Abstract

Previously, we have shown that acute alcohol (EtOH) intoxication before burn injury potentiates the suppression of mesenteric lymph node T-cell effector responses. Moreover, the suppression in T-cell was accompanied with a decrease in p-38 and extracellular-signal-regulated kinase (ERK) activation. This study examined the role of protein tyrosine phosphatases (PTP) in suppressed T-cell p-38, ERK, and cytokine production after EtOH intoxication and burn injury. A blood EtOH level of ~100 mg/dl in male rats (~250 g) was achieved by gavaging animals with 5 ml of 20% EtOH suspension 4 hours before burn or sham injury (~12.5% or 25% total body surface area [TBSA]). One day after injury, rats were killed and mesenteric lymph node T-cell cytokine (IL-2/IFN-γ) production, p-38, and ERK activation were measured. As compared with shams, there was a significant decrease in T-cell cytokine production after 25% and not 12.5% TBSA burn injury. However, T-cell IL-2/IFN-γ levels were significantly decreased in rats receiving a combined insult of EtOH and burn injury regardless of the percentage of burn area. Furthermore, we found a significant decrease in p-38 and ERK-1/2 phosphorylation in T-cells of rats receiving a combined insult of EtOH and 12.5% TBSA burn compared with shams. Treatment of cells with PTP inhibitor pervanadate (10 μM) prevented T-cell p-38/ERK suppression. The suppression in IL-2/IFN-γ production was also attenuated in T-cells cultured in the presence of pervanadate. These findings suggest that an increase in PTP activity may contribute to T-cell suppression after EtOH intoxication and burn injury.

Several lines of evidence indicate an association between acute alcohol (EtOH) intoxication and trauma.1–6 Furthermore, studies have also indicated that EtOH intoxication potentiates the risk of infectious complications in trauma and burn patients.1–5 Additional findings from our laboratory and others have demonstrated that EtOH intoxication before burn injury exacerbates the suppression of intestinal T-cell function and increases gut bacterial translocation.1,7–9 Intestine-derived bacteria and their products are implicated in multiple organ dysfunction in injured patients as well as in patients with a history of EtOH exposure.1,10,11

The mechanism by which a combined insult of EtOH intoxication and burn injury influences T-cell function remains to be established. Previous studies have shown that T-cell activation precedes a cascade of signaling events and that under healthy conditions there is a dynamic equilibrium between protein kinases (PK) and protein phosphatases (PP).12–16 In a recent study, we found that this balance between phosphatases and kinases is lost in T-cell after EtOH intoxication and burn injury.17 Our findings also indicated that EtOH intoxication combined with burn injury up-regulates PP1α and suppresses the activation of p-38 and extracellular-signal-regulated kinase (ERK) after a combined insult of EtOH and burn injury.17 PP1α is a serine/threonine-specific phosphatase and we found that inhibition of PP1α with specific pharmacological agents, calyculin A and okadaic acid, prevents the p-38 and ERK suppression in T-cell after EtOH intoxication and burn injury.17 But p-38 and ERK-1/2 besides threonine also phosphorylate on tyrosine residues and it remains unclear whether protein tyrosine phosphatase (PTP) plays any role in the regulation of p-38 and ERK after EtOH intoxication and burn injury.18,19 In this study, we examined if the decrease in p-38 and ERK-1/2 activation (ie, phosphorylation) after EtOH intoxication and burn injury is due to an increase in PTP activation. To determine this, we treated isolated T-cells with PTP inhibitor pervanadate before their stimulation with anti-CD3 or Concanavalin A (Con A) and the effects of pervanadate were examined on T-cell p-38/ERK phosphorylation and cytokine (IL-2 and IFN-γ) production.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and Reagents

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (225–250 g) were purchased from Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA. Nylon wool was obtained from Polysciences, Inc., Warrington, PA. Reagents for cell culture were obtained from Fisher Scientific, Atlanta, GA. Anti-rat-CD3 antibodies were purchased from Pharmingen, San Diego, CA. Con A was obtained from Sigma, St. Louis, MO. Antibodies to p-38 protein (cat. 9712), phospho-p38 (Thr180/Tyr182, cat. 9211), ERK-1/2 protein (cat. 9102,), and phospho-ERK-1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204, cat. 9101) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology Inc., Beverly, MA. Other secondary antibodies were also obtained from Cell Signaling Technology Inc. Reagents for the sodium dodecyl sulphate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis were purchased from BioRad, Richmond, CA. Immobilon P membrane (polyvinylidine fluoride) was obtained from Millipore, Bedford, MA. Protein molecular weight markers were obtained from Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kits for IL-2 measurement was obtained from Biosource International, Camarillo, CA and for IFN-γ from R&D Systems Inc., Minneapolis, MN.

