Summary

The progression of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) to the B lymphocyte lineage requires that uncommitted progenitors successfully negotiate the transition from multipotency to unipotency, including the loss of self-renewal potential. Previous work identified essential transcription factors that mediate B lineage development. Major advances build on this knowledge and reveal coordinated changes in gene expression occurring within single cells at sequential stages in the B cell differentiation pathway. Recent studies on epigenetic mechanisms also provide a framework within which transcription factor activity, chromatin modifications, and gene expression patterns can be viewed at hierarchical levels to link genotype and phenotype.

Introduction

Hematopoiesis is a key model system for understanding the mechanisms that control tissue regeneration, developmental plasticity, and lineage fate decisions. This is a scientifically exciting area because the basic processes that occur during hematopoiesis are also fundamental to embryogenesis and tissue repair/regeneration. As such knowledge about the molecular mechanisms that control hematopoiesis have broad biological implications.

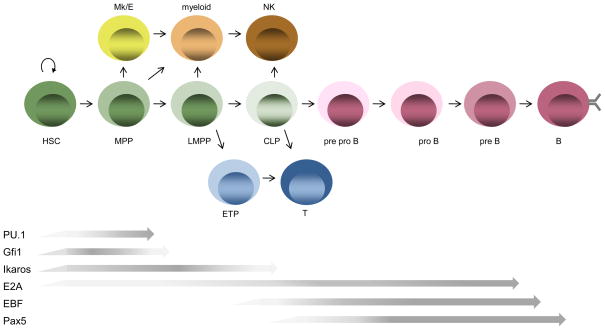

Differentiation of HSCs to B lymphocytes involves progression through multipotent progenitor (MPP), lymphoid/myeloid-primed multipotent progenitor (LMPP) and common lymphoid progenitor (CLP) stages of development, accompanied by the sequential loss of megakaryocyte/erythroid (MEP) and myeloid potentials [1,2] (Figure 1). One powerful characteristic of the hematopoietic model system is the ability to isolate, based on surface phenotype, intermediates that represent developmental stage-specific progenitors. Using defined surface markers, studies over the last ten years have progressed from isolation of phenotypic subsets to isolation of single cells. A core transcriptional network that orchestrates B cell fate specification within sequential developmental contexts is established. The transcription factors Ikaros, PU.1 and E2A regulate lymphoid versus myeloid fate choice while EBF and Pax5 control B cell specification and commitment (Figure 2). Recent progress connects genetic and epigenetic mechanisms during specific developmental transitions between lymphoid progenitors and B cell precursors.

Figure 1.

The development of B cells from HSCs involves progression to multipotent progenitor (MPP), lymphoid/myeloid-primed multipotent progenitor, common lymphoid progenitor, (CLP) and B cell progenitor intermediates prior to B cell commitment. In one current model of developmental progression, establishment of the B lineage fate is accompanied by sequential loss of megakaryocyte/erythrocyte (Mk/E) potential, myeloid potential and T/NK cell potentials.

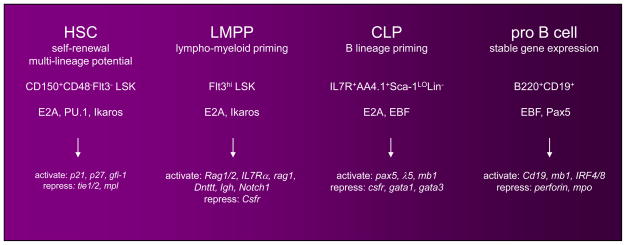

Figure 2.

Hallmark developmental transitions during HSC progression to the B cell fate. Indicated below each major phenotypic stage is the defining functional criteria, surface markers, key transcription factors, and associated target genes. Emphasis is placed on E2A to reflect recent scientific advances.

Here, we review current knowledge of transcription factors and their cis-targets critical for B lineage development. We integrate this transcriptional network within a broader context of recent genome-wide analyses that reveal the patterns of transcription factor binding at sequential developmental stages. Emerging from these studies is a clearer understanding of how the concerted binding of multiple transcription factors (trans-acting factors) at defined regulatory regions (cis-acting elements) regulates gene expression in a developmental stage-specific manner (phenotype). In other words, the gap between genotype and phenotype just got a little smaller.

Transcriptional regulation of B cell development

Progression of HSCs to the B lineage is marked by the loss of pluripotent self-renewal activity and activation of a B cell specific program. During this transition, characteristic low-level gene expression associated with multi-lineage priming gives way to increased expression of genes associated with the B cell fate [3,4]. Genes expressed during multi-lineage priming commonly exhibit bivalent chromatin marks in which both activating and inhibitory modifications to histones and DNA are present [5,6]. Within CD150+ LSK (lineage marker-negative, Sca-1+, c-kit+) stem cells, for example, ~4% of ebf and pax5 promoters bear coincident activating H3K4me3 and inhibitory H3K27me3 modifications [7**]. These bivalent histone marks are subsequently resolved concomitant with changes in the activity of transcription factors that upregulate lymphoid lineage genes and repress genes associated with alternative lineage fates.

