Abstract

Introduction

Self-injurious behavior (SIB) is common among adolescents, and has been shown to be associated with eating disorders (ED). This study examines the prevalence of SIB and SIB screening in adolescents with ED, and associations with binge eating, purging, and diagnosis.

Methods

Charts of 1,432 adolescents diagnosed with ED, aged 10–21 years, at an academic center between January 1997 and April 2008, were reviewed.

Results

Of patients screened, 40.8% were reported to be engaging in SIB. Patients with a record of SIB were more likely to be female, have bulimia nervosa, or have a history of binge eating, purging, co-morbid mood disorder, substance use, or abuse. Patients who engaged in both binge eating and purging were more likely to report SIB than those engaged in restrictive behavior or either behavior alone. Providers documented screening for SIB in fewer than half of the patients. They were more likely to screen patients who fit a profile of a self-injurer: older patients who binge, purge, or had a history of substance use.

Conclusions

SIB was common in this population, and supports extant literature on associations with bulimia nervosa, mood disorders, binge eating, purging, abuse, and substance use. Providers may selectively screen patients.

Keywords: Adolescent medicine, Self-injury, Eating disorders

Self-injurious behaviors (SIBs) occur in 13%–40% of adolescents, particularly among patients with eating disorders (ED) and borderline personality disorder [1,2]. Although these behaviors are characterized by self-inflicted harm without lethal intent, they nevertheless predict increased mortality from suicide and other causes [2]. SIB is also associated with increased comorbidities including sexual trauma, mood disorders, and substance abuse [1-5]. For accurate prevalence rates of SIB, adequate provider screening is required; however, little is known about SIB screening in adolescents with ED, and most studies reflect selective screening processes without reporting characteristics of those not screened, thus potentially overlooking biases.

Some studies show increased frequencies of SIB in bulimia nervosa (BN) [5,6] and purging subtypes of anorexia nervosa (AN), and suggest that adolescents engaging in multiple ED behaviors are at the highest risk [5,7]. The few studies examining SIB in adolescents associated with ED mirror correlations with sexual abuse [8] and BN [6] in adults. There are no large clinical studies that examine SIB in not only patients with AN and BN, but also in those with eating disorders not otherwise specified.

The present study aimed to retrospectively examine the prevalence of SIB in a large clinical sample of ED adolescents, and to describe associations with binge eating, purging, and diagnostic category. A secondary aim was to report the frequency with which providers screen patients with ED for SIB and the characteristics of patients more likely to be screened. We hypothesized that SIB might be common among ED adolescents screened, and that SIB might be more frequently found among patients diagnosed with BN or those engaged in binge eating and purging behaviors. We also hypothesized that SIB might be infrequently asked about and documented, and that providers would be more likely to screen for SIB in patients fitting a stereotypical profile of a self-injurer.

Methods

Intake evaluations of 1,432 patients aged 10–21 years (135 M, 1,297 F) diagnosed with an ED at an academic ED program between January 1997 and April 2008 were retrospectively reviewed. Data were extracted from evaluations conducted by physicians, mental health practitioners, and dieticians; ED diagnosis was determined after clinical interview with a child psychiatrist or psychologist with expertise in children with EDs, using strict application of criteria from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition. The primary predictor variable was documented as nonlethal self-injury (SIB; e.g., cutting, burning, etc.), and categorized dichotomously. Primary outcomes were ED diagnosis, binge eating, and purging behaviors. Secondary outcomes included histories of laxative use, substance use, or abuse (e.g., sexual, physical, rape, emotional, verbal, bullying, neglect). Protocols were approved by the Stanford University Panel on Medical Research in Human Subjects and were compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) of 1996; a waiver of informed consent and a HIPAA-compliant waiver of individual authorization were granted. Descriptive statistics, chi-squared, Mann–Whitney U, and Kruskal–Wallis tests were performed.

Results

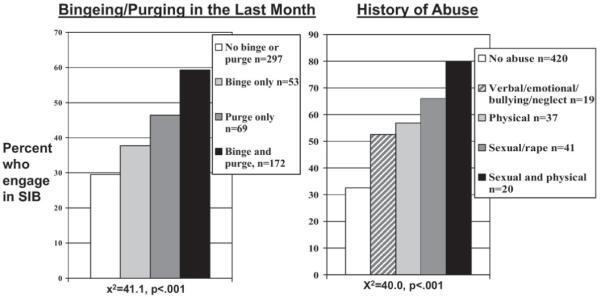

Table 1 presents analyses, showing findings on SIB documentation in the clinical record (42.7% of patients, n = 612), and then findings related to SIB (40.8%, n = 250) in the subset of patients who were screened. Cutting was the most common SIB reported (85.2%, n = 213). Binge eating and purging in the past month and in a lifetime (none: 21.1%, binge: 26.8%, purge: 52.8%, binge/purge: 58.1%, χ2 = 74.5, p < .001) were associated with SIB in a graded manner, as were histories of abuse (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics, SIB documentation, and SIB

