Abstract

Introduction

Opioids are powerful analgesics but are also common drugs of abuse. Few studies have examined how neuropathic pain alters the pharmacology of opioids in modulating limbic pathways that underlie abuse liability.

Methods

Rats with or without spinal nerve ligation (SNL) were implanted with electrodes into the left ventral tegmental area and trained to lever press for electrical stimulation. The effects of morphine, heroin, and cocaine on facilitating electrical stimulation of the ventral tegmental area and mechanical allodynia were assessed in SNL and control subjects.

Results

Responding for electrical stimulation of the ventral tegmental area was similar in control and SNL rats. The frequency at which rats emitted 50% of maximal responding was 98.2 ± 5.1 Hz (mean ± s.e.m.) and 93.7 ± 2.8 Hz in control and SNL rats, respectively. Morphine reduced the frequency at which rats emitted 50% of maximal responding in control (maximal shift of 14.8 ±3.1 Hz) but not SNL (2.3 ± 2.2 Hz) rats. Heroin was less potent in SNL rats while cocaine produced similar shifts in control (42.3 ± 2.0 Hz) and SNL (37.5 ± 4.2 Hz) rats.

Conclusions

Nerve injury suppressed potentiation of electrical stimulation of the ventral tegmental area by opioids, suggesting that the positive reinforcing effects are diminished by chronic pain. Given concerns regarding prescription opioid abuse, developing strategies that assess both analgesia and abuse liability within the context of chronic pain may aid in determining which opioids are most suitable for treating chronic pain when abuse is a concern.

Introduction

Treatment of neuropathic pain with opioids remains controversial due to concerns regarding abuse potential. 1 These concerns are highlighted by the fact that treatment of neuropathic pain typically requires much larger doses of opioids than those used to treat acute pain 2. Although much effort has been spent developing animal models to study the pathophysiology of this disease 3, few studies have addressed the extent to which neuropathic pain alters the rewarding effects of opioids which likely underlie opioid misuse in this population. This study addresses this issue by assessing opioid facilitation of rewarding electrical brain stimulation in rats with and without neuropathic pain.

Neuropathic pain suppresses the reinforcing effects of opioids in rodents. Dose response curves for mu opioid receptor (MOR) agonists in maintaining self-administration are shifted to the right in nerve-injured rats, and only doses that alleviate mechanical allodynia maintain self-administration following nerve injury 4. Similarly, nerve injury decreases morphine’s ability to induce conditioned place preference, a paradigm thought to be an indirect measure of a drug’s rewarding effects, in both rats 5 and mice 6. A substantial literature implicates dopamine in mediating the rewarding effects of many abused drugs, including opioids. Specifically, dopaminergic neurons of the ventral tegmental area (VTA) project extensively to the nucleus accumbens, and release of dopamine in this region is thought to represent a key neural substrate for reward 7. The VTA contains MOR’s located predominantly on non-dopaminergic cells 8 and opioids increase the firing of VTA dopaminergic neurons 9 presumably via disinhibition of dopaminergic cell bodies within the VTA. Previous work reveals that dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens following systemic administration of morphine is suppressed in nerve-injured rats 5. Collectively, these findings suggest that neuropathic pain alters classical reward circuitry in rodents, resulting in altered opioid pharmacology.

One particularly useful method to study opioid activity within the VTA is intracranial electrical self-stimulation (ICSS). ICSS is an operant paradigm that pairs an operant response with brief electrical stimulation of a discrete brain region. Rats will lever press to receive electrical stimulation of the VTA, which causes a substantial release of dopamine in the nucleus accumbens 10. Under these conditions, responding is directly related to the intensity and frequency of stimulation, such that intensity- and frequency-response curves can be generated that mirror pharmacological dose-response curves 11,12. Pharmacology studies reveal that dopamine and MOR agonists facilitate VTA ICSS, indicated by their ability to produce leftward shifts in VTA ICSS frequency response curves in rats 13. To this end, ICSS has proven to be a valuable tool for assessing the effects of drugs or environmental conditions on a discrete pathway within the limbic system, which is difficult to do with systemic drug self-administration. Therefore the application of this technique to a physiological or pharmacological question can complement drug self-administration studies.

The effect of spinal nerve ligation (SNL) on rewarding electrical brain stimulation and modulation by opioids has not been documented. Given that previous work suggests that morphine is less effective in stimulating dopamine activity within the limbic system following nerve injury5, we hypothesized that opioid facilitation of VTA ICSS would be suppressed in nerve-injured rats. We therefore assessed the ability of the MOR agonists morphine and heroin to shift VTA ICSS frequency-response curves to the left in rats with and without neuropathic pain. In addition, the anti-allodynic effects of each drug were assessed using von Frey filaments. Additionally, facilitation of VTA ICSS by cocaine was examined in SNL and control rats to determine if the effects of neuropathic pain were selective for opioids, or produced a generalized effect on this system.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

Subjects consisted of 26 male, Fisher 344 rats (9 SNL rats and 11 control rats were used exclusively for VTA ICSS, 4 SNL rats were used exclusively for determining the effects of drugs on paw withdrawal threshold (PWT), and 2 SNL rats were used for both VTA ICSS and determining drug effects on PWT). Rats weighed 300–350 g at the start of the experiment (Harlan Laboratories, Raleigh, NC), were group-housed, and were maintained on a reversed light-dark cycle (dark 05:00–17:00) in a temperature and humidity controlled environment immediately adjacent to the room in which all behavioral experiments were performed. Food and water were available ad libitum except during behavioral testing. All procedures were conducted in accordance with the guidelines adopted by the Committee for Research and Ethical Issues of the International Association for the Study of Pain and were approved by the Animal Care and use Committee of Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, North Carolina.

