Abstract

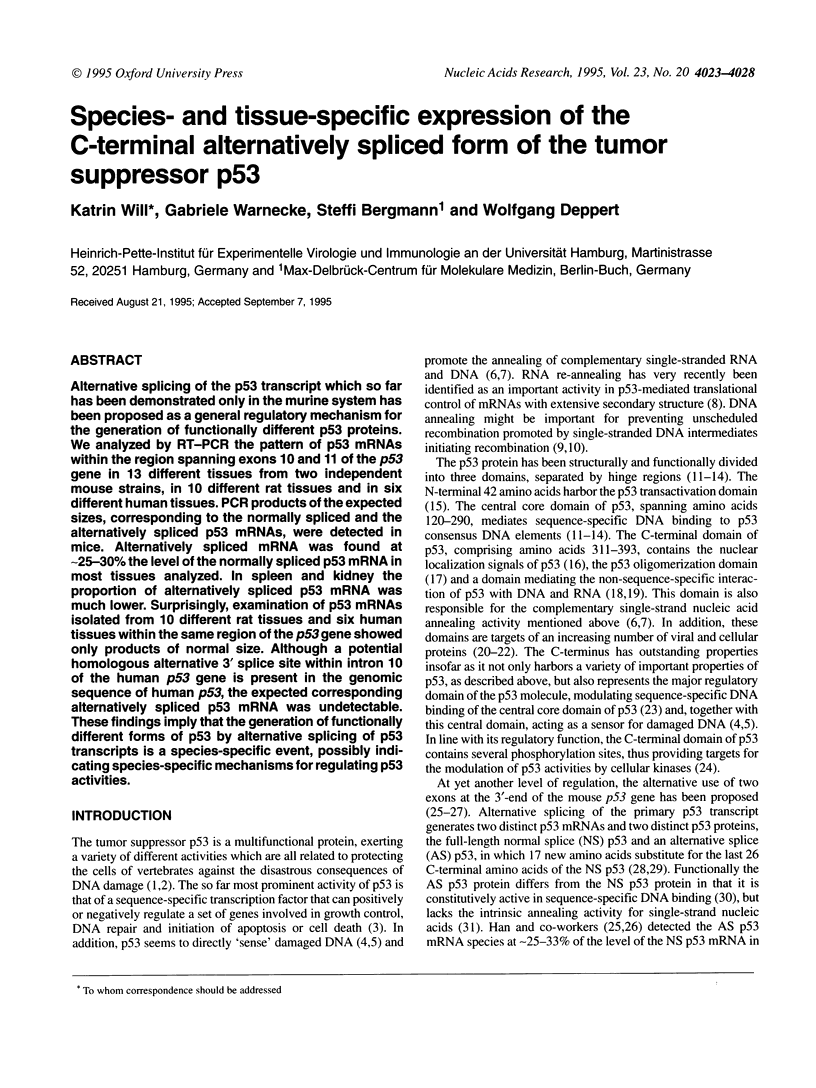

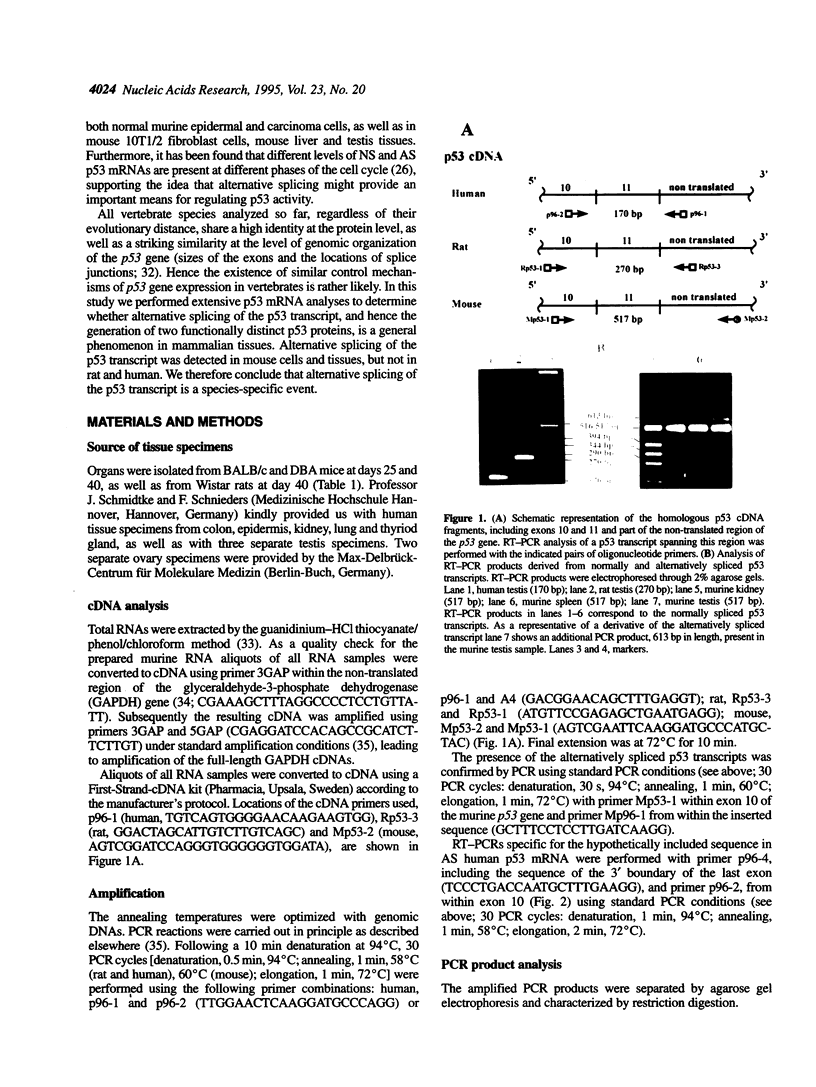

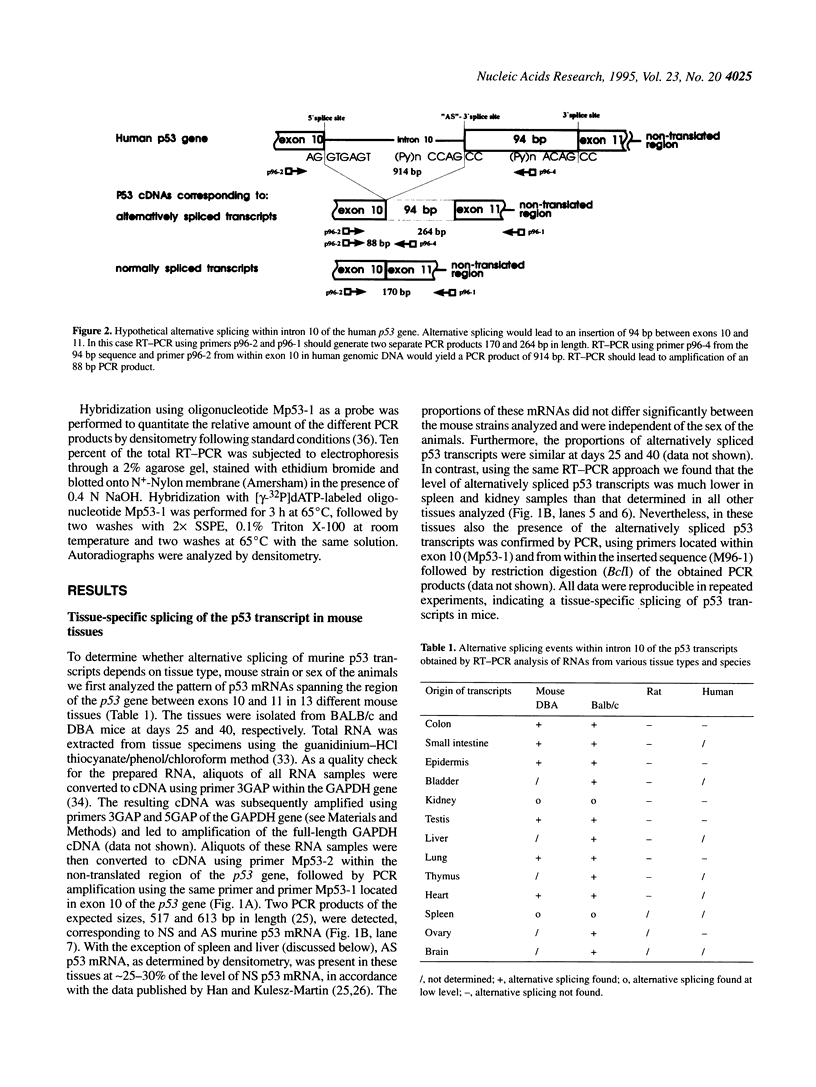

Alternative splicing of the p53 transcript which so far has been demonstrated only in the murine system has been proposed as a general regulatory mechanism for the generation of functionally different p53 proteins. We analyzed by RT-PCR the pattern of p53 mRNAs within the region spanning exons 10 and 11 of the p53 gene in 13 different tissues from two independent mouse strains, in 10 different rat tissues and in six different human tissues. PCR products of the expected sizes, corresponding to the normally spliced and the alternatively spliced p53 mRNAs, were detected in mice. Alternatively spliced mRNA was found at approximately 25-20% the level of the normally spliced p53 mRNA in most tissues analyzed. In spleen and kidney the proportion of alternatively spliced p53 mRNA was much lower. Surprisingly, examination of p53 mRNAs isolated from 10 different rat tissues and six human tissues within the same region of the p53 gene showed only products of normal size. Although a potential homologous alternative 3' splice site within intron 10 of the human p53 gene is present in the genomic sequence of human p53, the expected corresponding alternatively spliced p53 mRNA was undetectable. These findings imply that the generation of functionally different forms of p53 by alternative splicing of p53 transcripts is a species-specific event, possibly indicating species-specific mechanisms for regulating p53 activities.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Arai N., Nomura D., Yokota K., Wolf D., Brill E., Shohat O., Rotter V. Immunologically distinct p53 molecules generated by alternative splicing. Mol Cell Biol. 1986 Sep;6(9):3232–3239. doi: 10.1128/mcb.6.9.3232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakalkin G., Selivanova G., Yakovleva T., Kiseleva E., Kashuba E., Magnusson K. P., Szekely L., Klein G., Terenius L., Wiman K. G. p53 binds single-stranded DNA ends through the C-terminal domain and internal DNA segments via the middle domain. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995 Feb 11;23(3):362–369. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.3.362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bargonetti J., Manfredi J. J., Chen X., Marshak D. R., Prives C. A proteolytic fragment from the central region of p53 has marked sequence-specific DNA-binding activity when generated from wild-type but not from oncogenic mutant p53 protein. Genes Dev. 1993 Dec;7(12B):2565–2574. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.12b.2565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bienz B., Zakut-Houri R., Givol D., Oren M. Analysis of the gene coding for the murine cellular tumour antigen p53. EMBO J. 1984 Sep;3(9):2179–2183. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1984.tb02110.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brain R., Jenkins J. R. Human p53 directs DNA strand reassociation and is photolabelled by 8-azido ATP. Oncogene. 1994 Jun;9(6):1775–1780. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chomczynski P., Sacchi N. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal Biochem. 1987 Apr;162(1):156–159. doi: 10.1006/abio.1987.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox L. S., Lane D. P. Tumour suppressors, kinases and clamps: how p53 regulates the cell cycle in response to DNA damage. Bioessays. 1995 Jun;17(6):501–508. doi: 10.1002/bies.950170606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deppert W. The yin and yang of p53 in cellular proliferation. Semin Cancer Biol. 1994 Jun;5(3):187–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foord O. S., Bhattacharya P., Reich Z., Rotter V. A DNA binding domain is contained in the C-terminus of wild type p53 protein. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991 Oct 11;19(19):5191–5198. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.19.5191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gower H. J., Barton C. H., Elsom V. L., Thompson J., Moore S. E., Dickson G., Walsh F. S. Alternative splicing generates a secreted form of N-CAM in muscle and brain. Cell. 1988 Dec 23;55(6):955–964. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90241-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han K. A., Kulesz-Martin M. F. Alternatively spliced p53 RNA in transformed and normal cells of different tissue types. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992 Apr 25;20(8):1979–1981. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.8.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulla J. E., Schneider R. P. Structure of the rat p53 tumor suppressor gene. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993 Feb 11;21(3):713–717. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.3.713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hupp T. R., Meek D. W., Midgley C. A., Lane D. P. Regulation of the specific DNA binding function of p53. Cell. 1992 Nov 27;71(5):875–886. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90562-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayaraman J., Prives C. Activation of p53 sequence-specific DNA binding by short single strands of DNA requires the p53 C-terminus. Cell. 1995 Jun 30;81(7):1021–1029. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(05)80007-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krawczak M., Reiss J., Cooper D. N. The mutational spectrum of single base-pair substitutions in mRNA splice junctions of human genes: causes and consequences. Hum Genet. 1992 Sep-Oct;90(1-2):41–54. doi: 10.1007/BF00210743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulesz-Martin M. F., Lisafeld B., Huang H., Kisiel N. D., Lee L. Endogenous p53 protein generated from wild-type alternatively spliced p53 RNA in mouse epidermal cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1994 Mar;14(3):1698–1708. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.3.1698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane D. P. Cancer. A death in the life of p53. Nature. 1993 Apr 29;362(6423):786–787. doi: 10.1038/362786a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane D. P. Cancer. p53, guardian of the genome. Nature. 