Abstract

The vaccinia virus entry-fusion complex (EFC) consists of 10 to 12 proteins that are embedded in the viral membrane and individually required for fusion with the cell and entry of the core into the cytoplasm. The architecture of the EFC is unknown except for information regarding two pair-wise interactions: A28 with H2 and A16 with G9. Here we used a technique to destabilize the EFC by repressing the expression of individual components and identified a third pair-wise interaction: G3 with L5. These two proteins remained associated under several different EFC destabilization conditions and in each case were immunopurified together as demonstrated by Western blotting. Further evidence for the specific interaction of G3 and L5 was obtained by mass spectrometry. This interaction also occurred when G3 and L5 were expressed in uninfected cells, indicating that no other viral proteins were required. Thus, the present study extends our knowledge of the protein interactions important for EFC assembly and stability.

Keywords: Poxvirus, Protein interactions, Multisubunit complex, Immunopurification, Mass spectrometry

Introduction

Poxviruses, of which vaccinia virus (VACV) is the prototype, are distinguished by their large size and cytoplasmic site of transcription, DNA replication and virion assembly (Moss, 2007). The major infectious form of VACV, the mature virion (MV), has a nucleoprotein core comprised of a 195-kbp dsDNA genome and 50 or more proteins (Chung et al., 2006; Resch et al., 2007; Yoder et al., 2006). Surrounding the core is a lipid membrane with about 25 associated proteins. Several of the latter have overlapping or redundant roles in mediating the binding of the MV to the host cell. A27, H3, and D8 associate with glycosaminoglycans on the cell surface and A26 binds to laminin (Chiu et al., 2007; Chung et al., 1998; Hsiao, Chung, and Chang, 1999; Lin et al., 2000). The L1 protein has also been suggested to have a role in binding, although no receptor has been identified (Foo et al., 2009).

A large number of proteins have been implicated in the membrane fusion step, creating a pore for entry of the core into the cytoplasm (Moss, 2006). Using genetic and biochemical methods, 12 such proteins were identified: A16 (Ojeda, Senkevich, and Moss, 2006), A21 (Townsley, Senkevich, and Moss, 2005), A28 (Senkevich, Ward, and Moss, 2004), F9 (Brown, Senkevich, and Moss, 2006), G3 (Izmailyan et al., 2006), G9 (Ojeda, Domi, and Moss, 2006), H2 (Senkevich and Moss, 2005), I2 (Nichols et al., 2008), J5 (Senkevich et al., 2005), L1 (Bisht, Weisberg, and Moss, 2008), L5 (Townsley, Senkevich, and Moss, 2005) and O3 (Satheshkumar and Moss, 2009). Each one, except J5, has been shown to be individually required for entry and except for I2, the proteins have been shown to associate as a complex. Nine of these proteins (A16, A21, A28, G3, G9, H2, J5, L5, and O3) have been designated as integral components of the entry-fusion complex (EFC) because absence of any one results in the destabilization of the complex. L1 and F9 are also associated with the complex but are not required for EFC assembly or stability, suggesting that they may be associated peripherally.

Very little is known about the architecture of the EFC and even less is known about the specific roles of EFC proteins in virus entry. Previous studies indicated that the proteins of the EFC traffic independently to the viral membrane yet the complex seems to be held together by multiple interactions since the absence of single components destabilize the EFC in the presence of Triton X-100 (Senkevich et al., 2005). The latter observation has provided a way to identify pair-wise protein interactions that persist under destabilization conditions. With this approach, interactions between H2 and A28 (Nelson, Wagenaar, and Moss, 2008) and between G9 and A16 (Wagenaar, Ojeda, and Moss, 2008) were discovered and confirmed by transfection studies in uninfected cells. The present study extends our knowledge of the protein interactions important for EFC assembly and stability. Using the EFC destabilization approach in infected cells and coexpression in uninfected cells, we obtained evidence for direct association of the G3 and L5 proteins.

