Abstract

The aim of this study was to determine the impact of sex on the pharmacokinetics of lopinavir/ritonavir. Interaction between lopinavir/ritonavir and tenofovir was also evaluated. Steady-state plasma samples were obtained from virologically suppressed HIV-infected patients on lopinavir/ritonavir 800/200-mg soft gel capsule taken once daily. Drug assays were performed by high-performance liquid chromatography. Pharmacokinetic parameters estimated by noncompartmental method were reported as 90% confidence intervals (CIs) about the geometric mean ratio (GMR). There were 9 males and 11 females. No sex differences were observed in lopinavir/ritonavir pharmacokinetics profile. The GMRsex (women compared with men) for lopinavir area under the concentration–time curve (AUC24), maximum concentration (Cmax), and minimum concentration (Cmin) was 0.95 (90% CI, 0.70–1.29), 0.88 (90% CI, 0.67–1.15), and 1.27 (90% CI, 0.60–2.66), respectively. Similarly, the GMRsex for ritonavir AUC24, Cmax, and Cmin was 0.84 (90% CI, 0.57–1.24), 0.79 (90% CI, 0.50–1.22), and 1.02 (90% CI, 0.58–1.80), respectively. Tenofovir coadministration led to a reduction in lopinavir/ritonavir plasma exposure, giving a lopinavir GMRtenofovir for Cmax of 0.72 (90% CI, 0.57–0.93) and AUC24 of 0.74 (90% CI, 0.56–0.98), respectively. No difference in lopinavir/ritonavir plasma concentrations between sexes was demonstrated in this study. However, tenofovir coadministration lowered lopinavir/ritonavir plasma exposure.

Keywords: Gender- or sex-related differences, lopinavir pharmacokinetics

Observation in antiretroviral (ARV) clinical pharmacology suggests that the same dose of an ARV drug produces varying plasma concentrations in different individuals attributable to interindividual differences in drug processing. This phenomenon of interindividual pharmacokinetic (PK) variability appears to occur across all classes of ARV drugs currently licensed for clinical use. Factors such as sex, race, age, body mass index, genetics, and the concomitant use of certain drugs have been reported to influence plasma drug concentrations.1–5

The plasma concentrations of saquinavir (SQV) when boosted with ritonavir (RTV), for example, have been shown to be significantly higher in women than in men.6,7 Similarly, sex-related differences in plasma concentrations have been observed for nevirapine and efavirenz.8,9 The intracellular triphosphate concentrations of zidovudine and lamivudine were recently reported to be different for men and women.10

Because optimal virologic response often depends on achieving a threshold level of ARV exposure and drug toxicity is often directly correlated with plasma drug concentrations, the extent to which the PK profile of a given ARV agent varies with the sex of patients could have relevance in clinical HIV management.

The primary objective of this study therefore was to assess the influence of sex on the steady-state PK profile of the fixed-dose combination of lopinavir and ritonavir (LPV/r) soft gel capsule formulation (SGC). The population studied included ARV-treated, virologically suppressed HIV-infected men and women whose LPV/r doses were switched from 400/100 mg twice daily to 800/200 mg once daily (QD) 2 weeks before PK sampling. Secondary objectives included the evaluation of QD LPV/r PK profile in this population and the impact of the concomitant use of tenofovir (TDF) on LPV and RTV PK profile.

METHODS

Study Population and Design

Male and female ARV-treated, virologically suppressed HIV-infected subjects who were at least 18 years of age were eligible for enrollment. Entry criteria included a minimum of 3 months of therapy with an ARV regimen consisting of LPV/r (400/100 mg twice daily [BID]) in combination with at least 2 nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs). All subjects were virologically suppressed (HIV RNA <400 copies/mL), and none had significant medical conditions or laboratory parameter abnormalities. There was no CD4 T-cell restriction. Subjects were excluded if they were currently using any cytochrome P450 inhibitors or inducers other than LPV/r or if they were pregnant or breastfeeding. Sexually active females were required to have a negative pregnancy test result and to use barrier contraception during the study. Subjects were recruited from the Grady Health System Infectious Diseases Clinic in Atlanta, Georgia. All subjects provided written informed consent before undergoing any study procedures. This study was designed according to the ethical guidelines for human studies and was approved by the Emory University Institutional Review Board and Grady Health System Research Oversight Committee.

ARV Therapy

During the first 14 days of enrollment, subjects remained on their original LPV/r-containing ARV regimen. From day 15 to day 30 (+2 days), the LPV/r dosing schedule was changed from 400/100 mg BID to 800/200 mg QD. During the entire study period, ARV adherence was monitored through the use of the AARDEX Medication Event Monitoring System (MEMS), and daily bowel movement diaries were kept by participants.

