Abstract

Catalytic Pd(OAc)2 and polymethylhydrosiloxane (PMHS), in conjunction with aqueous KF, and a catalytic amount of an aromatic chloride, effects the chemo, regio, and stereoselective deoxygenation of benzylic oxygenated substrates at room temperature in THF. Preliminary mechanistic experiments suggest the process to involve palladium-nanoparticle catalyzed hydrosilylation followed by C–O reduction. The chloroarene additive appears to facilitate the hydrogenolysis process through the slow controlled release of HCl.

In the early 1990’s, Tour1 and Crabtree2 independently reported on how dispersing palladium throughout a siloxane polymer matrix raises the catalytic activity of the metal. Originally termed Pd-colloids, in 2004 Chauhan3 unequivocally showed that by mixing Pd(OAc)2 with polymethylhydrosiloxane (PMHS) formed polysiloxane-encapsulated Pd-nanoclusters.

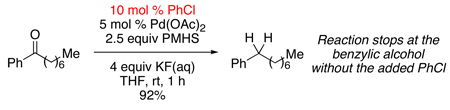

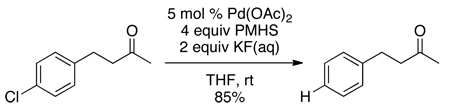

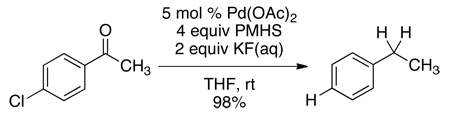

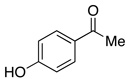

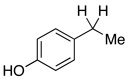

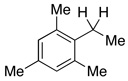

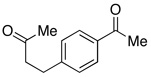

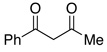

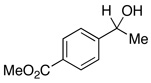

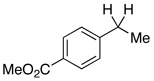

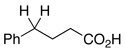

We had previously reported that Pd(OAc)2/PMHS in the presence of aqueous KF rapidly hydrodehalogenated chloroarenes.4 Despite PMHS’ ability to reduce ketones to alcohols,5 this system chemoselectively dechlorinated 4-(4-chlorophenyl)-2-butanone (eq 1). In contrast, when 4’-chloroacetophenone was placed under the same conditions, it was fully reduced to ethylbenzene (eq 2).

|

(1) |

|

(2) |

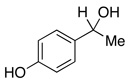

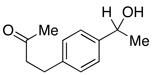

Since transfer hydrogenolysis of activated C–O bonds by PMHS are known,6 we were not entirely surprised by this result, until we examined the reactivity of acetophenone. After being exposed to the Pd(OAc)2/PMHS/KF(aq) conditions for 24 hours, the acetophenone afforded no visible amounts of ethyl benzene, stopping instead at 1-phenylethanol (Table 1, entry 1).

Table 1.

Screening Halides as Deoxgyenation Additives

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | halide source | time (h) | %yielda PhEt |

%yielda alcohol |

| 1 | none | 24 | 0 | 98 |

| 2 | PhCl | 1 | 100 | 0 |

| 3 | PhBr | 2 | 22 | 78 |

| 4 | PhI | 16 | 0 | 25 |

| 5 | Bu4NCl | 3.5 | traceb | 30 |

| 6 | CsCl | 24 | traceb | 98 |

| 7 | LiCl | 24 | traceb | 100 |

| 8 | PhONf | 1 | traceb | 99 |

| 9 | PhONf + LiCl | 1 | 97 | 0 |

| 10 | HCl | 1 | 15 | 40 |

| 11 | 1-chlorobutane | 1 | traceb | 22 |

| 12 | TMS-Cl | 1 | 95 | 0 |

Average of two runs as determined by 1H-NMR with CH2Cl2 as an internal standard.

Determined by GC

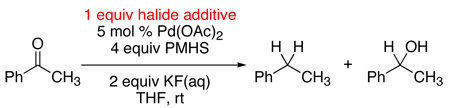

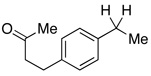

Empirically, the presence of a chloro group was influencing the reactivity of the benzylic ketone/alcohol. Yet, GC monitoring of the 4’-chloroacetophenone reduction indicated the intermediacy of acetophenone. Thus the chloro group of 4-chloroacetophenone was not directly enhancing its reactivity. An investigation was undertaken to uncover why in situ generated acetophenone undergoes full deoxygenation, while subjecting acetophenone starting material to the “same” reduction conditions stopped at the alcohol. Through experimentation, we found that by simply starting the reaction in the company of chlorobenzene, acetophenone was quantitatively reduced to ethylbenzene after 1 hour at room temperature. Moreover, 10 mol % chlorobenzene7 proved equally effective at facilitating the reaction.

