Introduction

Asthma and respiratory disease account for increasing childhood morbidity, placing a burden on the health care system and on affected individuals and families. In 2007, approximately 6.7 million children under the age of 18 had asthma[1], with rates increasing to nearly 7 million (9.4%) by 2008[2]. As of 2008, more than 14% of children 0–17 had been diagnosed with asthma [2], with children 0–4 years demonstrating the greatest use of health care services for asthma related illness [1]. Increases in childhood respiratory disease over the past decades have highlighted the need to identify specific factors associated with early childhood wheezing and childhood asthma. The rise in prevalence of asthma is too rapid to be due to genetic mutations, and air pollution has actually declined in many areas where asthma rates have been increasing.

Recent research has suggested that maternal dietary factors during pregnancy may influence the development of childhood asthma[3, 4]. The intrauterine environment provides the substrate for many important processes including lung and early immune system development, and support of optimal fetal growth requires adequate maternal nutritional status. Lung development in-utero is apparent within 3–4 weeks after fertilization and continues throughout gestation and childhood[5].[6] It is possible, then, that inadequate nutritional status during gestation may negatively impact childhood respiratory health[3, 4], particularly during critical periods of embryonic and fetal growth.

Maternal anemia, an indicator of overall nutritional status, has been linked to a number of adverse outcomes including infant mortality, preterm delivery, poor gestational weight gain, low birth weight, and poor infant neurocognitive performance[7–9]. Anemia is prevalent in the 4 pregnant population in the United States (9.3% in the general pregnant population and up to 27% in low income minority women[7, 8, 10]}); up to 95% of anemia in pregnancy is attributable to iron deficiency[11] resulting from inadequate iron intake and/or hemodilution of pregnancy.

Given the relatively high prevalence of maternal anemia in pregnancy, and its potential for influencing the respiratory health of offspring through fetal programming effects, further investigation into the role of maternal anemia on childhood respiratory outcomes is warranted. The current study examines the relationship of maternal anemia in pregnancy with patterns of wheezing and asthma in early childhood.

METHODS

Study population

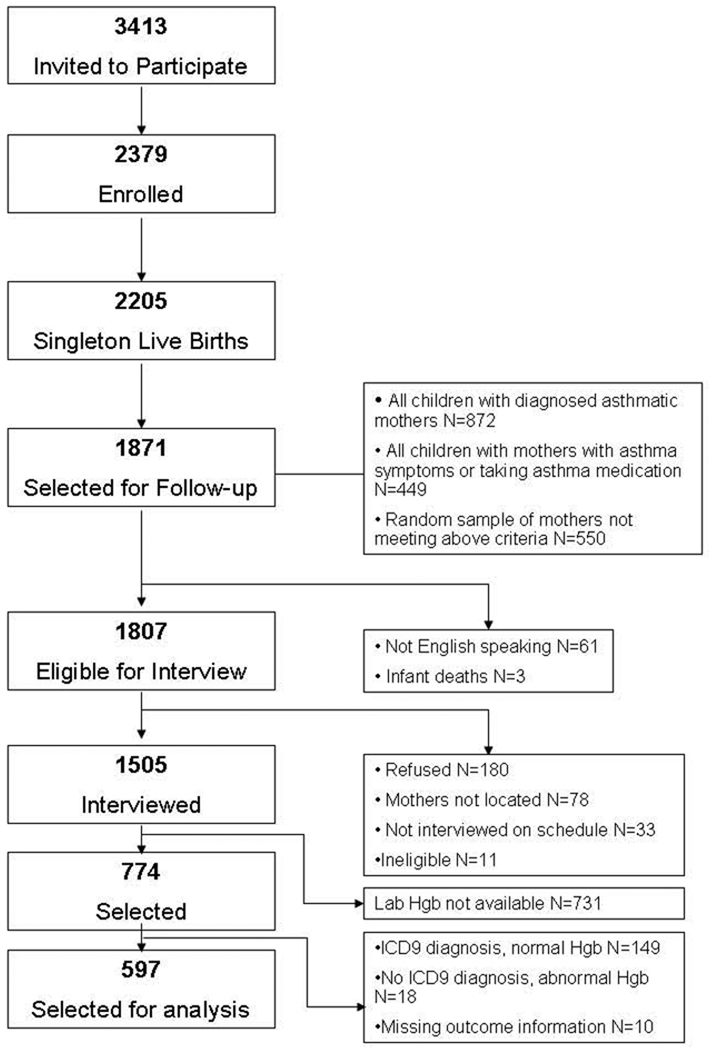

The study population consists of families who participated in the Asthma in Pregnancy (AIP) Study and the Perinatal Risk of Asthma in Infants of Asthmatic Mothers (PRAM) Study. Methods have been described in detail previously[12, 13] (see Figure 1 and eMethods) The current analysis was restricted to 597 families with information available on childhood wheeze patterns, asthma diagnosis, maternal Hgb measurements and ICD9 diagnosis of maternal anemia.

Figure 1.

