Abstract

Septins are conserved GTP-binding proteins that assemble into hetero-oligomeric complexes and higher-order structures such as filaments, rings, hourglasses or gauzes. Septins are usually associated with a discrete region of the plasma membrane and function as a cellular scaffold or diffusion barrier to effect cytokinesis, cell polarity, and many other cellular functions. Recent structural studies of septin complexes have provided mechanistic insights into septin filament assembly, but key questions about the assembly, dynamics, and function of different septin cellular structures remain largely unanswered.

Introduction

Septins were initially discovered in the 1970s in the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae as “neck filaments” encircling the mother-bud neck (Figure 1, A and B) 1. Septins are GTP-binding proteins that are conserved in organisms ranging from yeast to humans, with a notable absence in plants 2. The number of septin genes varies widely in different organisms, with two in Caenorhabditis elegans, seven in S. cerevisiae, and 14 in humans 2. Septins form hetero-oligomeric complexes, which are further assembled into different higher-order structures, such as filaments and rings, that are either associated with other cytoskeletal networks (actin and tubulin) or localized to a discrete region of the plasma membrane to act as a cellular scaffold and/or diffusion barrier to affect diverse cellular functions, including cytokinesis, mitosis, exocytosis, apoptosis, neuronal spine morphogenesis, spermiogenesis, and several checkpoint pathways 3-6. Overexpression or mutations of the septins are associated with serious human diseases, such as cancer, neurodegenerative diseases, and infertility 6. Despite significant progress made in the last few years, many key questions regarding septin structure and function remain unanswered. Here, we review our current knowledge about the assembly, dynamics, and function of the septins, with a focus on the budding yeast system.

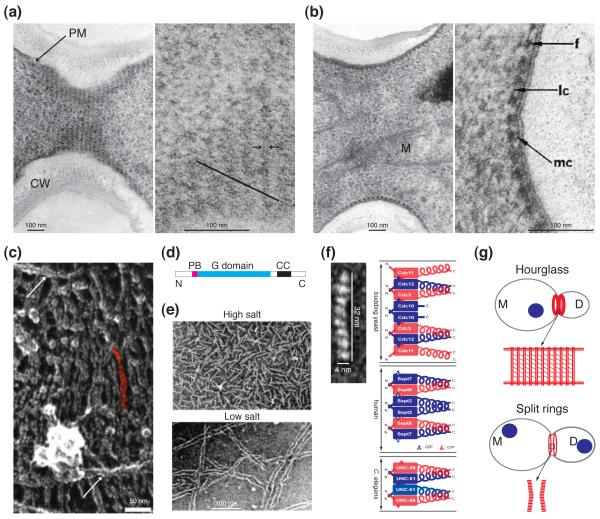

Fig. 1.

Structures of septin complexes and higher-order assemblies in budding yeast and beyond. (a) Left: concentric rings of septin filaments in a septin hourglass visualized in a grazing section of the mother-bud neck (scanned from the original EM picture published in [1]; courtesy of B. Byers). CW, cell wall; PM, plasma membrane. Right: higher magnification of a portion of the image at the left showing diagonal short filaments (parallel to the black line) involved in connecting the rings of septin filaments in the hourglass (reproduced from [1] by copyright permission). (b) Left: septin filaments of an hourglass visualized in a transverse section of the mother-bud neck showing close association of the filaments with the PM (scanned from the original EM picture published in [1]; courtesy of B. Byers). M, mitochondrion. Right: higher magnification of a portion of the image at the left showing interactions of the septin filaments with themselves and the PM. f, filaments; lc, lateral connections; mc, membrane connections (reproduced from [1] by copyright permission). (c) A portion of the septin “gauze” (presumably from the hourglass structure at the mother-bud neck) from a piece of isolated cell cortex visualized by rapid-freeze and deep-etch EM (reproduced from [17] with permission). Arrow, long paired filaments. A single pair of filaments is highlighted in red. (d) Motifs of a generic septin molecule. PB, polybasic region; G domain, guanine nucleotide binding domain; CC, coiled-coil region; N and C, N and C termini of a septin. (e) Native septin complexes (High salt) and their assembled paired filaments (Low salt) visualized by negative-stain EM (reproduced from [12] by copyright permission). (f) Left: septin subunit arrangement in the recombinant septin complex Cdc3/Cdc10/Cdc11/Cdc12 (reproduced from [15] with permission). Right: comparison of the structures of the septin complexes from budding yeast (top), human (middle), and C. elegans (bottom). Blue and red rectangle boxes, the G domain of a septin; blue and red coils, the coiled-coil region of a septin; N and C, the N- and C-termini of a septin. The guanine nucleotides (GDP or GTP) bound in the mammalian, but not the budding yeast and C. elegans, septin complexes are known and thus indicated. (g) Models for the arrangements of septin filaments in the septin hourglass (the “septin-gauze” model) and the split septin rings. Top: the septin hourglass (see the enlarged boxed area) is chiefly made of paired septin filaments (vertically arrayed double red lines) in the form of concentric rings or a spiral that are inter-connected by short filaments (diagonally arrayed thin red lines) as well as some long paired septin filaments (horizontal double red lines). M, mother; D, daughter; Blue circle, nucleus. Bottom: the split septin rings (see the enlarged boxed area) consist of an array of short septin filaments (red lines) in parallel to the long mother-daughter axis.

Architecture of septin complex and higher-order assemblies

The structure and assembly of septins have been discussed in great detail recently 5, 7. Here, we provide a brief summary and highlight new discoveries and major questions. All septins share a basic structure (Figure 1D): a variable N-terminal region, a polybasic region that binds to phospholipids, and a conserved GTP-binding domain. Most septins also contain a predicted coiled-coil domain in their C-termini. Recombinant septins 8-11 or septins purified from budding yeast 12, Drosophila 13, and mammalian cells 11 form rod-shaped hetero-oligomeric complexes (Figure 1E, high salt; and 1F), which polymerize end-to-end into long paired linear filaments (Figure 1E, low salt). These filaments are further assembled into other higher-order structures, such as rings (Figure 2, 0 min), hourglasses (Figure 1, A and B; and Figure 2, 27 and 81 min) or gauzes (Figure 1C).