To the best of our knowledge this is the first example of chlorobenzene serving as a productive additive in Pd-mediated reductions.8,9,10 To explore this curious finding further, we surveyed a variety of chlorides and related additives against the reaction of acetophenone with Pd(OAc)2/PMHS/KF(aq).

Where chlorobenzene efficiently facilitated deoxygenation, among bromobenzene, iodobenzene, and phenyl nonaflate (entries 2–4, 8) only PhBr showed any effectiveness as an additive with its reaction affording ethylbenzene in 22% yield. With PhI and PhONf, the reductions stopped at 1-phenylethanol. It was also noted that relative to chlorobenzene, PhBr, PhI, and PhONf were themselves reduced very rapidly to benzene. A number of chloride salts were also tested (entries 5–7), but only trace amounts of ethylbenzene were formed in their presence. Interestingly though, while LiCl (entry 7) and PhONf (entry 8) were ineffective additives on their own, when both were added to the reaction (entry 9) acetophenone was quantitatively converted to ethylbenzene.

These data pointed to the possible participation of an Ar–Pd–Cl species.11 Such an intermediate could play many roles. Among the possibilities, the aromatic chloride might serve as a ligand on the active Pd-catalyst or in some other way (e.g. transmetallation) positively alter the reactivity of the polysiloxane-matrix. It could also be that Ar–Pd(II)–Cl in the presence of PMHS and water simply serves as a source of HCl.12 Indeed, adding 1 equiv HCl to the acetophenone reaction (entry 10) gave 15% PhEt.

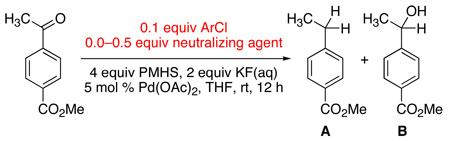

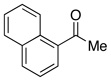

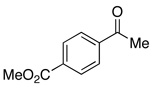

Though certainly speculation, we were of the opinion that these preliminary results best fit a scenario where chlorobenzene provided for a controlled release of HCl. Supposing this to be the case, entries 2 vs. 10 would indicate that the rate at which HCl enters the reaction affects the efficiency of the overall reaction. As such, we deemed it useful to examine other additives that could generate HCl in situ. However, 1-chlorobutane (entry 11), which could afford HCl via β-hydride elimination, was not an effective additive. On the other hand, adding TMSCl to the reaction was beneficial, with deoxygenation of the ketone occurring in 94% (entry 12). We also screened various chloroarenes under the assumption that they would form Ar–Pd(II)–Cl species and in turn release HCl at different rates. Anticipating subtle differences between chloroarenes, we chose the relatively slow reacting methyl 4-acetylbenzoate as the starting ketone (Table 2). In the presence of 10 mol % PhCl, this substrate afforded 21% of methyl 4-ethylbenzoate (A) and 77% of methyl 4-(1-hydroxyethyl)benzoate (B). A set of sterically and electronically varied chloroarenes was then assessed. As seen in Table 2, the ratio of A/B was highest with 4-chloroanisole (entry 3). To further test the hypothesis that chloroarene derived HCl was the deoxygenation promoter, the reduction of methyl 4-acetylbenzoate was performed in the presence of both 4-chloroanisole and various acid scavengers. In all instances (entries 8–11) the deoxygenations were suppressed, albeit to unequal extents.

Table 2.

Screening Halides as Deoxgyenation Additives

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| entry | ArCl | neutralizing agent |

%yielda (A/B/sm) |

| 1 | chlorobenzene | – | 21 / 77 / – |

| 2 | 2-chloro-m-xylene | – | 13 / 74 / – |

| 3 | 4-chloroanisole | – | 39 / 46/ – |

| 4 | 4-chlorobenzo-trifluoride | – | 32 / 28 / 10 |

| 5 | 2-chloropyridine | – | – / 13 / 85 |

| 6 | o-dichlorobenzene | – | 38 / 61 / – |

| 7 | hexachlorobenzene | – | 30 / 66 / 2 |

| 8 | 4-chloroanisole | 2,6-lutidineb | – / 94 / 1 |

| 9 | 4-chloroanisole | DTBMPc,d | 28 / 65 / – |

| 10 | 4-chloroanisole | proton-sponged | – / 98 / – |

| 11 | 4-chloroanisole | propylene oxided | 37 / 57 / – |

Average isolated yield over two runs.

