Abstract

Synthesis of 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3-3β-bromoacetate (1,25(OH)2D3-3-BE), a potential anti-cancer agent is presented. We also report that mechanism of action of 1,25(OH)2D3-3-BE may involve reduction of its catabolism, as evidenced by the reduced and delayed expression of 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3-24-hydroxylase (CYP24) gene in cellular assays.

Keywords: synthesis of 1,25(OH)2D3-3-BE; anti-cancer agent; mechanism of action of 1,25(OH)2D3-3-BE; 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3-24-hydroxylase (CYP24)

The awareness of the potential beneficial effect of vitamin D in a number of diseases, and general good health has increasingly become a public health issue [1]. In addition, the therapeutic potential of 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (1,25(OH)2D3), the dihydroxylated metabolite of vitamin D3, on established tumors was realized when the potent antiproliferative property of 1,25(OH)2D3 was discovered in the early 1980’s in leukemic cells [2]. Since then the antiproliferative and pro-differentiative effects of 1,25(OH)2D3 has been studied in various cancer cell lines, and as a result, 1,25(OH)2D3 has been investigated as a potential anti-cancer agent [3]. However, clinical trials have demonstrated strong calcemic and calciuric effects at pharmacological doses (of 1,25(OH)2D3) [4]. This limitation provided the search for structural analogs of 1,25(OH)2D3 with potent antiproliferative yet low calcemic properties [4]. This effort, based solely on a Specific Estrogen Receptor Modulator (SERM)-like concept adopted the idea that these analogs would change the conformation of nuclear vitamin D receptor (VDR), the chief modulator of the biological actions of 1,25(OH)2D3 sufficiently from the parent hormone to separate cell-regulatory properties from calcemic property. Numerous such ‘non-calcemic’ analogs (of 1,25(OH)2D3) have been synthesized based on this concept with the hope of achieving a favorable antiproliferative/toxicity index, yet clinical results are largely disappointing [5,6].

On the other hand, recent clinical trials of 1,25(OH)2D3 either alone or in combination with common cancer therapeutic drugs have produced strongly encouraging results, and brought back the realization that 1,25(OH)2D3 is probably the most promising ‘drug’ if its therapeutic dose can be escalated without causing toxicity [7-10]. High doses of 1,25(OH)2D3 are required to counter its non-tumor specific spread, and high catabolic rate. Realizing this unmet potential of 1,25(OH)2D3-therapy, we adopted a hypothesis-based alternate approach to increase the half-life of 1,25(OH)2D3, to thus decrease effective dose with reduced toxicity.

1α,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3-3β-bromoacetate (1,25(OH)2D3-3-BE) was initially developed in our laboratory as an affinity labeling reagent to map the ligand-binding domain (LBD) of VDR [11]. Subsequently, we realized that since 1,25(OH)2D3-3-BE covalently attaches to VDR-LBD [12-15], it might be physically protected from interacting with catabolic enzymes, thereby increasing its half-life. Furthermore, once attached to the VDR-LBD, 1,25(OH)2D3-3-BE becomes a simple 3-acetate derivative of 1,25(OH)2D3, activating gene transcription similar to 1,25(OH)2D3. In other words, 1,25(OH)2D3-3-BE becomes de facto 1,25(OH)2D3 with an increased half-life by this process. We observed that 1,25(OH)2D3-3-BE has a significantly greater antiproliferative effect than 1,25(OH)2D3 in normal human keratinocytes, supporting our hypothesis [16]. Subsequently several publications from our group and others have demonstrated significantly stronger antiproliferative effect of 1,25(OH)2D3-3-BE and its mono-hydroxylated analog, 25-hydroxyvitamin D3-3β-bromoacetate than 1,25(OH)2D3 in various cancer cells [17-22]. We also observed strong anti-tumor effect of 1,25(OH)2D3-3-BE in mouse model of renal cancer [22], and androgen-insensitive prostate cancer (manuscript in preparation).

