Clinical Scenario

A 52-year-old man is referred to your gastroenterology practice for a history of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). The patient reports a long history of heartburn symptoms, dating back at least 5 years. His symptoms were responsive to over the counter remedies including antacid tablets and liquids, but eventually became such a regular occurrence that he sought medical care from his primary care physician. He was initially prescribed an H2 blocker, which was incompletely effective, so he was started on proton pump inhibitor therapy. He currently takes 20mg of omeprazole daily which is effective, but notes that if he misses a dose, he sometimes experiences heartburn. He denies dysphagia, nausea or vomiting, blood in his stool, or unintentional weight loss. He has no other chronic medical conditions and takes no other medications. He is a nonsmoker who drinks alcohol in moderation, and has no family history of gastrointestinal cancer. Paperwork from the referring physician states that the reason for consultation is: “screening for Barrett’s esophagus.”

The Problem

In the United States, GERD is a frequent disorder, affecting 10–20% of the population on a regular basis.1 Barrett’s esophagus (BE) is a metaplastic change of the normal esophageal mucosa, in which the normal squamous epithelium of the esophagus is transformed into columnar epithelium with goblet cells in response to chronic inflammation from reflux of acidic gastric contents. Barrett’s esophagus is significantly less common than GERD in the general population, occurring in roughly 1–2 out of 100 persons in the US.2, 3 However, BE is quite common amongst GERD sufferers, occurring in 6 – 18% of cases.2, 4, 5 It is important to note that Barrett’s epithelium is not necessarily associated with symptoms, and its effect on overall mortality is unclear, and may be negligible.6–8 Therefore, BE is of interest because it is considered a pre-malignant condition. Pathologically, BE can progress to dysplasia of the esophageal mucosa and subsequently, to the development of invasive adenocarcinoma.9–11 In epidemiologic studies, BE is associated with a substantially increased risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC), at least 40-fold higher than the general population.12, 13 Current estimates place the risk of EAC among patients with BE between 0.5 and 1% per patient per year.14 Gastroesophageal reflux disease is also highly associated with esophageal adenocarcinoma, as has been shown by several case control studies.15–17 Such studies also consistently show higher odds of esophageal cancer depending on duration and frequency of symptoms. Though the absolute risk of esophageal cancer in persons with GERD cannot be directly measured by such studies, it is undoubtedly quite low given the low incidence of esophageal cancer and the high prevalence of GERD.18

Adenocarcinoma of the esophagus is a relatively rare condition, with <10,000 cases per year in the US.19 However, EAC is on the rise, with several population-based cohort studies demonstrating a 300–500% increase in incidence since the 1970s.20, 21 The reason for this increased frequency of EAC is uncertain, but may be due to increased rates of obesity.22 Rates of esophageal cancer are highest among white men, while women and African Americans have lower rates.21 African Americans have significantly higher esophageal cancer mortality than whites, however.23 Esophageal adenocarcinoma is amongst the most lethal cancers, with an overall 5 year survival of 17%.24 Most esophageal cancers are diagnosed at an advanced stage, when local resection is not possible.19 The primary surgical treatment of advanced esophageal cancer is esophagectomy, which is associated with substantial morbidity and some decrement in quality of life.25, 26

Despite the fact that EAC is an uncommon cancer, a targeted screening approach is of interest because of the morbidity and mortality associated with this disease. Given the widespread use of upper endoscopy to manage GERD, large numbers of subjects with BE are likely to continue to be discovered serendipitously. The question, therefore, is whether a screening endoscopic examination in persons with GERD specifically to detect BE or EAC is a worthwhile pursuit, and whether this approach would lead to decreased burden of esophageal adenocarcinoma.

Management Strategies and Supporting Evidence

Controversy abounds over the issue of BE screening, particularly in regards to which patients should be screened, or if gastroenterologists should screen anyone at all. Screening for BE is typically performed via esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) with biopsies of the esophagus if and when characteristic Barrett’s-type mucosa is seen. Barrett’s esophagus is diagnosed when these biopsies contain intestinal metaplasia. The rational for such screening is that BE is a major risk factor for development of EAC, and that early detection may lead to improved survival. The initial enthusiasm of screening and surveillance programs for BE may have been in part fueled by early reports of cancer risk in BE. These reports might have overestimated the true cancer risk by 50% or more, due to publication bias.27 Also, studies subject to length and lead time bias claimed early detection led to a survival benefit.28, 29 Over the past two decades, as understanding of the natural history of BE and EAC has evolved, several schools of thought have arisen with respect to screening, including (1) screening all patients with GERD; (2) screening patients with specific clinical characteristics; and (3) no screening at all.