Surgeries

Electrode Implantation

Rats were anesthetized with pentobarbital (50 mg/kg, intraperitoneal) and atropine methyl nitrate (10mg/kg, intraperitoneal). Rats were placed in a stereotaxic frame and platinum bipolar stimulating electrodes (Plastics One, Roanoke, VA) were implanted into the left VTA at a 10° angle (2.3mm anterior to lambda, 0.6mm lateral from the midline, and 8.5mm below the skull surface). Electrodes were permanently secured to the skull by three stainless steel screws embedded in dental acrylic. Rats were given penicillin G procaine (75,000 U, intramuscular) to prevent post-surgical infection.

Spinal Nerve Ligation

Immediately following electrode implantation, a portion of rats were subjected to SNL 14. Briefly, a 3cm incision was made in the back using the iliac crests as a midpoint. An incision was then made in the underlying muscle, which was separated by both sharp and blunt dissection to expose the left transverse process of the fifth lumbar vertebra. The transverse process was removed using bone microrongeurs, and the fifth lumbar nerve was exteriorized from underneath the spinal column using a small metal hook and ligated using 4.0 silk suture with sufficient pressure to cause the nerve to bulge on each side of the ligature. The sixth lumbar nerve was exteriorized from underneath the iliac bone at the sciatic notch and ligated in a similar manner. All muscle layers were sutured using 4.0 chromic gut, the skin was sutured using 4.0 nylon suture, and exterior wounds were dressed with antibiotic powder (Polysporin; Pfizer Healthcare, Morris Plains, NJ).

Paw Withdrawal Threshold

To verify development of mechanical allodynia following SNL, PWT’s were determined according to previously published methods using von Frey filaments ranging in strength from 0.6 to 26.0 g (Touch Test Sensory Evaluators; Stoelting, Wood Dale, IL) 15 for all animals using Dixon non-parametric statistics 16. After a minimum of 14 days recovery from electrode implantation and SNL, withdrawal thresholds were determined and rats were considered allodynic if the withdrawal threshold was 4.0g or less; development of allodynia was a requisite for inclusion of SNL rats in the current study. To determine if the drugs used during VTA ICSS alleviated established mechanical allodynia, baseline PWT’s were determined 20 minutes prior to intraperitoneal drug injections. PWT’s were then assessed 15, 60, and 120 minutes post-injection in a portion of rats subjected to SNL.

Drugs

Morphine sulfate was purchased as a 15 mg/ml sterile solution (Baxter Healthcare; Deerfield, IL). Heroin hydrochloride and cocaine hydrochloride were obtained from the Drug Supply Program of the National Institute on Drug Abuse (Rockville, MD), dissolved in 0.9% (wt/vol) saline, and sterilized by filtration through a 0.22 µm nitrocellulose filter. All drugs were diluted using 0.9% (wt/vol) saline, pH 7.4.

Intracranial Self-Stimulation (ICSS)

Apparatus

Commercially available operant equipment was used consisting of an operant chamber containing a lever located 5 cm above a grid bar floor, a stimulus lamp located 2 cm above the lever, a house light located outside of the operant chamber, and a tone generator (Med Associates Inc., St. Albans, VT). The operant chamber was housed within a sound- and light- attenuating enclosure containing a ventilation fan. An ICSS stimulator controlled by a computer software program (Med Associates Inc.) that controlled all stimulation parameters and data collection was located outside of the enclosure. A 2-channel swivel commutator (Model SLC2C, Plastics One) located above the operant chamber connected the electrodes to the ICSS stimulator via 25cm cables (Plastics One).

Behavioral Procedure

After a minimum of 14 days recovery from surgery, rats were trained to lever press for brain stimulation. Illumination of the stimulus light above the lever indicated stimulation availability. Each lever press resulted in a 0.5-sec train of rectangular alternating cathodal and anodal pulses (0.1-ms pulse durations), and was accompanied by the stimulus light turning off, the houselight illuminating, and operation of the tone. Responses during the 0.5-sec stimulation period provided no additional stimulation and were not recorded.

To determine the lowest stimulation intensity (current) that maintained high rates of responding, daily intensity-rate curves were generated. These 1-hr sessions consisted of six 10-minute components, with each component subdivided into ten 1-minute trials. Each trial began with a 5-sec timeout period, a 5-sec priming period in which rats received 5 noncontingent stimulations, and a 50-sec response period in which lever presses resulted in stimulation and were recorded. During these sessions the frequency of stimulation was held constant (156 Hz) and a series of 10 intensities (200-20 uA, 20uA increments corresponding to each trial) were presented in descending order. For data analysis, response rates during the first 2 components of each session were discarded since they were often highly variable and response rates during components 3–6 were averaged to create a single intensity-rate curve for each session. For each session the intensity that maintained 80% of maximal responding (EC80) was determined using Prism software (sigmoidal-dose response, variable slope; Graph Pad, La Jolla, CA), and responding was deemed stable when the EC80’s of three consecutive sessions varied by <10% of the average EC80 of the three sessions. The average EC80 (intensity) of these three sessions was used for frequency-rate curve sessions, and was adjusted if needed.