Rat Model of Acute EtOH Intoxication and Burn Injury

Rats were randomly divided into four groups: saline + sham, EtOH + sham, saline + burn, and EtOH + burn. In EtOH treated groups, rats were gavaged with 5 ml of 20% EtOH in saline. In saline groups, animals were gavaged with 5 ml of saline. At 4 hours after gavaging, a time when blood EtOH levels in EtOH-treated groups are in the range of 90 to 100 mg/dl7; rats were anesthetized and transferred into a template, which was fabricated to expose ~12.5% of the total body surface. Animals were then immersed in water bath (95–97°C) for ~10 to 12 seconds. This procedure resulted in third-degree full thickness burn injury.7 Sham-injured rats were subjected to identical anesthesia and were immersed in lukewarm water. For producing a 25% total body surface area (TBSA) injury, rats received burn or sham injury on both sides of their dorsum. It is to be noted that the burn procedure used in this study is similar to that described in our previous studies except some modification in surface area calculations. In this study, we followed the instructions described in the article of Walker and Mason (1968) and have used the formula (A = kW2/3), where k was equal to 10.20 In contrast, our previous studies have used k = 4.84 based on other published studies.21 The reason for using k = 10 is because several studies indicated this to be a more precise and accurate in surface area calculations.20 So from now onwards, we will designate the TBSA burn as 12.5%. The animals were dried immediately and given fluid resuscitation intraperitoneally with 10 ml physiological saline. Animals were allowed to recover from anesthesia, returned to their cages and were allowed food and water ad libitum.

T-Cell Preparation

One day after injury, rats were anesthetized, and via midline incision intestine was exposed. Mesenteric lymph node (MLN) were removed aseptically and processed for a single cell suspension in Hanks balanced salt solution (HBSS; Fisher Scientific) supplemented with 10 mM 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES), 50 μg/ml gentamicin, 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. The cell suspension was then loaded on to the nylon wool packed columns. These columns were preequilibrated with HBSS containing 10 mM HEPES, 50 μg/ml gentamicin, 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 5% fetal calf serum. The columns containing cells were incubated at 37°C for 50 to 60 minutes. T-cells were obtained by eluting the columns with 15 ml HBSS at a flow rate of 1 drop per second.7,22,23 T-cells thus obtained were found to be ~95% positive for anti-CD3.24

T-Cell Stimulation and Lysate Preparation

Nylon wool purified T-cells were either unstimulated or stimulated with anti-CD3 (1 μg/ml) or Con A (5 μg/ml) in the presence of various concentrations of pervanadate (sodium orthovanadate) for 5 minutes.7,22,23 Cells were lysed in a lysis buffer containing 50 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, 100 mM NaF, 1 mM MgCl2, 10 mM Na4P2O7, 200 μM Na3VO4, 0.5% Triton X-100, and 10% glycerol on ice for 45 minutes to 1 hour. Lysates were centrifuged; supernatants were harvested and stored at −70°C until analysis.

p-38 and ERK-1/2 Phosphorylation and Protein Levels

As described previously17 equal amounts of protein from each lysate preparation were analyzed on sodium dodecyl sulphate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to immobilon membranes using a semidry Trans-Blot system (Bio-RAD). The membranes were saturated with blocking buffer (10 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 0.05% Tween 20 supplemented with 5% dry milk) for 2 hours at room temperature and incubated with the desired primary antibody (1:1000 dilution) at 4°C overnight. The membranes were washed with tris buffered saline supplemented with 0.05% Tween-20 (TBST) and incubated with an appropriate secondary antibody conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (1:2000 dilution) for 1 hour at room temperature. The membranes were washed with TBST, probed using enhanced chemiluminescence dye, and phosphoproteins were autoradiographed.22,23 To measure the protein levels, membranes were reprobed for the desired protein after stripping the antibodies. The stripping was done by incubating membranes in a Western Blot Stripping Buffer (Pierce, Rockford, IL) for 30 minutes at room temperature. After this the membranes were washed with TBST and immunoblotted with specific antibodies.22,23

Measurement of T-Cell Cytokines

For cytokine measurement, T-cells were resuspended at a density of 5 × 106 cells/ml in RPMI-1640 culture medium supplemented with 2 mM L-glutamine, 10 mM HEPES, 50 μg/ml gentamicin, 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 10% fetal calf serum.7,22,23 One hundred microliters of T-cell suspension was cultured in a 96-well plate at 37°C and 5% CO2 with anti-CD3 (wells precoated with 200 μl of 2 μg/ml anti-CD3 suspension) or Con A (5 μg/ml) in the presence or absence of pervanadate. After 48 hours of culture, supernatants were harvested and IL-2 and IFN-γ levels in the supernatants were examined using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kits according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Statistical Analysis

The data, wherever applicable, are presented as means ± SEM and were analyzed using analysis of variance statistical program (Statistical Package for Social Sciences Software Program, version 2.0; Sigma Stat, Chicago, IL). A P < 0.05 between groups was considered statistically significant.

The experiments described here were performed in adherence to the National Institutes of Health Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and are approved by Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL.