Results and Discussion

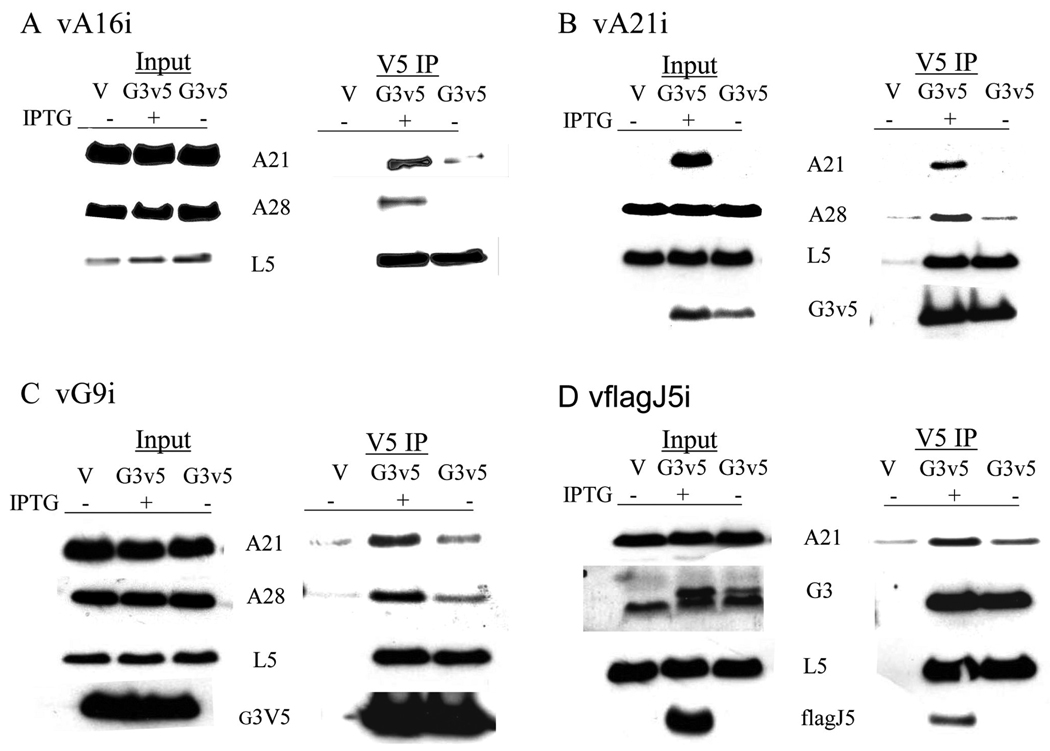

G3 and L5 remained associated when the entry fusion complex was destabilized

We implemented the EFC destabilization approach by attempting to determine which if any proteins remained associated with G3 under such conditions. Human 293TT cells were infected with several different inducible recombinant viruses in the presence or absence of isopropylthiogalactoside (IPTG) and transfected with a plasmid encoding a V5 epitope-tagged G3 protein or an empty vector. After 24 h at 37°C, the cells were harvested and lysed with 1% Triton X-100. Following a brief centrifugation, the post-nuclear supernatants were analyzed by Western blotting either directly (Input) or after immunoaffinity purification (IP) with anti-V5 agarose. Analysis of the Input confirmed that the inducible genes of the VACV recombinants vA16i, vA21i, vJ5i, and vG9i were severely repressed in the absence of IPTG, whereas the other EFC proteins analyzed were expressed (Fig. 1 and data not shown). In addition, representative EFC proteins expressed in the presence of IPTG copurified with the V5-tagged G3 protein, indicating that the latter was incorporated into the stable complex (Fig. 1). We compared the relative amounts of the EFC proteins that copurified with G3V5 in the presence and absence of IPTG. In each condition, the intensity of the L5 band was similar whereas other EFC proteins only associated strongly with G3V5 in the presence of IPTG. The association of L5 with G3 was specific since L5 was not detected after IP when the vector plasmid was transfected (Fig. 1).

Fig 1. IP of L5 with G3V5 under EFC destabilization conditions.

Human 293TT cells were infected with the following viruses in the presence (+) and absence (−) of IPTG: (A) A16i, (B) A21i, (C) G9i, or (D) vflagJ5i and transfected with vector alone (V) or vector encoding G3V5. The Triton X-100 soluble fraction of infected cells was analyzed by Western blotting before (Input) or after (V5 IP) IP with anti-V5 beads. Antibodies to A16, A21, A28, G3, G9, L5, flag and V5 were used for probing the blot as indicated.

