Summary

The hypothesized variable expression of polymorphic membrane proteins (PmpA-PmpI) in Chlamydia trachomatis-infected patients was tested by examination of the expression of each Pmp subtype in in vitro-grown C. trachomatis. A panel of monospecific polyclonal and monoclonal antibodies was used to demonstrate surface exposure of Pmps of each subtype by differential immunofluorescence (IF) with and without prior detergent permeabilization of paraformaldehyde-fixed inclusions and for selected Pmps by immunogold labeling. Although specific transcript was detected for each pmp gene late in development, IF experiments with Pmp subtype-specific antibodies reveal that a number of inclusions in a single infection do not express Pmps of a given subtype. Co-expression experiments suggest that pmp genes are shut off independently from one another in non-expressing inclusions, i.e. different inclusions are switched off for different Pmps. Overall, these studies establish the existence of an efficient shutoff mechanism independently affecting the expression of each member of the pmp gene family in in vitro-grown C. trachomatis. Like other paralogous gene families of bacterial pathogens, the pmp gene family of C. trachomatis may serve the critical dual function of a highly adaptable virulence factor also providing antigenic diversity in the face of the host adaptive immune response.

Introduction

Members of the Chlamydiaceae infect a wide range of eukaryotic hosts, causing a variety of acute and chronic diseases in both humans and animals (Blanchard and Mabey, 1994). These obligate intracellular pathogens are characterized by a unique developmental cycle consisting of two developmental forms, the infectious extracellular elementary body (EB) and the metabolically active, replicating reticulate body (RB), that takes place entirely within an intracellular vacuole, called an inclusion (Moulder, 1991).

The C. trachomatis genome includes a gene family encoding nine predicted polymorphic membrane proteins (Pmps) (Stephens et al., 1998) named PmpA to PmpI, orthologs of which are found in all other Chlamydia sp. (Thomson et al., 2005; Read et al., 2003; Read et al., 2000; Kalman et al., 1999) (Myers & Bavoil, unpublished). The grouping of the Pmp proteins as a family rests on conserved GGA (I, L,V) and FXXN tetrapeptide motifs that are repeated an average of 7 and 12 times respectively in the amino (N) -proximal segment of each protein. Predicted beta-barrel folding of the carboxy (C) -terminal segment and the presence of a N-terminal sec-dependent leader sequence has suggested (Grimwood and Stephens, 1999) that the Pmps are translocated to the chlamydial surface via type V secretion (autotransport) (Henderson and Lam, 2001), a prediction supported by experimental evidence for several Pmps (Kiselev et al., 2007; Wehrl et al., 2004; Vandahl et al., 2002; Longbottom et al., 1998).

Several roles have been suggested for specific Pmps in chlamydial pathogenesis (Wehrl et al., 2004; Niessner et al., 2003). In particular, PmpD orthologs of C. pneumoniae and C. trachomatis have been shown to function as adhesins in in vitro systems of infection (Crane et al., 2006; Wehrl et al., 2004). Moreover, PmpD as well as other Pmp subtypes of C. trachomatis have recently become leading candidates in the development of a component vaccine against chlamydial infection (Karunakaran et al., 2008; Crane et al., 2006). While various pmp-associated functions in virulence and immunity are emerging, the pmp gene family is paradoxically characterized by an unusual degree of sequence polymorphism including all types of mutation and large indels across Chlamydia sp. (Gomes et al., 2006; Gomes et al., 2004; Rocha et al., 2002; Grimwood et al., 2001; Shirai et al., 2000; Grimwood and Stephens, 1999), suggesting that the pmp gene family is subjected to high selective pressure (e.g. host-specific or immune) which drives a relatively faster evolutionary rate for these antigens.

Studies of pmp gene expression have yielded inconsistent results. RT-PCR analysis indicates that all pmp genes are transcribed in C. trachomatis (Nunes et al., 2007; Lindquist and Stephens, 1998) and C. pneumoniae (Grimwood et al., 2001) grown in vitro. However, only ten of 21 possible C. pneumoniae Pmps (Grimwood et al., 2001; Vandahl et al., 2001) and six of 24 possible C. psittaci Pmps (Tanzer et al., 2001) were detected at the protein level. Skipp et al (Skipp et al., 2005) detected expression of all nine Pmps of C. trachomatis serovar L2/434 by proteomic analysis, but other researchers detected only six Pmps (B, D, E, F, G and H) from the same serovar and other serovars (Shaw et al., 2002; Tanzer et al., 2001; Mygind et al., 2000). Finally, differential expression of selected Pmps of C. pneumoniae has been observed both in tissue culture and in infected animals (Pedersen et al., 2001; Birkelund et al., 1998). Consistent with the observed variable expression of pmp genes in various Chlamydia sp., we have recently documented variable Pmp-specific antibody profiles in four distinct C. trachomatis-infected patient groups (Tan et al., 2009), which we hypothesize may be consequent to variable pmp expression in the infecting chlamydiae. In this study, we show that although all nine pmp genes are transcribed in in vitro-grown C. trachomatis, production of the surface-exposed Pmp proteins is subject to high frequency on/off switching at the inclusion level by a mechanism phenotypically resembling phase variation.

Results

All pmp genes are transcribed in in vitro grown C. trachomatis

We first investigated the possible variation of pmp gene expression at the transcriptional level in C. trachomatis reference strains of serovars D, E and L2. All nine pmp gene transcripts could be detected in total RNA isolated from Hela 229 cultures infected with strains of each of the three serovars at 42 hours post-infection (hpi) (Fig. 1). This is consistent with results by other investigators using the same or different C. trachomatis strains (Kiselev et al., 2007; Nunes et al., 2007; Lindquist and Stephens, 1998). All subsequent experiments were performed using in vitro-grown C. trachomatis serovar E at 42 hpi.

Figure 1.

All nine pmp genes are transcribed in in vitro-grown C. trachomatis. Total RNA from C. trachomatis serovar D/UW3, E/ UW5-CX, and L2/434-infected Hela 229 cells (42 hpi) was subjected to two-step RT-PCR and the PCR products visualized on a 1% agarose gel. +/−: RT and no-RT groups. Lane 1, DNA ladder. Lanes 2–21, RT-PCR products of 16S rRNA and nine pmp genes are all within the range of 350–550 bp.