The above mentioned results suggest strong therapeutic potential of 1,25(OH)2D3-3-BE, and warrant extensive in vitro and in vivo studies, requiring substantial quantity of 1,25(OH)2D3-3-BE. Previously we reported synthesis of 1,25(OH)2D3-3-BE with a starting material that is no longer available [23] mandating an alternative synthetic procedure for this compound, which is delineated in this communication. Furthermore, our hypothesis about increased stability of 1,25(OH)2D3-3-BE by making it less available to catabolic enzymes remains unproven to date. In this communication we report results of cellular studies to support this hypothesis on the catabolism of this analog.

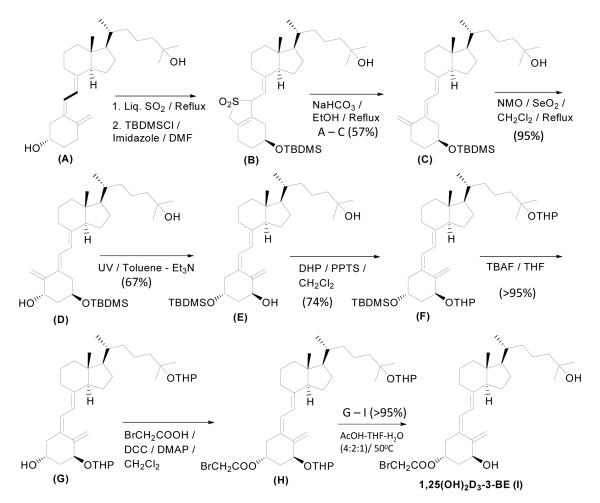

Synthesis of 1,25(OH)2D3-3-BE was initiated by converting 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 (A, Duphar Chemicals, Netherlands) to its trans-variety (B) by the sulfur-dioxide method [24] and converting the crude into the tert.butyldimethylsilylether (TBDMS) derivative (C) (Scheme 1) in good yield.

Scheme 1.

Scheme for the synthesis of 1,25(OH)2D3-3-BE.

Success of our synthetic scheme depended critically on the introduction of the 1-hydroxyl group into (C) by allylic oxidation in a stereospecific manner. In an earlier publication [25] we reported that N-methylmorpholine-N-oxide/SeO2allylic oxidation of 25-hydroxy-5E-[6,19,19′-H3]vitamin D3-3β-tert-butyldimethylsilyl ether to 1α,25-dihydroxy-5E-[6,19,19′-H3]vitamin D3-3β-tert-butyldimethylsilyl ether produced an approximately 6:1 ratio of 1α-OH:1β-OH stereoisomers. However, in the present case HPLC analysis of the crude reaction mixture showed the product to be homogeneous, indicating the presence of a single stereoisomer (D) in the reaction mixture, which, after purification, was identified to have the 1α-OH (desired) stereochemistry by comparison with the NMR spectrum of a known sample [25]. We speculate that the lack of three deuterium atoms in the triene system adjoining the A ring in C may have changed the conformation of the A-ring substantially to have the oncoming oxygen atom introduced exclusively from one side. We also found that stereochemistry at the 1-position depended on the structure of the 1-silyl ether. For example, when 1-OH was derivatized with a triethylsilyl group, the1α-OH:1β-OH ratio was approximately 4:1 with an overall yield of 45%.

In the next step 1α,25-dihydroxy-5E-vitamin D3-3β-tert-butyldimethylsilyl ether (D) was converted to its 5Z counterpart (E) by photolysis. Attempts to protect the 1-hydroxyl group in E as tetrahydropyranyl (THP) ether resulted in the derivatization of the 25-hydroxy group as well, and produced 1α,25-di-tetrahydropyranyloxy, 3β-tert. butyldimethysilyl-5Z-vitamin D3 (F), which was de-silylated to produce 1α,25-di-tetrahydropyranyloxy-5Z-vitamin D3 (G). Finally, G was DCC-coupled to bromoacetic acid, and the resulting product was de-protected to produce 1α,25-dihydroxy-5Z-vitamin D3-3β-bromoacetate (I, 1,25(OH)2D3-3-BE) in nearly quantitative yield.

