Abstract

Dyssynergic defecation is common and affects up to one half of patients with chronic constipation. This acquired behavioral problem is due to the inability to coordinate the abdominal and pelvic floor muscles to evacuate stools. Today, it is possible to diagnose this problem and treat this effectively with biofeedback therapy, history, prospective stool diaries, and anorectal physiological tests. Several randomized controlled trails have demonstrated that biofeedback therapy using neuromuscular training and visual and verbal feedback is not only efficacious but superior to other modalities such as laxative or sham training. Also the symptom improvement is due a change in the underlying pathophysiology. Development of user friendly approaches to biofeedback therapy and use of home biofeedback programs will significantly enhance the adoption of this treatment by gastroenterologists and colorectal surgeons in the future. Improved reimbursement for this proven and relatively inexpensive treatment will carry a significant impact on the problem.

Keywords: Biofeedback therapy, dyssynergic defecation, constipation, treatment

INTRODUCTION

Neuromuscular dysfunction of the defecation unit can lead to disordered or difficult defecation. Among structural and functional causes, the most common entity that causes disordered defecation is dyssynergic defecation. This condition affects about 40% of patients with chronic constipation (1). This is usually an acquired behavioral disorder where the act of stooling is uncoordinated or dyssynergic and comprises of paradoxical anal contraction, inadequate push effort or incomplete anal relaxation with or without altered rectal sensation Clearly, in many patients, there is an overlap, because colonic transit is delayed in two thirds of patients with difficult defecation (1,2).

TREATMENT

The treatment of a patient with dyssynergic defecation consists of: Standard treatment for constipation Specific treatment i.e. neuromuscular training or biofeedback therapy Other measures include botulinum toxin injection, myectomy or ileostomy (1). This chapter will focus on the role of biofeedback therapy.

Standard Treatment

This should consist of a detailed assessment and correction of coexisting issues such as avoiding constipating medications, increasing fiber and fluid intake and exercise activity. In a recent study, dietary instructions had little impact on fiber or nutrient intake in patients with dyssynergia, but about a third of patients were consuming a low fiber diet, and in this group their fiber intake increased (3). In addition, patients should receive instructions regarding timed toilet training and laxatives. Timed toilet training consists of educating the patient to attempt a bowel movement at least twice a day, usually 30 minutes after meals and to strain for no more than 5 minutes. During attempted defecation, they must be instructed to push at a level of 5 to 7, assuming level 10 as their maximum effort of straining (1). They should be encouraged to capitalize on intrinsic physiologic mechanisms that stimulate the colon, such as after waking and after a meal (1). It is important to emphasize that stool impaction should be prevented at all costs. Patients should be advised to refrain from manual maneuvers such as digital disimpaction of stools. Enemas should be generally discouraged although during the initial stages of training or if biofeedback therapy is pending this may be permitted along with use of glycerin or bisacodyl suppositories.

Fiber Supplements

Organic polymers such as bran or psyllium have the ability to hold extra water and often resist digestion and absorption in the upper gut. However, there is no evidence that constipated patients in general consume less fiber than nonconstipated patients, and in fact studies show similar levels of fiber intake (3,4). Furthermore, constipated patients with slow transit or pelvic floor dysfunction respond poorly to dietary supplementation with 30 grams of fiber per day, whereas those without an underlying motility disorder improved (5). A fiber intake of 20 to 30 grams per day is optimal. Recently, both the ACG task force (6) and a systematic review (7) concluded that psyllium, a natural fiber supplement increases stool frequency and gave this compound a grade B recommendation, but there was insufficient data to make a recommendation for the synthetic polysaccharide methylcellulose, or calcium polycarbophil or bran in patients with constipation.

Pharmacologic Approaches

Several types of laxatives are available that include stool softners, stimulant laxatives, osmotic compounds such as polyethylene glycol, magnesium compounds and lactulose and a chloride channel activator such as lubiprostone (1,6,7). These serve as useful adjuncts particularly in the initial management of patients when regularizing their bowel habit and establishing a good bowel regimen.

