Abstract

Numerous studies with the neural activity marker Fos indicate that cocaine activates only a small proportion of sparsely distributed striatal neurons. Until now, efficient methods were not available to assess neuroadaptations induced specifically within these activated neurons. We used fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) to purify striatal neurons activated during cocaine-induced locomotion in naive and cocaine-sensitized cfos-lacZ transgenic rats. Activated neurons were labeled with an antibody against β-galactosidase, the protein product of the lacZ gene. Cocaine induced a unique gene expression profile selectively in the small proportion of activated neurons that was not observed in the nonactivated majority of neurons. These genes included altered levels of the immediate early genes arc, fosB, and nr4a3, as well as genes involved in p38 MAPK signaling and cell-type specificity. We propose that this FACS method can be used to study molecular neuroadaptations in specific neurons encoding the behavioral effects of abused drugs and other learned behaviors.

Introduction

A major hypothesis of current neurobiological research on cocaine addiction is that chronic cocaine exposure causes long-lasting neuroadaptations within the striatum and other components of the mesolimbic dopamine reward circuit, leading to compulsive drug use and long-term relapse vulnerability (Nestler, 2001; Shaham and Hope, 2005; Kalivas, 2009; Bowers et al., 2010; Wolf and Ferrario, 2010). However, this hypothesis is based on numerous studies limited to measuring neuroadaptations in homogenates of brain regions or in neurons selected independently of their activation state during behavior.

The distinction between neuroadaptations in activated versus nonactivated neurons is important because they may play different roles in the physiological, behavioral, and psychological effects of cocaine. Numerous studies with the neural activity marker Fos indicate that cocaine activates only a small proportion of sparsely distributed neurons in the striatum. Following context-specific locomotor sensitization, we have shown that Fos is induced only when rats were injected in the drug-paired environment and not in a nonpaired environment (Mattson et al., 2008; Koya et al., 2009). Most importantly, we have shown that these selectively activated neurons play a causal role in the learned association between cocaine and the drug-paired environment that mediates context-specific sensitization (Koya et al., 2009). Thus neuroadaptations within selectively activated striatal neurons may play unique and important roles in learning during context-specific sensitization and other drug-induced behaviors.

Until now, technical limitations have made it difficult to assess molecular alterations within the small numbers of sparsely distributed neurons selectively activated during behavior. Techniques such as laser capture microdissection (Kwon and Houpt, 2010) and double-label immunohistochemistry (Berretta et al., 1992; Gerfen et al., 1995; Peters et al., 1996) are capable of identifying molecular alterations selectively within activated neurons, but these techniques have very low throughput or are not quantitative. Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) can be an efficient tool for purifying adult neuronal populations for molecular analysis (Liberles and Buck, 2006; Lobo et al., 2006). However, FACS has not been used to purify neurons based on their activation state. In the current study, we used FACS to purify the interspersed cocaine-activated striatal neurons from transgenic cfos-lacZ rats and compared their unique patterns of gene expression with those in the nonactivated majority of neurons.

Materials and Methods

Animals.

Female cfos-lacZ transgenic rats (Kasof et al., 1995; Koya et al., 2009) and female Sprague Dawley rats (Charles River) were housed individually in standard plastic cages in a temperature- and humidity-controlled room. They were maintained on a 12:12 h reverse light:dark cycle (lights on at 8:00 P.M.), and allowed ad libitum access to food and water. They were acclimatized to these housing conditions for a minimum of 7 d before drug treatments. Experimental procedures were approved by the National Institute on Drug Abuse Animal Care and Use Committee.

Drug treatments.

For acute cocaine experiments, rats were injected with cocaine (30 mg/kg, i.p.; n = 8) or saline (1 ml/kg; n = 6) and placed in a round Plexiglas chamber (38 cm diameter). Rats were killed 90 min after injections to obtain brain tissue. This treatment was repeated three times on separate days to obtain three biological replicates for microarray analysis. Additionally, three independent biological replicates were similarly produced for quantitative PCR (qPCR). For qPCR analyses of arc, pdyn, and adora2a, only these three independent biological replicates were used. For qPCR analyses of fosB, nr4a3, kcnc1, and map2k6, we also used remaining RNA from each of the microarray samples.

For repeated cocaine experiments, female rats were sensitized with four injections of cocaine (15 mg/kg, i.p.) administered once every second day. On injection days, each rat was placed in a 43 × 43 cm square Plexiglas locomotor activity chamber (Med Associates) to habituate for 30 min. Rats were injected with cocaine and locomotor activity was recorded as distance traveled for 60 min. Following the fourth repeated cocaine injection, rats remained in their home cage for 7–8 d. On test day, rats were habituated for 30 min in the locomotor activity chambers and then injected with cocaine (30 mg/kg, i.p.) or saline vehicle. Rats were decapitated and brains were extracted 90 min after injections. The entire sensitization treatment was repeated three times over separate weeks to obtain three biological replicates of each group for qPCR analysis.

Cell dissociation.

Striatal tissue was dissociated to obtain a single-cell suspension. Rats were decapitated and their striata extracted within 2 min. Each striatum was minced with razor blades on an ice-cold glass plate and placed in 1 ml of Hibernate A [catalog number (Cat#) HA-LF; Brain Bits]. Striata were enzymatically digested in 1 ml of Accutase per striatum (Cat# SCR005; Millipore Bioscience Research Reagents) with end-over-end mixing for 30 min at 4°C. Tissue was centrifuged for 2 min at 425 × g and resuspended in 300 μl of ice-cold Hibernate A. All subsequent centrifugation steps were performed at 4°C.

Digested striatal tissue was mechanically dissociated by trituration. Four striata were combined into one Eppendorf tube and triturated 10 times with a large-diameter Pasteur pipette (∼1.3 mm). Tubes were briefly placed on ice for large tissue pieces to settle; 600 μl of cloudy suspension containing dissociated cells was transferred to a 15 ml Falcon tube on ice. Six hundred microliters of fresh Hibernate A were added to the original Eppendorf tube and then trituration steps were repeated as above with medium- and small-diameter pipettes (∼0.8 mm and ∼0.4 mm). Each cloudy suspension containing dissociated cells was pooled with the previous suspension.

Remaining cell clusters in the pooled cell suspension were removed by filtration through prewetted 100 μm and 40 μm cell strainers (Falcon brand, BD Biosciences). Small cellular debris in the suspension was reduced by centrifuging the filtrate for 3 min at 430 × g through a three-step density gradient of Percoll (Cat# P1644; Sigma). The cloudy top layer (∼2 ml) containing debris was discarded. Cells in the remaining layers were resuspended in the remaining Percoll solution and centrifuged for 5 min at 550 × g. The pellet was resuspended in 1 ml of Hibernate A.

Immunolabeling and FACS.

Dissociated cells were fixed and permeabilized by adding an equal volume of ethanol for a final concentration of 50% ethanol and kept on ice for 15 min with occasional mixing. Cells were centrifuged for 2 min at 425 × g and resuspended in RNase-free PBS. Cells were incubated with a biotinylated primary antibody against NeuN (1:1000 dilution, Cat# MAB377B, Millipore Bioscience Research Reagents) and a primary antibody against β-galactosidase (β-gal; 1:10,000 dilution, Cat# 4600-1409, Biogenesis). Cells were rotated end-over-end in primary antibody for 30 min at 4°C. Cells were washed with 800 μl of PBS and then centrifuged for 3 min at 425 × g. The pellet was resuspended in 700 μl of PBS. Cells were incubated with fluorescently labeled streptavidin (streptavidin-phycoerythrin, 1:1000 dilution, Cat# SA1004-1, Invitrogen) and secondary antibody (Alexa Fluor 488-labeled anti-goat IgG, 1:1000 dilution, Cat# A-11055, Invitrogen) and rotated end-over-end for 15 min. Cells were washed with 800 μl of PBS, centrifuged for 3 min at 425 × g, and resuspended in 1 ml of PBS.