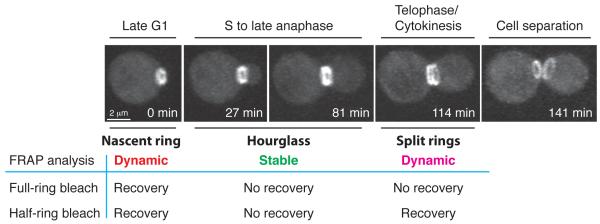

Fig. 2.

Septin organization and dynamics during the cell cycle in budding yeast. After the launch of a new cell cycle in late G1, a septin ring is assembled at the presumptive bud site (0 min). This nascent septin ring is dynamic by FRAP analysis. Upon bud emergence in S phase, the septin ring is converted into a stable hourglass structure, which is maintained at the bud neck during polarized bud growth from S to late anaphase (27 and 81 min). Around the onset of cytokinesis in telophase, the septin hourglass is split into two dynamic cortical rings sandwiching the division machinery (114 min). The septin rings remain at the old division sites for both the mother and the daughter cells until the next round of budding when the “old rings” are disassembled while the new rings are assembled at the presumptive bud site. The transitions in septin organization during the cell cycle are regulated by CDK/cyclins, protein kinases and phosphatases etc (see text for details). Image acquisition and processing for this figure (courtesy of S. Okada): a wild-type haploid cell carrying GFP-tagged Cdc3 was analyzed by 3D spin-disk time-lapse microscopy (20 Z-sections of 0.3 - μm were collected for each time point; interval, 3 - min). The images shown above are snap-shots of 3D reconstructions of the cell from selected time points of a time-lapse series and at an appropriate angle of rotation to show septin structures of interest.

The assembly of septin complexes from mammalian cells 14, C. elegans 9, and budding yeast 15 requires conserved interactions between adjacent guanine nucleotide-binding domains (G interface) as well as the N- and C-terminal extensions (NC interface) (Figure 1F). Despite having different numbers of septins in the stable complex, the overall mechanism underlying septin complex formation and filament assembly is similar in different organisms (Figure 1F). Interestingly, filament assembly by the C. elegans and mammalian septin complexes involves G-interface interactions between the septin building blocks while filament assembly by the budding yeast septin complexes involves NC-interface interactions 9, 14, 15. The significance of this difference is unknown.

The function of the coiled-coil (CC) region of the septins is not entirely clear. Though the CC region is not required for the assembly of some septin complexes 14, abundant evidence indicates that interactions between the CC regions of neighboring septin subunits play a critical role in stabilizing septin complex and filament assembly 8-10, 16. In addition, CC interactions are thought to mediate filament pairing that is frequently observed in vitro and in vivo (Figure 1, A, C, and E) 1, 12, 15, 17, 18.

What is the function of GTP binding and hydrolysis by the septins? Nucleotide binding appears to play a structural role in septin function 10, 11, 13, 19-21. For example, it could help septins fold into a correct conformation for septin complex and filament assembly, akin to the GTP binding by the α-tubulin subunit of the αβ heterodimers 19. In contrast, the function and mechanism of GTP hydrolysis remains elusive. Comparison of the crystal structures of the GDP- and GTP-bound forms of the mammalian Sept2 has revealed a critical residue, threonine (Thr)-78, involved in GTP binding and hydrolysis 14, 22. The Thr-78 is conserved only in a subset of septins 22. For example, mammalian Sept2 and Sept7 have the Thr residue but Sept6 does not. In budding yeast, a corresponding Thr residue is conserved in the septins Cdc10 (Thr-74) and Cdc12 (Thr-75) but not Cdc3, Cdc11, and Shs1, which is consistent with the observed GTPase activities displayed by individual septins 16. Mutational change of the Thr into alanine in CDC10 or CDC12 causes temperature-sensitive growth, demonstrating the importance of this residue in septin functions 22. However, the Thr-78 mutant of mammalian Sept2 is deficient in both GTP binding and hydrolysis, and the Thr mutants of Cdc10 and Cdc12 have not been biochemically characterized, making it difficult to assign functional significance specifically to GTP hydrolysis.

In principle, the GTPase activity of the septins could be stimulated by GTPase-activating proteins or by polymerization 5, 23. To date, evidence supporting either possibility is lacking. Interestingly, Orc6, part of the origin recognition complex for DNA replication in Drosophila, interacts with the septin complex and plays an essential role in cytokinesis 24. Orc6 stimulates the GTPase activity of the septin complex and promotes septin filament assembly or disassembly in the absence or presence of exogenously added GTP, respectively 25. However, the mechanism underlying the Orc6 activities remains to be determined.

The architecture and assembly mechanism for other higher-order structures such as septin rings and hourglasses or gauzes are largely unknown. Based on biochemical and EM studies 1, 12, 15, 17, the septin hourglass at the mother-bud neck prior to cytokinesis likely possesses a “gauze-like” structure consisting mainly of circumferential rings of paired septin filaments that are connected by many intersecting short filaments and a few long filaments (Figure 1G). The molecular basis for the existence of the three types of filaments (the paired ring filaments and the putative intersecting short and long filaments) is not known, although different septin complexes 15, 26, post-translational modifications of septins, and septin-associated regulators may account for the assembly of distinct types of septin filaments. The septin gauze model is supported by the striking observation that PIP2 (phosphatidylinositol-4,5-biphosphate)-containing monolayer promotes “septin mesh” assembly, which involves cross-linking of long paired septin filaments by short septin filaments. And the cross-linking depends on the C-terminal extension of Cdc11 18.

