Abstract

Differential mRNA stability is an important mechanism for regulation of virulence factors in Streptococcus pyogenes (group A streptococcus, GAS), a serious and prevalent human pathogen. We have described 2 Classes of mRNA in GAS that are distinguishable by (1) stability in the stationary phase of growth, (2) kinetics of decay in exponential phase and (3) effect of depletion of RNases J1 and J2 and polynucleotide phosphorylase (PNPase) on decay in exponential phase. We discuss features of the structure of an mRNA that appear to be important for determining the Class to which it belongs and present a model to explain differential mRNA decay.

Key words: Streptococcus pyogenes, mRNA stability, mRNA decay, RNase J1, RNase J2, PNPase, growth phase control

Introduction

Streptococcus pyogenes (group A streptococcus, GAS) is a very prevalent Gram+ bacterium that infects humans exclusively. It produces a wide variety of diseases, ranging from mild skin and throat infections (impetigo and pharyngitis) to systemic and life threatening infections (streptococcal toxic shock syndrome and necrotizing fasciitis).1–3 A conservative estimate of 500,000 deaths per year globally due to GAS infections has been calculated, making this bacterium one of the top 10 infectious causes of mortality.3 If left untreated, GAS throat and skin infections can lead to complications involving the heart and kidneys (rheumatic heart disease and glomerulonephritis, respectively), so prompt antibiotic treatment is imperative.4 However, although all GAS strains are still sensitive to penicillin, there are reports of up to 35% treatment failure with this antibiotic.5 In addition, some GAS strains are resistant to second line antibiotics used for patients allergic to penicillin.6 Therefore, a better understanding of the pathophysiology of this prevalent human pathogen is essential so that more effective regimens of treatment and disease prevention can be developed.

Like most pathogens, GAS produces many virulence factors. Regulation of their expression in response to environmental conditions results in the success of this bacterium and determines the type of disease manifestation it produces.7 Regulation of virulence gene expression in GAS has been studied extensively at the level of transcription and, in all cases, “growth phase regulation” overrides all other types of control. Even when all repressors are absent and all activators are present, genes are expressed only in the appropriate phase of growth.8 Recently, we found that mRNA decay plays a major role in growth phase regulation.9

Definition of Two Classes of mRNAs in GAS and Model for their Differential Decay

We found that most messages (including that for the has operon, which encodes the enzymes for synthesis of the hyaluronic acid capsule) are difficult to detect at two hours into stationary phase.9 We called these Class I messages. However, transcripts of a few genes are present in greater quantity in stationary than in exponential phase. These genes encode known or suggested virulence factors for GAS (sagA, encoding streptolysin S, sda encoding a DNAse and arc, encoding arginine deiminase, which plays a role in pH homeostasis). We found that all of these messages, which we designated Class II, have extremely long half-lives (≥100 min) at two hours into stationary phase, as determined by RNase protection and northern blot analyses.9 To distinguish the effect of transcription initiation from that of mRNA decay on the amount of a Class I transcript in stationary phase, we expressed has (Class I) from the promoter Psag, which normally produces a Class II message. The has message expressed from Psag decayed rapidly in stationary phase (half life 7 min), indicating that decay rate is a major determinant of growth phase regulation and that decay rate underlies the distinction between the two mRNA Classes.9

Their difference in stationary phase stability suggests that Class I and Class II transcripts decay by different pathways. In agreement with this, their decay kinetics in exponential phase differ. We found that two representative messages of Class I (has and gyr, encoding gyrase) decay with monophasic kinetics, while two representative messages of Class II (sag and sda) show a 10–20 min delay after transcription is stopped before decay begins.10

To identify ribonucleases that differentially affect decay of these two mRNA Classes, we individually deleted putative genes for 3′-to-5′ exoribonucleases from the chromosome of GAS. We learned that rnr (which codes for RNase R, a processive 3′-to-5′ exoribonuclease that cleaves structured mRNA)11,12 and yhaM (encoding YhaM, a 3′-to-5′ exoribonuclease present only in Gram+ bacteria)13 have little effect on decay of Class II mRNAs, but deletion of pnpA, the gene encoding polynucleotide phosphorylase (PNPase, one of the major 5′-to-3′ exonucleases that affects global mRNA turnover),12 decreases the decay rate for Class II messages without affecting the time at which decay is initiated.9 This suggests that the 3′-to-5′ exoribonuclease activity of PNPase is rate-limiting for decay of Class II mRNAs, but that a different enzyme initiates decay of these transcripts. In addition, deletion of pnpA has little effect on decay of Class I messages, indicating that PNPase is involved in distinguishing between messages of the two Classes.