Specific Treatment

Biofeedback Therapy

The goal of neuromuscular training using biofeedback techniques is to restore a normal pattern of defecation. Neuromuscular training or biofeedback therapy is an instrument-based learning process that is based on “operant conditioning” techniques. The governing principal is that any behavior-be it a complex maneuver such as eating or a simple task such as muscle contraction-when reinforced its likelihood of being repeated and perfected increases several fold. In patients with dyssynergic defecation, the goal of neuromuscular training is two-fold (1,8,9).

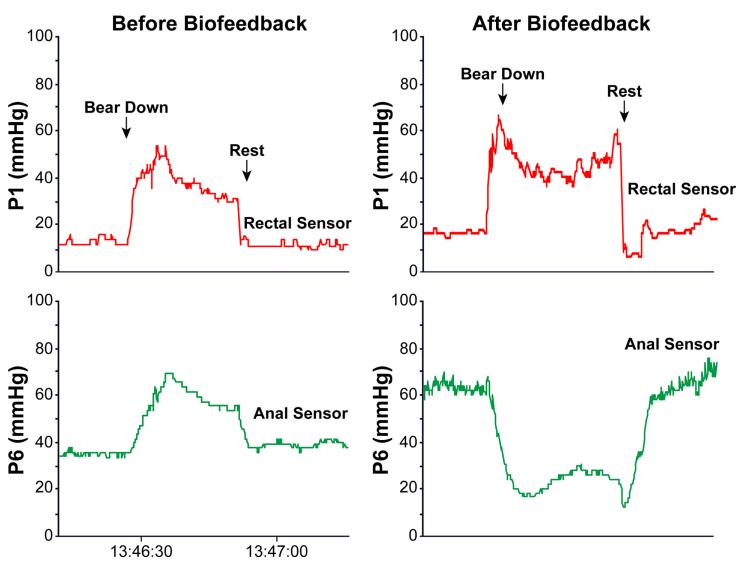

To correct the dyssynergia or incoordination of the abdominal, rectal, puborectalis and anal sphincter muscles in order to achieve a normal and complete evacuation (Fig. 1).

To enhance rectal sensory perception in patients with impaired rectal sensation.

Fig. 1.

The rectal and anal pressure changes, and manometric patterns in a patient with constipation and dyssynergic defecation, before and after biofeedback .

(i) Improve or Correct Dyssynergia

This training consists of improving the abdominal push effort (diaphragmatic muscle training) together with manometric guided pelvic floor relaxation followed by simulated defecation training: An outline of the protocol used at Iowa for biofeedback training is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Biofeedback Therapy for Constipation - Suggested Protocol

|

Phase III: Reinforcement

|

Rectoanal coordination

The purpose of this training is to produce a coordinated defecatory movement that consists of an adequate abdominal push effort as reflected by a rise in intra-rectal pressure on the manometric tracing that is synchronized with relaxation of the pelvic floor and anal canal as depicted by a decrease in anal sphincter pressure (Fig. 1). To facilitate this training, ideally the subject should be seated on a commode with the manometry probe in situ. After correcting the patient’s posture (for example, keeping the legs apart as opposed to keeping them together) and the sitting angle at which he/she will attempt the defecation maneuver, i.e. leaning forward, the subject is asked to take a good diaphragmatic breath and to push and bear down as if to defecate (1,8,9). The subject is encouraged to watch the monitor while performing this maneuver. The subject’s posture and breathing techniques are continuously monitored and corrected. The visual display of the pressure changes in the rectum and anal canal on the monitor provides instant feedback to the subject regarding their performance and helps them to understand and learn quickly [Fig. 1]. At least 10-15 maneuvers are performed.