Generation of Pmp subtype-specific antibodies

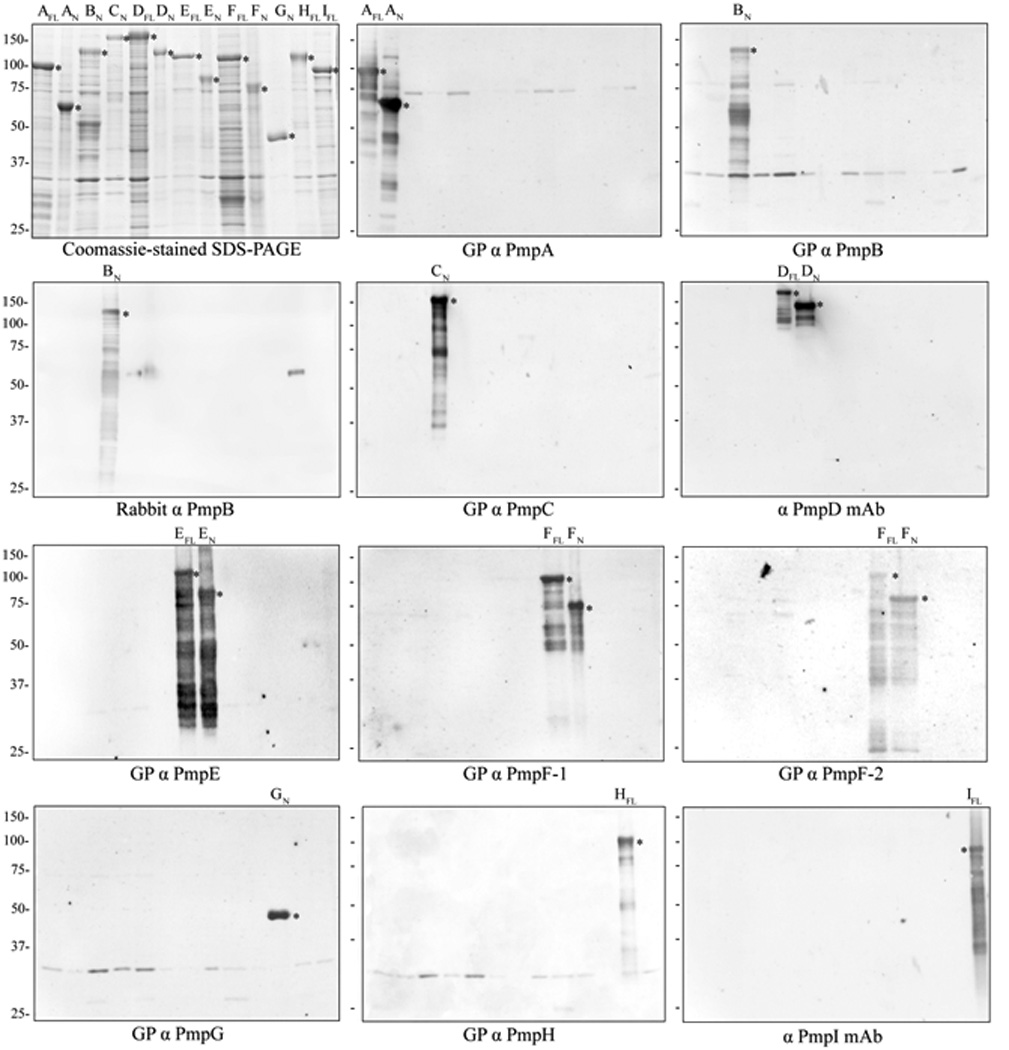

To investigate the possibility of pmp variable expression at the protein level, a complete panel of Pmp-specific antibodies, including monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) against PmpD and I, guinea pig monospecific polyclonal antibodies (pAbs) against PmpA, B, C, E, F, G and H, and rabbit monospecific pAb against PmpB, was generated. Specificity of the extensively adsorbed Ab toward a given immunizing rPmp subtype was confirmed by immunoblot against a complete panel of rPmps (Fig. 2) whereby each antibody reacted specifically with the full length and/or the N-terminal fragment of the immunizing antigen and did not cross-react with any other rPmp subtype. Two distinct anti-PmpF pAbs (anti-PmpF-1 and −2) were generated that displayed different immune reactivity to the full-length and N-terminal fragment of rPmpF (rPmpF-FL and rPmpF-N). Reactive bands that remained post adsorption of the pAbs were conserved in several lanes indicating that they most likely consist of E. coli contaminants present in the insoluble inclusion bodies. Importantly, all antibodies reacted specifically with high molecular weight (Mw) polypeptides present in lysates of purified C. trachomatis EBs by immunoblot analysis (Fig. 3) and with C. trachomatis inclusions (see below) by immunofluorescence (IF) microscopy. Antibodies specific for PmpD, E, F, G and H detected bands with apparent Mw equal or close to the calculated Mw of full-length Pmp proteins in purified EB lysates. Additional lower Mw bands detected for PmpB, C, D, E, F, G and I likely represent processed or degraded Pmp fragments. In general, a good correlation was also observed between the apparent Mw of EB Pmp-antibody reactive bands and those detected by proteomic analysis in serovars A, D and L2 (Shaw et al., 2002) (Fig. 3), with near exact matches for fragments of PmpF (70 vs. 71.5 kDa), PmpG (100 vs. 103.3–107.3 Kda) and PmpH (100 vs. 102.4–103.1 kDa) and relatively small differences for PmpB (25 vs. 32.5 kDa) and PmpD (100 vs. 87.3 kDa). PmpA was detected as a single band of apparent Mw 70 kDa by immunoblot, i.e. significantly smaller that the calculated Mw, suggesting that PmpA is proteolytically processed upon translocation.

Figure 2.

Immunoblot of rPmps with a complete panel of anti-Pmp antibodies. Partially purified rPmpA-I full-length protein (FL) and/or N-terminal fragment (N) were fractionated by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie blue-stained, or immunoblotted with eleven anti-Pmp antibodies as indicated. Asterisks indicate specific reactivity against individual rPmps. The calculated Mw’s (kDa) of the rPmps are: 107.8/AFL, 65.9/AN, 101.6/BN, 108.3/CN, 164.3/DFL, 142/DN, 112.1/EFL, 80.6/EN, 116.3/FFL, 79.3/FN, 43.1/GN, 110.8/HFL and 97.7/IFL (Tan et al., 2009). GP: guinea pig.

Figure 3.

Purified chlamydiae express immunoreactive proteins detected by Pmp-specific antibodies. EB: stained gel of EB proteins. A–I: purified C. trachomatis serovar E EB proteins immunoblotted against each of the guinea pig polyclonal or mouse monoclonal Pmp-specific antibodies. The calculated and observed Mw of the major protein bands are shown below the blot (major bands are underlined).