Screening all patients with GERD symptoms is one option for detecting BE, but would represent an enormous challenge to medical resources and endoscopists’ time. Current estimates are that approximately 20 – 40% of the U.S. population suffers from heartburn on a weekly or monthly basis.30,1 In some BE patients, esophageal acid exposure manifests with the classical symptoms of heartburn and acid reflux. However, many patients with longstanding acid exposure may have no symptoms at all. Such patients would presumably be missed by a strategy which focused endoscopic screening on those with GERD symptoms. Several prospective studies have demonstrated that a substantial proportion of incident BE occurs in persons without typical reflux symptoms (Table 1).3, 31–35 Thus, while patients with symptomatic heartburn may have a slightly increased incidence of BE, screening on the basis on GERD alone may miss more subjects with BE than it finds. Further evidence regarding the insensitivity of GERD symptoms as a criterion for entry into endoscopic screening programs comes from case-control studies demonstrating that up to half of subjects who develop adenocarcinoma of the esophagus do not have chronic GERD symptoms.15–17

Table 1.

Prospective studies comparing prevalence of BE in GERD and non-GERD patients demonstrating substantial prevalence of BE in subjects who do not have typical GERD symptoms.

| Study | Year | Prevalence of BE in GERD patients (%) | Prevalence of BE in non-GERD patients (%) | Prevalence of BE in the overall study cohort (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| † Gerson et al.33 | 2002 | n/a | 25 | 25 |

| Rex et al.31 | 2003 | 8 | 6 | 7 |

| Ronkainen et al.3 | 2005 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Ward et al.34 | 2006 | 20 | 15 | 17 |

| Zagari et al.35 | 2008 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| * Gerson et al.32 | 2009 | n/a | 6 | 6 |

Asymptomatic women only

Asymptomatic veterans only

In light of the limitations of screening all patients with GERD for BE, other strategies have been proposed in support of screening GERD patients with certain symptoms or clinical characteristics. BE has been found to occur more often in Caucasian males over the age of 50 with longstanding GERD symptoms.17 Inadomi et al. have shown cost effectiveness for one time screening of such patients.36 This screening strategy is only cost effective, however, if only those patients with BE and dysplasia undergo endoscopic surveillance. Furthermore, even using such patient characteristics to focus screening, the number of subjects necessary to screen to detect one cancer remains prohibitively high.37

A primary question, then, is whether we should screen for BE at all. It should be noted that the case of screening for BE or EAC lacks many of the characteristics of a useful screening strategy by established criteria.38, 39 As discussed above, the burden of disease, while increasing, remains small, given the enormous pool of at risk subjects. The preclinical phase cannot be adequately identified or targeted as many patients with BE have no GERD symptoms. Finally, and most importantly, screening has not been sufficiently proven to improve outcomes such as mortality from esophageal cancer.39

Areas of Uncertainty

The benefits of screening and surveillance programs remain unclear. Several studies do show a potential benefit from endoscopic screening and surveillance in BE. Subjects who have their cancer diagnosed as part of a screening and surveillance program are less likely to have nodal involvement, and demonstrate a better two year survival than those presenting symptomatically.28, 40 However, such studies showing a benefit from screening and surveillance of patients with BE are largely retrospective and complicated by selection bias, lead time bias and length bias. In fact, a recent nested case-control study performed in the U.S. Veterans’ Affairs system demonstrated that subjects with adenocarcinoma who had had an upper endoscopy in the five years prior to diagnosis did not have significantly different survival than those presenting symptomatically.41

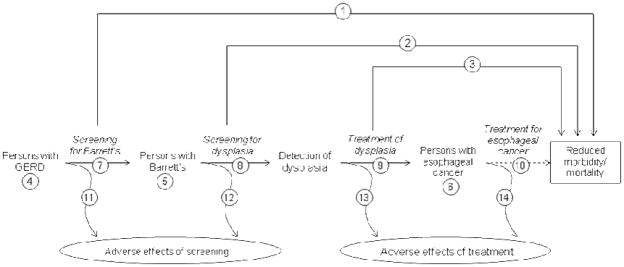

The best evidence to establish the benefit of screening for BE would be a randomized controlled trial of endoscopic screening in GERD patients, measuring the outcome of esophageal cancer mortality. However, such a trial would be cumbersome and costly; given the rarity of esophageal adenocarcinoma and the long latency time between BE and development of cancer, a randomized trial of BE screening in all persons with GERD or in the general population would require large numbers of participants followed for a long period. Therefore, we must rely on indirect evidence that links screening GERD patients with reduced mortality from esophageal cancer. By applying U.S. Preventative Services Task Force guidelines to the decision to perform endoscopy in this setting, one can see the number of unanswered questions to be addressed prior to understanding the utility of such screening and surveillance programs (Figure 1).42

Figure 1.