Pharmacokinetic Design

At day 30 (±2 days), participants were admitted to the General Clinical Research Center and underwent 24-hour blood draws for PK analysis. An observed dose of LPV/r (800/200 mg) and background NRTIs were administered with standard breakfast containing 500 to 682 kcal, with 23% to 25% of calories from fat. Serial blood samplings at 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 12, 16, 20, and 24 hours postdose were performed. Blood samples were kept on ice until processed (within 60 minutes of collection). Plasma was separated by centrifugation at 900g for 10 minutes, transferred to a polypropylene cryovial, and frozen at −70°C until shipment to the Antiviral Pharmacology Laboratory at the University of Alabama at Birmingham for analysis.

Pharmacokinetic Assays

A rapid, sensitive, and specific high-performance liquid chromatographic (HPLC) assay was used for the simultaneous quantification of LPV and RTV in 200 µL of human plasma. Reversed-phase chromatographic separation of the drugs and internal standard was performed on a YMC, C8 analytical column (100 × 4.6 mm, 3 µm) under isocratic conditions. A binary mobile phase is used consisting of 55% 20 mM sodium acetate buffer (pH 4.88) and 45% acetonitrile. The ultraviolet detector set to monitor the 212-nm wavelength provides adequate sensitivity with minimal interference from endogenous matrix components. Sample preparation involves liquid-liquid extraction with 2 mL of tert-butylmethylether at basic pH and reconstitution in 100 µL of mobile phase to concentrate the sample. The calibration curves are linear for all drugs over the range of 25 to 20 000 ng/mL.

A reversed-phase HPLC assay, coupled to mass spectrometer for detection, was developed and validated for the determination of tenofovir (9-[9(R)-2-(phosphonomethoxy)propyl]adenine; PMPA), in human plasma. After addition of internal standard (IS) dideoxycytidine (ddC), a solid phase extraction procedure with Waters Oasis MCX 30-mg (1 cc) solid phase extraction cartridges was used to clean up samples and extract the drug of interest. Chromatographic separation was performed on a Waters Atlantis dC18, 2.0 × 100 mm, 3-µm particle size, analytical column. A precolumn is also used to protect and extend the life of the analytical column. The mobile phase consists of 52.2 mM hydroxylamine/4.9 mM acetic acid buffer and methanol, run isocratically at a ratio of 93:7% (by volume). Detection and quantitation of PMPA and IS are achieved by m/z+ by selected ion monitoring, and the protonated molecular ion [M+H]+ is monitored at m/z 288.2 and 212.2 for PMPA and ddC, respectively. The electrospray ion source is heated at 120°C, and the desolvation temperature is set to 350°C. Nitrogen is used as the desolvation and nebulizer gas and is set at 500 L/h and 50 L/h, respectively. The assay is linear in the range of 1.0 to 750 ng/mL and has a minimum quantifiable limit of 1.0 ng/mL using 200 µL of human plasma. The precision for the low validation standard (6 ng/mL), middle validation standard (60 ng/mL), and high validation standard (600 ng/mL) was within the range of 4.6% to 6.5%, whereas the accuracy ranged from −1.2% to 7.6%.

Pharmacokinetic Analysis

PK parameters for LPV, RTV, and TDF were determined using noncompartmental methods (WinNonlin Pro version 4.01, Pharsight Corp, Mountain View, Calif). The maximum LPV and RTV plasma concentrations (Cmax), corresponding time (Tmax), and concentrations just before the next dose (Cmin) were determined by analyzing the individual plasma concentration–time profiles for male and female subjects. The area under the plasma concentration–time curve from time 0 to 24 hours (AUC24) was calculated using the linear-log trapezoidal rule. Oral clearance (CL/F) was calculated as dose divided by AUC.

Statistical Analysis

PK parameters (AUC24, Cmax, Tmax, Cmin, CL/F) were descriptively summarized with percentiles (25th, 50th, and 75th). Statistical analyses by group (gender or TDF use) of the PK parameters were performed on a logarithmic scale so that the data distribution would be roughly Gaussian. Exponentiation of the difference between group means of the log-transformed values provides the geometric mean ratio (GMR). To assess the significance of group differences in the PK parameters for the LPV and RTV, 90% confidence intervals (CIs) were constructed for the GMR. Significant group PK differences were found if the 90% CI for the GMR did not contain 1. Repeated-measures analyses for log LPV and RTV concentrations were analyzed with a means model with SAS Proc Mixed (version 9.1, SAS Institute, Cary, NC) providing separate estimates of the means by time on study and group (gender or TDF use). An unstructured variance-covariance form among the repeated measurements was assumed for each outcome, and robust estimates of the standard errors of parameters were used to perform statistical tests. The model-based means are unbiased with unbalanced data. Statistical tests were 2-sided and performed at a level of significance of .10.