All Pmps are translocated to the surface of intracellular chlamydiae

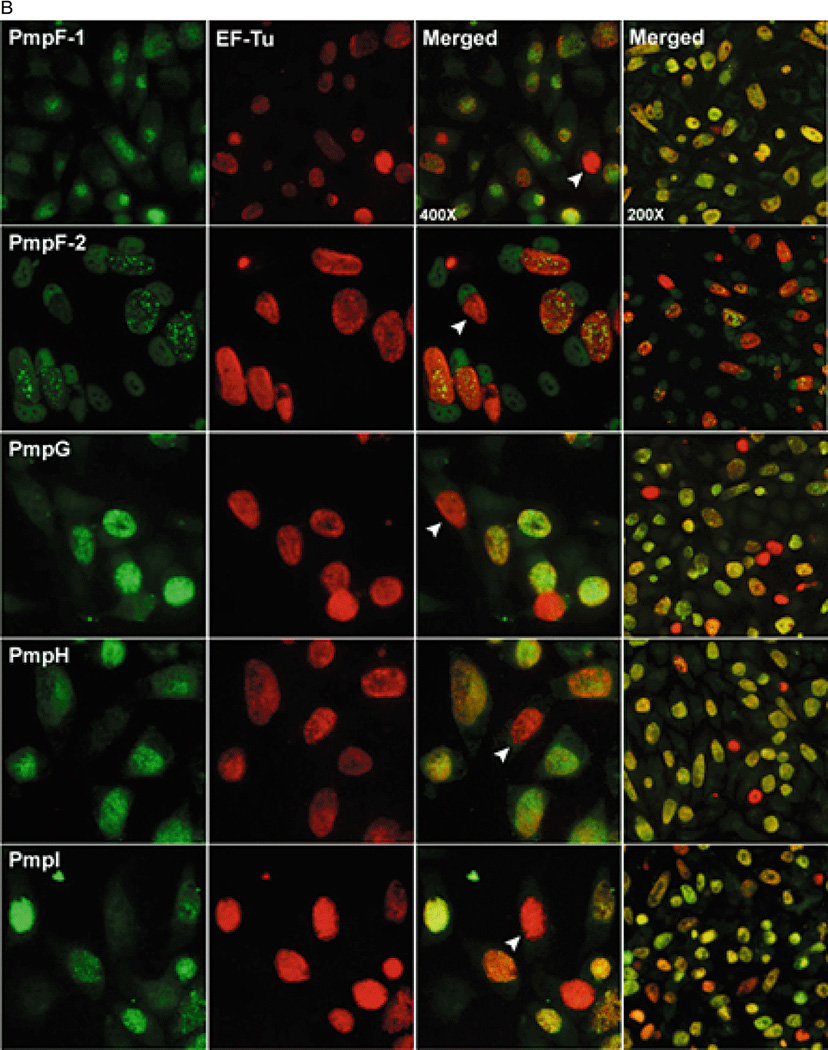

In silico analysis has predicted that Pmps are autotransported proteins consistent with the observed surface localization of several Pmp proteins in various Chlamydia species (Kiselev et al., 2007; Wehrl et al., 2004; Vandahl et al., 2002; Longbottom et al., 1998). We therefore tested whether Pmps of C. trachomatis are immuno accessible at the surface of late intracellular chlamydiae (42 hpi) using a method similar to that developed by Vandahl et al (Vandahl et al., 2002). In this method, antibody binding to surface-exposed antigens in paraformaldehyde (PFA)-fixed C. trachomatis-infected Hela cells does not require prior permeabilization with Triton X-100 (Kiselev et al., 2007; Wehrl et al., 2004; Vandahl et al., 2002; Longbottom et al., 1998). Antibody binding to non-surface exposed antigens such as cytoplasmic proteins does however require prior permeabilization of the PFA-fixed monolayer with Triton X-100. Results show that the cytoplasmic protein elongation factor Tu (EF-Tu) was only accessible to antibody with prior Triton X-100 permeabilization (Fig. 4A), while the surface-exposed MOMP (Fig. 4A) and all Pmps (Fig. 4B) were accessible to specific antibodies without prior permeabilization with the detergent. Immunogold labeling of chlamydiae with antibodies specific for PmpB, D and I further confirmed the surface localization of these Pmps (Fig. 5). These results demonstrate that all nine Pmps are expressed and translocated to the surface of late intracellular chlamydiae.

Figure 4.

All nine Pmps of C. trachomatis serovar E are surface-exposed. Infected Hela cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at 42 hpi, and optionally permeabilized using 0.1% Triton X-100 as indicated. Monolayers were stained with EF-Tu-specific mAb, rabbit MOMP-specific pAb (A), guinea pig Pmp-specific pAb or murine Pmp-specific mAb (B) and Alexa 488 conjugated secondary antibodies (green) and counterstained with Alexa 546 conjugated Phalloidin (red). Images were examined at 400× magnification.

Figure 5.

Immuno-electron microscopy of purified C. trachomatis serovar E. Purified chlamydiae of serovar E were adsorbed onto formva-coated grids, labelled with rabbit MOMP-specific pAb, guinea pig PmpB-specific pAb or murine PmpD/I-specific mAbs as indicated and gold-conjugated secondary antibodies, negatively stained with 1% PTA, and imaged by TEM.

Pmp antigen expression is subject to high frequency shutoff in in vitro cultured C. trachomatis

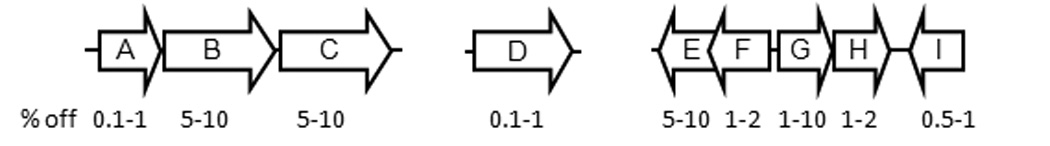

Although all nine pmp genes are transcribed and the Pmp proteins are produced, these results do not address the possible variation of expression at the level of single chlamydiae or individual inclusions within a culture. To answer this question, we double-stained infected Hela cell cultures using primary antibodies specific for each individual Pmp subtype and for the constitutively expressed EF-Tu. Three distinct phenotypes are simultaneously identifiable for the expression of a given Pmp subtype within a single culture: a majority of “fully-on” inclusions (orange in merged images) within which all chlamydiae appeared to express the given Pmp at a high level, relatively few “fully-off” inclusions (red in merged images) within which all chlamydiae appeared not to express a given Pmp, and a variable number of inclusions that appeared to express at an intermediate level (Fig. 6). The basis for the presence of intermediate level inclusions is unclear as pmp expression may be modulated by multiple regulatory mechanisms independent of the apparent shutoff mechanism observed here (e.g. developmental regulation). Hence in the following sections, fully-on and intermediate inclusions are lumped together while non-expressing inclusions refer strictly to fully-off inclusions. The percentage of non-expressing inclusions varied for different Pmp subtypes, ranging from below 1% for PmpA, D and I, 1–2% for PmpF and H, to 5–10% for PmpB, C and E (Fig. 7). Different off frequencies were observed uniquely for PmpG in different experiments conducted under the same infection conditions. In one experiment, PmpG-non expressing inclusions represented more than 10% of all inclusions. In another, the frequency of PmpG-non expressing inclusions was near 1%. Interestingly, two different anti-PmpF pAbs yielded distinct staining patterns by IF (Fig. 6). Anti-PmpF-1 pAb stained PmpF homogeneously in PmpF-expressing inclusions similar to the antibodies specific for other Pmps. In contrast, anti-PmpF-2 pAb yielded a characteristic punctate staining where not all chlamydiae within the inclusion were recognized in PmpF-expressing inclusions. However, staining of inclusions with either pAb yielded PmpF-non expressing inclusions with equal frequencies.