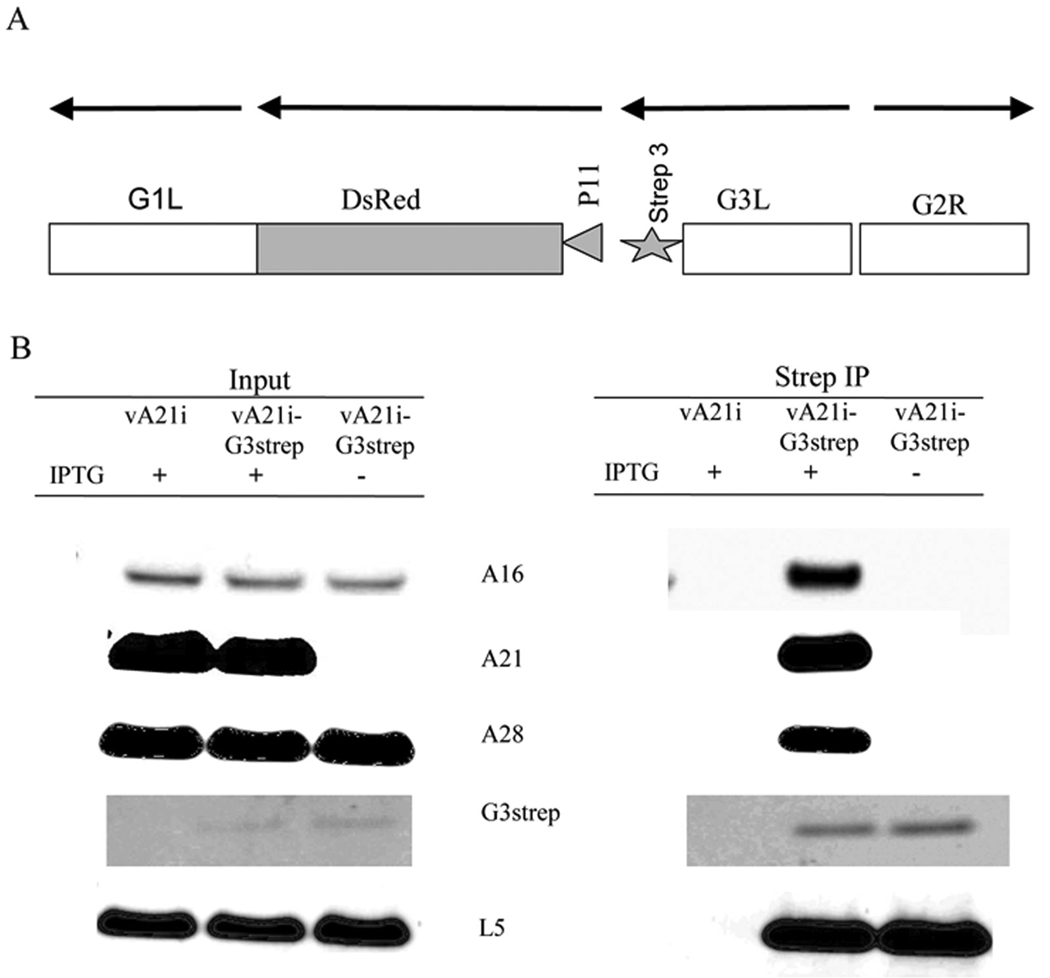

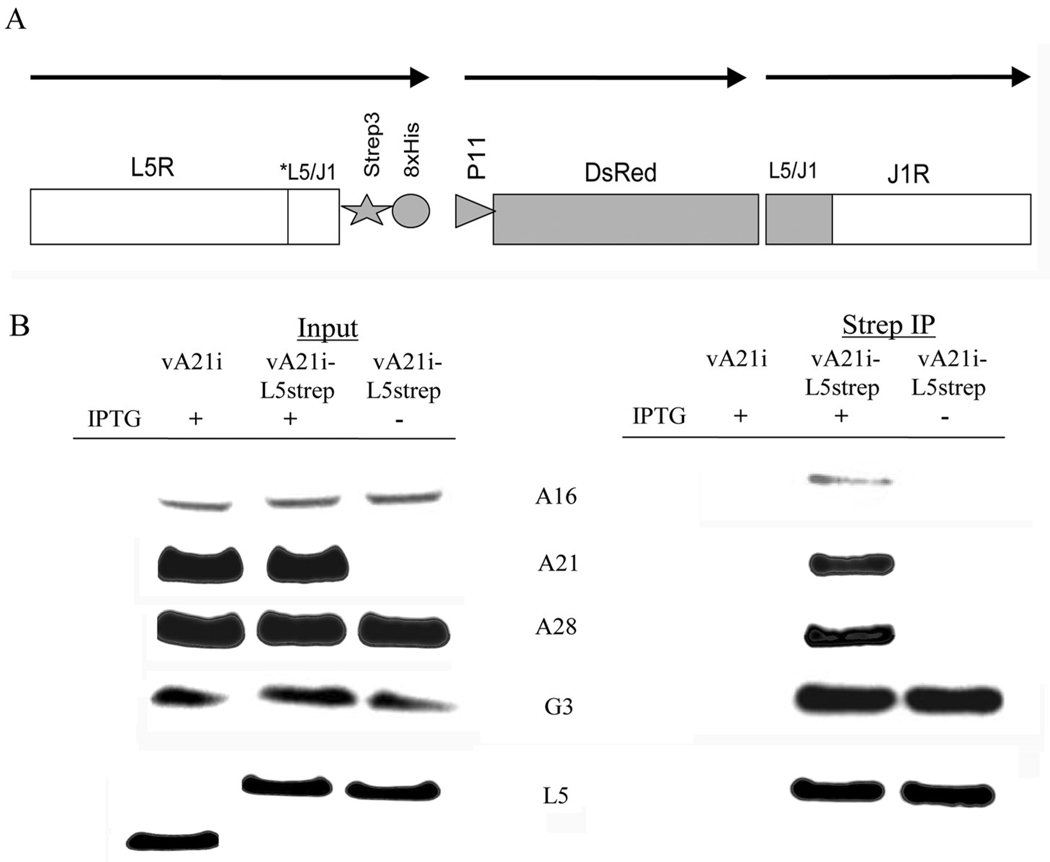

To confirm the interaction between G3 and L5, we made recombinant VACVs with an inducible A21 gene that also expressed either C-terminal strep-tagged G3 or strep-8xhis-tagged L5 (Fig. 2A, 3A). Use of these recombinant viruses had advantages over the above infection/transfection protocol: (i) untagged copies of G3 and L5 were not present to compete with the tagged version; (ii) scale up was simpler as transfection was not needed. BS-C-1 cells were infected with vA21i as a control or vA21iG3strep with or without IPTG. After 24 h, the cells were harvested, lysed with Triton X-100, clarified and allowed to bind to strepactin beads. The bound proteins were eluted with biotin and analyzed by Western blotting. In the presence of IPTG, A16, A21, A28 and L5 copurified with G3strep indicating the presence of a stable complex, whereas only L5 copurified with G3 strep in the absence of IPTG (Fig. 2B). Similarly, cells were infected with vA21i as a control or vA21iL5strep-8xhis with or without IPTG. A16, A21, A28 and G3 copurified with L5strep-8xhis in the presence of IPTG but only G3 copurified with L5strep-8xhis in the absence of IPTG (Fig. 3B). These data provided further evidence for an interaction between G3 and L5.

Fig 2. IP of L5 with G3strep under EFC destabilization conditions.