Immunolabeled cells were scanned and sorted at the Johns Hopkins Bayview Campus flow cytometry core facility. A FACSAria (BD) was used for cell sorting. Control samples were analyzed first to determine optimal criteria for sorting test samples. Specifically, fixed cells without antibody treatment were used to set the light scatter gate. Fixed cells treated with fluorescent secondary antibody, but no primary antibody, were then used to set thresholds for endogenous tissue fluorescence and nonspecific binding by streptavidin or secondary antibody. Next, control samples single-labeled with primary and secondary antibody for each protein (NeuN or β-gal) were used to compensate for fluorescent overlap in neighboring channels. Finally, test samples labeled with both fluorescent markers were analyzed and sorted. Sorted cells were collected into low-binding tubes (Cat# 022431081, Eppendorf) with 100 μl of PBS in each tube.

RNA extraction.

After sorting, samples containing either β-gal-positive or β-gal-negative cells from cocaine-injected rats or all NeuN-positive cells from saline-injected rats were centrifuged for 8 min at 2650 × g at 18°C. NeuN-negative cells from saline-injected rats were centrifuged for 8 min at 6000 × g at 18°C. For microarray experiments, RNA was extracted with Trizol Reagent (Cat# 15596-026, Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Quality and quantity of RNA were assessed using the Bioanalyzer Picochip (Cat# 5067-1513, Agilent Technologies). For qPCR experiments, RNA was extracted with RNEasy Micro kit (Cat# 74004; Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions with DNase treatment. Quantity and purity of RNA was assessed using a Nanodrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific).

Microarray experiments.

Microarrays were used to analyze RNA from NeuN-positive and NeuN-negative cells from saline-injected rats, and β-gal-positive and β-gal-negative neurons from cocaine-injected rats. As described above in the drug treatment section, microarrays contained three biological replicates for each of the four sample types. Five microliters of total RNA from each sample were labeled using the Illumina TotalPrep RNA Amplification Kit (Cat# IL1791; Ambion) in a two-step process of cDNA synthesis followed by in vitro RNA transcription with biotin-16-UTP. Biotin-labeled cRNA (0.75 μg) was hybridized for 16 h to Illumina Sentrix Rat Ref12_v1 BeadChips (Cat# BD-27-303; Illumina). Biotinylated cRNA hybridized to the chip was detected with Cy3-labeled streptavidin and quantified using Illumina's BeadStation 500GX Genetic Analysis Systems scanner. All labeling and analysis was done at the Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Campus Lowe Family Genomics Core.

Real-time quantitative PCR.

Real-time quantitative PCR was used to validate FACS and microarray results. RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA using the RETROscript kit (Cat# AM1710, Ambion) with an oligo(dT) primer. Each 25 μl PCR included 12.5 μl of Taqman Gene Expression Master Mix (Cat #4369514; Applied Biosystems), 1.1 μl each of 20 μm forward and reverse primers, 0.25 μl of 100 μm FAM-labeled probe, 5 μl of water, and 5 μl of 1 ng/μl cDNA. Primer and probe combinations (Table 1) were designed using the Roche Universal Probe Library Assay Design Center to be intron-spanning. PCRs were monitored using the Opticon Light Cycler (Biorad). The program began with 20 plate reads at 50°C for photobleaching, followed by 5 min at 95°C, and then 40 cycles of 20 s at 94°C, 1 min at 60°C, and a plate read.

Table 1.

Primers and probes used for qPCR

| Gene | Forward primer | Reverse primer | Probe | Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| c-fos | cagcctttcctactaccattcc | acagatctgcgcaaaagtcc | #67 | 2.14 |

| fosB | tgcagctaaatgcagaaacc | ctcttcgagctgatccgttt | #109 | 1.87 |

| arc | gctgaagcagcagacctga | ttcactggtatgaatcactgctg | #79 | 1.94 |

| nr4a3 | acgcccagagaccttgatt | cacgtgctcagcgtctgt | #123 | 2.01 |

| pdyn | atcggccatcctatcacct | agcctgtggatgagtgacct | #129 | 1.99 |

| drd2 | tctgcaccgttatcatgaagtc | tctccatttccagctcctga | #118 | 2.03 |

| adora2a | gcagcgctagtttcgaagtc | cggcttcagggttctgag | #78 | 1.98 |

| kcnc1 | cttatcaaccggggagtacg | aatgacagggctttctttgc | #22 | 2.01 |

| map2k6 | ttggagcctatagtggagctg | ctattaactgtggcccgtatcc | #77 | 2.09 |

| dusp1 | agccataactttgtttttcagactc | tggcagtgcacaaacacc | #67 | 1.94 |

Standard curve reactions were first run for each gene to determine amplification efficiency (Table 1). Expression levels for each amplified gene were calculated using efficiencyΔCq, where ΔCq = Cq(experimental gene) − Cq(reference gene) for each biological replicate. Gorasp2 was chosen as a reference gene because it was not differently expressed between neurons and glia in microarray analyses. It was further validated as a reference gene due to equal qPCR amplification across all samples when loading the same amount of template. Technical assay triplicate Cq values were averaged before calculating ΔCq for each gene in a sample. For each mRNA measured in qPCR, gene expression values were averaged across biological replicates. Then, to reflect fold-change values, we divided this average by the average gene expression values of NeuN-positive cells from saline-injected rats. These values are indicated as means and SEs in the graphs and tables.

Immunohistochemistry.

Brain tissue was obtained from wild-type female Sprague Dawley rats following the same acute and repeated cocaine treatments described above for the microarray and qPCR experiments. However, 90 min after test day injections, rats were deeply anesthetized with isoflurane and perfused with 100 ml of PBS followed by 400 ml of 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA). Brains were postfixed in PFA for 2 h and transferred to 30% sucrose solution at 4°C for 2–3 d. Brains were frozen on powdered dry ice and kept at −80°C until sectioning. Coronal sections were cut 40 μm thick between bregma 2.5 and −0.5 (Paxinos and Watson, 1998).

Sections were immunolabeled for Fos and Arc. Briefly, sections were washed three times in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) and permeabilized for 30 min in TBS with 0.2% Triton X-100. Sections were washed again in TBS and incubated in primary antibodies diluted in PBS with 0.3% Triton X-100 for 24 h on a shaker at 4°C. We used a rabbit polyclonal anti-c-Fos antibody (1:500 dilution, Cat# sc-52, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and a mouse monoclonal Arc antibody (1:100 dilution, Cat# sc-17839, Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Sections were washed three times in TBS and incubated in secondary antibodies diluted in PBS for 1.5 h on a shaker at room temperature. We used Alexa Fluor 488-labeled donkey anti-rabbit antibody (1:200 dilution, Cat# A21206, Invitrogen) and Alexa Fluor 568-labeled goat anti-mouse antibody (1:200 dilution, Cat# A11004, Invitrogen). Sections were washed in TBS, mounted onto chrome alum-coated slides, and coverslipped with VectaShield hard-set mounting media.

Fluorescent images of Fos and Arc immunoreactivity in caudate–putamen and NAc (∼2.0 mm anterior to bregma) were captured using a CCD camera (Coolsnap Photometrics, Roper Scientific) attached to a Zeiss Axioskop 2 microscope. Images for counting labeled cells were taken at 200× magnification; images for determining Fos and Arc colocalization were taken at 400× magnification. Labeled cells from four hemispheres per rat were automatically counted using IPLab software for Macintosh, version 3.9.4 r5 (Scanalytics). Counts from all four hemispheres were averaged to obtain a single value for each rat.

Data analysis.

Locomotor sensitization data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA with repeated measures for the main effect of time over 4 injection days. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. Microarray data were analyzed using DIANE 6.0, a spreadsheet-based microarray analysis program based on SAS JMP 7.0, as previously described (Garg et al., 2009). Fluorescence intensity data from microarrays were subject to filtering by detection p values and Z normalization. Sample quality was analyzed using scatter plots, principal component analysis, and gene sample Z-score-based hierarchical clustering to exclude possible outliers. ANOVA tests were then used to eliminate genes with larger variances within each comparison group. Genes were identified as differentially expressed if p < 0.01, absolute Z-ratio ≥ 1.5, and false discovery ratio (fdr) < 0.07. For qPCR data, one-way ANOVA was used to compare data for each gene. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. For Fos and Arc immunohistochemistry, a t test assuming unequal variance was used to calculate statistical significance, set at p < 0.05.

