Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common arrhythmia encountered in clinical practice, and is increasing in both incidence and prevalence[1, 2]. Over two million Americans currently have AF, and estimates project that between 5 and 12 million will be affected by 2050[1, 2]. AF is associated with substantial morbidity, including one third of all strokes in patients above the age of 65[3] and a two-fold increased risk of mortality[4, 5]. The costs attributable to the care of individuals with AF are in excess of $6.4 billion per year[3].

AF is often associated with hypertension and structural heart disease, and traditionally, has not been considered a genetic condition. However, a number of recent studies have demonstrated that AF and in particular, lone AF, have a substantial genetic basis[6–9]. Mutations in several ion channels have been identified in individuals with familial AF[10–17], although they appear to be rare causes of the arrhythmia[18, 19]. Recently, a genome wide associated study has led to the identification of genetic variants associated with common forms of AF. In the course of this review we will discuss the heritability of AF, the methods employed to identify causal variants underlying AF, and our current understanding of genetic variation implicated in AF.

Atrial fibrillation is a heritable condition

While familial forms of AF have long been reported, [20] a genetic predisposition for more common forms of AF has only recently been recognized. In 2003, Fox and coworkers studied more than 5,000 individuals whose parents were enrolled in the original Framingham Heart Study[8]. Over a 19 year follow up period, they found that the development of AF in the offspring was independently associated with parental AF, particularly if the Offspring cohort was restricted to those under the age of 75 and without antecedent heart disease. Having a parent with AF approximately doubled the four-year risk of developing AF, even after adjustment for risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and myocardial infarction.

Arnar and colleagues similarly described a genetic predisposition to AF in a study of more than 5,000 Icelanders in 2006[6]. After assessing relatedness from a nationwide genealogical database, eighty percent of those with AF were related to another individual with AF. The relative risk of AF for first-degree relatives of a family member with AF was 1.77, when compared to individuals in the general population. The relative risk for AF increased to 4.67 when the sample was restricted to individuals less than 60 years old.

Further evidence of the heritability of AF was demonstrated in a chart review of over two thousand patients with AF referred for evaluation at the Mayo Clinic[9]. Five percent of subjects had a family history of AF, and the number was as high as 15% among those with lone AF. In 2005, we found that nearly 40% of individuals with lone AF referred to the Arrhythmia Service at Massachusetts General Hospital had at least one relative with the arrhythmia, and a substantial number reported having multiple affected relatives[7]. In over 90% of cases, AF in the relatives could be verified. To obtain a crude index of heritability, we determined the prevalence of AF among each class of relative compared to that among age and sex-matched subjects. The relative risk of AF was increased among family members, and ranged from 2 fold in fathers to nearly 70 fold in male siblings.

Genetic studies in atrial fibrillation

Once a condition is found to be heritable, there are several techniques that are commonly employed to identify the genetic basis of a disease. These include linkage analysis, candidate gene resequencing and association studies. We will discuss each of these methods in the context of their application to AF.

Linkage analysis

The genes that underlie simple monogenic disorders with a Mendelian pattern of inheritance can be identified using linkage analysis. When passed from generation to generation, genetic markers that lie close together on the same chromosome are likely to be transmitted en bloc in proportion to their proximity to each other. A genome wide search for groups of markers that co-segregate with the disease as it travels through a family tree is performed to identify the approximate location of a genetic disease locus. Linkage studies report a logarithm of the odds or LOD score that reflects the likelihood of two markers or a marker and disease co-segregating when compared with chance alone. A LOD score of 3 or more (or odds of greater than a 1000:1) is considered statistically significant. Traditionally, restriction enzyme sites and microsatellite repeats have been used as genetic markers, but more recently, it has become possible to use single nucleotide polymorphisms, or SNPs[21]. The ease of use in genotyping has made SNPs the most widely used genetic markers today.

Linkage analysis can be used to narrow the search for a causative gene to a chromosomal locus, or relatively small region of the human genome associated with disease. However, this limited region may still contain hundreds of genes spread over millions of base pairs. Once a genetic locus is identified, online data from human genome databases that developed as a result of the Human Genome Project are used to identify candidate genes within the locus. These genes are then sequenced in affected individuals in an attempt to identify the sequence variants that correlate with the disease.

Once a base pair change is identified, it is important to differentiate between a mutation and a genetic polymorphism, or common variant in the genome. For a sequence alteration to be considered a mutation it must segregate with the disease, have a plausible mechanism, and not be found in normal controls. Ultimately, the mutation should be sufficient to cause the phenotype, either in a human kindred or in a genetic model organism.