Signal transduction via 1,25(OH)2D3 is a stepwise process that is initiated by the highly specific binding between 1,25(OH)2D3 and VDR. Ligand binding allosterically promotes formation of a heteromeric complex with RXR, which allows the complex to bind to vitamin D response element(s) in chromatin and recruitment of co-activators, leading to transcription of vitamin D target genes. According to this dogma, VDR-binding by 1,25(OH)2D3 as well as its analogs/derivatives such as 1,25(OH)2D3-3-BE is crucial for all these processes.

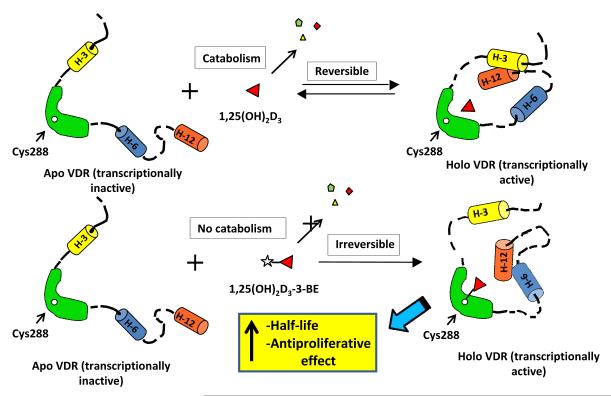

1,25(OH)2D3–3-BE is a VDR affinity alkylating agent. In an earlier study we described that 1,25(OH)2D3-3-BE is capable of specifically labeling native VDR in ROS 17/2.8 bone cells and calf thymus nuclear extract [12], and rapidly titrating recombinant VDR with 1:1 stoichiometry [16]. We also reported that 1,25(OH)2D3-3-BE covalently labels a single cysteine residue (Cys288) in the VDR-LBD (as shown in the cartoon in Figure 1) [14]. Furthermore, we demonstrated that VDR is essential for the growth inhibitory activity of 25-hydroxyvitamin D3-3-BE, a prototype of 1,25(OH)2D3 –3-BE without the 1-hydroxyl group in ALVA-31 prostate cancer cells [19].

Figure 1.

Cartoon depicting interaction between 1,25(OH)2D3, 1,25(OH)2D3-3-BE and VDR. Points to note: (i) reversible and irreversible nature of interaction of 1,25(OH)2D3 and 1,25(OH)2D3-3-BE respectively with VDR, leading to different catabolic outcomes, (ii) covalent attachment of 1,25(OH)2D3-3-BE via Cys288 in VDR-LBD, (iii) differential conformational changes of VDR-LBD induced by 1,25(OH)2D3 and 1,25(OH)2D3-3-BE.

The other mechanistic aspect of our hypothesis delineates that 1,25(OH)2D3-3-BE, after interacting with VDR, is protected from catabolism, thus increasing its half-life, and enhancing its anti-growth property as evidenced in several studies [17-22]. 1α,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3-24-hydroxylase (CYP24) is a cytochrome P450 enzyme that introduces a hydroxyl group at the 24-position in the side chain of 1,25(OH)2D3 that initiates the multi-step catabolic degradation [26]. Interaction between VDR and 1,25(OH)2D3 is an equilibrium process so that the steady state would always contain ‘free’ 1,25(OH)2D3 (not bound to VDR) which will be rapidly catabolized by CYP24 (Figure 1).

In contrast, covalent attachment of 1,25(OH)2D3-3-BE inside the ligand-binding pocket of VDR [14] would eliminate/reduce ‘free’ 1,25(OH)2D3 in the steady state, thereby potentially requiring reduced and delayed expression of CYP24 (Figure 1).

