Abstract

Once-daily injections of teriparatide initially increase biochemical markers of bone formation and resorption, but markers peak after 6–12 months and then decline despite continued treatment. We sought to determine whether increasing teriparatide doses in a stepwise fashion could prolong skeletal responsiveness. We randomized 52 postmenopausal women with low spine and/or hip bone mineral density (BMD) to either a constant or an escalating subcutaneous teriparatide dose (30 mcg daily for 18 months or 20 mcg daily for 6 months, then 30 mcg daily for 6 months, then 40 mcg daily for 6 months). Serum procollagen I N-terminal propeptide, osteocalcin, and C-terminal telopeptide of type I collagen were assessed frequently. BMD of the spine, hip, radius, and total body was measured every 6 months. Acute changes in urinary cyclic AMP in response to teriparatide were examined in a subset of women in the constant dose group. All bone markers differed significantly between the two treatment groups. During the final six months, bone markers declined in the constant dose group but remained stable or increased in the escalating dose group (all markers, p<0.017). Nonetheless, mean area under the curve did not differ between treatments for any bone marker, and BMD increases were equivalent in both treatment groups. Acute renal response to teriparatide, as assessed by urinary cyclic AMP, did not change over 18 months of teriparatide administration. In conclusion, stepwise increases in teriparatide prevented the decline in bone turnover markers that is observed with chronic administration without altering BMD increases. The time-dependent waning of the response to teriparatide appears to be bone-specific.

Keywords: teriparatide, parathyroid hormone, osteoporosis, bone turnover markers, bone densitometry

1. Introduction

Osteoporosis is a major public health problem and leads to approximately 1.5 million fractures each year in the United States. While anti-resorptive agents such as bisphosphonates can increase bone mineral density (BMD) modestly during the first few years of treatment, most patients continue to have low BMD and many continue to fracture. Anabolic agents such as human parathyroid hormone 1–34 (teriparatide) stimulate new bone formation and therefore have the theoretical potential to restore bone mass and bone strength to normal. In women with postmenopausal osteoporosis, teriparatide increases spine BMD much more than anti-resorptive agents and markedly reduces the incidence of new spine and non-spine fractures. Similar results have been observed in osteoporotic men treated with teriparatide, but the drug rarely restores normal bone mass in patients of either gender.

The complete biologic mechanisms of teriparatide’s anabolic action on bone are still unclear. One perplexing phenomenon observed in multiple clinical trials is that teriparatide-stimulated increases in bone formation dissipate over time. Specifically, biochemical indices of bone formation and resorption peak after 6–12 months of teriparatide therapy and then decline to or toward baseline despite continued treatment. A similar rise and fall of bone turnover markers occurs in animals or osteoporotic women treated with full length human PTH 1–84. Previous studies have shown that increases in bone formation markers in the first six months of PTH therapy are predictive of later BMD increases. Therefore, declining bone marker levels with persistent treatment may be an early indication of decreasing PTH efficacy. The initial rise and subsequent fall in biochemical markers of bone turnover may explain why vertebral BMD increases most rapidly during the first year of teriparatide use, after which the rate of increase slows. The physiologic mechanisms behind these time-dependent changes in skeletal response to teriparatide are unknown as are ways to prevent the decline in bone turnover that occurs after 6–12 months of PTH administration.

We sought to explore this phenomenon of waning skeletal response with a physiologic trial comparing two different teriparatide dosing regimens. We hypothesized that increasing the teriparatide dose in a step-wise fashion might maintain or enhance its effects on bone formation. To this end, we compared the effects of a constant daily teriparatide dose regimen with an escalating dose regimen in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis, while keeping the total dose received by each group similar. We also explored whether renal responsiveness to teriparatide changes after prolonged treatment.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Study subjects