Important questions in considering whether GERD patients should be screened for Barrett’s esophagus to prevent esophageal adenocarcinoma. Questions labeled with asterisks are either poorly described or currently debated in the medical literature. Based on the US Preventive Health Service Task Force generic framework for screening topics.42

1: Is there direct evidence that screening for Barrett’s esophagus (BE) leads to reduced risk of morbidity or mortality from esophageal cancer?*

2: Is there direct evidence that screening for dysplasia in patients with BE leads to reduced risk of morbidity or mortality from esophageal cancer?*

3: Is there direct evidence that treatment of dysplasia leads to reduced risk of morbidity or mortality from esophageal cancer?

4: What is the prevalence of GERD? What is the prevalence of esophageal cancer in persons with GERD? Can a high risk group be identified?

5: What is the prevalence of BE? What is the prevalence of esophageal cancer in persons with BE? Can a high risk group be identified?

6: What is the prevalence of esophageal cancer? Does all esophageal cancer act the same way? Are there indolent forms of the disease?*

7: Can screening tests accurately identify BE?

8: Can screening tests accurately identify dysplasia?*

9: How effective are treatments for dysplasia? Does treatment of dysplasia reduce the risk of esophageal cancer?

10: How effective is treatment of esophageal cancer? Does treatment improve outcomes for people diagnosed by screening vs. those diagnosed clinically?*

11: What are the adverse effects of screening for BE in people with GERD?*

12: What are the adverse effects of screening for dysplasia in people with BE?*

13: What are the adverse effects of treatment of dysplasia?

14: What are the adverse effects of treatment of esophageal cancer?

Some recommendations for screening and surveillance may show efficacy in study settings but lack effectiveness in the real world. There are standardized techniques for taking biopsies of the esophagus, but clinical practice varies. In both Europe and the United States, professional associations recommend four quadrant biopsies every two centimeters within a segment of suspected BE.43, 44 However, a significant number of endoscopists fail to utilize proper biopsy technique or even identify standardized landmarks during endoscopy for BE.45, 46 In clinical practice, hiatal hernia, inflammation and tortuosity of the esophagus may make accurate technique difficult. Furthermore, biopsy of a normal GE junction may lead to a false positive screen for BE (due to the high prevalence of goblet cells at the normal GE junction in those with chronic GERD symptoms) and biopsies performed in the setting of inflammation may falsely identify dysplasia.47, 48

Once biopsies are obtained, expert pathologic assessment is required to accurately interpret BE specimens. Alikhan et al demonstrated considerable inter-operator variability among community pathologists when interpreting standardized BE pathology.49 High and low grade dysplasia were correctly identified by only 30 and 35% of pathologists, respectively and many incorrectly identified gastric metaplasia as BE. Expert confirmation of BE pathology is only recommended for dysplastic BE and thus misclassified patients may receive inappropriate surveillance.

Additionally, there are costs and risks to screening that are not often factored into the discussion of screening and surveillance programs for BE. These risks become important especially when the disease (esophageal cancer) is rare and the screening population (patients with GERD) is large. Therefore, the potential good done for the very few must outweigh the risks, costs and inconvenience to the many. While uncommon, EGD has risks associated with sedation, perforation, infection and bleeding. These small risks become significant when EGD is applied to millions of people to screen for a rare cancer.18 There may be a risk in labeling patients with BE as well.50 Quality of life is diminished for patients diagnosed with BE and those participating in surveillance programs compared to population norms.51, 52 Many patients overestimate their cancer risk and add psychological stress that is difficult to quantify.53 Finally, patients with BE have increased insurance premiums compared to those without BE.54