Daily frequency-rate curves were generated similarly to the intensity-rate curves except that the intensity was held constant (unique to each animal) and a series of 10 frequencies (156-45 Hz, 0.06 log increments corresponding to each trial) were presented in descending order. Test sessions consisted of 7 components with a 15 or 60 minute timeout period between components 4 and 5, during which time rats received 1 mL/kg intraperitoneal injections of saline (0.9% wt/vol), morphine (0.3 – 6 mg/kg), heroin (0.03 – 1 mg/kg), or cocaine (0.3 – 10 mg/kg). For data analysis, the 2 components preceding drug injection (3 & 4) and the 3 components following drug injection (5, 6, & 7) were averaged and compared using Prism software (sigmoidal-dose response, variable slope; Graph Pad). Drug test sessions were separated by at least 1 day. Saline was administered to each animal first, followed by administration of morphine or cocaine on alternate testing days. Heroin was tested after the morphine and cocaine dose-effect curves were completed followed finally by testing effective doses of morphine at the 60 min pretreatment time. Preliminary experiments were performed to determine the highest possible doses of each drug that could be administered without decreasing maximum response rates for VTA ICSS (data not shown in Results). All test sessions were performed between 1–5 months post surgery in both groups of rats. Additional animals were added to the study as needed due to attrition from electrode loss or decreases in baseline responding for VTA ICSS with time.

Histology

Rats were sacrificed by carbon dioxide asphyxiation. Brains were rapidly removed and frozen in isopentane (−35°C) and were stored at −80°C. Coronal sections (25µm) around the electrode tract were obtained using a cryostat to confirm electrode placement within the VTA (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Schematic showing the location of stimulating electrodes within the ventral tegmental area for control and spinal nerve-ligated (SNL) rats.

Numbers next to diagrams indicate the distance anterior to the interaural line according to the atlas of Paxinos and Watson.24

Data Analysis

Data for PWT’s was analyzed using a two-way ANOVA with drug dose and time after infusion serving as the independent variables. The EF50 (frequency at which rats emitted 50% of maximal responding) and maximum response rate for VTA ICSS was calculated using Prism software (sigmoidal-dose response, variable slope; Graph Pad). The effect of drug treatment and SNL on VTA ICSS was analyzed using a two-way ANOVA with drug dose and treatment condition (SNL or control) serving as the independent variables and ΔEF50 (EF50 prior to injection – EF50 after injection) or maximal response rates serving as the dependent measures. Post-hoc analyses within the control or SNL groups were made using Dunnett’s t-test for multiple comparisons with saline injection serving as control. Post-hoc comparisons between control and SNL groups were made using Tukey’s HSD. A two-tailed p-value of 0.05 or less was considered statistically significant.

Results

Development of mechanical allodynia

PWT’s were significantly different between control and SNL rats implanted with VTA electrodes [F(1,21)=71.0, p<0.0001]. All rats implanted with VTA electrodes and subjected to SNL developed mechanical allodynia, with average PWT’s of 2.21 ± 0.25 g (mean ± s.e.m., Figure 2). Rats implanted with VTA electrodes but not subjected to SNL did not develop mechanical allodynia, with average PWT’s of 15.15 ± 1.51 (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Development of mechanical allodynia following spinal nerve ligation (SNL) and baseline responding for electrical stimulation of the ventral tegmental area in control and SNL rats.

(A) Paw withdrawal thresholds (PWT) were assessed between 14–21 days after surgery using von Frey filaments in control and SNL rats. (B) Frequency-response curves for baseline responding were generated by averaging the third and fourth components preceding saline administration (prior to any drug treatments). The y-axis indicates the number of self-stimulations (0.5-sec) during each 50-sec trial for each frequency (x-axis). Data shown are averages across control (n=11) and SNL (n=11) rats. Average current intensities during baseline responding were 139.6 (14.23) uA for control and 138.6 (9.83) uA for SNL rats. # Significantly different from control rats P ≤ 0.05.

Intracranial self-stimulation

Effect of SNL on baseline VTA ICSS

Electrical stimulation maintained responding in a frequency-dependent manner in both control and SNL rats. There was no significant effect of SNL on VTA ICSS compared to control rats with either the EF50 or the maximal response rate (Figure 2). The EF50 for VTA ICSS in SNL rats was 93.7 ± 2.8 Hz and for control rats was 98.3 ± 5.1 Hz [F(1,20)=0.6, p=0.43]. The maximal response rate in SNL rats was 38.4 ± 1.4 resp/trial and for control rats was 38.3 ± 2.3 resp/trial [F(1,20)=0.001, p=0.98].