RESULTS

T-Cell Cytokine Production

There was no difference in T-cell IL-2 and IFN-γ production in sham-injured rats gavaged with saline or EtOH (Figure 1). T-cell IL-2 and IFN-γ production was also not significantly different in rats receiving 12.5% TBSA burn injury alone in the absence of EtOH intoxication compared with shams. However, their levels were significantly decreased in rats receiving 25% TBSA burn injury compared with shams (Figure 1). Furthermore, IL-2 levels were significantly lower in rats receiving 25% TBSA burn compared with rats with 12.5% burn in the absence of EtOH intoxication. T-cell IL-2 and IFN-γ levels were further significantly reduced in rats receiving a combined insult of EtOH intoxication and burn injury regardless of the percent body surface burn area (Figure 1). The results indicate a greater suppression of IL-2 production by cells from rats receiving 25% TBSA burn with prior EtOH exposure compared with rats receiving either 25% TBSA burn alone or 12.5% TBSA burn regardless of EtOH exposure. However, IFN-γ levels remained almost similar in both 12.5% and 25% TBSA burn groups. The potential cause for differential effects of burn size on IL-2 and IFN-γ remains to be established. One possible explanation for this difference could be the time after injury. Our study was performed within the first 24 hours after injury and it is possible that changes in IFN-γ levels may require more time and thus appear at later time points. Together, these results indicate that burn injury size may influence MLN T-cell IL-2 and IFN-γ production and that EtOH intoxication at the time of injury further exacerbates these responses.

Figure 1.

Mesenteric lymph node (MLN) T-cells interleukin (IL)-2 (Panel A) and interferon (IFN)- γ (Panel B) production after acute alcohol (EtOH) intoxication and burn injury. MLN T-cells (5 × 106 cells/ml) were cultured with anti-CD3 (wells precoated with 2 μg/ml) in a 96-well plate at 37°C and 5% CO2. After 48 hours of culture, supernatants were harvested for the measurement of IL-2 and IFN-γ. Values are means ± SEM from at least five animals in each group. *P < 0.05 vs sham; @P < 0.05 vs 12.5% TBSA burn; #P < 0.05 vs corresponding saline + burn.

The subsequent experiments were performed using ~12.5% TBSA burn injury and the groups that were included in these experiments are saline plus sham and EtOH plus burn. We did not include EtOH alone and burn alone groups because these groups did not show significant differences from saline plus sham.

Effect of Pervanadate on T-Cell p-38 and ERK-1/2 Phosphorylation

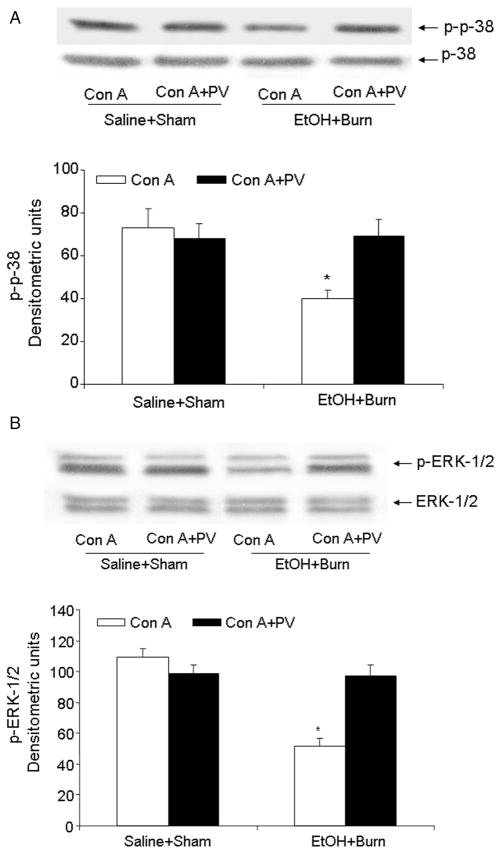

In a previous study,17 we found that on day 1 after EtOH intoxication or burn injury there was no significant change in T-cell p-38 and ERK phosphorylation compared with T-cells from sham animals. However, a significant decrease in p-38 and ERK phosphorylation was observed in T-cells obtained from rats subjected to a combined insult of EtOH intoxication and burn injury.17 In this study, we examined whether the suppression in p-38 and ERK phosphorylation after a combined insult of EtOH intoxication and burn injury is due to an increase in PTP. To test this, T-cells harvested from sham and EtOH plus burn-injured rats were treated with PTP inhibitor pervanadate (10 μM) before their stimulation with anti-CD3 antibodies and the results from this experiment are summarized in Figure 2. Results indicate that there was a significant decrease in T-cell p-38 and ERK phosphorylation after a combined insult of EtOH intoxication and burn injury compared with shams. However, the suppression in p-38 (Figure 2A) and ERK-1/2 (Figure 2B) phosphorylation was prevented in T-cells stimulated with anti-CD3 in the presence of PTP inhibitor pervanadate. There was no demonstrable change in the p-38 and ERK-1/2 total protein content in any group. In addition to anti-CD3, p-38, and ERK-1/2 phosphorylation was also measured in response to another T-cell mitogen Con A. Results shown in Figure 3 indicate that similar to anti-CD3, the suppression in Con A-mediated p-38 (Figure 3A) and ERK-1/2 (Figure 3B) phosphorylation was prevented in cells which were stimulated with Con A in the presence of pervanadate.