Screening for BE with or without subsequent surveillance remains a controversial topic. The current state of technology, available data in the published literature and growing concern over costs in medical care all raise substantial concerns about the utility of such programs. Several potentially disruptive technologies hold the promise of changing this calculus. Ultra-thin trans-nasal endoscopy may allow screening of unsedated patients, greatly lessening the cost of screening, and allowing higher throughput.55 Capsule endoscopy or other novel imaging may also obviate the need for per oral endoscopy for screening.56 Multiple imaging technologies hold the promise to improve our ability to detect dysplasia, perhaps allowing subsequent surveillance intervals to be lengthened or omitted altogether.57–59 Ablative therapies may allow for intervention that would obviate the need for follow-up endoscopy and may change the natural history and downstream costs associated with the lesion.60 All of these possibilities are intriguing, and may change our approach to cancer prevention, but the potential of the interventions in the screening setting remains unproven.

Published Guidelines

There are a number of published guidelines that address the question of BE screening amongst persons with GERD (Table 2). The American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) published a medical position statement on the management of GERD in 2008, which utilized explicit evidentiary methodology.61 The AGA guidelines determined that there was insufficient evidence to recommend for or against routine upper endoscopy in the setting of chronic GERD symptoms to diminish the risk of death from esophageal cancer. The AGA guidelines also determined that there was insufficient evidence to recommend for or against endoscopic screening for BE and dysplasia in adults 50 years or older with greater than 5–10 years of heartburn to reduce mortality from esophageal adenocarcinoma.

Table 2.

Recommendations from published guidelines regarding screening for Barrett’s esophagus

| Society/Organization | Persons in whom endoscopic screening for BE is recommended |

|---|---|

| American Gastroenterological Association | Insufficient evidence |

| American College of Gastroenterology | Insufficient evidence |

| American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy | Screening in high risk groups

|

| British Society of Gastroenterology | Screening not recommended |

| United States Preventive Services Taskforce | No guideline |

GERD: Gastroesophageal reflux disease; BE: Barrett’s esophagus

The American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) also published guidelines addressing the management of GERD and BE in 2005 and 2008 respectively.43, 62 These guidelines also recognize that screening for BE is controversial due to the lack of documented impact on esophageal cancer mortality. Similar to the AGA guidelines, the ACG guidelines report inadequate evidence to recommend routine screening for BE in any specific high-risk population (such as GERD patients or older individuals).

The American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) published guidelines on the role of endoscopy in BE and GERD in 2006 and 2007, respectively.44, 63 The ASGE recommends that screening for BE should be considered “in selected patients with chronic, longstanding GERD.” However, the ASGE does not recommend additional screening following a negative initial screening examination. Endoscopy at the time of presentation with GERD symptoms is also recommended for persons “at risk of Barrett’s esophagus,” including patients with a prolonged history of GERD symptoms (>5 years), white race, male sex, older age (>50), and family history of BE and/or adenocarcinoma of the esophagus. However, the ASGE graded this recommendation 2C, indicating a very weak recommendation with unclear benefit.

The British Society of Gastroenterology guidelines state that endoscopic screening of patients suffering from heartburn in order to detect BE is not recommended.64 The United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) does not currently have any published guidelines addressing screening for esophageal cancer.

There is perhaps no area in gastroenterology where the clinical practice is more at odds with the published data and guidelines than in endoscopic screening for BE. Although, as noted above, guidelines are either unsupportive or equivocal on such practices, data suggest that the overwhelming majority of gastroenterologists in the U.S. enthusiastically support them.65, 66 Interestingly, fear of litigation from missed lesions appears to be a significant motivating factor of screening behavior.66

