Abstract

Ostracism is ubiquitous across the lifespan. From social exclusion on the playground, to romantic rejection, to workplace expulsion, to social disregard for the aged, ostracism threatens a fundamental human need to belong that reflexively elicits social pain and sadness. Older adults may be particularly vulnerable to ostracism because of loss of network members and meaningful societal roles. On the other hand, socioemotional selectivity theory suggests that older adults may be less impacted by ostracism because of an age-related positivity bias. We examined these hypotheses in two independent studies, and tested mechanisms that may account for age differences in the affective experience of ostracism. A study of 18- to 86-year-old participants in the Time-Sharing Experiments for the Social Sciences program showed an age-related decrease in the impact of ostracism on needs satisfaction and negative affectivity. A study of 53- to 71-year-old participants in the Chicago Health, Aging, and Social Relations Study (CHASRS) showed that ostracism diminished positive affectivity in younger (<60 years) but not older adults. Age group differences in response to ostracism were consistent with the positivity bias hypothesis, were partly explained by age differences in the impact of physical pain, but were not explained by autonomic nervous system activity, computer experience, or intimate social loss or stressful life experiences.

Keywords: age, ostracism

Physical pain can be cutaneous, somatic, or visceral, but regardless of type, a common central pain network is activated (Strigo et al., 2003; Dunckley et al., 2005). Interestingly, the same central pain network that is activated during physical pain has also been implicated in the processing of social pain. Social exclusion (i.e. ostracism), bereavement, negative social comparison, and unfair treatment have each been shown to involve changes in the activity of the periaqueductal gray, thalamus, and dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (Eisenberger et al., 2004; Lieberman and Eisenberger, 2009; Takahashi et al., 2009). Moreover, the overlapping neural network underlying physical pain and social pain may also share evolutionary origins and survival functions, namely to detect threat to survival from imminent physical dangers or from absence of protective social others, respectively (Eisenberger and Lieberman, 2005).

Social pain can be defined as ‘the distressing experience arising from the perception of actual or potential psychological distance from close others or a social group’ (Eisenberger and Lieberman, 2005, p. 112). Ostracism, a word that means to ignore and exclude (Williams, 2007), is ubiquitous. Prior research has shown this to be true during the socially sensitive adolescent period (Eisenberger, 2006), but also in adulthood (Williams, 2007). The ‘silent treatment’ between close social others, workplace expulsion, teasing, being excluded or ignored in social circumstances, and countless other passive or active rejection behaviors, whether enacted for virtuous or malicious reasons, are potent elicitors of social pain (Williams, 2009). A subset of the elderly may be at special risk of exclusion as members of their cohort dwindle and family members grow distant. Moreover, the aged tend to occupy a role-less position in our society, rendering them particularly vulnerable to the pain of exclusion.

With increasing age, however, rejection experiences such as social exclusion and ostracism may have a smaller emotional impact. For instance, relative to young adults, older adults have been shown to express less negative emotionality in response to socially hurtful encounters, and to offer fewer negative appraisals and an increased likelihood of positive appraisals of the source of the hurtful comments (Charles and Carstensen, 2008). More generally, socioemotional selectivity theory posits that aging is associated with a relative advantage of positive over negative information in attention and memory (Mather and Carstensen, 2005).

Experimental approaches to studying ostracism, social exclusion, and rejection have been used since the 1960s, and have proliferated since the mid-1990s. They have largely used behavioral manipulations that involve some element of exclusion and ignoring, and manipulation checks are used to affirm that participants view the situation as such. Although a variety of behavioral manipulations have been employed (with similar patterns of results; see Williams, 2009), one of the most frequent methods employed is Cyberball (Williams et al., 2000; Williams and Jarvis, 2006), a virtual ball toss game that participants play on a computer. Participants believe they are taking part in a mental visualization exercise in which they toss a ball over the Internet with two other players. They see animated characters as proxies for themselves and the other players, and they are instructed that when they have the ball, to click one of the other players to whom they wish to throw the ball. The animated game shows the ball going from one player to another. As a cover story, participants are instructed to mentally visualize the other players, where they are playing, the weather and geography, and so on. They are even told that who gets the ball is unimportant, that all the experimenters are concerned with is that they exercise their mental visualizations. The purpose of this cover story is to makes it clear that not receiving the ball is not a sign of failing the task, so that any detrimental effects of ostracism are simply from not receiving the ball. In fact, the other two players are computer-programmed confederates, and participants are randomly assignment to one of two conditions: an inclusion condition (in which participants are thrown the ball one-third of the time) and an ostracism condition (in which the participant receives the ball only once at the beginning. These manipulations result in strong effect sizes and reported reduction in belongingness, self-esteem, control and meaningful existence. Additionally, they result in reports of pain, anger and sadness (Williams, 2009). The present paper reports the results of two studies that examine the extent to which age moderates affective responses to the social pain of ostracism as experienced in the playing of Cyberball. The second study builds on the first by also examining several candidate explanations for age differences in the affective experience of ostracism.

STUDY 1

Methods

Participants and recruiting

A representative sample of 614 White and African American adult men and women were sampled from a pool of individuals who participated in the Time-Sharing Experiments for the Social Sciences (TESS) program. The mean age of the sample was 41.0 years (s.d. = 14.5; range = 18–86 years), 49.8% were females, 51.1% were of White, non-Hispanic race/ethnicity and the balance were of Black race/ethnicity. Participants in the TESS program receive internet service via WebTV in exchange for their agreement to participate in a fixed number of studies each month. Participants in our study were initially identified as potential respondents based on previously collected demographic data; this process ensured representative sampling across ages and incomes within the population and allowed us to recruit an equal number of men and women in the White and African American racial/ethnic groups. Individuals who qualified for our study were invited to participate in a study of mental visualization that would take approximately 15 min.