Recently, RNase J1 and RNase J2 were identified in Gram+ bacteria and these enzymes have been suggested to functionally substitute for RNase E, which plays a major role in mRNA decay in Gram-bacteria.14 The J RNases both have two activities: they are the first bacterial enzymes found to have 5′-to-3′ exoribonuclease activity and in addition, they have endoribonuclease activity.14,15 Using a regulatable promoter system, we found that both RNase J1 and RNase J2 are essential for growth in GAS,10 although only RNase J1 is required for growth in Bacillus subtilis.16 We found that both J RNases affect the two Classes of GAS mRNAs, although their effects on each Class are different.10 The most dramatic effect of induction of either enzyme is alteration of the kinetics of decay for Class II mRNAs. Instead of a lag before decay initiates, upon induction of J1, decay of Class II transcripts starts immediately and proceeds with a rate similar to that seen in the wild type strain in the second phase of decay. The effect of induction of J2 is similar to that of J1, but, in keeping with the apparent requirement for less J1 than J2, the effects seen for J2 are not as great as for J1. In addition, induction of either J RNase increases the decay rate for Class I mRNAs. Thus, the J RNases appear to be involved in decay of both Classes of transcripts, but play different roles for each Class.

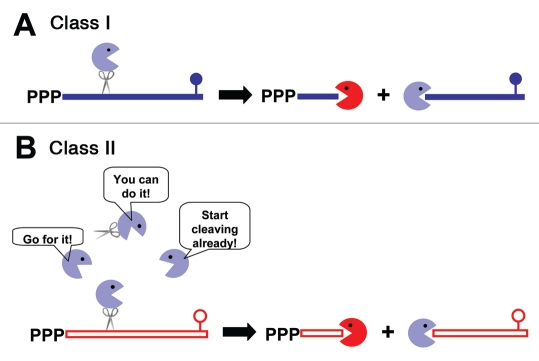

These in vivo findings led us to propose a model10 for the different pathways of decay of Class I and Class II messages in exponential phase (Fig. 1), although no biochemical analyses with purified enzymes are available yet. We proposed that Class I messages are preferred substrates for RNase J1 and J2 and that Class I mRNAs are degraded rapidly by them, using their endonucleolytic and/or their 5′-to-3′ exonucleolotic activities (Fig. 1A). We also proposed that RNase J1 and J2 have low affinity for Class II messages, and that these mRNAs are not attacked by the J RNases until the preferred substrates of these enzymes, including Class I mRNAs, are depleted. This would explain the delay in initial cleavage of Class II messages by these enzymes. We suggest that digestion of Class II mRNAs by the J RNases begins with an endonucleolytic cleavage (Fig. 1B). The detection by northern blot analysis of decay intermediates in RNase J digestion of Class II mRNAs10 is consistent with this proposal. The initiating endonucleolytic cleavage produces one fragment with a 5′-monophosphate, which is a good substrate for exonucleolytic digestion by the J RNases, and one fragment with a 3′-hydroxyl group that is sensitive to attack by 3′-to-5′ exonucleases. Although several enzymes with 3′-to-5′ exonucleolytic activity are present in GAS, it appears that PNPase plays the major role in this digestion, since decay of Class II mRNAs is slower in a PNPase deletion mutant.9

Figure 1.

Models for exponential phase mRNA decay in GAS. (A) The 5′ end of Class I mRNA (shown in blue) makes it a good substrate for RNase J1 and/or RNase J2 (blue pacman). Cleavage is most likely initiated by endonucleolytic activity of these RNases, which produces two type of products. One has an accessible 3′-end and is subject to digestion by 3′-to-5′ exonucleases (red pacman) and the other has a 5′-monophosphate which makes it a good substrate for the 5′-to-3′ exonucleolytic activity of the J RNases. (B) Class II mRNA (shown in red) is less sensitive to the J RNases, so cleavage of these mRNAs does not begin until Class I messages are depleted, freeing RNase J1 and J2 to bind to Class II mRNAs. Cleavage of Class II mRNAs is initiated endonucleolytically by the J RNases, releasing products similar to those produced from Class I mRNAs. These products are degraded 5′-to-3′ by RNase J1 and J2 and 3′-to-5′ by the 3′-to-5′ exonucleases, predominantly PNPase.