Morphine

The effect of 15 min pretreatment with morphine in shifting the frequency response curves to the left was significantly different between control and SNL rats [F(1,80)=6.1, p=0.02], and this effect was dose-dependent [F(4,80)=5.1, p=0.001] (Figure 3). There was a significant interaction between SNL vs. control and morphine dose [F(4,80)=2.7, p=0.03]. In the control group morphine significantly increased ΔEF50 values at all doses of 1mg/kg and greater compared to saline [F(4,41)=5.3, p=0.002]. In contrast, in the SNL group morphine did not significantly alter the ΔEF50 compared to saline at any dose [F(4,38)=0.8, p=0.54] and saline alone did not alter the ΔEF50 values in either group (p>0.05).

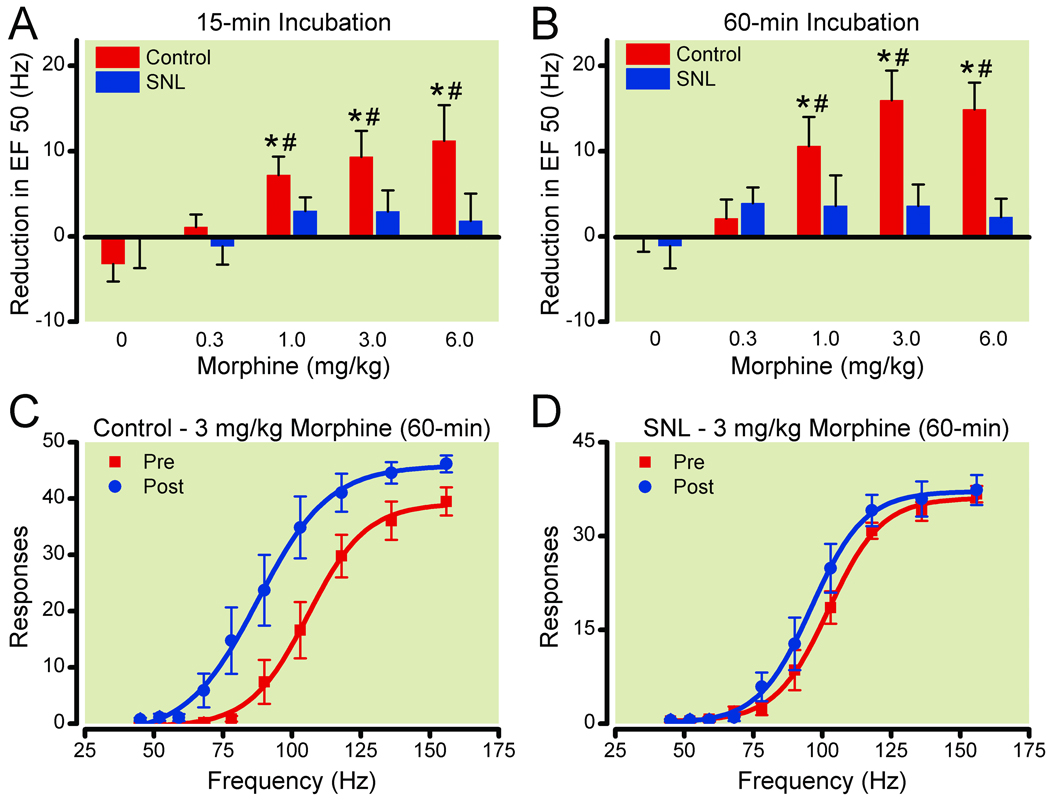

Figure 3. Effects of spinal nerve ligation (SNL) on morphine facilitation of electrical stimulation of the ventral tegmental area for drug incubation times of 15-min (A) and 60-min (B).

Reduction in EF50 (frequency at which rats emitted 50% of maximal responding) was calculated by subtracting the EF50 for the three components following drug injection (5–7) from the EF50 for the two components preceding drug injection (3–4) for each dose assessed. Data shown are averages across control (n=7–8) and SNL (n=6–7) rats. Frequency-response curves before and after 3mg/kg morphine (60-min) are shown for control (C, n=8) and SNL (D, n=7) rats. * Significantly different from saline treatment P ≤ 0.05. # Significantly different from SNL rats P ≤ 0.05.

Morphine’s effect on ICSS in the VTA in control rats was greater after 1 hr compared to 15 min pretreatment; however morphine was still without effect in SNL rats (Figure 3). Analysis of the data with the longer morphine pretreatment time revealed a similar effect [F(9,77)=6.4, p<0.0001], with morphine’s effect being dose-responsive [F(4,77)=7.3, p<0.0001] and SNL producing a significant effect on morphine’s ability to shift the EF50 [F(1,77)=9.4, p=0.003]. As with the earlier time point, there was a significant interaction between SNL vs control and morphine dose [F(4,77)=4.3, p=0.004]. In control rats morphine produced significant leftward shifts in the frequency response curves, and ΔEF50 values were dose-dependent [F(4,40)=8.9, p<0.001] with all doses of 1 mg/kg and greater producing a significant effect. As with the earlier pretreatment time, morphine had no effect on the ΔEF50 values at any dose in SNL rats [F(4,36)=1.0, p=0.4] and saline alone did not alter the ΔEF50 values in either group following a 1 hr pretreatment (p>0.05).