Results

cfos-lacZ transgenic rats

The cfos-lacZ transgene in these rats is regulated by a c-fos promoter similar to that in the endogenous c-fos gene and is thus similarly activated in neurons by high levels of excitatory synaptic input (Shin et al., 1990; Labiner et al., 1993; Sgambato et al., 1997). The protein product of the cfos-lacZ transgene, β-gal, is coexpressed with c-Fos in strongly activated neurons (Koya et al., 2009) and used to label activated striatal neurons in the following FACS purification procedure.

FACS purification of activated striatal neurons following single acute cocaine injections

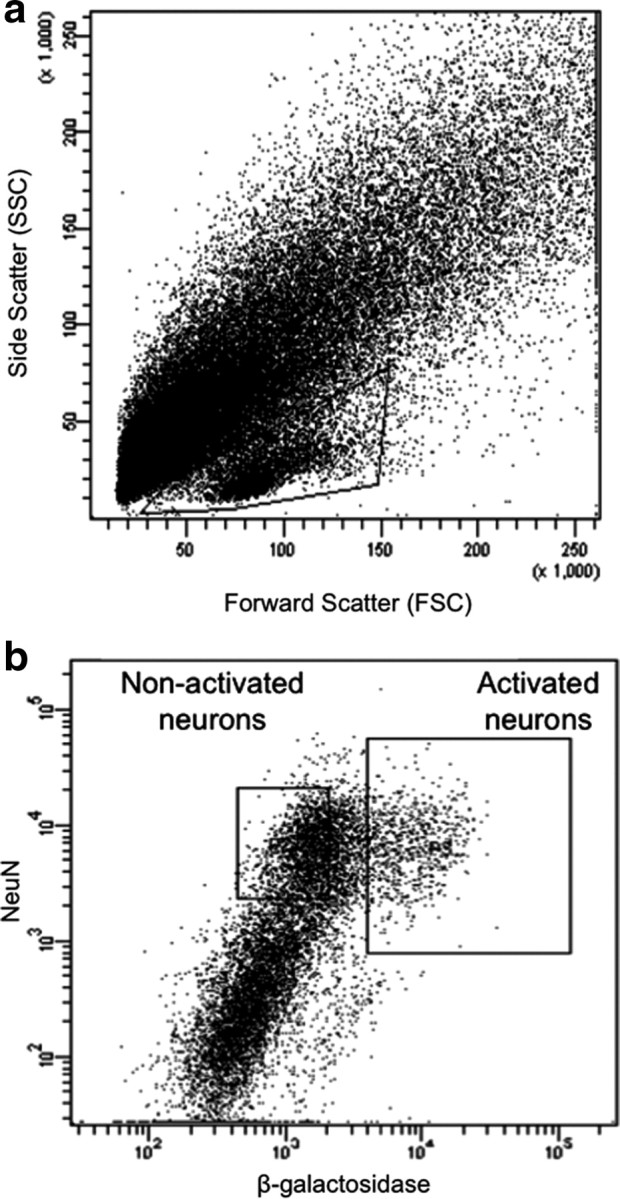

Whole striata were obtained from cfos-lacZ rats 90 min following acute injections of 30 mg/kg cocaine or saline outside their home cage. Dissociated striatal cells from similarly treated rats were pooled before FACS purification for each of the biological replicates in subsequent microarray and qPCR analyses. Dissociated striatal cells were initially analyzed according to their forward and side light-scattering characteristics (Fig. 1a). The majority of NeuN-labeled neurons were found within a strip of events along the lower part of the plot. Thus, all subsequent analyses were forward gated to include only events found within this strip.

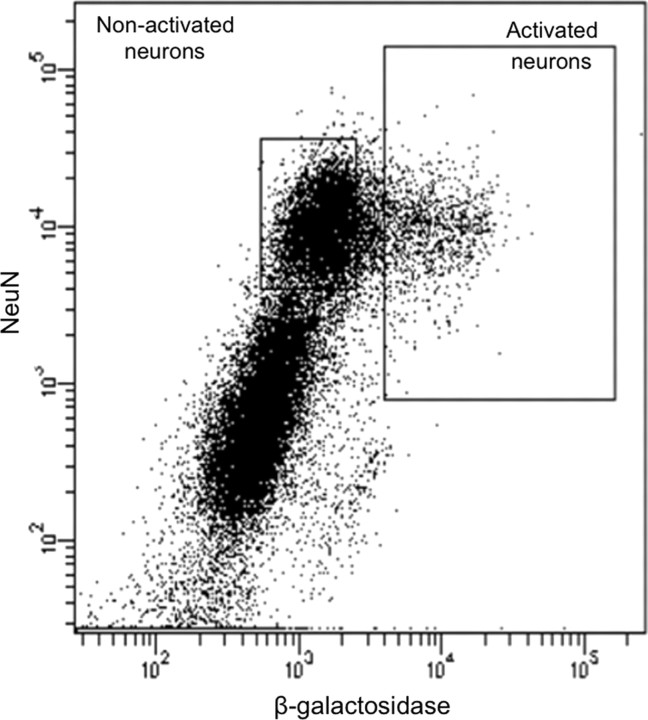

Figure 1.

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting of β-gal-labeled neurons from rats treated with a single injection of cocaine. a, Light scatter plot in which each dot represents one event (cell or debris). Forward scatter is a measure of size; side scatter is a measure of granularity. The “gate,” indicated by the solid-line box, encompasses all events that are analyzed on subsequent fluorescence plots. This gate allows analysis of cells and exclusion of debris. b, Fluorescence plot in which each dot represents one event. NeuN antibody labels all neurons; β-galactosidase antibody labels activated neurons. Two collection gates, indicated by the solid-line boxes, encompass activated and nonactivated neurons that were collected for further analysis.

Cells within this gate were separated according to their degree of immunolabeling with the neuronal marker NeuN and the neural activation marker β-gal. In tissue obtained from cocaine-injected rats, ∼15% of NeuN-labeled neurons had high levels of β-gal (Fig. 1b), which corresponded to ∼100,000 β-gal-labeled neurons per rat. All β-gal-labeled cells coexpressed NeuN, indicating that only neurons expressed β-gal. In contrast, very few NeuN-labeled neurons obtained from saline-injected rats expressed the activation markers β-gal or Fos, which supports β-gal and Fos immunoreactivity as markers of neural activation in cocaine-injected rats. The low numbers of β-gal-expressing neurons from saline-injected rats did not provide enough cells for subsequent molecular analyses. Thus, we used only NeuN labeling to separate neuronal from non-neuronal cells in all subsequent experiments with striatal tissue obtained from saline-injected rats. Overall, ∼30% of all striatal cell bodies were NeuN positive, which corresponded to ∼600,000 striatal neurons per rat. When FACS-purified cells were examined with fluorescence microscopy, all cells were round and devoid of processes (Fig. 2). Microscopic observation confirmed that FACS-sorted cells were appropriately labeled for NeuN and β-gal immunoreactivity. Samples of FACS-purified cells were found to be >90% pure when assessed with a second round of flow cytometry (data not shown).

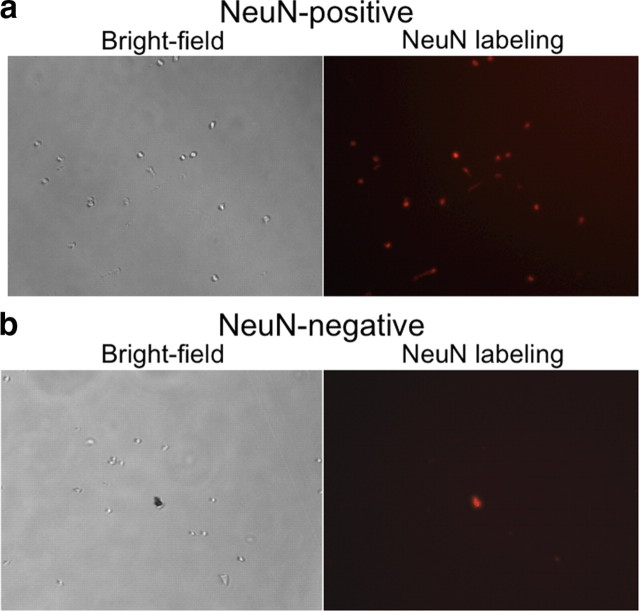

Figure 2.