While several genetic loci have been reported in kindreds with Mendelian AF in which specific genetic mutations have yet to be identified, [22–25] linkage analysis has facilitated the identification of individual mutations in several cases of familial AF. [10, 26]

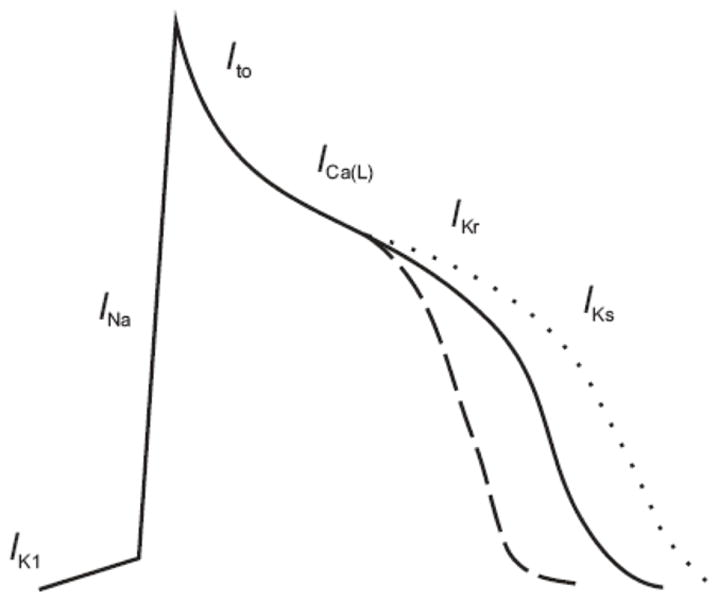

In one such family of Chinese descent, Chen and coworkers identified a mutation in KCNQ1[10], a potassium channel that underlies the slowly repolarizing current in cardiomyocytes known as IKs (see Figure 1). The investigators were able to map the disease locus to a 12 megabase region on the short arm of chromosome 11, in a four-generation family with AF. The KCNQ1 gene was located within this region, and sequencing revealed a serine to glycine missense mutation at position 140 (S140G) in affected family members. The S140G mutation is located in the first transmembrane-spanning segment[27] at the outer edges of the voltage-sensing domain and far from the pore-forming region of the potassium channel structure. The S140G mutation results in a gain of channel function, in contrast to mutations in KCNQ1 associated with the long QT syndrome that typically result in a loss of channel function. In cultured cells, expression of the S140G mutant channel resulted in dramatically enhanced potassium channel currents and markedly altered potassium channel gating kinetics, which would be predicted to increase IKs. Such an increase would be expected to lead to a shortening of the action potential duration and thus predispose atrial myocytes to reentry and subsequent AF (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Both gain of function and loss of function mutations in IKs have been associated with AF. Mutations in KCNQ1 and KCNE2 increase the current IKs, which is predicted to shorten the action potential (dashed line) in cardiac myocytes and render atrial myocytes susceptible to reentrant arrhythmias. Mutations in KCNA5 (Kv1.5) that are predicted to prolong the action potential duration (dotted line) have also been associated with AF.

While the identification of this mutation provided an initial inroad into the pathogenesis of AF, this family also illustrates our limited understanding of the role of the KCNQ1 channel in atrial versus ventricular repolarization. Specifically, it remains unclear why a mutation that results in an in vitro gain of function in KCNQ1 is associated with delayed ventricular repolarization, as manifested by a prolonged QT interval, in more than half of the individuals with the S140G mutation.

Other gain of function mutations in KCNQ1 have been associated with the short QT syndrome[28]. Hong and colleagues reported an unusual case of AF detected in utero and confirmed on electrocardiogram upon delivery of the newborn[29]. The infant’s electrocardiogram also displayed a short QT interval. Based on this association, they sequenced the KCNQ1 gene and found a valine to methionine mutation in position 141 (adjacent to the mutated position found by Chen and colleagues). Like the S140G mutation, in vitro expression of V141M mutant channels displayed markedly enhanced current density and altered gating kinetics.

More recently, Hodgson-Zingman and colleagues identified a frameshift mutation in NPPA in a family with AF[26]. The mutation in NPPA, which encodes atrial natriuretic peptide, resulted in increased levels of a circulating mutant peptide. Electrophysiological assessment in a rat heart model revealed decreased action potential duration, consistent with known mechanisms of reentrant mediated AF[30].

