Abstract

A method for the enantioselective synthesis of biphenols from readily prepared 1,4-diketones is reported. Key to the success of this method is the highly selective transfer of central to axial chirality during a double aromatization event triggered by BF3•OEt2. Based upon X-ray crystallographic data, a stereochemical model for this chirality exchange process is put forth.

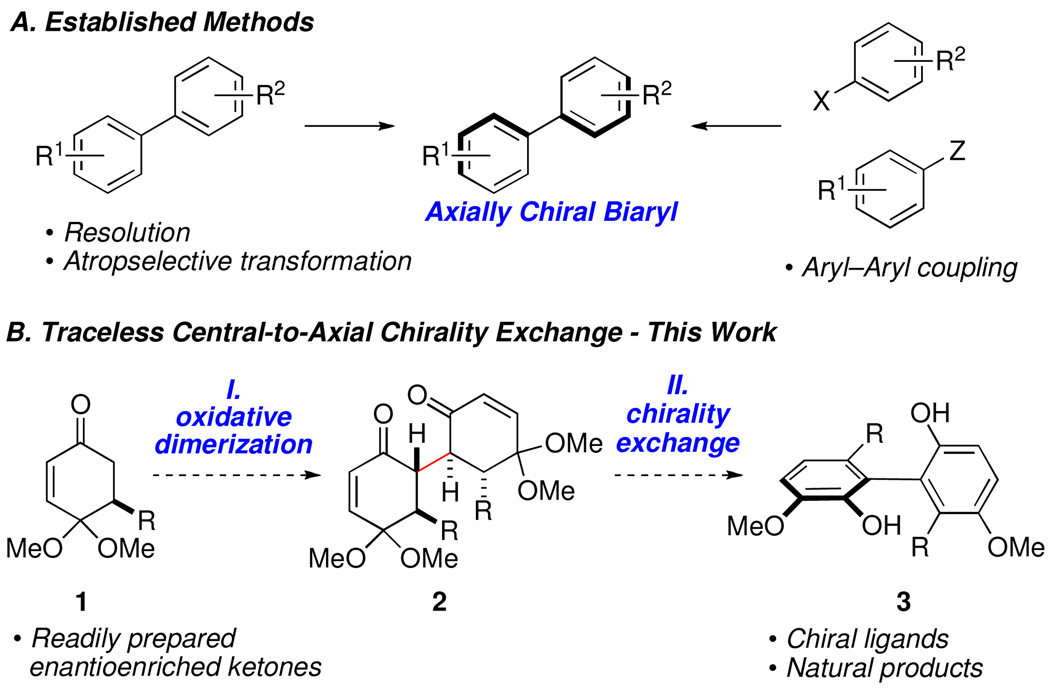

Axially chiral biaryls are an important class of molecules due to their widespread use in asymmetric catalysis, and because many biologically active natural products contain biaryl linkages.1 Typical methods for enantioselective biaryl synthesis involve direct asymmetric coupling,2 or atropselective transformation of preformed aromatic rings (Figure 1A).3 As a consequence of our investigations into the synthesis of 1,4-diketones,4 we speculated that linked bicyclic compounds such as dione 2 (Figure 1B) might aromatize with efficient central-to-axial chirality exchange due to restricted rotation about their central carbon–carbon bond.5,6 Because the sp3 stereogenic centers that impart chirality in the dione precursor are simultaneously destroyed during the creation of the biaryl axis, we consider such transformations to involve “traceless” stereochemical exchange.7 Such reactions may thus be considered distinct from related methods for atroposelective synthesis that rely upon external control elements that are removed or destroyed in a separate synthetic manipulation after formation of the stereogenic axis.8,9

Figure 1.