What Structural Elements of Class I and Class II mRNA in GAS Allow Ribonucleases to Distinguish between them?

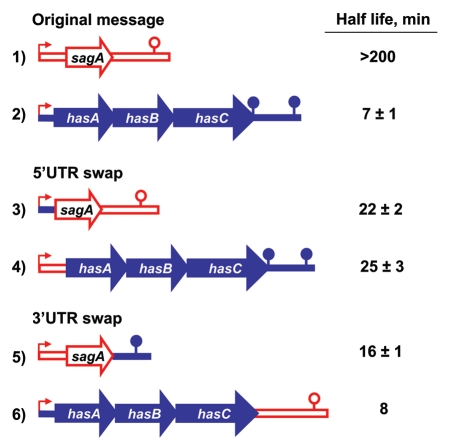

Since the 5′-end of a transcript is important for stability of messages in both Gram- and Gram+ bacteria,17,18 it seemed likely that some aspect of the structure of the 5′-untranslated region (UTR) makes Class I messages preferred substrates for RNases J1 and J2 in GAS. To study the importance of the 5′-end of a transcript in determining its sensitivity to decay, we expressed chimeric messages from Psag that contain the 5′-UTR of a Class I mRNA (has) in place of that of a Class II mRNA (sag) and vice versa. We found, using quantitative reverse transcriptase PCR (Q-RT-PCR) and northern blot analyses, that the has 5′-UTR destabilized the sag transcript in stationary phase (Fig. 2, line 3 vs. line 1), in agreement with the idea that the 5′-ends of mRNAs determine their sensitivity to the J RNases. However, the sag 5′-UTR only partially stabilized the Class I has message (Fig. 2, line 4 vs. line 2), as this chimeric transcript was less stable than the sag transcript (Fig. 2, line 4 vs. line 1). This indicates that other features of the transcript in addition to its 5′-end also affect its rate of decay. In terms of our model (Fig. 1), this might imply that some feature(s) of the 5′-end of Class I transcripts make them better substrates for the J RNases. Furthermore, our finding that an additional target within the transcript affects the rate at which it decays might indicate that decay is initiated by endonucleolytic cleavage by these enzymes.

Figure 2.

Decay rates of chimeric messages. The sag transcript is represented in red and the has transcript in blue. All transcripts are produced from Psag. The 5′-UTR begins with the transcription start, includes the ribosome binding site and ends just upstream of the translation initiation codon. The next segment starts with the translation initiation codon (AUG for sag and GUG for has), ends with the translation stop codon and comprises sagA for sag or hasABC for has. The 3′-UTR starts immediately after the translation stop codon and includes the predicted transcription pause site for sag or transcription terminator for has (lollipop). The messages were assembled using overlapping PCR and cloned under the Psag promoter (bent arrow) into plasmid pJRS9508 to generate plasmids: (1) pJRS2187; (2) pJRS1293, (3) pEU7745; (4) pEU7748; (5) pEU7753; (6) pEU7754. The chimeric constructs were expressed in the GAS strain JRS1288 (Δcov Δsag MGAS315) as described.9 GAS was grown to 1 hour into stationary phase in Todd Hewitt broth with pH adjusted to 7.5 with 100 mM HEPES, transcription was stopped by addition of rifampicin to the culture and RNA was isolated from cells collected at four to six consequent time points after rifampicin addition as described.9 The amounts for sag and has messages in each RNA sample were determined by Q-RT-PCR (four technical replicates for each sample) with primers designed to detect the middle part of the translated portion for sagA or hasA mRNA. RNA isolated from at least two independent cultures was used for Q-RT-PCR for constructs 1 to 5 and from a single culture for construct 6. Decay rates were confirmed using northern blot analysis, for constructs in lines 1, 2 and 4.

We also investigated the role of the 3′-UTR in message stability by producing chimeric transcripts from Psag. Using Q-RT-PCR, we found that the sag 3′-UTR did not stabilize the has message (Fig. 2 line 6 vs. line 2) but the has 3′-UTR destabilized the sag message (Fig. 2, line 5 vs. line 1). Therefore, although the 3′-UTR plays a role, it is not sufficient for message stabilization.