Procedure

Cover story

After providing informed consent, participants were told that the goals of the research were to understand mental visualization and they would play an online game of toss with two other individuals. Participants were told that they were playing with two other same-sex individuals whose age was within 1–2 years of their own. The racial/ethnic identity and gender of the co-players was made salient by putting their names (e.g. prototypic ‘black’ names that come from the Implicit Association Test, or IAT, literature, like Tyrone, and prototypic ‘White’ names, also from the IAT literature, like Dylan) directly under the animated characters that represented the co-player. Sex was kept the same as the participant’s, and this was also represented by the names. To enhance the credibility of providing other players’ demographic information during the game, and to increase the salience of group identities, participants first responded to demographic measures of their own racial/ethnic identity, gender, and age, and were asked to provide their first names. Participants understood that this information would be shared with other players during the game; of course, in reality there were no other players, so this information remained confidential.

Cyberball

The Cyberball game used for this study was designed to be maximally involving. Full-color animated avatars wearing baseball uniforms represented the other players who were standing on what appeared to be a green field where they tossed the ball to one another’s gloves. Participants were represented on the screen by a gloved hand at the bottom of the screen, consistent with previous studies using this paradigm. Participants could see information about the other players (first name, age) in a small box that was presented immediately below each player’s avatar.

In the larger study of which this was a part, participants were randomly assigned to conditions of group context (intergroup vs ingroup) manipulated by race of coplayers; for our purposes, we collapse across group context conditions.1 Participants were randomly assigned to three levels of social inclusion (excluded, included, or over-included) via the number of times participants received the ball from other players. To avoid fatiguing participants and early drop-outs, the game was truncated to 15 total throws, and a countdown of throws was displayed. In the excluded condition, participants received the ball only twice at the beginning of the game. In the included condition, participants received the ball one-third of the time (i.e. five tosses), whereas those in the over-included condition received the ball over half of the time (seven or eight tosses). Analyses showed that the over-inclusion manipulation was not detected, so we collapsed across included and over-included conditions.2

Dependent measures

After the game, participants were presented with an initial set of items to assess our manipulations (‘What percent of the time did you receive the ball during the game?’; ‘During the game, I felt ignored.’; ‘During the game, I felt excluded.’). Responses to these last two measures were averaged such that higher scores reflected greater perceived exclusion. These measures were followed by reflexive and reflective need and affect measures, as well as attribution measures (not reported here).

Reflexive and reflective needs and affect were assessed with the same items, but the framing was altered to assess reactions during the game vs post-attribution. ‘Reflexive’ refers to the immediate, apparently pre-cognitive (as shown in affective/cognitive neuroscience measures from fMRI) reactions to the onset of ostracism (Williams, 2007, 2009). Accordingly, for the reflexive need measures, participants were instructed to indicate how they felt during the game, using a scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely). Items assessed four needs: belonging (‘I felt rejected’, ‘I felt like an outsider’), self-esteem (‘my self-esteem was high’), control (‘I felt in control’) and meaningful existence (‘I felt non-existent’, ‘I felt invisible’). Participants next responded to five affect items (good/bad; friendly/unfriendly; angry/not angry; sad/not sad; and happy/not happy). ‘Reflective’ refers to the transition to a cognitive and emotional appraisal that directs coping (Williams, 2007, 2009); accordingly, for the reflective measures, participants responded to the same set of items, but here they were instructed to respond based on how they felt ‘right now.’ Consistent with previous research (Wirth and Williams, 2009), we computed a needs index and a negative affective index for each measure by reverse-coding appropriate items and averaging across items on the scale. This resulted in reflexive and reflective needs satisfaction and negative affectivity score with higher scores reflecting greater need fulfillment and higher negative affect, respectively. To determine whether age differences in the effects of ostracism were evident for negative and positive affect, the three unipolar adjectives—happy, sad, angry (rated low to high)—were examined individually.

After completing reflexive need measures, participants were provided a summary of the research goals that included contact information for the primary investigators. Participants were encouraged to contact TESS or the PIs if they had any questions or concerns about the study; none did.

Results

Participant age was categorized to contrast young (18–25 years), middle (26–50 years), and older (51–86 years) adults. Except where noted, hypotheses regarding mean differences were tested using full-factorial General Linear Modeling (GLM) analyses with level of social inclusion and age group as between participant factors.

Manipulation checks

Feelings of exclusion were significantly stronger among participants in the excluded condition (M = 3.96, s.d. = 1.23) than among participants in the inclusion and over-inclusion conditions (M = 1.65, s.d. = 1.00), F(1,614) = 474.37, P < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.441. A significant main effect of age, F(2,614) = 11.419, P < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.036, was attributable in post hoc tests to stronger feelings of exclusion across conditions in the young group (M = 2.74, s.d. = 1.61) than in the middle (M = 2.41, s.d. = 1.50) or older group (M = 2.23, s.d. = 1.52). Age group did not significantly moderate the effectiveness of the manipulation, F(2,614) = 2.393, P = 0.092.