Microscope photos of FACS-purified cells and debris. a, b, Bright-field and fluorescence images of NeuN-positive (neural) (a) and NeuN-negative (glial) (b) cells after fluorescence-activated cell sorting. All cells are round and devoid of processes. NeuN labeling is red. In b, there is a piece of debris that is autofluorescent (shows up in every fluorescent light channel).

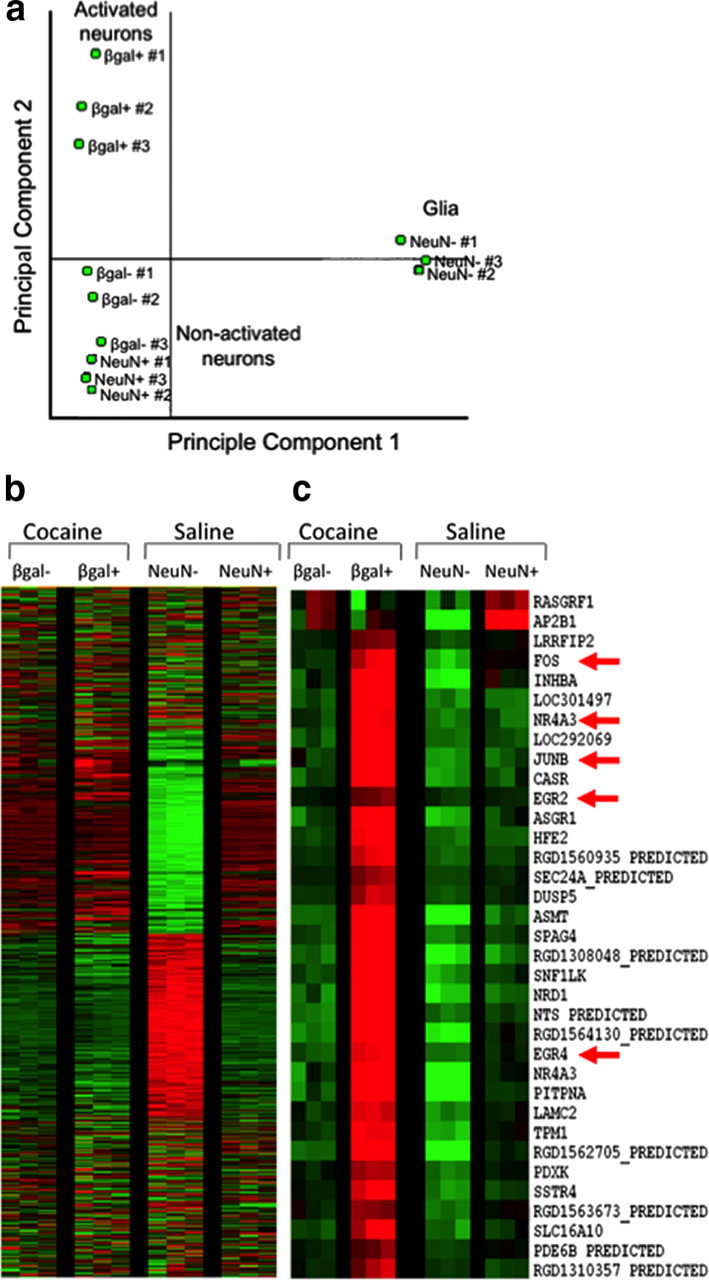

We determined selectivity of our FACS purification procedure with microarray to analyze gene expression patterns of the FACS-purified cells. We compared gene expression in β-gal-positive and β-gal-negative neurons from cocaine-injected rats as well as NeuN-positive and NeuN-negative cells from saline-injected rats. Principal component and cluster analysis indicated that the primary differentiating factor was whether the cells were neurons or glia (Fig. 3a). The second differentiating factor was β-gal expression used to separate activated from nonactivated neurons. Genes were identified as differentially expressed if p < 0.01, absolute Z-ratio ≥ 1.5, and fdr < 0.07. We found that 125 genes were increased and 467 genes were decreased in β-gal-positive neurons relative to β-gal-negative neurons obtained from the same striatal tissue of cocaine-injected rats (Fig. 3b). When the same β-gal-positive neurons from cocaine-injected rats were compared to control samples of all NeuN-labeled neurons from saline-injected rats, 133 genes were increased and 890 genes were decreased in the β-gal-positive neurons. Notably the two control groups—β-gal-negative neurons from cocaine-injected rats and all NeuN-labeled neurons from saline-injected rats—produced very similar gene expression patterns; gene expression was not significantly different between these control groups (Fig. 3b).

Figure 3.

Microarray analysis of cells sorted from rat striata after a single injection of cocaine or saline. a, Principal component analysis demonstrates that the primary differentiating factor among these samples was whether the cells were neurons or glia. The second differentiating factor was whether cells were activated (β-gal positive) or nonactivated (β-gal negative and NeuN positive). b, Heat maps display expression of thousands of genes in the four samples: activated β-gal-positive and nonactivated β-gal-negative neurons from cocaine-treated rats, and NeuN-positive neurons and NeuN-negative cells from saline-treated rats. Each row is one gene; each column is one sample; each group had three biological replicates. Green indicates decreased expression, and red indicates increased expression. Note that the NeuN-negative cells (glia) have a gene expression pattern vastly different from that of all three neuron groups. c, Enlarged portion of heat map focused on fos and related IEGs. Many IEGs are upregulated in the activated β-gal-positive neurons, including nr4a3, junB, egr2, and egr4.

Specific genes found in the different sample groups confirmed separation of activated from nonactivated neurons, as well as neuronal from non-neuronal cells using FACS (Table 2). β-gal-positive neurons from cocaine-injected rats expressed higher levels of many neural activation marker genes relative to β-gal-negative neurons from the same cocaine-injected rats or all NeuN-labeled neurons from saline-injected rats (Fig. 3c). These activity marker genes included c-fos, junB, arc, egr family (1, 2, 4), and nr4a3 (Guzowski et al., 2005). Interestingly, these β-gal-positive neurons also expressed significantly higher levels of the D1 dopamine receptor cell-type specific marker prodynorphin gene and significantly lower levels of the D2 dopamine receptor gene.

Table 2.

Summary of microarray and qPCR data from the acute cocaine experiment

| Gene symbol | Description | Gene ID | Microarray | Quantitative PCR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fos | c-fos; FBJ osteosarcoma oncogene; Immediate early gene | 314322 | +2.7-fold | F(2,9) = 1.887, p = 0.207 |

| β-gal + vs β-gal−: p = 0.229 | ||||

| β-gal+ vs NeuN+: p = 0.09 | ||||

| β-gal− vs NeuN+: p = 0.446 | ||||

| FosB | fra-2; FBJ osteosarcoma oncogene B; Immediate early gene | 308411 | — | F(2,11) = 5.520, p < 0.05 |

| β-gal+ vs β-gal−: +6.3-fold; n = 5, 6; p < 0.05 | ||||

| β-gal+ vs NeuN+: +7.5-fold; n = 5, 3; p < 0.05 | ||||

| β-gal− vs NeuN+: p = 0.938 | ||||

| Arc | Activity-regulated cytoskeleton-associated protein | 54323 | +4.6-fold | F(2,8) = 17.402, p < 0.005 |

| β-gal+ vs β-gal−: +6.6-fold; n = 4, 4; p < 0.005 | ||||

| β-gal+ vs NeuN+: +3.4-fold; n = 4, 3; p < 0.005 | ||||

| β-gal− vs NeuN+: p = 0.419 | ||||

| Nr4a3 | Nuclear receptor subfamily 4, group A, member 3; transcription factor | 58853 | +5.2-fold | F(2,9) = 11.456, p < 0.005 |