(A) Diagram of G3strep recombinant DNA inserted into vA21i. Arrows over the ORFs indicate the direction of transcription. The construct includes the G3L ORF encoding a C-terminal Strep3 tag under the control of the native G3L promoter, a copy of the DsRed ORF under the control of the VACV P11 late promoter, and VACV flanking sequences to allow homologous recombination. (B) Human 293TT cells were infected with vA21i or vA21iG3strep in the presence (+) and absence (−) of IPTG. Triton X-100 soluble extracts were analyzed by Western blotting before (Input) and after strep IP with streptactin beads. Antibodies to A21, A28, G3 and L5 were detected by fluorescence. Antibody to A16 was detected by chemiluminescence.

Fig 3. IP of G3 with L5strep-8xhis under EFC destabilization conditions.

(A) Diagram of L5strep-8xhis recombinant DNA inserted into vA21i. Arrows over ORFs indicate the direction of transcription. The construct includes the L5R ORF encoding a C-terminal strep tag followed by 8xhis tag under the control of the native L5R promoter, a copy of the DsRed ORF under the control of the VACV P11 late promoter and VACV flanking sequences to allow homologous recombination. Note: Because of overlap between the downstream ORF of L5 and the upstream ORF of J1 this region (L5/J1) was duplicated in the construct to allow addition of the strep-8xhis tag to the carboxy terminus of L5. Silent mutations were also incorporated in L5/J1 region to prevent instability of the genome due to repeat DNA sequences. (B) Human 293TT cells were infected with vA21i or vA21iL5strep-8xhis (abbreviated vA21iL5strep) in the presence (+) and absence (−) of IPTG. Triton X-100 soluble extracts were analyzed by Western blotting before (Input) and after strep IP with streptactin beads. Antibodies to A21, A28, and L5 were detected by fluorescence. Antibodies to A16 and G3 were detected by chemiluminescence.

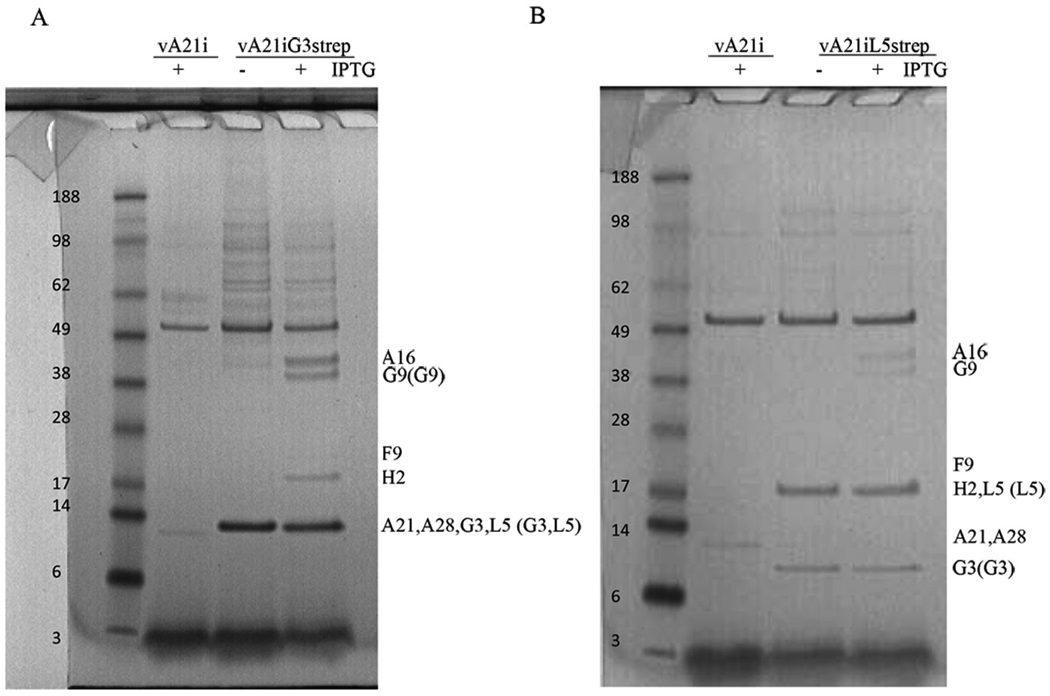

Detection of the interaction between G3 and L5 by mass spectrometry

The above data provided evidence for an interaction between G3 and L5, though not necessarily direct as we could not screen for all of the EFC proteins because antibodies to some were not available or not useful because of low affinity or poor specificity. Mass spectrometry was used as an alternative to Western blotting in order to confirm the interaction of G3 and L5 and determine whether any other proteins were associated with them under EFC destabilization conditions. BS-C-1 cells were infected with vA21i as a control or vA21iG3strep or vA21iL5strep-8xhis with or without IPTG as in the preceding section. However, after elution from streptactin beads, the proteins were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and stained with Coomassie blue. Visible protein bands from the vA21iG3strep (+IPTG) and vA21iL5strep-8xhis (+IPTG) lanes were excised for identification by mass spectrometry. Corresponding regions from lanes loaded with proteins from cells infected with vA21i in the presence of IPTG and from cells infected with vA21iG3strep and vA21iL5strep-8xhis in the absence of IPTG were also excised for protein identification. When IPTG was present and A21 was expressed in cells infected with vA21iG3strep, mass spectrometry analysis indicated that A16, G9, F9, H2, A21, A28, L5 and G3 had bound and were eluted together from streptactin-beads. Only G9, L5 and G3 were detected, however, when A21 expression was repressed by omission of IPTG in vA21iG3strep infected cells (Fig. 4A, Table 1). When cells were infected with vA21iL5strep-8xhis under conditions in which A21 was expressed, EFC proteins A16, G9, F9, H2, A21, A28, and G3 copurified with L5 strep on streptactin-beads. Only L5 and G3 were detected when A21was not expressed (Fig. 4B, Table 1). These data confirmed the interaction of G3 and L5 and also suggested an interaction with G9. However, G9 is not required for the interaction of G3 and L5 as shown in Fig. 1. No other EFC proteins were detected in association with G3 or L5 under destabilizing conditions. However, we cannot exclude an interaction with I2 and O3, which have not been detected by mass spectroscopy either in this experiment or in others probably because of their small size and hydrophobicity, or with J5, which was not detected in the +IPTG control.