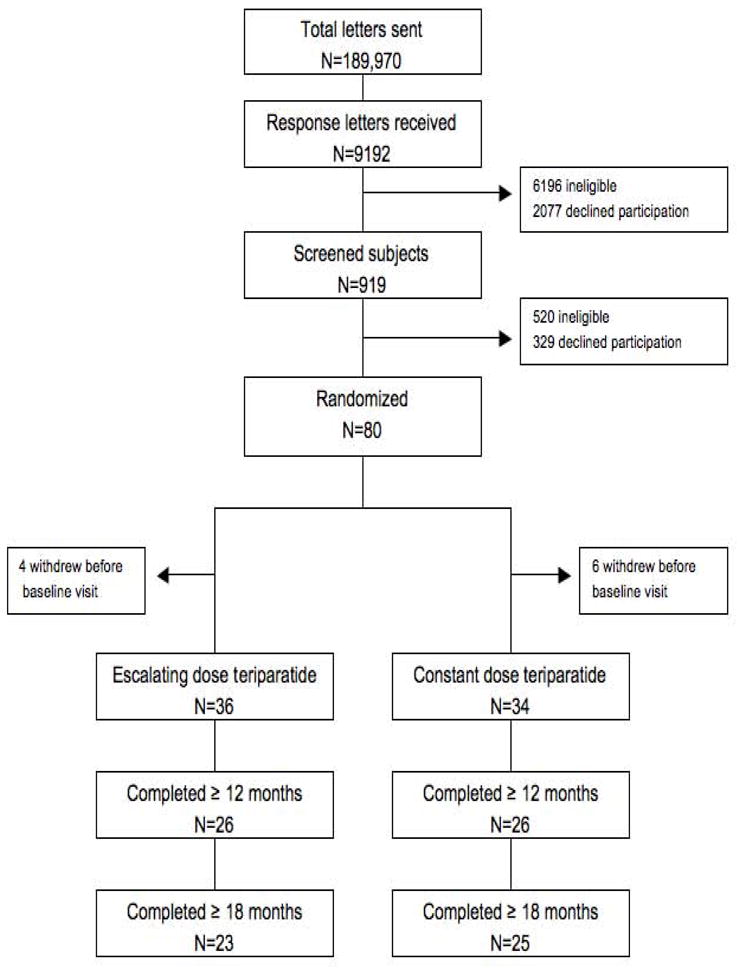

We mailed 189,970 recruitment letters to women within the Greater Boston area (Figure 1). Of 9192 women who returned a preliminary questionnaire, 919 were interested and eligible for further screening. Of these, 319 declined participation and 520 were ineligible based on results of their screening BMD or blood tests. Eighty women were randomized but 10 of them decided not to enroll. The remaining 70 women were included in the study.

Figure 1.

Recruitment and progression through the study protocol.

Participants were required to be postmenopausal women 46 to 85 years old; have a BMD T-score of ≤ −2.0 at the lumbar spine in the posterior-anterior or lateral projection or the femoral neck by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA), or a central vertebral body trabecular BMD T-score of ≤ −2.0 by quantitative computed tomography (QCT); serum calcium level below 10.6 mg/dL; serum creatinine below 2 mg/dL; serum alkaline phosphatase below 150 U/L; serum aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase less than twice the upper limit of the normal range; serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D ≥15 ng/mL; 24 hour urine calcium <400 mg; and normal levels of PTH, TSH, and prolactin. Women were excluded if they had ever taken bisphosphonates or if they had taken glucocorticoids for more than 14 days in the previous year. Women were also excluded if taking other medications known to affect bone metabolism in the previous year, such as selective estrogen receptor modulators, hormone replacement therapy, anti-convulsants, lithium chloride, or suppressive doses of thyroxine, were excluded as were women with a history of bony disorders or nephrolithiasis within the past 5 years.

2.2 Study Protocol

Women were randomized to escalating or constant dose teriparatide for 18 months, after stratification by age (above or below 65) and PA spine BMD (Z-score above or below −2.5). The escalating dose regimen consisted of 20 mcg sc teriparatide once-daily from baseline to month 6 (phase 1), 30 mcg sc once-daily from month 6 to 12 (phase 2), and 40 mcg sc once-daily from month 12 to 18 (phase 3). The constant dose regimen was 30 mcg sc teriparatide once-daily for 18 months.

The teriparatide dose was reduced by 25% if any serum calcium value was above 11.5 mg/dL, if 24-hour urinary calcium excretion exceeded 400 mg/day, or if the investigators felt that the subject was experiencing a side effect of therapy. If hypercalcemia, hypercalciuria or symptoms persisted after two such dose reductions, teriparatide was discontinued. Compliance with study medications was assessed by counting residual medication at each visit.

Blood was collected at baseline, 1.5, 3, 6, 7.5, 9, 12, 13.5, 15, and 18 months to assess complete blood count, routine electrolytes, creatinine, serum C-telopeptide of type 1 collagen (CTX), osteocalcin (OC), and procollagen I N-terminal propeptide (PINP). At each visit, serum calcium was measured before and 4 to 6 hours after teriparatide injection. Twenty-four hour urinary calcium excretion was measured at baseline, 1.5, 7.5, and 13.5 months. BMD was measured by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry at baseline and every 6 months. Trabecular BMD of the lumbar spine was measured by quantitative computed tomography at baseline and at 18 months. Cyclic AMP/creatinine was measured in urine collected during the 2 hours immediately preceding and the 2 hours immediately following that day’s teriparatide administration at baseline, month 9, and month 18 in 9 women in the constant dose group. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Massachusetts General Hospital and all women provided written informed consent.

2.3 Teriparatide preparation

Our hospital’s manufacturing pharmacy dissolved pyrogen-free synthetic teriparatide (good manufacturing practices-grade human PTH (1–34), Bachem, Inc., Torrance, CA) at a concentration of 100 mcg/ml in 0.9% pharmaceutical-grade NaCl, 0.1M pharmaceutical-grade Na acetate, adjusted the pH to 5.0, sterilized the solution by membrane filtration, and froze it at −70° C. until dispensed to patients, who froze it until first use and refrigerated it thereafter until final use within 7 days. Its purity, stability, and concentration after pharmacy and/or home storage were verified by shallow-gradient reverse-phase high-pressure liquid chromatography.

2.4 Measurements of Bone Mineral Density

BMD of the lumbar spine in the posterior-anterior and lateral projections, the proximal femur, the distal one-third radius shaft, and total body were measured by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (QDR 4500A, Hologic Inc., Waltham, MA). For the radius shaft, 2 measurements were made at each visit and their mean was utilized in all analyses. The standard deviations for our short-term in vivo measurements are 0.005 g/cm2 for the posterior-anterior spine, 0.014 g/cm2 for the lateral spine, 0.007 g/cm2 for the femoral neck, and 0.006 g/cm2 for the total hip. Daily measurements of an anthropomorphic spine phantom demonstrated long-term stability of the densitometer. Individual vertebrae with obvious deformities or areas of focal sclerosis were excluded from analyses. Total body scans were analyzed without the head region because it often contains artifacts. All bone density scans were analyzed by individuals blinded to study treatment.