Figure 2.

Effects of pervanadate (PV) on anti-CD3 linked p-38 and extracellular-signal-regulated kinase (ERK)-1/2 phosphorylation and protein expression in mesenteric lymph node (MLN) T-cell after acute alcohol (EtOH) intoxication and burn injury. MLN T-cells were isolated (1 × 107 cells/ml), stimulated with anti-CD3 (1 μg/ml) in the presence or absence of PV (10 μM) for 5 minutes and lysed. Lysates were analyzed for p-38 (panel A) and ERK-1/2 (panel B) phosphorylation by Western blot. Blots were stripped and reprobed for p-38 and ERK-1/2 total protein contents in various lanes. Blots obtained from six animals in each group were analyzed using densitometry. Densitometric values for phosphorylation were normalized to the total protein and are shown in bar graph as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 compared with other groups.

Figure 3.

Effects of pervanadate (PV) on concanavalin A (Con A)-linked p-38 and extracellular-signal-regulated kinase (ERK)-1/2 phosphorylation and protein expression in mesenteric lymph node (MLN) T-cell after acute alcohol (EtOH) intoxication and burn injury. MLN T-cells were isolated (1 × 107 cells/ml), stimulated with Con A (5 μg/ml) in the presence or absence of PV (10 μM) for 5 minutes and lysed. Lysates were analyzed for p-38 (panel A) and ERK-1/2 (panel B) phosphorylation by Western blot. Blots were stripped and reprobed for p-38 and ERK-1/2 total protein contents in various lanes. Blots obtained from six animals in each group were analyzed using densitometry. Densitometric values for phosphorylation were normalized to the total protein and are shown in bar graph as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 compared with other groups.

In subsequent experiments, T-cells were directly stimulated with higher concentrations of pervanadate (200 μM and 500 μM). These doses of pervanadate were selected from a previously published study.12 Results as shown in Figure 4 indicate that pervanadate dose dependently increased p-38 and ERK-1/2 phosphorylation over basal values in sham and EtOH plus burn-injured rat T-cells (Figure 4). Furthermore, there was no significant difference in p-38 and ERK-1/2 phosphorylation between sham and EtOH plus burn-injured rat T-cell.

Figure 4.

Effect of direct stimulation of T-cells with pervanadate (PV) on p-38 and extracellular-signal-regulated kinase (ERK)-1/2 phosphorylation after acute alcohol (EtOH) intoxication and burn injury. Mesenteric lymph node (MLN) T-cells were isolated (1 × 107 cells/ml), stimulated with anti-CD3 (1 μg/ml), or with PV (200 and 500 μM) for 5 minutes and lysed. Lysates were analyzed for p-38 (panel A) and ERK-1/2 (panel B) phosphorylation. Blots were stripped and reprobed for p-38 and ERK-1/2 total protein in various lanes. Blots obtained from four animals in each group were analyzed using densitometry. Densitometric values for phosphorylation were normalized to the total protein and are shown in bar graph as mean ± SEM. * P < 0.05 compared with their respective sham groups.

Effect of Pervanadate on T-Cell IL-2 and IFN-γ Production

To determine whether inhibiting PTP by pervanadate prevents the suppression in T-cell IL-2 and IFN-γ production, T-cells were cultured with anti-CD3 in the presence or absence of pervanadate (10 μM) for 48 hours and supernatants were harvested for the measurement of IL-2 and IFN-γ production. To determine the effect of direct stimulation with the PTP inhibitor, T-cells were cultured in the presence of pervanadate (200 μM and 500 μM) for 48 hours and supernatants were harvested for the measurement of IL-2 and IFN-γ production. It is to be noted that IL-2 and IFN-γ were not detected in the supernatants harvested from T-cells cultured directly in the presence of pervanadate. Several studies have used high concentration of pervanadate to directly activate T-cell signaling molecules via T-cell receptor-independent mechanism.12–14 Similar to those studies, we also found thaT-cells stimulated directly with higher pervanadate concentrations (200–500 μM) did not exhibit a decrease in p-38 and ERK-1/2 in T-cells derived from EtOH and burn-injured rats compared with shams. But the cells cultured at these concentrations did not survive and therefore no IL-2 and IFN-γ were detected in the culture supernatants. It is possible that pervanadate at the higher concentrations becomes toxic to the cells and thereby the cells did not survive. These findings indicate that although the use of pervanadate at high concentrations is fine to understand the interaction between molecules, but to understand the cell function or the activation of signaling molecules in response to specific receptor (ie, T-cell receptor, TCR), it is important that we use pervanadate at low concentration. Accordingly, the use of low concentration (10 μM) has allowed us to evaluate the effect of pervanadate on T-cell p-38/ERK activation as well as the effector responses.