Candidate gene studies

A candidate gene can be any gene that is hypothesized to cause a disease. Based on the work relating KCNQ1 to AF, investigators have considered other potassium channels as potential candidate genes for AF and screened for mutations in these genes in cohorts of subjects with AF.

Otway and colleagues examined 50 kindreds with AF and amplified the genes for KCNQ1 and KCNE1-3, accessory subunits of KCNQ1[14]. They found a single mutation in KCNQ1 in only one family—an arginine to cysteine change at amino acid position 14 (R14C) in KCNQ1. Unlike the S140G mutation discovered by Chen and colleagues, R14C had no significant effect on KCNQ1/KCNE1 current amplitudes in cultured cells at baseline. However, upon exposure to hypotonic solution, mutant channels exhibited a marked increase in currents compared to wild type channels. Interestingly, of those who carried the R14C mutation, only those with left atrial dilatation had AF, leading the authors to propose a “two-hit” hypothesis for AF. They also identified a mutation in KCNE2 in two of the kindreds. Like the S140G mutation in KCNQ1, the mutation in KCNE2 (R27C) dramatically increased the amplitude of IKs[11].

Finally, other work has suggested that the relationship between potassium channels and AF extends beyond IKs. The work of Xia and colleagues may also implicate KCNJ2, an inward rectifier potassium channel that underlies the IK1 current, in AF[12]. In their work, a V93I mutation was found in all affected members in one kindred with familial AF. The V93I also lead to gain of function KCNJ2 channels, which increase potassium current amplitudes. However, there is still an incomplete understanding of how an increase in the background current IK1 might lead to atrial arrhythmias.

We have screened our cohort with lone AF for mutations in KCNQ1, KCNJ2, and KCNE1-5 and were unable to find any mutations in these genes[18]. These findings suggest that potassium channels are an uncommon cause of AF and there is much more to be learned about the diversity of molecular pathways that lead to this arrhythmia.

The genes encoding connexins, gap-junction proteins that mediate the spread of action potentials between cardiac myocytes, have also been examined as potential candidates for AF. Prior work has shown that mice with null alleles of GJA5, the gene for connexin40, exhibit atrial reentrant arrhythmias[31]. From this work, Gollob and coworkers considered this gene as a potential candidate in individuals with idiopathic AF who underwent pulmonary vein isolation surgery[32]. An analysis of DNA isolated from their cardiac tissue showed that four of the fifteen subjects had mutations in GJA5 that markedly interfered with the electrical coupling between cells. In three of the patients, DNA isolated from their lymphocytes lacked the same mutation in GJA5 indicating that the connexin40 mutations had been acquired after fertilization or was a somatic mutation. One of the four individuals carried the mutation in both cardiac tissue and lymphocytes consistent with a germline rather than somatic mutation. However, more information about the transmission of AF in relatives of these individuals was not available.

Association studies

Although traditional methods such as linkage analysis can be applied to families where the phenotype and pattern of inheritance are consistent with a monogenic disorder, the mode of transmission for AF is less clear. Association studies have been used in an attempt to identify the genetic basis of AF and other apparently complex traits. In an association study the frequency of a genetic marker, such as a SNP, is compared between individuals with an outcome (cases) and those without an outcome (controls). Over the past ten years, many case-control and cohort studies have been performed in subjects with AF, leading to the identification of variants associated with disease. These studies have typically tested a small number of variants and have been directed at candidate genes previously believed to be involved in AF. Examples include genes encoding products involved in regulation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone axis [33–40], calcium handling[41], as well as neurohormonal[39] and lipoprotein[42] pathways. Additionally, genes encoding gap junction proteins[43, 44], ion channels[15, 45–49], interleukins[50, 51], signaling molecules[34, 45, 52], and mediators of other molecular pathways[53] have been examined (summarized in Table 2). Unfortunately, these studies have been limited by a low prior probability of any polymorphism truly being associated with AF. Further complicating these analyses are the small sample sizes, a lack of replication in distinct populations, as well as phenotypic and genetic heterogeneity.

Table 2.