Chirality exchange based synthesis of biphenols

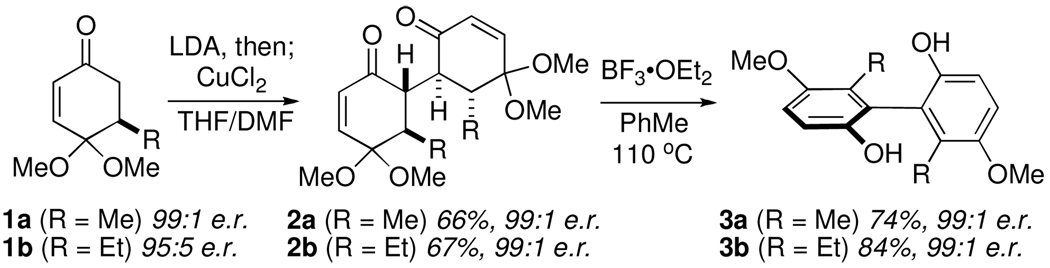

In this communication, we report the successful implementation of traceless stereochemical exchange for the synthesis of a biphenols, arguably the most important class of axially chiral compounds. Our study began with enones 1a and 1b, which were accessed by the enantioselective conjugate addition of dimethyl- or diethylzinc to the corresponding achiral dimethylketal quinone, using the method reported by Feringa and coworkers.10 After investigating a number of reported conditions for oxidative dimerization of ketones, we found that the conditions reported by Saegusa and coworkers in 1975 provided the greatest yield of the desired dimeric 1,4-diketones (Scheme 1).11 Thus, treatment of ketone 1a with LDA followed by the addition of copper(II) chloride allowed the formation of 2a in 66% yield (99:1 e.r.). In contrast to the monomer 1a, which readily aromatized in the presence of Lewis acids, dione 2a proved remarkably stable under a variety of conditions, most likely due to the high degree of steric congestion imparted by the four contiguous stereocenters. Ultimately, we found that exposure of 2a to excess BF3•OEt2 in toluene at reflux gave the desired biaryl 3a smoothly and in good chemical yield. More importantly, complete transfer of chirality from 2a was observed, with biaryl 3a formed in a 99:1 ratio of enantiomers. The same outcome was observed when enone 1b was subjected to the identical sequence (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

Initial development of biaryl synthesis

With the validity of this concept established, we wished to expand the range of potential substrates to include enones that possessed β-aryl groups. To achieve this goal, we developed a modified variant of the system reported by Hayashi and coworkers for the rhodium-catalyzed 1,4-addition of arylzinc species to 2,3-dihydro-4-pyridones.12 We found that in the presence of TMSCl, [RhCl((R)-BINAP)]2 catalyzed the conjugate addition of a range of arylzinc reagents to enone 4 to first provide the corresponding enol silanes, which after workup and purification afforded the desired enones (i.e., 5) in high yield and with good levels of enantioselectivity (Table 1). Oxidative dimerization of the β-aryl substituted enones proceeded readily under the copper(II) chloride promoted conditions we had used previously for the aliphatic substrates (Table 1). Reasonable yields were obtained for the synthesis of these highly congested 1,4-diketones (i.e., 6), which were isolated as single diastereomers with enantiomeric ratios of at least 99:1 for all cases despite the lower enantiopurity of the individual monomers. Such enhancement of enantiopurity was an expected outcome for this process based on Horeau’s amplification of chirality principle.13 That is to say, the minor monomeric enantiomer is removed through formation of a diastereomeric dione that can be separated by conventional chromatography. Aromatization of the diones proceeded smoothly and with complete stereochemical transfer upon exposure to BF3•OEt2, providing the biphenol compounds (i.e., 7) in high yield.

Table 1.

Enantioselective synthesis of biphenols: Rh-catalyzed 1,4-addition/oxidative coupling/aromatization sequence

| entry | Ar | yield 5 (%)a | e.r. 5b | yield 6 (%)a | e.r. 6b | yield 7 (%)a | e.r. 7b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ph (5a) | 89 | 94:6 | 56 (80) | 99:1 | 77 | 99:1 |