IL-2 and IFN-γ levels after anti-CD3 stimulation are shown in Figure 5A. There was a significant decrease in anti-CD3-mediated IL-2 and IFN-γ production in T-cells derived from EtOH plus burn-injured rats compared with shams. However, the decrease in IL-2 and IFN-γ after EtOH intoxication and burn injury was prevented in T-cells cultured in the presence of pervanadate (Figure 5A).

Figure 5.

Effect of protein tyrosine phosphatases (PTP) inhibitors pervanadate (PV) on mesenteric lymph node (MLN) T-cells interleukin (IL)-2 and interferon (IFN)-γ production after acute alcohol (EtOH) intoxication and burn injury. MLN T-cells (5 × 106 cells/ml) were cultured with anti-CD3 (wells precoated with 2 μg/ml, panel A) or Con A (5 μg/ml, panel B) in the presence or absence of PV (10 μM) in a 96-well plate at 37°C and 5% CO2. After 48 hours of culture, supernatants were harvested for the measurement of IL-2 and IFN-γ Values are means ± SEM from six animals in each group. *P < 0.05 compared with other groups.

In addition to anti-CD3, T-cell cytokine production was also measured in response to T-cell mitogen Con A. Similar to anti-CD3, the suppression in Con A-mediated production of T-cell IL-2 and IFN-γ was prevented in the group of cells which were cultured in the presence of pervanadate (Figure 5B).

DISCUSSION

The results presented in this article indicate that the burn size profoundly influences T-cell cytokine production after injury. Furthermore, a small burn (≤12.5%) which by itself may not cause T-cell suppression but when combined with prior EtOH exposure, it produces significant suppression in those cells. The findings further corroborate our previous studies indicating that up-regulation of phosphatases may cause a decrease in T-cell p-38 and ERK activation after EtOH intoxication and burn injury. We used anti-CD3 and Con A to stimulate cells in the present study. Although anti-CD3 stimulates cells via CD3 subunit of TCR complex, Con A requires a cell with major histocompatibility complex for T-cell activation. In our study, we did not use Con A to determine the role of antigen presenting cells rather we used Con A as an additional T-cell mitogen to confirm whether alterations in T-cell p-38 and ERK-1/2 are not specific to anti-CD3 stimulation. Altogether, the results presented in this article indicate that the suppression in T-cell p-38, ERK-1/2 phosphorylation and related decrease in IL-2 and IFN-γ production could result from an increase in activation of protein tyrosine phosphatases in T-cell after a combined insult of EtOH intoxication and burn injury.

Unlike majority of proteins which phosphorylates on tyrosine, threonine, or serine, p-38 and ERK phosphorylates on tyrosine and threonine and thus are referred to as dual phosphorylated proteins.18,19 Previous studies from our laboratory have shown a correlation between a decrease in p-38 and ERK-1/2 activation (ie, phosphorylation) and IL-2 production in MLN T-cell after EtOH intoxication and burn injury.17,23 There was no change in c-Jun N-terminal kinases activation under those conditions and thus c-Jun N-terminal kinases appears not to be critical in T-cell suppression after EtOH intoxication and burn injury. Several lines of evidence indicate that the stimulation of resting T-cells from healthy individuals with antibodies to T-cell receptor complex, CD3, Con A, or antigen initiates a cascade of events leading to the cell activation and effector functions such as the T-cell proliferation and production of cytokines.18,19 The earliest signaling events of the cascade include the phosphorylation of src family kinases (eg, P56lck and P59fyn). This leads to the activation of subsequent molecules including zeta-chain (TCR) associated protein kinase 70 kDa (ZAP-70) and phospholipase C-γ. Phospholipase C-γ hydrolyzes phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP) into inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) and diacyl glycerol which in turn respectively induces Ca2+ release and the activation of protein kinase C.19 This leads to the activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK). MAPK through another series of downstream signaling molecules leads to T-cell activation.18,19 The resultant activated T-cells mitotically divide and produce IL-2. IL-2 upon release interacts with IL-2 receptor present on T-cells and initiates another wave of signaling pathways including the activation of the janus kinase (JAK)-signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) and MAPK. Thus the activation of MAPK becomes critical for both TCR and IL-2-dependent pathway.18,19 However, the activation of these signaling molecules is tightly controlled by their corresponding phosphatases.