The Ikaros transcription factor is a major regulator of HSC progression to the lymphoid lineages. Encoded by the Ikzf1 gene [8], Ikaros suppresses stem cell associated genes including the receptor tyrosine kinases tie1, tie2 and mpl, and induces lymphoid-specific genes including the Dntt nucleotide transferase [9**]. In a powerful experiment, the lymphoid induction potential of Ikaros was shown within single HSCs, the functional level at which lineage fate decisions are made [9**]. Ikaros activity is required in LMPPs and early B cell precursors where it regulates expression of the cytokine receptor flt3, the λ5 pre-B cell receptor chain [10] and rag1/2 genes. Ikaros also regulates immunoglobulin chromatin remodeling [11*]. One critical function of Ikaros is to antagonize the transcription factor PU.1 (purine box factor-1) to direct the lymphoid versus myeloid fate [12].

PU.1, an Ets family transcription factor, regulates gene targets important to both the lymphoid and myeloid lineages including receptors for the cytokines IL-7 and the granulocyte/macrophage (G/M) colony stimulating factors, respectively. PU.1 expression in MPPs restricts MEP fate [13] after which the coordinated interaction of PU.1 and the Ikaros-induced Gfi-1 (growth factor independent-1) transcription factor establishes B versus myeloid fate choice by stabilizing PU.1 levels [12]. PU.1 is maintained at low levels in B cells and at high levels in myeloid cells [14,15]. Engagement of PU.1 motifs within the Sfp1 promoter itself can promote autoamplification in a feed forward loop [16,17]. During lymphopoiesis however, Ikaros induces Gfi-1, which, in turn, blocks PU.1 autoamplification through physical displacement of PU.1 at the Sfp1 promoter [11*]. The biological effect is to reduce PU.1 expression to lymphoid-appropriate levels. In addition to limiting PU.1, Gfi-1 reinforces lymphoid progression by enhancing E2A activity through direct suppression of the inhibitor of DNA binding factor-2 (Id2), an E2A antagonist [18]. Finally, the ability of PU.1 to direct major downstream factors E2A, EBF, Oct-2 and NFκB to defined target genes in a lymphoid lineage-specific manner is one likely mechanism that favors lymphopoiesis versus myelopoiesis [19].

E2A, a basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor, is emerging as an important regulator of HSC self-renewal and of LMPP – but not HSC – lineage restriction. E2A deficient HSCs exhibit diminished self-renewal capability following adoptive transfer, hyperproliferation associated with loss of the p21 cell cycle inhibitor, and a failure to prime lymphoid lineage-associated genes [20**, 21, 22**, 23]. Loss of HSC activity is also observed in mice lacking either the E2A inhibitor Id1 [24,25] or the E2A interaction partner Stem Cell Leukemia (SCL) [26], suggesting an interacting network of E proteins at this stage. E2A is dispensable for the restriction of MEP and myeloid lineage potentials as assessed using single HSCs [20**,22**]. E2A may regulate later dynamics as erythroid and megakaryocyte intermediates are diminished [21]. MPPs and LMPPs are numerically reduced in the absence of E2A [20**,23], and downstream CLPs are virtually ablated [27]. In vivo administration of anti-oxidant restores MPPs but not the LMPP or CLP subsets in E2A deficient mice [22**], thereby defining new activities of E2A independent of lymphoid lineage differentiation.

E2A is an essential regulator of lymphoid specification and restriction of myeloid potential at the LMPP stage [20**]. Gain-of-function and loss-of-function studies show that the balance between E proteins and Id proteins regulates lymphoid versus myeloid fate decisions of LMPPs [28]. In addition to being reduced in number, remnant LMPPs from E2A-deficient mice fail to fully upregulate the Flt3 cytokine receptor [20**,22**] that is essential for development of Flt3hiVCAM-1−LMPPs [29]. E2A does not regulate flt3 transcription per se [20**]. Rather, Hoxa9 and PU.1 regulate flt3 expression, although cooperative interactions between E2A, hoxa9, and PU.1 in LMPPs remain to be established [30]. E2A-deficient LMPPs additionally lack V(D)J recombinase activity [27]. At the molecular level, E2A-deficient LMPPs have decreased expression of the lymphoid associated genes IL7Rα, rag1, Dntt, Igh-6, notch1 and ccr9 [20**], and fail to generate pro-B cells [31]. The E2A inhibitor, HEBalt, an alternative splice product of the HEB locus, emerges as a context-dependent regulator of cell fate choice. HEBalt inhibits B cell outgrowth to the benefit of myeloid cells, but in the presence of Notch ligands, favors T cells over myeloid cells [32].

In summary, three major roles for E2A are emerging. First, E2A appears to be required for efficient HSC self-renewal and persistence, and for lymphoid-lineage priming at this stage. Second, E2A promotes the production and/or maintenance of MPPs and LMPPs, and is required for myeloid restriction in LMPPs. Third, as detailed immediately below, E2A is required for promotion of B lineage progression through a cascade involving the EBF, Pax5 and Foxo1 regulatory factors.