Figure 6.

ab: Variable expression of the nine Pmps in in vitro-grown C. trachomatis serovar E. Infected Hela cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at 42 hpi, double-stained with PmpA/B/C/E/F/G/H-specific guinea pig pAb or PmpD/I-specific murine mAb (left-most column) and anti-EF-Tu mAb (second column from the left), and visualized at 400× magnification. Merged images are shown in the third column. For a visual estimate of the frequency of individual Pmp off phenotypes, 200× magnified merged images are shown in the right-most column. White arrows indicate Pmp-negative inclusions.

Figure 7.

Relative frequencies of Pmp “off” inclusions in in vitro grown C. trachomatis serovar E. The percent range derived from a minimum of three experiments for each Pmp subtype is shown in relationship to the conserved pmp gene organization in C. trachomatis.

Expression of PmpB varies independently from that of PmpC, E, G and H

Given the capacity of inclusions for variable expression of each Pmp subtype, an important question is whether the nine Pmp subtypes are switched on or off independently from one another in a given inclusion or coordinately, e.g. in an all-or-none manner. Although it is not possible to answer this question comprehensively in view of the multitude of possible Pmp subtype combinations, we performed limited co-expression studies using Pmp subtypes expressed from the two major unlinked pmp loci pmpA-C and pmpE-I. In these experiments, rabbit pAb specific for PmpB and guinea pig pAbs specific for the genetically linked PmpC or the unlinked PmpE, G or H were used to double stain late C. trachomatis-infected Hela cells (42 hpi). Results indicate that PmpC-, G- and H- non expressing inclusions can be readily identified among PmpB-expressing inclusions (Fig. 8). Conversely, PmpB-non expressing inclusions were present among PmpC-, E- and G-expressing inclusions. Most inclusions expressed both PmpB and the heterologous Pmp subtype (orange in merged images) with only a few inclusions expressing either one or the other (green or red in merged images), with off frequencies consistent with those already observed in IF experiments with individual Pmps.

Figure 8.

Co-expression of Pmp proteins in in vitro grown C. trachomatis serovar E. Infected Hela cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at 42 hpi, double-stained with rabbit anti-PmpB pAb (middle column) and Pmp-specific guinea pig pAb as indicated (left column) followed by animal-specific Alexa fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibodies, and visualized at 400× magnification. Merged images are shown in the column on the right. White arrows indicate inclusions that are positive for only one Pmp among the double-stained inclusions.

Discussion

We have previously observed that patients with C. trachomatis genital infection display varied antibody profiles against individual or multiple Pmps (Tan et al., 2009) suggesting that these proteins are likely variably expressed by infecting chlamydiae. In this study, we now characterize the expression properties of the complete nine-member pmp gene family in individual inclusions in in vitro-grown C. trachomatis.

We first examined the transcription of the nine pmp genes in cultures of C. trachomatis serovar D, E, and L2 reference strains at the late developmental time of 42 hpi, when a majority of the chlamydiae contained within the inclusion are fully differentiated to infectious EBs. Results indicate that the nine pmp genes are transcribed in the three tested C. trachomatis strains (Fig. 1), consistent with other studies (Kiselev et al., 2007; Nunes et al., 2007; Lindquist and Stephens, 1998). To further investigate pmp gene expression at the protein level, a complete panel of antibodies specific for each of the nine Pmp subtypes of C. trachomatis serovar E was generated. Most antibodies recognized multiple polypeptide bands in lysates of purified EBs by immunoblot, including fragments similar in size to the full-length Pmp polypeptides as well as lower Mw bands likely resulting from proteolytic processing during autotransport (Fig. 3). In general, the sizes of Pmp antigens expressed in C. trachomatis serovar E EBs were consistent with either the calculated Mw for the full-length protein or with the Mw of fragments resulting from Pmp processing (Swanson et al., 2009; Kiselev et al., 2007; Shaw et al., 2002; Vandahl et al., 2002) or both. Overall, our results indicate that each antibody recognizes mutually exclusive epitopes on each Pmp subtype and as such is suitable for further investigation of the expressed native Pmps in chlamydial inclusions.

The antibodies were first used to investigate the subcellular localization of Pmp proteins of each subtype by IF microscopy of C. trachomatis serovar E-infected Hela monolayers using differential Triton X-100 permeabilization. In these experiments, each Pmp subtype was accessible to antibody in whole inclusions (42 hpi) without prior detergent permeabilization demonstrating surface exposure (Fig. 4). Surface exposure of selected Pmps (PmpB, D and I) was confirmed by immunogold labeling of isolated EBs (Fig. 5). These results are convergent with studies where surface association of PmpD, E, G, and H of C. trachomatis has been demonstrated (Swanson et al., 2009; Kiselev et al., 2007; Tanzer et al., 2001). Since all antibodies were generated against the N-terminal portion of each Pmp protein, these results indicate that the N-termini of the proteins are surface exposed, further supporting the hypothesis that the Pmp proteins are autotransported to the chlamydial surface. Finally, the finding that all nine Pmps are present on the surface of chlamydial EBs is also consistent with our observation that antibodies are elicited against each Pmp subtype in C. trachomatis infected-patients.