Fig 4. Identification by mass spectrometry of EFC proteins associated with G3strep and L5strep-8xhis in the absence of A21.

(A) BS-C-1 cells were infected with vA21i or vA21iG3strep with (+) or without (−) IPTG. Infected cells were harvested after 24 h and lysed in 1% triton X-100. After a brief centrifugation the postnuclear supernatant was incubated with streptactin-beads for 3.5 h. Bound protein was eluted with biotin and separated by SDS-PAGE. Protein bands stained with Coomassie blue are shown with the positions of mass marker proteins in kDa on the left. The numbers on the right are the names of proteins that copurified with G3strep as determined by mass spectrometry.

Those in parentheses copurified in the absence of A21 expression. Note that multiple proteins comigrated under these conditions and some bands are faint. (B) BS-C-1 cells were infected with vA21i or vA21iL5strep-8xhis (abbreviated vA21iL5strep) with (+) or without (−) IPTG and analyzed as in panel A.

TABLE 1.

Identification of EFC proteins copurifying with G3Strep and L5strep-8xhisa

| vA21i (+IPTG) |

vA21iG3strep (+IPTG) |

vA21iG3str ep (−IPTG) |

vA21iL5strepb (+IPTG) |

vA21iL5strepb (−IPTG) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G3 | - | 5 | 4 | 6 | 5 |

| L5 | - | 6 | 3 | 6 | 5 |

| A28 | - | 3 | - | 2 | - |

| A21 | - | 2 | - | 1 | - |

| H2 | - | 8 | - | 4 | - |

| F9 | - | 6 | - | 2 | - |

| G9 | - | 12 | 4 | 4 | - |

| A16 | - | 13 | - | 11 | - |

The number of peptides for each EFC protein identified by mass spectrometry is listed.

vA21iL5strep-8xhis is abbreviated as vA21iL5strep

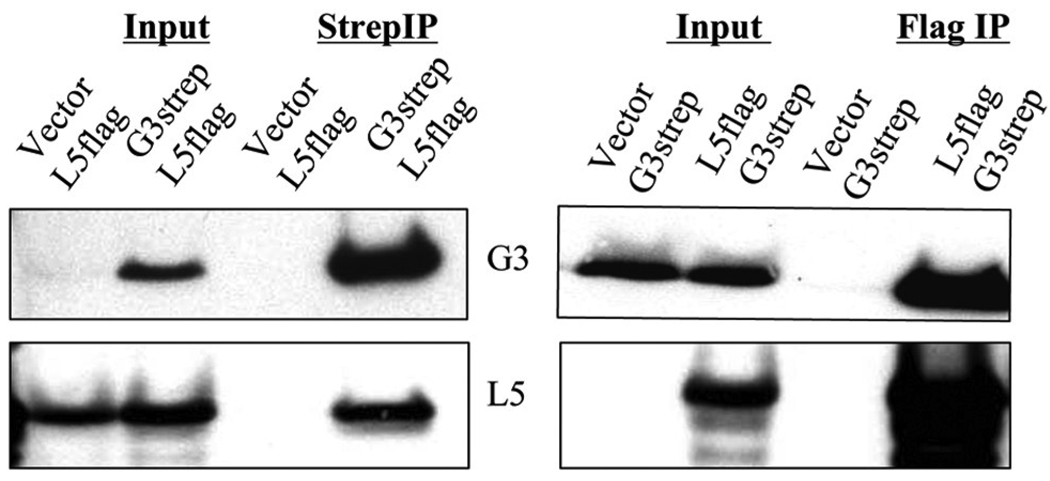

G3 interacts specifically with L5 in the absence of other viral proteins

To provide further evidence for a direct interaction between G3 and L5, we expressed the proteins in uninfected human 293TT cells. The G3 and L5 open reading frames (ORFs) were codon optimized for expression in human cells and tagged with strep and 3Xflag epitopes, respectively. In addition, since the EFC proteins are not glycosylated in the viral membrane, a potential N-glycosylation site in L5 was removed by an S117A replacement. The modified G3strep and L5flag ORFs were cloned into separate plasmid vectors under the control of the cytomegalovirus early promoter. Human 293TT cells were transfected with G3strep and L5flag plasmids separately or together. After 48 h, the cells were lysed with Triton X-100 detergent, and the post nuclear supernatants were incubated with either anti-flag agarose or streptactin-beads. The proteins in the postnuclear supernatant and eluate fractions were resolved by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blotting. The G3 antibody was able to detect G3strep eluted from anti-flag agarose only when co-expressed with L5flag (Fig. 5A). Reciprocally, the L5 antibody was only able to detect L5flag eluted from streptactin-beads when it was co-expressed with G3strep (Fig. 5B). We concluded that the interaction between G3 and L5 was stable and did not require other viral proteins.

Fig 5. Interaction between G3 and L5 in uninfected cells.