| 2 | 2-Naphthyl (5b) | 87 | 94:6 | 51 (78) | 99:1 | 82 | 99:1 |

| 3 | 4-OMe-Ph (5c) | 92 | 94:6 | 50 (70) | 99:1 | 86 | 99:1 |

| 4 | 4-Me-Ph (5d) | 90 | 94:6 | 63 (74) | 99:1 | 89 | 99:1 |

| 5 | 4-F-Ph (5e) | 88 | 96:4 | 66 (74) | 99:1 | 88 | 99:1 |

| 6 | 3,5-di-Me-Ph (5f) | 90 | 92:8 | 73 (81) | 99:1 | 85 | 99:1 |

| 7 | 3,5-di-OMe-Ph (5g) | 89 | 95:5 | 48 (69) | 99:1 | 75 | 99:1 |

| 8 | 3,4-methylenedioxy-Ph (5h) | 80 | 95:5 | 52 (74) | 99:1 | 78 | 99:1 |

Isolated yield after chromatography. Numbers reported in parenthesis refer to yields based on recovered starting material.

Determined by HPLC.

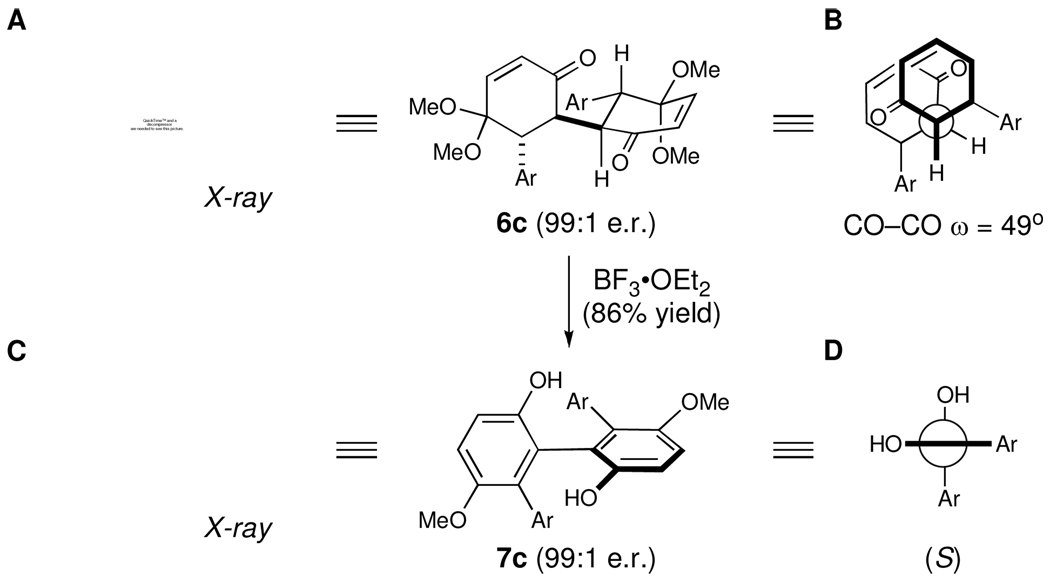

The absolute and relative configuration of dione 6c (A in Figure 2) was confirmed through X-ray crystal structure analysis using anomalous dispersion from a copper-source X-ray diffractometer.14,15 As anticipated, oxidative dimerization proceeded such that the newly forged carbon–carbon bond formed anti to the β-substituent. The dione 6c adopts a conformation wherein each substituent is equatorially disposed, and where the dihedral angle (ω) between the carbonyl carbon atoms is approximately 49°. A Newman projection drawn along the central carbon–carbon bond between each ring may therefore be approximated by structure B (Figure 2), such that the carbonyl groups are in a gauche relationship. If aromatization now occurs from this conformation without rotation about the central carbon–carbon bond, then the product thus obtained should possess the (S)-absolute configuration. X-ray structural analysis of biphenol 7c confirmed this assignment. Similarly, biphenol 3a (Scheme 1) was shown to possess the (R)-configuration, which is consistent with the proposed model (Figure 2) given that the absolute configuration of the monomeric enone 1a precursor is (R).15 Therefore, it appears that given an enone of known configuration, one should be able to reliably predict the configuration of a chiral axis formed through this traceless stereochemical exchange process.