EBF and Pax5 sequentially specify and commit lymphoid precursors to the B cell fate. Forced expression of EBF in MPPs activates the lineage appropriate genes pax5, lambda5, VpreB and Cd79b and represses genes associated with alternative fates including c/EBPα [33] (Figure 2). Binding of the interferon-regulatory factor IRF8 to the ebf promoter results in transcriptional activation of EBF while binding to the Sfp1 promoter represses PU.1 [34]. EBF, in turn, reinforces E2A activity by repressing the Id inhibitors of E2A [35]. Unlike E2A-deficient mice that lack CLPs, EBF-deficient mice have a numerically replete CLP compartment that lacks B lineage potential. At the single cell level, EBF KO CLPs fail to upregulate pax5, Pou2af1 and mb-1 transcripts [36]. Single cell tracing reveals that high levels of rag1 accompany loss of myeloid and NK potential [37**,38*]. Almost all raghi CLPs express EBF, with ~31% of these cells also expressing pax5 and retaining both B and T cell potential in vitro. T cell potential is lost concomitant with full transcriptional activity of EBF. Rag expression in CLPs correlates with Ly6D expression suggesting the value of this surface marker for distinguishing CLPs with global lymphoid potential versus CLPs that are B lineage biased [37**,39*]. Compound haploinsufficiency of EBF and RUNX1 diminishes B lineage specific gene expression resulting in a block in B cell progression [40].

Pax5 maintains the B cell fate [41**,42]. Conditional ablation of pax5 in CD19+ splenocytes leads to a loss of the B cell program and a striking conversion to the T cell fate. In support of these observations, Notch1 signaling in response to delta like ligand 4 leads to a dose dependent inhibition of Pax5 and the B lineage program in the thymus [43]. In humans, ablation of the E2A-EBF-Pax5 pathway is associated with Hodgkin lymphoma in which B cells exhibit a loss of identity uncannily reminiscent of pax5 conditional deletion [42].

Epigenetic regulation of the B cell development

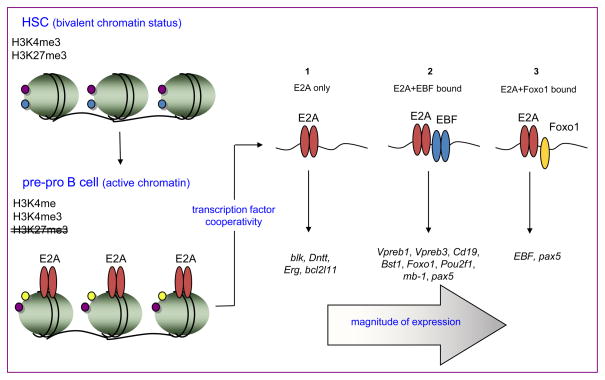

Cell fate decisions are dictated by the activation state of core transcription factors and the access of these factors to select genomic regions. The epigenetic mechanisms that regulate B lineage determination are being revealed at the sequential levels of genome wide analysis (E2A, EBF), a promoter/enhancer complex (pax5), and B cell-specific genes (mb-1, Cd19).

Murre et al. detail the association of E2A binding to cis elements, epigenetic modification, coordinated occupancy by cooperating factors, and transcript abundance at sequential stages of B cell development [44**]. There are two thematic advances in this study. First, the data provide a molecular genetic snapshot of B cells at a developmental transition where they still possess a genotype identical with most other cells in the body yet have a distinct phenotype. Second, this study quantifies the positive effects on gene expression of cooperative transcription factor binding. E2A occupancy near transcription start sites is associated with activating H3K4 monomethylation marks at enhancers and H3K4 trimethylation marks at promoters (Figure 3). About half of the E2A-occupied sites in pre-pro B cells are also occupied in pro-B cells, but proB cells acquire ~10,000 new E2A-bound sites. E2A-occupied sites co-localize with binding motifs of factors essential to the B lineage fate including EBF and PU.1 [44**], the Foxo1 regulator of rag expression [45,46], the CTCF regulator of immunoglobulin locus contraction [47] and Bcl11a [48]. Co-occupancy by E2A and EBF correlates with H3K4 methylation status and an abundance of the hallmark B lineage transcripts VpreB, Cd19, foxo1, Pou2f1, Cd79a, and pax5. These data define a molecular genetic basis for the functional synergy observed between E2A and EBF [49]. Loci enriched for co-occupancy of E2A and Foxo1 include Dntt, the Erg transcription factor, and the pro-apoptotic gene bcl2l11 that encodes Bim. Mice doubly heterozygous for E2A and Foxo1 (e2A+/−foxo1+/−) have reduced B cell progenitors compared to either single heterozygote, thereby directly linking E2A, EBF and FOXO1 in a common pathway [44**]. In another example of lineage-specific cooperativity, the ability of PU.1 to bind to defined targets is influenced by the presence of cooperating factors as enforced expression of E2A increased PU.1 binding sites by 4-fold [19].