(A) Cells were cotransfected with the plasmid encoding L5flag and either the empty vector or the plasmid expressing G3strep. The postnuclear supernatant (Input) and affinity bound proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting with antibody to G3 or L5. (B) Cells were cotransfected with the plasmid encoding G3strep and either the empty vector or the plasmid expressing L5flag. The postnuclear supernatant (Input) and affinity bound proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting with antibody to G3 or L5.

Conclusions

Previous studies had shown pair-wise interactions between the A28 and H2 and between the A16 and G9 components of the EFC. The purpose of the present study was to determine the interaction partner(s) of the G3 protein. We found by IP and Western blotting that G3 and L5 interact under conditions in which the EFC is destabilized by repression of A16, A21, A28, G9 or J5. This result was confirmed in several ways. First, we made recombinant viruses in which expression of A21 was repressed and either G3 or L5 was epitope-tagged and then demonstrated the interaction by IP followed by Western blotting and mass spectrometry. Mass spectrometry also identified G9 in association with G3, suggesting an additional interaction that needs to be verified by further experiments including the construction of additional recombinant viruses. However, G3 and L5 were still associated when G9 was repressed indicating that the latter does not mediate G3 and L5 interactions. Further evidence for the interaction of G3 and L5 was obtained by their expression in uninfected cells, indicating that no other viral proteins are required. At present we are exploring additional methods of determining the architecture of the EFC.

Materials and Methods

Cells and viruses

BS-C-1 cells were grown in minimum essential medium with Earl’s balanced salts (Quality Biological, Gaithersburg, MD) supplemented with 2 mM L-Gln and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Human 293TT cells were grown in Dulbecco minimum essential medium (DMEM: Quality Biological) supplemented with 10% FBS, 2 mM L-Gln. The Western Reserve (WR) strain of vaccinia virus (ATCC VR-1354; accession number AY243312) was used in the construction of plasmids expressing EFC proteins and recombinant viruses. The general procedures for preparing and titrating virus stocks were described previously (Earl et al., 1998a; Earl and Moss, 1998).

Expression plasmids

For expression of G3V5 protein in VACV-infected cells, the G3L promotor and ORF were amplified by PCR (Accuprime PFX, Invitrogen) using the genomic DNA of VACV as a template. The forward primer for G3L amplification hybridized at 64 bp upstream of the G3L ORF. The coding sequence for the V5 tag was included at the 5’ end of the reverse primer. The structures were verified by DNA sequencing.

For expression of the VACV proteins G3 and L5 in uninfected cells, their DNA sequences were optimized (Geneart, Regensburg, Germany) to alter codon usage and G-C content to improve RNA processing and translation. A potential glycosylation site in L5 was removed by a S115A mutation. These DNA sequences were amplified by PCR with one primer also coding for the appropriate epitope tag and then inserted into pcDNA3.3 vector (Invitrogen) under the control of the early cytomegalovirus promotor. In that way the following plasmids were constructed: L5flag (3xflag epitope appended to C terminal end); G3strep (StrepIII tag: WSHPQFEKGGGSGGGSGGGSWSHPQFEK) appended to C terminal end (Schmidt and Skerra, 2007).

Recombinant VACV construction

Recombinant viruses vA21iG3strep and vA21iL5strep-8xhis were modified from vA21i (Townsley, Senkevich, and Moss, 2005) by the insertion of DNA encoding Discosoma sp. DsRed fluorescent protein and appending the strepIII tag sequence and StrepIII-8his tag sequence to the 3’ ends of the G3L and L5R ORFs, respectively. (Notation: “v” refers to virus; “i” indicates inducible gene; and strep indicates strepIII tag at the 3’ end of the ORF.) Overlapping PCR (Accuprime Pfx; Invitrogen) was used to assemble the DNA constructs for subsequent virus recombination. Following PCR, the construct was cloned into pCR-Blunt II-TOPO (Invitrogen) and verified by DNA sequencing. vA21i infected BS-C-1 cells were transfected with linearized G3strep or L5strep-8xhis recombinant DNA using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). IPTG (100 µm) was added to the medium to induce expression of the A21i gene. Recombinant virus was identified by red fluorescence and clonally purified during several rounds of plaque isolation as described previously (Earl et al., 1998b).

The DNA arrangement from the 5’ to the 3’ end of the linearized G3strep recombinant DNA was as follows: 1) begins 500 bp from the 5’ end of the G1L ORF continuing 45 bp upstream of the G1L ORF, 2) red fluorescent protein (DsRed) ORF expressed from p11, a VACV late promoter, 3) G3L ORF with strepIII tag appended to the C terminus and continuing 200 bp upstream of the G3L ORF.

The DNA sequence from the 5’ to the 3’ end of the linearized L5strep-8xhis construct was as follows: 1) begins 233 bp upstream of the L5R ORF with the strepIII tag followed by the 8xhis tag appended to 3’end of the L5R ORF, 2) red fluorescent protein (DsRed) ORF expressed from p11, 3) duplication of the L5/J1 overlapping region beginning 91 bp upstream of the 3’ end of L5R ORF and extending through the J1 ORF to 48 bp past the 3’ end. Duplication of L5/J1 overlapping region allowed normal expression of J1 as it includes the J1 promoter. Silent mutations were introduced into the 3’ end of L5 ORF (L5/J1 overlap region) to avoid direct repeats, which are unstable in the VACV genome.