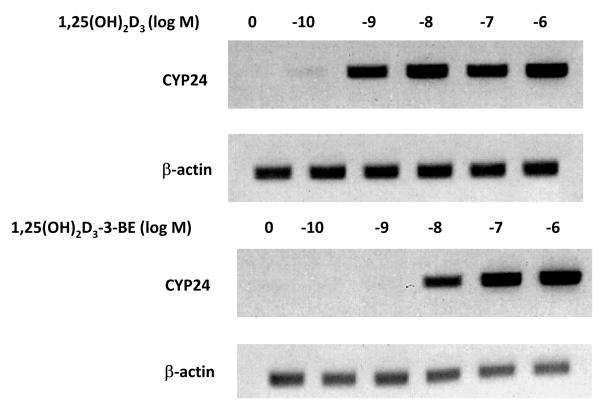

We chose A498 kidney cancer cells to test our hypothesis. In the dose-response experiment A498 cells were treated with 10−10-6M of 1,25(OH)2D3 or 1,25(OH)2D3-3-BE or ethanol vehicle (control). As shown in Figure 2, treatment of A498 cells with 10−10-6M of 1,25(OH)2D3 strongly induced CYP24 mRNA expression. 1,25(OH)2D3-3-BE treatment also led to induction of CYP24 mRNA, but at a significantly higher concentration (approximately 10-fold) to achieve induction comparable to 1,25(OH)2D3, suggesting 1,25(OH)2D3-3-BE is less efficacious in inducing CYP24 than 1,25(OH)2D3, as predicted by our hypothesis.

Figure 2.

Comparison of the dose dependent increase of CYP24 mRNA by 1,25(OH)2D3 and 1,25(OH)2D3-3-BE. A498 cells were treated with ethanol control or 10−10-6 M of 1,25(OH)2D3 and 1,25(OH)2D3-3-BE for 24 hours, total RNA was prepared and CYP24 mRNA levels assessed by RT-PCR. β-Actin mRNA levels were determined for each sample as control. The results are representative of two independent experiments.

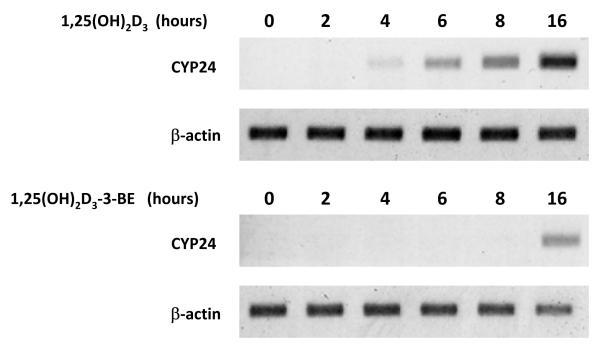

In the kinetic experiment cells were treated with 10−8M of either 1,25(OH)2D3 or 1,25(OH)2D3-3-BE and CYP24 message was detected at various time-points. As shown in Figure 3, induction of CYP24 mRNA was detectable by 4 hr in 1,25(OH)2D3-treated cells and continued to increase over 16 hr. In contrast, 1,25(OH)2D3-3-BE showed a much delayed kinetics of induction of CYP24 mRNA, with CYP24 mRNA first being detectable at 16 hr.

Figure 3.

Kinetics of CYP24 message induction by 1,25(OH)2D3 and 1,25(OH)2D3-3-BE. A 498 cells were treated with 10−8M of 1,25(OH)2D3 and 1,25(OH)2D3-3-BE or ethanol control for 16 hours, total RNA was prepared at specified times and CYP24 mRNA levels assessed by RT-PCR. β-Actin mRNA levels were determined for each sample as control. The results are representative of two independent experiments.