From all of our “swap” experiments, it appears that the 5′-end of the message is the most important determinant of its stability in stationary phase (i.e., the Class to which it belongs). One of the key determinants for mRNA stability in the 5′-UTR of messages of both E. coli and B. subtilis is the sequence of the ribosome binding site (RBS).19 To test whether the RBS of the sag 5′-UTR plays a role in message stabilization, we mutated it to a sequence that should not be functional in translation (AGGAGG to ACCACC). This resulted in a decrease in the half life of the sag mRNA (from > 200 min to 67 min) as determined by Q-RT-PCR, but the entire 5′-UTR sequence had a larger effect (Fig. 2, lines 3 and 4 vs. 1 and 2).

Because the J RNases in B. subtilis have a preference for monophosphorylated substrates although transcripts are produced with three phosphates on their 5′-ends,14 we thought it possible that Class I, but not Class II, mRNAs might be processed by a phosphatase to remove two of these phosphates. However, analysis by the RNA ligase mediated (RLM) assay20 demonstrated no difference between the stationary phase has and sag transcript in the fraction that was monophosphorylated (unpub).

In conclusion, the 5′-end of a message is very important in determining the Class to which it belongs, presumably by determining its susceptibility to the J RNases, but additional factors within the transcript as well as its 3′-UTR also play a role. This may suggest that the major role of the J RNases in initiating degradation of mRNAs is played by their endonucleolytic activity. Biochemical analyses of the GAS J RNases will be needed to understand the cues these enzymes use to identify substrate preference.

What Determines the Amounts of RNases J1, J2 and PNPase in GAS?

Since RNase J1, J2 and PNPase appear to be rate-limiting for Class II mRNA decay, the simplest explanation for the stability of Class II mRNAs in stationary phase is that these enzymes are absent or inactive at that phase of growth. This appears to be true for PNPase, since Q-RT-PCR for pnpA indicated that about 50 times less mRNA is present at two hours into stationary phase than in exponential phase (unpub). Further work is needed to understand the mechanism of regulation of pnpA expression in GAS.

We also found that the amounts of RNase J1 and J2 are regulated in GAS. When J2 was depleted in our conditionally expressed mutant, significantly more J1 protein was present in western blots (although this did not allow growth of the mutant, confirming that these two enzymes have different metabolic roles in GAS).10 However, somewhat surprisingly, the opposite was not true: depletion of J1 did not affect the level of J2 protein. The effect of J2 on the amount of J1 suggests that J2 may be rate-limiting for decay of J1 transcript, either directly or indirectly (through sensitivity to degradation by J2 of the message for a hypothetical protein that affects transcription or stability of J1).

Although regulation of these three critical RNases is probably responsible for the differential decay of the two Classes of messages, there is little understanding of the signal(s) to which they respond. The availability and/or activity of these RNases might be altered in response to cues like depletion of nutrients (including carbon source availability), alteration of pH, change of oxygen tension, and/or production by the bacteria of a factor or factors that accumulate in the culture medium (e.g., quorum sensing pheromones). Examples of environmental signals present in stationary phase that affect production of the products of Class II transcripts include quorum sensing21 as well as depletion of oxygen and glucose.22 This observed regulation of Class II transcription products may be indirect, at least in part, through alteration in the amounts of the J RNases and PNPase.

Signals similar to those found only at stationary phase in lab culture may occur in the host at some stage of disease progression. Transcriptome analysis showed that signals present in exponential phase in standard lab culture conditions are significantly different from those found in a murine infection model but growth of GAS in altered pH and NaCl concentration results in a transcriptome that more closely resembles that of infecting bacteria.23 Identification of signals that regulate RNases J1 and J2 and PNPase will help us understand the importance of control by mRNA decay of virulence gene expression during the different stages of infection that result in differences in disease presentation.

In conclusion, further investigation of the pathways of mRNA decay in GAS and of their regulation promises to reveal new and interesting information about the pathophysiology of this important bacterium, which is responsible for so much human disease.

Acknowledgements

We thank Alexander Schmidt for technical assistance with chimeric constructs and with Q-RT-PCR. This work was supported in part by grant RO1-20723 from the National Institutes of Health to J.R.S. and J.V.B. was partially supported by Fellowship 0725554B from the American Heart Association.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/rnabiology/article/13097