To address the question of variable expression at the level of inclusions, C. trachomatis-infected Hela monolayers (42 hpi) were double stained with antibodies specific for each Pmp subtype and for the constitutively expressed EF-Tu protein (Fig. 6ab). In these experiments, chlamydia-ladden inclusions were reproducibly observed in which expression of a particular Pmp subtype appeared to be uniformly shut off. It should be noted that in the case of PmpD and PmpI, the observed non-expressor inclusion phenotype represents the loss of detection of a single epitope as the expression of these two Pmps was assessed using mAbs, while that of the Pmp subtypes that were detected with pAbs is more likely to represent loss of the whole antigen. Notwithstanding these possible limitations, differences in the off frequency were reproducibly observed for Pmps of different subtypes including for Pmps that are genetically linked (Fig. 7), suggesting that different mechanisms may be responsible for the observed shutoff of pmp expression. For instance, the co-transcribed pmpF and pmpE were phenotypically off in 1–2% and 5–10% of the inclusions respectively (Fig. 7). Although the sequence of the pmpFE operon is highly conserved in different C. trachomatis strains, Nunes et al (2007) observed that pmpF and pmpE transcript levels are dissimilar and speculated that this was due to post-transcriptional processing and/or degradation. Our results are consistent with this interpretation. Interestingly, pmpG uniquely displayed variable off frequencies (ranging from 1 to 10%) in several independent experiments performed under the same infection conditions, suggesting that unique regulatory mechanisms govern pmpG expression. All other pmp on/off ratios however were remarkably conserved between experiments. For example, the relative frequency of pmpA off inclusions consistently represented less than 1% of the inclusions in a single culture. PmpA amino acid sequence is relatively conserved across Chlamydia species, suggesting that PmpA function may also be conserved. Moreover, unlike for other pmp genes, pmpA is not disrupted by mutation in multiple chlamydial isolates and strains regardless of the species, implying a possible in vitro phenotypic advantage for chlamydiae expressing pmpA. The prevalence of PmpA-expressing inclusions in in vitro-grown C. trachomatis also contrasts the relative rarity of PmpA antibodies in C. trachomatis-infected patients who elicit antibody responses most frequently against the PmpB, C, D and I subtypes (Tan et al., 2009). It is however likely that immunogenicity and antigen processing differ for different Pmps or that pmp expression in in vitro–grown laboratory-adapted C. trachomatis differs from that in wild type C. trachomatis during human genital infection. Relatively low off frequencies were also observed for pmpD and pmpI (as low as 1 and 5 in 103, respectively) which unlike PmpA correlates well with the prevalence of PmpD- and PmpI-specific antibodies in C. trachomatis infected patients. Relatively stable production of the conserved PmpD at the EB surface is consistent with its proposed conserved role as an adhesin in C. trachomatis and C. pneumoniae (Crane et al., 2006; Wehrl et al., 2004).

Two anti-PmpF pAbs that reacted differently to rPmpF by immunoblot likewise stained C. trachomatis inclusions distinctly by IF. Both pAbs stained inclusions with an off frequency of 1–2%. However, while anti-PmpF-1 pAB stained inclusions homogeneously similar to the other Pmp-specific pAbs, anti-PmpF-2 pAb yielded a characteristic punctate staining pattern (Fig. 6b, second row from the top), where a significant proportion of the chlamydiae within the inclusion were not stained by the anti-PmpF-2 antibody in otherwise PmpF-expressing inclusions. These results indicate that the two PmpF-specific pAbs most likely detect different epitopes of PmpF and that at least two different antigenic types of PmpF-expressing chlamydiae co-exist within the same PmpF-expressing inclusion.

The experiments described above reveal inclusions that are homogenously positive or negative for Pmp staining late in chlamydial development. This strongly suggests that the Pmp phenotype of an inclusion is predetermined by a specific property of the initial infecting EB. Supporting this interpretation is the observation in the PmpB panel of Fig. 6a (second row from the top), where a single cell is infected simultaneously with a PmpB-expressing inclusion at one pole and a PmpB-non expressing inclusion at the other. Hence, at least for pmpB, expression shutoff is not a response to the metabolic or developmental state of the infected cell. Pending confirmation of similar properties for other Pmps, a corollary of this hypothesis is that pmp expression shutoff is most likely to be determined by a stable trait of the infecting EB that is replicated during growth, e.g. a genotype. To address this hypothesis, we investigated the co-expression properties of selected pmp genes by IF microscopy. Three loci encode Pmp proteins in C. trachomatis, the pmpABC locus, the pmpEFGHI locus and the single pmpD gene (Fig. 7). Genes pmpB and C, and pmpE, G and H from the two multigene loci were chosen for this analysis. The results of these experiments indicate that pmp expression shutoff is not occurring coordinately within an inclusion (Fig. 8). For instance, in spite of similar observed off frequencies (5–10%) for the co-transcribed (Carrasco et al, not shown) pmpB and pmpC genes, PmpB/off-PmpC/on and PmpB/on-PmpC/off inclusions were simultaneously observed in the same culture (Fig. 8). The same held true for Pmps co-expressed from the two different pmp loci. Apart from implications into the mechanism(s) underlying the shutoff of pmp expression, these results also indicate that chlamydiae are likely to always express several Pmps at their surface albeit in various combinations, thereby providing a form of antigenic variation similar to that conferred by the opa gene family of Neisseria gonorrhoeae (Stern and Meyer, 1987). This is consistent with the observation that most C. trachomatis-infected patients have antibodies to several Pmp subtypes simultaneously. This further suggests that the loss of a Pmp subtype at the EB surface may be compensated by the presence of others, i.e. that a degree of functional redundancy exists in this protein family.

A key question becomes that of identifying the actual property of an infecting EB which is responsible for the observed shutoff of pmp expression in a small percentage of the inclusions within a culture. An attractive hypothesis is that pmp expression shutoff is genetically based similar to coupled phase/antigenic variation mechanisms that have been well documented in other systems such as the opacity proteins of Neisseria species (Howell-Adams and Seifert, 2000; Stern and Meyer, 1987; Hagblom et al., 1985), the variable large and small lipoproteins of Borrelia hermsii (Barbour et al., 1982), and the variant surface glycoproteins of Trypanosoma brucei (Donelson, 2003). In these systems, phase variation of the surface antigen is encoded in various reversible rearrangements of the structural genes themselves. Reversibility, an essential trait of a hypothetical phase variation mechanism is difficult to address in a genetically intractable obligate intracellular organism such as Chlamydia. However, a pmp-based phase variation mechanism would predict that a genetic difference(s) should be detected within the population of chlamydiae of a single culture at a frequency similar to that observed for the occurrence of pmp-non expressing inclusions. This hypothesis is particularly attractive as pmp genes are among the most polymorphic known chlamydial genes when compared among Chlamydia isolates and strains (Gomes et al., 2006; Gomes et al., 2004; Rocha et al., 2002; Grimwood et al., 2001; Shirai et al., 2000; Grimwood and Stephens, 1999). To date, preliminary deep genomic sequencing experiments have not revealed non-synonymous variants within the pmp loci within a single culture that could account for a putative on/off switching mechanism. However, several genes and hypothetical CDSs that are unlinked to the pmp genes do indeed carry mutations that are present at frequencies consistent with those of the observed off phenotypes. Investigation of the impact of these mutations on pmp expression is ongoing.