| N | Overall | SIB documentation Mean (SD)/% |

No SIB documentation Mean (SD)/% |

p | SIB (self-injurious behavior) Mean (SD)/% |

No SIB Mean (SD)/% |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 1,432 | 15.4 (1.9) | 15.6 (1.9) | 15.2 (1.9) | <.001 | 16.1 (1.6) | 15.4 (2.0) | <.001 |

| Gender | .06 | .001 | ||||||

| Male | 135 | 9.4 | 7.7 | 10.7 | 3.2 | 10.8 | ||

| Female | 1,297 | 90.6 | 92.3 | 89.3 | 96.8 | 89.2 | ||

| Ethnicity (% Caucasian) | 1,048 | 75.3 | 74.7 | 75.8 | NS | 78.5 | 72.0 | .07 |

| %MBWa | 1,432 | 89.9 (19.3) | 91.4 (17.0) | 88.8 (20.8) | <.001 | 95.0 (18.0) | 89.0 (16.0) | <.001 |

| Anorexia nervosa (AN) | 358 | 75.8 (6.5) | ||||||

| Eating disorders not otherwise specified (EDNOS) |

905 | 92.4 (19.7) | ||||||

| Bulimia nervosa (BN) | 169 | 106.5 (16.3) | ||||||

| Months disease | 1,423 | 15.3 (14.6) | 17.2 (15.4) | 13.9 (13.8) | <.001 | 21.7 (17.5) | 14.1 (13.0) | <.001 |

| Purging | ||||||||

| Last month | 452 | 31.6 | 40.0 | 25.5 | <.001 | 54.8 | 29.8 | <.001 |

| Lifetime | 603 | 42.3 | 53.9 | 33.5 | <.001 | 75.4 | 39.2 | <.001 |

| Months purging | 573 | 13.6 (14.5) | 14.5 (15.3) | 12.5 (13.6) | NS | 16.6 (15.9) | 11.7 (14.0) | .001 |

| Binge eating | ||||||||

| Last month | 411 | 30.6 | 37.9 | 24.8 | <.001 | 50.2 | 29.4 | <.001 |

| Lifetime | 503 | 37.4 | 46.4 | 30.4 | <.001 | 60.5 | 36.6 | <.001 |

| Laxative abuse | 254 | 17.7 | 20.9 | 15.4 | .007 | 32.0 | 13.3 | <.001 |

| Diet pill use | 308 | 21.5 | 19.3 | 23.2 | .08 | 31.2 | 11.0 | <.001 |

| Cigarette use | 311 | 21.7 | 24.3 | 19.8 | .04 | 39.2 | 14.1 | <.001 |

| Alcohol use | 582 | 40.6 | 48.9 | 34.5 | <.001 | 67.2 | 36.2 | <.001 |

| Marijuana use | 322 | 22.5 | 28.8 | 17.8 | <.001 | 41.6 | 19.9 | <.001 |

| Other drug use | 147 | 10.3 | 12.4 | 8.7 | .02 | 19.2 | 7.7 | <.001 |

| Comorbid mood disorder | 400 | 27.9 | 33.7 | 23.7 | <.001 | 48.8 | 23.2 | <.001 |