Under physiological conditions, there exists an equilibrium between PKs and PPs and this is critical for appropriate activation of signaling molecules.15,16,18,19 Similar to kinases, PPs is also a large family of members consisting of protein tyrosine, serine, and threonine kinases.15,16,18,19 Many of these phosphatases are expressed in T-cell. These include hemopoietic protein tyrosine phosphatase, Vaccinia H1-related phosphatase (VHR), VHR related mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatases X, and the serine/threonine-specific phosphatases type-1 (PP1) and type-2A (PP2A).15,16,18,19 Mitogen-activated protein kinases phosphatases (MKP) is another large family of phosphatases and is shown to regulate p-38 and ERK activation. In a previous study, we determined the role of MKP-1 (ie, a member of MKP) and found that the suppression in p-38 and ERK-1/2 after EtOH intoxication and burn injury is likely independent of MKP-1.17 We also determined the activation of PP1 and PP2A using phospho-antibodies specific for PP1α and PP2A and found that PP1 is likely the one that plays a predominant role in suppressed p-38 and ERK-1/2 activation after EtOH intoxication and burn injury. However, because p-38 and ERK-1/2 besides threonine, also phosphorylate tyrosine residue, it was not clear from the previous study whether PTP has any role in suppressed p-38 and ERK activation after EtOH intoxication and burn injury. Results presented in this article indicate that PTPs also play a role in suppressed T-cell p-38/ERK phosphorylation and cytokine production.

Earlier studies have implicated P59fyn, protein kinase C, and Ca2+ in T-cell suppression after burn and sepsis.25–27 We have shown that suppression of P59fyn and Ca2+ elevation is associated with an increase in prostaglandin E2 synthesis under those conditions.25,26 Because the activation of P59fyn and Ca2+ signaling precedes p-38 and ERK-1/2 activation, changes in either of these may potentially cause a change in p-38 and ERK-1/2 in T-cells in EtOH intoxication and burn injury. Whether or not a decrease in p-38 and ERK-1/2 phosphorylation in MLN T-cells from EtOH and burn-injured rats is due to a direct effect of EtOH intoxication and burn injury or is mediated via alteration in signaling molecules upstream to p-38 and ERK-1/2 remains unknown. Furthermore, it also remains to be established whether PTPs regulate p38/ERK directly or indirectly via molecules upstream to MAPK. Several potential factors may contribute to the loss of balance between PTPs and p-38/ERK pathway after EtOH intoxication and burn injury remains to be established. One possibility is the increase in corticosterone (a type of glucocorticoids in rodents) after EtOH intoxication and burn injury.23 Glucocorticoids have been implicated in altered balance between PKs and PPs.28,29 It is likely that increased corticosterone levels after a combined insult of EtOH intoxication and burn injury may up-regulate phosphatases such as protein tyrosine or serine/threonine phosphatases. Moreover, corticotrophin was shown to up-regulate PTPs.30 Furthermore, a role of other inflammatory factors (eg, IL-10 tumor necrosis factor-α, transforming growth factor-β, prostaglandin E, and inducible nitric oxide synthase derivatives) in altered T-cell signaling is also not ruled out. Recently, studies have also shown a role of natural killer T-cell, γ-δ T-cell and T-regulatory cells in suppressed immune responses after burn injury.31–33 Whether EtOH exposure before burn injury mediates its action by modulating natural killer T-cell, γ-δ T-cell, and/or T regulatory cells, remains to be established. It also remains unclear whether alterations in signaling molecules suppress T-cell effector responses directly or indirectly by influencing T-cell differentiation from TH1 to TH2. Thus more studies are needed to identify the role of these factors in T-cell functional deficits after EtOH intoxication and burn injury.

We recognize that although the present study was performed at a single time point (day 1 after injury), we have previously shown that the T-cell cytokine production remained significantly lower on day 2 after injury in the group of rats receiving EtOH and burn injury.7,23 An analysis of data revealed an approximate 33% decrease in T-cell IL-2 production on day 1, ~74% on day 2, and nearly ~90% decrease on day 3 from rats receiving a combined insult of EtOH intoxication and burn injury compared with shams. Similarly as compared with shams, the production of IFN-γ was also decreased by ~60% on day 1, ~78% on day 2, and ~85% on day 3 by T-cells in rats subjected to a combined insult of EtOH intoxication and burn injury compared with shams. Several previous studies have shown T-cell suppression up to 10 days after burn injury34,35 but whether or not EtOH intoxication delays recovery from burn injury remains to be answered. In addition to T-cell suppression, our previous studies have also examined additional markers of morbidity and mortality in this model.7,8,23,36–38 These studies indicated that a combined insult of EtOH intoxication and burn injury results in bacterial overgrowth, increased intestinal permeability, and increase in bacterial translocation.7,8,23,36–38 Although the increased permeability and bacterial overgrowth in the intestine after a combined insult of EtOH intoxication and burn injury may contribute to increased bacterial translocation, the process of infection involves not only the passage of bacteria from the intestinal lumen to extra-intestinal sites but also survivability of translocated bacteria in the extra-intestinal sites. Thus an evaluation of intestinal immune response in parallel to intestinal barrier function is critical. MLN, being the central lymph node connects various parts of the intestine and plays an important role in clearing bacteria originating from the intestine. Earlier we have also shown that T-cell plays an important role in bacterial clearance.7 Although the mechanisms by which T-cells prevent bacterial translocation remain to be unknown, the finding of decreased MLN T-cell effector responses (eg, IL-2 and IFN-γ production) likely contributes to a decrease in host’s ability to clear the translocated bacteria. Therefore, a suppression in T-cell functions because of altered p-38/ERK pathways may impair bacterial clearance leading to their multiplication and accumulation in MLN and other organs of the injured host.