In summary, our studies have established the existence of an efficient expression shutoff mechanism involving the whole pmp gene family of C. trachomatis which may correlate with the observed variation in Pmp-specific antibody profiles of C. trachomatis-infected patients. Like other paralogous gene families of bacterial pathogens with small genomes such as Rickettsia, Mycoplasma, Ehrlichia and the spirochetes (Palmer, 2002), the pmp gene family of C. trachomatis may serve the dual role of maintaining critical, niche-specific pathogenesis-related functions while providing antigenic diversity when infecting chlamydiae face the adaptive immune response of the host.

Experimental Procedures

Chlamydia and cell culture

The C. trachomatis lab reference serovars D/UW-3/CX, E/ UW5-CX and L2/434 were cultivated in Hela 229 cells in 100-mm2 tissue culture dishes at 37°C with 5% CO2 in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM, Mediatech, Herdon, VA) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Atlanta Biologicals, Lawrenceville, GA), Gentamycin (25 µg/ml; Quality Biological, Gaithersburg, MD) and Fungizone (1.25 µg/ml; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Clonality of the serovar E strain was verified by 454 pyrosequencing. Confluent monolayers were pretreated with DEAE-Dextran (30 µg/ml) and inoculum (1ml per dish, yielding a 70–80% infection rate) in SPG (0.25M sucrose, 10mM sodium phosphate and 5mM l-glutamic acid). Infected monolayers were rocked gently for 2 h at 25°C, freshly FBS-supplemented DMEM was added, and the cultures were incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2. For all infections, addition of fresh medium to dishes marked the time of infection [t=0 hour post-infection (hpi)]. EBs were harvested at 48 hpi and purified by step gradient centrifugation using 40%, 44% and 54% Urografin-370 (Schering, AG, Germany) following standard protocols (Schachter and Wyrick, 1994; Caldwell et al., 1981).

RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from C. trachomatis serovar D/UW-3/CX, E/ UW5-CX and L2/434 -infected or mock-infected Hela 229 cell cultures at 42 hpi with TRIzol reagent (Gibco-BRL, Life technologies) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Standardized total RNA was treated with RQ1 RNase-free DNase (Promega, Madison, WI) and divided into reverse transcriptase (RT) and no-RT groups. Primers were designed for each pmp gene and for 16S rRNA gene using the FastPCR software (Table 1). Two-step RT-PCR was performed using SuperScript™ II RT kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) to generate first-strand cDNA followed by PCR according to the manufacturers’ protocols. The PCR products were visualized by electrophoresis in a 1% agarose gel.

Table 1.

Oligonucleotide primers used for RT-PCR

| Gene | Primersa | Primer sequence (5’to3’) | Gene Location | Amplicon size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pmpA | pmpA-3 | CATACGCTTAACTCCCTCCCT | 2238-2258 | 455 |

| pmpA-4 | CAAAAGAGCTATTCCCTAAGCAG | 2692-2670 | ||

| pmpB | pmpB-3 | TCGTCGCTGGGTATACATACC | 4257-4277 | 429 |

| pmpB-4 | AAAGGAAGTGCCCAACCAT | 4685-4667 | ||

| pmpC | pmpC-5 | TTAGTGCTCCCTACAGACTCATCA | 4150-4173 | 501 |

| pmpC-6 | GGATCCTTTGTGAGTGTAGTTATTC | 4650-4626 | ||

| pmpD | pmpD-3 | CAGGAGGGGACAGTAGAAGC | 3304-3323 | 406 |

| pmpD-4 | TCAGAGCAGACAAGACAGCC | 3709-3690 | ||

| pmpE | pmpE-3 | CCCATGCTCTGTCATCACAG | 1712-1731 | 403 |

| pmpE-4 | TCTTGGTAAACCATCATGCC | 2114-2095 | ||

| pmpF | pmpF-3 | ACCTCCATCGCTGAGCAGAA | 2008-2027 | 404 |

| pmpF-4 | CCATGAGCTCCTGATGCTTG | 2411-2392 | ||

| pmpG | pmpG-3 | CGAATCCTCCTACCAATCCTC | 1763-1783 | 366 |

| pmpG-4 | CCAAAGAAGCTACTCGCTCAG | 2128-2108 | ||

| pmpH | pmpH-3 | ACTCTCTTTGGGTAGCGGGA | 2114-2133 | 484 |

| pmpH-4 | AAATTATGCTCGGCACCCAC | 2597-2578 | ||

| pmpI | pmpI-5 | GTGCCTCATCCAGAACGTCA | 1702-1721 | 363 |

| pmpI-6 | TAGAGGGGTAGCGAGTTGCG | 2064-2045 | ||

| 16SrRNA | 16SrRNA-1 | CTCGCAAGGGTGAAACTCA | 901-919 | 422 |

| 16SrRNA-2 | TGCAGACTACAATCCGAACTG | 1322-1302 |

Primers designed based on published sequence of reference strain D/UW-3/Cx (GenBank Accession No. for 16SrRNA is 884531)

Generation and characterization of Pmp-specific mAbs and guinea pig (GP) or rabbit pAbs

The recombinant N-terminal fragments containing the predicted passenger domain of the Pmp proteins (rPmp-N) were constructed as previously described (Tan et al., 2009). Briefly, PCR products from C. trachomatis serovar E genomic DNA encoding individual Pmps were cloned into the pET30 vector and expressed in E. coli BL21 strain upon induction. Inclusion bodies enriched with rPmps were partially purified by ultrasonication and differential extraction with Triton X-100. Prior to immunization, all rPmp immunogens were either denatured in 1% SDS followed by extensive dialysis against PBS buffer to promote refolding or extracted from preparative SDS-PAGE gels. PmpD and PmpI-specific mouse mAbs were generated as previously described (Kohler and Milstein, 1975) with modifications. Briefly, mice were immunized with purified C. trachomatis serovar E EB lysates (50µg/immunization/animal) mixed with Freund’s Complete Adjuvant (FCA) and boosted twice with 50µg SDS-PAGE gel extracted rPmpD-N or rPmpI-N in Freund’s Incomplete Adjuvant (FIA). Mouse tail bleeds were tested against rPmps by immunoblot before the fusion of spleen cells from immunized mice with the NS1 myeloma cells. The hybridoma culture supernatants were then screened for antibodies to rPmpD and rPmpI by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and immunoblot analysis. Supernatants of selected hybridoma cell cultures were collected and used as the source of anti-PmpD/I mAbs. Polyclonal antibodies specific for PmpA, B, C, E, F, G and H were generated upon immunization of guinea pigs with rPmp-N (rPmpA-N, B-N, C-N, E-N, F-N, G-N, and H-N) and of rabbit with rPmpB-N. For each animal, approximately 500µg of immunogen mixed with the same volume of FCA was used for primary immunization and two subsequent boosters containing rPmps with FIA were administered. Antibody reactivity was checked before the antisera were collected.