Age differences

Needs satisfaction index

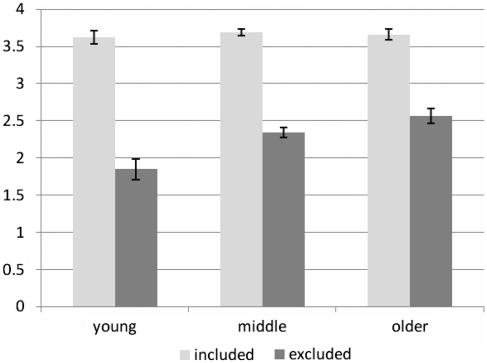

Experimental condition had a main effect on the reflexive needs satisfaction index (feelings during the game), F(1,614) = 369.544, P < 0.001. However, this effect was tempered by an interaction with age group, F (2,614) = 5.570, P = 0.004. Whereas the inclusion condition revealed no differences among age groups in degree of needs satisfaction, the ostracism condition revealed a linear increase in needs being satisfied from young, to middle, to older adults (depicted in Figure 1), which corresponds to an age-related reduction in the degree to which exclusion thwarted fundamental needs. Age differences were not evident in reflective ratings of need satisfaction (feelings now), P > 0.05.

Fig. 1.

Means (S.E.'s) for needs satisfaction index by age group in Study 1.

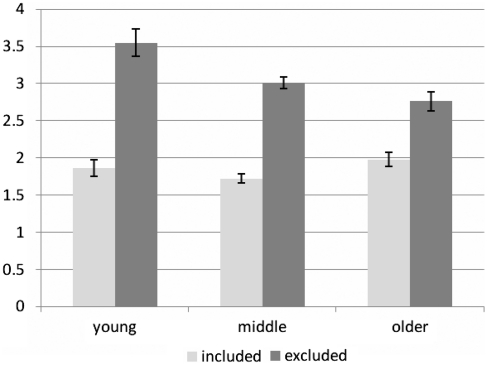

Negative affect index

Experimental condition had a main effect on the reflexive negative affect index, F(1,614) = 178.563, P < 0.001. Again, experimental condition interacted with age, F(2,614) = 6.785, P = 0.003. The inclusion condition revealed low and non-significantly different levels of negativity across the three age groups. In the ostracism condition, however, a linear decrease in negativity was observed from young, to middle, to older adults (depicted in Figure 2). A separate analysis for the reflexive positive affect item, ‘happy’, also showed an age-by-condition effect, P < 0.05, such that ostracized older individuals were more happy than their younger counterparts. Similarly, separate analyses for the reflexive negative affect items, ‘sad’ and ‘angry’, showed significant age-by-condition effects, P < 0.05, such that ostracized older individuals were less sad and angry than their younger counterparts.

Fig. 2.

Means (S.E.'s) for negative affectivity index by age group in Study 1.

As was the case for needs satisfaction, age differences were not evident in reflective ratings in which participants were asked to report their negative affect ‘right now’, P > 0.05.

Discussion

The results of Study 1 indicate that on a representative US adult sample, a brief episode of ostracism manipulated in an Internet Cyberball game was sufficient to cause a temporary reduction in feelings of belonging, self-esteem, control, and meaningful existence, as well as increased sadness and anger and decreased happiness. Furthermore, after a few minutes, these negative responses dissipated significantly. Of most importance to this report, age interacted with the initial negative responses such that older participants were reliably less affected by the ostracism experience. This was not attributable to age differences in awareness of ostracism; older participants did not differ from younger participants in their ratings of exclusion and rejection during the ostracism condition.

STUDY 2

In Study 1, age differences in response to ostracism were observed across a wide age range from young to middle-aged and older adults. Are these age differences replicable across a smaller age range of older adults? In Study 2, we sought to replicate age differences in response to Cyberball exclusion in a population-based sample of 53- to 71-year-old men and women in the Chicago Health, Aging, and Social Relations Study. Whereas Study 1 used a between-subjects design, in Study 2 we used a within-subjects design to compare feelings of acceptance and exclusion before and after ostracism. We then tested a series of competing hypotheses regarding age-related reductions in emotional responses to ostracism.

Our first hypothesis is based on socioemotional selectivity theory and posits that reduced responsivity to ostracism with age is attributable to greater attention to positive and less attention to negative affective information with increasing age (Carstensen et al., 2003). We refer to this as the positivity bias hypothesis, consistent with other research showing age-related attentional and memory biases favoring positive over negative information in older than in younger adults (Mather and Carstensen, 2005). To test this hypothesis, we expand on Study 1 by assessing both negative and positive affect in response to ostracism. Age-related reductions in the effect of ostracism on positive affect and/or negative affect would lend support to the positivity bias hypothesis.

A second reason for reduced responsivity to ostracism with age is that the CNS substrates of emotional reactivity are subject to age-related changes. The neural network that supports autonomic nervous system activity (sympathetic and parasympathetic)—autonomic nuclei in the hypothalamus and brainstem, the central nucleus of the amygdala, as well as higher cortical regions (e.g. anterior cingulate, orbitofrontal, ventromedial prefrontal, insula)—has many regions in common with the neural network that supports emotional responding, with the anterior cingulate cortex and amygdala playing a particularly important role (Critchley, 2009). To the extent that neural support for autonomic reactivity diminishes with age, cardiovascular responses to motor behavior (e.g. orthostatic challenge), cognitive effort, and emotional stimuli are also blunted (Critchley et al., 2003). We use cardiovascular responses to an orthostatic challenge as a proxy for the integrity of central control of autonomic responding. Our ANS reactivity hypothesis posits that the integrity of the ANS control network will help to explain age-related differences in emotional responses to ostracism.

Third, we consider the possibility that age differences in response to ostracism are attributable to age differences in experience with computers and the ‘high-tech’ modality in which Cyberball is played. Our computer sociality hypothesis posits that individuals with more computer experience may be more likely to treat the computer as a social entity and would therefore be expected to respond more strongly to ostracism in the Cyberball game.