RESULTS

Patient Demographics

Of the 23 subjects enrolled, 20 completed the study including the PK sampling. Three subjects (2 males and 1 female) dropped out. Two subjects were unavailable for the 24-hour PK sampling because of changes in their work schedules, and the third subject was lost to follow-up after the initial study visit. Table I describes the characteristics for the 20 subjects who completed the study. Subjects were mostly African American (70%) with an almost equal number of women (n = 11) and men (n = 9). The median age was higher for males, and the median weight and CD4 T-cell counts were higher for females. Similar proportions of male and female subjects were treated with TDF as part of their ARV regimens. All 20 subjects were virologically suppressed (HIV RNA PCR <400 copies/mL) and had complete adherence to LPV/r during the 30-day study period as measured by the MEMS.

Table I.

Baseline Characteristics of the 20 Subjects for Whom Complete Data Were Available

| Characteristics | N (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 9 (45) |

| Female | 11 (55) | |

| Race | Black, non-Hispanic | 14 (70) |

| White (Hispanic/non-Hispanic) | 6 (30) | |

| Age, y (25%, 75%) | Median age for males | 41.00 (37, 41) |

| Median age for females | 37.00 (33, 47) | |

| Weight, kg (25%, 75%) | Median weight for males | 81.00 (71.20, 81.30) |

| Median weight for females | 85.90 (61, 92.20) | |

| CD4 T-cells/mL (25%, 75%) | Median for males | 306.00 (285, 421) |

| Median for females | 427.00 (342, 812) | |

| Tenofovir use | No | 9 (45) |

| Yes | 11 (55) |

Impact of Sex on LPV and RTV PK Profile

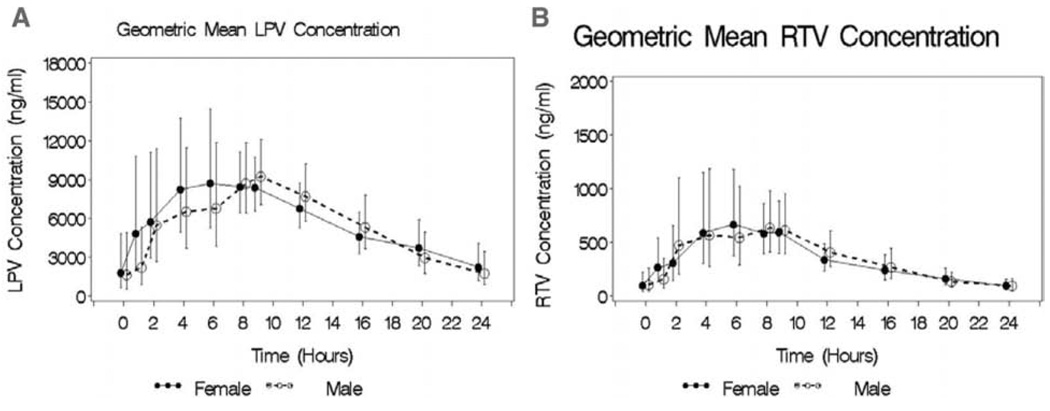

None of the PK parameters assessed for LPV was found to be significantly different for women than for men (Table II). Although a 5% lower LPV AUC24 (GMRsex, 0.95; 90% CI, 0.70–1.29) was observed in men compared with women, this difference was not statistically significant. Similarly, there were nonstatistically significant 12% (GMRsex, 0.88; 90% CI, 0.67–1.15) and 27% (GMRsex, 1.27; 90% CI, 0.60–2.66) sex-related differences in LPV Cmax and Cmin, respectively. Sex-related differences observed in RTV PK parameters were 16% (GMRsex, 0.84; 90% CI, 0.57–1.24) lower AUC24 and 11% (GMRsex, 0.79; 90% CI, 0.50–1.22) lower Cmax in men compared with women; however, these differences were not statistically significant (Table II). RTV Cmin was similar in both sexes (GMRsex, 1.02; 90% CI, 0.58–1.80). Figure 1, which shows graphically how the geometric means for LPV and RTV concentrations of men and women changed during the 24-hour dosing interval, further suggests a lack of gender difference in the LPV/r response at all time points. Because the number of subjects treated with TDF in this cohort was small (n = 11; 5 females and 4 males), the impact of sex on TDF PK could not be adequately assessed. PK parameters for TDF for the cohort are shown in Table II.