In the context of the gauze model (Figure 1G), it is possible that the newly assembled septin ring and the subsequent septin hourglass at the mother-bud neck may have an overall similar pattern of filament arrangement but differ mainly in filament quantity, with the ring having far fewer filaments than the hourglass. At the end of mitosis, the septin hourglass is instructed by a cell cycle signal (see the next section) to split into two cortical rings. In the proposed gauze model, during septin hourglass splitting, the septin filaments in the circumferential rings may be selectively disassembled and re-assembled into short filaments that are parallel to the mother-daughter axis. This would be consistent with an observed 90° rotation of the GFP probe in GFP-tagged septin filaments associated with the splitting event 27. The validity of the septin gauze model requires further investigation.

Septin organization, dynamics and regulation during the cell cycle

In budding yeast, septins clearly undergo cell cycle-triggered organizational changes (Figure 2) 4, 5, 7. Upon the start of a cell cycle, a nascent septin ring is assembled at the presumptive bud site (Figure 2, 0 min). This ring is dynamic as indicated by fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) 28, 29. Coincident with bud emergence or shortly after, the septin ring expands into a stable hourglass that spans the neck region between the mother and the daughter compartments (Figure 2, 27 and 81 min). Around the onset of cytokinesis, the septin hourglass is split into two dynamic rings that sandwich the cytokinesis machinery (Figure 2, 114 and 141 min). Similar morphological and dynamic changes in septin structures are also observed during the budding cycle of the dimorphic fungus Candida albicans 30. In contrast to S. cerevisiae and C. albicans, cytokinesis in the dimorphic fungus Ustilago maydis is accompanied by a unique change in septin higher-order structures, going from an hourglass to a single cortical ring 31.

Septin ring biogenesis

The most commonly observed septin higher-order structures in different organisms are small rings (0.5 – 3.5 μm in diameter), such as those formed at the division site of various fungi 30-35, the base of dendritic spines in hippocampal neurons 36, 37, the annulus of spermatozoa 38, 39, and the base of primary cilia 40. These rings are thought to function as diffusion barriers and/or cellular scaffolds to maintain distinct membrane domains.

Despite a host of cellular functions associated with the septin ring, the underlying mechanism for its biogenesis remains unknown in any organism. Here, we discuss a model of how Cdc42 may control septin ring assembly in S. cerevisiae. Cdc42, a master regulator of eukaryotic cell polarity 41, 42, controls polarized assembly of actin cables and the septin ring at the same time and location 42. Actin cables guide exocytosis components to the presumptive bud site (PBS) to establish a polarized membrane domain within the septin ring 42. Upon bud emergence, actin cables and the septin ring are spatially segregated, with the cables aligned towards the bud tip or cortex to continue its guiding role in vesicle transport, whereas the septin ring is left at the base of the bud to maintain the bud-neck integrity and restrict polarity determinants to the bud cortex. In S. cerevisiae, Cdc42-controlled septin ring assembly can be divided into three general steps: septin recruitment and membrane association, ring assembly, and ring maturation (Box 1, Figure 3) 4, 28, 42, 43. The core concept of small GTPase-controlled septin ring assembly and mutual enhancement of actin and septin organization during cell polarization is likely applicable to other systems.

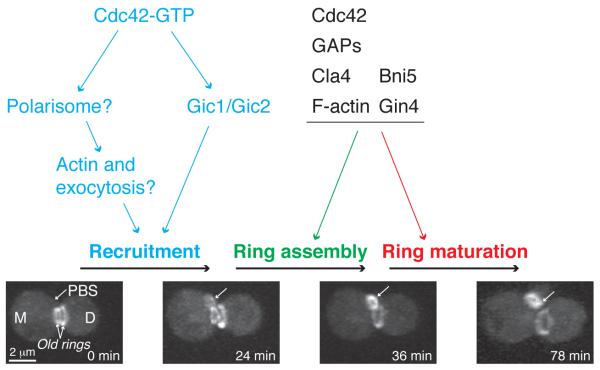

Box 1. A model for Cdc42-controlled septin ring assembly in yeast.

Cdc42 controls septin ring assembly via three steps: septin recruitment and membrane association, ring assembly, and ring maturation (Figure 3). Step1: septin recruitment and membrane association. During this stage, septin complexes are continuously recruited to the PBS to increase local concentration for filament and ring assembly. Newly recruited septins are usually in the form of a disorganized “cloud” or “patch” with stripes of filament-like structures 43. Septin recruitment completely depends on Cdc42 43, 44. Gic1 and Gic2, a pair of structurally related, CRIB (Cdc42/Rac Interactive Binding) motif-containing effectors of Cdc42, interact directly with the septins and are essential for septin recruitment at 37°C 43. At the low temperatures, the polarisome 45, which contains the formin Bni1 (also an effector of Cdc42) as its centerpiece 42, may define a parallel pathway for septin recruitment. Once recruited to the PBS, the septin complexes are closely associated with the plasma membrane (PM) via interactions between the polybasic region of the septins and the phospholipids of the PM 46-49. The strength of these interactions will increase during the process of septin ring assembly and maturation, as more septin subunits are incorporated into the higher-order structures. Transmembrane proteins may also be involved in septin-membrane interaction in yeast, spermatozoa and myelinating glia 50-52, which resembles the transmembrane proteins (occludins, claudins etc.) in the tight junctions of epithelial cells that anchor cortical actin filaments to the PM via adaptor proteins 53. Step2: ring assembly. The recruited septins at the PBS undergo a major organizational change from a disorganized septin cloud to an organized smooth ring of ~ 1.0 μm in diameter within minutes (Figure 3, 24 and 36 min) 43. In fibroblasts, when the stress fibers are disrupted by actin depolymerization drugs, the septin filaments are organized into small rings of ~0.6 μm in diameter, suggesting that septin filaments may possess an intrinsic propensity to bend into small rings 11. The variation in ring size, from the 0.6 μm in spermatozoa to the 1 μm in budding yeast and the ~3.5 μm ring in fission yeast, may reflect distinct angles of bending by distinct septin complexes 14 and/or modulations of a default ring size of ~0.6 μm by distinct regulators. The cycling of Cdc42 between its active GTP-bound and inactive GDP-bounds states is critical for septin ring assembly 54. Consistently, the GTPase-activating proteins (GAPs) for Cdc42 may promote septin ring assembly by facilitating the “unloading” of septin complexes from the recruitment pathways via their GAP activity 28, 33, 54, 55. The PAK Cla4, an effector of Cdc42, also regulates septin ring assembly by directly phosphorylating a subset of septins 16. Step 3: ring maturation. Upon bud emergence, the dynamic septin ring at the PBS is transformed into a stable septin hourglass at the mother-bud neck. Although the mechanism underlying this transformation remains unknown, the LKB1-related kinase Elm1 56, one of its target kinases, Gin4 57, and two other septin-associated proteins (Bni5 and Nap1) 58, 59 appear to be involved, as cells lacking any of these factors can assemble a seemingly normal septin ring, but not a normal hourglass.