Polymorphisms associated with atrial fibrillation

| Gene | Variant | Cases | Controls | OR | P value | Replicated? | Comments | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| -- | rs2200733 | 3,913 | 22,092 | 1.72 | 3.3×10−41 | Yes | Identified in GWAS | [62] |

| -- | rs10033464 | 3,913 | 22,092 | 1.39 | 6.9×10−11 | Yes | Identified in GWAS | [62] |

| ACE | D/D | 51 | 289 | 1.5 | 0.016 | Yes | In patients with CHF | [34] |

| ACE | D/D | 404 | 520 | 1.89 | <0.001 | - | [36] | |

| Aldosterone synthase | T-344C | 63 | 133 | 2.65 | 0.03 | No | In patients with CHF | [40] |

| Angiotensinogen | M235T | 250 | 250 | 2.5 | <0.001 | No | [33] | |

| Angiotensinogen | G-6A | 250 | 250 | 3.3 | 0.005 | No | [33] | |

| Angiotensinogen | G-217A | 250 | 250 | 2.0 | 0.002 | No | [33] | |

| Angiotensinogen | T174M | 968 | 8267 | 1.2 | 0.05 | No | [37] | |

| Angiotensinogen | 20 C/C | 968 | 8267 | 1.5 | 0.01 | No | [37] | |

| CETP | Taq1B | 97 | 97 | 0.35 | 0.05 | No | [42] | |

| Connexin 40 | −44A | 14 | 16 | 5.3 | 0.0019 | Yes | [44] | |

| Connexin 40 | −44A, +71G | 173 | 232 | 1.514 | < 0.006 | - | [43] | |

| Endothelin-2 | A985G | 26 | 84 | 5.89 | 0.018 | No | In patients with HCM | [39] |

| eNOS | 894T/T | 51 | 289 | 3.2 | 0.001 | No | In patients with CHF | [34] |

| eNOS | T-786C | 331 | 441 | 1.4 | 0.05 | No | [45] | |

| GNB3 | C825T | 291 | 292 | 0.46 | 0.02 | No | [52] | |

| Heat shock protein 70 | Met439Thr | 48 | 194 | 2.43 | 0.016 | No | In postoperative CABG patients | [53] |

| Interleukin 6 | G-174C | 26 | 84 | 3.25 | 0.006 | No | In postoperative CABG patients | [50] |

| Interleukin 10 | A-592C | 196 | 873 | 0.32 | 3.70×10−03 | No | Lone AF | [51] |

| KCNE4 | E145D | 142 | 238 | 1.66 | 0.044 | No | [49] | |

| KCNE5 | 97T | 158 | 96 | 0.52 | 0.007 | No | [48] | |

| KCNH2 | K897T | 1207 | 2475 | 1.25 | 0.00033 | No | [46] | |

| MinK | 38G | 108 | 108 | 1.8 | 0.024 | Yes | [47] | |

| MinK | 38G | 331 | 441 | 1.73 | <0.005 | - | [45] | |

| MMP2 | C1306T | 196 | 873 | 8.1 | 1.26×10−02 | No | Lone AF | [51] |

| SLN | G 65C | 147 | 92 | 0.011 | No | [41] |

In recent years, genome wide association studies (GWAS) have been made possible by advancements in genotyping technology that allow investigators to assay hundreds of thousands of SNPs spread over the entire human genome. The studies are typically executed using a case-control study design[54]. GWAS attempt to identify novel genetic polymorphisms that are significantly more or less common in a group with a disease as compared to a control group. Since the markers are spread over the entire genome, these experiments give no weight to existing candidate genes. Such studies have been used successfully in the past several years to identify potential novel pathways for diabetes[55], obesity[56], coronary heart disease[57, 58], macular degeneration[59], and repolarization[60].

While GWAS have the potential to identify new pathways for disease, they also have a number of limitations. In particular, with hundreds of thousands of individual associations being tested, these studies have a high likelihood of producing false positive associations. There is still discussion within the field of what the threshold level should be for genome-wide significance[61]. False positive results can also emerge from population stratification or the failure to properly control for ethnicity, thus resulting in over or under representation of spurious ethnic specific markers. While variations in study design have been proposed in an effort to eliminate false associations, ultimately replication of the associations in other populations is the best method of validation[54].

The biological significance of the identified variants is another concern. Most variants found in genetic association studies have been associated with relatively weak effects, with typical odds ratios ranging from ~1.3 to 1.5. While such variants may generate new ideas about disease pathogenesis, understanding the biological mechanisms by which the majority of variants confer disease susceptibility remains challenging.