Table II.

Pharmacokinetic Parameters for Lopinavir and Ritonavir by Gender and Tenofovir Use

| Drug | Group | AUC24, ng·h/mL | Cmax, ng/mL | Tmax, ha | Cmin, ng/mL | CL/F, L/h |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lopinavir | Cohort median (n = 20) (25%, 75%) | 147 500 (114 500, 202 785) | 12 341 (8205, 13 995) | 4.00 (4.00, 8.00) | 2096 (1107, 4166) | 4.57 (3.03, 5.61) |

| Men median (n = 9) (25%, 75%) | 142 160 (136 300, 191 390) | 12 417 (11 622, 13 699) | 4.00 (4.00, 10.00) | 1395 (1030, 4534) | 4.37 (3.03, 5.46) | |

| Women median (n = 11) (25%, 75%) | 152 140 (110 840, 214 180) | 12 271 (7219, 14 113) | 4.03 (2.58, 8.00) | 2250 (1691, 3954) | 4.76 (3.02, 5.83) | |

| GMRsexb (90% CI) | 0.95 (0.70, 1.29) | 0.88 (0.67, 1.15) | 1.27 (0.60, 2.66) | 1.11 (0.77, 1.61) | ||

| TDF median (n = 11) (25%, 75%) | 134 570 (104 110, 184 460) | 10 897 (7174, 13 049) | 4.00 (4.00, 8.00) | 2250 (529, 3968) | 5.27 (3.19, 5.83) | |

| No-TDF median (n = 9) (25%, 75%) | 191 390 (142 160, 219 000) | 14 113 (12 375, 14 881) | 4.00 (4.00, 8.00) | 1941 (1169, 4365) | 4.06 (2.89, 5.35) | |

| GMRTDFb (90% CI) | 0.74 (0.56, 0.98)c | 0.72 (0.57, 0.93)c | 0.76 (0.36, 1.59) | 1.25 (0.87, 1.79) | ||

| Ritonavir | Cohort median (n = 20) (25%, 75%) | 10 705 (7025, 14 460) | 1269.3 (841.2, 1452.4) | 4.00 (2.29, 9.00) | 96.7 (67.8, 167.6) | 16.73 (12.04, 26.06) |

| Men median (n = 9) (25%, 75%) | 10 410 (9590, 12 980) | 1311.6 (1031.0, 1423.0) | 4.00 (4.00, 8.00) | 91.5 (39.1, 194.4) | 16.09 (12.08, 20.36) | |

| Women median (n = 11) (25%, 75%) | 11 000 (5910, 15 940) | 1226.9 (563.6, 1481.7) | 4.00 (1.00, 10.00) | 101.9 (74.8, 140.8) | 17.37 (11.80, 29.83) | |

| GMRsexb (90% CI) | 0.84 (0.57, 1.24) | 0.79 (0.50, 1.22) | 0.78 (0.40, 1.51) | 1.02 (0.58, 1.80) | 1.17 (0.79, 1.73) | |

| TDF median (n = 11) (25%, 75%) | 8370 (5910, 12 240) | 965.4 (634.5, 1311.6) | 4.00 (2.00, 10.00) | 101.9 (39.1, 140.8) | 22.01 (15.04, 29.83) | |

| No-TDF median (n = 9) (25%, 75%) | 15 940 (10 270, 16 900) | 1481.7 (1362.6, 2409.8) | 4.00 (4.00, 8.00) | 91.5 (80.9, 194.4) | 12.08 (11.08, 18.44) | |

| GMRTDFb (90% CI) | 0.63 (0.45, 0.89)c | 0.55 (0.38, 0.81)c | 1.10 (0.56, 2.13) | 0.89 (0.51, 1.56) | 1.52 (1.05, 2.17)c | |

| TDF | Cohort median (n = 11) (25%, 75%) | 2500 (1500, 3680) | 328.40 (207.20, 292.50) | 2.00 (1.00, 4.57) | 48.60 (31.0, 110.6) | 90.95 (39, 141.04) |

AUC24, area under the concentration–time curve; Cmax, maximum concentration; Tmax, corresponding time; Cmin, minimum concentration; CL/F, oral clearance; CI, confidence interval; TDF, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate.

Because the Tmax of 1 patient was 0, its logarithm and the geometric mean could not be calculated.

GMRsex is the ratio of the geometric means between men and women. Equivalently, it is the antilogarithm of the difference between the means of the log-transformed values between men and women. Similarly, GMRTDF is the ratio of the geometric means between tenofovir use and no tenofovir.