In summary, a small burn injury may not sufficiently cause T-cell suppression but when it is combined with EtOH intoxication, it exacerbates T-cell suppression after burn injury. Similar to EtOH exposure, other additional insults such as smoke inhalation, wound infection, or other septic complications etc., also shown to exacerbate the postburn alterations.1,35,39–43 Furthermore, we found that an inhibition of PTPs with pervanadate prevented the decrease in T-cell p-38 and ERK-1/2 activation and cytokine production after a combined insult of EtOH intoxication and burn injury. These findings suggest a role of PTPs in suppressed T-cell p-38/ERK and cytokine production after EtOH intoxication and burn injury. However, whether the phosphatases-mediated decrease in IL-2 and IFN-γ production in EtOH plus burn animals is due to a suppression of T-cell function, or is due to a switch in T-cell phenotype remains to be established. Regardless of the mechanism, once the T-cell suppression is induced, this may hamper the ability of MLN to clear bacteria originating from intestine and thus becomes the source of infection in injured host.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by NIH through R01AA015731-01A2.

References

- 1.Choudhry MA, Rana SN, Kavanaugh MJ, et al. Impaired intestinal immunity and barrier function: a cause for enhanced bacterial translocation in alcohol intoxication and burn injury. Alcohol. 2004;33:199–208. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2004.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maier RV. Ethanol abuse and the trauma patient. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 2001;2:133–41. doi: 10.1089/109629601750469456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McGill V, Kowal-Vern A, Fisher SG, et al. The impact of substance use on mortality and morbidity from thermal injury. J Trauma. 1995;38:931–4. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199506000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McGwin G, Jr, Chapman V, Rousculp M, et al. The epidemiology of fire-related deaths in Alabama, 1992–1997. J Burn Care Rehabil. 2000;21:75–83. doi: 10.1097/00004630-200021010-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Messingham KA, Faunce DE, Kovacs EJ. Alcohol, injury, and cellular immunity. Alcohol. 2002;28:137–49. doi: 10.1016/s0741-8329(02)00278-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Szabo G, Mandrekar P, Verma B, et al. Acute ethanol consumption synergizes with trauma to increase monocyte tumor necrosis factor alpha production late postinjury. J Clin Immunol. 1994;14:340–52. doi: 10.1007/BF01546318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choudhry MA, Fazal N, Goto M, et al. Gut-associated lymphoid T-cell suppression enhances bacterial translocation in alcohol and burn injury. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2002;282:G937–G947. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00235.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kavanaugh MJ, Clark C, Goto M, et al. Effect of acute alcohol ingestion prior to burn injury on intestinal bacterial growth and barrier function. Burns. 2005;31:290–6. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2004.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Napolitano LM, Koruda MJ, Zimmerman K, et al. Chronic ethanol intake and burn injury: evidence for synergistic alteration in gut and immune integrity. J Trauma. 1995;38:198–207. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199502000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deitch EA. Role of the gut lymphatic system in multiple organ failure. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2001;7:92–8. doi: 10.1097/00075198-200104000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keshavarzian A, Holmes EW, Patel M, et al. Leaky gut in alcoholic cirrhosis: a possible mechanism for alcohol-induced liver damage. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:200–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.00797.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Choudhry MA, Sir O, Sayeed MM. TGF-beta abrogates TCR-mediated signaling by upregulating tyrosine phosphatases in T-cells. Shock. 2001;15:193–9. doi: 10.1097/00024382-200115030-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Imbert V, Peyron JF, Farahi FD, et al. Induction of tyrosine phosphorylation and T-cell activation by vanadate peroxide, an inhibitor of protein tyrosine phosphatases. Biochem J. 1994;297:163–73. doi: 10.1042/bj2970163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mukhopadhyay A, Manna SK, Aggarwal BB. Pervanadate-induced nuclear factor-kappaB activation requires tyrosine phosphorylation and degradation of IkappaBalpha. Comparison with tumor necrosis factor-alpha. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:8549–55. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.12.8549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mustelin T, Alonso A, Bottini N, et al. Protein tyrosine phosphatases in T-cell physiology. Mol Immunol. 2004;41:687–700. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2004.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saxena M, Mustelin T. Extracellular signals and scores of phosphatases: all roads lead to MAP kinase. Semin Immunol. 2000;12:387–96. doi: 10.1006/smim.2000.0219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li X, Schwacha MG, Chaudry IH, et al. A role of PP1/PP2A in mesenteric lymph node T-cell suppression in a two-hit rodent model of alcohol intoxication and injury. J Leukoc Biol. 2006;79:453–62. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0705369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dong C, Davis RJ, Flavell RA. MAP kinases in the immune response. Annu Rev Immunol. 2002;20:55–72. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.091301.131133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang Y, Wange RL. T-cell receptor signaling: beyond complex complexes. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:28827–30. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R400012200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Walker HL, Mason AD., Jr A standard animal burn. J Trauma. 