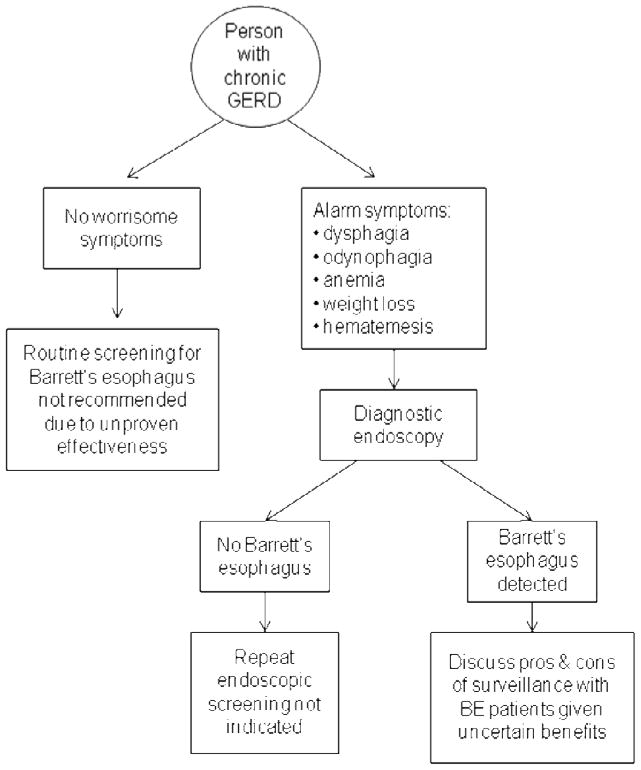

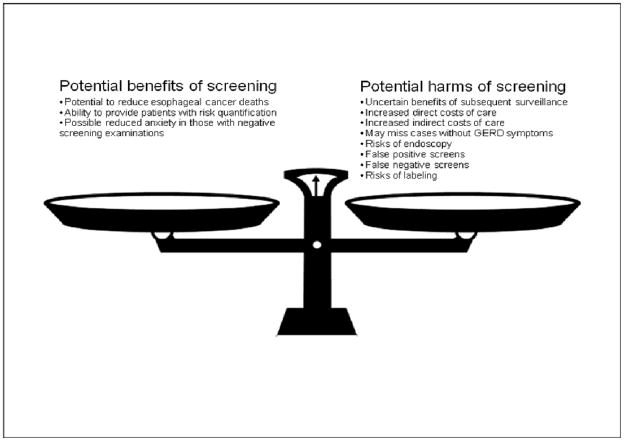

Recommendations for Patient

The patient described in the scenario above has typical GERD symptoms, and received appropriate initial management including a trial of lifestyle modification. He is in a high risk category for BE in that he has a history of GERD for over 5 years, is over 50 years of age, and is a white male. However, he does not have any alarm symptoms that would prompt a diagnostic endoscopic exam. A simple algorithm summarizes an approach to BE screening in GERD patients (Figure 2). At this time, there is insufficient evidence to recommend routine screening for BE or esophageal cancer in persons with GERD, even those with risk factors for BE, and, based on the evidence and guidelines discussed above, this patient would not require endoscopic screening for BE. It is incumbent on physicians who elect to discuss endoscopic screening with patients to fully inform them of the potential pros and cons of this maneuver, as well as the weak nature of the data supporting endoscopic screening (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Modified diagram for use of endoscopy in the setting of GERD, based on published AGA and ACG guidelines.

GERD: Gastroesophageal reflux disease

Figure 3.

Weighing the potential benefits and harms of screening for Barrett’s esophagus amongst patients with Gastroesophageal reflux disease

Summary

Whether persons with GERD should be screened for BE is a common question of both primary care physicians and gastroenterologists alike. Current guidelines recommend either no screening or screening only in individuals at high risk of esophageal cancer. Esophageal cancer is a relatively rare entity in patients with heartburn, and the vast majority of patients with GERD are unlikely to benefit from screening for BE. The evidence supporting screening efforts is weak and inconsistent. Therefore, wide scale endoscopic screening in its currently practiced form cannot be recommended on a routine basis. Further developments in technology may make screening more effective and cost-effective. Finally, the changing epidemiology of this cancer demands that we revisit this issue frequently, as the value of effective screening would presumably increase as the incidence of esophageal cancer rises. While lack of evidence in favor of endoscopic screening does not indicate lack of efficacy, until more data are available to support this practice, screening efforts might be better directed at interventions with proven benefits.