References

- 1.Cunningham MW. Pathogenesis of group A streptococcal infections and their sequelae. Advances in experimental medicine and biology. 2008;609:2942. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-73960-1_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tart AH, Walker MJ, Musser JM. New understanding of the group A Streptococcus pathogenesis cycle. Trends in microbiology. 2007;15:318–325. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2007.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carapetis JR, Steer AC, Mulholland EK, Weber M. The global burden of group A streptococcal diseases. The Lancet infectious diseases. 2005;5:685–694. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(05)70267-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martin JM, Green M. Group A streptococcus. Seminars in pediatric infectious diseases. 2006;17:140–148. doi: 10.1053/j.spid.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaplan EL, Johnson DR. Unexplained reduced microbiological efficacy of intramuscular benzathine penicillin G and of oral penicillin V in eradication of group a streptococci from children with acute pharyngitis. Pediatrics. 2001;108:1180–1186. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.5.1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu X, Shen X, Chang H, Huang G, Fu Z, Zheng Y, et al. High macrolide resistance in Streptococcus pyogenes strains isolated from children with pharyngitis in China. Pediatric pulmonology. 2009;44:436–441. doi: 10.1002/ppul.20976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hynes W. Virulence factors of the group A streptococci and genes that regulate their expression. Front Biosci. 2004;9:3399–3433. doi: 10.2741/1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kietzman CC, Caparon MG. CcpA and LacD.1 affect temporal regulation of Streptococcus pyogenes virulence genes. Infection and immunity. 2010;78:241–252. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00746-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barnett TC, Bugrysheva JV, Scott JR. Role of mRNA stability in growth phase regulation of gene expression in the Group A Streptococcus. Journal of bacteriology. 2007;189:1866–1873. doi: 10.1128/JB.01658-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bugrysheva JV, Scott JR. The ribonucleases J1 and J2 are essential for growth and have independent roles in mRNA decay in Streptococcus pyogenes. Molecular microbiology. 2010;75:731–743. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.07012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baker KE, Condon C. Under the Tucson sun: a meeting in the desert on mRNA decay. RNA. 2004;10:1680–1691. doi: 10.1261/rna.7163104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oussenko IA, Abe T, Ujiie H, Muto A, Bechhofer DH. Participation of 3′-to-5′ exoribonucleases in the turnover of Bacillus subtilis mRNA. Journal of bacteriology. 2005;187:2758–2767. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.8.2758-2767.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oussenko IA, Sanchez R, Bechhofer DH. Bacillus subtilis YhaM, a member of a new family of 3′-to-5′ exonucleases in gram-positive bacteria. Journal of bacteriology. 2002;184:6250–6259. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.22.6250-6259.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Even S, Pellegrini O, Zig L, Labas V, Vinh J, Brechemmier-Baey D, et al. Ribonucleases J1 and J2: two novel endoribonucleases in B. subtilis with functional homology to E. coli RNase E. Nucleic acids research. 2005;33:2141–2152. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mathy N, Benard L, Pellegrini O, Daou R, Wen T, Condon C. 5′-to-3′ exoribonuclease activity in bacteria: role of RNase J1 in rRNA maturation and 5′ stability of mRNA. Cell. 2007;129:681–692. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mader U, Zig L, Kretschmer J, Homuth G, Putzer H. mRNA processing by RNases J1 and J2 affects Bacillus subtilis gene expression on a global scale. Molecular microbiology. 2008;70:183–196. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06400.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sharp JS, Bechhofer DH. Effect of 5′-proximal elements on decay of a model mRNA in Bacillus subtilis. Molecular microbiology. 2005;57:484–495. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04683.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arnold TE, Yu J, Belasco JG. mRNA stabilization by the ompA 5′ untranslated region: two protective elements hinder distinct pathways for mRNA degradation. RNA (New York, NY) 1998;4:319–330. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deana A, Belasco JG. Lost in translation: the influence of ribosomes on bacterial mRNA decay. Genes & development. 2005;19:2526–2533. doi: 10.1101/gad.1348805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bensing BA, Meyer BJ, Dunny GM. Sensitive detection of bacterial transcription initiation sites and differentiation from RNA processing sites in the pheromone-induced plasmid transfer system of Enterococcus faecalis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1996;93:7794–7799. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.15.7794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Salim KY, de Azavedo JC, Bast DJ, Cvitkovitch DG. Role for sagA and siaA in quorum sensing and iron regulation in Streptococcus pyogenes. Infection and immunity. 2007;75:5011–5017. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01824-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gruening P, Fulde M, Valentin-Weigand P, Goethe R. Structure, regulation and putative function of the arginine deiminase system of Streptococcus suis. Journal of bacteriology. 2006;188:361–369. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.2.361-369.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Loughman JA, Caparon M. Regulation of SpeB in Streptococcus pyogenes by pH and NaCl: a model for in vivo gene expression. Journal of bacteriology. 2006;188:399–408. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.2.399-408.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]