Figure 3.

Epigenetic modification and transcription. Bivalent chromatin modifications mark B lineage-specific genes in HSCs. Such genes are considered poised but silent. E2A binding to cis elements is associated with activating H3K4 monomethylation at enhancers and H3K4 trimethylation at promoters. E2A activates EBF and Pax5, initiating a cascade of expression of B cell-specific genes. Transcription factor cooperation elevates the magnitude of gene expression.

Genome-wide analyses reveal EBF-activated and -repressed targets across defined stages of B cell development [50**]. EBF-activated targets (Cd79a, Gfra2 and pax5) gain the activation marks H3K9me and H3ac while EBF-repressed genes acquire repressive H3K27me3 marks. A subset of developmentally regulated genes (e.g., Cd40) exhibits the H3K4me2 poised mark at the pro B cell stage followed by the activating H3K4me3 and H3ac at the mature stage, suggesting that EBF primes chromatin prior to transcriptional activation. Enforced expression of EBF in a CD4+CD8+ T cell line or in NIH 3T3 cells reveals EBF capabilities for chromatin poising. In the T cell line, EBF binding and H3K4me2 modification is present at Cd79a, pax5 and Cd40 loci, with low-level transcription detectable from the Cd40 locus. In NIH3T3 cells, neither EBF binding nor activating histone marks are observed. Thus, EBF recognizes binding sites independent of transcriptional activation but not in closed chromatin [50**].

Busslinger et al. define the stepwise activation of the Pax5 locus. Pax5 expression is dictated by an enhancer in intron 5 of the pax5 locus and a promoter element [51**]. CpG motifs in the enhancer are demethylated during the HSC to MPP transition, and acquire the active chromatin mark H3K9ac+H3K27me3− by the pro B cell stage. The enhancer is positively activated by PU.1, IRF-4 and -8, and NFκB. By contrast, the promoter is demethylated even in HSCs. However, in the absence of E2A or EBF, the promoter fails to acquire the H3K9ac activating histone marks. These findings highlight a critical role for EBF in activation of the pax5 promoter.

Pax5 collaborates with other factors to remodel B lineage-specific targets mb-1 and Cd19. The mb-1 promoter undergoes demethylation during the HSC to pro B transition [52]. Demethylation requires the activity of both EBF and Pax5 as enforced expression of EBF in ebf−/−pax5−/− progenitors is not sufficient to mediate demethylation. Efficient transcription of mb-1 requires SWI/SNF activity and is suppressed by Mi-2NuRD chromatin remodeling complexes [52]. The CD19 locus undergoes stepwise activation of the enhancer and promoter [53]. E2A binding sites within the Cd19 enhancer are already demethylated as early as LSKs, suggesting that CD19 undergoes lineage priming well before the stage of lineage-specification. Progressive demethylation correlates with the successive binding of E2A, EBF and Pax5 in a developmental stage specific manner. CD19 transcriptional activation is achieved only after Pax5 binding to the promoter, an interaction accompanied by H3K4 trimethylation. Both studies detail the mechanistic importance of transcription factor cooperativity in lineage priming and the stable expression of B cell-specific genes, echoing a major theme of this Review.

Summary and Perspective

The ability to link coordinated changes in gene expression to developmental potential is essential for a clear vision of the mechanistic factors that drive lineage fate choice. Research progress over the last ten years has defined a core network of transcription factors that activate the B cell fate and repress alternative fates. We now add to this foundation an ability to discern the epigenomic marks that influence gene expression. The studies highlighted here describe epigenetic changes associated with HSC progression to the B cell fate at the hierarchical levels of genome-wide analysis, B lineage-specific transcription factor activation, and B cell locus-specific gene expression. On the horizon is the opportunity to evaluate chromatin poising and gene expression within single cells, the biological level at which lineage fate decisions are made. The most significant advances are likely to come from progenitors poised at critical developmental transitions. Observations that lineage priming within HSCs is associated with bivalent histone states raises major questions. On a per cell basis, do individual HSCs bearing identical bivalent marks have comparable potential for lineage progression? Or, are some HSCs refractory to lineage progression due to other limiting co-modifications? HSCs with heterogeneous development potential appear to co-exist in the bone marrow, with some stem cells expressing lymphoid bias, others expressing myeloid bias, and still others possessing a latent potential that manifests in robust repopulation activity only after secondary transplantation [54]. Future studies will reveal how chromatin status and gene expression patterns of individual HSCs – or cells representing later development stages – track with lineage reconstitution potential and progression to the B cell fate.