AIP/PRAM Study Cohort

During the AIP study, pregnant women were interviewed in-person, usually at home, before 24 weeks gestation. A standardized interview collected information on demographic factors, pregnancy history, life-style risk factors (e.g., body mass index (BMI), smoking, drug and alcohol use), asthma history, other medical conditions, and household characteristics. A postpartum interview was conducted during the delivery hospitalization or by telephone within one month of delivery to collect detailed information on asthma symptoms, medication use, and environmental exposures during pregnancy. Medical records for the mother and infant were abstracted using a structured form for pregnancy outcome data, including prenatal, labor and delivery information, and information on the infant’s birthweight, gestational age, and placement in a newborn intensive care unit (NICU).

Families were re-contacted (PRAM) when the children were six years of age (±3 months) and a standardized interview was administered in person with the child’s primary caregiver, usually the mother. Information on the child’s asthma history (symptoms, medication use, and diagnosis), early life exposures (e.g., daycare attendance, breastfeeding, number of children in the household, exposure to tobacco smoking, mold, pets, gas stove use) were collected for the period from birth to age six.

Written or oral consent was obtained from each participant per the guidelines of the local human investigations committee (or IRB).

Exposure assessment

Medical records were abstracted for evidence of maternal anemia during pregnancy. To be classified as having anemia, women had to have both: 1) an ICD-9-CM code of 648.2 “Other current conditions in the mother classifiable elsewhere, but complicating pregnancy, childbirth, or the puerperium: Anemia” and 2) maternal hemoglobin (Hgb) <11 at the time of delivery hospitalization. This third trimester Hgb reference range is consistent with national/international guidelines[7, 14].

Childhood wheezing assessment and asthma diagnosis

A structured interview administered by a trained research assistant at a home visit when the child was six years (+/−3 months) of age elicited detailed information from the child’s mother about the child’s wheezing (including frequency) and asthma diagnosis. Wheeze outcomes for the analysis included recurrent wheeze (two or more episodes) in the first year of life and any wheeze by age 3. Information regarding onset, frequency and duration were also used to classify wheeze patterns as persistent (symptoms still present in the previous 12 months at age six) or transient, and early (≤3 years of age) or late onset as previously described by Martinez[15]. Childhood asthma was based on maternal report of physician diagnosis of asthma; asthma outcomes for the current analysis included both asthma diagnosis ever, and current asthma defined as a physician diagnosis of asthma plus wheeze or medication use during the previous 12 month period.

Data analysis

Statistical analyses examined associations between maternal anemia and childhood respiratory outcomes including 1) recurrent wheeze in the first year of life, 2) wheeze by age 3, 3) asthma diagnosis ever, 4) current asthma, and 5) patterns of wheeze in infancy and early childhood. Unadjusted associations between maternal anemia and each of the outcomes were examined using χ2 tests. Separate logistic regression models were run for each of the dichotomous outcomes (recurrent 1st year wheeze, wheeze by age three, asthma diagnosis ever, and current asthma). Multinomial logistic regression models were fit for the polytomous outcome of childhood wheeze pattern (no wheeze, early onset transient, late-onset, and early onset persistent). Additional analyses stratified the cohort by maternal asthma status. Final models were constructed using backward elimination including exposures of interest and potential confounders. Potential confounders included: gender, maternal race/ethnicity, number of children in the household, maternal asthma diagnosis, allergies, education, pre-pregnancy BMI, smoking in pregnancy, folate supplementation in first trimester, NICU placement at birth, preterm delivery (<37 weeks gestation from LMP), intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), number of months breastfed, and environmental exposures in the first and fifth years of life (smoking in household, pets in home, mold in home, gas stove use in home), and daycare attendance (1st year). All potential confounders were retained in the final models. Because of the strong differential genetic risk that maternal asthma status confers for childhood outcomes, we also stratified analyses by maternal asthma diagnosis. PC-SAS version 9.1 software was used for statistical analysis.

RESULTS

Table 1 presents population characteristics by maternal anemia status, recurrent wheeze in year 1, and current asthma for the cohort (n=597). Slightly over half of the children were male (53%); and 76% were white, non-Hispanic. Mothers with asthma were, by design, over-selected for the study (44% of the cohort had asthma) and an even greater frequency reported maternal allergies (67%). Frequencies of NICU placement at birth (18%), preterm delivery (9%) and intrauterine growth restriction (7%) were typical for this population. During the first year of life, 5% reported smoking in the household, 33% of infants were in daycare, 56% had pets in the home and 15% reported mold in the home.

Table 1.

Associations Between Population Characteristics, Maternal Anemia, Childhood Wheeze and Asthma Diagnosis

| Childhood Respiratory Outcomes | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total N1 |