Heroin

15 min pretreatment with heroin altered ICSS in the VTA in both control and SNL rats, however significant differences were found between these two groups (Figure 4). Heroin shifted the frequency response curves to the left, producing significant increases in the ΔEF50 values in a dose-responsive manner in both control [F(4,35)=6.5, p=0.0006] and SNL [F(4,41)=8.1, p<0.0001] rats. In the control group heroin significantly increased ΔEF50 values at all doses of 0.1mg/kg and greater compared to saline (p≤0.05). In the SNL group heroin significantly increased ΔEF50 values at all doses of 0.3mg/kg and greater compared to saline (p≤0.05).

Figure 4. Effects of spinal nerve ligation (SNL) on heroin facilitation of electrical stimulation of the ventral tegmental area.

(A) Reduction in EF50 (frequency at which rats emitted 50% of maximal responding) was calculated by subtracting the EF50 for the three components following drug injection (5–7) from the EF50 for the two components preceding drug injection (3–4) for each dose assessed. Data shown are averages across control (n=6–7) and SNL (n=7–8) rats. Frequency-response curves before and after 0.1 mg/kg heroin (15-min) are shown for control (B, n=6) and SNL (C, n=8) rats. * Significantly different from saline treatment P ≤ 0.05.

Cocaine

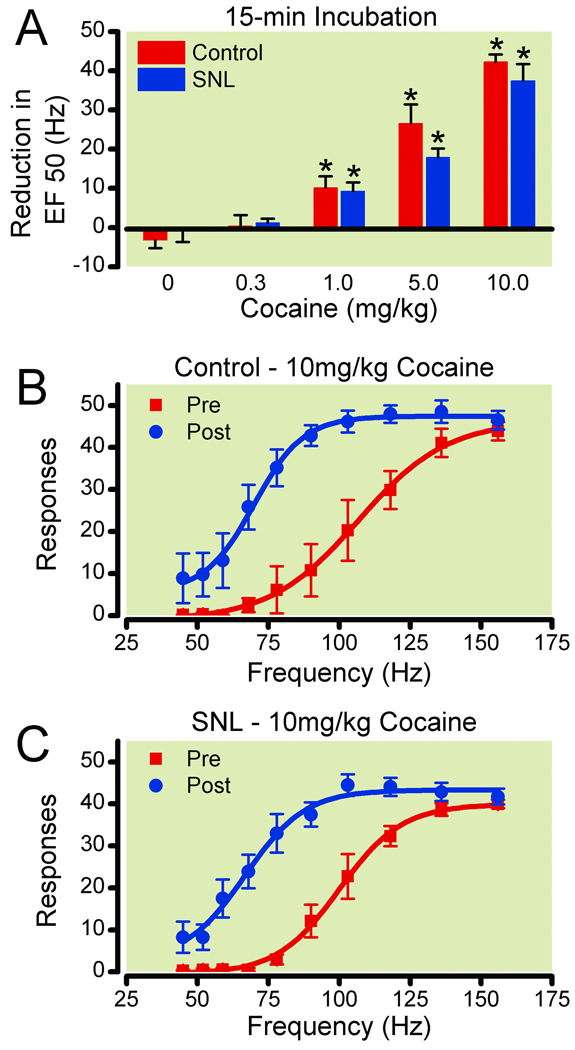

15 min pretreatment with cocaine altered ICSS in the VTA in both control and SNL rats in a similar manner (Figure 5). Cocaine shifted the frequency response curves to the left, producing significant increases in the ΔEF50 values in a dose-responsive manner in both groups of rats [control: F(4,36)=42.5, p<0.0001, SNL: F(4,41)=40.1, p≤0.0001]. Cocaine significantly increased ΔEF50 values at all doses of 1mg/kg and greater compared to saline (p≤0.05). There were no significant differences between control and SNL rats for any dose of cocaine.

Figure 5. Effects of spinal nerve ligation (SNL) on cocaine facilitation of electrical stimulation of the ventral tegmental area.

(A) Reduction in EF50 (frequency at which rats emitted 50% of maximal responding) was calculated by subtracting the EF50 for the three components following drug injection (5–7) from the EF50 for the two components preceding drug injection (3–4) for each dose assessed. Data shown are averages across control (n=6–7) and SNL (n=7–8) rats. Frequency-response curves before and after 10 mg/kg heroin (15-min) are shown for control (B, n=7) and SNL (C, n=8) rats. * Significantly different from saline treatment P ≤ 0.05.

Drug effects on maximal response rate

Both morphine and heroin had no effect on the maximum rate of responding maintained by intracranial stimulation in both groups at any time following injection. Cocaine had no effect on the maximum rate of responding in the control group [F(4,36)=1.0, p=0.4] but did slightly increase the maximum response rate in the SNL group [F(4,41=2.8, p=0.04] at the highest dose studied of 10 mg/kg (39.5±1.4 baseline, 43.5±2 treated, p<0.05).