A fourth reason aging may be associated with diminished responsivity to ostracism is that greater exposure to ostracism experiences over a lifetime lead to habituation. We call this the callous hypothesis to refer to the development of a social callous that prevents social pain from penetrating and threatening a sense of inclusion. Death of a child and divorce or death of a spouse may be particularly consequential social losses for the development of a social callous against ostracism. With increasing age, social losses of this magnitude are more likely to have occurred and may explain age differences in the effects of ostracism.

A fifth reason aging may be associated with diminished responsivity to ostracism (i.e. being excluded in the Cyberball game) is that physical pain that typically accompanies age-related changes in health and functional status overwhelms the social pain of ostracism. Because social pain appears to piggy-back on central neural networks that evolved for physical pain (Eisenberger et al., 2003; Lieberman and Eisenberger, 2009), there is a potential for competition among pain signals.

From a pain perspective, the contrast between potent physical pain and relatively weak social pain should be reflected in a smaller impact of ostracism. To the extent older adults experience greater physical pain, they would be expected to show smaller responses to ostracism.

A final reason for diminished responsivity to ostracism with age is that ostracism pales as a source of pain relative to a lifetime of accumulated painful experiences and threats to the satisfaction of social and other major needs. From this anchoring perspective, a long history of stressful life events may explain why older adults are less impacted by the relatively innocuous experience of exclusion from a Cyberball game. Alternatively, people may anchor their ostracism experience against ongoing chronic life stresses (e.g. financial worries, marital conflict), or against traumatic experiences in adulthood (e.g. a loved one died because of a suicide, personal injury or property damage because of a natural or manmade disaster) that continue to have emotional impact. In either case, ostracism might be expected to have minimal impact relative to these more salient and potent experiences. Age is not expected to be associated with an increased likelihood of experiencing or having experienced chronic or traumatic stress, but the impact of these experiences may explain age-related differences in responses to ostracism.

Methods

Participants

Data were collected in the Chicago Health, Aging, and Social Relations Study (CHASRS), a longitudinal, population-based study of non-Hispanic White, African American, and non-Black Latino American persons born between 1935 and 1952, and living in Cook County, IL. Participants were screened to select individuals who were competent in the English language and were sufficiently ambulatory to come to the University and participate in the study. Participants were selected to achieve an equal distribution across the six genders by racial/ethnic group combinations. Participation involves an annual day of testing in the Social Neuroscience Laboratory at the University of Chicago. Data for this study were collected in 2005, the fourth year of CHASRS. The sample size in Year 4 was 178. Of these 178, 167 completed all aspects of the Cyberball game. Participants were paid $90 for completing the daylong laboratory protocol.

The racial/ethnic distribution of the sample in Year 4 was 39% White, 34% Black, and 27% Hispanic, and ∼55% of the sample was female. Age ranged from 53 to 71 years, with a mean and median of 60 years. Approximately 62% were married or living with a partner, 20% were divorced, 10% were widowed, 3% were separated, and 5% had never been married. Ninety percent had achieved a high-school diploma or GED equivalent, and the mean number of years of schooling completed was 13.6 (s.d. = 3.0). In 2005, the modal household income category in our 53- to 71-year-old sample was $40–50K, and ∼72% of the sample reported a household income of at least $40K.

Procedure

Participants arrived at the laboratory between 8 a.m. and 9 a.m. for approximately 8 h of individual testing, including informed consent, questionnaires, interviews, and a cardiovascular protocol. The Cyberball game used for this study was a truncated, 15-throw version that represented players, including the participant, by a gloved hand, consistent with previous studies using this paradigm. Unlike Study 1, however, the Cyberball game used for this study was minimalistic; other players were represented by line drawings of black figures on a white background, and no information was presented about their names and ages. The Cyberball game was introduced by giving participants verbal instructions stating, ‘In this task we would like you to play a game with the computer. You and three other computer players will be throwing a ball to one another for a limited amount of time. When you receive the ball, you can choose which of the other three players to throw it to. To choose who to throw the ball to when it is in your possession, press the appropriate keys. (Show subject which keys to use.) When you choose whom to throw the ball to, please try to visualize actually throwing the ball to them’.

Participants played an inclusion version of the Cyberball game early in the day to orient them to the computer task modality and instruct them on the keys to use to throw the ball to one of three other players. No affective data were collected during this practice session. The 15-throw exclusion version of the Cyberball game was played ∼2 h later, at the end of a 60-min cardiovascular protocol that involved continuous monitoring of participants’ cardiovascular activity. Participants were reminded of the instructions for Cyberball, and were asked to remain quiet while playing to minimize interference with cardiovascular data collection. Immediately after receiving the game instructions, participants completed an eight-item emotion questionnaire regarding their feelings ‘right now’. Participants then completed, in sequence, a Stroop task and the Cyberball game. After playing the game, participants completed the same set of emotion items again. Finally, participants were asked how much computer experience they had.

Measures

Dependent measures

• Affect pre- and post-Cyberball

This measure consisted of eight emotion adjectives that were rated on a scale of 1–7, where 1 = not at all, and 7 = very. Four of the items were positively valenced (accepted, positive, valuable, happy), and four were negatively valenced (hurt, irritated, anxious, sad). On each occasion, pre- and post-Cyberball, participants were asked to endorse how they felt right now. Responses therefore correspond to the reflective ratings assessed in Study 1. To reduce the data, principal axis factor analyses with oblique rotation (Oblimin) were performed on the eight adjectives used to assess participants’ affective states before and after Cyberball. At each occasion, two factors emerged, one corresponding to the positively valenced adjectives, the second to the negatively valenced adjectives. Composite mean positivity ratings and mean negativity ratings were therefore calculated for each measurement occasion. Positivity and negativity ratings were correlated, r(167) = –0.24pre-cyberball and r(167) = −0.28post-cyberball.