0.1 equiv.

2,6-di-tert-butyl-4-methylpyridine.

0.5 equiv.

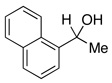

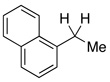

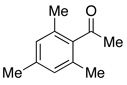

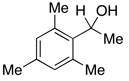

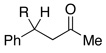

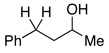

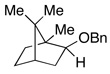

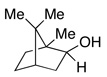

In addition to these reactions being mechanistically curious, chlorobenzene represents a unique and attractive additive. Even relative to TMSCl, chlorobenzene is cheap, stable, and otherwise inert. For these reasons we presented these conditions to a variety of substrates bearing benzylic C–O bonds (Table 3). Substrate screening was carried out with 10 mol % PhCl, 5 mol % Pd(OAc)2, 1.5–4.0 equiv PMHS, 4 equiv KF, in (5:2) THF/H2O at room temperature for 1 h.13,14 We found that increasing the steric environment about the carbonyl hindered the deoxygenation (entries 6, 10, 12–14), with substitution at both ortho positions completely shutting down second reduction (entries 15–16). To evaluate the chemoselectivity of the system 4-(4-acetylphenyl)-butan-2-one (entries 18–21) was prepared and subjected to the reaction conditions, resulting in reduction of only the benzylic ketone. Likewise subjecting 1-phenylbutane-1,3-dione to the reaction conditions (entries 22–24) resulted in deoxygenation of the benzylic carbonyl, along with some reduction of the 3-carbonyl to the alcohol. Similar chemoselectivity was also seen with methyl 4-acethylbenzoate (entry 25).

Table 3.

Deoxygenation Substrate Screeninga

| entry | starting material | equiv PMHS |

Ar-Cl added | product(s) %yieldb | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2.5 | Ph–Cl | 0% | 92% | |||

| 2 | 1.5 | none | 88% | 0% | |||

| 3 |  |

2.5 | Ph–Cl |  |

0% |  |

95% |

| 4 |  |

2.5 | Ph–Cl |  |

0% |  |

86% |

| 5c | 1.5 | none | 67% | 0% | |||

| 6 |  |

2.5 | Ph–Cl |  |

21% |  |

72% |

| 7 | 4.0 | Ph–Cl | 12% | 83% | |||

| 8 | 4.0 | 4-chloroanisole | 0% | 94% | |||

| 9c | 1.5 | none | 99% | 0% | |||

| 10 |  |

2.5 | Ph–Cl |  |

20% |  |

80% |

| 11 | 2.5 | 4-chloroanisole | 0% | 99% | |||

| 12 |  |

4.0 | Ph–Cl |  |

97% | 0% | |

| 13 | 4.0 | 4-chloroanisole | 96% | 0% | |||

| 14c | 1.5 | none | 99% | 0% | |||

| 15 |  |

4.0 | Ph–Cl |  |

0% |  |

0% |

| 16c | 4.0 | none | 0% | 0% | |||

| 17d |  |

2.5 | Ph–Cl |  |

98% |  |

0% |

| 18 |  |

2.5 | Ph–Cl |  |

44% |  |

52% |

| 19 | 4.0 | Ph–Cl | 41% | 57% | |||

| 20 | 4.0 | 4-chloroanisole | 25% | 72% | |||

| 21c | 3.0 | none | 94% | 0% | |||

| 22 |  |

2.5 | Ph–Cl |  |

48% (R = OH)e |  |

11% |

| 23 | 4.0 | Ph–Cl | 33% (R = H) | 46% | |||

| 24c | 1.5 | none | 42% (R = OH) | 0% | |||

| 25 |  |

4.0 | Ph–Cl |  |

73% |  |

25% |

| 26 | 4.0 | 4-chloroanisole | 46% | 52% | |||

| 27d |  |

2.5 | Ph–Cl | 0% | 94%f | ||

| 28c,d | 1.5 | none | 98%f | 0% | |||

| 29g |  |

2.5 | Ph–Cl |  |

67% | ||

| 30c | 1.5 | Ph–Cl |  |

90% | |||

| 31 |  |

2.5 | Ph–Cl |  |

97% (95 %de) | ||

| 32c | 1.5 | none | 99% (79 %de) | ||||

| 33h | 2.5 | Ph–Cl | 62% (81 %ee) |

Conditions: 1 equiv substrate (1 mmol), 5 mol % Pd(OAc)2, 10 mol % PhCl, 2.5 equiv PMHS, 4 equiv KF, 5 mL THF, 2 mL H2O, rt, 1 h.