Taken together, results of Figures 2 and 3 suggest that 1,25(OH)2D3-3-BE is less effective in inducing CYP24 gene expression than an equivalent amount of 1,25(OH)2D3. CYP24 is a catabolic enzyme that initiates the degradation of 1,25(OH)2D3. Therefore, reduced and delayed expression of CYP24 gene implies decreased catabolism of 1,25(OH)2D3-3-BE, as predicted by our hypothesis.

We reported earlier that 1,25(OH)2D3-3-BE changes the conformation of VDR differently from 1,25(OH)2D3 as reflected in the enhanced stabilization of VDR-hOCVDRE (human osteocalcin vitamin D response element) complex in COS-1 cells and promotion of a longer stimulation of CYP24 mRNA expression in keratinocytes compared with 1,25(OH)2D3 [16]. Furthermore, recently we reported that compounds similar to 1,25(OH)2D3-3-BE with alkylating bromoacetate group at 1 and 11 positions of 1,25(OH)2D3 specifically labeled VDR-LBD, yet their antiproliferative activity in keratinocytes was similar to that of 1,25(OH)2D3 [27]. Therefore, considering all the information we ascribe enhanced antiproliferative activity of 1,25(OH)2D3-3-BE to a combination of its increased half-life (by covalent labeling of VDR-LBD) and a unique change in VDR-conformation upon binding (Figure 1).

Several non-genomic pathways for the action of 1,25(OH)2D3 and its analogs have also been reported [28]. We have observed that PI3K/Akt non-genomic pathway is involved in the activity of 1,25(OH)2D3-3-BE in kidney cancer cells [22]. Therefore, mechanism of action of 1,25(OH)2D3-3-BE may involve a combination of genomic and non-genomic pathways.

In conclusion, we report an efficient synthesis of 1,25(OH)2D3-3-BE, a potential therapeutic agent for cancer. In addition, we provide data from cellular studies to support our hypothesis about its intrinsic mechanism of action.

Synthesis

(i) A mixture of (C) (760 mg) and SeO2 (192 mg) in 15 ml of anhydrous CH2Cl2 was refluxed under argon for 30 min followed by cooling to room temperature and addition of a solution of N-methylmorpholine-N-oxide (850 mg) in 15 ml of anhydrous CH2Cl2. The mixture was refluxed for an additional 60 min. After usual workup and purification trans-1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3-3β-TBDMS ether (D) was obtained in 95% yield.

(ii) A toluene (10 ml) solution of D (80 mg), anthracene (10 mg), Et3N (40 μl) in a quartz test tube was irradiated from a Hanovia medium pressure mercury arc lamp for 75 min. After preparative TLC purification 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3-3-TBDMS ether (E) was obtained in 67% yield.

Cellular studies

(i) Induction of 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3-24hydroxylase (CYP24) gene expression by 1,25(OH)2D3 and1,25(OH)2D3-3-BE (dose response): A498 kidney cancer cells (ATCC, Manasas, VA) were treated with 10−10-6M of 1,25(OH)2D3, 1,25(OH)2D3-3-BE or ethanol (vehicle control) for 24 hr. Total RNA was prepared and subjected to reverse transcription using Moloney murine leukemia virus (MMLV) reverse transcriptase and random hexamers under standard conditions. Following cDNA synthesis, PCR was performed using gene specific primers to the vitamin D target gene, CYP24 and β-actin (control). The products were analyzed on 1% agarose gels.

(ii) Induction of CYP24 gene expression by 1,25(OH)2D3-3-BE (kinetics): In this experiment A498 cells were treated with 10−8M of 1,25(OH)2D3-3-BE and 1,25(OH)2D3 and RNA prepared over the course of 16 hr for the analysis of CYP24 mRNA levels by RT-PCR.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Cancer Institute grant CA 127629, Department of Defense Grant PC 051136, National Cancer Institute CA126317 (sub-contract) and Community Technology Fund grant, Boston University to R.R., and American Cancer Society Research Scholar Grant RSG-04-170-01-CNE to J.R.L.