Trabecular bone mineral density of the lumbar spine was determined with the use of quantitative computed tomography (General Electric LightSpeed QXi or LightSpeed Plus scanners, General Electric Healthcare, Waukesha, WI). Axial scans were obtained through the mid-body of the first four lumbar vertebrae. The density of trabecular bone was determined by means of comparison with an internal hydroxyapatite standard, and the values obtained for the vertebrae were then averaged. The precision error for this technique is 3 to 5 mg/cm3.

2.5 Measurements of Bone Turnover and Urinary Cyclic AMP

Serum CTX was measured using an enzyme-linked immunoassay (Nordic Bioscience, Denmark). Serum PINP was measured using a radioimmunoassay (Orion Diagnostica, Espoo, Finland). Serum OC was measured using an enzyme-linked immunoassay (ALPCO Diagnostics, Windham, NH). The intra-assay coefficients of variation for CTX, P1NP, and OC are 5.2–6.8%, 3.5–5.5%, and 5.6%, respectively, in our laboratory. Urinary cAMP was measured using a competitive radioimmunoassay which in our laboratory has an intra-assay variability of 6.2%. All bone marker samples and all urine cyclic AMP and creatinine measurements for each subject were batched and measured together in the same assay, and each assay contained samples from each treatment group.

2.6 Statistical Analysis

Because this was a physiologic study evaluating the impact of stepwise increases in teriparatide, per protocol analysis was performed as was pre-specified in our analysis plan. Outcomes data were analyzed in women who remained on teriparatide throughout the first stepwise increase (i.e. until month 12 or later). Of the 70 women who enrolled, 11 dropped out during the first 6 months, and 7 dropped out during the next 6 months. The remaining 52 women were included in the primary analysis. Four women withdrew between months 12 and 18; their data until teriparatide discontinuation are included in all analyses.

Baseline characteristics of the study groups were compared by independent samples t-tests or Wilcoxon Rank Sum tests. The pre-specified primary end point was difference in the area under the curve (AUC) in bone turnover markers (OC, PINP, and CTX) between the two treatment regimens. AUC was calculated for each woman using the trapezoidal rule after subtracting out her pre-treatment baseline value (i.e. net AUC). The mean net AUCs of the two treatment groups were then compared using independent samples t-tests. Paired t-tests were used to analyze within-group change in bone mineral density and urinary cAMP/creatinine between months 0 and 18. Pearson’s correlation was performed to assess the association between changes in P1NP, OC, or CTX and changes in BMD within each 6-month phase. In addition, longitudinal mixed models ANOVA with random individual subject intercepts, fixed time and treatment main effects, and fixed time × treatment interaction was applied to estimate the within-treatment-group mean changes of the bone density parameters and the bone markers over time and to compare the longitudinal mean change patterns between the treatment groups. Because the longitudinal common pattern of the bone markers over the entire observation period was parabolic, the time dependency pattern was modeled by introducing a quadratic time term. A simplified “phase” analysis was also conducted in which linear responses were fit separately for each 6 month phase of the trial (i.e., 0–6 months, 6–12 months and 12–18 months) and the slopes of the two treatment groups were directly compared within each of these three 6-month intervals. For this phase analysis, Bonferroni correction was applied such that a p-value < 0.017 was considered statistically significant. For all other analyses, a p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The data analysis was carried out by using SAS version 9.2. Data are expressed as the mean ± SD unless otherwise specified.

3. Results

3.1 Baseline Subject Characteristics

Table 1 summarizes the demographics and baseline clinical characteristics of the individual groups. The women ranged from 47 to 83 years old. There were no significant differences between the groups in any measured parameter. The baseline characteristics were also similar among women who dropped out of the study (data not shown).

Table 1.

Baseline subject characteristics

| Escalating dose n=26 | Constant dose n=26 | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 62.2 ± 8.8 | 62.7 ± 7.2 | 0.53 |

| Height (cm) | 161.9 ± 7.4 | 162.7 ± 6.2 | 0.67 |

| Weight (kg) | 64.6 ± 10.7 | 62.2 ± 7.9 | 0.34 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 24.7 ± 3.6 | 23.6 ± 3.2 | 0.29 |

| Serum calcium (mg/dl) | 9.5 ± 0.3 | 9.4 ± 0.4 | 0.15 |

| 24 hour urine calcium/urine creatinine | 0.19 ± 0.10 | 025 ±0.11 | 0.08 |

| PTH (pg/ml) | 42 ± 11 | 36 ± 10 | 0.06 |

| 25-Hydroxyvitamin D (ng/ml)* | 29 ± 9 | 30 ± 13 | 0.75 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (U/liter) | 83 ± 17 | 75 ± 17 | 0.06 |