PmpD and PmpI-specific mAbs, rabbit anti-PmpB antiserum and guinea pig PmpA, B, C, E, F, G and H-specific antisera were characterized against the 13 rPmps [including both full length (FL) and N-terminal fragments: rPmpA-FL, A-N, B-N, C-N, D-FL, D-N, E-FL, E-N, F-FL, F-N, G-N, H- FL and I-FL] partially purified from E. coli BL21 by ultrasonication and differential Triton X-100 extraction and purified serovar E EB lysates by immunoblot of independent SDS-PAGE gels using AP-conjugated anti-mouse, anti-rabbit or anti-GP secondary antibody (KPL, MD, USA). Before use, all pAbs were adsorbed with inclusion bodies of E. coli expressing an irrelevant antigen (recombinant β-galactosidase prepared by a method similar to that used for rPmps) to remove any non-specific reactivity.

Indirect immunofluorescence (IF) microscopy

Hela 229 cells grown on glass coverslips in 48-well plates were infected with serovar E/ UW5-CX at a MOI of 0.5. At the indicated hpi, cells were washed with PBS, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100, 0.05% SDS and blocked for 30 min with 0.2% BSA in PBS. Monolayers were double-stained using 2 different combinations of primary antibodies: a Pmp-specific antibody and a mAb specific for chlamydial EF-Tu, or two primary antibodies specific for two individual Pmps generated in 2 different animals. Rabbit anti-PmpB and GP anti-PmpA/B/C/E/F/G/H antisera were pre-adsorbed with insoluble His-tagged recombinant beta-galactosidase to remove any non-specific reactivity prior to staining. Various animal-specific Alexa fluor-conjugated secondary antibodies (Molecular Probes/Invitrogen) were used to differentiate between the target antigens. Alexa Fluor 594 dye (Molecular Probes/Invitrogen) was conjugated to anti-EF-Tu mAb for double staining with anti-PmpD/I mAbs. Inclusions were observed on a Zeiss fluorescence microscope under 400 × magnification. The relative “Pmp-off” frequencies were estimated by enumerating the number of Pmp-negative inclusions in 10 fields of confluent infected cells under 200 × magnification in at least three independent experiments.

For testing chlamydial surface localization, cells were blocked with 0.2% BSA after fixation without permeabilization using Triton-X-100 and 0.05% SDS. Monolayers were stained with Pmp/MOMP/EF-Tu-specific antibodies and counterstained with Alexa 546 conjugated Phalloidin. Images are examined at 200×/400× magnification on an Axio Imager Z.1 microscope (Carl Zeiss, Germany).

Electron microscopy

C. trachomatis serovar E-infected Hela cell cultures were harvested at 42 hpi and were extracted by 30% Urografin-370 centrifugation. Chlamydiae paticles were adsorbed onto formva-coated grids for 1 min and blocked with 0.1 M phosphate buffer containing 1% BSA. Grids were then incubated with rabbit anti-MOMP or GP anti-PmpB antiserum for 30 min, washed with three changes of phosphate buffer containing 1% BSA and incubated with 10 nm gold-conjugated animal-specific secondary antibodies. Immunolabelled grids were then negatively stained with 1% phosphotungstic acid (PTA), air dried and observed in a transmission electron microscope (TEM; Tecnai T12, FEI) at 80 kV.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH RO1 AI51417 to RcH and PMB. CT was supported by a special fellowship from the UMB Graduate Program for a portion of this work. The authors also thank Dr. Kelley Hovis for her critical reading of the manuscript.

References

- Barbour AG, Tessier SL, Stoenner HG. Variable major proteins of Borrellia hermsii. J Exp Med. 1982;156:1312–1324. doi: 10.1084/jem.156.5.1312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birkelund S, Knudsen K, Madsen AS, Falk E, Mygind P, Christiansen G. Differential expression of Omp4 and Omp5 after infection of C57-black mice? In: Stephens RS, ale, editors. Ninth International Symposium on Human Chlamydial Infection. Napa, CA: International Chlamydia Symposium; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard TJ, Mabey DC. Chlamydial infections. Br J Clin Pract. 1994;48:201–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell HD, Kromhout J, Schachter J. Purification and partial characterization of the major outer membrane protein of Chlamydia trachomatis. Infection & Immunity. 1981;31:1161–1176. doi: 10.1128/iai.31.3.1161-1176.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crane DD, Carlson JH, Fischer ER, Bavoil P, Hsia RC, Tan C, et al. Chlamydia trachomatis polymorphic membrane protein D is a species-common pan-neutralizing antigen. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:1894–1899. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508983103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donelson JE. Antigenic variation and the African trypanosome genome. Acta Trop. 2003;85:391–404. doi: 10.1016/s0001-706x(02)00237-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes JP, Bruno WJ, Borrego MJ, Dean D. Recombination in the genome of Chlamydia trachomatis involving the polymorphic membrane protein C gene relative to ompA and evidence for horizontal gene transfer. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:4295–4306. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.13.4295-4306.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes JP, Nunes A, Bruno WJ, Borrego MJ, Florindo C, Dean D. Polymorphisms in the nine polymorphic membrane proteins of Chlamydia trachomatis across all serovars: evidence for serovar Da recombination and correlation with tissue tropism. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:275–286. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.1.275-286.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimwood J, Stephens RS. Computational analysis of the polymorphic membrane protein superfamily of Chlamydia trachomatis and Chlamydia pneumoniae. Microb Comp Genomics. 1999;4:187–201. doi: 10.1089/omi.1.1999.4.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimwood J, Olinger L, Stephens RS. Expression of Chlamydia pneumoniae polymorphic membrane protein family genes. Infect Immun. 2001;69:2383–2389. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.4.2383-2389.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagblom P, Segal E, Billyard E, So M. Intragenic recombination leads to pilus antigenic variation in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Nature. 1985;315:156–158. doi: 10.1038/315156a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson IR, Lam AC. Polymorphic proteins of Chlamydia spp.--autotransporters beyond the Proteobacteria. Trends Microbiol. 2001;9:573–578. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(01)02234-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell-Adams B, Seifert HS. Molecular models accounting for the gene conversion reactions mediating gonococcal pilin antigenic variation. Mol Microbiol. 2000;37:1146–1158. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.02067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalman S, Mitchell W, Marathe R, Lammel C, Fan J, Hyman RW, et al. Comparative genomes of Chlamydia pneumoniae and C. trachomatis. Nature Genetics. 1999;21:385–389. doi: 10.1038/7716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karunakaran KP, Rey-Ladino J, Stoynov N, Berg K, Shen C, Jiang X, et al. Immunoproteomic discovery of novel T cell antigens from the obligate intracellular pathogen Chlamydia. J Immunol. 2008;180:2459–2465. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.4.2459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiselev AO, Stamm WE, Yates JR, Lampe MF. Expression, processing, and localization of PmpD of Chlamydia trachomatis serovar L2 during the chlamydial developmental cycle. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e568. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohler G, Milstein C. Continuous cultures of fused cells secreting antibody of predefined specificity. Nature. 1975;256:495–497. doi: 10.1038/256495a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindquist EA, Stephens RS. Transcriptional Activity of a Sequence Variable Protein Family in Chlamydia trachomatis. In: Stephens RS, Byrne GI, Christiansen G, Clarke IN, Grayston JT, Rank RG, et al., editors. Ninth International Symposium on Human Chlamydial Infection. Napa, California, USA: International Chlamydia Symposium; 1998. pp. 259–262. [Google Scholar]