Affinity purification

Two roller bottles with BS-C-1 cells were infected for 2 h with 5 PFU per cell of vA21i or vA21iG3strep in the presence of 100 µM IPTG or 10 PFU of vA21iG3strep in the absence of IPTG. After removal of the virus inoculum, 150 ml of EMEM (2.5% FBS, 2 mM Gln) was added to each roller bottle. After 24 h, the cells were harvested and lysed for 1 h at 4°C with rotation in 2 ml of 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer (PBS) (pH 8.0), 0.2 M NaCl, 1% Triton X, 100 µg/ml avidin, and protease inhibitors: phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis), N-ethylmaleimide (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis), and EDTA free complete protease inhibitor cocktail tablet (Roche, Indianapolis). The debris was removed by centrifugation for 10 min at 10,600 × g. The lysate was incubated with 50 µl streptactin beads (IBA, Gottingen, Germany) on a rotator for 4 h. The supernatant was removed after 30-sec centrifugation at 6,000 × g. The beads were washed four times by centrifuging after incubating in lysis buffer for 3 min. The final wash was with lysis buffer without Triton X-100. Bound protein was eluted with a 3-min incubation with (IBA, Gottingen, Germany) biotin elution buffer (50 µl) followed by brief centrifugation. Elution was repeated with 100 µl of biotin elution buffer. The eluates were combined, concentrated and separated by SDS-PAGE. The gel was stained with Coomassie blue, proteins bands were cut from the gel, digested with trypsin and analyzed by mass spectrometry by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases core facility.

Immunoaffinity purification

For transfection of uninfected cells, one T150 flask of 293TT cells in DMEM, 10% FBS, 2 mM Gln were transfected with 30 µg of plasmid preincubated with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). After 24 h, fresh DMEM, 10% FBS, 2 mM Gln was added and the cells were harvested after an additional 24 h.

For combined infection and transfection experiments, one T150 flask plated with 293TT cells were infected with 3 to 5 PFU per cell in DMEM with 2.5% FBS, 2 mM Gln for 1 h at 37C. The growth medium was removed and cells were washed twice with DMEM. Twenty-five ml of DMEM with 2.5% FBS, 2 mM Gln was added and the cells were then transfected with 30 µg of plasmid /Lipofectamine 2000. After 24 h, the cells were harvested.

Human 293TT cells in each T150 flask were lysed in 1 ml of buffer containing 0.1 M sodium phosphate, 0.15M NaCl, 1% Triton X-100 supplemented with protease inhibitors at pH 7.4 when incubated with V5- or flag-antibody resins or at pH 8.0 for lysates incubated with streptactin beads. After 1 h at 4°C, the debris was removed by centrifugation for 10 min at 10,600 × g. An aliquot was saved for analysis of the postnuclear supernatant/cell extract. The remainder was rotated overnight with 20–30 µl of packed beads of streptactin (IBA), flag- or V5-antibody conjugated agarose (Bethyl, Montgomery, Tx). In the morning the beads were spun down by centrifugation at 3000 × g for 3 min. and then washed 5× with lysis buffer supplemented with phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride and N-ethylmaleimide. Each wash was followed by a 2-min incubation on ice and then a 4 sec spin at 6000 × g. NuPage 2X LDS protein sample buffer (Invitrogen) was added and the bound proteins were eluted by heating at 95°C for 4 min followed by 5 min centrifugation at 16,000 × g. The reducting agent, 0.1 M dithiothreitol final concentration, was added prior to SDS-PAGE.

Western blotting

Whole-cell lysates or purified proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE on 4 to 12% Novex NuPAGE acrylamide gels with 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid–SDS running buffer and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes using miniiBlot gel transfer stacks (Invitrogen). The membrane was blocked with 5% nonfat milk in PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 and then incubated with a primary antibody overnight at 4°C and washed with PBS containing Tween 20 followed by PBS without detergent. For chemiluminescence detection, the appropriate secondary antibody conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (Pierce, Rockford, IL) was added and the blot was washed and developed using Dura or Femto chemiluminescent substrate (Pierce). For fluorescent detection, donkey anti-mouse IRDye 680/800 and donkey anti-rabbit IRDye 680/800 were used and developed using a LI-COR Odyssey infrared imager (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE). To reprobe the blots with additional antibodies, the nitrocellulose membrane was stripped at 55°C for 20 min using Restore buffer (Pierce) or Newblot Nitro stripping buffer (LI-COR).

Acknowledgments

We thank Catherine Cotter for providing cells and other members of the Laboratory of Viral Diseases for helpful discussions. The research was supported by the Division of Intramural Research, NIAID, NIH.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bisht H, Weisberg AS, Moss B. Vaccinia Virus L1 protein is required for cell entry and membrane fusion. J. Virol. 2008;82:8687–8694. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00852-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown E, Senkevich TG, Moss B. Vaccinia virus F9 virion membrane protein is required for entry but not virus assembly, in contrast to the related l1 protein. J. Virol. 2006;80:9455–9464. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01149-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu WL, Lin CL, Yang MH, Tzou DLM, Chang W. Vaccinia virus 4c (A26L) protein on intracellular mature virus binds to the extracellular cellular matrix laminin. J. Virol. 2007;81:2149–2157. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02302-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung C-S, Hsiao J-C, Chang Y-S, Chang W. A27L protein mediates vaccinia virus interaction with cell surface heparin sulfate. J. Virol. 1998;72:1577–1585. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.2.1577-1585.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung CS, Chen CH, Ho MY, Huang CY, Liao CL, Chang W. Vaccinia virus proteome: Identification of proteins in vaccinia virus intracellular mature virion particles. J. Virol. 2006;80:2127–2140. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.5.2127-2140.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earl PL, Cooper N, Wyatt LS, Moss B, Carroll MW. Preparation of cell cultures and vaccinia virus stocks. In: Ausubel FM, Brent R, Kingston RE, Moore DD, Seidman JG, Smith JA, Struhl K, editors. Current Protocols in Molecular Biology. Vol. 2. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 1998a. pp. 16.16.1–16.16.3. [Google Scholar]