Figure 2.

Stereochemical model (Ar = 4-MeO-Ph)

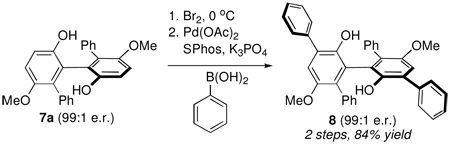

The biphenols prepared herein may prove useful for future synthetic applications. For example, we have demonstrated that biaryl 7a may be dibrominated with complete regioselectivity ortho to the free phenolic group, and that subsequent elaboration to the extended biphenol structure 8 can be achieved through the use of a palladium-catalyzed Suzuki cross-coupling reaction (eq. 1).16 Such extended biphenols may provide unique building blocks for the development of novel ligands for asymmetric catalysis akin to the “vaulted” BINOL ligands (i.e., VAPOL and VANOL) introduced by Wulff and coworkers.17

|

(1) |

In conclusion, we have devised an effective method for the enantioselective construction of biaryl compounds through traceless central-to-axial chirality exchange that has provided a range of chiral biphenols with high levels of enantiopurity. Furthermore, in order to expand the diversity of substrates available for this method, we developed an enantioselective rhodium-catalyzed addition of arylzinc reagents to achiral dimethylketal quinones, which should find application beyond the chemistry described herein. Current research efforts are focused on applying this concept of traceless chirality exchange to the synthesis of biologically active natural products and novel ligands for asymmetric catalysis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

Support for this work was provided by Northwestern University (NU) and the NIH/NIGMS (1R01GM085322). We thank Kiel Lazarski (NU) and Dr. Amy Sargeant (NU) for assistance in X-ray structure analysis.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Detailed experimental procedures and spectral data for all compounds. This material is available free of charge via the internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.For recent reviews, see: Kozlowski MC, Morgan BJ, Linton EC. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009;38:3193–3207. doi: 10.1039/b821092f. Bringmann G, Mortimer AJP, Keller PA, Gresser MJ, Garner J, Breuning M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005;44:5384–5427. doi: 10.1002/anie.200462661. Wallace TW. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2006;4:3197–3210. doi: 10.1039/b608470m. Baudoin O. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2005:4223–4229. Hassan J, Sévignon M, Gozzi C, Schulz E, Lemaire M. Chem. Rev. 2002;102:1359–1469. doi: 10.1021/cr000664r..

- 2.For general reviews, see: Bolm C, Hildebrand JP, Muñiz K, Hermanns N. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2001;40:3284–3308. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20010917)40:18<3284::aid-anie3284>3.0.co;2-u. Whiting DA. In: Comprehensive Organic Synthesis. Trost BM, Fleming I, Pattenden G, editors. vol. 3. Oxford: Pergamon; 1991. p. 659. For a recent report, see: Shen X, Jones GO, Watson DA, Bhayana B, Buchwald SL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:11278–11287. doi: 10.1021/ja104297g.. See also reference 1.

- 3.For example, the “lactone concept” developed by Bringmann and coworkers, see: Bringmann G, Breuning M, Pfeifer R-M, Schenk WA, Kamikawa K, Uemura M. J. Organomet. Chem. 2002;661:31–47. Bringmann G, Menche D. Acc. Chem. Res. 2001;34:615–624. doi: 10.1021/ar000106z. Miller and coworkers recently reported a fascinating peptide-catalyzed dynamic kinetic resolution of biaryl atropisomers, see: Gustafson JL, Lim D, Miller SJ. Science. 2010;328:1251–1255. doi: 10.1126/science.1188403..

- 4.Avetta CT, Konkol LC, Taylor CN, Dugan KC, Stern CL, Thomson RJ. Org. Lett. 2008;10:5621–5624. doi: 10.1021/ol802516z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lucchi and coworkers similarly speculated that the dimer of carvone might be converted to an enantioenriched biaryl. Unfortunately, they were unable to successfully execute this strategy, see: Mazzega M, Fabris F, Cossu S, De Lucchi O, Lucchini V, Valle G. Tetrahedron. 1999;55:4427–4440..