- Longbottom D, Findlay J, Vretou E, Dunbar SM. Immunoelectron microscopic localisation of the OMP90 family on the outer membrane surface of Chlamydia psittaci. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1998;164:111–117. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1998.tb13075.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moulder JW. Interaction of chlamydiae and host cells in vitro. Microbiological Reviews. 1991;55:143–190. doi: 10.1128/mr.55.1.143-190.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mygind PH, Christiansen G, Roepstorff P, Birkelund S. Membrane proteins PmpG and PmpH are major constituents of Chlamydia trachomatis L2 outer membrane complex. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2000;186:163–169. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2000.tb09098.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niessner A, Kaun C, Zorn G, Speidl W, Turel Z, Christiansen G, et al. Polymorphic membrane protein (PMP) 20 and PMP 21 of Chlamydia pneumoniae induce proinflammatory mediators in human endothelial cells in vitro by activation of the nuclear factor-kappaB pathway. J Infect Dis. 2003;188:108–113. doi: 10.1086/375827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunes A, Gomes JP, Mead S, Florindo C, Correia H, Borrego MJ, Dean D. Comparative expression profiling of the Chlamydia trachomatis pmp gene family for clinical and reference strains. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e878. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer GH. The highest priority: what microbial genomes are telling us about immunity. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2002;85:1–8. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2427(01)00415-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen AS, Christiansen G, Birkelund S. Differential expression of Pmp10 in cell culture infected with Chlamydia pneumoniae CWL029. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2001;203:153–159. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2001.tb10834.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read TD, Myers GS, Brunham RC, Nelson WC, Paulsen IT, Heidelberg J, et al. Genome sequence of Chlamydophila caviae (Chlamydia psittaci GPIC): examining the role of niche-specific genes in the evolution of the Chlamydiaceae. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:2134–2147. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read TD, Brunham RC, Shen C, Gill SR, Heidelberg JF, White O, et al. Genome sequences of Chlamydia trachomatis MoPn and Chlamydia pneumoniae AR39. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:1397–1406. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.6.1397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocha EP, Pradillon O, Bui H, Sayada C, Denamur E. A new family of highly variable proteins in the Chlamydophila pneumoniae genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:4351–4360. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkf571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schachter J, Wyrick PB. Culture and isolation of Chlamydia trachomatis. In: Clark VL, Bavoil PM, editors. Methods in Enzymology. Volume 236. Bacterial Pathogenesis, part B. Interaction of pathogenic Bacteria with Host Cells. San Diego: Academic Press, Inc.; 1994. pp. 377–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw AC, Gevaert K, Demol H, Hoorelbeke B, Vandekerckhove J, Larsen MR, et al. Comparative proteome analysis of Chlamydia trachomatis serovar A, D and L2. Proteomics. 2002;2:164–186. doi: 10.1002/1615-9861(200202)2:2<164::aid-prot164>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirai M, Hirakawa H, Ouchi K, Tabuchi M, Kishi F, Kimoto M, et al. Comparison of Outer Membrane Protein Genes omp and pmp in the Whole Genome Sequences of Chlamydia pneumoniae Isolates from Japan and the United States. J Infect Dis. 2000;181:S524–S527. doi: 10.1086/315616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skipp P, Robinson J, O'Connor CD, Clarke IN. Shotgun proteomic analysis of Chlamydia trachomatis. Proteomics. 2005;5:1558–1573. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200401044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens RS, Kalman S, Lammel C, Fan J, Marathe R, Aravind L, et al. Genome sequence of an obligate intracellular pathogen of humans: Chlamydia trachomatis. Science. 1998;282:754–759. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5389.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern A, Meyer TF. Common mechanism controlling phase and antigenic variation in pathogenic neisseriae. Mol Microbiol. 1987;1:5–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1987.tb00520.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson KA, Taylor LD, Frank SD, Sturdevant GL, Fischer ER, Carlson JH, et al. Chlamydia trachomatis Polymorphic Membrane Protein D Is an Oligomeric Autotransporter with a Higher-Order Structure. Infect Immun. 2009;77:508–516. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01173-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan C, Hsia R-c, Shou H-z, Haggerty CL, Ness RB, Gaydos CA, et al. Chlamydia trachomatis-infected patients display variable antibody profiles against the nine-member polymorphic membrane protein family. Infect. Immun. 2009;77:3218–3226. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01566-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanzer RJ, Longbottom D, Hatch TP. Identification of polymorphic outer membrane proteins of Chlamydia psittaci 6BC. Infect Immun. 2001;69:2428–2434. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.4.2428-2434.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson NR, Yeats C, Bell K, Holden MT, Bentley SD, Livingstone M, et al. The Chlamydophila abortus genome sequence reveals an array of variable proteins that contribute to interspecies variation. Genome Res. 2005;15:629–640. doi: 10.1101/gr.3684805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandahl BB, Birkelund S, Demol H, Hoorelbeke B, Christiansen G, Vandekerckhove J, Gevaert K. Proteome analysis of the Chlamydia pneumoniae elementary body. Electrophoresis. 2001;22:1204–1223. doi: 10.1002/1522-2683()22:6<1204::AID-ELPS1204>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandahl BB, Pedersen AS, Gevaert K, Holm A, Vandekerckhove J, Christiansen G, Birkelund S. The expression, processing and localization of polymorphic membrane proteins in Chlamydia pneumoniae strain CWL029. BMC Microbiol. 2002;2:36. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-2-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wehrl W, Brinkmann V, Jungblut PR, Meyer TF, Szczepek AJ. From the inside out--processing of the Chlamydial autotransporter PmpD and its role in bacterial adhesion and activation of human host cells. Mol Microbiol. 2004;51:319–334. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03838.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]