Drug effects on mechanical allodynia

Morphine and heroin both increased PWT over the range of doses that produced significant increases in ΔEF50 for ICSS (Figure 6). The effects of morphine were dose-dependent [F(3,23)=15.6, p<0.0001; F(3,23)=27.2, p<0.0001, 15 or 60 min post-injection, respectively]. Both 3 and 6 mg/kg morphine significantly increased PWT at these time points compared to saline injection (p<0.05), and the maximum effect occurred 60 min following injection of 6 mg/kg morphine, resulting in a PWT of 16.6±2.1 g. Heroin also produced dose-dependent increases in PWT [F(3,23)=38.4, p<0.0001; F(3,23)=22.8, p<0.0001, 15 or 60 min post-injection, respectively]. Both 0.3 and 1.0 mg/kg of heroin significantly increased PWT at these time points compared to saline (p<0.05), and the maximum effect of heroin (22.1±0.8 g) was greater than that of morphine, occurring 15 min after injection of 1 mg/kg (p≤0.05). Cocaine had no effect on PWT at any dose [F(2,17)=1.6, p=0.2; F(2,17)=1.1, p=0.4, 15 or 60 min post-injection, respectively] (Figure 6). Saline had no effect on PWT at any time following injection [F(2,17)=0.2, p=0.8] (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Drug effects on paw withdrawal thresholds (PWT) in spinal nerve-ligated (SNL) rats.

Dose-effect curves were determined for morphine (A), heroin (B), and cocaine (C) on PWT in SNL rats at the indicated times following an intraperitoneal injection (n=6). * Significantly different from saline treatment P ≤ 0.05.

Discussion

Given the widespread concerns regarding opioid misuse in chronic pain patients, there is a need to determine to what extent the presence of chronic pain alters the abuse potential of opioids. The current study indicates that MOR agonists become less effective in facilitating VTA ICSS following peripheral nerve injury, suggesting that their ability to produce positive reinforcement is diminished by the presence of chronic pain. The diminished effects in SNL rats appear to be specific to opioids, since cocaine was equally effective in facilitating VTA ICSS in both control and SNL rats. These data support our hypothesis that the efficacy of opioids in stimulating the mesolimbic dopaminergic system is suppressed in rats with neuropathic pain.

It is important to highlight differences between the effects of SNL on suppressing morphine and heroin facilitation of ICSS. The facilitating effects of morphine were suppressed to such an extent following SNL that no dose of morphine (0.3 – 6 mg/kg) produced leftward shifts in the frequency response curves following SNL. The complete suppression of morphine’s facilitating effects in SNL rats following 15-min drug incubation was surprising; to further confirm these findings a 60-min pretreatment was used which produced even greater leftward shifts in the frequency rate curves in control subjects, and again morphine failed to facilitate ICSS selectively in SNL rats. In contrast, only one dose of heroin assessed (0.1mg/kg) produced a significant leftward shift in control rats that was not observed in SNL rats; meanwhile heroin was still effective in facilitating VTA ICSS at the two highest doses assessed (0.3 & 1mg/kg) in control and SNL rats. Doses higher than 6mg/kg morphine and 1mg/kg heroin decreased maximal response rates for ICSS (data not shown), and therefore the dose range was restricted to 6mg/kg and 1mg/kg, respectively. From this data, one would predict that morphine and heroin would produce positive reinforcement in control rats, but that only heroin would produce positive reinforcement in SNL rats, albeit at larger doses. Interestingly, this prediction is supported by previous work that assessed opioid self-administration in rats with and without SNL 4. In those experiments, SNL decreased maximal response rates for morphine self-administration compared to SHAM rats to such an extent that responding for morphine in SNL rats no longer was dose-dependent; morphine essentially appeared to not serve as a reinforcer following SNL. In contrast, heroin self-administration was merely shifted to the right in SNL rats compared to SHAM rats, and maximal rates of responding were unaffected; heroin still served as a reinforcer at higher doses following SNL. Taken together, suppression of the reinforcing effects of opioids in each of these paradigms seems to be related to the efficacy of the opioid, such that the reinforcing effects of lower efficacy opioids (morphine) are completely diminished following SNL whereas those of higher efficacy opioids (heroin) can be overcome by increasing the dose.

The mechanism underlying the loss of opioid facilitation of VTA ICSS following SNL appears to not be general disruption of limbic activity. The ability of electrical stimulation of the VTA to maintain operant responding is not altered by SNL; the frequency-response curves and the mean intensities required to maintain responding do not differ between SNL and control rats. Additionally, cocaine’s facilitating effects on VTA ICSS were the same in SNL and control rats suggesting that SNL does not cause a nonspecific disruption in behavior or limbic activity. Therefore the effects appear to be unique to opioids, leaving the possibility that SNL produces a selective disruption in MOR activity. In particular, alterations in MOR G-protein signaling may occur in the VTA, leading to reduced signaling following MOR agonist activation and ultimately suppression of opioid facilitation of VTA ICSS. Previous work supports this notion, since it was shown that morphine-stimulated GTPγS binding in the VTA and morphine-induced dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens are suppressed in nerve-injured rats 5. Similar effects were observed in nerve-injured mice 17, however the mechanism for receptor uncoupling within this circuitry is unclear. It is also unclear if such uncoupling can be reversed with acute or chronic blockade of pain transmission with analgesics, or if the alterations are irreversible.