Next, the balloon in the rectum is distended with 60 cc of air to provide the subject with a sensation of rectal fullness or desire to defecate. As soon as the subject experiences this desire, he/she is then encouraged to push and attempt defecation while observing the pressure changes in the rectum and anal canal on the display monitor. Once again the breathing and postural techniques are corrected. The maneuvers are repeated approximately 5 to 10 times. During the attempted defecation, the patient is instructed to titrate the degree of abdominal push and the anal relaxation effort, and in particular not to push excessively, as this is often counter-productive and leads to voluntary withholding. After each attempt, the balloon is deflated and re-inflated prior to the next attempt. After completion of this maneuver, the balloon is fully deflated and the probe is removed. If using an EMG device, the goal is to teach the subject to either reduce the amplitude of electrical wave forms on the monitor or to decrease the intensity of sound signals (10).

Simulated Defecation Training

The goal of this training is to teach the subject to expel an artificial stool in the laboratory using the correct technique. This maneuver is performed by placing a 50 ml water-filled balloon in the rectum or by using an artificial stool such as Fecom (8,11). After placement of balloon in the left lateral position, the subject is asked to sit on a commode and to attempt defecation. While the subject attempts to pass the balloon, assistance is provided, and the subject is taught how to relax the pelvic floor muscles and to adopt a correct posture and use appropriate breathing techniques. If the subject is unable to expel the balloon, gentle traction is applied to the balloon to supplement the patient’s efforts. Gradually, the subject learns how to coordinate the defecation maneuver and to expel the balloon.

(ii)Sensory Training

The goal of this training is to improve the thresholds for rectal sensory perception and to promote better awareness for stooling (8,11). This is performed by intermittent inflation of the balloon in the rectum. The primary objective is to teach the subject to perceive a particular volume of balloon distention but with the same intensity as they had previously experienced with a larger volume of balloon distention. The first step here is to progressively inflate the balloon until the subject experiences an urge to defecate. This threshold volume is noted. After deflation, the balloon is re-inflated to the same volume and the maneuver is repeated two or three times to educate the subject and to trigger appropriate rectal sensations. Thereafter, with each subsequent inflation, the balloon volume is decreased in a stepwise manner by about 10%. During each distention, the subject is encouraged to observe the monitor and to note the pressure changes in the rectum and simultaneously pay close attention to the sensation they are experiencing in the rectum. They are encouraged to use the visual cues for volumes that are either not readily perceived or only faintly perceived. If the patient fails to perceive a particular volume or reports a significant change in the intensity of perception, the balloon inflation is repeated after a 5 second warning either by using the same volume or by using the previously perceived (higher) volume. Thus, by repeated inflations and deflations and through a process of trial and error, by the end of each session, newer thresholds for rectal perception are established (1,2).

Duration and Frequency of Training

The number of neuromuscular training sessions and the length of each training session should be customized for each patient depending on their individual needs. Typically, each training session takes one hour. Patients are usually asked to visit the motility laboratory once in two weeks. On average, 4 to 6 training sessions are required (8,11). At the outset, it is difficult to predict how many sessions a particular subject will need. After completion of neuromuscular training, periodic reinforcements at six weeks, three months, six months and twelve months may provide additional benefit, and also improve the long term outcome of these patients (8,12), but its role has not been examined.

Devices and Techniques for Biofeedback

Because neuromuscular training is an instrument-based learning technique, several devices and methods are available, and newer techniques continue to evolve. These include manometric-based biofeedback treatment with a solid-state manometry system, EMG biofeedback, balloon defecation training and home training devices (1). The solid-state manometry probe with microtransducers and a balloon is ideally suited for biofeedback therapy. Here, the transducers that are located in the rectum and anal canal provide a visual display of pressure activity throughout the anorectum. This display provides visual feedback to the subject. If required, surface EMG electrodes can be incorporated on the probe to provide both visual and auditory feedback. Sensory training can also be performed with the same probe. Thus, this system can serve as a comprehensive device for neuromuscular training.