| Antidepressant use | 345 | 24.1 | 26.8 | 22.1 | .04 | 37.2 | 19.6 | <.001 |

| History of abuse | 211 | 17.8 | 21.8 | 14.5 | .001 | 35.1 | 13.2 | <.001 |

| Diagnosis | <.001 | .001 | ||||||

| AN | 358 | 25.0 | 21.2 | 27.8 | 15.6 | 25.1 | ||

| EDNOS | 905 | 63.2 | 63.4 | 63.0 | 63.6 | 63.3 | ||

| BN | 169 | 11.8 | 15.4 | 9.1 | 20.8 | 11.6 | ||

| AN behaviors | ||||||||

| Restrict onlyb | 223 | 67.4 | 54.8 | 74.9 | <.001 | 32.4 | 64.4 | .005 |

| Binge only | 31 | 9.4 | 8.9 | 9.7 | 8.1 | 9.2 | ||

| Purge only | 30 | 9.1 | 11.3 | 7.7 | 16.2 | 9.2 | ||

| Binge/purge | 47 | 14.2 | 25.0 | 7.7 | 43.2 | 17.2 | ||

| Laxative abuse | 44 | 12.3 | 16.9 | 9.6 | .04 | 23.1 | 14.3 | NS |

| Diet pill use | 63 | 17.6 | 14.6 | 19.3 | NS | 25.6 | 9.9 | .02 |

| Cigarette use | 52 | 14.5 | 16.2 | 13.6 | NS | 28.2 | 11.0 | .02 |

| Alcohol use | 105 | 29.3 | 38.5 | 24.1 | .004 | 53.8 | 31.9 | .02 |

| Marijuana use | 59 | 16.5 | 22.3 | 13.2 | .03 | 38.5 | 15.4 | .004 |

| Other drug use | 32 | 8.9 | 13.1 | 6.6 | .04 | 17.9 | 11.0 | NS |

| Comorbid mood disorder | 94 | 26.3 | 29.2 | 24.6 | NS | 46.2 | 22.0 | .005 |

| Antidepressant use | 95 | 26.5 | 28.5 | 25.4 | NS | 38.5 | 24.2 | .1 |

| History of abuse | 38 | 12.9 | 14.0 | 12.2 | NS | 29.4 | 7.5 | .002 |

| EDNOS behaviors | ||||||||

| Restrict onlyb | 424 | 50.4 | 42.7 | 56.5 | <.001 | 23.5 | 55.9 | <.001 |

| Binge only | 80 | 9.5 | 7.7 | 10.9 | 4.6 | 9.9 | ||

| Purge only | 160 | 19.0 | 20.0 | 18.2 | 26.8 | 13.3 | ||

| Binge/purge | 178 | 21.1 | 29.6 | 14.3 | 45.1 | 18.9 | ||

| Laxative abuse | 147 | 16.2 | 17.8 | 15.1 | NS | 29.6 | 9.6 | <.001 |

| Diet pill use | 175 | 19.3 | 16.2 | 21.7 | .04 | 27.0 | 8.7 | <.001 |

| Cigarette use | 182 | 20.1 | 21.6 | 19.0 | NS | 37.1 | 10.9 | <.001 |

| Alcohol use | 357 | 39.4 | 46.4 | 34.2 | <.001 | 66.0 | 32.8 | <.001 |

| Marijuana use | 186 | 20.6 | 24.7 | 17.4 | .007 | 39.0 | 14.8 | <.001 |

| Other drug use | 81 | 9.0 | 10.1 | 8.1 | NS | 17.0 | 5.2 | <.001 |

| Comorbid mood disorder | 245 | 27.1 | 33.8 | 22.1 | <.001 | 47.2 | 24.5 | <.001 |

| Antidepressant use | 196 | 21.7 | 24.5 | 19.5 | .07 | 34.6 | 17.5 | <.001 |

| History of abuse | 130 | 17.3 | 20.6 | 14.5 | .03 | 33.8 | 12.0 | <.001 |

| BN behaviorsc | ||||||||

| Laxative abuse | 63 | 37.3 | 39.4 | 34.7 | NS | 46.2 | 31.0 | NS |

| Diet pill use | 70 | 41.4 | 38.3 | 45.3 | NS | 48.1 | 26.2 | .03 |

| Cigarette use | 77 | 45.6 | 46.8 | 44.0 | NS | 53.8 | 38.1 | NS |

| Alcohol use | 120 | 71.0 | 73.4 | 68.0 | NS | 80.8 | 64.3 | .07 |

| Marijuana use | 77 | 45.6 | 54.3 | 34.7 | .01 | 51.9 | 57.1 | NS |

| Other drug use | 34 | 20.1 | 21.3 | 18.7 | NS | 26.9 | 14.3 | NS |

| Comorbid mood disorder | 61 | 36.1 | 39.4 | 32.0 | NS | 55.8 | 19.0 | <.001 |

| Antidepressant use | 54 | 32.0 | 34.0 | 29.3 | NS | 44.2 | 21.4 | .02 |

| History of abuse | 43 | 30.7 | 38.5 | 21.0 | .03 | 43.9 | 32.4 | NS |

%MBW represents percentage median body weight, where a median weight is determined from the 2000 CDC BMI-for-age percentile growth charts for U.S. boys and girls.

Lifetime histories of restricting only, binge only, purge only, and binge/purge behaviors were analyzed in one 2×4 chi-squared test with regard to SIB documentation and SIB in those whose charts documented this information. As a result, only one p value is reported for these four categories in the corresponding columns.

Lifetime binge and/or purge behaviors were not analyzed separately within the BN category, as all subjects with BN reported both binge eating and purging behaviors.

Figure 1.

Binge and/or purge activity, history of abuse, and self-injurious behavior (SIB).