| β-gal+ vs β-gal−: +8.0-fold; n = 4, 5; p < 0.005 | ||||

| β-gal+ vs NeuN+: +5.1-fold; n = 4, 3; p < 0.01 | ||||

| β-gal− vs NeuN+: p = 0.742 | ||||

| Pdyn | Prodynorphin; peptide found in D1-expressing striatal neurons | 29190 | +2.3-fold | F(2,6) = 70.047, p < 0.001 |

| β-gal+ vs β-gal−: +3.6-fold; n = 3, 3; p < 0.001 | ||||

| β-gal+ vs NeuN+: +3.1-fold; n = 3, 3; p < 0.001 | ||||

| β-gal− vs NeuN+: p = 0.515 | ||||

| Adora2a | Adenosine A2a receptor; found in D2-expressing striatal neurons | 25369 | −3.0-fold | F(2,8) = 2.690, p = 0.128 |

| β-gal+ vs β-gal−: p = 0.204 | ||||

| β-gal+ vs NeuN+: p = 0.051 | ||||

| β-gal− vs NeuN+: p = 0.342 | ||||

| Kcnc1 | Kv4; Kv3.1; Potassium voltage-gated channel, Shaw-related subfamily, member 1 | 25327 | −2.6-fold | F(2,9) = 16.942, p < 0.005 |

| β-gal+ vs β-gal−: −2.2-fold; n = 4, 5; p < 0.01 | ||||

| β-gal+ vs NeuN+: −3.1-fold; n = 4, 3; p < 0.001 | ||||

| β-gal− vs NeuN+: −1.4-fold; p = 0.031 | ||||

| Map2k6 | Mkk6; Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 6; activator of p38 MAPK | 114495 | −5.2-fold | F(2,9) = 17.196, p < 0.005 |

| β-gal+ vs β-gal−: −7.9-fold; n = 4, 5; p < 0.05 | ||||

| β-gal+ vs NeuN+: −15.1-fold; n = 4, 3; p < 0.001 | ||||

| β-gal− vs NeuN+: −1.9-fold; p = 0.013 |

One-way ANOVA (F and p values are shown in Quantitative PCR column) was used to compare gene expression in three groups of cells: β-gal-positive neurons and β-gal-negative neurons from the same rats after a single injection of cocaine, and all neurons (NeuN-positive; NeuN+) from different rats after a single injection of saline. Fold-level changes are relative to control levels in NeuN + cells. Positive fold-level changes indicate higher levels, while negative fold-level changes indicate lower levels, than in NeuN + control samples.

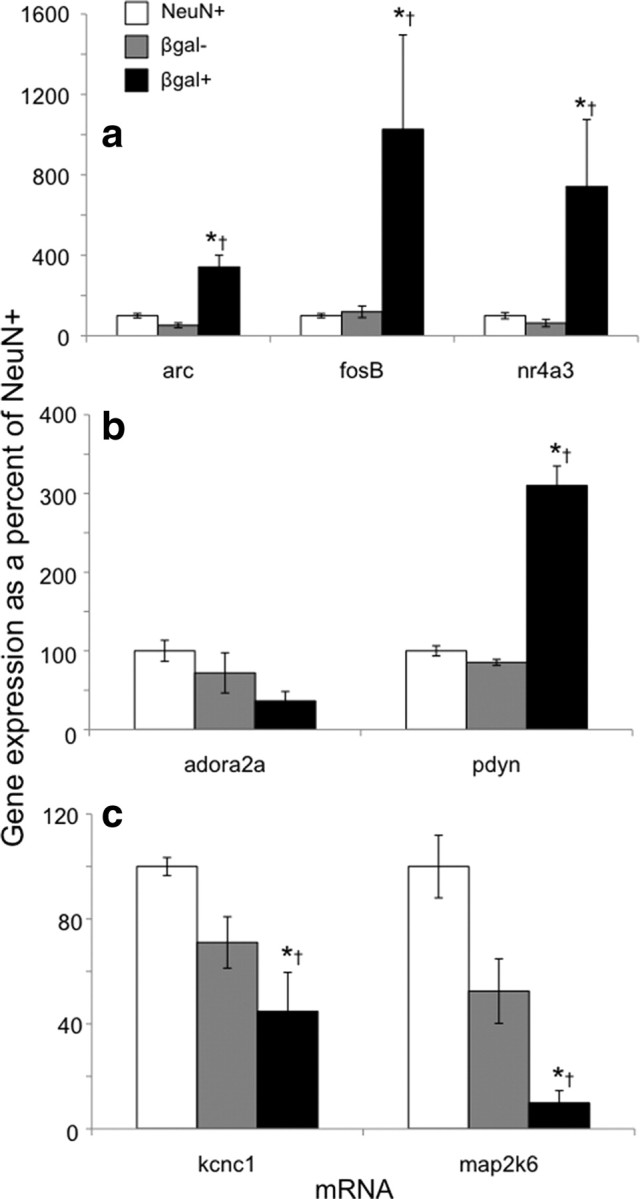

Microarray gene expression data were validated using qPCR. The activity marker genes fosB, arc, and nr4a3 were expressed at higher levels in β-gal-positive neurons from cocaine-injected rats relative to both β-gal-negative neurons from the same cocaine-injected rats and to all neurons from saline-injected rats (Fig. 4a; data and statistical information in Table 2). β-gal-positive neurons also expressed higher levels of the prodynorphin gene (Fig. 4b). While β-gal-positive neurons had apparently lower levels of expression for several genes, including the A2A adenosine receptor, the Kv3.1 potassium channel, and map2k6/MEKK6 genes, only Kv3.1 and map2k6/MEKK6 expression levels were statistically different using qPCR (Fig. 4c). Overall, gene expression alterations assessed with qPCR were nearly identical to gene expression alterations assessed by microarray experiments.

Figure 4.

Quantitative PCR demonstrates a different gene expression profile for β-gal-positive neurons after acute cocaine injections from that of β-gal-negative neurons from the same rats, or of all neurons from saline-injected rats. qPCR assays confirm microarray results. a, mRNA levels for the immediate early genes arc, fosB, and nr4a3 are increased in β-gal-positive neurons. b, mRNA levels for the D1-type cell marker prodynorphin (pdyn) are increased in β-gal-positive neurons, while only a trend is apparent for the A2A adenosine receptor (adora2a). c, mRNA levels for the Kv3.1 potassium channel subunit (kcnc1) and the kinase that activates p38 MAPK (map2k6) are decreased in β-gal-positive neurons. For expression values, n, and p values, see Table 2. *p < 0.05 versus NeuN-positive neurons from saline-injected rats. †p < 0.05 versus β-gal-negative neurons from cocaine-injected rats.

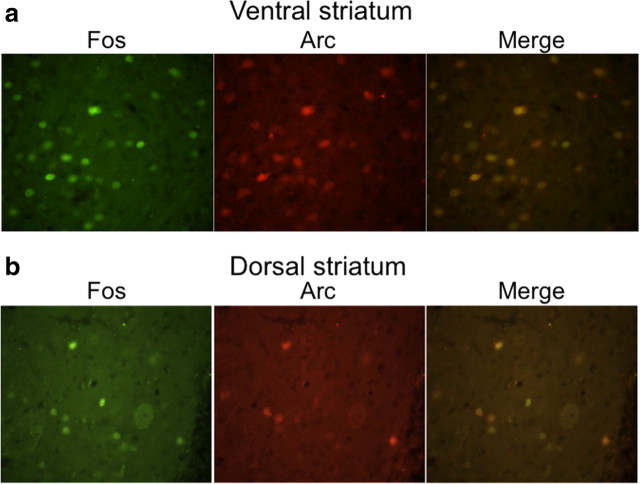

To determine whether mRNA alterations in activated neurons were reflected at the protein level, we used immunohistochemical analysis of coronal brain sections from cocaine- and saline-injected wild-type female rats (Fig. 5). These sections did not undergo dissociation or FACS, and therefore immunohistochemical analysis was not affected by the cell dissociation found in the FACS procedure. In ventral striatum from cocaine-injected rats (Fig. 5a), the neural activity markers Fos and Arc were coexpressed in the same cells: 85 ± 4% of all Fos-positive cells were Arc positive, while 82 ± 3% of all Arc-positive cells were Fos positive. Cocaine injections produced a 2.7-fold increase in Fos-labeled neurons and a 2.7-fold increase in Arc-labeled neurons. In dorsal striatum from cocaine-injected rats (Fig. 5b), 80 ± 2% of all Fos-positive cells were Arc positive, while 86 ± 3% of all Arc-positive cells were Fos positive. Cocaine injections produced a 4.4-fold increase in Fos-labeled neurons and a 3.8-fold increase in Arc-labeled neurons.