Average isolated yield of two runs.

Reaction run with 2 equiv KF.

Determined by 1H-NMR with CH2Cl2 as an internal standard.

Plus 7% (R = H).

Toluene was also observed in >95% yield.

31% recovered starting material.

38% recovered starting material.

Entries 27–32 show that the chlorobenzene effect can be seen during the hydrogenolysis of a variety of C–O bonds.15 In the presence of PhCl, benzyl bornyl ether (entry 29) underwent deprotection in 67% yield in less than one hour. In the absence of PhCl only 15% of isobornyl alcohol was formed in one hour and over 8 hours were needed for the reaction to give a comparable yield. Not surprisingly, the rate acceleration that occurs courtesy of PhCl could impact the reactions negatively. For example, the benzyl ether of 1-phenylethanol (entry 7) undergoes hydrogenolysis of both C–O bonds when PhCl is present, whereas without PhCl the reaction was regioselective for hydride delivery to the least substituted benzyl, affording toluene and sec-phenethyl alcohol in near quantitative yields. It should also be noted that the presence of a basic nitrogen inhibited the deoxygenation (entry 17), affording only the alcohol, presumably due to HCl sequestration.

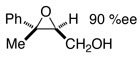

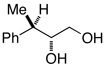

To evaluate the regio- and stereoselectivity of the reduction, a stereodefined benzylic epoxide (entry 31) was subjected to the conditions. Here the 1,2-diol was generated in high yield and 95% de.16 Reaction of the epoxide without PhCl also afforded the 1,2-diol quantitatively, but with decreased de (entry 32). A stereodefined17 tertiary benzylic alcohol (entry 33), afforded (S)-3-phenyl-1-butanol with no loss of enantiomeric excess and retention of configuration.18 Finally, as evidenced by entries 8 vs 7, 11 vs 10, 20 vs 19, and 26 vs 25, changing the aryl chloride additive from chlorobenzene to 4-chloroanisole enabled the deoxygenation of some of the more difficult substrates.

More work is needed to secure a mechanism for this process, as well as to determine how the additives impact the nature of the Pd-nanoparticles. That said, the observed memory of chirality (Table 3, entry 33) and cyclobutane stability (Table 3, entries 6–9) argue against the presence of benzyl radicals. Based on these and other data, we favor a mechanism were the ketone is first reduced to the alcohol by Pd-catalyzed hydrosilylation. In the interim a reduction of chlorobenzene affords benzene and a chlorosiloxane. The chlorosiloxane is then hydrolyzed by water present in the reaction to form HCl and the silanol. The HCl then facilitates12,19 Pd-catalyzed transfer hydrogenolysis of the benzylic C–O bond, where the hydrogen is in part formed from the PMHS and water.6 This last step is supported by reactions run in D2O, which saw ~37% deuterium incorporation at the newly formed benzylic methylene.20

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank the NSF, NIH, and the Astellas USA Foundation for generous support.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Experimental details and product characterization data. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.(a) Tour JM, Cooper JP, Pendalwar SL. J. Org. Chem. 1990;55:3452–3453. [Google Scholar]; (b) Tour JM, Pendalwar SL, Cooper JP. Chem. Mater. 1990;2:647–649. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fowley LA, Michos D, Luo X-L, Crabtree RH. Tetrahedron Lett. 1993;34:3075–3078. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chauhan BPS, Rathore JS, Bandoo T. J. Amer. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:8493–8500. doi: 10.1021/ja049604j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rahaim RJ, Jr, Maleczka RE., Jr Tetrahedron Lett. 2002;43:8823–8826. [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Larson GL, Fry JL. Org. React. 2008;71:1–771. [Google Scholar]; (b) Mimoun H. J. Org. Chem. 1999;64:2582–2589. doi: 10.1021/jo994010y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Lawrence NJ, Drew MD, Bushell SM. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1. 1999:3381–3391. [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Blum J, Bitan G, Marx S, Vollhardt KPC. J. Mol. Catal. 1991;66:313–319. [Google Scholar]; (b) Blum J, Pri-Bar I, Alper H. J. Mol. Catal. 1986;37:359–367. [Google Scholar]

- 7.As little as 1 mol% chlorobenzene facilitated deoxygenation, but reactions stopped at the alcohol with <1 mol% PhCl.