Recently, a team led by the researchers at deCODE genetics have reported the results of a GWAS for AF. Gudbjartsson and colleagues examined over 300,000 SNPs and identified two polymorphisms on the long arm of chromosome 4 (4q25) that were highly associated (p = 3.3×10−41) with AF or atrial flutter in a group of Icelanders[62]. In order to improve both the validity and generalizability of the findings, the study was replicated in other populations in Iceland, Sweden, the United States and Hong Kong. Neither variant was correlated with obesity, hypertension, or myocardial infarction suggesting that the genetic variants are not associated with AF by affecting those risk factors.

How do the variants on chromosome 4 lead to AF? At present, the mechanism of action of these variants is unclear. Interestingly, these SNPs lie upstream from a gene that could plausibly play a role in the pathogenesis of AF, the paired-like homeodomain transcription factor 2, PITX2. This gene is known to be critical in the development of the left atrium[63–66], pulmonary myocardium[67], and in the suppression of left atrial pacemakers cells in early development[68]. One can speculate that these variants may alter the function of PITX2 either in early development or in adulthood and thus predispose to AF. However, currently there is no direct link between the PITX2 gene and these non-coding variants more than 50,000 base pairs away. Future work examining the correlation between these variants and PITX2 RNA levels, protein levels, or tissue specificity will hopefully clarify the mechanism underlying the association of these SNPs with AF.

Refining genetic studies of atrial fibrillation

In order to continue to improve upon the utility of genetic studies for AF we will need to overcome a number of obstacles. A critical step in any genetic study is the ability to correctly assign the diagnosis. AF represents a particular challenge because many individuals are asymptomatic, some have paroxysmal disease, and yet others develop AF late in life. Genotypic and phenotypic heterogeneity further complicate the classification of AF. Rather than a single entity, AF may represent the final common pathway for a number of distinct pathogenic insults such as heart failure, hypertension, or thyroid abnormalities.

In order to address these challenges, we will have to continue to improve upon the characterization and classification of AF. The identification of endophenotypes, or subtle, heritable traits that co-segregate with AF, may help to refine ongoing genetic studies. For AF, endophenotypes such as specific P wave morphologies, pulmonary venous anatomy as assessed by computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging, or biomarkers that are heritable and easily detectable may be helpful.

Summary

Recent studies of AF have identified mutations in a series of ion channels; however, these mutations appear to be relatively rare causes of AF. A genome wide association study has identified novel variants on Chromosome 4 associated with AF, although the mechanism of action for these variants remains unknown. Ultimately, a greater understanding of the genetics of AF should yield insights into novel pathways, therapeutic targets, and diagnostic testing for this common arrhythmia.

Table 1.

Genes and loci implicated in familial atrial fibrillation

| Genes | Chr | Gene name | Effect | Inheritance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11p15.5 | KCNQ1/KvLQT1 | Increases IKs, Expected to shorten APD | AD | [10, 14] | |

| 21q22.1 | KCNE2/MiRP1 | Increases IKs | AD | [11] | |

| 17q23.1-24.2 | KCNJ2 | Increases IK1; Expected to shorten APD | AD | [12] | |

| 12p13 | KCNA5 | Loss of IKur; prolongs APD | AD | [13] | |

| 3p21 | SCN5A | Hyperpolarizing shift of resting membrane potential; Expected to prolong APD | AD | [15–17] | |

| 1p36-p35 | NPPA | Results in mutant atrial natriuretic peptide; associated with shortened APD | AD | [26] | |

| Genetic Loci | Chr | Gene | Comments | Inheritance | Reference |

| 5p13 | Unknown | Associated with sudden death | AR | [24] | |

| 6q14-q16 | Unknown | Overlaps with locus for DCM | AD | [23] | |

| 10q22-q24 | Unknown | Overlaps with locus for DCM | AD | [22] | |

| 10p11-q21 | Unknown | AD | [25] |

Abbreviations: Chr, Chromosome; AD, autosomal dominant; AR, autosomal recessive; DCM, dilated cardiomyopathy.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the Disque Deane Foundation to Dr. Ellinor and an NIH training grant (5T32HL007575) to Dr. Lubitz.