Figure 5.

Fos and Arc are coexpressed in ventral striatum (a) and dorsal striatum (b) after a single injection of cocaine. Fos-expressing nuclei are labeled green; Arc-expressing neurons are labeled red. Right-hand panels merge the Fos and Arc panels.

FACS purification of activated striatal neurons from cocaine-sensitized rats

In the second FACS experiment, all rats were sensitized with repeated cocaine injections. Repeated cocaine administration in the locomotor box enhanced cocaine-induced locomotion: locomotion on day 7 was 180 ± 18% of day 1 locomotion (main effect of time over four repeated injections, F(3,363) = 24.9, p < 0.001), which indicated significant psychomotor sensitization. Seven days later on test day, cocaine or saline was administered to rats in the same locomotor box. Ninety minutes later, striatal tissue including NAc was extracted and cells were FACS purified using the procedure described above.

Cells within the same light scatter-gated strip of events as in the previous experiment were separated according to their degree of immunolabeling with the neuronal marker NeuN and the neural activation marker β-gal. In tissue obtained from cocaine-injected rats, ∼10% of NeuN-labeled neurons had high levels of β-gal (Fig. 6), which corresponded to ∼60,000 β-gal-labeled neurons per rat. All β-gal-labeled cells coexpressed NeuN, indicating that only neurons expressed β-gal. Again, tissue obtained from rats injected with saline on test day produced very few β-gal- or Fos-expressing neurons, and thus not enough cells for subsequent molecular analyses. Therefore, we used only NeuN labeling to separate neuronal from non-neuronal cells obtained from saline-injected rats. Approximately 30% of all cell bodies in saline-injected rats were NeuN positive, which in this experiment corresponded to ∼400,000 striatal neurons per rat.

Figure 6.

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting of β-gal-labeled neurons from sensitized rats challenged with cocaine 7 d after repeated cocaine treatment. Fluorescence plot in which each dot represents one event. NeuN labels all neurons; β-galactosidase labels activated neurons. Two collection gates (solid line boxes) encompass activated and nonactivated neurons that were collected for further analysis.

We used qPCR to compare gene expression in β-gal-positive and β-gal-negative neurons from cocaine-injected rats as well as all NeuN-positive neurons from saline-injected rats following cocaine sensitization. β-gal-positive neurons from cocaine-injected rats expressed higher levels of three neural activity marker genes— fosB, arc, and nr4a3—relative to β-gal-negative neurons from the same cocaine-injected rats and to all neurons from saline-injected rats (Fig. 7a; data and statistical information in Table 3). β-gal-positive neurons also expressed a higher level of the prodynorphin gene similar to that in the single cocaine injection experiment (Fig. 7b). In contrast, β-gal-positive neurons had lower levels of expression for several genes (Fig. 7c), including Drd2 encoding the D2 dopamine receptor, and Map2k6 encoding the kinase that activates p38 MAPK, similar to the single acute cocaine injection experiment. Finally, β-gal-positive neurons had increased expression of dusp1, also known as mkp1 (Fig. 7c), which encodes the phosphatase that inactivates p38 MAPK (Sgambato et al., 1998).

Figure 7.

Quantitative PCR demonstrates a gene expression profile in β-gal-positive neurons from sensitized cocaine-challenged rats different from that of β-gal-negative neurons from the same rats, or of all neurons from saline-challenged rats. a, mRNA levels for the immediate early genes arc, fosB, and nr4a3 are increased in β-gal-positive neurons. b, mRNA levels for the D1-type cell marker prodynorphin (pdyn) are increased in β-gal-positive neurons, while the D2 receptor drd2 is decreased in β-gal-positive neurons. c, mRNA levels for the kinase that activates p38 MAPK (map2k6) are decreased in β-gal-positive neurons, while mRNA levels for the phosphatase that inactivates p38 MAPK (mkp1 or dusp1) are increased in β-gal-positive neurons. n = 3 for every sample. See Table 3 for p values. *p < 0.05 versus NeuN-positive neurons from saline-injected rats. †p < 0.05 versus β-gal-negative neurons from cocaine-injected rats.

Table 3.

Summary of qPCR data from the repeated cocaine experiment

| Gene symbol | Description | Gene ID | Quantitative PCR |

|---|---|---|---|

| FosB | fra-2; FBJ osteosarcoma oncogene B; Immediate early gene | 308411 | F(2,5) = 62.652, p < 0.001 |

| β-gal+ vs β-gal−: +6.3-fold; n = 2, 3; p < 0.001 | |||

| β-gal+ vs NeuN+: +10.0-fold; n = 2, 3; p < 0.001 | |||

| β-gal− vs NeuN+: p = 0.478 | |||

| Arc | Activity-regulated cytoskeleton-associated protein | 54323 | F(2,6) = 10.374, p < 0.05 |

| β-gal+ vs β-gal−: +3.5-fold; n = 3, 3; p < 0.01 | |||

| β-gal+ vs NeuN+: +3.0-fold; n = 3, 3; p < 0.01 | |||

| β-gal− vs NeuN+: p = 0.807 | |||

| Nr4a3 | Nuclear receptor subfamily 4, group A, member 3; transcription factor | 58853 | F(2,6) = 43.423, p < 0.001 |

| β-gal+ vs β-gal−: +6.5-fold; n = 3, 3; p < 0.001 | |||

| β-gal+ vs NeuN+: +6.5-fold; n = 3, 3; p < 0.001 | |||

| β-gal− vs NeuN+: p = 1.000 | |||

| Pdyn | Prodynorphin; peptide found in D1-expressing striatal neurons | 29190 | F(2,6) = 20.757, p < 0.005 |

| β-gal+ vs β-gal−: +3.8-fold; n = 3, 3; p < 0.005 | |||

| β-gal+ vs NeuN+: +3.2-fold; n = 3, 3; p < 0.005 | |||

| β-gal− vs NeuN+: p = 0.716 | |||

| Drd2 | Dopamine receptor D2 | 24318 | F(2,6) = 14.389, p < 0.01 |

| β-gal+ vs β-gal−: −2.9-fold; n = 3, 3; p < 0.005 | |||

| β-gal+ vs NeuN+: −2.8-fold; n = 3, 3; p < 0.005 | |||

| β-gal− vs NeuN+: p = 0.874 | |||

| Adora2a | Adenosine A2a receptor; found in D2-expressing striatal neurons | 25369 | F(2,6) = 3.963, p = 0.080 |

| β-gal+ vs β-gal−: −2.9-fold; n = 3, 3; p = 0.190 | |||

| β-gal+ vs NeuN+: −4.6-fold; n = 3, 3; p < 0.05 | |||

| β-gal− vs NeuN+: p = 0.230 | |||

| Kcnc1 | Kv4; Kv3.1; Potassium voltage-gated channel, Shaw-related subfamily, member 1 | 25327 | F(2,6) = 2.704, p = 0.145 |

| β-gal+ vs β-gal−: p = 0.10 | |||

| β-gal+ vs NeuN+: p = 0.09 | |||

| β-gal− vs NeuN+: p = 0.941 | |||

| Map2k6 | Mkk6; Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 6; activator of p38 MAPK | 114495 | F(2,6) = 38.591, p < 0.001 |

| β-gal+ vs β-gal−: −8.5-fold; n = 3, 3; p < 0.001 | |||

| β-gal+ vs NeuN+: −7.3-fold; n = 3, 3; p < 0.001 | |||

| β-gal− vs NeuN+: p = 0.239 | |||

| Mkp1 | Mkp1; Dual specificity phosphatase 1; dephosphorylates and inactivates p38 MAPK | 114856 | F(2,6) = 7.600, p < 0.05 |

| β-gal+ vs β-gal−: +1.3-fold; n = 3, 3; p < 0.05 | |||

| β-gal+ vs NeuN+: +1.6-fold; n = 3, 3; p < 0.01 | |||

| β-gal− vs NeuN+: p = 0.219 |

One-way ANOVA (F and p values are shown in Quantitative PCR column) was used to compare gene expression in three groups of cells: β-gal-positive neurons and β-gal-negative neurons from the same sensitized rats that received an injection of cocaine 90 min before obtaining tissue, and all neurons (NeuN-positive; NeuN+) from sensitized rats that received an injection of saline 90 min before obtaining tissue. Fold-level changes are relative to control levels in NeuN + cells. Positive fold-level changes indicate higher levels, while negative fold-level changes indicate lower levels, than in NeuN + control samples.