| Osteocalcin (ng/ml) | 18 ± 6 | 16± 6 | 0.26 |

| P1NP (ng/ml) | 57 ± 20 | 51 ± 20 | 0.29 |

| CTX (ng/ml) | 0.45 ± 0.20 | 0.46 ± 0.31 | 0.91 |

| DXA BMD (g/cm2) | |||

| Posterior-anterior spine | 0.825 ± 0.109 | 0.841 ± 0.075 | 0.54 |

| Lateral spine | 0.623 ± 0.068 | 0.628 ± 0.041 | 0.78 |

| Femoral neck | 0.647 ± 0.069 | 0.624 ± 0.061 | 0.22 |

| Total hip | 0.759 ± 0.085 | 0.768 ± 0.079 | 0.68 |

| 1/3 Radius | 0.624 ± 0.095 | 0.627 ± 0.053 | 0.84 |

| DXA total body bone mineral content (g) | 1326 ± 188 | 1362 ± 210 | 0.52 |

| QCT trabecular spine BMD (g/cm3) | 85 ± 22 | 79 ± 19 | 0.29 |

Values am the mean +/−SD

The last column shows the p values determined by t-test or Wilcoxon rank sum to convert to nanomoles per liter, multiply by 2.496

3.2 Teriparatide Compliance and Dosing

All but 4 women (2 per treatment group) took at least 90 percent of their prescribed teriparatide doses. Seven women in the constant dose group and 9 women in the escalating dose group had protocol-mandated dose reductions. After taking into account medication compliance and protocol-mandated dose changes, the actual mean teriparatide doses during study months 0–6, 6–12, and 12–18, were 29, 27, and 27 mcg/day in the constant dose group and 20, 29, and 37 mcg/day in the ascending dose group.

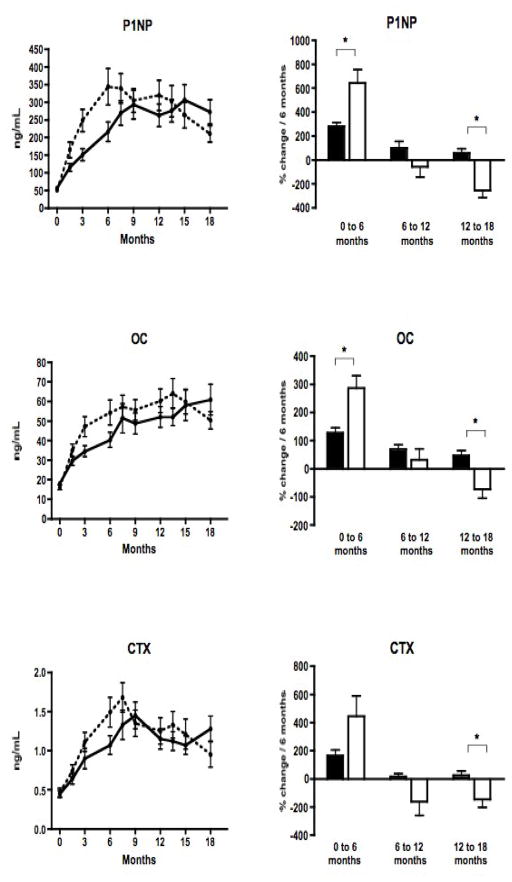

3.3 Changes in Bone Turnover Markers

Mean values of serum OC, PINP, and CTX levels during the 18 month study period are shown in Figure 2, and differed between groups over the course of the entire study (p<0.001 for each marker). Longitudinal analysis indicated that the escalating dose prevented the late decline in bone markers. However, bone marker responses also differed during the initial phase of the study. During phase 1, when the teriparatide dose was higher in the constant dose group (30 mcg/day) than in the escalating dose group (20 mcg/day), mean bone marker levels rose faster on the higher dose (p=0.014 for OC; p=0.015 for P1NP; and p=0.038 for CTX). During phase 2, when both groups were receiving equivalent teriparatide doses, mean levels of all markers were relatively stable and temporal patterns of bone markers did not differ between groups. During phase 3, when the teriparatide dose was higher in the escalating dose group (40 mcg/day) than in the constant dose group (30 mcg/day), dose escalation prevented the late decline in bone markers: mean OC, PINP, and CTX levels declined in the constant dose group, but plateaued or increased slightly in the escalating dose group (p<0.001 for OC and P1NP; and p=0.004 for CTX). These early and late differences between dose regimens cancelled out, and mean AUC (our primary study endpoint) did not differ between regimens for any bone marker.

Figure 2.

In the left column, mean (± SE) serum PINP, OC, and CTX levels in the escalating dose (solid line) and constant dose (dashed line) teriparatide groups over the 18-month study. In the right column, mean % change per 6 month time period (± SE) in serum P1NP, OC, and CTX levels in the escalating dose (black bar) and constant dose (open bar) teriparatide groups. In the first 6 months, there was a greater increase in P1NP and OC in the constant dose group than in the escalating dose group. In the last 6 months, bone markers declined with a negative rate of change in the constant dose group, and remained steady or increased in the escalating dose group. (* indicates p<0.017)