GMR is significantly different from 1 at α = 0.10.

Figure 1.

Geometric mean + SE lopinavir (LPV, A) and ritonavir (RTV, B) concentration–time profiles for male (open symbols and dotted lines) and female (closed symbols and solid lines) subjects who received LPV/r at 800/200 mg QD.

QD LPV/r PK profile

The once-daily LPV and RTV steady-state PK profiles (AUC24, Cmax, Tmax, Cmin, CL/F) for this cohort (Table II) were comparable to previously reported values for LPV/r 800/200 mg QD.11 The 2 weeks of LPV/r 800/200 mg daily were well tolerated by both sexes; none of the 20 subjects who completed the study discontinued ARV therapy during the study period. Although the sample size is modest for this analysis, the median number of self-reported daily bowel movement was comparable between the BID and the QD dosing schedules (3.00 vs 3.08, P = .44).

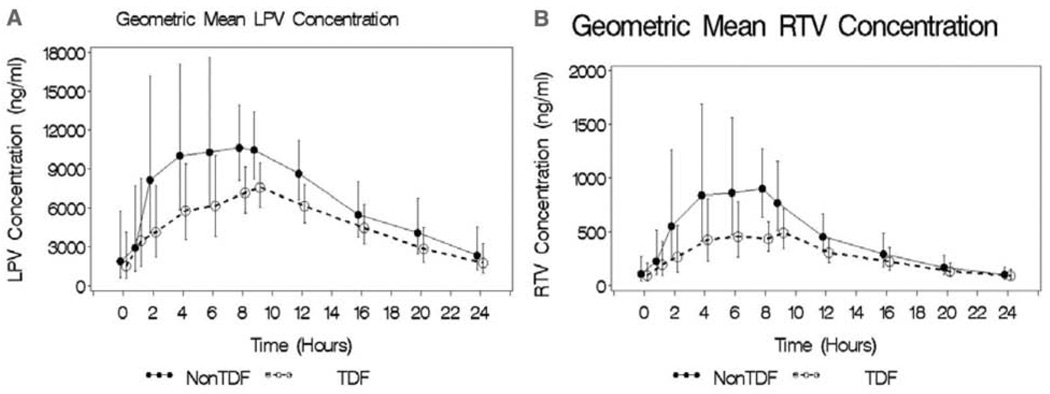

Impact of TDF Coadministration on LPV and RTV PK Profile

In the presence of TDF coadministration, AUC24 and Cmax for LPV significantly decreased, giving a GMRTDF of 0.74 (90% CI, 0.56–0.98) and 0.72 (90% CI, 0.57–0.93), respectively. Moreover, with TDF coadministration, AUC24 and Cmax for RTV were similarly reduced, giving a GMRTDF of 0.63 (90% CI, 0.45–0.89) and 0.55 (90% CI, 0.38–0.81), respectively. Neither the Cmin of LPV (GMRTDF, 0.76; 90% CI, 0.36–1.59) nor that of RTV (GMRTDF, 0.89; 90% CI, 0.51–1.56) was significantly affected by concomitant use of TDF. When mixed model analysis was conducted with TDF as covariate, the interaction of time and log LPV/r concentration was significant, suggesting that in the presence of TDF versus the absence of TDF, subjects exhibited different LPV and RTV concentration profiles at some sampling time points. Figure 2, which shows the LPV and RTV concentrations with TDF and without TDF trajectories, indicates that the difference in mean log LPV and RTV concentrations was most noticeable around 8 hours postdose. The oral clearance of RTV was significantly increased in the presence of TDF (GMRTDF, 1.52; 90% CI, 1.05–2.17). Although the oral clearance of LPV was increased with TDF use (GMRTDF, 1.25; 90% CI, 0.87–1.79), this increase did not reach statistical significance.

Figure 2.

Geometric mean + SE lopinavir (LPV, A) and ritonavir (RTV, B) concentration–time profiles for patients who received LPV/r at 800/200 mg QD plus in the absence (closed symbols and solid lines) or the presence (open symbols and dotted lines) of tenofovir (TDF) at 300 mg daily.