To determine whether mRNA alterations in activated neurons are reflected at the protein level, we used immunohistochemical analysis of coronal brain sections from wild-type cocaine-sensitized female rats following either cocaine or saline injections on test day. In ventral striatum from cocaine-injected rats, the neural activity markers Fos and Arc were coexpressed in the same cells: 90 ± 2% of all Fos-positive cells were Arc positive, and 83 ± 2% of all Arc-positive cells were Fos positive. Cocaine test injections produced a 2.3-fold increase in Fos-labeled neurons and a 2.2-fold increase in Arc-labeled neurons. In dorsal striatum from cocaine-injected rats, 93 ± 2% of all Fos-positive cells were Arc positive, and 90 ± 3% of all Arc-positive cells were Fos positive. Cocaine test injections produced a 4.4-fold increase in Fos-labeled neurons and a 4.5-fold increase in Arc-labeled neurons. Thus, very few non-Fos-labeled cells expressed Arc and very few non-Arc-labeled cells expressed Fos, which supports our findings from sorted cells.

Discussion

We developed a procedure for purifying and assessing molecular alterations within neurons defined only by their previous activation state during cocaine-induced locomotor activity. Data from the microarray, qPCR, and immunohistochemistry experiments independently confirmed that our FACS procedure identified unique molecular alterations within activated neurons, as defined by c-fos promoter induction of β-gal expression. The main biological finding using this procedure was that immediate early genes (IEGs) are induced only in activated neurons, whereas IEG expression is unchanged or even decreased in the nonactivated majority of neurons. Since many of these IEG neural activity markers are also transcription factors, it is likely that very different patterns of gene expression are subsequently induced within these activated neurons that may contribute to the physiological and behavioral effects of cocaine [for example, see Curran and Franza (1988), Nestler et al. (1993), McClung et al. (2004), and Loebrich and Nedivi (2009)].

Differential IEG induction between activated and nonactivated neurons supports the hypothesis that only a minority of neurons are strongly activated during cocaine-induced locomotion, while the majority of neurons are activated to a far lesser degree or not at all. Electrophysiological experiments in wild-type rats indicate that Fos protein expression correlates with high levels of excitatory synaptic input (Shin et al., 1990; Labiner et al., 1993; Sgambato et al., 1997). We know that Fos and β-gal expression are similarly regulated in the same neurons in cfos-lacZ rats (Koya et al., 2009). Thus, we infer that increased β-gal and IEG expression in only a small number of striatal neurons indicates that only a minority of striatal neurons receives high levels of excitatory synaptic input in response to cocaine administration.

Discrete activation of striatal neurons is consistent with the up state–down state hypothesis, which describes opposing effects of dopamine on striatal neuronal activity. Cocaine-induced dopamine is thought to enhance differences between high-activity and low-activity neurons by enhancing ongoing electrophysiological activity of neurons that are already in a high-activity state, while attenuating ongoing activity of the majority of neurons with lower activity (Wilson and Kawaguchi, 1996; Hernández-López et al., 1997; Nicola et al., 2000; O'Donnell, 2003; Nicola et al., 2004). The resulting increase in signal-to-noise ratio not only enhances selectivity during acute signaling but, as suggested in our study, may also contribute to induction of unique molecular neuroadaptations in only the high-activity neurons. Meanwhile gene expression in β-gal-negative neurons, which compose the majority of striatal neurons from cocaine-injected rats, appeared to be no different from gene expression in striatal neurons from saline-injected rats; this supports the hypothesis that the majority of striatal neurons remain in the down state during cocaine exposure.

Components of the p38 MAP kinase signaling pathway were also differentially altered between activated and nonactivated neurons. Gene expression of Map2k6/MEKK6, a kinase that activates p38, was decreased, while gene expression of Mkp1/Dusp1, a phosphatase that inactivates p38 (Sgambato et al., 1998), was increased in activated neurons but not in nonactivated neurons. Thus overall p38 MAPK signaling, shown to be play a role in synaptic plasticity (Bolshakov et al., 2000; Izumi et al., 2008), may be attenuated in activated neurons relative to the nonactivated majority of neurons.

FACS can also help identify the neuronal types that are activated after acute or repeated cocaine exposure. We found higher expression of the D1 neuronal marker gene prodynorphin in activated neurons, and lower expression of the D2 neuronal marker genes D2 dopamine receptor and A2A adenosine receptor in activated neurons. This suggests that Fos was induced primarily in D1 striatal neurons. While this agrees with many immunohistochemical studies that report Fos induction primarily in D1 neurons following psychostimulant injections in the home cage (Berretta et al., 1992; Cenci et al., 1992), it contradicts the equal activation of D1 and D2 neurons found following psychostimulant injections in a relatively novel environment outside the rat's home cage (Jaber et al., 1995; Badiani et al., 1999; Hope et al., 2006).

Since we used the same β-gal marker to identify activated neurons during FACS as we used for our previously described Daun02 inactivation procedure (Koya et al., 2009), it is plausible that we are observing unique molecular alterations within neuronal ensembles necessary for the learned component of context-specific sensitization of cocaine-induced locomotion. We previously found that inactivation of only a small number of sparsely distributed neurons within a putative ensemble is sufficient to disrupt context-specific cocaine psychomotor sensitization (Koya et al., 2009). This finding was replicated using the same female cfos-lacZ rats and sensitization regimen used in the present study (see Notes). These neurons are not inherently more sensitive to all stimuli, since altering the environment or context where drug was administered activated a different set of striatal neurons following cocaine injections (Mattson et al., 2008; Koya et al., 2009). Selection of a specific striatal neuronal ensemble appears primarily dependent on the pattern of activity from cortical and subcortical glutamatergic afferents (Pennartz et al., 1994; O'Donnell, 2003), and these inputs are themselves determined by specific environmental and interoceptive stimuli present during behavior. From this previous work along with our present data, we hypothesize that repeated pairing of cocaine with environmental stimuli during our sensitization regimen produces unique molecular alterations within repeatedly activated neuronal ensembles that may contribute to the learned associations underlying context-specific sensitization.

Overall, we demonstrated a novel application of FACS to isolate adult neurons selectively activated during acute cocaine-induced locomotor activity and repeated cocaine-induced locomotor sensitization. We propose that this approach could also be used to identify unique molecular neuroadaptations in neuronal ensembles encoding the behavioral effects of abused drugs and other learned behaviors. The causal roles of these unique molecular neuroadaptations in neural plasticity and behavior must eventually be examined by manipulating gene expression in only activated neurons; however, this technique has yet to be developed.

Notes

Supplemental material for this article is available at http://irp.drugabuse.gov/BNRB.html. This material shows that Daun02 inactivates selectively activated nucleus accumbens neurons and attenuates cocaine-sensitized locomotion. This material has not been peer reviewed.