Discussion

ED adolescents with a record of SIB were more likely to be older or female, have BN or a longer duration of illness, weigh more, or have a history of binge eating, purging, mood disorder, substance use, or abuse. Of patients screened, SIB was reported in 40.8% of adolescents, which was more than the prevalence reported in the literature for the general population, and was consistent with studies of adult patients with ED where rates of 12%–46% [3,4,9] are described, particularly among those who binge eat, purge [5,7], or abuse laxatives [3,5]. Binge and/or purge behaviors were more common in patients reporting SIB even in eating disorders not otherwise specified and AN categories.

As in prior smaller studies [3,4,9], SIB correlated strongly in a graded manner with a history of abuse. In addition, other impulsive behaviors were strongly associated with SIB, supporting studies that reported multi-impulsivity and psychiatric comorbidities in adolescents engaging in SIB [5]. Patients with SIB were more likely to use antidepressants; it is unclear whether these medications might contribute to increased rates of these behaviors because recent literature about suicide risk in antidepressants remains unsettled.

Providers documented screening for SIB in fewer than half of the patients. Screening documentation was more likely in patients meeting a “profile” suggested by the extant adult literature: patients screened were older, had disease for a longer period, and had a history of binge eating, purging, substance use, abuse, or were diagnosed with BN. This could reflect an under-recording in the medical record of negative responses in screening, or that physicians are more likely to screen for self-injury in patients with additional risky behaviors, as has been shown with other behaviors such as drinking [10]. Effective and standardized provider screening is essential given the high rates of SIB among both adolescents and patients with ED who are screened, and the increased risk for suicide in those who self-injure. Further prospective study is warranted to determine the true prevalence in ED adolescents, as these results could be biased by such selective screening.

The study has some limitations including the data that were derived from cross-sectional retrospective chart review. Our data also suggest a possible bias in provider screening and documentation, and we have since added questions about SIB to our structured encounter form used for history-taking, which now helps to cue providers to universally screen for these behaviors. In addition, though statistically significant, some differences such as age may not be clinically significant. Our analyses still reflect a high degree of psychiatric comorbidity and other impulsive behaviors in adolescents with ED who were identified with SIB, and this may indicate a need for more consideration of multi-impulsivity in categorization of ED patients. Identification of these behaviors is clinically important and may mandate a higher degree of urgency in both referral and treatment. There continues to be a need for prospective study of SIB and ED behaviors and more efficient ways to universally screen and triage SIB in these vulnerable populations.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge and thank all the research assistants at the Stanford WEIGHT Laboratory who contributed to data collection and entry. The project was funded in part by the Stanford Child Health Research Program; Jenny Wilson also received funding from the Stanford Medical Scholars Research Program, and Dr. Lock received funding from NIH K24 MH074467.

References

- [1].Bjarehed J, Lundh LG. Deliberate self-harm in 14-year-old adolescents: How frequent is it, and how is it associated with psychopathology, relationship variables, and styles of emotional regulation? Cogn Behav Ther. 2008;37:26–37. doi: 10.1080/16506070701778951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Skegg K. Self-harm. Lancet. 2005;366:1471–83. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67600-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Anderson CB, Carter FA, McIntosh VV, et al. Self-harm and suicide attempts in individuals with bulimia nervosa. Eat Disord. 2002;10:227–43. doi: 10.1002/erv.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Paul T, Schroeter K, Dahme B, et al. Self-injurious behavior in women with eating disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:408–11. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.3.408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Stein D, Lilenfeld LR, Wildman PC, et al. Attempted suicide and self-injury in patients diagnosed with eating disorders. Compr Psychiatry. 2004;45:447–51. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2004.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Ruuska J, Kaltiala-Heino R, Rantanen P, et al. Psychopathological distress predicts suicidal ideation and self-harm in adolescent eating disorder out-patients. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2005;14:276–81. doi: 10.1007/s00787-005-0473-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Favaro A, Santonastaso P. Purging behaviors, suicide attempts, and psychiatric symptoms in 398 eating disordered subjects. Int J Eat Disord. 1996;20:99–103. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-108X(199607)20:1<99::AID-EAT11>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Damsted P, Petersen DJ, Bilenberg N, et al. Suicidal behaviour in a clinical population of 12- to 17-year-old patients with eating disorders. Ugeskr Laeger. 2006;168:3797–801. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Truglia E, Mannucci E, Lassi S, et al. Aggressiveness, anger and eating disorders: A review. Psychopathology. 2006;39:55–68. doi: 10.1159/000090594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].D’Amico EJ, Paddock SM, Burnam A, et al. Identification of and guidance for problem drinking by general medical providers: Results from a national survey. Med Care. 2005;43:229–36. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200503000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]