% with maternal anemia in pregnancy |

P-value | % Recurrent wheeze year 1 |

P-value | % active asthma at age 6 |

P-value | |

| Overall | 597 | 11.9 | 22.1 | 17.2 | |||

| Child gender | 0.55 | 0.38 | 0.03 | ||||

| Male | 314 | 11.2 | 23.5 | 20.4 | |||

| Female | 283 | 12.7 | 20.5 | 13.8 | |||

| Child's race/ethnicity | <0.0001 | <0.001 | <0.0001 | ||||

| White | 452 | 8.0 | 18.5 | 13.1 | |||

| African-American | 43 | 30.2 | 38.1 | 25.6 | |||

| Hispanic | 47 | 29.8 | 39.1 | 42.6 | |||

| Biracial | 54 | 14.8 | 22.6 | 24.1 | |||

| # of children in household | 0.08 | 0.56 | 0.04 | ||||

| 1 child | 91 | 12.1 | 19.1 | 26.4 | |||

| 2 children | 296 | 9.1 | 23.9 | 16.2 | |||

| 3 or more children | 210 | 15.7 | 20.9 | 14.8 | |||

| Maternal asthma | 0.08 | <0.001 | <0.0001 | ||||

| No | 336 | 9.8 | 17.0 | 11.9 | |||

| Yes | 261 | 14.6 | 28.6 | 24.1 | |||

| Maternal allergies | 0.39 | 0.55 | 0.007 | ||||

| No | 195 | 10.3 | 23.6 | 11.3 | |||

| Yes | 402 | 12.7 | 21.4 | 20.2 | |||

| Maternal education | 0.01 | 0.009 | 0.0007 | ||||

| < high school | 50 | 24.0 | 39.6 | 30.0 | |||

| High school graduate | 80 | 15.0 | 26.6 | 16.2 | |||

| Some college | 151 | 16.6 | 21.8 | 22.5 | |||

| College graduate | 155 | 6.5 | 21.9 | 18.7 | |||

| > college | 159 | 7.6 | 15.3 | 7.5 | |||

| Maternal pre-pregnancy body mass index (BMI) | 0.56 | 0.03 | 0.38 | ||||

| Underweight | 61 | 14.8 | 18.3 | 21.3 | |||

| Normal weight | 326 | 10.4 | 18.4 | 15.0 | |||

| Overweight | 64 | 15.6 | 33.9 | 15.6 | |||

| Obese | 141 | 12.8 | 25.5 | 20.6 | |||

| Maternal smoking in 1st trimester of pregnancy | 0.008 | 0.06 | 0.13 | ||||

| No | 515 | 10.5 | 20.8 | 16.3 | |||

| Yes | 82 | 20.7 | 30.4 | 23.2 | |||

| Folate supplementation | <0.0001 | 0.002 | 0.01 | ||||

| <270 | 119 | 26.1 | 33.6 | 26.1 | |||

| 270 to <500 | 121 | 10.7 | 25.2 | 19.0 | |||

| 500 to <700 | 155 | 9.7 | 18.8 | 14.2 | |||

| 700 or higher | 197 | 6.1 | 15.8 | 12.7 | |||

| NICU placement | 0.14 | 0.001 | 0.01 | ||||

| No | 492 | 12.8 | 19.5 | 15.4 | |||

| Yes | 105 | 7.6 | 34.0 | 25.7 | |||

| Preterm delivery | 0.93 | 0.003 | 0.12 | ||||

| No | 545 | 11.9 | 20.5 | 16.5 | |||

| Yes | 52 | 11.5 | 38.5 | 25.0 | |||

| Small for gestational age (SGA) | 0.71 | 0.10 | 0.85 | ||||

| No | 552 | 11.8 | 21.1 | 17.0 | |||

| Yes | 44 | 13.6 | 31.8 | 18.2 | |||

| Breastfeeding (# months) | 0.02 | 0.001 | 0.23 | ||||

| None | 183 | 18.6 | 28.9 | 20.2 | |||

| 1 – 3 | 107 | 9.4 | 20.9 | 20.6 | |||

| 4 – 6 | 92 | 8.7 | 30.0 | 18.5 | |||

| 7 – 12 | 125 | 8.8 | 16.0 | 13.6 | |||

| >12 | 90 | 8.9 | 10.0 | 11.1 | |||

| Household smoking – yr 1 | 0.19 | 0.34 | 0.75 | ||||

| No | 566 | 11.5 | 21.7 | 17.1 | |||

| Yes | 31 | 19.4 | 29.0 | 19.4 | |||

| Household smoking – yr 5 | 0.28 | 0.53 | 0.32 | ||||

| No | 563 | 11.5 | 21.8 | 16.9 | |||

| Yes | 34 | 17.6 | 26.5 | 23.5 | |||

| Day care – yr 1 | 0.63 | 0.002 | 0.88 | ||||

| No | 400 | 11.5 | 18.4 | 17.5 | |||

| Yes | 194 | 12.9 | 29.5 | 17.0 | |||

| Pets in home – yr 1 | <0.0001 | 0.45 | 0.01 | ||||

| No | 264 | 17.8 | 23.5 | 21.6 | |||

| Yes | 333 | 7.2 | 20.9 | 13.8 | |||

| Pets in home – yr 5 | <0.0001 | 0.54 | 0.01 | ||||

| No | 225 | 18.7 | 23.4 | 22.2 | |||

| Yes | 372 | 7.8 | 21.3 | 14.2 | |||

| Mold in home - year 1 | 0.65 | 0.74 | 0.66 | ||||

| No | 506 | 11.7 | 21.9 | 17.0 | |||

| Yes | 90 | 13.3 | 23.5 | 18.9 | |||

| Mold in home – yr 5 | 0.82 | 0.03 | 0.34 | ||||

| No | 473 | 12.1 | 20.1 | 16.5 | |||

| Yes | 124 | 11.3 | 29.5 | 20.2 | |||

Ns may not sum to total due to missing values