1992 Jul 2;358(6381):15–16. doi: 10.1038/358015a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S., Elenbaas B., Levine A., Griffith J. p53 and its 14 kDa C-terminal domain recognize primary DNA damage in the form of insertion/deletion mismatches. Cell. 1995 Jun 30;81(7):1013–1020. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(05)80006-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin J., Chen J., Elenbaas B., Levine A. J. Several hydrophobic amino acids in the p53 amino-terminal domain are required for transcriptional activation, binding to mdm-2 and the adenovirus 5 E1B 55-kD protein. Genes Dev. 1994 May 15;8(10):1235–1246. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.10.1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livingstone L. R., White A., Sprouse J., Livanos E., Jacks T., Tlsty T. D. Altered cell cycle arrest and gene amplification potential accompany loss of wild-type p53. Cell. 1992 Sep 18;70(6):923–935. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90243-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matlashewski G., Pim D., Banks L., Crawford L. Alternative splicing of human p53 transcripts. Oncogene Res. 1987 Jun;1(1):77–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberosler P., Hloch P., Ramsperger U., Stahl H. p53-catalyzed annealing of complementary single-stranded nucleic acids. EMBO J. 1993 Jun;12(6):2389–2396. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05893.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patschinsky T., Knippschild U., Deppert W. Species-specific phosphorylation of mouse and rat p53 in simian virus 40-transformed cells. J Virol. 1992 Jun;66(6):3846–3859. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.6.3846-3859.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavletich N. P., Chambers K. A., Pabo C. O. The DNA-binding domain of p53 contains the four conserved regions and the major mutation hot spots. Genes Dev. 1993 Dec;7(12B):2556–2564. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.12b.2556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietenpol J. A., Vogelstein B. Tumour suppressor genes. No room at the p53 inn. Nature. 1993 Sep 2;365(6441):17–18. doi: 10.1038/365017a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prives C., Bargonetti J., Farmer G., Ferrari E., Friedlander P., Wang Y., Jayaraman L., Pavletich N., Hubscher U. DNA-binding properties of the p53 tumor suppressor protein. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1994;59:207–213. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1994.059.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabath D. E., Broome H. E., Prystowsky M. B. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase mRNA is a major interleukin 2-induced transcript in a cloned T-helper lymphocyte. Gene. 1990 Jul 16;91(2):185–191. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(90)90087-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro M. B., Senapathy P. RNA splice junctions of different classes of eukaryotes: sequence statistics and functional implications in gene expression. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987 Sep 11;15(17):7155–7174. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.17.7155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaulsky G., Ben-Ze'ev A., Rotter V. Subcellular distribution of the p53 protein during the cell cycle of Balb/c 3T3 cells. Oncogene. 1990 Nov;5(11):1707–1711. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soussi T., Caron de Fromentel C., May P. Structural aspects of the p53 protein in relation to gene evolution. Oncogene. 1990 Jul;5(7):945–952. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stürzbecher H. W., Brain R., Addison C., Rudge K., Remm M., Grimaldi M., Keenan E., Jenkins J. R. A C-terminal alpha-helix plus basic region motif is the major structural determinant of p53 tetramerization. Oncogene. 1992 Aug;7(8):1513–1523. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Reed M., Wang P., Stenger J. E., Mayr G., Anderson M. E., Schwedes J. F., Tegtmeyer P. p53 domains: identification and characterization of two autonomous DNA-binding regions. Genes Dev. 1993 Dec;7(12B):2575–2586. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.12b.2575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Will K., Dörk T., Stuhrmann M., Meitinger T., Bertele-Harms R., Tümmler B., Schmidtke J. A novel exon in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator gene activated by the nonsense mutation E92X in airway epithelial cells of patients with cystic fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 1994 Apr;93(4):1852–1859. doi: 10.1172/JCI117172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Will K., Stuhrmann M., Dean M., Schmidtke J. Alternative splicing in the first nucleotide binding fold of CFTR. Hum Mol Genet. 1993 Mar;2(3):231–235. doi: 10.1093/hmg/2.3.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf D., Harris N., Goldfinger N., Rotter V. Isolation of a full-length mouse cDNA clone coding for an immunologically distinct p53 molecule. Mol Cell Biol. 1985 Jan;5(1):127–132. doi: 10.1128/mcb.5.1.127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu L., Bayle J. H., Elenbaas B., Pavletich N. P., Levine A. J. Alternatively spliced forms in the carboxy-terminal domain of the p53 protein regulate its ability to promote annealing of complementary single strands of nucleic acids. Mol Cell Biol. 1995 Jan;15(1):497–504. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.1.497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y., Liu Y., Lee L., Miner Z., Kulesz-Martin M. Wild-type alternatively spliced p53: binding to DNA and interaction with the major p53 protein in vitro and in cells. EMBO J. 1994 Oct 17;13(20):4823–4830. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06808.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin Y., Tainsky M. A., Bischoff F. Z., Strong L. C., Wahl G. M. Wild-type p53 restores cell cycle control and inhibits gene amplification in cells with mutant p53 alleles. Cell. 1992 Sep 18;70(6):937–948. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90244-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]