References

- 1.Miyasaka Y, Barnes ME, Gersh BJ, et al. Secular trends in incidence of atrial fibrillation in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1980 to 2000, and implications on the projections for future prevalence. Circulation. 2006;114(2):119–25. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.595140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Go AS, Hylek EM, Phillips KA, et al. Prevalence of diagnosed atrial fibrillation in adults: national implications for rhythm management and stroke prevention: the AnTicoagulation and Risk Factors in Atrial Fibrillation (ATRIA) Study. JAMA. 2001;285(18):2370–5. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.18.2370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coyne KS, Paramore C, Grandy S, et al. Assessing the direct costs of treating nonvalvular atrial fibrillation in the United States. Value Health. 2006;9(5):348–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2006.00124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benjamin EJ, Wolf PA, D’Agostino RB, et al. Impact of atrial fibrillation on the risk of death: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 1998;98(10):946–52. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.10.946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gajewski J, Singer RB. Mortality in an insured population with atrial fibrillation. JAMA. 1981;245(15):1540–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arnar DO, Thorvaldsson S, Manolio TA, et al. Familial aggregation of atrial fibrillation in Iceland. Eur Heart J. 2006;27(6):708–12. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ellinor PT, Yoerger DM, Ruskin JN, et al. Familial aggregation in lone atrial fibrillation. Hum Genet. 2005;118(2):179–84. doi: 10.1007/s00439-005-0034-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fox CS, Parise H, D’Agostino RB, Sr, et al. Parental atrial fibrillation as a risk factor for atrial fibrillation in offspring. JAMA. 2004;291(23):2851–5. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.23.2851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Darbar D, Herron KJ, Ballew JD, et al. Familial atrial fibrillation is a genetically heterogeneous disorder.[comment] Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2003;41(12):2185–92. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(03)00465-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen YH, Xu SJ, Bendahhou S, et al. KCNQ1 gain-of-function mutation in familial atrial fibrillation. Science. 2003;299(5604):251–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1077771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang Y, Xia M, Jin Q, et al. Identification of a KCNE2 gain-of-function mutation in patients with familial atrial fibrillation. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;75(5):899–905. doi: 10.1086/425342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xia M, Jin Q, Bendahhou S, et al. A Kir2.1 gain-of-function mutation underlies familial atrial fibrillation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;332(4):1012–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.05.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olson TM, Alekseev AE, Liu XK, et al. Kv1.5 channelopathy due to KCNA5 loss-of-function mutation causes human atrial fibrillation. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15(14):2185–91. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Otway R, Vandenberg JI, Guo G, et al. Stretch-sensitive KCNQ1 mutation A link between genetic and environmental factors in the pathogenesis of atrial fibrillation? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49(5):578–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.09.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen LY, Ballew JD, Herron KJ, et al. A common polymorphism in SCN5A is associated with lone atrial fibrillation. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2007;81(1):35–41. doi: 10.1038/sj.clpt.6100016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Darbar D, Kannankeril PJ, Donahue BS, et al. Cardiac sodium channel (SCN5A) variants associated with atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2008;117(15):1927–35. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.757955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ellinor PT, Nam EG, Shea MA, et al. Cardiac sodium channel mutation in atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm. 2008;5(1):99–105. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2007.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ellinor PT, Moore RK, Patton KK, et al. Mutations in the long QT gene, KCNQ1, are an uncommon cause of atrial fibrillation. Heart. 2004;90(12):1487–8. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2003.027227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ellinor PT, Petrov-Kondratov VI, Zakharova E, et al. Potassium channel gene mutations rarely cause atrial fibrillation. BMC Med Genet. 2006;7:70. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-7-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wolff L. Familial auricular fibrillation. New Eng J Med. 1943;229:396–8. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Consortium TIH. A haplotype map of the human genome. Nature. 2005;437(7063):1299–320. doi: 10.1038/nature04226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brugada R, Tapscott T, Czernuszewicz GZ, et al. Identification of a genetic locus for familial atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 1997;336(13):905–11. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199703273361302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ellinor PT, Shin JT, Moore RK, et al. Locus for atrial fibrillation maps to chromosome 6q14–16. Circulation. 2003;107(23):2880–3. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000077910.80718.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oberti C, Wang L, Li L, et al. Genome-wide linkage scan identifies a novel genetic locus on chromosome 5p13 for neonatal atrial fibrillation associated with sudden death and variable cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2004;110(25):3753–9. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000150333.87176.C7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Volders PG, Zhu Q, Timmermans C, et al. Mapping a novel locus for familial atrial fibrillation on chromosome 10p11-q21. Heart Rhythm. 2007;4(4):469–75. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2006.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hodgson-Zingman DM, Karst ML, Zingman LV, et al. Atrial natriuretic peptide frameshift mutation in familial atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(2):158–65. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0706300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schenzer A, Friedrich T, Pusch M, et al. Molecular Determinants of KCNQ (Kv7) K+ Channel Sensitivity to the Anticonvulsatn Retigabine. Journal of Neuroscience. 2005;25(20):5051–60. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0128-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bellocq C, van Ginneken ACG, Bezzina CR, et al. Mutation in the KCNQ1 Gene Leading to the Short QT-Interval Syndrome. Circulation. 2004;109:2394–7. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000130409.72142.FE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hong K, Piper DR, Diaz-Valdecantos A, et al. De novo KCNQ1 mutation responsible for atrial fibrillation and short QT syndrome in utero. Cardiovasc Res. 2005;68(3):433–40. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nattel S. New ideas about atrial fibrillation 50 years on. Nature. 2002;415(6868):219–26. doi: 10.1038/415219a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hagendorff A, Schumacher B, Kirchhoff S, et al. Conduction disturbances and increased atrial vulnerability in connexin40-deficient mice analyzed by transesophageal stimulation. Circulation. 1999;99:1508–15. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.11.1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gollob MH, Jones DL, Krahn AD, et al. Somatic mutations in the connexin 40 gene (GJA5) in atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(25):2677–88. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tsai CT, Lai LP, Lin JL, et al. Renin-angiotensin system gene polymorphisms and atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2004;109(13):1640–6. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000124487.36586.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bedi M, McNamara D, London B, et al. Genetic susceptibility to atrial fibrillation in patients with congestive heart failure. Heart Rhythm. 2006;3(7):808–12. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2006.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yamashita T, Hayami N, Ajiki K, et al. Is ACE gene polymorphism associated with lone atrial fibrillation? Jpn Heart J. 1997;38(5):637–41. doi: 10.1536/ihj.38.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fatini C, Sticchi E, Gensini F, et al. Lone and secondary nonvalvular atrial fibrillation: role of a genetic susceptibility. Int J Cardiol. 2007;120(1):59–65. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2006.08.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ravn LS, Benn M, Nordestgaard BG, et al. Angiotensinogen and ACE gene polymorphisms and risk of atrial fibrillation in the general population. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2008;18(6):525–33. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e3282fce3bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tsai CT, Hwang JJ, Chiang FT, et al. Renin-angiotensin system gene polymorphisms and atrial fibrillation: a regression approach for the detection of gene-gene interactions in a large hospitalized population. Cardiology. 2008;111(1):1–7. doi: 10.1159/000113419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nagai T, Ogimoto A, Okayama H, et al. A985G polymorphism of the endothelin-2 gene and atrial fibrillation in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circ J. 2007;71(12):1932–6. doi: 10.1253/circj.71.1932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Amir O, Amir RE, Paz H, et al. Aldosterone synthase gene polymorphism as a determinant of atrial fibrillation in patients with heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 2008;102(3):326–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2008.03.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nyberg MT, Stoevring B, Behr ER, et al. The variation of the sarcolipin gene (SLN) in atrial fibrillation, long QT syndrome and sudden arrhythmic death syndrome. Clin Chim Acta. 2007;375(1–2):87–91. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2006.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Asselbergs FW, Moore JH, van den Berg MP, et al. A role for CETP TaqIB polymorphism in determining susceptibility to atrial fibrillation: a nested case control study. BMC Med Genet. 2006;7:39. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-7-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Juang JM, Chern YR, Tsai CT, et al. The association of human connexin 40 genetic polymorphisms with atrial fibrillation. Int J Cardiol. 2007;116(1):107–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2006.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Firouzi M, Ramanna H, Kok B, et al. Association of human connexin40 gene polymorphisms with atrial vulnerability as a risk factor for idiopathic atrial fibrillation. Circ Res. 2004;95(4):e29–33. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000141134.64811.0a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fatini C, Sticchi E, Genuardi M, et al. Analysis of minK and eNOS genes as candidate loci for predisposition to non-valvular atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J. 2006;27(14):1712–8. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sinner MF, Pfeufer A, Akyol M, et al. The non-synonymous coding IKr-channel variant KCNH2-K897T is associated with atrial fibrillation: results from a systematic candidate gene-based analysis of KCNH2 (HERG) Eur Heart J. 2008 doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lai LP, Su MJ, Yeh HM, et al. Association of the human minK gene 38G allele with atrial fibrillation: evidence of possible genetic control on the pathogenesis of atrial fibrillation. Am Heart J. 2002;144(3):485–90. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2002.123573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ravn LS, Hofman-Bang J, Dixen U, et al. Relation of 97T polymorphism in KCNE5 to risk of atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiol. 2005;96(3):405–7. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.03.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zeng Z, Tan C, Teng S, et al. The single nucleotide polymorphisms of I(Ks) potassium channel genes and their association with atrial fibrillation in a Chinese population. Cardiology. 2007;108(2):97–103. doi: 10.1159/000095943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gaudino M, Andreotti F, Zamparelli R, et al. The -174G/C interleukin-6 polymorphism influences postoperative interleukin-6 levels and postoperative atrial fibrillation. Is atrial fibrillation an inflammatory complication? Circulation. 2003;108(Suppl 1):II195–9. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000087441.48566.0d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kato K, Oguri M, Hibino T, et al. Genetic factors for lone atrial fibrillation. Int J Mol Med. 2007;19(6):933–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schreieck J, Dostal S, von Beckerath N, et al. C825T polymorphism of the G-protein beta3 subunit gene and atrial fibrillation: association of the TT genotype with a reduced risk for atrial fibrillation. Am Heart J. 2004;148(3):545–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2004.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Afzal AR, Mandal K, Nyamweya S, et al. Association of Met439Thr substitution in heat shock protein 70 gene with postoperative atrial fibrillation and serum HSP70 protein levels. Cardiology. 2008;110(1):45–52. doi: 10.1159/000109406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Risch NJ. Searching for genetic determinants in the new millennium. Nature. 2000;405(6788):847–56. doi: 10.1038/35015718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Saxena R, Voight BF, Lyssenko V, et al. Genome-wide association analysis identifies loci for type 2 diabetes and triglyceride levels. Science. 2007;316(5829):1331–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1142358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Frayling TM, Timpson NJ, Weedon MN, et al. A common variant in the FTO gene is associated with body mass index and predisposes to childhood and adult obesity. Science. 2007;316(5826):889–94. doi: 10.1126/science.1141634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.McPherson R, Pertsemlidis A, Kavaslar N, et al. A common allele on chromosome 9 associated with coronary heart disease. Science. 2007;316(5830):1488–91. doi: 10.1126/science.1142447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Helgadottir A, Thorleifsson G, Manolescu A, et al. A common variant on chromosome 9p21 affects the risk of myocardial infarction. Science. 2007;316(5830):1491–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1142842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dewan A, Liu M, Hartman S, et al. HTRA1 promoter polymorphism in wet age-related macular degeneration. Science. 2006;314(5801):989–92. doi: 10.1126/science.1133807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Arking DE, Pfeufer A, Post W, et al. A common genetic variant in the NOS1 regulator NOS1AP modulates cardiac repolarization. Nat Genet. 2006;38(6):644–51. doi: 10.1038/ng1790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hunter DJ, Kraft P. Drinking from the Fire Hose--Statistical Issues in Genomewide Association Studies. New England Journal of Medicine. 2007;357(5):436–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp078120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gudbjartsson DF, Arnar DO, Helgadottir A, et al. Variants conferring risk of atrial fibrillation on chromosome 4q25. Nature. 2007;448(7151):353–7. doi: 10.1038/nature06007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gage PJ, Suh H, Camper SA. Dosage requirement of Pitx2 for development of multiple organs. Development. 1999;126(20):4643–51. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.20.4643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Campione M, Ros MA, Icardo JM, et al. Pitx2 expression defines a left cardiac lineage of cells: evidence for atrial and ventricular molecular isomerism in the iv/iv mice. Dev Biol. 2001;231(1):252–64. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.0133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Franco D, Campione M. The role of Pitx2 during cardiac development. Linking left-right signaing and congenital heart diseases. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2003;13:157–63. doi: 10.1016/s1050-1738(03)00039-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Logan M, Pagan-Westphal SM, Smith DM, et al. The transcription factor Pitx2 mediates situs-specific morphogenesis in response to left-right asymmetric signals. Cell. 1998;94(3):307–17. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81474-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mommersteeg MT, Brown NA, Prall OW, et al. Pitx2c and Nkx2–5 are required for the formation and identity of the pulmonary myocardium. Circ Res. 2007;101(9):902–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.161182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mommersteeg MT, Hoogaars WM, Prall OW, et al. Molecular pathway for the localized formation of the sinoatrial node. Circ Res. 2007;100(3):354–62. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000258019.74591.b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]