- 8.For the productive use of stoichiometric PhCl in Pd-mediated oxidations see Bei X, Hagemeyer A, Volpe A, Saxton R, Turner H, Guram AS. J. Org. Chem. 2004;69:8626–8633. doi: 10.1021/jo048715y. Guram AS, Bei X, Turner HW. Org. Lett. 2003;5:2485–2487. doi: 10.1021/ol0347287.

- 9.For related observations see Maleczka RE, Jr, Rahaim RJ, Jr, Teixeira RR. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002;43:7087–7090. Zigterman JL, Woo JCS, Walker SD, Tedrow JS, Borths CJ, Bunel EE, Faul MM. J. Org. Chem. 2007;72:8870–8876. doi: 10.1021/jo701682c.

- 10.For other surprising aryl halide and halide effects, in transition metal catalysis see Chrovian CC, Montgomery J. Org. Lett. 2007;9:537–540. doi: 10.1021/ol063028+. Fagnou K, Lautens M. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2002;41:26–47. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020104)41:1<26::aid-anie26>3.0.co;2-9.

- 11.Note: Using PdCl2 in place of Pd(OAc)2, with no additives only yielded 8% of ethylbenzene along with 71% benzyl alcohol.

- 12.Rylander P. Catalytic Hydrogenation in Organic Synthesis. New York: Academic; 1979. p. 274. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Typical procedure: Into a 25 mL round bottom flask, that had been purged with nitrogen, was charged Pd(OAc)2 (0.05 mmol, 11 mg), freshly distilled THF (5 mL), and then the ketone (1.0 mmol). The flask was fitted with a balloon of nitrogen. A solution of potassium fluoride (4 mmol, 232 mg) in degassed water (2 mL) was added via syringe into the reaction, followed by chlorobenzene (0.1 mmol, 0.01 mL). PMHS (2.5 mmol, 0.15 mL) was then dropwise added via syringe into the reaction mixture. The resulting reaction was stirred for one hour. Ether was added to the reaction mixture, the layers were separated, and the aqueous layer was back extracted with ether. The combined organics were concentrated and subjected to flash chromatography. (Caution: Rapid addition of PMHS can result in vigorous gas evolution! For reactions run on large scale, it is recommended that the reaction flask be fitted with a reflux condenser.)

- 14.As little as 1 mol % Pd(OAc)2 can be used provided the amounts of PMHS and KF are raised to 5 and 10 equivalents, respectively. However, increasing the amount of PMHS can make purifications more difficult as PMHS can undergo sol-gel processes.

- 15.For other Pd-mediated reductions of benzylic C–O bonds see Felpin F-X, Fouquet E. Chem. Eur. J. 2010;16:12440–12445. doi: 10.1002/chem.201001377. Mirza-Aghayan M, Boukherroub R, Rahimifard M. Tetrahedron Lett. 2009;50:5930–5932. Thiery E, Le Bras J, Muzart J. Green Chem. 2007;9:326–327. Coleman RS, Shah JA. Synthesis. 1999:1399–1400. Keinan E, Greenspoon N. J. Org. Chem. 1983;48:3545–3548. Lipowitz J, Bowman SA. J. Org. Chem. 1973;38:162–165.

- 16.3-Phenyl-1-butanol (3%) was also isolated.

- 17.The %ee and absolute configuration of the starting material were determined by derivation to Mosher’s ester with (S)-(+)-MTPA-Cl. See Dale JA, Mosher HS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1973;95:512–519.

- 18.The %ee and absolute configuration of the product were determined by derivation with (R)-MPA. See Trost BM, Curran DP. Tetrahedron Lett. 1981;22:4929–4932.

- 19.Consistent with this proposal is the quantitative deoxygenation of sec-phenethyl alcohol and its TBS ether in the presence of catalytic HCl.

- 20.A description of the deuterium labeling and silicon hydride screening experiments can be found in the Supporting Information.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.