Fig. 3.

A model for Cdc42-controlled septin ring assembly in budding yeast. Budding yeast undergoes asymmetric division by default, which means that at the time of cytokinesis and cell separation, the daughter cell (D, 0 min) is substantially smaller than the mother cell (M, 0 min). Consequently, the mother cell enters a new cell cycle immediately after cell division whereas the daughter cell stays in G1 for longer period to reach a critical cell mass required for the launch of a new cell cycle. Thus, in this figure, only the septin ring assembly at the mother side is depicted. We propose that septin ring assembly at the presumptive bud site (PBS, 0 min) involves three steps: septin recruitment and membrane association, ring assembly, and ring maturation (see text for details). Single arrows, the PBS and the septin structures of interest (“septin cloud”, 24 min; “septin ring”, 36 min; “septin hourglass”, 78 min). Image acquisition and processing for this figure are the same as described for Figure 2.

Regulation of septin organization and dynamics

The mechanism underlying cell cycle-triggered transitions in septin organization or dynamics in any system remains largely unknown. In S. cerevisiae, cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs), polarity factors, and post-translational modifications of the septins (phosphorylation and SUMOylation) are involved 7. G1 cyclin-bound CDK plays a dual role in initial septin ring assembly. One role is an indirect, but essential, function that is mediated by the polarity factor Cdc42 (Figure 3) 43, 44, 60, and the other role is via direct phosphorylation of the septins 61. The Nim1-related kinase Gin4 is associated with the septins at the bud neck throughout the cell cycle 62, and Gin4 directly phosphorylates Shs1 63. This phosphorylation likely affects septin ring-to-hourglass transition 7, 62, 64. Interestingly, Gin4 and CDK/G1 cyclin act sequentially to phosphorylate Cdc11 to control septin ring and/or hourglass assembly that is required for proper hyphal development in C. albicans 65. Together, these observations suggest that the initial septin ring and hourglass assembly is regulated by phosphorylation involving localized kinases exerting local effects on the assembly of a subset of septin structures, a point that is vividly demonstrated in the filamentous fungus Ashbya gossypii 34.

Septin hourglass splitting is controlled by the mitotic exit network (MEN) 44, 66, 67, a kinase cascade that is activated by the small GTPase Tem1 68, 69. The MEN controls the mitotic exit by reducing CDK activity, and also controls cytokinesis by a mechanism that is yet to be fully elucidated. CDK inactivation at the mitotic exit appears to be sufficient for septin hourglass splitting 44, 67. The core components of the MEN pathway are conserved in other fungi and mammalian cells 68, 69. Interestingly, the hourglass-to-single-ring transition that occurs during cytokinesis in the dimorphic fungus U. maydis involves disassembly of the old hourglass and re-assembly of the new septin ring, and this dramatic transition depends on the germinal center kinase Don3 31. Don3 is homologous to Sid1, an essential kinase in the septation initiation network (SIN, equivalent to the MEN in S. cerevisiae) in the fission yeast S. pombe. Inactivation of CDK is required for the proper localization of Sid1 70 and thus for its localized kinase activity. It is unknown whether Sid1 is required for septin ring splitting during cytokinesis in S. pombe. Nonetheless, these observations suggest that inactivation of CDK at the end of mitosis is essential for septin hourglass-to-ring transition in diverse organisms, which may define a unifying mechanism underlying septin re-arrangements during cytokinesis.

After cytokinesis and cell separation, the old septin ring at the division site is disassembled and a new septin ring is formed adjacently (Figure 3, 24 and 36 min) 43. Timely disassembly of the old septin ring is presumably important for the assembly and function of the new septin ring at the PBS, as pulse labeling of septin subunits indicates that septin subunits are re-cycled from the old ring to the new ring during successive cell divisions 71. Disassembly of the old septin rings appears to be regulated by protein phosphatase 2A 29. In addition, septins are major targets of SUMOylation during mitosis in S. cerevisiae 72. However, the significance of this modification remains unclear 72, 73.

Mammalian septins are also phosphorylated by various kinases such as CDK5 74, casein kinase II 75, cGMP-dependent protein kinase PKG-I 76, and dual-specificity tyrosine phosphorylation-regulated kinase 1A 77. In addition, Sept5 is ubiquitinated by the E3 ligase Parkin, which regulates the degradation of Sept5 78. The functional consequences of these post-translational modifications have been studied to various degrees, but it remains unknown how the modifications may contribute to the assembly and disassembly of septin higher-order structures.

Septin functions: scaffold model versus diffusion-barrier model

Two non-mutually exclusive models have been proposed to account for the diverse functions of the septins. The scaffold model posits that septin structure serves as a cellular scaffold that tethers proteins at a specific cellular location to perform their unique functions 79, 80. The diffusion-barrier model posits that septin structure functions as a diffusion barrier at a discrete region of the PM that prevents membrane and membrane-associated proteins from crossing the membrane boundary 81, 82. Here, we discuss different cellular functions in the context of these models, focusing on cytokinesis in budding yeast.