Footnotes

References

- 1.Locke GR, 3rd, Talley NJ, Fett SL, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ., 3rd Prevalence and clinical spectrum of gastroesophageal reflux: a population-based study in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:1448–56. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(97)70025-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Csendes A, Smok G, Burdiles P, Quesada F, Huertas C, Rojas J, Korn O. Prevalence of Barrett's esophagus by endoscopy and histologic studies: a prospective evaluation of 306 control subjects and 376 patients with symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux. Dis Esophagus. 2000;13:5–11. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-2050.2000.00065.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ronkainen J, Aro P, Storskrubb T, Johansson SE, Lind T, Bolling-Sternevald E, Vieth M, Stolte M, Talley NJ, Agreus L. Prevalence of Barrett's esophagus in the general population: an endoscopic study. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:1825–31. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.08.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lieberman DA, Oehlke M, Helfand M. Risk factors for Barrett's esophagus in community-based practice. GORGE consortium. Gastroenterology Outcomes Research Group in Endoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:1293–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Winters C, Jr, Spurling TJ, Chobanian SJ, Curtis DJ, Esposito RL, Hacker JF, 3rd, Johnson DA, Cruess DF, Cotelingam JD, Gurney MS, et al. Barrett's esophagus. A prevalent, occult complication of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterology. 1987;92:118–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anderson LA, Murray LJ, Murphy SJ, Fitzpatrick DA, Johnston BT, Watson RG, McCarron P, Gavin AT. Mortality in Barrett's oesophagus: results from a population based study. Gut. 2003;52:1081–4. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.8.1081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eckardt VF, Kanzler G, Bernhard G. Life expectancy and cancer risk in patients with Barrett's esophagus: a prospective controlled investigation. Am J Med. 2001;111:33–7. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(01)00745-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moayyedi P, Burch N, Akhtar-Danesh N, Enaganti SK, Harrison R, Talley NJ, Jankowski J. Mortality rates in patients with Barrett's oesophagus. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27:316–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03582.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hameeteman W, Tytgat GN, Houthoff HJ, van den Tweel JG. Barrett's esophagus: development of dysplasia and adenocarcinoma. Gastroenterology. 1989;96:1249–56. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(89)80011-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hamilton SR, Smith RR. The relationship between columnar epithelial dysplasia and invasive adenocarcinoma arising in Barrett's esophagus. Am J Clin Pathol. 1987;87:301–12. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/87.3.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miros M, Kerlin P, Walker N. Only patients with dysplasia progress to adenocarcinoma in Barrett's oesophagus. Gut. 1991;32:1441–6. doi: 10.1136/gut.32.12.1441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Drewitz DJ, Sampliner RE, Garewal HS. The incidence of adenocarcinoma in Barrett's esophagus: a prospective study of 170 patients followed 4.8 years. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:212–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spechler SJ, Robbins AH, Rubins HB, Vincent ME, Heeren T, Doos WG, Colton T, Schimmel EM. Adenocarcinoma and Barrett's esophagus. An overrated risk? Gastroenterology. 1984;87:927–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Falk GW. Barrett's esophagus. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:1569–91. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.33427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chow WH, Finkle WD, McLaughlin JK, Frankl H, Ziel HK, Fraumeni JF., Jr The relation of gastroesophageal reflux disease and its treatment to adenocarcinomas of the esophagus and gastric cardia. JAMA. 1995;274:474–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Farrow DC, Vaughan TL, Sweeney C, Gammon MD, Chow WH, Risch HA, Stanford JL, Hansten PD, Mayne ST, Schoenberg JB, Rotterdam H, Ahsan H, West AB, Dubrow R, Fraumeni JF, Jr, Blot WJ. Gastroesophageal reflux disease, use of H2 receptor antagonists, and risk of esophageal and gastric cancer. Cancer Causes Control. 2000;11:231–8. doi: 10.1023/a:1008913828105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lagergren J, Bergstrom R, Lindgren A, Nyren O. Symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux as a risk factor for esophageal adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:825–31. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199903183401101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shaheen N, Ransohoff DF. Gastroesophageal reflux, barrett esophagus, and esophageal cancer: scientific review. JAMA. 2002;287:1972–81. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.15.1972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2006. National Cancer Institute; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bytzer P, Christensen PB, Damkier P, Vinding K, Seersholm N. Adenocarcinoma of the esophagus and Barrett's esophagus: a population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:86–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.00776.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Devesa SS, Blot WJ, Fraumeni JF., Jr Changing patterns in the incidence of esophageal and gastric carcinoma in the United States. Cancer. 1998;83:2049–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wei JT, Shaheen N. The changing epidemiology of esophageal adenocarcinoma. Semin Gastrointest Dis. 2003;14:112–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Greenstein AJ, Litle VR, Swanson SJ, Divino CM, Packer S, McGinn TG, Wisnivesky JP. Racial disparities in esophageal cancer treatment and outcomes. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:881–8. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9664-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cancer Facts & Figures 2009. American Cancer Society; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Djarv T, Lagergren J, Blazeby JM, Lagergren P. Long-term health-related quality of life following surgery for oesophageal cancer. Br J Surg. 2008;95:1121–6. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parekh K, Iannettoni MD. Complications of esophageal resection and reconstruction. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007;19:79–88. doi: 10.1053/j.semtcvs.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shaheen NJ, Crosby MA, Bozymski EM, Sandler RS. Is there publication bias in the reporting of cancer risk in Barrett's esophagus? Gastroenterology. 2000;119:333–8. doi: 10.1053/gast.2000.9302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Sandick JW, van Lanschot JJ, Kuiken BW, Tytgat GN, Offerhaus GJ, Obertop H. Impact of endoscopic biopsy surveillance of Barrett's oesophagus on pathological stage and clinical outcome of Barrett's carcinoma. Gut. 1998;43:216–22. doi: 10.1136/gut.43.2.216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Corley DA, Levin TR, Habel LA, Weiss NS, Buffler PA. Surveillance and survival in Barrett's adenocarcinomas: a population-based study. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:633–40. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.31879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jaspersen D, Kulig M, Labenz J, Leodolter A, Lind T, Meyer-Sabellek W, Vieth M, Willich SN, Lindner D, Stolte M, Malfertheiner P. Prevalence of extra-oesophageal manifestations in gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: an analysis based on the ProGERD Study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17:1515–20. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01606.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rex DK, Cummings OW, Shaw M, Cumings MD, Wong RK, Vasudeva RS, Dunne D, Rahmani EY, Helper DJ. Screening for Barrett's esophagus in colonoscopy patients with and without heartburn. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1670–7. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gerson LB, Banerjee S. Screening for Barrett's esophagus in asymptomatic women. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70:867–73. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2009.04.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gerson LB, Shetler K, Triadafilopoulos G. Prevalence of Barrett's esophagus in asymptomatic individuals. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:461–7. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.34748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ward EM, Wolfsen HC, Achem SR, Loeb DS, Krishna M, Hemminger LL, DeVault KR. Barrett's esophagus is common in older men and women undergoing screening colonoscopy regardless of reflux symptoms. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:12–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00379.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zagari RM, Fuccio L, Wallander MA, Johansson S, Fiocca R, Casanova S, Farahmand BY, Winchester CC, Roda E, Bazzoli F. Gastro-oesophageal reflux symptoms, oesophagitis and Barrett's oesophagus in the general population: the Loiano-Monghidoro study. Gut. 2008;57:1354–9. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.145177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Inadomi JM, Sampliner R, Lagergren J, Lieberman D, Fendrick AM, Vakil N. Screening and surveillance for Barrett esophagus in high-risk groups: a cost-utility analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:176–86. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-3-200302040-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lagergren J, Ye W, Bergstrom R, Nyren O. Utility of endoscopic screening for upper gastrointestinal adenocarcinoma. JAMA. 2000;284:961–2. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.8.961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sackett D, Haynes R, Guyatt G, et al. Clinical Epidemiology: A Basic Science for Clinical Medicine. Little; Brown: 1991. Early Diagnosis. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dellon ES, Shaheen NJ. Does screening for Barrett's esophagus and adenocarcinoma of the esophagus prolong survival? J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:4478–82. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.19.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Peters JH, Clark GW, Ireland AP, Chandrasoma P, Smyrk TC, DeMeester TR. Outcome of adenocarcinoma arising in Barrett's esophagus in endoscopically surveyed and nonsurveyed patients. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1994;108:813–21. discussion 821–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rubenstein JH, Sonnenberg A, Davis J, McMahon L, Inadomi JM. Effect of a prior endoscopy on outcomes of esophageal adenocarcinoma among United States veterans. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68:849–55. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.02.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Harris RP, Helfand M, Woolf SH, Lohr KN, Mulrow CD, Teutsch SM, Atkins D. Current methods of the US Preventive Services Task Force: a review of the process. Am J Prev Med. 2001;20:21–35. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(01)00261-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang KK, Sampliner RE. Updated guidelines 2008 for the diagnosis, surveillance and therapy of Barrett's esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:788–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.01835.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hirota WK, Zuckerman MJ, Adler DG, Davila RE, Egan J, Leighton JA, Qureshi WA, Rajan E, Fanelli R, Wheeler-Harbaugh J, Baron TH, Faigel DO. ASGE guideline: the role of endoscopy in the surveillance of premalignant conditions of the upper GI tract. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:570–80. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Amamra N, Touzet S, Colin C, Ponchon T. Current practice compared with the international guidelines: endoscopic surveillance of Barrett's esophagus. J Eval Clin Pract. 2007;13:789–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2006.00754.