- Earl PL, Moss B. Characterization of recombinant vaccinia viruses and their products. In: Ausubel FM, Brent R, Kingston RE, Moore DD, Seidman JG, Smit JA, Struhl K, editors. Current Protocols in Molecular Biology. Vol. 2. New York: Greene Publishing Associates & Wiley Interscience; 1998. pp. 16.18.1–16.18.11. [Google Scholar]

- Earl PL, Moss B, Wyatt LS, Carroll MW. Generation of recombinant vaccinia viruses. In: Ausubel FM, Brent R, Kingston RE, Moore DD, Seidman JG, Smith JA, Struhl K, editors. Current Protocols in Molecular Biology. Vol. 2. New York: Greene Publishing Associates & Wiley Interscience; 1998b. pp. 16.17.1–16.17.19. [Google Scholar]

- Foo CH, Lou H, Whitbeck JC, Ponce-de-Leon M, Atanasiu D, Eisenberg RJ, Cohen GH. Vaccinia virus L1 binds to cell surfaces and blocks virus entry independently of glycosaminoglycans. Virology. 2009;385:368–382. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao JC, Chung CS, Chang W. Vaccinia virus envelope D8L protein binds to cell surface chondroitin sulfate and mediates the adsorption of intracellular mature virions to cells. J. Virol. 1999;73:8750–8761. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.10.8750-8761.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izmailyan RA, Huang CY, Mohammad S, Isaacs SN, Chang W. The envelope G3L protein is essential for entry of vaccinia virus into host cells. J. Virol. 2006;80:8402–8410. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00624-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin CL, Chung CS, Heine HG, Chang W. Vaccinia virus envelope H3L protein binds to cell surface heparan sulfate and is important for intracellular mature virion morphogenesis and virus infection in vitro and in vivo. J. Virol. 2000;74:3353–3365. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.7.3353-3365.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss B. Poxvirus entry and membrane fusion. Virology. 2006;344:48–54. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.09.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss B. Poxviridae: the viruses and their replication. In: Knipe DM, Howley PM, editors. Fields Virology. Vol. 2. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007. pp. 2905–2946. 2 vols. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson GE, Wagenaar TR, Moss B. A conserved sequence within the H2 subunit of the vaccinia virus entry/fusion complex is Important for interaction with the A28 subunit and infectivity. J. Virol. 2008;82:6244–6250. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00434-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols RJ, Stanitsa E, Unger B, Traktman P. The vaccinia I2L gene encodes a membrane protein with an essential role in virion entry. J. Virol. 2008;82:10247–10261. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01035-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojeda S, Domi A, Moss B. Vaccinia virus G9 protein is an essential component of the poxvirus entry-fusion complex. J. Virol. 2006;80:9822–9830. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00987-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojeda S, Senkevich TG, Moss B. Entry of vaccinia virus and cell-cell fusion require a highly conserved cysteine-rich membrane protein encoded by the A16L gene. J. Virol. 2006;80:51–61. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.1.51-61.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resch W, Hixson KK, Moore RJ, Lipton MS, Moss B. Protein composition of the vaccinia virus mature virion. Virology. 2007;358:233–247. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satheshkumar PS, Moss B. Characterization of a newly Identified 35 amino acid component of the vaccinia virus entry/fusion complex conserved in all chordopoxviruses. J. Virol. 2009;83:12822–12832. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01744-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt TG, Skerra A. The Strep-tag system for one-step purification and high-affinity detection or capturing of proteins. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:1528–1535. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senkevich TG, Moss B. Vaccinia virus H2 protein is an essential component of a complex involved in virus entry and cell-cell fusion. J. Virol. 2005;79:4744–4754. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.8.4744-4754.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senkevich TG, Ojeda S, Townsley A, Nelson GE, Moss B. Poxvirus multiprotein entry-fusion complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:18572–18577. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509239102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senkevich TG, Ward BM, Moss B. Vaccinia virus A28L gene encodes an essential protein component of the virion membrane with intramolecular disulfide bonds formed by the viral cytoplasmic redox pathway. J. Virol. 2004;78:2348–2356. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.5.2348-2356.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Townsley A, Senkevich TG, Moss B. Vaccinia virus A21 virion membrane protein is required for cell entry and fusion. J. Virol. 2005;79:9458–9469. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.15.9458-9469.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagenaar TR, Ojeda S, Moss B. Vaccinia virus A56/K2 fusion regulatory protein interacts with the A16 and G9 subunits of the entry fusion complex. J. Virol. 2008;82:5153–5160. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00162-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoder JD, Chen TS, Gagnier CR, Vemulapalli S, Maier CS, Hruby DE. Pox proteomics: mass spectrometry analysis and identification of Vaccinia virion proteins. Virol. J. 2006;3:10. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-3-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]