Overall, 11.9% of the mothers were identified through medical record abstraction as having maternal anemia in pregnancy. Among their children, 22% had recurrent wheeze in year 1, and 17% had active asthma at age 6 (physician-diagnosed asthma plus wheeze or medication use in the past year). Women with African-American and Hispanic children, with lower education, and with lower folate supplementation during the first trimester of pregnancy were more likely to have anemia in pregnancy; in addition, their children were more likely to have recurrent year 1 wheeze and active asthma at age 6. Maternal smoking in pregnancy, not breastfeeding, and having no pets in the home were also associated with maternal anemia. Recurrent wheeze in the first year of life was more frequent among children of mothers with asthma, higher pre-pregnancy BMI, NICU placement, preterm delivery, shorter duration of breastfeeding, daycare in the first year of life, and mold in the home. Child gender, having only one child in the household, maternal asthma and allergies, NICU placement, and having no pets in the home were associated with active asthma at age 6.

Table 2 presents unadjusted associations between maternal anemia, early childhood wheeze, and asthma outcomes. Women with maternal anemia were more likely to have infants with recurrent wheeze in the first year of life compared to mothers without anemia (OR=2.52, 95% CI 1.50, 4.23); similarly, odds of wheezing before age 3 among children born to mothers with anemia was significantly elevated compared to non-anemic mothers (OR=2.44, 95% CI 1.48, 4.04). Maternal anemia was also associated with their child’s asthma; mothers anemic during pregnancy were more likely to have a child ever diagnosed with asthma (OR=2.37, 95% CI 1.39, 4.03), and a child with asthma at age 6 (OR=2.64, 95% CI 1.54, 4.53) than non-anemic women.

Table 2.

Unadjusted associations between maternal anemia and childhood respiratory outcomes

| Maternal anemia1 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OUTCOME | N | No | Yes | OR | 95% CI |

| Shorter-term outcomes | |||||

| Year 1 recurrent wheeze | |||||

| No | 462 | 417 | 45 | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 131 | 103 | 28 | 2.52 | 1.50, 4.23 |

| Wheeze before age 3 | |||||

| No | 368 | 338 | 30 | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 230 | 189 | 41 | 2.44 | 1.48, 4.04 |

| Longer-term outcomes | |||||

| Asthma diagnosis - ever | |||||

| No | 486 | 437 | 49 | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 119 | 94 | 25 | 2.37 | 1.39, 4.03 |

| Asthma diagnosis + wheeze or med use at age 6 | |||||

| No | 501 | 451 | 50 | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 106 | 82 | 24 | 2.64 | 1.54, 4.53 |

Maternal anemia defined as measured hemoglobin ≤11 at time of delivery hospitalization + indication in medical chart that patient was diagnosed with anemia.

Results of adjusted logistic regression models are presented in Table 3. Maternal anemia remained significantly associated with recurrent wheeze during the 1st year of life (ORa=2.11, 95% CI 1.12, 3.98), as well as wheeze before age 3 (ORa=2.36, 95% CI 1.34, 4.17). After adjustment for confounders, associations between maternal anemia and asthma outcomes were attenuated: odds of asthma diagnosis ever (ORa=1.60, 95% CI 0.83, 3.07) and asthma at age 6 (ORa=1.76, 95% CI 0.90, 3.43) were non-significantly higher among children born to anemic mothers.

Table 3.

Adjusted1 odds ratios of associations between maternal anemia and respiratory health outcomes, all children combined and stratified by maternal asthma status

|

OUTCOME |

All children | Non-asthmatic mothers |

Asthmatic mothers | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ORa | 95% CI | ORa | 95% CI | ORa | 95% CI | |

| Shorter-term outcomes | ||||||

| Year 1 recurrent wheeze | 2.11 | 1.12–3.98 | 1.64 | 0.58–4.61 | 4.78 | 1.75–13.08 |

| Wheeze before age 3 | 2.36 | 1.34–4.17 | 2.58 | 1.10–6.05 | 2.83 | 1.19–6.75 |

| Longer-term outcomes | ||||||

| Asthma diagnosis - ever | 1.60 | 0.83–3.07 | 0.77 | 0.21–2.78 | 2.98 | 1.21–7.34 |

| Asthma diagnosis + wheeze or med use at age 6 | 1.76 | 0.90–3.43 | 0.66 | 0.17–2.57 | 3.80 | 1.52–9.53 |

Adjusted for child's gender, race, # children in household at age 6, maternal allergies, maternal education, pre-pregnancy BMI, maternal smoking in 1st trimester, folate supplementation in first trimester, NICU admission, preterm delivery, SGA, # months breastfed, smoking in household in years 1 and 5, daycare attendance in year 1, pets in years 1 and 5, mold in years 1 and 5.