Scaffold model cytokinesis, exocytosis, checkpoint pathways, and other cellular functions

Cytokinesis in fungi and animal cells involves the function of a contractile actomyosin ring (AMR), membrane trafficking coupled with extracellular matrix remodeling, and spatiotemporal coordination of these processes. In budding yeast, the sole type-II myosin, Myo1, co-localizes with the septin ring at the PBS, and with the septin hourglass at the mother-bud neck from bud emergence until septin hourglass splitting 83, 84, which coincides with the onset of cytokinesis 66. The split septin rings, then sandwiches, the AMR and other components of the cytokinesis machinery 44, 66, 85. Before the septin hourglass splitting, the neck localization of Myo1 and many other cytokinesis proteins depends on the septins 68. Strikingly, in a septin mutant (cdc3-ts) where the septin hourglass at the mother-bud neck is disrupted, septins (such as Cdc12) and Myo1 are still co-localized at other cortical sites, highlighting their close association 86. These observations suggest that the septin ring and the hourglass likely function as a scaffold to localize and concentrate cytokinesis proteins at the division site for AMR assembly prior to cytokinesis.

Septins also function as a cellular scaffold in many other processes. For example, in budding yeast, the septin hourglass is involved in bud site selection by anchoring landmark proteins that specify the next budding site 42. The septin hourglass is also involved in chitin deposition. During early stages of budding, chitin synthase III, including its catalytic subunit Chs3 and its activator Chs4, is localized to the mother side of the neck in a septin-dependent manner 87. This spatiotemporally restricted chitin synthesis is required for maintaining the neck integrity during polarized bud growth 88. Because Chs3 undergoes dynamic cycling between the neck and chitosomes (specialized trans-Golgi network/early endosome-like structures) via exocytosis and endocytosis, respectively 89, 90, the septin hourglass can also be considered as a scaffold or platform for localized exo- and endocytosis. Finally, the septin scaffold plays important roles in several checkpoint pathways, including the morphogenesis checkpoint [see review 91 for details], the spindle position checkpoint 92 and the DNA damage checkpoint 93, by tethering factors involved in these processes at the mother-bud neck.

Septins also function as a scaffold during cytokinesis in mammalian cells. Septins interact directly with non-muscle myosin-II, and disruption of this interaction results in the dissociation of myosin-II from Rho-activated myosin kinases and citron kinase during cytokinesis, suggesting that septins may promote efficient activation of myosin-II by bringing the myosin and its activating kinases together during cytokinesis 94. Septins may also function as a scaffold during exocytosis. In rat brains and neuroendocrine PC12 cells, septins are associated with the exocyst, a conserved multi-subunit protein complex required for the tethering of post-Golgi vesicles to the PM, and appear to promote polarized neurite outgrowth 95, 96. Because septins also interact with the PM and syntaxins 46, 97, septins may act as a scaffold to facilitate vesicle tethering by interacting with multiple exocytosis factors at the PM 98.

Despite nearly 100 proteins that localize to the mother-bud neck in a septin-dependent manner in S. cerevisiae 3, 7, very few have been demonstrated to interact directly with individual septins. Perhaps septin higher-order structures such as septin complexes, filaments, rings, or hourglasses are required for interactions with specific non-septin proteins. This issue must be addressed in order to gain a better understanding of the septin scaffold model.

Diffusion-barrier model: cytokinesis, cell polarization, and other cellular functions

During cytokinesis in budding yeast (Figure 2, 114 min), the split septin rings sandwich the AMR and other cortical factors at the division site. Such factors include the polarisome component Spa2, the exocyst subunit Sec3 and the secretory cargo Chs2 (chitin synthase II) 85. Conditional disruption of the septin rings during cytokinesis causes the dispersal of cortical factors from the division site, resulting in the inhibition of cytokinesis and cell separation 85. These observations led to the idea that the septin rings function as diffusion barriers that restrict diffusible cytokinesis factors to the division site 85. A similar function has been proposed for mammalian septins during cytokinesis 99.

During polarized bud growth, the septin hourglass is also thought to function as a diffusion barrier to restrict polarity and exocytosis factors 81, transmembrane proteins 82, and other cortical proteins such as Lte1, an activator of the mitotic exit network, to the bud cortex 92. Similarly, a septin-based diffusion barrier is required for the compartmentalization of the endoplasmic reticulum membrane during polarized bud growth 100 and for preventing the segregation of aging factors, such as the episomal DNA circles, from the mother cell to the bud 101.

Similar to the budding process in S. cerevisiae, spine morphogenesis in hippocampal neurons involves polarized assembly of two cellular structures, actin arrays and a septin ring, initially at the same cellular location, which are then spatially segregated with the actin arrays pointing towards the spine cortex and the septin ring retaining at the base of the spine to mediate the establishment and maintenance of polarized membrane domains, respectively 36, 37. Recently, a septin ring at the base of the primary cilium in mouse kidney cells and embryonic fibroblasts as well as Xenopus is thought to function as a diffusion barrier in restricting membrane proteins, including signaling receptors, in the cilium 40, 102, very much like the septin ring in the annulus of spermatozoa, which separates the membrane domains between the midpiece and the principal piece of the sperm tail 38, 39, 103.

Despite the implication of septin rings as diffusion barriers in a variety of settings, it is unknown in any system how the septin ring interacts with the PM to generate a physical barrier or alternatively, how the septin ring may act as a scaffold to enable the generation of a diffusion barrier by non-septin proteins. This central issue must be addressed in order to gain a deeper understanding of the diffusion-barrier model.