DISCUSSION

Recently, the influence of sex on ARV pharmacology has become a subject of intense clinical investigation. Women were underrepresented in many of the early clinical trials involving ARVs, particularly in the phase I studies. There has been a growing concern that this may have led to an incomplete understanding of the optimal dosing of ARV for female patients.12

Existing data on the influence of sex on the PK profile of LPV consist primarily of abstracts presented in scientific meetings and were generated from retrospective database analyses. In a report by Bertz and colleagues,13 LPV/r PK data obtained from a meta-analysis of 7 single-dose SGC bioavailability studies in healthy adults (144 males, 50 females) were analyzed. Neither LPV Cmax nor AUC was significantly different for women compared with men. Weight had a statistically significant effect on both Cmax and AUC, with a predicted increase of 20% in AUC for a 25% decrease in body weight. In another report, 20 available LPV plasma samples collected as part of routine therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) from 30 subjects (7 women) on LPV/r SGC (400/100 mg BID) regimens were analyzed.14 Only patients whose drug levels were drawn between 10 and 14 hours after LPV dosing were selected for the study. Although the mean LPV concentration in this report was 9% higher in women than in men, this difference was not statistically significant.

In the current report, intensive steady-state PK sampling was obtained prospectively, male and female HIV-infected subjects were equally represented, and information was available to derive and assess PK metrics of interest for LPV, RTV, and TDF. The findings are consistent with those previous reports in that we failed to demonstrate sex-related differences in LPV and RTV PK parameters evaluated. Even after adjustment for subjects’ weight and TDF use, no appreciable differences were observed in either LPV or RTV PK parameters in this cohort. Lack of sex-related differences in the LPV PK profile observed in this and the 2 other reports is reassuring and affirms the current practice of using the same LPV/r dosing schedule for male and female HIV-infected subjects. In addition, the lack of sex-related differences in the LPV/r PK profile in our study is consistent with the reported LPV/r pharmacodynamics for HIV-infected men and women. In a comparison study of LPV/r pharmacodynamics, Cernohous et al15 noted a similar virologic response, as indicated by the proportions of LPV/r-treated female and male patients with HIV RNA <50 copies/mL at week 60 (82% in each group). Immunologic response, as measured by the mean change from baseline to week 60 in CD4 T-cell count, was similar between female (+257 cells/µL) and male (+242 cells/µL) patients receiving LPV/r.15,16

In the only report where sex was observed to affect LPV PK, Burger and colleagues17 analyzed PK data derived from samples in a TDM database. They showed statistically significant higher random concentrations of LPV in females (n = 20) compared with males (n = 110). Females had lower body weights than males, but in a multivariate regression model, only gender was significantly related to increased LPV exposure. Because of the retrospective design of the Burger et al study, only limited PK parameters were available for gender comparison. The influence of meals and other confounders on the PK profile between gender groups could not be ruled out.

Although our study was not powered for this comparison a priori, it was interesting to note that the plasma exposures of both LPV and RTV were reduced by TDF coadministration. The possibility of a potential drug-drug interaction between LPV/r and TDF was first reported by Flaherty et al18 in an intensive PK study of 21 healthy volunteers. Those authors observed a 15% reduction in LPV Cmax and AUC12 values that was statistically significant following concomitant administration with TDF. However, trough plasma concentrations did not differ significantly when LPV was given alone or with TDF. In a later study, these findings could not be reproduced among HIV-infected subjects by Kearney et al.19 In a more recent report by Kearny and colleagues,20 the interaction between LPV and TDF was evaluated in a randomized, prospective crossover study design involving 27 healthy volunteers. Although the authors observed higher TDF plasma exposure in this cohort, LPV and RTV PK profiles were unaffected by TDF coadministration. In the current report, our observations corroborate the earlier findings of Flaherty and colleagues in that the concomitant use of TDF resulted in a statistically significant 26% reduction in LPV Cmax and a 28% reduction in LPV AUC24 but had little effect on LPV Cmin. Similarly, RTV Cmax and AUC24 were statistically significantly reduced by 37% and 45%, respectively, among subjects cotreated with TDF, whereas the Cmin was only slightly affected by TDF coadministration. A statistically significant 52% increase in RTV oral clearance was also noted. This observation is not unique to LPV/r because TDF has also been shown to reduce the plasma exposure of atazanavir.21 Adefovir, a compound closely related to TDF, is known to reduce SQV plasma concentrations by 50% in HIV-infected patients.22 In the setting of treatment-naïve, HIV-infected patients with wild-type virus, a 28% reduction in LPV/r plasma drug exposure is unlikely to have a significant impact on therapeutic outcomes. RTV boosting of LPV via cytochrome P450 3A4 inhibition results in the plasma LPV concentrations that are 50- to 100- fold greater than the EC50 (concentration required to produce 50% of the maximum effect) for wild-type HIV, corrected for plasma protein binding.23 It is therefore reassuring that the safety and efficacy of TDF plus LPV/r in achieving sustained virologic suppression have been demonstrated in a number of long-term clinical trials conducted in both naïve and treatment-experienced patients.24–27

Because tenofovir is excreted unchanged in the urine and is not known to influence the activities of the cytochrome P450 enzyme system, an interaction between TDF and LPV/r at the hepatic biotransformation level is unlikely. However, the absorption of TDF has been shown to involve P-glycoprotein, an important component of the xenobiotic cascade that influences the bioavailability of drugs.28 Because most protease inhibitors (PIs), including LPV/r, are P-glycoprotein substrates, it is conceivable that modulation of the activities of this transporter by TDF could underlie the interaction between the PIs and this drug; however, such speculation will need to be verified.