Among asthmatic mothers, maternal anemia remained significantly associated with increased odds of recurrent wheeze in the first year (ORa=4.78, 95% CI 1.75, 13.08), wheeze by age 3 (ORa=2.83, 95% CI 1.19, 6.75), asthma diagnosis ever (ORa=2.98, 95% CI 1.21, 7.34), and current asthma (ORa=3.80, 95% CI 1.52, 9.53). Among non-asthmatic mothers, maternal anemia remained associated with wheeze before age 3 (ORa=2.58, 95% CI 1.10, 6.05).

Among all children, maternal anemia was associated with a nearly three-fold increase in odds of early onset transient wheeze (ORa=2.76, 95%CI 1.35, 5.64) but not late onset wheezing (ORa=0.77, 95% CI 0.22, 2.65) (Table 4). Early onset persistent wheezing in children of mothers with anemia increased two-fold (ORa=1.96, 95% CI 0.95, 4.03). Stratified by maternal asthma status, maternal anemia remained associated with increased odds of early onset transient wheeze for children of non-asthmatic mothers (ORa=3.90, 95% CI 1.43, 10.6), but the association was attenuated among asthmatic mothers (ORa=2.56, 95% CI 0.77, 8.50). There were too few observations to estimate the association for late onset wheezing among offspring of non-asthmatic mothers, and there was no association of anemia in asthmatic mothers with children’s late-onset wheezing (ORa=0.72, 95% CI 0.11, 4.60). The association between anemia and early onset persistent wheeze was more pronounced among asthmatic mothers (ORa=3.67, 95% CI: 1.27, 10.6) than among non-asthmatic mothers (ORa=1.18, 95% CI: 0.35, 4.04).

Table 4.

Adjusted associations between maternal anemia and childhood wheeze patterns, all children combined and by maternal asthma status1

| Wheeze Pattern2 | All children | Non-asthmatic mothers | Asthmatic mothers | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ORa | 95% CI | ORa | 95% CI | ORa | 95% CI | |

| No wheeze | ref | ref | ref | |||

| Early-onset, transient | 2.76 | 1.35–5.64 | 3.90 | 1.43–10.6 | 2.56 | 0.77–8.50 |

| Late-onset | 0.77 | 0.22–2.65 | NAC3 | 0.72 | 0.11–4.60 | |

| Early-onset, persistent | 1.96 | 0.95–4.03 | 1.18 | 0.35–4.04 | 3.67 | 1.27–10.6 |

Adjusted for child's gender, race, # children in household at age 6, maternal allergies, maternal education, pre-pregnancy BMI, maternal smoking in 1st trimester, folate supplementation in first trimester, NICU admission, preterm delivery, SGA, # months breastfed, smoking in household in years 1 and 5, daycare attendance in year 1, pets in years 1 and 5, mold in years 1 and 5.

Early-onset transient wheeze=wheeze onset <3 years but no symptoms by age 6; late-onset wheeze=wheeze ≥3 years; early-onset persistent wheeze=wheeze <3 years and wheeze at age 6

NAC (not able to calculate)

DISCUSSION

Maternal anemia during pregnancy was associated with both short-term (recurrent wheeze in first year of life and wheeze by 3 years of age) and longer-term (asthma diagnosis ever and asthma at age 6) respiratory health outcomes in children. Maternal asthma status appears to modify these associations. Among asthmatic mothers, maternal anemia is associated with an increase in odds of more persistent respiratory outcomes, including asthma and persistent wheeze in the children at age 6. Among non-asthmatic mothers, maternal anemia was more strongly associated with shorter-term respiratory outcomes in the children.

Results reported here for wheeze complement and extend the findings of a previous investigation examining the effect of in-utero iron exposure and early wheeze, where cord iron levels were inversely related to early childhood wheezing, OR=0.86, 95% CI 0.75, 0.99 per doubling of iron concentration[16]. Infants born to mothers with anemia may have normal iron levels because of active placental iron transport; however, levels are typically lower than those in infants born to non-anemic mothers[17–19]. Associations between maternal anemia and early life respiratory outcomes (particularly 1st year of life) may be expected to be strongest because exposures to iron stores from pregnancy typically last only through the first 6 months of life[20, 21]. However, as found in our study, the effects of in-utero exposures could persist longer than the first year of life[22–24]. Our observation that associations between anemia and childhood wheeze differ based on maternal asthma status suggests that programming effects of maternal nutritional status on the child’s respiratory health may be particularly important among children with a genetic predisposition for asthma. Associations of maternal anemia on respiratory outcomes and childhood asthma may be indicative of fetal programming or childhood nutritional status.

A US study found nonhereditary, non-hemolytic anemia to be the most common complication of pregnancy with rates around 9.3%[10], in accord with the prevalence rate in this study. However, among low income minority populations in the United States, iron deficiency anemia is approximately 27% in the third trimester[7, 8]. Even in the United States, where anemia rates are relatively low and severe anemia is quite rare compared to developing countries with rates as high as 73% reported[25], this study was able to document associations with respiratory health.