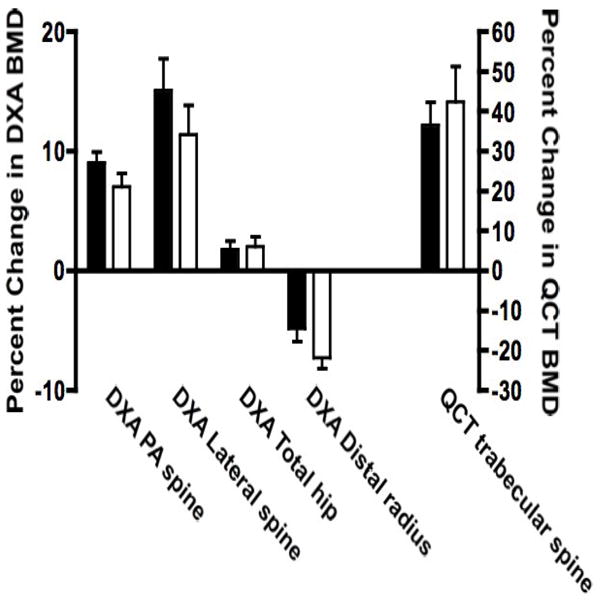

3.4 Changes in Bone Mineral Density

DXA BMD of the lumbar spine and total hip increased significantly and radial BMD decreased significantly in both groups (escalating dose vs. constant dose; PA spine: 9.0 ± 4.3% vs. 7.0 ± 5.5%; Total hip: 1.8 ± 3.3% vs. 2.0 ± 4.1%; Distal radius: −4.8 ± 5.1% vs. −7.3 ± 4.6%; within-group p<0.05 for all sites). Neither total body bone mineral content (BMC) nor total body BMD changed significantly in either group (data not shown). Vertebral trabecular bone density as assessed by QCT increased dramatically in both groups (36 ± 27% vs. 42 ± 44%; within-group p<0.01). However the changes in DXA BMD and QCT BMD did not differ significantly between the two treatment groups at any skeletal site (Figure 3). Further analysis did not reveal consistent differences between treatment groups within any 6-month phase of the study (data not shown). There were no consistent correlations between change in bone resorption and formation markers and change in BMD during any 6-month phase (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Mean (± SE) percent change in bone mineral density by DXA of the posterior-anterior spine, lateral spine, total hip, femoral neck, distal radius and total body and by QCT of the trabecular lumbar spine in the escalating dose (solid bar) and constant dose (open bar) teriparatide groups. Note that the scale for QCT BMD is different and is marked on the rightward y-axis. There were no significant differences between the two treatment groups at any skeletal site.

3.5 Changes in Serum Calcium

Eight women were withdrawn due to hypercalcemia despite dose reductions during phase 1 and phase 2 (5 in the escalating dose group, 3 in the constant dose group); no women were withdrawn due to hypercalcemia during phase 3. The average increase in serum calcium 4 hours after teriparatide administration differed between the two groups throughout the study, with greater increases in the constant dose group at the end of Phase 1 (0.88 ± 0.46 mg/dL vs. 0.52 ± 0.34 mg/dL, p<0.01) and greater increases in the escalating dose group at the end of phase 3 (0.88 ± 0.46 mg/dL vs 0.56 ± 0.44 mg/dL, p=0.02). These longitudinal inter-group differences in calcemic response parallel the longitudinal inter-group differences in bone marker responses and concurrent teriparatide doses.

3.6 Changes in Urinary cAMP

The baseline characteristics and change in bone turnover markers of the 9 women in the cAMP substudy were similar to those of the entire constant-dose group (data not shown). Theincrease in urinary cAMP/creatinine excretion during the 2 hours immediately after teriparatide administration did not significantly differ throughout the study: 3.9 ± 2.4 fold increase at month 0, 3.1 ± 1.2 fold increase at month 9, and 4.6 ± 3.6 fold increase at month 18.

4. Discussion

Teriparatide currently is the only FDA-approved anabolic agent for osteoporosis in the U.S. Although teriparatide increases bone mass more than do anti-resorptive medications, the response to daily teriparatide therapy dissipates over time. Our objective was to determine whether increasing the teriparatide dose in a step-wise fashion could prevent the decline in bone formation markers that occurs during prolonged teriparatide administration. We found that the teriparatide induced increases in bone formation and bone resorption markers did not wane during months 12–18 in the escalating dose group. Despite this, teriparatide-induced increases in QCT and DXA BMD were similar in the escalating and constant dose teriparatide regimens over the 18 month study period.

Several other strategies have been tested to try to increase the anabolic effects of teriparatide on bone. It was initially hoped that co-administration of teriparatide with an anti-resorptive agent might yield synergistic results by selectively inhibiting teriparatide-induced increases in bone resorption. Surprisingly, combining teriparatide with alendronate attenuated teriparatide-induced increases in both bone resorption and bone formation and failed to produce synergistic effects on BMD. For example, while addition of bisphosphonates to PTH increased total hip BMD slightly more than did PTH monotherapy at 1 year, by 2 years lumbar spine, total hip, and femoral neck BMD were significantly higher in both women and men who received teriparatide monotherapy. Similarly, combining teriparatide with raloxifene for 18 months was no more effective than teriparatide monotherapy in women previously treated with raloxifene. Another study administered teriparatide cyclically (alternating 3 months on/off treatment) in the hopes of capitalizing on the theoretical “anabolic window” of bone formation that has been suggested to occur in the initial months of teriparatide use. However cyclic teriparatide administration was no more effective at increasing BMD than was daily teriparatide therapy. Finally, teriparatide retreatment after a prolonged treatment-free interval was investigated as a strategy to restore the initial exuberant anabolic response to teriparatide. Surprisingly, after a 1-year “drug holiday”, BMD and bone formation marker responses to teriparatide remained markedly attenuated. Thus, though seemingly logical strategies to overcome the gradual decline in the skeletal response to teriparatide or PTH have been tried, none has been successful.