MOR signaling may be altered following SNL in other brain regions that influence activity within the VTA or receive output from the VTA. Other brain regions that would most likely be involved are those receiving dopaminergic output from the VTA, including the nucleus accumbens, ventral pallidum, and amygdala 7, all of which contain MOR’s. To address this, future studies could examine the degree to which chronic pain alters the facilitating effects of opioids administered locally into each of these discrete brain regions. Given the knowledge of which MOR’s are and are not responsible for this effect, the underlying neural mechanisms responsible for loss of opioid efficacy in facilitating VTA ICSS could be explored.

The suppression of opioid facilitation of rewarding brain stimulation following nerve injury has important implications regarding opioid abuse potential in the presence of chronic pain. Most drugs of abuse, including opioids, increase dopamine transmission throughout the mesolimbic dopaminergic system 13, and their ability to facilitate VTA ICSS is often used as a measure of their abuse potential. Therefore, a reduction in the facilitating effects of opioids on VTA ICSS following SNL indicates a loss of the positive rewarding effects that likely contribute to opioid abuse. Clinically, the notion that opioid abuse potential is reduced by the presence of chronic pain is not new. A recent review suggests that abuse/addiction rates in chronic pain patients are relatively low (~3%),18 although precise rates for opioid misuse remain difficult to determine.

Since this is the first report of opioid effects on VTA ICSS during chronic pain, it is unclear if similar suppression of VTA ICSS will be observed with other opioid compounds. Additionally, it is unclear to what extent drug history alters the facilitatory effects of opioids on VTA ICSS. In the current study rats received all drug conditions, and although repeated testing could potentially impact facilitation of ICSS, the fact that drug history was similar between control and SNL rats suggests that these effects are likely negligible. Additionally, morphine injections were given at the beginning of the study at the 15 min time point and at the end of the study at the 60 min pretreatment condition. Similar potencies were found for facilitation of VTA ICSS in the control group, and morphine had no effect on VTA ICSS in the SNL group, suggesting that drug history likely had a minor role if any on these data. An interesting question with respect to drug history would be if extensive drug exposure (months) prior to nerve-injury would alter the abuse liability of opioids as measured using VTA ICSS. This question is particularly interesting given that one of the greatest predictors of opioid abuse/addiction in chronic pain patients is a previous history of drug abuse18. Ultimately, VTA ICSS has great potential as a preclinical screening tool for assessing the abuse liability of potential opioid as well as nonopioid analgesics during chronic pain.

It was surprising that no differences were observed in baseline responding for VTA ICSS between control and SNL rats. Administration of lactic acid into the peritoneal cavity produces abdominal pain and irritation and has recently been shown to suppress responding for ICSS, an effect that is reversed by pretreatment with morphine19. These data suggest that the presence of severe acute pain diminishes the reinforcing effects of electrical stimulation of ascending dopamine pathways. Lactic acid injected into the peritoneal cavity produces overt abdominal writhing and stretching behavior, and rats will typically cease ongoing behavior during these episodes, which are inhibited by a variety of analgesics including opioids.19 SNL produces few overt behavioral effects however. The difference between the effects of intraperitoneal lactic acid and SNL on ICSS may be the presence of these pronounced behavioral effects, the relative severity of the pain stimulus, or differential effects on the mesolimbic reward pathways. Given that people with chronic pain often suffer from affective disorders such as anxiety and depression20, which suggests that persistent pain leads to an overall negative affective state, it was expected that nerve injury would reduce activity of reward pathways originating within the limbic system, and therefore that SNL rats would be less responsive to rewarding electrical stimulation. However the current data suggest that if SNL decreases activity within the limbic system in rats, that VTA ICSS lacks the sensitivity to detect such an effect of this manipulation. Given that the central amygdala is activated during pain states 21,22 and sends GABAergic projections that synapse directly on dopaminergic cell bodies of the VTA 23, it is plausible that chronic pain increases the activity of these central amygdala GABAergic neurons, causing tonic suppression of dopamine transmission from the VTA in neuropathic rats. The present data suggest however that the basal activity of reward pathways are not significantly inhibited following SNL, at least not to an extent that can be detected using the ICSS methodology. Instead, the present data suggest that dopaminergic reward pathways originating from the VTA are altered in a highly selective manner following SNL in rats, resulting in a specific alteration in opioid pharmacology within this circuitry.

In conclusion, the ability of opioids to facilitate VTA ICSS is suppressed following SNL. This suggests that opioids are less effective in stimulating dopamine transmission originating in the VTA. The effect appears to be restricted to opioids since facilitation of VTA ICSS with cocaine is maintained in neuropathic rats. The current methodology used (VTA ICSS) not only complements previous work using drug self-administration, but adds an additional layer of precision by isolating opioid effects within limbic reward circuitry, which is difficult to do using systemic drug self-administration. Future work should focus on whether similar effects occur with different opioid compounds, as well as determine the underlying mechanisms responsible for opioid suppression following nerve injury. The use of operant techniques such as VTA ICSS may be beneficial as a preclinical tool for screening the abuse liability of novel analgesics, as well as provide useful information regarding the interactions between chronic pain and classical reward circuitry.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Dr. Steve Negus (PhD, Professor, Dept. of Pharmacology and Toxicology, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA, USA) for his helpful advice and discussion regarding the intracranial self-stimulation procedure and data analysis.