Objective measure of maternal anemia was a major strength of this study. Comprehensive assessment of maternal anemia at the time of delivery, using both ICD-9 codes and laboratory values of Hgb, significantly reduced the potential for exposure misclassification. However, the underlying cause of the anemia (e.g., inadequate dietary iron intake, dilution due to large increase in plasma volume in pregnancy, impaired absorption) was not ascertained. We utilized Hgb cut-off of <11 to classify maternal anemia which is appropriate for the third trimester of pregnancy, and has been used to define anemia in pregnancy[26–28]; the cutoff of 11, compared to the cutoff of 12 typically used to indicate anemia in non-pregnant women, accounts at least in part for some level of dilution that is normal in pregnancy.

Another strength was the ability to control numerous potentially important confounding variables, including folate supplementation, many of which were assessed prospectively with respect to the respiratory outcomes. These factors could potentially explain the association of maternal anemia on respiratory outcomes, yet the overall conclusions were relatively unchanged following adjustment in logistic regression modeling. The robust sample size (n=597), together with the overrepresentation of asthmatic mothers, allowed for examination of modifying effects by maternal asthma status.

There are some limitations that should be considered. Because of the time elapsed between information ascertainment at age 6 and symptoms in the first year of life, there may be recall error for the short-term respiratory outcomes. The current analysis is based on medical reports of anemia and assumes iron deficiency based on clinical diagnosis. However, medical charts are not expected to be differentially influenced by recall, and non-differential recall would force the risk estimate toward the null. Moreover, the hypothesis of anemia and asthma would not be familiar to physicians, patients or research staff, making ascertainment bias unlikely. Associations between anemia and longer-term outcomes based on current respiratory symptoms are less likely to be affected by inaccurate reporting.

Another potential limitation was the availability of Hgb levels at time of delivery on only a subset of the larger cohort of 1505 women. We considered the possibility that missing Hgb could be related to our study outcomes. However, availability of Hgb in our study was unrelated to subsequent childhood asthma and respiratory symptom outcomes in our study. We chose the more specific rather than sensitive measure of exposure, and only classified women who met both criteria (ICD-9 diagnosis of anemia at some point in pregnancy and Hgb <11 at time of delivery) as having maternal anemia. As a sensitivity analysis, we repeated study analyses redefining maternal anemia as an ICD-9 code noted at any point in the patient’s medical record. While the conclusions were consistent with those using the more specific measure, the associations were attenuated, most likely due to non-differential misclassification. For example, the less specific measure included women who may have been anemic and successfully treated early in pregnancy with less chance of affecting the fetus.

As the literature in this area is limited, specific biological mechanisms to explain the association between maternal anemia and respiratory symptoms are unclear. Maternal anemia is an indicator of general nutritional status, and thus may be a proxy for a specific causal agent. For example, other micronutrients have been identified in the development of infant susceptibility to respiratory disease, including: selenium[16, 29], maternal vitamin D[30], and vitamin C[31], zinc[32, 33], vitamin E[32–34] and folic acid [35, 36]. While we did not have data on specific micronutrient intake, we were able to adjust for folate supplementation during the first trimester of pregnancy. While folate supplementation was associated with maternal anemia, associations between maternal anemia and respiratory outcomes were not substantially changed when folate was included in the models. The association of folic acid supplementation in this study has been analyzed in detail elsewhere and no evidence was found for an association with asthma risk in children aged six.[37]. Folic acid supplementation was not, therefore, a confounding factor in this analysis of maternal anemia.

It is also possible that iron deficiency, the single most common cause of maternal anemia in pregnancy, may directly impact childhood respiratory health. Dietary changes have been substantial during the past few decades[38, 39]. Analysis of NHANES data showed improvements in iron intake during 1971–2000 among males and children; however iron deficient anemia has increased for low income women of childbearing age, and is highest in prevalence among minority females[40]. Iron intake continues to be low for female adolescents, both in the US and Europe, despite increased total energy intake since the 1960’s[41, 42]. Previous research has demonstrated an increased risk between high serum iron and asthma[43–45]; however, these were retrospective investigations of adult or childhood iron levels, rather than in-utero exposures.

Further research is needed to confirm these findings and to understand how maternal anemia may influence childhood respiratory health. Identification of such mechanisms may lead to targeted interventions to reduce the burden of childhood respiratory disease, particularly in those born to women with asthma. Cohort studies investigating iron levels, other nutritional biomarkers, and dietary patterns, from in-utero throughout childhood, will be critical to understanding the long-term effects of nutritional status on risk of respiratory disease.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Financial Support: This work was supported by grant # AI41040

Biographies

Elizabeth Triche conceived of the research idea, was co-Investigator on the grant that collected the original data, analyzed the data, wrote the methods and results, and provided critical feedback and guidance for the introduction/background and the discussion.

Lisbet Lundsberg wrote sections of the introduction and discussion, was involved in substantial revisions of the original manuscript, and provided critical feedback on the methods and results.

Paige Wickner provided critical feedback on all sections of the manuscript, particularly the clinical interpretation of the findings. She was involved in substantial revisions and editing of the manuscript.

Kathleen Belanger was co-Investigator on the grant that collected the original data and critically reviewed the manuscript.