CONCLUSION

Considering the modest sample size of the cohort in our study, the lack of sex-related differences in LPV/r PK profile observed is in keeping with previous reports. It is also consistent with the finding of equal pharmacodynamic activity (antiviral and immune restoration effects) of LPV/r among HIV-infected men and women in a previous report16 and therefore supports the current practice of uniform LPV/r dosage regardless of gender. The PK profile observed in this cohort suggests the possibility of LPV/r dosing simplification from BID to QD, particularly in a treatmentnaïve setting. A statistically significant reduction in LPV/r Cmax and AUC24 but not Cmin was observed when LPV/r was coadministered with TDF. However, this reduction is not believed to be clinically relevant based on the efficacy of LPV/r plus TDF-containing regimens in long-term controlled clinical trials in HIV-infected subjects.

Acknowledgments

We thank the patients who contributed to the study. We also acknowledge the contribution of the Grady IDP staff and the nurses and technicians at the Grady satellite of the Emory General Clinical Research Center.

Financial disclosure: This work was supported by the following: (1) an independent research grant from Abbott Laboratories, (2) Emory University General Clinical Research Center (NIH grant M01 RR00039), (3) Emory University Center for AIDS Research, Clinical Research and Bio-statistical cores (NIH grant P30 AI050409), and (4) AIDS Clinical Trials Group Minority Fellowship Training Award (NIH grant U01 A138858).

Footnotes

REFERENCES

- 1.Fletcher CV, Acosta EP, Strykowski JM. Gender differences in human pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. J Adolesc Health. 1994;15:619–629. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(94)90628-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Csajka C, Marzolini C, Fattinger K, et al. Population pharmacokinetics of indinavir in patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48:3226–3232. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.9.3226-3232.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hirt D, Urien S, Jullien V, et al. Age-related effects on nelfinavir and M8 pharmacokinetics: a population study with 182 children. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50:910–916. doi: 10.1128/AAC.50.3.910-916.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haas DW, Smeaton LM, Shafer RW, et al. Pharmacogenetics of long-term responses to antiretroviral REGIMENS containing efavirenz and/or nelfinavir: an Adult AIDS Clinical Trials Group Study. J Infect Dis. 2005;192:1931–1942. doi: 10.1086/497610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Department of Health and Human Services. Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-1 infected adults and adolescents. [May 4, 2006];:78–88. Available at: http://aidsinfo.nih.gov/ContentFiles/AdultandAdolescentGL.pdf. [PubMed]