Acknowledgments

Supported by NIH R01 AI079047 with seed perspective developed under an NSF/Alfred P. Sloan Foundation Fellowship in Molecular Evolution (LB). We deeply appreciate direct input from K Murre, M Sigvardsson and K Medina.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Adolfsson J, Mansson R, Buza-Vidas N, Hultquist A, Liuba K, Jensen CT, Bryder D, Yang L, Borge OJ, Thoren LA, et al. Identification of Flt3+ lympho-myeloid stem cells lacking erythro-megakaryocytic potential a revised road map for adult blood lineage commitment. Cell. 2005;121:295–306. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Forsberg EC, Serwold T, Kogan S, Weissman IL, Passegue E. New evidence supporting megakaryocyte-erythrocyte potential of flk2/flt3+ multipotent hematopoietic progenitors. Cell. 2006;126:415–426. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hu M, Krause D, Greaves M, Sharkis S, Dexter M, Heyworth C, Enver T. Multilineage gene expression precedes commitment in the hemopoietic system. Genes Dev. 1997;11:774–785. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.6.774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mansson R, Hultquist A, Luc S, Yang L, Anderson K, Kharazi S, Al-Hashmi S, Liuba K, Thoren L, Adolfsson J, et al. Molecular evidence for hierarchical transcriptional lineage priming in fetal and adult stem cells and multipotent progenitors. Immunity. 2007;26:407–419. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spivakov M, Fisher AG. Epigenetic signatures of stem-cell identity. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8:263–271. doi: 10.1038/nrg2046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bernstein BE, Mikkelsen TS, Xie X, Kamal M, Huebert DJ, Cuff J, Fry B, Meissner A, Wernig M, Plath K, et al. A bivalent chromatin structure marks key developmental genes in embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2006;125:315–326. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7**.Weishaupt H, Sigvardsson M, Attema JL. Epigenetic chromatin states uniquely define the developmental plasticity of murine hematopoietic stem cells. Blood. 2010;115:247–256. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-07-235176. Mini-ChIP analysis of HSCs (CD150+ LSKs) reveals bivalent histone modification status of lineage-restricted promoters. ebf and pax5 have bivalent marks while Ikaros and pu.1 have only activating marks. Chromatin marks correlate with gene expression levels. Some promoters in splenic T cells bear bivalent marks raising the possibility of re-expression under select conditions (e.g. ccr9, normally expressed only in thymocytes). These data suggest one mechanism underlying developmental plasticity in “committed” cells (see reference 41) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Georgopoulos K, Bigby M, Wang JH, Molnar A, Wu P, Winandy S, Sharpe A. The Ikaros gene is required for the development of all lymphoid lineages. Cell. 1994;79:143–156. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90407-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9**.Ng SY, Yoshida T, Zhang J, Georgopoulos K. Genome-wide lineage-specific transcriptional networks underscore Ikaros-dependent lymphoid priming in hematopoietic stem cells. Immunity. 2009;30:493–507. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.01.014. Demonstrates requirement of Ikaros for repressing stem cell associated genes and inducing lympho-myeloid priming in HSCs (Flt3− LSKs). In contrast to previous models in which lymphoid priming was thought to be a relatively late event, HSC transcriptional signatures reveal lymphoid priming. Importantly, transcriptome analysis validated at the single cell level shows comparable frequency of lymphoid priming and erythroid priming, with a small proportion of HSCs exhibiting lymphoid/erythroid/myeloid co-priming. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thompson EC, Cobb BS, Sabbattini P, Meixlsperger S, Parelho V, Liberg D, Taylor B, Dillon N, Georgopoulos K, Jumaa H, et al. Ikaros DNA-binding proteins as integral components of B cell developmental-stage-specific regulatory circuits. Immunity. 2007;26:335–344. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11*.Reynaud D, Demarco IA, Reddy KL, Schjerven H, Bertolino E, Chen Z, Smale ST, Winandy S, Singh H. Regulation of B cell fate commitment and immunoglobulin heavy-chain gene rearrangements by Ikaros. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:927–936. doi: 10.1038/ni.1626. Defines B lineage specific roles of Ikaros. While forced expression of EBF in Ikaros-deficient MPPs produces CD19+, IL-7 responsive cells, these “pro-B” cells fail to undergo V(D)J recombination and still retain myeloid potential. Forced expression of Ikaros itself is required to induce rag expression, VH region accessibility, and IgH chromatin compaction. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spooner CJ, Cheng JX, Pujadas E, Laslo P, Singh H. A recurrent network involving the transcription factors PU.1 and Gfi1 orchestrates innate and adaptive immune cell fates. Immunity. 2009;31:576–586. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arinobu Y, Mizuno S, Chong Y, Shigematsu H, Iino T, Iwasaki H, Graf T, Mayfield R, Chan S, Kastner P, et al. Reciprocal activation of GATA-1 and PU.1 marks initial specification of hematopoietic stem cells into myeloerythroid and myelolymphoid lineages. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1:416–427. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DeKoter RP, Singh H. Regulation of B lymphocyte and macrophage development by graded expression of PU.1. Science. 2000;288:1439–1441. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5470.1439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nutt SL, Metcalf D, D’Amico A, Polli M, Wu L. Dynamic regulation of PU.1 expression in multipotent hematopoietic progenitors. J Exp Med. 2005;201:221–231. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.DeKoter RP, Lee HJ, Singh H. PU.1 regulates expression of the interleukin-7 receptor in lymphoid progenitors. Immunity. 2002;16:297–309. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00269-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.DeKoter RP, Walsh JC, Singh H. PU.1 regulates both cytokine-dependent proliferation and differentiation of granulocyte/macrophage progenitors. EMBO J. 1998;17:4456–4468. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.15.4456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li H, Ji M, Klarmann KD, Keller JR. Repression of Id2 expression by Gfi-1 is required for B-cell and myeloid development. Blood. 2010;116:1060–1069. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-11-255075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heinz S, Benner C, Spann N, Bertolino E, Lin YC, Laslo P, Cheng JX, Murre C, Singh H, Glass CK. Simple combinations of lineage-determining transcription factors prime cis-regulatory elements required for macrophage and B cell identities. Mol Cell. 2010;38:576–589. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20**.Dias S, Mansson R, Gurbuxani S, Sigvardsson M, Kee BL. E2A Proteins Promote Development of Lymphoid-Primed Multipotent Progenitors. Immunity. 2008;29:217–227. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.05.015. E2A is required for lymphoid lineage priming. E2A deficient mice have a paucity of Flt3hi LMPPs that fail to express lymphoid appropriate genes. This defect extends to HSCs, indicating a role for E2A in lymphoid priming even in stem cells (Flt3− LSKs). E2A is dispensable for megakaryocyte restriction but antagonizes LMPP differentiation to the myeloid fate. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Semerad CL, Mercer EM, Inlay MA, Weissman IL, Murre C. E2A proteins maintain the hematopoietic stem cell pool and promote the maturation of myelolymphoid and myeloerythroid progenitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:1930–1935. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808866106. E2A is required for HSC self-renewal. HSCs (CD150+Flt3− LSKs) lacking E2A fail to sustain hematopoiesis following serial adoptive transfer. E2A is mechanistically linked to the known regulators of HSC competence p21, p27 and mpl. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22**.Yang Q, Esplin BL, Borghesi L. E47 regulates hematopoietic stem cell proliferation and energetics but not myeloid lineage restriction. Blood. accepted pending minor revision 10/27/10. HSC --> MPP defect in E47 deficient mice is rescued by anti-oxidant treatment. E47-deficient HSCs (CD150+CD48− LSKs or Flt3− LSKs) within wild type hosts exhibit hyperproliferation and loss of p21. In vivo quantitative studies demonstrate that while long-term self-renewal and lymphoid repopulation activities are compromised, myeloid restriction remains intact. In vivo treatment with antioxidant restores numbers of MPPs in E47 knockout mice. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang Q, Kardava L, St Leger A, Martincic K, Varnum-Finney B, Bernstein ID, Milcarek C, Borghesi L. E47 controls the developmental integrity and cell cycle quiescence of multipotential hematopoietic progenitors. J Immunol. 2008;181:5885–5894. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.9.5885. E47 is required for HSC proliferative integrity. HSCs (defined as CD150+CD48− LSKs, CD27− LSKs or Flt3− LSKs) lacking E47 exhibit hyperproliferation, and fail to produce a robust MPP compartment. p21 is identified as a direct E47 target gene. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Perry SS, Zhao Y, Nie L, Cochrane SW, Huang Z, Sun XH. Id1, but not Id3, directs long-term repopulating hematopoietic stem-cell maintenance. Blood. 2007;110:2351–2360. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-01-069914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Suh HC, Ji M, Gooya J, Lee M, Klarmann KD, Keller JR. Cell-nonautonomous function of Id1 in the hematopoietic progenitor cell niche. Blood. 2009;114:1186–1195. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-09-179788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lacombe J, Herblot S, Rojas-Sutterlin S, Haman A, Barakat S, Iscove NN, Sauvageau G, Hoang T. Scl regulates the quiescence and the long-term competence of hematopoietic stem cells. Blood. 2010;115:792–803. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-01-201384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Borghesi L, Aites J, Nelson S, Lefterov P, James P, Gerstein R. E47 is required for V(D)J recombinase activity in common lymphoid progenitors. J Exp Med. 2005;202:1669–1677. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cochrane SW, Zhao Y, Welner RS, Sun XH. Balance between Id and E proteins regulates myeloid-versus-lymphoid lineage decisions. Blood. 2009;113:1016–1026. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-06-164996. Targeted manipulation of E protein or Id protein activity directs lineage fate choice in LMPPs. Id-1 is expressed in HSCs, is turned off during MEP and CMP restriction, and is re-expressed in myeloid cells. Forced expression of Id1 in LSKs favors myeloid over lymphoid development. Expression of a cre inducible dominant negative inhibitor of Id activity has the reverse effect with LSKs and LMPPs showing robust lymphoid over myeloid production. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lai AY, Watanabe A, O’Brien T, Kondo M. Pertussis toxin-sensitive G proteins regulate lymphoid lineage specification in multipotent hematopoietic progenitors. Blood. 2009;113:5757–5764. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-01-201939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gwin K, Frank E, Bossou A, Medina KL. Hoxa9 Regulates Flt3 in Lymphohematopoietic Progenitors. J Immunol. 