WA, Tahar M, Jamil LH. Iraqi Gulf War veteran refugees in the U.S.: PTSD and physical symptoms. Soc Work Health Care. 2006;43:85–98. doi: 10.1300/J010v43n04_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wagner AW, Wolfe J, Rotnitsky A, Proctor SP, Erickson DJ. An investigation of the impact of posttraumatic stress disorder on physical health. J Trauma Stress. 2000;13:41–55. doi: 10.1023/A:1007716813407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barrett DH, Doebbeling CC, Schwartz DA, Voelker MD, Falter KH, Woolson RF, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder and self-reported physical health status among U.S. military personnel serving during the Gulf War period: a population-based study. Psychosomatics. 2002;43:195–205. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.43.3.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoge CW, Terhakopian A, Castro CA, Messer SC, Engel CC. Association of posttraumatic stress disorder with somatic symptoms, health care visits, and absenteeism among Iraq war veterans. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:150–3. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.1.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fu SS, McFall M, Saxon AJ, Beckham JC, Carmody TP, Baker DG, et al. Post-traumatic stress disorder and smoking: a systematic review. Nicotine Tob Res. 2007;9:1071–84. doi: 10.1080/14622200701488418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shipherd JC, Stafford J, Tanner LR. Predicting alcohol and drug abuse in Persian Gulf War veterans: what role do PTSD symptoms play? Addict Behav. 2005;30:595–9. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schnurr PP, Spiro A., 3rd Combat exposure, posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms, and health behaviors as predictors of self-reported physical health in older veterans. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1999;187:353–9. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199906000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Farmer ME, Locke BZ, Moscicki EK, Dannenberg AL, Larson DB, Radloff LS. Physical activity and depressive symptoms: the NHANES I Epidemiologic Follow-up Study. Am J Epidemiol. 1988;128:1340–51. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Acevedo EO, Ekkekakis P. Psychobiology of physical activity. Champaign (IL): Human Kinetics; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paluska SA, Schwenk TL. Physical activity and mental health: current concepts. Sports Med. 2000;29:167–80. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200029030-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dunn AL, Trivedi MH, O'Neal HA. Physical activity dose-response effects on outcomes of depression and anxiety. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001;33(6 Suppl):S587–97. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200106001-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dimeo F, Bauer M, Varahram I, Proest G, Halter U. Benefits from aerobic exercise in patients with major depression: a pilot study. Br J Sports Med. 2001;35:114–7. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.35.2.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stewart AL, Hays RD, Wells KB, Rogers WH, Spritzer KL, Greenfield S. Long-term functioning and well-being outcomes associated with physical activity and exercise in patients with chronic conditions in the Medical Outcomes Study. J Clin Epidemiol. 1994;47:719–30. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(94)90169-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Petruzzello SJ, Landers DM, Hatfield BD, Kubitz KA, Salazar W. A meta-analysis on the anxiety-reducing effects of acute and chronic exercise Outcomes and mechanisms. Sports Med. 1991;11:143–82. doi: 10.2165/00007256-199111030-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Manger TA, Motta RW. The impact of an exercise program on posttraumatic stress disorder, anxiety, and depression. Int J Emerg Ment Health. 2005;7:49–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Buckley TC, Mozley SL, Bedard MA, Dewulf AC, Greif J. Preventive health behaviors, health-risk behaviors, physical morbidity, and health-related role functioning impairment in veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder. Mil Med. 2004;169:536–40. doi: 10.7205/milmed.169.7.536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Newman CL, Motta RW. The effects of aerobic exercise on childhood PTSD, anxiety, and depression. Int J Emerg Ment Health. 2007;9:133–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Otter L, Currie J. A long time getting home: Vietnam veterans' experiences in a community exercise rehabilitation programme. Disabil Rehabil. 2004;26:27–34. doi: 10.1080/09638280410001645067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Assis MA, de Mello MF, Scorza FA, Cadrobbi MP, Schooedl AF, da Silva SG, et al. Evaluation of physical activity habits in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder. Clinics. 2008;63:473–8. doi: 10.1590/S1807-59322008000400010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Diaz AB, Motta R. The effects of an aerobic exercise program on posttraumatic stress disorder symptom severity in adolescents. Int J Emerg Ment Health. 2008;10:49–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gray GC, Chesbrough KB, Ryan MA, Amoroso P, Boyko EJ, Gackstetter GD, et al. The Millennium Cohort Study: a 21-year prospective cohort study of 140,000 military personnel. Mil Med. 2002;167:483–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ryan MA, Smith TC, Smith B, Amoroso P, Boyko EJ, Gray GC, et al. Millennium Cohort: enrollment begins a 21-year contribution to understanding the impact of military service. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60:181–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.LeardMann CA, Smith B, Smith TC, Wells TS, Ryan MA. Smallpox vaccination: comparison of self-reported and electronic vaccine records in the Millennium Cohort Study. Hum Vaccin. 2007;3:245–51. doi: 10.4161/hv.4589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith B, Smith TC, Gray GC, Ryan MA. When epidemiology meets the Internet: Web-based surveys in the Millennium Cohort Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;166:1345–54. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Riddle JR, Smith TC, Smith B, Corbeil TE, Engel CC, Wells TS, et al. Millennium Cohort: the 2001–2003 baseline prevalence of mental disorders in the U.S military. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60:192–201. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smith B, Leard CA, Smith TC, Reed RJ, Ryan MA. Anthrax vaccination in the Millennium Cohort: validation and measures of health. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32:347–53. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith B, Wingard DL, Ryan MA, Macera CA, Patterson TL, Slymen DJ. U.S. military deployment during 2001–2006: comparison of subjective and objective data sources in a large prospective health study. Ann Epidemiol. 2007;17:976–82. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2007.07.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith TC, Jacobson IG, Smith B, Hooper TI, Ryan MA. The occupational role of women in military service: validation of occupation and prevalence of exposures in the Millennium Cohort Study. Int J Environ Health Res. 2007;17:271–84. doi: 10.1080/09603120701372243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smith TC, Smith B, Jacobson IG, Corbeil TE, Ryan MA. Reliability of standard health assessment instruments in a large, population-based cohort study. Ann Epidemiol. 2007;17:525–32. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2006.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wells TS, Jacobson IG, Smith TC, Spooner CN, Smith B, Reed RJ, et al. Prior health care utilization as a potential determinant of enrollment in a 21-year prospective study, the Millennium Cohort Study. Eur J Epidemiol. 2008;23:79–87. doi: 10.1007/s10654-007-9216-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lucas JW, Schiller JS, Benson V. Summary health statistics for U.S. adults: National Health Interview Survey, 2001. Vital Health Stat. 2004;10(218) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weathers FW, Litz BT, Herman DS, Huska JA, Keane TM. The PTSD Checklist (PCL): reliability, validity, and diagnostic utility; Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies; 1993 Oct 24–27; San Antonio, Texas. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Blanchard EB, Jones-Alexander J, Buckley TC, Forneris CA. Psychometric properties of the PTSD Checklist (PCL) Behav Res Ther. 1996;34:669–73. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(96)00033-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brewin CR. Systematic review of screening instruments for adults at risk of PTSD. J Trauma Stress. 2005;18:53–62. doi: 10.1002/jts.20007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wright KM, Huffman AH, Adler AB, Castro CA. Psychological screening program overview. Mil Med. 2002;167:853–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Kroenke K, Linzer M, deGruy FV, 3rd, Hahn SR, et al. Utility of a new procedure for diagnosing mental disorders in primary care The PRIME-MD 1000 study. JAMA. 1994;272:1749–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kazis LE, Lee A, Spiro A, III, Rogers W, Ren XS, Miller DR, et al. Measurement comparisons of the medical outcomes study and veterans SF-36 health survey. Health Care Financ Rev. 2004;25:43–58. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kazis LE, Miller DR, Clark JA, Skinner KM, Lee A, Ren XS, et al. Improving the response choices on the veterans SF-36 health survey role functioning scales: results from the Veterans Health Study. J Ambul Care Manage. 2004;27:263–80. doi: 10.1097/00004479-200407000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kazis LE, Miller DR, Skinner KM, Lee A, Ren XS, Clark JA, et al. Patient-reported measures of health: The Veterans Health Study. J Ambul Care Manage. 2004;27:70–83. doi: 10.1097/00004479-200401000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.SAS Institute, Inc. SAS®/STAT®: Version 9.1. Cary (NC): SAS Institute, Inc.; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Krueger GP, Banderet LE. Implications for studying team cognition and team performance in network-centric warfare paradigms. Aviat Space Environ Med. 2007;78(Suppl 5):B58–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Smith TC, Zamorski M, Smith B, Riddle JR, LeardMann CA, Wells TS, et al. The physical and mental health of a large military cohort: baseline functional health status of the Millennium Cohort. BMC Public Health. 2007;7:340. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Eisen SA, Griffith KH, Xian H, Scherrer JF, Fischer ID, Chantarujikapong S, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of psychiatric disorders in 8,169 male Vietnam War era veterans. Mil Med. 2004;169:896–902. doi: 10.7205/milmed.169.11.896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Grieger TA, Cozza SJ, Ursano RJ, Hoge C, Martinez PE, Engel CC, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder and depression in battle-injured soldiers. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:1777–83. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.10.1777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Klesges RC, Eck LH, Mellon MW, Fulliton W, Somes GW, Hanson CL. The accuracy of self-reports of physical activity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1990;22:690–7. doi: 10.1249/00005768-199010000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Adams SA, Matthews CE, Ebbeling CB, Moore CG, Cunningham JE, Fulton J, et al. The effect of social desirability and social approval on self-reports of physical activity [published erratum appears in Am J Epidemiol 2005;161:899] Am J Epidemiol. 2005;161:389–98. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gionet NJ, Godin G. Self-reported exercise behavior of employees: a validity study. J Occup Med. 1989;31:969–73. doi: 10.1097/00043764-198912000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kurtze N, Rangul V, Hustvedt BE, Flanders WD. Reliability and validity of self-reported physical activity in the Nord-Trondelag Health Study (HUNT 2) Eur J Epidemiol. 2007;22:379–87. doi: 10.1007/s10654-007-9110-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Norman A, Bellocco R, Bergstrom A, Wolk A. Validity and reproducibility of self-reported total physical activity—differences by relative weight. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2001;25:682–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chretien JP, Chu LK, Smith TC, Smith B, Ryan MA. Demographic and occupational predictors of early response to a mailed invitation to enroll in a longitudinal health study. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2007;7:6. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-7-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]