• Autonomic Reactivity to Orthostatic Challenge

An electrocardiogram, impedance cardiogram, and blood pressure readings were obtained from each participant for 4 min while quietly sitting and 4 min while quietly standing. Cardiovascular measures of interest for the present study included systolic blood pressure (SBP) and heart rate (HR). Procedures for collecting these measures have been described elsewhere (Hawkley et al., 2006).

• Computer use

In response to the question, how many years of experience have you had using the computer, participants were given the options of <1 year, 1–2 years, and >2 years. Of 166 Cyberball participants, 63% (N = 105) reported >2 years of experience, and 30% reported <1 year of experience using a computer. In response to the question, how many hours per week, on average, do you use the computer, participants were given the options of <1 h/week, 1–7 h/week, 8–20 h/week, and >20 h/week. Of 167 Cyberball participants, the majority (64%) reported <7 h/week of computer use (38% reported <1 h/week), 14% reported 8–20 h/week, and 22% reported >20 h/week.

• Social loss

A life event checklist provided opportunity for subjects to endorse whether they had experienced the death of a spouse or child in the last year. Marital status (i.e. divorce) was ascertained from a marital history questionnaire. These questionnaires are administered annually in CHASRS. For the purposes of this study, participants were considered to have experienced a significant social loss if at any time since study onset 4 years earlier; they had lost a spouse or child to death or had divorced. Of the 154 Cyberball participants who provided data for at least one of these events, 13% (N = 20) had experienced a significant social loss.

• Physical pain

The Short Form McGill Pain Questionnaire (Melzack, 1975) was administered to participants early in the day. This questionnaire asks for pain ratings right now, on a scale where no pain = 0, mild = 1, moderate = 2, and severe = 3. Participants were asked to rate the degree to which they felt pain in general, and then to what extent the pain corresponded to each of 15 adjectives describing pain properties. Responses were summed to generate composite sensory (e.g. throbbing, shooting, cramping) and affective (e.g. tender, sickening, fearful) pain ratings as outlined in Melzack (1975). Of the Cyberball participants who provided pain data, the mean sensory pain rating was 0.20, s.d. = 0.33 (N = 155) and the mean affective pain rating was 0.13, s.d. = 0.35 (N = 152). Pain ratings were positively skewed and were subjected to a natural log transform for analytic purposes.

• Life stress

Participants completed a Life Events Questionnaire (LEQ), a 51-item checklist based on the revised social readjustment rating scale (R-SRRS; Hobson et al., 1998) that provided an opportunity to endorse whether and how often an event had occurred in the last year. We modified the R-SRRS to better suit our older sample by omitting some items (e.g. pregnancy) and adding others (e.g. retirement, loss of driver’s license). The LEQ is administered annually, and for the present study, life events were summed across the four prior years since study onset (range = 0–47). Of the 161 Cyberball participants with life event data, the mean life event count across four years was 17.1 (s.d. = 9.8), with a mode of 15 (i.e. equivalent to almost four stressful life events/year).

• Chronic stress

Using a measure of chronic stress developed by Turner et al. (1995), we asked participants to endorse whether, over the past year, they had experienced none, some, or a lot of stress stemming from eight life domains: marriage, family, social life, work, financial problems, residential/neighborhood concerns, the health of close others and general sources (e.g. ‘too much is expected of you by others’). For the purposes of the present study, responses were dichotomized (yes/no) and the number of domains that received an endorsement were summed to generate a total chronic stress score (range = 0–8). Of 167 Cyberball participants, the mean number of domains in which chronic stress was experienced was 5.3 (s.d. = 1.9), with the majority of the sample (73%) reporting chronic stress in five or more domains.

• Traumatic events

The occurrences of trauma (e.g. being a victim of crime, surviving a disaster) were obtained by tabulating participants’ responses to a revised version of the Lifetime Trauma Schedule (Turner et al., 1995), in which participants were instructed to report traumas that happened in the 12 months prior to the interview. For present purposes, traumas reported during the four years since study onset were summed to generate a total adult trauma score (range = 0–9). Of 163 Cyberball participants, the mean number of traumatic events experienced over the four-year period was 2.76 (s.d. = 2.36). The modal response was 2, and 58% of the sample reported two or fewer traumas in the prior 4 years.

Results

Participant age was categorized to contrast those below the median age of 60 (N = 88) with those 60 years and older (N = 79). Except where noted, hypotheses regarding mean differences were tested using mixed-factorial General Linear Modeling (GLM) analyses with pre- and post-Cyberball as a within-subject factor, age group as a between-subject factor, and explanatory variables as covariates. For covariates that moderated the pre- to post-Cyberball effect, we assessed the degree to which the interaction explained age differences in responses to Cyberball.

Age differences in ostracism: replication and explanation

Positivity bias hypothesis: do older adults show smaller negative emotional responses to ostracism than young adults?

Neither positivity nor negativity composite ratings showed a main effect in response to the Cyberball task, F’s(1,165) < 2.2, P’s > 0.1, but age group moderated the within-subject changes in positivity ratings, F(1,165) = 5.37, P = 0.022. The younger group showed a decrease in positivity after Cyberball ostracism (Mpre-Cyberball = 5.82, s.e. = 0.10, Mpost-Cyberball = 5.71, s.e. = 0.11), and the older group showed a slight increase in positivity (Mpre-Cyberball = 5.96, s.e. = 0.11, Mpost-Cyberball = 6.08, s.e. = 0.12). Regression parameters corresponding to these means indicated that younger adults did not differ from older adults in pre-Cyberball levels of positivity, B = −0.14, s.e. = 0.15, P > 0.3, but exhibited significantly lower levels of positivity after Cyberball than did older adults, B = −0.37, s.e. = 0.17, P < 0.05.