Funding statement: Supported by grants DA-022599 (TJM) and T32-DA-007246 (EEE) from the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Work presented at the American Pain Society Annual Meeting in Baltimore, MD. Poster session, May 7, 2010.

References

- 1.Compton WM, Volkow ND. Major increases in opioid analgesic abuse in the United States: Concerns and strategies. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;81:103–107. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benedetti F, Vighetti S, Amanzio M, Casadio C, Oliaro A, Bergamasco B, Maggi G. Dose-response relationship of opioids in nociceptive and neuropathic postoperative pain. Pain. 1998;74:205–211. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(97)00172-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martin TJ, Eisenach JC. Pharmacology of opioid and nonopioid analgesics in chronic pain states. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;299:811–817. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martin TJ, Kim SA, Buechler NL, Porreca F, Eisenach JC. Opioid self-administration in the nerve-injured rat: Relevance of antiallodynic effects to drug consumption and effects of intrathecal analgesics. Anesthesiology. 2007;106:312–322. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200702000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ozaki S, Narita M, Iino M, Sugita J, Matsumura Y, Suzuki T. Suppression of the morphine-induced rewarding effect in the rat with neuropathic pain: Implication of the reduction in mu-opioid receptor functions in the ventral tegmental area. J Neurochem. 2002;82:1192–1198. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.01071.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ozaki S, Narita M, Ozaki M, Khotib J, Suzuki T. Role of extracellular signal-regulated kinase in the ventral tegmental area in the suppression of the morphine-induced rewarding effect in mice with sciatic nerve ligation. J Neurochem. 2004;88:1389–1397. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.02272.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pierce RC, Kumaresan V. The mesolimbic dopamine system: The final common pathway for the reinforcing effect of drugs of abuse? Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2006;30:215–238. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2005.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garzon M, Pickel VM. Plasmalemmal mu-opioid receptor distribution mainly in nondopaminergic neurons in the rat ventral tegmental area. Synapse. 2001;41:311–328. doi: 10.1002/syn.1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gysling K, Wang RY. Morphine-induced activation of A10 dopamine neurons in the rat. Brain Res. 1983;277:119–127. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(83)90913-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hernandez G, Shizgal P. Dynamic changes in dopamine tone during self-stimulation of the ventral tegmental area in rats. Behav Brain Res. 2009;198:91–97. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carlezon WA, Jr, Chartoff EH. Intracranial self-stimulation (ICSS) in rodents to study the neurobiology of motivation. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:2987–2995. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miliaressis E, Rompre PP, Laviolette P, Philippe L, Coulombe D. The curve-shift paradigm in self-stimulation. Physiol Behav. 1986;37:85–91. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(86)90388-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wise RA. Addictive drugs and brain stimulation reward. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1996;19:319–340. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.19.030196.001535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim SH, Chung JM. An experimental model for peripheral neuropathy produced by segmental spinal nerve ligation in the rat. Pain. 1992;50:355–363. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(92)90041-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nichols ML, Bian D, Ossipov MH, Lai J, Porreca F. Regulation of morphine antiallodynic efficacy by cholecystokinin in a model of neuropathic pain in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1995;275:1339–1345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chaplan SR, Bach FW, Pogrel JW, Chung JM, Yaksh TL. Quantitative assessment of tactile allodynia in the rat paw. J Neurosci Methods. 1994;53:55–63. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(94)90144-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ozaki S, Narita M, Iino M, Miyoshi K, Suzuki T. Suppression of the morphine-induced rewarding effect and G-protein activation in the lower midbrain following nerve injury in the mouse: Involvement of G-protein-coupled receptor kinase 2. Neuroscience. 2003;116:89–97. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00699-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fishbain DA, Cole B, Lewis J, Rosomoff HL, Rosomoff RS. What percentage of chronic nonmalignant pain patients exposed to chronic opioid analgesic therapy develop abuse/addiction and/or aberrant drug-related behaviors? A structured evidence-based review. Pain Med. 2008;9:444–459. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2007.00370.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pereira Do Carmo G, Stevenson GW, Carlezon WA, Negus SS. Effects of pain-and analgesia-related manipulations on intracranial self-stimulation in rats: Further studies on pain-depressed behavior. Pain. 2009;144:170–177. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Von Korff M, Simon G. The relationship between pain and depression. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 1996;30:101–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ikeda R, Takahashi Y, Inoue K, Kato F. NMDA receptor-independent synaptic plasticity in the central amygdala in the rat model of neuropathic pain. Pain. 2007;127:161–172. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Neugebauer V, Galhardo V, Maione S, Mackey SC. Forebrain pain mechanisms. Brain Res Rev. 2009;60:226–242. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2008.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Everitt BJ, Parkinson JA, Olmstead MC, Arroyo M, Robledo P, Robbins TW. Associative processes in addiction and reward. The role of amygdala-ventral striatal subsystems. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;877:412–438. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb09280.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Paxinos G, Watson C. The rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates. New York, NY: Academic Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]