2010 doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0904203. in press for 01 December. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhuang Y, Soriano P, Weintraub H. The helix-loop-helix gene E2A is required for B cell formation. Cell. 1994;79:875–884. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90076-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang D, Claus CL, Rajkumar P, Braunstein M, Moore AJ, Sigvardsson M, Anderson MK. Context-Dependent Regulation of Hematopoietic Lineage Choice by HEBAlt. J Immunol. 185:4109–4117. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901783. Defines biological role for Alt (alternative) splice form of HEB. Forced expression of HEBalt in uncommitted fetal liver progenitors blocks E2A activity thereby favoring myeloid over B cell outgrowth. In combination with Notch signals, HEBalt favors T over myeloid outgrowth. HEBcan (canonical) does not suppress myeloid potential. These data demonstrate a unique function of the Alt domain as a context-dependent regulator of lineage fate choice. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pongubala JM, Northrup DL, Lancki DW, Medina KL, Treiber T, Bertolino E, Thomas M, Grosschedl R, Allman D, Singh H. Transcription factor EBF restricts alternative lineage options and promotes B cell fate commitment independently of Pax5. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:203–215. doi: 10.1038/ni1555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang H, Lee CH, Qi C, Tailor P, Feng J, Abbasi S, Atsumi T, Morse HC., 3rd IRF8 regulates B-cell lineage specification, commitment, and differentiation. Blood. 2008;112:4028–4038. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-01-129049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thal MA, Carvalho TL, He T, Kim HG, Gao H, Hagman J, Klug CA. Ebf1-mediated down-regulation of Id2 and Id3 is essential for specification of the B cell lineage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:552–557. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802550106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zandi S, Mansson R, Tsapogas P, Zetterblad J, Bryder D, Sigvardsson M. EBF1 is essential for B-lineage priming and establishment of a transcription factor network in common lymphoid progenitors. J Immunol. 2008;181:3364–3372. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.5.3364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37**.Mansson R, Zandi S, Welinder E, Tsapogas P, Sakaguchi N, Bryder D, Sigvardsson M. Single-cell analysis of the common lymphoid progenitor compartment reveals functional and molecular heterogeneity. Blood. 2010;115:2601–2609. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-08-236398. The CLP compartment is populated by progenitors subsets with constrained lineage potential as opposed to a uniform population of multipotent progenitors. This study tracks lineage fate potential of single CLPs using the dual molecular tracers rag1 (indicator of lymphoid lineage progression) expression and the λ5 light chain gene (reflects Pax5 transcriptional activity). Raglo cells retain B, T and NK potential while raghi cells have B and T potential. Within raghi CLPs, only the λ5+ subset is B lineage restricted. These data suggest that inhibition of NK potential depends on EBF but not Pax5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38*.Welner RS, Esplin BL, Garrett KP, Pelayo R, Luche H, Fehling HJ, Kincade PW. Asynchronous RAG-1 expression during B lymphopoiesis. J Immunol. 2009;183:7768–7777. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902333. Fate mapping study of Rag1+ progenitors using a permanent red fluorescence tagging. Rag1/Red+ CLPs progress more quickly to the CD19+ stage as compared to their Rag1/Red− counterparts. Following exposure to TLR ligands, Rag1/Red+ CLPs are lineage stable and efficiently give rise to CD19+ cells while Rag1/Red− CLPs generate DC and NK cells with a near complete inhibition of B cell potential. Thus, bone marrow progenitors become increasingly committed to the B lineage concordant with Rag expression. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39*.Inlay MA, Bhattacharya D, Sahoo D, Serwold T, Seita J, Karsunky H, Plevritis SK, Dill DL, Weissman IL. Ly6d marks the earliest stage of B-cell specification and identifies the branchpoint between B-cell and T-cell development. Genes Dev. 2009;23:2376–2381. doi: 10.1101/gad.1836009. Uses the algorithm MidReg to identify Ly6D as a surface marker that phenotypically resolves CLPs with lymphoid potential versus CLPs that are B lymphoid progenitors. Ly6D− CLPs have low IL7Rα expression and retain T, NK and DC potential that is lost upon Ly6D expression. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lukin K, Fields S, Lopez D, Cherrier M, Ternyak K, Ramirez J, Feeney AJ, Hagman J. Compound haploinsufficiencies of Ebf1 and Runx1 genes impede B cell lineage progression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:7869–7874. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003525107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41**.Cobaleda C, Jochum W, Busslinger M. Conversion of mature B cells into T cells by dedifferentiation to uncommitted progenitors. Nature. 2007;449:473–477. doi: 10.1038/nature06159. Landmark publication demonstrating conversion of splenic B cells into functional T cells by conditional deletion of a single factor. Targeted ablation of pax5 in splenic B cells leads to loss of surface immunoglobulin and re-expression of immature cell surface markers. Following adoptive transfer into T cell deficient mice, these former B cells, permanently marked at the genetic level by historic immunoglobulin gene rearrangements, produce TCR+ T cells that provide competent T cell help following antigen challenge. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mathas S, Janz M, Hummel F, Hummel M, Wollert-Wulf B, Lusatis S, Anagnostopoulos I, Lietz A, Sigvardsson M, Jundt F, et al. Intrinsic inhibition of transcription factor E2A by HLH proteins ABF-1 and Id2 mediates reprogramming of neoplastic B cells in Hodgkin lymphoma. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:207–215. doi: 10.1038/ni1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mohtashami M, Shah DK, Nakase H, Kianizad K, Petrie HT, Zuniga-Pflucker JC. Direct comparison of Dll1- and Dll4-mediated Notch activation levels shows differential lymphomyeloid lineage commitment outcomes. J Immunol. 2010;185:867–876. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44**.Lin YC, Jhunjhunwala S, Benner C, Heinz S, Welinder E, Mansson R, Sigvardsson M, Hagman J, Espinoza CA, Dutkowski J, et al. A global network of transcription factors, involving E2A, EBF1 and Foxo1, that orchestrates B cell fate. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:635–643. doi: 10.1038/ni.1891. Integrates transcriptional regulators, epigenetic modifications, and the expression of lineage specific genes at a defined developmental transition in B cells. E2A occupancy at cis regulatory regions is associated with activating H3K4 modifications. The pre-pro-B to pro-B transition is marked differential patterns of E2A binding and H3K4 methylation including the acquisition of appreciable new binding sites in pro-B cells. E2A sites are enriched for cis regulatory sequences associated with candidate cooperative factors, and coordinate occupancy of cis elements by E2A, EBF and Foxo1 correlates with quantitative increases in expression of B lymphoid genes. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dengler HS, Baracho GV, Omori SA, Bruckner S, Arden KC, Castrillon DH, DePinho RA, Rickert RC. Distinct functions for the transcription factor Foxo1 at various stages of B cell differentiation. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:1388–1398. doi: 10.1038/ni.1667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Amin RH, Schlissel MS. Foxo1 directly regulates the transcription of recombination-activating genes during B cell development. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:613–622. doi: 10.1038/ni.1612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Degner SC, Wong TP, Jankevicius G, Feeney AJ. Cutting edge: developmental stage-specific recruitment of cohesin to CTCF sites throughout immunoglobulin loci during B lymphocyte development. J Immunol. 2009;182:44–48. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.1.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu P, Keller JR, Ortiz M, Tessarollo L, Rachel RA, Nakamura T, Jenkins NA, Copeland NG. Bcl11a is essential for normal lymphoid development. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:525–532. doi: 10.1038/ni925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.O’Riordan M, Grosschedl R. Coordinate regulation of B cell differentiation by the transcription factors EBF and E2A. Immunity. 1999;11:21–31. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80078-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50**.Treiber T, Mandel EM, Pott S, Gyory I, Firner S, Liu ET, Grosschedl R. Early B cell factor 1 regulates B cell gene networks by activation, repression, and transcription- independent poising of chromatin. Immunity. 2010;32:714–725. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.04.013. EBF remodels chromatin independent of transcription activation. Genome wide ChiP analysis defines EBF binding sites, many of which overlap with E2A and RUNX. EBF binding correlates with transcript expression, particularly of genes associated with B cell receptor signaling. Forced expression of EBF in a T cell line leads to EBF binding to genomic regions, H3K4 dimethylation of B cell specific genes, and low level transcriptional activation of CD40. Parallel experiments on NIH3T3 cells demonstrated no substantial binding of EBF. Thus, EBF activates lineage-specific genes in the context of hematopoietic chromatin but not closed chromatin. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51**.Decker T, Pasca di Magliano M, McManus S, Sun Q, Bonifer C, Tagoh H, Busslinger M. Stepwise activation of enhancer and promoter regions of the B cell commitment gene Pax5 in early lymphopoiesis. Immunity. 2009;30:508–520. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.01.012. Deletion mapping and epigenetic status of pax5 regulatory elements reveals stepwise epigenetic activation. The pax5 enhancer and promoter are differentially controlled by CpG methylation and chromatin marks. The enhancer is subject to developmental stage specific demethylation while the promoter remains unmethylated even in HSCs. Conversely, the enhancer bears activation marks (H3K9ac) in the absence of E2A and EBF while the promoter is repressed (H3K9ac−H3K27+) under these same circumstances. Functional binding sites for PU.1, IRF4, IRF8 and NFκB further regulate enhancer activity. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gao H, Lukin K, Ramirez J, Fields S, Lopez D, Hagman J. Opposing effects of SWI/SNF and Mi-2/NuRD chromatin remodeling complexes on epigenetic reprogramming by EBF and Pax5. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:11258–11263. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809485106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Walter K, Bonifer C, Tagoh H. Stem cell-specific epigenetic priming and B cell-specific transcriptional activation at the mouse Cd19 locus. Blood. 2008;112:1673–1682. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-02-142786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hock H. Some hematopoietic stem cells are more equal than others. J Exp Med. 2010;207:1127–1130. doi: 10.1084/jem.20100950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]