Autonomic reactivity hypothesis: does compromised autonomic control explain reduced effects of ostracism with age?

Mixed-factorial GLM analyses (within: sitting, standing; between: age group) revealed that the orthostatic challenge elicited significant increases in SBP (Msitting = 129.1, s.d. = 15.0; Mstanding = 138.5, s.d. = 18.2), F(1,160) = 93.351, and HR (Msitting = 63.8, s.d. = 10.8; Mstanding = 74.2, s.d. = 13.0), F(1,161) = 653.45, P’s < 0.001. However, there were no main effects of age on SBP, P’s > 0.3, and interactions between posture and age were non-significant, P’s > 0.2. The absence of age differences in ANS responses to a postural change suggest that individual differences in the integrity of central ANS control networks are not a plausible explanation for age differences in responses to ostracism in our cohort of 53- to 71-year-olds.3

Computer sociality hypothesis: does lack of computer experience explain reduced effects of ostracism with age?

The younger and older age groups did not differ in years of computer experience (Myounger = 2.4, s.d. = 0.9; Molder = 2.3, s.d. = 0.9), F < 1, P > 0.3, or in hours per week of computer use (Myounger = 2.3, s.d. = 1.2; Molder = 2.1, s.d. = 1.1), F = 1.2, P > 0.2. Mixed-factorial GLM analyses revealed no main effect of computer experience or use on the positivity index, P’s > 0.6, and no moderating influence of computer experience or use on changes in positivity in response to ostracism, P’s > 0.2. This evidence fails to support the notion that the computer mode of task delivery contributed to age differences in responses to Cyberball ostracism.

Social callous hypothesis: does a history of social loss explain reduced effects of ostracism with age?

A chi-square test showed a nonsignificantly greater prevalence of intimate social loss (i.e. death of child or death/divorce of spouse) in the older (16%) than the younger age group (10%), χ2 (1) = 1.31, P > 0.2. A mixed-factorial GLM analysis showed that having suffered an intimate social loss had no main effect on the positivity response to Cyberball, P > 0.4, and did not interact with game period to influence positivity ratings, P > 0.2. These findings fail to support the notion that prior social losses lead to desensitization to the impact of the social pain of Cyberball ostracism.

Pain perspective: does the presence of physical pain explain reduced effects of ostracism with age?

Approximately 77% of the sample experienced no affective pain, and the sample as a whole reported low levels of affective pain (M = 0.11, range = 0–2.25). In contrast, only 53% of the sample reported no sensory pain, and the average level was 0.18 (range = 0–2). Univariate analyses of variance revealed no age differences in general, sensory, and affective pain levels at the start of participants’ day in the laboratory, F’s < 1.6, P’s > 0.2. Consistent with the notion of competition between physical pain and the social pain of ostracism, ratings of sensory pain (i.e. throbbing, shooting, cramping) reported by participants early in the day were inversely correlated with changes in the composite negativity index of response to ostracism later in the day (r = −0.162, P < 0.05); the correlation with the composite positivity index did not achieve statistical significance (r = −0.07, P > 0.3).

Mixed-factorial GLM analyses revealed that each of the types of physical pain exhibited a main effect on positivity ratings, P’s < 0.01. In addition, affective pain, but not general or sensory pain, interacted with game period, F(1,149) = 7.22, P < 0.01, to moderate the impact of Cyberball ostracism on the positivity index. The addition of this interaction term to the GLM modestly attenuated the age difference in the impact of ostracism, F(1,149) = 3.85, P = 0.052. Regression parameters corresponding to age differences in positivity indicated non-significant effects of affective pain on pre-Cyberball positivity ratings, and a smaller decrease in positivity among the younger than the older adults post- Cyberball, from B = −0.31, SE = 0.18, P = 0.09, to B = −0.22, SE = 0.17, P = 0.18. In other words, the older adults no longer showed significantly reduced effects of ostracism relative to the younger adults when affective pain was held constant.

Affective pain ratings may be subject to a neuroticism-related response bias that accounts for the reduction in the response to ostracism. To determine whether neuroticism might explain the moderating influence of affective pain, we added a measure of neuroticism to the model as a covariate. Neuroticism had a main effect on positivity ratings pre- and post-Cyberball ostracism, but affective pain maintained an independent effect on positivity ratings and, when neuroticism was held constant, the impact of affective pain on age differences in positivity remained virtually unchanged, B = −0.22, S.e. = 0.16, P = 0.18.

Anchoring hypothesis: does a history of life stress explain reduced effects of ostracism with age?

• Life events

A univariate analysis of variance showed that the younger age group had experienced significantly more stressful life events during the past 4 years than the older group, Myounger = 19.0 (s.e. = 1.2), Molder = 15.0 (s.e. = 1.0), F(1,165) = 7.06, P < 0.01. A mixed-factorial GLM analysis showed that number of life events had no main effect on the positivity response to Cyberball, P > 0.1, and did not interact with game period to influence positivity ratings, P > 0.2.