Abbreviations

- 1,25(OH)2D3

1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3

- 1,25(OH)2D3-3-BE

1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3-3β-bromoacetate

- VDR

vitamin D receptor

- VDR-LBD

vitamin D receptor-ligand binding domain

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References cited

- [1].Holick MF. Vitamin D: a D-Lightful health perspective. Nutr. Rev. 2008;66:S182. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2008.00104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Abe E, Miyaura C, Sakagami H, Takeda M, Konno K, Yamazaki T, Yoshiki S, Suda T. Differentiation of mouse myeloid leukemia cells induced by 1 alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.USA. 1981;78:4990. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.8.4990. T. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Deeb KK, Trump DL, Johnson CS. Vitamin D signalling pathways in cancer: potential for anticancer therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2007;7:684. doi: 10.1038/nrc2196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Matsuda S, Jones G. Promise of vitamin D analogues in the treatment of hyperproliferative conditions. Mol. Cancer Thera. 2006;5:797. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-05-0539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Dalhoff K, Dancey J, Astrup L, Skovsgaard T, Hamberg KJ, Lofts FJ, Rosmorduc O, Erlinger S, BachHansen J, Steward WP, Skov T, Burcharth F, Evans TR. A phase II study of the vitamin D analogue Seocalcitol in patients with inoperable hepatocellular carcinoma. Brit. J. cancer. 2003;89:252. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Evans TR, Colston KW, Lofts FJ, Cunningham D, Anthoney DA, Gogas H, de Bono JS, Hamberg KJ, Skov T, Mansi JL. A phase II trial of the vitamin D analogue Seocalcitol (EB1089) in patients with inoperable pancreatic cancer. Br. J. Cancer. 2002;86:680. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Muindi JR, Johnson CS, Trump DL, Christy R, Engler KL, Fakih MG. A phase I and pharmacokinetics study of intravenous calcitriol in combination with oral dexamethasone and gefitinib in patients with advanced solid tumors, Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2009;65:33. doi: 10.1007/s00280-009-1000-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Fakih MG, Trump DL, Muindi JR, Black JD, Bernardi RJ, Creaven PJ, Schwartz J, Brattain MG, Hutson A, French R, Johnson CS. A phase I pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic study of intravenous calcitriol in combination with oral gefitinib in patients with advanced solid tumors. Clin. Cancer Res. 2007;13:1216. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Beer TM, Javle MM, Ryan CW, Garzotto M, Lam GN, Wong A, Henner WD, Johnson CS, Trump DL. Phase I study of weekly DN-101, a new formulation of calcitriol, in patients with cancer, Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2007;59:581. doi: 10.1007/s00280-006-0299-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Trump DL, Potter DM, Muindi J, Brufsky A, Johnson CS. Phase II trial of high-dose, intermittent calcitriol (1,25 dihydroxyvitamin D3) and dexamethasone in androgen-independent prostate cancer. Cancer. 2006;106:2136. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21890. DL. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Ray R, Ray S, Holick MF. 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3-3-deoxy-3-bromoacetate, an affinity labeling analog of 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. Bioorg. Chem. 1994;22:276. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Ray R, Swamy N, MacDonald PN, Ray S, Haussler MR, Holick MF. Affinity labeling of 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:2012. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.4.2012. MF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Swamy N, Kounine M, Ray R. Identification of the subdomain in the nuclear receptor for the hormonal form of vitamin D3, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3, vitamin D receptor, that is covalently modified by an affinity labeling reagent. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1997;348:91. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1997.0389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Swamy N, Xu W, Paz N, Hsieh J-C, Haussler MR, Maalouf GJ, Mohr SC, Ray R. Molecular modeling, affinity labeling and site-directed mutagenesis define the key points of interaction between the ligand-binding domain of the vitamin D nuclear receptor and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. Biochem. 2000;39:12162. doi: 10.1021/bi0002131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Mohr SC, Swamy N, Xu W, Ray R. Why do we need a three-dimensional architecture of the ligand-binding domain of the nuclear 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 receptor? Steroids. 2001;66:189. doi: 10.1016/s0039-128x(00)00134-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Chen ML, Ray S, Swamy N, Holick MF, Ray R. Anti-proliferation of human keratinocytes with 1α, 25-dihydroxyvitamin D3-3-bromoacetate, an affinity labeling analog of 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3: mechanistic studies. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1999;370:34. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1999.1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Swamy N, Persons KS, Chen TC, Ray R. 1α,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3-3β-(2)-bromoacetate, an affinity labeling derivative of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 displays strong antiproliferative and cytotoxic behavior in prostate cancer cells. J. Cell. Biochem. 2003;89:909. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10585. R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Swamy N, Chen TC, Peleg S, Dhawan P, Christakos S, Stewart LV, Weigel NL, Mehta RG, Holick MF, Ray R. Inhibition of proliferation and induction of apoptosis by 25-hydroxyvitamin D3-3-bromoacetate in prostate cancer cells. Clin.Cancer Res. 2004;10:8018. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Lambert JL, Young CD, Persons KS, Ray R. Mechanistic and pharmacodynamic studies of a 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 derivative in prostate cancer cells. Biochem. Biophys.Res. Comm. 2007;361:189. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Lange TS, Singh RK, Kim KK, Zou Y, Kalkunte SS, Sholler GL, Swamy N, Brard L. Anti-proliferative and pro-apoptotic properties of 3-bromoacetoxy calcidiol in high risk neuroblastoma. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2007;70:302. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2007.00567.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Persons KS, Eddy VJ, Chadid S, Deoliveira R, Saha AK, Ray R. Anti-growth effect of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3-3-bromoacetate alone or in combination with 5-amino-imidazole-4-carboxamide-1-beta-4-ribofuranoside in pancreatic cancer cells. Anticancer Res. 2010;30:1875. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Lambert JR, Eddy VJ, Young CD, Persons KS, Sarkar S, Kelly JA, Genova E, Lucia MS, Faller DV, Ray R. A vitamin D receptor-alkylating derivative of 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 inhibits growth of human kidney cancer cells and suppresses tumor growth. Cancer Prev. Res. (Phila) 2010;3:1596. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-10-0122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Ray R, Holick SA, Holick MF. Synthesis of a photoaffinity-labelled analog of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Comm. 1985;11:702. [Google Scholar]