Brian Leaderer was co-Investigator on the grant that collected the original data and critically reviewed the manuscript

Michael Bracken was Principal Investigator on the grant that collected the original data, provided valuable feedback on the analysis and interpretation of results, and critically reviewed the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest: Michael Bracken and Paige Wickner work as occasional contractors for Pfizer although the research in this paper is not related in any way to compensation received from this company. All other authors do not have any conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Elizabeth W. Triche, Brown University, Department of Community Health/Epidemiology, Providence, RI

Lisbet S. Lundsberg, Yale Center for Perinatal, Pediatric and Environmental Epidemiology, Yale University, New Haven, CT

Paige G. Wickner, Section of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, Department of Internal Medicine, Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, CT

Kathleen Belanger, Yale Center for Perinatal, Pediatric and Environmental Epidemiology, Yale University, New Haven, CT

Brian P. Leaderer, Yale Center for Perinatal, Pediatric and Environmental Epidemiology, Yale University, New Haven, CT

Michael B. Bracken, Yale Center for Perinatal, Pediatric and Environmental Epidemiology, Yale University, New Haven, CT

Bibliography

- 1.Akinbami LJ, Moorman JE, Garbe PL, Sondik EJ. Status of childhood asthma in the United States, 1980–2007. Pediatrics. 2009;123 Suppl 3:S131–S145. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2233C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bloom B, Cohen RA, Freeman G. Summary health statistics for U.S. children: National Health Interview Survey, 2007. Vital Health Stat 10. 2009;(239):1–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pali-Scholl I, Renz H, Jensen-Jarolim E. Update on allergies in pregnancy, lactation, and early childhood. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123(5):1012–1021. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.01.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Devereux G. Early life events in asthma - diet. Pediatric Pulmonology. 2007;42:663–673. doi: 10.1002/ppul.20640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burri PH. Structural aspects of prenatal and postnatal development and growth of the lung. In: McDonald JA, editor. Lung Growth and Development. New York: Marcel Dekker, Inc.; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Joshi S, Kotecha S. Lung growth and development. Early Hum Dev. 2007;83(12):789–794. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2007.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.ACOG. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 95: anemia in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(1):201–207. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181809c0d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scholl TO. Iron status during pregnancy: setting the stage for mother and infant. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;81(5):1218S–1222S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/81.5.1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Keen CL, Clegg M, Hanna L, Lanoue L, Rogers J, Daston G, Oteiza P, Uriu-Adams J. The plausibility of micronutrient deficiencies being a significant contributing factor to the occurrence of pregnancy complications. J Nutrition. 2003;133:1597S–1605S. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.5.1597S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bruce FC, Berg CJ, Hornbrook MC, Whitlock EP, Callaghan WM, Bachman DJ, Gold R, Dietz PM. Maternal morbidity rates in a managed care population. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111(5):1089–1095. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31816c441a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Merck Manuals Online. Anemia in Pregnancy. 2008 [cited July 27, 2009; Available from: http://www.merck.com/mmpe/sec18/ch261/ch261b.html.

- 12.Kang EM, Lundsberg LS, Illuzzi JL, Bracken MB. Prenatal exposure to acetaminophen and asthma in children. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114(6):1295–1306. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181c225c0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bracken M, Triche E, Belanger K, Saftlas A, Beckett W, Leaderer B. Asthma symptoms, severity, and drug therapy: a prospective study of effects on 2205 pregnancies. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102(4):739–752. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(03)00621-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization. Iron deficiency anaemia: assessment, prevention and control. 2001