- 6.Fletcher CV, Jiang H, Brundage RC, et al. Sex-based differences in saquinavir pharmacology and virologic response in AIDS Clinical Trials Group Study 359. J Infect Dis. 2004;189:1176–1184. doi: 10.1086/382754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pai MP, Schriever CA, Diaz-Linares M, et al. Sex-related differences in the pharmacokinetics of once-daily saquinavir soft-gelatin capsules boosted with low-dose ritonavir in patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Pharmacotherapy. 2004;24:592–599. doi: 10.1592/phco.24.6.592.34744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhou XJ, Sheiner LB, D’Aquila RT, et al. Population pharmaco-kinetics of nevirapine, zidovudine and didanosine I human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients. The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases AIDS Clinical Trials Group Protocol 241 Investigators. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:121–128. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.1.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burger DM, la Porte CJL, van der Ende, et al. Gender related differences in efavirenz pharmacokinetics. Abstract 3.6. Program and Abstracts of the 4th International Workshop on Clinical Pharmacology of HIV Therapy; March 27–29, 2003; Cannes, France. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anderson PL, Kakuda TN, Kawle S, Fletcher CV. Antiviral dynamics and sex differences of zidovudine and lamivudine triphosphate concentrations in HIV-infected individuals. AIDS. 2003;17:2159–2168. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200310170-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eron JJ, Feinberg J, Kessler HA, et al. Once-daily versus twice-daily lopinavir/ritonavir in antiretroviral-naive HIV-positive patients: a 48-week randomized clinical trial. J Infect Dis. 2004;189:265–272. doi: 10.1086/380799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gleiter CH, Gundert-Remy U. Gender differences in pharmacokinetics. Eur J Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 1996;21:123–128. doi: 10.1007/BF03190260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bertz R, Lam W, Hsu A, et al. Effects of gender, race, age and weight on the pharmacokinetics of lopinavir after single-dose Kaletra™. Abstract 3.11. Program and Abstracts of the 2nd International Workshop on Clinical Pharmacology of HIV Therapy; April 2–4, 2001; Noordwijk, the Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Poirier J, Zouai O, Meynard J, et al. Lack of effect of gender, age, weight and body mass index on trough lopinavir plasma concentrations in HIV-infected patients. Abstract 49. Program and Abstracts of the 4th International Workshop on Clinical Pharmacology of HIV Therapy; March 27–29, 2003; Cannes, France. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cernohous P, Bernstein B, Moseley J, et al. Safety and efficacy of lopinavir/ritonavir in women in a phase iii study of antiretroviral-naïve subjects. Abstract WePeB5972. Program and Abstracts of the XIV International AIDS Conference; July 7–12, 2002; Barcelona, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Walmsley S, Bernstein B, King M, et al. Lopinavir-ritonavir versus nelfinavir for the initial treatment of HIV infection. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:2039–2046. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burger DM, Muller RJ, van de Leur MR, la Porte CJL. Lopinavir plasma levels are significantly higher in females. Abstract 6.5. Program and Abstracts of the 3rd International Workshop on Clinical Pharmacology of HIV Therapy; April 11–13, 2002; Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Flaherty JF, Kearney BP, Wolf JJ, et al. A multiple-dose, randomized, crossover drug interaction study between tenofovir DF and efavirenz, indinavir, or lopinavir/ritonavir. Abstract 336. Program and Abstracts of the 1st IAS Conference on HIV Pathogenesis and Treatment; July 8–11, 2001; Buenos Aires, Argentina. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kearney BP, Mittan A, Sayre J, et al. Pharmacokinetic drug interaction and long term safety profile of tenofovir DF and lopinavir/ritonavir. Abstract A-1617. Program and Abstracts of the 43rd Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy; September 14–17, 2003; Chicago, Ill. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kearney B, Mathias A, Mittan A, et al. Pharmacokinetics and safety of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate on coadministration with lopinavir/ritonavir. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;43:278–283. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000243103.03265.2b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taburet A, Piketty C, Chazallon C, et al. Interactions between atazanavir-ritonavir and tenofovir in Heavily pretreated human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48:2091–2096. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.6.2091-2096.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fletcher CV, Acosta EP, Cheng H, et al. Competing drug-drug interactions among multidrug antiretroviral regimens used in the treatment of HIV-infected subjects: ACTG 884. AIDS. 2000;14:2495–2501. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200011100-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bertz R, Renz C, Foit C, et al. Steady-state pharmacokinetics of Kaletra (lopinavir/ritonavir 400/100 mg BID) in HIV-infected subjects when taken with food. Abstract 3.1. Proceedings of the Second International Workshop on Clinical Pharmacology of HIV Therapy; April 2–4, 2001; Noordwijk, the Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaletra. Kaletra (US prescribing information) North Chicago, Ill: Abbott Laboratories; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnson MA, Gathe JC, Jr, Podzamczer D, et al. A once-daily lopinavir/ritonavir-based regimen provides noninferior antiviral activity compared with a twice-daily regimen. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;43:153–160. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000242449.67155.1a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chiu Y-L, Foit C, Gathe J, et al. Multiple-dose pharmacokinetics and initial antiviral effect of once daily lopinavir/ritonavir (LPV/r) in combination with tenofovir (TDF) and emtricitabine (FTC) in HIV-infected antiretroviral-naive subjects (study 418). Poster presented at: the Second International AIDS Society Conference on HIV Pathogenesis and Treatment; Paris, France. 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnson M, DeJesus E, Grinsztejn B, et al. Long-term efficacy and durability of atazanavir (ATV) with ritonavir (RTV) or saquinavir (SQV) versus lopinavir/ritonavir (LPV/RTV) in HIV-infected patients with multiple virologic failures: 96-Week results from a randomized, open-label trial, BMS AI424045. Abstract #PL14.4. Paper presented at: the 7th International Congress on Drug Therapy in HIV Infection; November 14–18, 2004; Glasgow, UK. [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Gelder J, Deferme S, Naesens L, et al. Intestinal absorption enhancement of the ester prodrug tenofovir disoproxil fumarate through modulation of the biochemical barrier by defined ester mixtures. Drug Metab Dispos. 2002;30:924–930. doi: 10.1124/dmd.30.8.924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]