• Chronic stress

A univariate analysis of variance showed that the younger age group was experiencing more types of chronic stress at the time of testing than the older group, Myounger = 5.6 (s.e. = 1.8), Molder = 5.0 (s.e. = 2.1), F(1,165) = 4.79, P < .05. A mixed-factorial GLM analysis showed that chronic stress had a main effect in reducing positivity, F(1,164) = 8.11, P < 0.01, and a nonsignificant interaction term indicated that chronic stress did not alter changes in positivity in response to ostracism, P > 0.7.

• Trauma

Analyses of variance showed no age group differences in adult traumas experienced over the past 4 years, F < 2.6, P > 0.1. A mixed-factorial GLM analysis showed that adult trauma had neither a main effect nor an interactive effect on positivity responses to ostracism, P’s > 0.1. In summary, none of our measures of life stress explained age differences in positivity responses to Cyberball ostracism, and the anchoring hypothesis remains unsupported.

GENERAL DISCUSSION

In two independent studies, we found that the pain of ostracism was less intense in older than in younger adults. The first study used a between-subject design to test a wide age range of adults and showed that the ostracism condition but not the inclusion condition of Cyberball elicited a linear decrease in negative affect, a corresponding increase in positive affect, and a smaller decrement in frustration of needs satisfaction from young (18–25 years), to middle (26–50 years), to older adults (51–86 years). The second study used a within-subject design to test a smaller age range of 53- to 71-year-old adults and replicated the diminution of the effect of ostracism on affect in older adults. These results are consistent with the positivity bias hypothesis in showing an age-related decrease in the impact of negatively valenced social information (i.e. social exclusion). Ostracism elicited a decrease in positivity in the relatively young (i.e. those under the median age of 60 years) that was not evident in the relatively older adults (60 years of age or older). Negativity ratings were not differentially associated with age in this sample.

We investigated five additional mechanisms that we posited might explain the age-related reduction in response to ostracism, and found only limited support for a role of physical pain in explaining age differences in emotional responses to ostracism. Across the age range, affective ratings of physical pain diminished the effect of ostracism on positivity ratings; greater affective pain was associated with smaller decrements in positivity in response to ostracism. Moreover, affective pain moderated the impact of ostracism. Although affective pain ratings did not differ with age, affective pain reduced the age difference in response to ostracism. This effect could not be explained by response bias associated with neuroticism. Contrary to expectations, however, the younger and not the older group showed the effect of physical pain on responses to social pain. Smaller decreases in positivity after ostracism in the younger relative to the older group may reflect a more profound psychological impact of physical pain which may wane as it becomes an inevitable part of their daily lives. Thus, for younger adults more so than older adults, these results are consistent with the hypothesis that physical pain serves as a reference point against which social pain appears much less intense. Whether this effect holds true across the lifespan is a question for further research.

Alternatively, older adults may find social tasks more burdensome or aversive, and their slight increase in positive affect in response to ostracism may be the consequence of being relieved that they didn’t have to respond to others and make a decision about to whom to throw the ball. We note, first, that older participants in Study 1 did not like being ostracized, just that their dislike was not as strong as in their younger counterparts. Second, if older adults find social tasks more burdensome, then one might expect that they also find demanding social relationships more burdensome than do young adults. We tested this hypothesis in ancillary analyses using data from CHASRS participants and found that neither the intensity of demands imposed by social network members, nor the ratio of resources to demands, differed as a function of age group. In addition, relationship demands did not moderate the impact of age group on responses to ostracism. Additional research is needed to determine the extent to which ‘social relief’ contributes to diminished emotional responsivity to ostracism.

Autonomic nervous system activity did not differ as a function of age in our sample, and thus could not explain age-related reductions in response to ostracism. We tested a limited age range, however, and it is possible that decrements in ANS arousability with age explain decreases in ostracism across the adult lifespan. Additional research is needed to test this possibility.

We expected to find age differences in years of computer experience or in weekly hours of use. Although mean age group differences were in the expected direction, the effect was not significant in our sample of 53- to 71-year-old adults, and therefore was not a viable explanation for age differences in response to ostracism. Research to date has consistently found decreased computer and Internet use with increased age (Fox, 2001; Cutler et al., 2003). This difference is largely attributable to the absence of computers in the homes of older adults, especially those who are no longer part of the work force (Cutler et al., 2003; U.S. Department of Commerce, 2004). We suspect that the computer mode of social interaction, as was represented in the Cyberball game, will be of diminishing relevance for age differences as information technology tools become increasingly prevalent in households and more frequently used by older adults. Nevertheless, regardless of age, unmeasured attitudes toward technological tools may be found to influence attitudes toward and responses to virtual social interactions (Cutler et al., 2003). Notably, Study 2 consisted of a population-based sample of older adults, so our results cannot simply be explained in terms of sample selection bias.

We expected and found greater prevalence of intimate social loss in our relatively older group.

In addition, we found greater prevalence of chronic stress in the younger than the older group.

However, neither the numbing or callousing effect of prior social pain nor the anchoring function of chronic or intense life stress accounted for age differences in response to ostracism. Additional research should examine whether social losses cumulate to take a toll on responses to social exclusion in oldest old age.

On the other hand, to the extent that social networks diminish with age, older adults may increasingly focus on close social partners and be less concerned about being excluded by strangers.

Ancillary analyses of the CHASRS data did not reveal an age difference in social network size and network size did not moderate the age effect on positivity responses to ostracism. Whether the oldest members of our society become sensitized or desensitized to exclusionary cues as they lose spouses, friends, and family members, remains an open question. The positivity bias exhibited with increasing age stands as a hopeful sign for an aging society, but additional work is needed to examine whether the benefits of this adaptive bias extend into oldest old age.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was funded by the National Institutes on Aging under Program Project Grant No. PO1 AG18911 and RO1 AG034052-01 to JTC, and R01-AG036433 to L.C.H.; by an award from the Templeton Foundation to J.T.C.; and by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. 0519209 to K.D.W. Computer programming and data collection were awarded to Stephanie A. Goodwin and K.D.W. by the Time-sharing Experiments for the Social Sciences, NSF Grant 0818839 to Jeremy Freese and Penny Visser. The authors would like to thank Adrienne Carter-Sowell for her assistance with the analyses for Study 1.