- [24].Yamada S, Suzuki t., Takayama H, Miyamoto K, Matsunaga I, Nawata Y. Stereoselective synthesis of (5E)- and (5Z)-vitamin D3-alkanoic acids via vitamin D3-sulfur sulfur dioxide adducts. J. Org. Chem. 1983;48:3483. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Ray R, Vicchio D, Yergey A, Holick MF. Synthesis of 25-hydroxy-[6,19,19′-2H3]vitamin D and 1α,25-dihydroxy-[6,19,19′-2H3]vitamin D3. Steroids. 1992;57:142. doi: 10.1016/0039-128x(92)90072-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Omdahl JL, Swamy N, Serda R, Annalora A, Berne M, Ray R. Affinity labeling of rat cytochrome P450C24 (CYP24) and identification of Ser57 as an active site residue. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2004;89-90:159. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2004.03.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Kaya T, Swamy N, Persons KS, Ray S, Ray R. Covalent labeling of nuclear vitamin D receptor with affinity labeling reagents containing a cross-linking probe at three different positions of the parent ligand: structural and biochemical implications. Bioorg.Chem. 2009;37:57. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Bouillon R, Carmeliet G, Verlinden L, van Etten E, Verstuyf A, Luderer HF, Lieben L, Mathieu C, Demay M. Vitamin D and human health: lessons from vitamin D receptor null mice. Endocr. Rev. 2008;6:726. doi: 10.1210/er.2008-0004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]