Alternatively, an EMG biofeedback system that consists of a surface EMG electrode that is mounted on a probe or affixed to the surface of the external anal sphincter muscle can be used (10,13). These electrodes pick up EMG signals from the surface of the anal sphincter muscle and these are in turn displayed on the monitor. This provides instant visual feedback. The pitch of the auditory signals can be used to provide instant feedback regarding the changes in electrical activity of the anal sphincter. Such feedback responses can augment the learning process by helping the patient to titrate the defecation effort.

Home training devices largely use an EMG home trainer or silicon probe device attached to a hand-held monitor with an illuminated liquid crystal display (LCD). The pressure or electrical activity of the patient’s sphincter responses can be displayed on a simple gauge or on a strip chart recorder or on a color LCD display and these are used to provide visual feedback for the subject.

Efficacy of Biofeedback Therapy

The symptomatic improvement rate has varied between 44% up to 100% in several uncontrolled clinical trials (14). However, when interpreting the outcome of these studies, one should exercise caution because the end point for a successful treatment has been poorly defined, the duration of follow up and the selection of patients has been quite variable. However, in the last few years, several randomized controlled trials of adults with dyssynergic defecation have been reported and are summarized in Table 2. There are significant methodological differences between the studies and in the recruitment criteria as well as in the end points and outcomes. However, all of these studies have concluded that biofeedback therapy is superior to controlled treatment approaches such as diet, exercise and laxatives (11) or use of polyethylene glycol (10), diazepam/placebo (13), balloon defecation therapy (17) or sham feedback therapy (11).

Table 2.

Summary of the randomized controlled trials of biofeedback therapy for Dyssynergic Defecation

| Chiaironi et al (18) | Rao et al (11) | Chiaironi et al (10) | Heymen et al (13) | Rao et al 912) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trial Design | Biofeedback vs PEG 14.6 gms |

Biofeedback vs. standard vs. sham biofeedback |

Biofeedback for slow transit vs Dyssynergia |

Biofeedback vs Diazepam 5 mg vs placebo |

Biofeedback vs Standard therapy |

| Subjects and Randomization |

104 women 54 biofeedback 55 polyethylene glycol |

77 (69 women) 1:1:1 distribution |

52 (49 women) 34 dyssynergia 12 slow transit 6 mixed |

84 (71 women) 30 biofeedback 30 diazepam 24 placebo |

52; Short term therapy 26= long term study 12= biofeedback 13= standard therapy |

| Duration & Number of biofeedback sessions |

3 months & 1 year, 5 weekly, 30 minute training sessions performed by physician investigator |

3 months, Biweekly, one hour, maximum of six sessions over three months, performed by biofeedback nurse therapist |

5 weekly 30 minute training sessions, performed by physician investigator |

6 bi-weekly, one hour sessions | One year; 6 active therapy sessions and 3 reinforcement sessions at 3 month intervals |

| Primary outcomes | Global Improvement of symptoms Worse=0 No improvement=1 Mild=2 Fair=3 Major improvement=4 |

|

Symptom improvement None=1 Mild=2 Fair=3 Major=4 |

Global Symptom relief | Number of complete spontaneous bowel movements Secondary Outcome; Presence of dyssynergia Balloon expulsion time Global satisfaction |

| Dyssynergia corrected or symptoms improved |

79.6% reported major improvement at 6 and 12 months 81.5% reported major improvement at 24 months |

Dyssynergia corrected at 3 months in 79% with biofeedback vs 4% sham and 6% in Standard group ; CSBM= Biofeedback group vs Sham or Standard, p<0.05 |

71 % with dyssynergia and 8% with slow transit alone reported fair improvement in symptoms |

70% improved with biofeedback compared to 38% with placebo and 30 % with diazepam |

No of CSBM/week increased significantly in biofeedback 9p<0.001 Dyssynergia pattern normalized 9p<0.0010 Balloon expulsion improved (p<0.001) Colonic transit normalized (p<0.01) |

| Conclusions | Biofeedback was superior to laxatives |

Biofeedback was superior to sham feedback and standard therapy |

Biofeedback benefits dyssynergia and not slow transit constipation |

Biofeedback is superior to placebo and diazepam |

Biofeedback is superior to standard therapy |

Some of these studies are briefly reviewed below and in table 2.