- 15.Martinez F, Wright A, Taussig L, Holberg C, Halonen M, Morgan W Group Health Medical Associates. Asthma and wheezing in the first six years of life. N Eng J Med. 1995;332(3):133–138. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199501193320301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shaheen S, Newson R, Henderson A, Emmett P, Sherriff A, Cooke M ALSPAC Study Team. Umbilical cord trace elements and minerals and risk fo early childhood wheezing and eczema. Eur Respir J. 2004;24:292–297. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00117803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Milman N. Serum ferritin in Danes: studies of iron status from infancy to old age, during blood donation and pregnancy. Int J Hemtol. 1996;63(2):103–135. doi: 10.1016/0925-5710(95)00426-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Allen LH. Anemia and iron deficiency: effects on pregnancy outcome. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;71 Suppl:12880S–12884S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/71.5.1280s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jaime-Perez JC, Herrera-Garza JL, G-A D. Sub-optimal fetal iron acquisition under a maternal environment. Arch Med Res. 2005;36:598–602. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2005.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Siimes MA, Addiego JE, Jr, Dallman PR. Ferritin in serum: diagnosis of iron deficiency and iron overload in infants and children. Blood. 1974;43(4):581–590. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hay G, Refsum H, Whitelaw A, Melbye EL, Haug E, Borch-Iohnsen B. Predictors of serum ferritin and serum soluble transferrin receptor in newborns and their associations with iron status during the first 2 y of life. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;86(1):64–73. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/86.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barker DJ. A new model for the origins of chronic disease. Med Health Care Philos. 2001;4(1):31–35. doi: 10.1023/a:1009934412988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mathers JC. Early nutrition: impact on epigenetics. Forum Nutr. 2007;60:42–48. doi: 10.1159/000107066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Burdge GC, Hanson MA, Slater-Jefferies JL, Lillycrop KA. Epigenetic regulation of transcription: a mechanism for inducing variations in phenotype (fetal programming) by differences in nutrition during early life? Br J Nutr. 2007;97(6):1036–1046. doi: 10.1017/S0007114507682920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pathak P, Kapil U, Kapoor SK, Saxena R, Kumar A, Gupta N, Dwivedi SN, Singh R, Singh P. Prevalence of multiple micronutrient deficiencies amongst pregnant women in a rural area of Haryana. Indian J Pediatr. 2004;71(11):1007–1014. doi: 10.1007/BF02828117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kumar ARA, Basu S, Dash D, Singh JS. Cord blood and breast milk iron status in maternal anemia. Pediatrics. 2008;121(3):673–677. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brion MJ, Leary SD, Smith GD, McArdle HJ, Ness AR. Maternal anemia, iron intake in pregnancy, and offspring blood pressure in the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;88(4):1126–1133. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/88.4.1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kilbride J, Baker TG, Parapia LA, Khoury SA, Shuqaidef SW, J D. Anaemia during pregnancy as a risk factor for iron-deficiency anaemia in infancy: a case-control study in Jordan. International Journal of Epidemiology. 1999;28(3):461–468. doi: 10.1093/ije/28.3.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Devereux G, McNeill G, Turner S, Craig L, Martindale S, Helms P, S A. Early childhood wheezing symptoms in relation to plasma selenium in pregnant mothers and neonates. Clin Exp Allergy. 2007;37:1000–1008. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2007.02757.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Devereux G, Lionjua AA, Turner SW, Craig LCA, McNeill G, Martindale S, Helms PJ, Seaton A, W ST. Maternal vitamin D intake during pregnancy and early childhood wheezing. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85:853–859. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/85.3.853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Martindale S, McNeill G, Devereux G, Campbell D, Russell G, S A. Antioxidnat intake in pregnancy in relation to wheeze and eczema in the first two years of life. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171:121–128. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200402-220OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Devereux G, Turner SW, Craig LC, McNeill G, Martindale S, Harbour PJ, Helms PJ, Seaton A. Low maternal vitamin E intake during pregnancy is associated with asthma in 5-year-old children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174(5):499–507. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200512-1946OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Litonjua AA, Rifas-Shiman SL, Ly NP, Tantisira KG, Rich-Edwards JW, Camargo CA, Jr, Weiss ST, Gillman MW, Gold DR. Maternal antioxidant intake in pregnancy and wheezing illnesses in children at 2 y of age. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84(4):903–911. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/84.4.903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Martindale S, McNeill G, Devereux G, Campbell D, Russell G, Seaton A. Antioxidant intake in pregnancy in relation to wheeze and eczema in the first two years of life. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171(2):121–128. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200402-220OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Haberg SE, London SJ, Stigum H, Nafstad P, Nystad W. Folic acid supplements in pregnancy and early childhood respiratory health. Arch Dis Child. 2009;94(3):180–184. doi: 10.1136/adc.2008.142448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Whitrow MJ, Moore VM, Rumbold AR, Davies MJ. Effect of supplemental folic acid in pregnancy on childhood asthma: a prospective birth cohort study. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;170(12):1486–1493. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martinussen M, Risnes K, Jacobsen G, Bracken M. No increased risk for asthma in children aged six observed among mothers who used folic acid supplementation in early pregnancy. Under Review. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chanmugam P, Guthrie JF, Cecilio S, Morton JF, Basiotis PP, Anand R. Did fat intake in the United States really decline between 1989–1991 and 1994–1996? J Am Diet Assoc. 2003;103(7):867–872. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8223(03)00381-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nielsen SJ, Siega-Riz AM, Popkin BM. Trends in energy intake in U.S. between 1977 and 1996: similar shifts seen across age groups. Obes Res. 2002;10(5):370–378. doi: 10.1038/oby.2002.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Briefel RR, Johnson CL. Secular trends in dietary intake in the United States. Annu Rev Nutr. 2004;24:401–431. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.23.011702.073349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cavadini C, Siega-Riz AM, Popkin BM. US adolescent food intake trends from 1965 to 1996. West J Med. 2000;173(6):378–383. doi: 10.1136/ewjm.173.6.378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cruz JA. Dietary habits and nutritional status in adolescents over Europe--Southern Europe. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2000;54 Suppl 1:S29–S35. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1600981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kocyigit A, Armutcu F, Gurel A, Ermis B. Alterations in plasma essential trace elements selenium, manganese, zinc, copper, and iron concentrations and the possible role of these elements on oxidative status in patients with childhood asthma. Biological Trace Element Research. 2004;97(1):31–41. doi: 10.1385/BTER:97:1:31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Narula MK, Ahuja GK, Whig J, Narang AP, Soni RK. Status of lipid peroxidation and plasma iron level in bronchial asthmatic patients. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. 2007;51(3):289–292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ekmekci OB, Donma O, Sardogan E, Yildirim N, Uysal O, Demirel H, Demir T. Iron, nitric oxide, and myeloperoxidase in asthmatic patients. Biochemistry (Mosc) 2004;69(4):462–467. doi: 10.1023/b:biry.0000026205.89894.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]