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ofman JJ, Shaheen NJ, Desai AA, Moody B, Bozymski EM, Weinstein WM. The quality of care in Barrett's esophagus: endoscopist and pathologist practices. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:876–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03637.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Spechler SJ, Zeroogian JM, Antonioli DA, Wang HH, Goyal RK. Prevalence of metaplasia at the gastro-oesophageal junction. Lancet. 1994;344:1533–6. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)90349-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sharma P. Low-grade dysplasia in Barrett's esophagus. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:1233–8. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.07.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Alikhan M, Rex D, Khan A, Rahmani E, Cummings O, Ulbright TM. Variable pathologic interpretation of columnar lined esophagus by general pathologists in community practice. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;50:23–6. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(99)70339-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rubenstein JH, Inadomi JM. Defining a clinically significant adverse impact of diagnosing Barrett's esophagus. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;40:109–15. doi: 10.1097/01.mcg.0000196186.19426.4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Crockett SD, Lippmann QK, Dellon ES, Shaheen NJ. Health-related quality of life in patients with Barrett's esophagus: a systematic review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:613–23. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.02.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fisher D, Jeffreys A, Bosworth H, Wang J, Lipscomb J, Provenzale D. Quality of life in patients with Barrett's esophagus undergoing surveillance. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:2193–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05972.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shaheen NJ, Green B, Medapalli RK, Mitchell KL, Wei JT, Schmitz SM, West LM, Brown A, Noble M, Sultan S, Provenzale D. The perception of cancer risk in patients with prevalent Barrett's esophagus enrolled in an endoscopic surveillance program. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:429–36. doi: 10.1016/j.gastro.2005.05.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shaheen NJ, Dulai GS, Ascher B, Mitchell KL, Schmitz SM. Effect of a new diagnosis of Barrett's esophagus on insurance status. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:577–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.41422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Preiss C, Charton JP, Schumacher B, Neuhaus H. A randomized trial of unsedated transnasal small-caliber esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) versus peroral small-caliber EGD versus conventional EGD. Endoscopy. 2003;35:641–6. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-41513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bhardwaj A, Hollenbeak CS, Pooran N, Mathew A. A meta-analysis of the diagnostic accuracy of esophageal capsule endoscopy for Barrett's esophagus in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:1533–9. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wolfsen HC. New technologies for imaging of Barrett's esophagus. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2009;18:487–502. doi: 10.1016/j.soc.2009.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Haringsma J. Barrett's oesophagus: new diagnostic and therapeutic techniques. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 2002:9–14. doi: 10.1080/003655202320621382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Isenberg G, Sivak MV, Jr, Chak A, Wong RC, Willis JE, Wolf B, Rowland DY, Das A, Rollins A. Accuracy of endoscopic optical coherence tomography in the detection of dysplasia in Barrett's esophagus: a prospective, double-blinded study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:825–31. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2005.07.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Inadomi JM, Somsouk M, Madanick RD, Thomas JP, Shaheen NJ. A cost-utility analysis of ablative therapy for Barrett's esophagus. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:2101–2114. e1–6. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.02.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kahrilas PJ, Shaheen NJ, Vaezi MF, Hiltz SW, Black E, Modlin IM, Johnson SP, Allen J, Brill JV. American Gastroenterological Association Medical Position Statement on the management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1383–1391. 1391, e1–5. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.08.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.DeVault KR, Castell DO. Updated guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:190–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.41217.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lichtenstein DR, Cash BD, Davila R, Baron TH, Adler DG, Anderson MA, Dominitz JA, Gan SI, Harrison ME, 3rd, Ikenberry SO, Qureshi WA, Rajan E, Shen B, Zuckerman MJ, Fanelli RD, VanGuilder T. Role of endoscopy in the management of GERD. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:219–24. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Playford RJ. New British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) guidelines for the diagnosis and management of Barrett's oesophagus. Gut. 2006;55:442. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.083600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lin OS, Mannava S, Hwang KL, Triadafilopoulos G. Reasons for current practices in managing Barrett's esophagus. Dis Esophagus. 2002;15:39–45. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-2050.2002.00221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rubenstein JH, Saini SD, Kuhn L, McMahon L, Sharma P, Pardi DS, Schoenfeld P. Influence of malpractice history on the practice of screening and surveillance for Barrett's esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:842–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01689.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]