Footnotes

1Intergroup manipulations had effects on the delayed reflective responses, not the reflexive responses, but these are the subject matter of another submission (still under review) by a different group of authors.

2Over-inclusion was not distinguishable from inclusion in our abbreviated 15-throw game. Other studies (Williams et al., 2000) used a 30-throw game and showed recognition of, and positive feelings resulting from over-inclusion.

3Although autonomic reactivity to ostracism reflects both the integrity of central neural control of the ANS and affect-specific reactions, we also examined ‘context-specific’ (i.e. ostracism) ANS reactivity. We did not find age differences in SBP or HR reactivity to Cyberball ostracism (P’s > 0.1), nor did cardiovascular reactivity moderate the association between age and affective responses to ostracism.

REFERENCES

- Carstensen LL, Fung HH, Charles ST. Socioemotional selectivity theory and the regulation of emotion in the second half of life. Motivation and Emotion. 2003;27:103–23. [Google Scholar]

- Charles ST, Carstensen LL. Unpleasant situations elicit different emotional responses in younger and older adults. Psychology and Aging. 2008;28:495–504. doi: 10.1037/a0013284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Critchley HD. Psychophysiology of neural, cognitive and affective integration: fMRI and autonomic indicants. International Journal of Psychophysiology. 2009;73:88–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2009.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Critchley HD, Mathias CJ, Josephs O, et al. Human cingulated cortex and autonomic control: converging neuroimaging and clinical evidence. Brain. 2003;126:2139–52. doi: 10.1093/brain/awg216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutler S J, Hendricks J, Guyer A. Age differences in home computer availability and use. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2003;58:S271–80. doi: 10.1093/geronb/58.5.s271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunckley P, Wise RG, Fairhurst M, et al. A comparison of visceral and somatic pain processing in the human brainstem using functional magnetic resonance imaging. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2005;25:7333–41. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1100-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberger NI. Identifying the neural correlates underlying social pain: implications for developmental processes. Human Development. 2006;49:273–93. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberger NI, Lieberman MD. Why it hurts to be left out: the neurocognitive overlap between physical and social pain. In: Williams KD, Forgas JP, von Hippel W, editors. The Social Outcast: Ostracism, Social Exclusion, Rejection, and Bullying. NY: Psychology Press; 2005. pp. 109–27. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberger NI, Lieberman MD, Williams KD. Does rejection hurt? An fMRI study of social exclusion. Science. 2003;302:290–2. doi: 10.1126/science.1089134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox S. Wired seniors: a fervent few, inspired by family ties. Pew Internet American Life Project. 2001 Available at: http://www.pewinternet.org/∼/media/Files/Reports/2001/PIP_Wired_Seniors_Report.pdf.pdf (date last accessed May 17, 2010) [Google Scholar]

- Hawkley LC, Masi CM, Berry JD, Cacioppo JT. Loneliness is a unique predictor of age-related differences in systolic blood pressure. Psychology and Aging. 2006;21:152–64. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.21.1.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobson CJ, Kamen J, Szostek J, Nethercut CM, Tiedmann JW, Wojnarowicz S. Stressful life events: a revision and update of the social readjustment rating scale. International Journal of Stress Management. 1998;5:1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman MD, Eisenberger NI. Pains and pleasures of social life. Science. 2009;323:890–1. doi: 10.1126/science.1170008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mather M, Carstensen LL. Aging and motivated cognition: the positivity effect in attention and memory. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2005;9:496–502. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2005.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melzack R. The McGill Pain Questionnaire: major properties and scoring methods. Pain. 1975;1:277–99. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(75)90044-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strigo IA, Duncan GH, Boivin M, Bushnell MC. Differentiation of visceral and cutaneous pain in the human brain. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2003;89:3294–303. doi: 10.1152/jn.01048.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi H, Kato M, Matsuura M, Mobbs D, Suhara T, Okubo Y. When your gain is my pain and your pain is my gain: neural correlates of envy and schadenfreude. Science. 2009;323:937–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1165604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner R J, Wheaton B, Lloyd DA. The epidemiology of social stress. American Sociological Review. 1995;60:104–25. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration, National Telecommunications and Information Administration. A nation online: entering the broadband age. 2004 Retrieved June 4, 2009, from http://www.ntia.doc.gov/reports/anol/NationOnlineBroadband04.htm#_Toc78020933. [Google Scholar]

- Williams KD. Ostracism. Annual Review of Psychology. 2007;58:425–52. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams KD. Ostracism: a temporal need-threat model. In: Zanna M, editor. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. Vol. 41. New York: Academic Press; 2009. pp. 279–314. [Google Scholar]

- Williams KD, Cheung CKT, Choi W. CyberOstracism: effects of being ignored over the Internet. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;79:748–62. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.79.5.748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams KD, Jarvis B. Cyberball: a program for use in research on ostracism and interpersonal acceptance. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, and Computers. 2006;38:174–80. doi: 10.3758/bf03192765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wirth JH, Williams KD. ‘They don't like our kind’: consequences of being ostracized while possessing a group membership. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations. 2009;12:111–27. [Google Scholar]