Footnotes

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Drug Abuse. D.G.-B. was supported by National Institutes of Health Medical Scientist Training Program TG 5T32GM07205, Award Number F30DA024931 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, and the Charles B. G. Murphy Chair in Psychiatry at Yale University. We thank Joe Chrest for his excellent technical assistance with FACS, and Chris Cheadle, Tonya Watkins, and Alan Berger for their work on the microarray. We thank Yavin Shaham for helpful comments on the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Badiani A, Oates MM, Day HE, Watson SJ, Akil H, Robinson TE. Environmental modulation of amphetamine-induced c-fos expression in D1 versus D2 striatal neurons. Behav Brain Res. 1999;103:203–209. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(99)00041-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berretta S, Robertson HA, Graybiel AM. Dopamine and glutamate agonists stimulate neuron-specific expression of Fos-like protein in the striatum. J Neurophysiol. 1992;68:767–777. doi: 10.1152/jn.1992.68.3.767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolshakov VY, Carboni L, Cobb MH, Siegelbaum SA, Belardetti F. Dual MAP kinase pathways mediate opposing forms of long-term plasticity at CA3-CA1 synapses. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3:1107–1112. doi: 10.1038/80624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowers MS, Chen BT, Bonci A. AMPA receptor synaptic plasticity induced by psychostimulants: the past, present, and therapeutic future. Neuron. 2010;67:11–24. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cenci MA, Campbell K, Wictorin K, Björklund A. Striatal c-fos induction by cocaine or apomorphine occurs preferentially in output neurons projecting to the substantia nigra in the rat. Eur J Neurosci. 1992;4:376–380. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1992.tb00885.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran T, Franza BR., Jr Fos and Jun: the AP-1 connection. Cell. 1988;55:395–397. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90024-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garg S, Nichols JR, Esen N, Liu S, Phulwani NK, Syed MM, Wood WH, Zhang Y, Becker KG, Aldrich A, Kielian T. MyD88 expression by CNS-resident cells is pivotal for eliciting protective immunity in brain abscesses. ASN Neuro. 2009;1:e00007. doi: 10.1042/AN20090004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerfen CR, Keefe KA, Gauda EB. D1 and D2 dopamine receptor function in the striatum: coactivation of D1- and D2-dopamine receptors on separate populations of neurons results in potentiated immediate early gene response in D1-containing neurons. J Neurosci. 1995;15:8167–8176. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-12-08167.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzowski JF, Timlin JA, Roysam B, McNaughton BL, Worley PF, Barnes CA. Mapping behaviorally relevant neural circuits with immediate-early gene expression. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2005;15:599–606. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2005.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-López S, Bargas J, Surmeier DJ, Reyes A, Galarraga E. D1 receptor activation enhances evoked discharge in neostriatal medium spiny neurons by modulating an L-type Ca2+ conductance. J Neurosci. 1997;17:3334–3342. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-09-03334.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hope BT, Simmons DE, Mitchell TB, Kreuter JD, Mattson BJ. Cocaine-induced locomotor activity and Fos expression in nucleus accumbens are sensitized for 6 months after repeated cocaine administration outside the home cage. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;24:867–875. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04969.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izumi Y, Tokuda K, Zorumski CF. Long-term potentiation inhibition by low-level N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor activation involves calcineurin, nitric oxide, and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase. Hippocampus. 2008;18:258–265. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaber M, Cador M, Dumartin B, Normand E, Stinus L, Bloch B. Acute and chronic amphetamine treatments differently regulate neuropeptide messenger RNA levels and Fos immunoreactivity in rat striatal neurons. Neuroscience. 1995;65:1041–1050. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)00537-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalivas PW. The glutamate homeostasis hypothesis of addiction. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10:561–572. doi: 10.1038/nrn2515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasof GM, Mahanty NK, Pozzo Miller LD, Curran T, Connor JA, Morgan JI. Spontaneous and evoked glutamate signalling influences Fos-lacZ expression and pyramidal cell death in hippocampal slice cultures from transgenic rats. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1995;34:197–208. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(95)00158-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koya E, Golden SA, Harvey BK, Guez-Barber DH, Berkow A, Simmons DE, Bossert JM, Nair SG, Uejima JL, Marin MT, Mitchell TB, Farquhar D, Ghosh SC, Mattson BJ, Hope BT. Targeted disruption of cocaine-activated nucleus accumbens neurons prevents context-specific sensitization. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:1069–1073. doi: 10.1038/nn.2364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon B, Houpt TA. A combined method of laser capture microdissection and X-Gal histology to analyze gene expression in c-Fos-specific neurons. J Neurosci Methods. 2010;186:155–164. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2009.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labiner DM, Butler LS, Cao Z, Hosford DA, Shin C, McNamara JO. Induction of c-fos mRNA by kindled seizures: complex relationship with neuronal burst firing. J Neurosci. 1993;13:744–751. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-02-00744.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberles SD, Buck LB. A second class of chemosensory receptors in the olfactory epithelium. Nature. 2006;442:645–650. doi: 10.1038/nature05066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobo MK, Karsten SL, Gray M, Geschwind DH, Yang XW. FACS-array profiling of striatal projection neuron subtypes in juvenile and adult mouse brains. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:443–452. doi: 10.1038/nn1654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loebrich S, Nedivi E. The function of activity-regulated genes in the nervous system. Physiol Rev. 2009;89:1079–1103. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00013.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattson BJ, Koya E, Simmons DE, Mitchell TB, Berkow A, Crombag HS, Hope BT. Context-specific sensitization of cocaine-induced locomotor activity and associated neuronal ensembles in rat nucleus accumbens. Eur J Neurosci. 2008;27:202–212. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05984.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClung CA, Ulery PG, Perrotti LI, Zachariou V, Berton O, Nestler EJ. DeltaFosB: a molecular switch for long-term adaptation in the brain. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2004;132:146–154. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2004.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nestler EJ. Molecular basis of long-term plasticity underlying addiction. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2:119–128. doi: 10.1038/35053570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nestler EJ, Hope BT, Widnell KL. Drug-addiction—a model for the molecular basis of neural plasticity. Neuron. 1993;11:995–1006. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90213-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicola SM, Surmeier J, Malenka RC. Dopaminergic modulation of neuronal excitability in the striatum and nucleus accumbens. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2000;23:185–215. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.23.1.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicola SM, Hopf FW, Hjelmstad GO. Contrast enhancement: a physiological effect of striatal dopamine? Cell Tissue Res. 2004;318:93–106. doi: 10.1007/s00441-004-0929-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Donnell P. Dopamine gating of forebrain neural ensembles. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;17:429–435. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02463.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C. The rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates. Ed 4. San Diego: Academic; 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennartz CM, Groenewegen HJ, Lopes da Silva FH. The nucleus accumbens as a complex of functionally distinct neuronal ensembles: an integration of behavioural, electrophysiological and anatomical data. Prog Neurobiol. 1994;42:719–761. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(94)90025-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters RV, Aronin N, Schwartz WJ. c-Fos expression in the rat intergeniculate leaflet: photic regulation, co-localization with Fos-B, and cellular identification. Brain Res. 1996;728:231–241. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(96)00414-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sgambato V, Abo V, Rogard M, Besson MJ, Deniau JM. Effect of electrical stimulation of the cerebral cortex on the expression of the Fos protein in the basal ganglia. Neuroscience. 1997;81:93–112. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00179-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sgambato V, Pagès C, Rogard M, Besson MJ, Caboche J. Extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) controls immediate early gene induction on corticostriatal stimulation. J Neurosci. 1998;18:8814–8825. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-21-08814.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaham Y, Hope BT. The role of neuroadaptations in relapse to drug seeking. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:1437–1439. doi: 10.1038/nn1105-1437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin C, McNamara JO, Morgan JI, Curran T, Cohen DR. Induction of c-fos mRNA expression by afterdischarge in the hippocampus of naive and kindled rats. J Neurochem. 1990;55:1050–1055. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1990.tb04595.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson CJ, Kawaguchi Y. The origins of two-state spontaneous membrane potential fluctuations of neostriatal spiny neurons. J Neurosci. 1996;16:2397–2410. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-07-02397.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf ME, Ferrario CR. AMPA receptor plasticity in the nucleus accumbens after repeated exposure to cocaine. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2010;35:185–211. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]