- 6.For examples of related conformational preferences allowing for the atropselective synthesis of a biaryl linkage, see: Meyers AI, Wettlaufer DG. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1984;106:1135–1136. Baker RW, Hambley TW, Turner P, Wallace BJ. Chem. Common. 1996:2571–2572. Koop B, Straub A, Schäfer HJ. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2001;12:341–345. Nishii Y, Wakasugi K, Koga K, Tanabe Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:5358–5359. doi: 10.1021/ja0319442. Hattori T, Date M, Sakurai K, Morohashi N, Kosugi H, Miyano S. Tetrahedron Lett. 2001;42:8035–8038. A similar sp3 to sp2 conversion of an enone was utilized by Baran and coworkers en route to haouamine A, whereby separable macrocyclic enone conformers could be selectively oxidized to form atropdiastereomeric biphenols within the natural product framework, see: Burns NZ, Krylova IN, Hannoush RN, Baran PS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:9172–9173. doi: 10.1021/ja903745s..

- 7.The term “self-immolative” reaction has been used to describe similar processes (see ref. 6a), but we favor the “chirality exchange” term put forth by Nishii and coworkers (ref. 6d) as this is more descriptive in terns of stereochemistry. Adding the term “traceless” reflects our particular interest in such bond disconnections as they apply to synthesis strategy, see: Mundal DA, Avetta CA, Jr, Thomson RJ. Nature Chem. 2010;2:294–297. doi: 10.1038/nchem.576.. For additional discussion into traceless synthetic strategy, see: Steinhardt SE, Vanderwal CD. Natire Chem. 2010;2:254–256. doi: 10.1038/nchem.602. Zhang Y, Danishefsky SJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:9567–9569. doi: 10.1021/ja1035495. Collett N, Carter RG. Nature Chem. 2010;2:613–614. doi: 10.1038/nchem.758..

- 8.For examples, see: Evans DA, Dinsmore CJ, Evrard DA, Devries KM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993;115:6426–6427. Evans DA, Dinsmore CJ, Watson PS, Wood MR, Richardson TI, Trotter BW, Katz JL. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1998;37:2704–2708. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19981016)37:19<2704::AID-ANIE2704>3.0.CO;2-1. Nicolaou KC, Boddy CNC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:10451–10455. doi: 10.1021/ja020736r. Layton ME, Morales CA, Shair MD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:773–775. doi: 10.1021/ja016585u. Clayden J, Mitjans D, Youssef LH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:124–5267. doi: 10.1021/ja017702o. Clayden J, Worrall CP, Moran W, Helliwell M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008;47:3234–3237. doi: 10.1002/anie.200705660. Clayden J, Fletcher SP, McDouall JJW, Rowbottom SJM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:5331–5343. doi: 10.1021/ja900722q. Clayden J, Senior J, Helliwell M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009;48:6270–6273. doi: 10.1002/anie.200901718..

- 9.We have not included more standard chiral auxiliary approaches in this group as conceptually such approaches are different. For examples, see ref. 1.

- 10.Imbos R, Brilman MHG, Pineschi M, Feringa BL. Org. Lett. 1999;1:623–625. [Google Scholar]

- 11.(a) Ito Y, Konoike T, Saegusa T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1975;97:2912–2914. [Google Scholar]; (b) Ito Y, Konoike T, Harada T, Saegusa T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1977;99:1487–1493. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shintani R, Tokunaga N, Doi H, Hayashi T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:6240–6241. doi: 10.1021/ja048825m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rautenstrauch V. Bulletin De La Societe Chimique De France. 1994;131:515–524. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Flack HD. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. A. 1983;39:876–881. [Google Scholar]

- 15.See the Supporting Information for details.

- 16.Walker SD, Barder TE, Martinelli JR, Buchwald SL. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004;43:1871–1876. doi: 10.1002/anie.200353615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bao J, Wulff WD, Rheingold AL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993;115:3814–3815. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.