1968;8:1049–51. doi: 10.1097/00005373-196811000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kleiber M. Body size and metabolic rate. Physiol Rev. 1947;27:511–41. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1947.27.4.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Choudhry MA, Ren X, Romero A, et al. Combined alcohol and burn injury differentially regulate P-38 and ERK activation in mesenteric lymph node T-cell. J Surg Res. 2004;121:62–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2004.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li X, Rana SN, Kovacs EJ, et al. Corticosterone suppresses mesenteric lymph node T-cells by inhibiting p38/ERK pathway and promotes bacterial translocation after alcohol and burn injury. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2005;289:R37–R44. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00782.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Choudhry MA, Uddin S, Sayeed MM. Prostaglandin E2 modulation of p59fyn tyrosine kinase in T lymphocytes during sepsis. J Immunol. 1998;160:929–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Choudhry MA, Ahmad S, Sayeed MM. Role of Ca2+ in prostaglandin E2-induced T-lymphocyte proliferative suppression in sepsis. Infect Immun. 1995;63:3101–5. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.8.3101-3105.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Choudhry MA, Fazal N, Namak SY, et al. PGE2 suppresses intestinal T-cell function in thermal injury: a cause of enhanced bacterial translocation. Shock. 2001;16:183–8. doi: 10.1097/00024382-200116030-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Faist E, Schinkel C, Zimmer S, et al. Inadequate interleukin-2 synthesis and interleukin-2 messenger expression following thermal and mechanical trauma in humans is caused by defective transmembrane signalling. J Trauma. 1993;34:846–53. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199306000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clark AR. MAP kinase phosphatase 1: a novel mediator of biological effects of glucocorticoids? J Endocrinol. 2003;178:5–12. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1780005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kassel O, Sancono A, Kratzschmar J, et al. Glucocorticoids inhibit MAP kinase via increased expression and decreased degradation of MKP-1. EMBO J. 2001;20:7108–16. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.24.7108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Paz C, Cornejo MF, Mendez C, et al. Corticotropin increases protein tyrosine phosphatase activity by a cAMP-dependent mechanism in rat adrenal gland. Eur J Biochem. 1999;265:911–18. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00759.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ni CN, MacConmara M, Zang Y, et al. Enhanced regulatory T-cell activity is an element of the host response to injury. J Immunol. 2006;176:225–36. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.1.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Palmer JL, Tulley JM, Kovacs EJ, et al. Injury-induced suppression of effector T-cell immunity requires CD1d-positive APCs and CD1d-restricted NKT cells. J Immunol. 2006;177:92–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.1.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schwacha MG, Ayala A, Chaudry IH. Insights into the role of gammadelta T lymphocytes in the immunopathogenic response to thermal injury. J Leukoc Biol. 2000;67:644–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.O’Suilleabhain C, O’Sullivan ST, Kelly JL, et al. Interleukin-12 treatment restores normal resistance to bacterial challenge after burn injury. Surgery. 1996;120:290–6. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6060(96)80300-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schwacha MG, Chaudry IH. The cellular basis of post-burn immunosuppression: macrophages and mediators. Int J Mol Med. 2002;10:239–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li X, Rana SN, Schwacha MG, et al. A novel role for IL-18 in corticosterone-mediated intestinal damage in a two-hit rodent model of alcohol intoxication and injury. J Leukoc Biol. 2006;80:367–75. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1205745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li X, Schwacha MG, Chaudry IH, Choudhry MA. Acute alcohol intoxication potentiates neutrophil-mediated intestine tissue damage following burn injury. Shock. 2008;29:377–83. doi: 10.1097/shk.0b013e31815abe80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rana SN, Li X, Chaudry IH, et al. Inhibition of IL-18 reduces myeloperoxidase activity and prevents edema in intestine following alcohol and burn injury. J Leukoc Biol. 2005;77:719–28. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0704396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alexander M, Chaudry IH, Schwacha MG. Relationships between burn size, immunosuppression, and macrophage hyperactivity in a murine model of thermal injury. Cell Immunol. 2002;220:63–9. doi: 10.1016/s0008-8749(03)00024-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Toliver-Kinsky TE, Cui W, Murphey ED, et al. Enhancement of dendritic cell production by fms-like tyrosine kinase-3 ligand increases the resistance of mice to a burn wound infection. J Immunol. 2005;174:404–10. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.1.404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Murphy TJ, Paterson HM, Mannick JA, et al. Injury, sepsis, and the regulation of Toll-like receptor responses. J Leukoc Biol. 2004;75:400–7. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0503233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Smith JW, Gamelli RL, Jones SB, et al. Immunologic responses to critical injury and sepsis. J Intensive Care Med. 2006;21:160–72. doi: 10.1177/0885066605284330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Alexander M, Daniel T, Chaudry IH, et al. Opiate analgesics contribute to the development of post-injury immunosuppression. J Surg Res. 2005;129:161–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2005.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]