Chiarioni and colleagues (10) randomized 109 patients with dyssynergia to receive either 5 sessions of EMG biofeedback training or 14.6 grams/day of polyethylene glycol, and assessed outcomes at 6 and 12 months. After 6 months control patients were asked to double the dose to 29.2 g/day for months 7-12. Biofeedback-treated patients reported major satisfaction with treatment (80% vs. 22%, p<0.001) and greater reductions in blocked or incomplete bowel movements, straining, abdominal pain, and use of enemas and suppositories. Stool frequency increased in both groups. .

Rao and colleagues (11) compared anal canal pressure biofeedback to two control conditions – sham biofeedback and standard care – in 77 patients. The sham biofeedback consisted of progressive muscle relaxation exercises for the whole body provided by audiotape plus intermittent distentions of a rectal balloon to match the number of balloon distentions provided to biofeedback subjects. Standard care subjects received diet and life-style advice, laxatives and scheduled evacuations. At 3 months follow-up, the biofeedback treated patients reported significantly more complete spontaneous bowel movements than the other two groups and more improvement in satisfaction with bowel movements than the sham-treated group. These clinical gains were associated with more improvement in defecation dynamics in biofeedback when compared to sham-treated group.

Heymen and colleagues (13) compared EMG biofeedback to two control conditions – diazepam (a skeletal muscle relaxant) 5 mg or placebo one hour before attempted defecation. Prior to randomization, all 117 patients were provided enhanced standard care that included diet, lifestyle measures, stool softeners and scheduled evacuations during a 4-week run-in and those who reported adequate relief at the end of run-in (n=18, 15%) were excluded. Eighty-four patients were randomized. At 3 months follow-up, biofeedback-treated patients reported significantly more unassisted bowel movements than placebo-treated patients (p=0.005) In the intent to treat analysis, 70% of biofeedback group reported adequate relief compared to 23% of diazepam-treated patients (p < 0.001) and 38% of placebo-treated patients (p = 0.017).

Most recently, a one year long term outcome study of biofeedback has been reported that showed that biofeedback is superior to standard therapy alone in patients with dyssynergic defecation (12).

Biofeedback therapy is a labor intensive and multi-disciplinary approach but has no adverse effects. However, it is only offered in a few centers. In order to treat the vast number of constipated patients in the community, a home based, self-training program is essential. A large statewide study that employed home trainers demonstrated the feasibility of home training, but the efficacy of therapy was not compared and objective parameters of anorectal function were not assessed (15). In another European study, significant improvement was reported in most subjects receiving home therapy (16), but there was no control group. Also, one study reported that biofeedback improves both normal and slow transit constipation (17), but a more recent controlled study showed that biofeedback therapy only benefits patients with dyssynergia and normal transit constipation and is not helpful in patients with only slow transit constipation (18).

The mechanism of action of biofeedback therapy is also not known. Although various parameters of colonic and anorectal function (10-14) improve and one study showed improvement in distal colonic blood flow (19 ), the precise alterations are unclear. Recent studies using bidirectional cortical evoked potentials and transcranial magnetic stimulations suggest significant bi-directional brain-gut dysfunction in patients with dyssynergic defecation (20 ). Whether improvement in bowel function correlates with improvement in brain-gut dysfunction remains to be explored.

Practice Points.

Behavioral therapy for constipation with dyssynergic defecation involves both life style modifications, laxatives, establishing a bowel regime and biofeedback therapy

Randomized controlled trials have demonstrated that biofeedback therapy using neuromuscular coordination and training and visual or audio or verbal feedback techniques is effective in improving bowel symptoms and correcting dyssynergic defecation.

Research Agenda.

The mechanism(s) through which biofeedback changes bowel function are poorly understood.