Our strategy of escalating the dose of teriparatide did not improve the primary outcome measure, the AUCs of serum bone markers, as compared with the constant dose regimen. There were, however, significant differences in the rate and direction of change between the treatment groups during the last 6 months of the study. In the constant dosing arm, PINP, OC, and CTX increased during the first 6 to 12 months of teriparatide administration after which levels began to decline as has been reported in many prior studies. In contrast, in the escalating dose teriparatide group, levels of PINP, OC, and CTX remained steady or even continued to increase after 6 to 12 months of teriparatide delivery. The calcemic response to teriparatide was similar to that of the bone markers in each group. These findings suggest that escalating the dose of teriparatide overcomes biochemical skeletal resistance to some degree. However, maintenance of skeletal responses for this short interval did not produce greater improvements in BMD in women who received the escalating teriparatide dose regimen over 18 months. It is also possible that the decline in bone marker response was merely delayed in the escalating dose group. A longer trial would be required to determine the full extent of changes in the pattern of bone marker response. Because, however, increases in BMD often lag behind changes in bone turnover markers in people treated with teriparatide, it is possible we did not see differences in BMD response because the treatment period was not sufficiently long. Alternatively, it may be that changes in indices of bone formation and resorption are dissociated from BMD response to teriparatide.

Although the mechanism(s) of the anabolic response to teriparatide are partly understood, the physiologic mechanisms underlying the waning response to teriparatide after 6–12 months daily therapy are totally unknown. While the development of antibodies to the injected teriparatide could explain this phenomenon (by interfering with peptide binding to the parathyroid hormone receptor, or prolonging residence of the peptide in blood), we have not been able to detect teriparatide-binding antibodies in the blood of patients treated with teriparatide for 2–3 years. Other possible explanations include downregulation of PTH receptors, depletion of teriparatide target cells (e.g. osteoblasts, osteoblast precursors, bone lining cells), alterations in biochemical signaling downstream of the PTH receptor, or changes in teriparatide pharmacokinetics (absorption or metabolism). Our finding that escalating teriparatide can maintain bone formation marker levels at or near peak is consistent with any of these potential mechanisms. Further research is necessary to determine why the response to teriparatide wanes with time, and may also provide insights into the cellular physiology of once-daily PTH therapy.

Although the time course of skeletal responses to teriparatide have been described previously, long-term effects on renal responses have not been examined. In contrast to the decline in the skeletal response that occurred after 6 to 12 months in women taking the constant once-daily dose of teriparatide, their acute renal response to teriparatide, as assessed by urine cAMP excretion, did not change during 18 months of teriparatide administration. Because of the small numbers of people studied, however, these findings should be interpreted cautiously until verified in more women. In addition, our results cannot exclude the possibility that downregulation of the renal response to PTH occurs downstream of the cAMP response, or via pathways independent of cAMP. If confirmed in future studies, our results would suggest that the mechanism leading to waning skeletal response to teriparatide is bone-specific, and thus argues against time-dependent changes in teriparatide pharmacokinetics. As we observed that serum calcium response to teriparatide wanes over time, this would also imply that the acute calcemic response to teriparatide is primarily due to its skeletal effects, not its renal effects.

Certain limitations of this study should be noted. The study employed average doses of teriparatide higher than the FDA-approved dose of 20 mcg/day. This design was necessary to ensure that the cumulative teriparatide exposure of both dosing groups was equivalent. Previous studies involving 20 mcg/day have demonstrated a similar attenuated response to teriparatide over time. The dropout rate was higher than expected (10 women in escalating dose group, 8 women in constant dose group), but baseline characteristics of the women who dropped out were similar to those who completed the study. The patterns of bone marker response differed between groups in the last 6 months of our study period. It is possible that this terminal difference between the two dosing regimens would alter BMD or bone structural responses to teriparatide over a longer interval.

In summary, stepwise increases in teriparatide prevented the decline in bone turnover markers that is observed with chronic administration. BMD increases, however, were similar to the constant dose regimen. Despite the waning of bone marker levels in the constant dose regimen, renal cyclic-AMP responsiveness to sc teriparatide was maintained throughout the study. These data provide new insights into the chronic effects of once-daily teriparatide administration. Further research into mechanisms of the time-dependent decline in skeletal response are needed to help understand the anabolic actions of teriparatide therapy.

Research Highlights.

Once-daily injections of teriparatide (PTH 1–34) initially increase biochemical markers of bone formation and resorption, but markers peak after 6–12 months and then decline despite continued treatment.

We randomized 52 postmenopausal women with osteoporosis to either a constant or an escalating subcutaneous teriparatide dose for 18 months.

Stepwise increases in teriparatide prevented the decline in bone turnover markers that is observed with chronic administration.

Nonetheless, bone density increases were equivalent to a constant dose teriparatide regimen.