Concluding remarks

Biological systems are, in essence, three dimensional maps of interconnected cellular structures that perform specific functions. In this context, many key questions regarding the structure-function relationships of the septins remain unanswered. For example, the basic rules governing the number, composition, and assembly of distinct septin complexes for a given organism or cell type remain unknown. The role of GTP binding and hydrolysis in septin filament assembly (and, possibly, other aspects of septin function) is poorly understood. The architecture and assembly mechanism of septin ring and hourglass are largely unknown. For example, it is a mystery how the septin hourglass, which lacks apparent structural polarity, is regulated to allow asymmetric binding of different proteins to discrete regions of the hourglass [see reviews 3, 7 for comprehensive lists of protein localization patterns at the mother-bud neck and for more discussions on this issue]. It also remains to be determined whether common principles and molecular pathways are involved in the simultaneous assembly of polarized actin arrays and a septin ring at a given location in yeast, neurons, and spermatozoa for the purpose of polarity establishment and maintenance.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. S. Okada for generating live-cell images presented in figures 2 and 3 and Dr. B. Byers for scanning the original EM images for figure 1; Drs. J. Thorner, M. Longtine, M. McMurray, C. Wloka, N. Savage, and A. Goryachev for critically reading the manuscript; Drs. B. Byers, A. Rodal, C. Field, J. Thorner, and E. Nogales for their permission to reproduce original images; and the members of the Bi laboratory for discussions. This work is supported by grant GM59216 from the National Institutes of Health and grant RSG-02-039-01-CSM from the American Cancer Society to E. Bi.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Byers B, Goetsch L. A highly ordered ring of membrane-associated filaments in budding yeast. J. Cell Biol. 1976a;69:717–721. doi: 10.1083/jcb.69.3.717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pan F, et al. Analysis of septins across kingdoms reveals orthology and new motifs. BMC Evol. Biol. 2007;7:103. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-7-103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gladfelter AS, et al. The septin cortex at the yeast mother-bud neck. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2001;4:681–689. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(01)00269-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Longtine M, Bi E. Regulation of septin organization and function in yeast. Trends Cell Biol. 2003;13:403–409. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(03)00151-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weirich CS, et al. The septin family of GTPases: architecture and dynamics. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008;9:478–489. doi: 10.1038/nrm2407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hall PA, et al. The Septins. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 7.McMurray MA, Thorner J. Septins: molecular partitioning and the generation of cellular asymmetry. Cell Div. 2009;4:18. doi: 10.1186/1747-1028-4-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Versele M, et al. Protein-protein interactions governing septin heteropentamer assembly and septin filament organization in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2004;15:4568–4583. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-04-0330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.John CM, et al. The Caenorhabditis elegans septin complex is nonpolar. EMBO J. 2007;26:3296–3307. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sheffield PJ, et al. Borg/septin interactions and the assembly of mammalian septin heterodimers, trimers, and filaments. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:3483–3488. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209701200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kinoshita M, et al. Self- and actin-templated assembly of mammalian septins. Dev. Cell. 2002;3:791–802. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00366-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frazier JA, et al. Polymerization of purified yeast septins: evidence that organized filament arrays may not be required for septin function. J. Cell Biol. 1998;143:737–749. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.3.737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Field CM, et al. A purified Drosophila septin complex forms filaments and exhibits GTPase activity. J. Cell Biol. 1996;133:605–616. doi: 10.1083/jcb.133.3.605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sirajuddin M, et al. Structural insight into filament formation by mammalian septins. Nature (London) 2007;449:311–315. doi: 10.1038/nature06052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bertin A, et al. Saccharomyces cerevisiae septins: supramolecular organization of heterooligomers and the mechanism of filament assembly. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:8274–8279. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803330105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Versele M, Thorner J. Septin collar formation in budding yeast requires GTP binding and direct phosphorylation by the PAK, Cla4. J. Cell Biol. 2004;164:701–715. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200312070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rodal AA, et al. Actin and septin ultrastructures at the budding yeast cell cortex. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2005;16:372–384. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-08-0734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bertin A, et al. Phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate promotes budding yeast septin filament assembly and organization. J. Mol. Biol. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.10.002. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vrabioiu AM, et al. The majority of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae septin complexes do not exchange guanine nucleotides. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:3111–3118. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310941200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Farkasovsky M, et al. Nucleotide binding and filament assembly of recombinant yeast septin complexes. Biol. Chem. 2005;386:643–656. doi: 10.1515/BC.2005.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nagaraj S, et al. Role of nucleotide binding in septin-septin interactions and septin localization in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2008;28:5120–5137. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00786-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sirajuddin M, et al. GTP-induced conformational changes in septins and implications for function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:16592–16597. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902858106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gasper R, et al. It takes two to tango: regulation of G proteins by dimerization. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2009;10:423–429. doi: 10.1038/nrm2689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chesnokov IN, et al. A cytokinetic function of Drosophila ORC6 protein resides in a domain distinct from its replication activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:9150–9155. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1633580100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huijbregts RP, et al. Drosophila Orc6 facilitates GTPase activity and filament formation of the septin complex. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2009;20:270–281. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-07-0754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Iwase M, et al. Shs1 plays separable roles in septin organization and cytokinesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 2007;177:215–229. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.073007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vrabioiu AM, Mitchison TJ. Structural insights into yeast septin organization from polarized fluorescence microscopy. Nature (London) 2006;443:466–469. doi: 10.1038/nature05109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Caviston JP, et al. The role of Cdc42p GTPase-activating proteins in assembly of the septin ring in yeast. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2003;14:4051–4066. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-04-0247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dobbelaere J, et al. Phosphorylation-dependent regulation of septin dynamics during the cell cycle. Dev. Cell. 2003;4:345–357. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00061-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gonzalez-Novo A, et al. Sep7 is essential to modify septin ring dynamics and inhibit cell separation during Candida albicans Hyphal Growth. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2008;19:1509–1518. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-09-0876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bohmer C, et al. The germinal centre kinase Don3 triggers the dynamic rearrangement of higher-order septin structures during cytokinesis in Ustilago maydis. Mol. Microbiol. 2009;74:1484–1496. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06948.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Berlin A, et al. Mid2p stabilizes septin rings during cytokinesis in fission yeast. J. Cell Biol. 2003;160:1083–1092. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200212016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kadota J, et al. Septin ring assembly requires concerted action of polarisome components, a PAK kinase Cla4p, and the actin cytoskeleton in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2004;15:5329–5345. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-03-0254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.DeMay BS, et al. Regulation of distinct septin rings in a single cell by elm1p and gin4p kinases. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2009;20:2311–2326. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-12-1169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lindsey R, et al. Septins AspA and AspC are important for normal development and limit the emergence of new growth foci in the multicellular fungus Aspergillus nidulans. Eukaryot. Cell. 2010;9:155–163. doi: 10.1128/EC.00269-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xie Y, et al. The GTP-binding protein septin 7 is critical for dendrite branching and dendritic-spine morphology. Curr. Biol. 2007;17:1746–1751. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.08.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tada T, et al. Role of septin cytoskeleton in spine morphogenesis and dendrite development in neurons. Curr. Biol. 2007;17:1752–1758. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.09.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ihara M, et al. Cortical organization by the septin cytoskeleton is essential for structural and mechanical integrity of mammalian spermatozoa. Dev. Cell. 2005;8:343–352. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kissel H, et al. The Sept4 septin locus is required for sperm terminal differentiation in mice. Dev. Cell. 2005;8:353–364. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hu Q, et al. A septin diffusion barrier at the base of the primary cilium maintains ciliary membrane protein distribution. Science. 2010;329:436–439. doi: 10.1126/science.1191054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Etienne-Manneville S. Cdc42--the centre of polarity. J. Cell Sci. 2004;117:1291–1300. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Park HO, Bi E. Central roles of small GTPases in the development of cell polarity in yeast and beyond. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2007;71:48–96. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00028-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Iwase M, et al. Role of a cdc42p effector pathway in recruitment of the yeast septins to the presumptive bud site. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2006;17:1110–1125. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-08-0793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cid VJ, et al. Cell cycle control of septin ring dynamics in the budding yeast. Microbiology. 2001;147:1437–1450. doi: 10.1099/00221287-147-6-1437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sheu YJ, et al. Spa2p interacts with cell polarity proteins and signaling components involved in yeast cell morphogenesis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1998;18:4053–4069. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.7.4053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang J, et al. Phosphatidylinositol polyphosphate binding to the mammalian septin H5 is modulated by GTP. Curr. Biol. 1999;9:1458–1467. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)80115-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Casamayor A, Snyder M. Molecular dissection of a yeast septin: distinct domains are required for septin interaction, localization, and function. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2003;23:2762–2777. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.8.2762-2777.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rodriguez-Escudero I, et al. Reconstitution of the mammalian PI3K/PTEN/Akt pathway in yeast. Biochem. J. 2005;390:613–623. doi: 10.1042/BJ20050574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tanaka-Takiguchi Y, et al. Septin-mediated uniform bracing of phospholipid membranes. Curr. Biol. 2009;19:140–145. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gao XD, et al. Sequential and distinct roles of the cadherin domain-containing protein Axl2p in cell polarization in yeast cell cycle. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2007;18:2542–2560. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-09-0822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Toure A, et al. The testis anion transporter 1 (Slc26a8) is required for sperm terminal differentiation and male fertility in the mouse. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2007;16:1783–1793. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Buser AM, et al. The septin cytoskeleton in myelinating glia. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2009;40:156–166. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2008.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Steed E, et al. Dynamics and functions of tight junctions. Trends Cell Biol. 20:142–149. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gladfelter AS, et al. Septin ring assembly involves cycles of GTP loading and hydrolysis by Cdc42p. J. Cell Biol. 2002;156:315–326. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200109062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Smith GR, et al. GTPase-activating proteins for Cdc42. Eukaryot. Cell. 2002;1:469–480. doi: 10.1128/EC.1.3.469-480.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bouquin N, et al. Regulation of cytokinesis by the Elm1 protein kinase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Cell Sci. 2000;113:1435–1445. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.8.1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Asano S, et al. Direct phosphorylation and activation of a Nim1-related kinase Gin4 by Elm1 in budding yeast. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:27090–27098. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601483200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Altman R, Kellogg D. Control of mitotic events by Nap1 and the Gin4 kinase. J. Cell Biol. 1997;138:119–130. doi: 10.1083/jcb.138.1.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lee PR, et al. Bni5p, a septin-interacting protein, is required for normal septin function and cytokinesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002;22:6906–6920. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.19.6906-6920.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Moffat J, Andrews B. Late-G1 cyclin-CDK activity is essential for control of cell morphogenesis in budding yeast. Nat. Cell Biol. 2004;6:59–66. doi: 10.1038/ncb1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Egelhofer TA, et al. The septins function in G1 pathways that influence the pattern of cell growth in budding yeast. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e2022. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Longtine MS, et al. Role of the yeast Gin4p protein kinase in septin assembly and the relationship between septin assembly and septin function. J. Cell Biol. 1998;143:719–736. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.3.719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mortensen EM, et al. Cell cycle-dependent assembly of a Gin4-septin complex. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2002;13:2091–2105. doi: 10.1091/mbc.01-10-0500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gladfelter AS, et al. Genetic interactions among regulators of septin organization. Eukaryot. Cell. 2004;3:847–854. doi: 10.1128/EC.3.4.847-854.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sinha I, et al. Cyclin-dependent kinases control septin phosphorylation in Candida albicans hyphal development. Dev. Cell. 2007;13:421–432. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lippincott J, et al. The Tem1 small GTPase controls actomyosin and septin dynamics during cytokinesis. J. Cell Sci. 2001;114:1379–1386. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.7.1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Meitinger F, et al. Targeted localization of Inn1, Cyk3 and Chs2 by the mitotic-exit network regulates cytokinesis in budding yeast. J. Cell Sci. 2010;123:1851–1861. doi: 10.1242/jcs.063891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Balasubramanian MK, et al. Comparative analysis of cytokinesis in budding yeast, fission yeast and animal cells. Curr. Biol. 2004;14:R806–818. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Stegmeier F, Amon A. Closing mitosis: the functions of the Cdc14 phosphatase and its regulation. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2004;38:203–232. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.38.072902.093051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Guertin DA, et al. The role of the sid1p kinase and cdc14p in regulating the onset of cytokinesis in fission yeast. EMBO J. 2000;19:1803–1815. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.8.1803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.McMurray MA, Thorner J. Septin stability and recycling during dynamic structural transitions in cell division and development. Curr. Biol. 2008;18:1203–1208. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Johnson ES, Blobel G. Cell cycle-regulated attachment of the ubiquitin-related protein SUMO to the yeast septins. J. Cell Biol. 1999;147:981–993. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.5.981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Johnson ES, Gupta AA. An E3-like factor that promotes SUMO conjugation to the yeast septins. Cell. 2001;106:735–744. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00491-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Amin ND, et al. Cyclin-dependent kinase 5 phosphorylation of human septin SEPT5 (hCDCrel-1) modulates exocytosis. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:3631–3643. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0453-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Huang YW, et al. GTP binding and hydrolysis kinetics of human septin 2. FEBS J. 2006;273:3248–3260. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2006.05333.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Xue J, et al. Septin 3 (G-septin) is a developmentally regulated phosphoprotein enriched in presynaptic nerve terminals. J. Neurochem. 2004;91:579–590. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02755.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sitz JH, et al. The Down syndrome candidate dual-specificity tyrosine phosphorylation-regulated kinase 1A phosphorylates the neurodegeneration-related septin 4. Neuroscience. 2008;157:596–605. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Dong Z, et al. Dopamine-dependent neurodegeneration in rats induced by viral vector-mediated overexpression of the parkin target protein, CDCrel-1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:12438–12443. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2132992100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Chant J, et al. Role of Bud3p in producing the axial budding pattern of yeast. J. Cell Biol. 1995;129:767–778. doi: 10.1083/jcb.129.3.767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Longtine MS, et al. The septins: roles in cytokinesis and other processes. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 1996;8:106–119. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(96)80054-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Barral Y, et al. Compartmentalization of the cell cortex by septins is required for maintenance of cell polarity in yeast. Mol. Cell. 2000;5:841–851. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80324-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Takizawa PA, et al. Plasma membrane compartmentalization in yeast by messenger RNA transport and a septin diffusion barrier. Science. 2000;290:341–344. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5490.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bi E, et al. Involvement of an actomyosin contractile ring in Saccharomyces cerevisiae cytokinesis. J. Cell Biol. 1998;142:1301–1312. doi: 10.1083/jcb.142.5.1301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lippincott J, Li R. Sequential assembly of myosin II, an IQGAP-like protein, and filamentous actin to a ring structure involved in budding yeast cytokinesis. J. Cell Biol. 1998a;140:355–366. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.2.355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Dobbelaere J, Barral Y. Spatial coordination of cytokinetic events by compartmentalization of the cell cortex. Science. 2004;305:393–396. doi: 10.1126/science.1099892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Roh DH, et al. The septation apparatus, an autonomous system in budding yeast. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2002;13:2747–2759. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-03-0158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.DeMarini DJ, et al. A septin-based hierarchy of proteins required for localized deposition of chitin in the Saccharomyces cerevisiae cell wall. J. Cell Biol. 1997;139:75–93. doi: 10.1083/jcb.139.1.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Schmidt M, et al. Septins, under Cla4p regulation, and the chitin ring are required for neck integrity in budding yeast. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2003;14:2128–2141. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-08-0547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ziman M, et al. Chs1p and Chs3p, two proteins involved in chitin synthesis, populate a compartment of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae endocytic pathway. Mol. Biol. Cell. 1996;7:1909–1919. doi: 10.1091/mbc.7.12.1909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Chuang JS, Schekman RW. Differential trafficking and timed localization of two chitin synthase proteins, Chs2p and Chs3p. J. Cell Biol. 1996;135:597–610. doi: 10.1083/jcb.135.3.597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Keaton MA, Lew DJ. Eavesdropping on the cytoskeleton: progress and controversy in the yeast morphogenesis checkpoint. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2006;9:540–546. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2006.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Castillon GA, et al. Septins have a dual role in controlling mitotic exit in budding yeast. Curr. Biol. 2003;13:654–658. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00247-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Smolka MB, et al. An FHA domain-mediated protein interaction network of Rad53 reveals its role in polarized cell growth. J. Cell Biol. 2006;175:743–753. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200605081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Joo E, et al. Mammalian SEPT2 is required for scaffolding nonmuscle myosin II and its kinases. Dev. Cell. 2007;13:677–690. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Hsu S-C, et al. Subunit composition, protein interactions, and structures of the mammalian brain sec6/8 complex and septin filaments. Neuron. 1998;20:1111–1122. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80493-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Vega IE, Hsu SC. The septin protein Nedd5 associates with both the exocyst complex and microtubules and disruption of its GTPase activity promotes aberrant neurite sprouting in PC12 cells. Neuroreport. 2003;14:31–37. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200301200-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Beites CL, et al. The septin CDCrel-1 binds syntaxin and inhibits exocytosis. Nat. Neurosci. 1999;2:434–439. doi: 10.1038/8100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kartmann B, Roth D. Novel roles for mammalian septins: from vesicle trafficking to oncogenesis. J. Cell Sci. 2001;114:839–844. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.5.839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Schmidt K, Nichols BJ. A barrier to lateral diffusion in the cleavage furrow of dividing mammalian cells. Curr. Biol. 2004;14:1002–1006. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.05.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Luedeke C, et al. Septin-dependent compartmentalization of the endoplasmic reticulum during yeast polarized growth. J. Cell Biol. 2005;169:897–908. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200412143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Shcheprova Z, et al. A mechanism for asymmetric segregation of age during yeast budding. Nature (London) 2008;454:728–734. doi: 10.1038/nature07212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Kim SK, et al. Planar cell polarity acts through septins to control collective cell movement and ciliogenesis. Science. 2010;329:1337–1340. doi: 10.1126/science.1191184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Kwitny S, et al. The annulus of the mouse sperm tail is required to establish a membrane diffusion barrier that is engaged during the late steps of spermiogenesis. Biol. Reprod. 82:669–678. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.109.079566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]