Newer and user friendly methods of biofeedback training including development of home-based biofeedback therapy should be systematically evaluated

Treatment of Sensory dysfunction along with dyssynergic defecation both rectal hypersensitivity and rectal hyposensitivity may further enhance bowel function

Acknowledgement

Dr Rao is supported in part by grant RO1DK57100-03 National Institute of Health and also acknowledge secretarial assistance of Mrs Sara Allen

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: Dr Rao reports no conflict of interest in the context of this report

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Rao SSC. Dyssynergic Defecation and biofeedback therapy. In Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2008;37:569–86. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2008.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rao SSC, Welcher K, Leistikow J. Obstructive Defecation. A failure of rectoanal coordination. Am J. Gastroenterol. 1998;93:1042–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1998.00326.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stumbo PJ, Hemmingway D, Paulson J, et al. How Useful Is Dietary Management in the Treatment of Chronic Constipation? Supplement to Gastroenterology. 2008;134(4):A-469. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Muller-Lissner SA, Kamm MA, Scarpignato C, et al. Myths and misconceptions about chronic constipation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:232–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.40885.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Voderholzer WA, Schatke W, Muhldorfer BE, et al. Clinical Response to Dietary Fiber Treatment of Chronic Constipation. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:95–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brandt LJ, Prather CM, Quigley EM, et al. Systematic review on the management of chronic constipation in North America. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100(Suppl 1):S5–S21. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.50613_2.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ramkumar D, Rao SSC. Efficacy and Safety of Traditional Medical Therapies for Chronic Constipation: Systematic Review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:936–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.40925.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rao SSC, Welcher K, Pelsang RE. Effects of biofeedback therapy on anorectal function in obstructive defecation. Dig Dis Sci. 1997;42:2197–2205. doi: 10.1023/a:1018846113210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rao SSC. The Technical aspects of biofeedback therapy for defecation disorders. The Gastroenterologist. 1998;6:96–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chiarioni G, Salandini L, Whitehead WE. Biofeedback benefits only patients with outlet dysfunction, not patients with isolated slow transit constipation. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:86–97. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rao SS, Seaton K, Miller M, et al. Randomized controlled trial of biofeedback, sham feedback, and standard therapy for dyssynergic defecation. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:331–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rao SSC, Valestin J, Brown CK, et al. Long term efficacy of biofeedback therapy for dyssynergic defecation: randomized Controlled Trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:890–6. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heymen S, Scarlett Y, Jones K. Randomized, controlled trail shows biofeedback to be superior to alternative treatments for patients with pelvic floor dyssynergia-type constipation. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:428–41. doi: 10.1007/s10350-006-0814-9. et au. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Biofeedback treatment of constipation: a critical review. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46(9):1208–17. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-6717-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Patankar SK, Ferrara A, Levy JR, et al. Biofeedback in colorectal practice: a multicenter, statewide, three-year experience. Dis Colon Rectum. 1997;40:827–31. doi: 10.1007/BF02055441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kawimbe BM, Pappachrysostomou M, Binnie NR, et al. Outlet obstruction constipation (anismus) managed by biofeedback. Gut. 1991;32:1175–79. doi: 10.1136/gut.32.10.1175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koutsomanis D, Lennard-Jones J, Kamm MA. Prospective study of biofeedback treatment for patients with slow and normal transit constipation. Eur J. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1994;6:131–37. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chiarioni G, Whitehead WE, Pezza V, et al. Biofeedback is superior to laxatives for normal transit constipation due to pelvic floor dyssynergia. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:657–64. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Emmanuel AV, Kamm MA. Response to a behavioral treatment, biofeedback, in constipated patients is associated with improved gut transit and autonomic innervation. Gut. 2001;49:214–9. doi: 10.1136/gut.49.2.214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Remes-Troche JM, Paulson J, Yamada T, et al. Anorectal cortical Function is Impaired in Patients with Dyssynergic Defecation. Gastroenterology. 2007;108:A20. [Google Scholar]