Acute renal response to teriparatide did not change over 18 months of teriparatide administration, suggesting that the time-dependent waning of the response to teriparatide is bone-specific.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Robbin Cleary, Sarah Zhang, and Bijoy Thomas for bone density measurements; and the nursing and dietary staff of the Mallinckrodt General Clinical Research Center for their dedicated care of the study participants.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants 5 P50 AR44855, K24 DK02759, 1 UL1 RR025758-03, and RR-1066.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: Robert Neer has consulted for Eli Lilly, and Joel Finkelstein has consulted for Merck. All other authors have no conflicts of interest.

Clinical Trial Registration #: NCT00086619

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Elaine W. Yu, Email: ewyu@partners.org.

Robert M. Neer, Email: rneer@partners.org.

Hang Lee, Email: hlee5@partners.org.

Jason J. Wyland, Email: jwyland@partners.org.

Amanda V. de la Paz, Email: amandadelapaz@gmail.com.

Melissa C. Davis, Email: davismelissac@gmail.com.

Makoto Okazaki, Email: okazakiMKT@chugai-pharm.co.jp.

Joel S. Finkelstein, Email: jfinkelstein@partners.org.

References

- 1.Finkelstein JS. Osteoporosis. 21. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Company; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Black DM, Cummings SR, Karpf DB, Cauley JA, Thompson DE, Nevitt MC, Bauer DC, Genant HK, Haskell WL, Marcus R, Ott SM, Torner JC, Quandt SA, Reiss TF, Ensrud KE. Randomised trial of effect of alendronate on risk of fracture in women with existing vertebral fractures. Fracture Intervention Trial Research Group. Lancet. 1996;348:1535–41. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)07088-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harris ST, Watts NB, Genant HK, McKeever CD, Hangartner T, Keller M, Chesnut CH, 3rd, Brown J, Eriksen EF, Hoseyni MS, Axelrod DW, Miller PD. Effects of risedronate treatment on vertebral and nonvertebral fractures in women with postmenopausal osteoporosis: a randomized controlled trial. Vertebral Efficacy With Risedronate Therapy (VERT) Study Group. Jama. 1999;282:1344–52. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.14.1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Neer RM, Arnaud CD, Zanchetta JR, Prince R, Gaich GA, Reginster JY, Hodsman AB, Eriksen EF, Ish-Shalom S, Genant HK, Wang O, Mitlak BH. Effect of parathyroid hormone (1–34) on fractures and bone mineral density in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1434–41. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200105103441904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Finkelstein JS, Klibanski A, Schaefer EH, Hornstein MD, Schiff I, Neer RM. Parathyroid hormone for the prevention of bone loss induced by estrogen deficiency. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:1618–23. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199412153312404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Body JJ, Gaich GA, Scheele WH, Kulkarni PM, Miller PD, Peretz A, Dore RK, Correa-Rotter R, Papaioannou A, Cumming DC, Hodsman AB. A randomized double-blind trial to compare the efficacy of teriparatide [recombinant human parathyroid hormone (1–34)] with alendronate in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:4528–35. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-020334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lindsay R, Nieves J, Formica C, Henneman E, Woelfert L, Shen V, Dempster D, Cosman F. Randomised controlled study of effect of parathyroid hormone on vertebral-bone mass and fracture incidence among postmenopausal women on oestrogen with osteoporosis. Lancet. 1997;350:550–5. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)02342-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kurland ES, Cosman F, Mcmahon DJ, Rosen CJ, Lindsay R, Bilezikian J. Parathyroid Hormone as a Therapy for Idiopathic Osteoporosis in Men: Effects on Bone Mineral Density and Bone Markers. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2000;85:3069. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.9.6818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Orwoll ES, Scheele WH, Paul S, Adami S, Syversen U, Diez-Perez A, Kaufman JM, Clancy AD, Gaich GA. The effect of teriparatide [human parathyroid hormone (1–34)] therapy on bone density in men with osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res. 2003;18:9–17. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2003.18.1.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Finkelstein J, Hayes A, Hunzelman JL, Wyland JJ, Lee H, Neer RM. The effects of parathyroid hormone, alendronate, or both in men with osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1216–26. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa035725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Finkelstein J, Leder BZ, Burnett SM, Wyland JJ, Lee H, de la Paz AV, Gibson K, Neer RM. Effects of teriparatide, alendronate, or both on bone turnover in osteoporotic men. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2006;91:2882–7. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-0190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McClung MR, San Martin J, Miller PD, Civitelli R, Bandeira F, Omizo M, Donley DW, Dalsky GP, Eriksen EF. Opposite bone remodeling effects of teriparatide and alendronate in increasing bone mass. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:1762–8. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.15.1762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cosman F, Wermers R, Recknor C, Mauck K, Xie L, Glass E, Krege J. Effects of Teriparatide in Postmenopausal Women with Osteoporosis on Prior Alendronate or Raloxifene: Differences between Stopping and Continuing the Antiresorptive Agent. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2009;94:3772. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-2719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Finkelstein JS, Klibanski A, Arnold AL, Toth TL, Hornstein MD, Neer RM. Prevention of estrogen deficiency-related bone loss with human parathyroid hormone-(1–34): a randomized controlled trial. Jama. 1998;280:1067–73. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.12.1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen P, Satterwhite JH, Licata AA, Lewiecki EM, Sipos AA, Misurski DM, Wagman RB. Early changes in biochemical markers of bone formation predict BMD response to teriparatide in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20:962–70. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.050105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cosman F, Nieves J, Zion M, Woelfert L, Luckey M, Lindsay R. Daily and cyclic parathyroid hormone in women receiving alendronate. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:566–75. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ettinger B, San Martin J, Crans G, Pavo I. Differential effects of teriparatide on BMD after treatment with raloxifene or alendronate. J Bone Miner Res. 2004;19:745–51. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.040117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hodsman A, Fraher L, Watson P, Ostbye T, Stitt L, Adachi J, Taves D, Drost D. A Randomized Controlled Trial to Compare the Efficacy of Cyclical Parathyroid Hormone Versus Cyclical Parathyroid Hormone and Sequential Calcitonin to Improve Bone Mass in Postmenopausal Women with Osteoporosis. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 1997;82:620. doi: 10.1210/jcem.82.2.3762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lane NE, Sanchez S, Genant HK, Jenkins DK, Arnaud CD. Short-term increases in bone turnover markers predict parathyroid hormone-induced spinal bone mineral density gains in postmenopausal women with glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. Osteoporosis international. 2000;11:434–42. doi: 10.1007/s001980070111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hodsman AB, Hanley DA, Ettinger MP, Bolognese M, Fox J, Metcalfe AJ, Lindsay R. Efficacy and safety of human parathyroid hormone-(1–84) in increasing bone mineral density in postmenopausal osteoporosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:5212–20. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-030768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Greenspan SL, Bone HG, Ettinger MP, Hanley DA, Lindsay R, Zanchetta JR, Blosch CM, Mathisen AL, Morris SA, Marriott TB Group* FTTOOWPHS. Effect of Recombinant Human Parathyroid Hormone (1–84) on Vertebral Fracture and Bone Mineral Density in Postmenopausal Women with Osteoporosis: A Randomized Trial. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:326. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-5-200703060-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Black DM, Bouxsein ML, Palermo L, Mcgowan JA, Newitt DC, Rosen E, Majumdar S, Rosen CJ. Randomized Trial of Once-Weekly Parathyroid Hormone (1–84) on Bone Mineral Density and Remodeling. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2008;93:2166. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-2781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mitlak BH, Burdette-Miller P, Schoenfeld D, Neer RM. Sequential effects of chronic human PTH (1–84) treatment of estrogen-deficiency osteopenia in the rat. J Bone Miner Res. 1996;11:430–9. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650110403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bauer D, Garnero P, Bilezikian J, Greenspan S, Ensrud K, Rosen C, Palermo L, Black D. Short-Term Changes in Bone Turnover Markers and Bone Mineral Density Response to Parathyroid Hormone in Postmenopausal Women with Osteoporosis. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2006;91:1370. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-1712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Finkelstein JS, Wyland JJ, Leder BZ, Burnett-Bowie S-AM, Lee H, Jüppner H, Neer RM. Effects of teriparatide retreatment in osteoporotic men and women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:2495–501. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-0154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Finkelstein JS, Hayes A, Hunzelman JL, Wyland JJ, Lee H, Neer RM. The effects of parathyroid hormone, alendronate, or both in men with osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1216–26. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa035725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Obermayer-Pietsch BM, Marin F, McCloskey EV, Hadji P, Farrerons J, Boonen S, Audran M, Barker C, Anastasilakis AD, Fraser WD, Nickelsen T, Investigators E. Effects of two years of daily teriparatide treatment on BMD in postmenopausal women with severe osteoporosis with and without prior antiresorptive treatment. J Bone Miner Res. 2008;23:1591–600. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.080506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saag KG, Shane E, Boonen S, Marin F, Donley DW, Taylor KA, Dalsky GP, Marcus R. Teriparatide or Alendronate in Glucocorticoid-Induced Osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2028. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa071408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Finkelstein JS, Wyland JJ, Lee H, Neer RM. Effects of Teriparatide, Alendronate, or Both in Women with Postmenopausal Osteoporosis. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2010;95:1838–1845. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-1703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Taylor A, Konrad PT, Norman ME, Harcke HT. Total body bone mineral density in young children: influence of head bone mineral density. J Bone Miner Res. 1997;12:652–5. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1997.12.4.652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rosenthal DI, Ganott MA, Wyshak G, Slovik DM, Doppelt SH, Neer RM. Quantitative computed tomography for spinal density measurement. Factors affecting precision. Invest Radiol. 1985;20:306–10. doi: 10.1097/00004424-198505000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Okazaki M, Ferrandon S, Vilardaga JP, Bouxsein ML, Potts JT, Jr, Gardella TJ. Prolonged signaling at the parathyroid hormone receptor by peptide ligands targeted to a specific receptor conformation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:16525–30. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808750105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Black D, Greenspan SL, Ensrud K, Palermo L, McGowan JA, Lang TF, Garnero P, Bouxsein M, Bilezikian JP, Rosen CJ, Investigators PS. The effects of parathyroid hormone and alendronate alone or in combination in postmenopausal osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1207–15. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa031975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goltzman D. Studies on the mechanisms of the skeletal anabolic action of endogenous and exogenous parathyroid hormone. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2008;473:218–24. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jilka RL. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of the anabolic effect of intermittent PTH. Bone. 2007;40:1434–46. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2007.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]