Abstract

Aims

To examine the influence of traditional tobacco use on smoking cessation among American Indian adult smokers.

Design, setting and participants

A cross-sectional survey of self-identified American Indians was conducted from 2008 to 2009. A total of 998 American Indian adults (18 years and older) from the Midwest, participated in the study.

Measurements

Traditional tobacco use and method of traditional use were both assessed. Commercial tobacco use (current smoking) was obtained through self-reported information as well as the length of their most recent quit attempt. We also assessed knowledge and awareness of pharmacotherapy for current smokers.

Findings

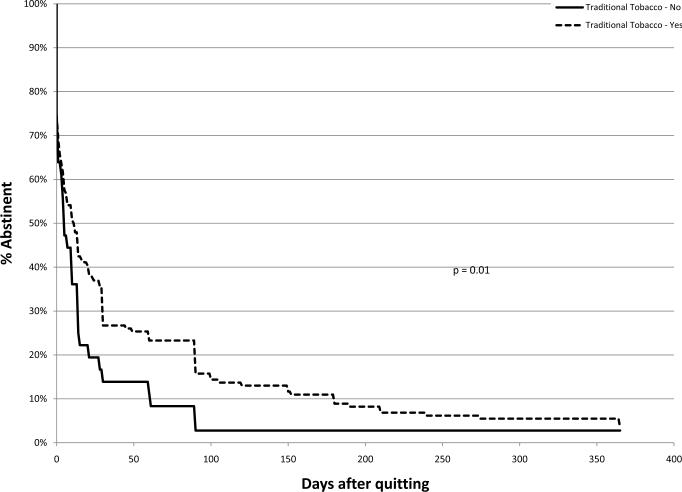

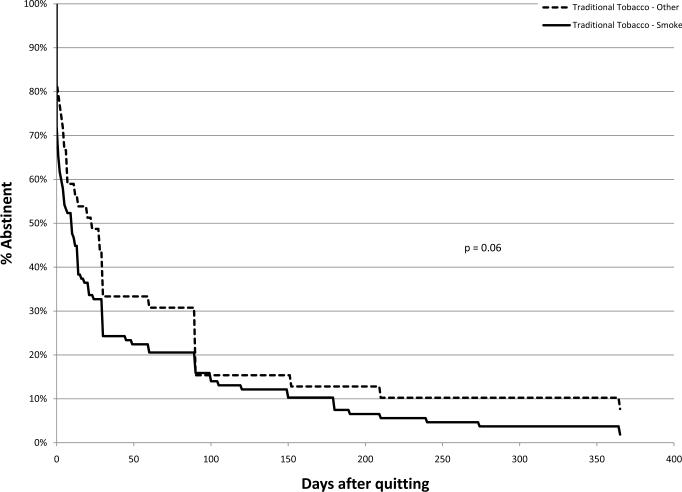

Among participants in our study, 33.3% were current smokers and they reported smoking an average of 10 cigarettes per day. American Indian current smokers who used traditional tobacco reported greater number of days abstinent during their last quit attempt compared to those who do not use traditional tobacco (p=0.01). However, it appears that this protective effect of traditional tobacco use is diminished if the person smokes traditional tobacco. Finally, very few (less than 20% of current smokers) were aware of more recent forms of pharmacotherapy such as Chantix or Bupropion.

Conclusions

American Indians appear to show low levels of awareness of effective pharmacotherapies to aid smoking cessation but those who use `traditional tobacco' report somewhat longer periods of abstinence from past quit attempts.

Keywords: American Indian smokers, traditional tobacco, relapse curves

INTRODUCTION

American Indians and Alaska Natives (AI/AN) have the highest prevalence of cigarette smoking (recreational) among all racial/ethnic groups in the U.S. Although there is some variability in the rates of smoking among AI/AN populations, national surveys have reported that the adults with the highest smoking rates are the AI/AN population [1–3]. While the smoking rates among the US adult population have declined overall in the past 40 years, this decline has not been consistent across all racial/ethnic groups. Specifically, American Indians and Alaska Natives from different regions of the country and tribal communities have experienced a rise in smoking prevalence over the past several decades.

Available data suggest that the AI/AN adolescents start experimenting with smoking at a very young age and are at a greater risk for smoking initiation than Whites [3, 4]. A recent study reported that among racial/ethnic groups, American Indians had the highest median duration of smoking with 32 years, compared to all other groups[5]. On average, American Indians smoked approximately 4 years longer than White smokers, due in large part to delayed cessation. In addition, this same study found that daily smoking was most prevalent in American Indians (49.7%) compared to all other racial/ethnic groups.

Ceremonial tobacco use also varies greatly among tribes and the traditional tobacco that is used for ceremonial or spiritual use is also diverse. Traditional or ceremonial tobacco use occurs in a variety of forms. Tobacco can be offered as a gift to the Creator or as a gift to honor someone. It can be burned in a pipe, dish, shell, or fire, with the smoke believed to carry prayers to the Creator. Therefore, traditional tobacco can be either smoked or used in a way that does not involve any form of smoking. The frequency of traditional tobacco use also differs across individuals and tribes, with some American Indians using traditional tobacco daily and others on special occasions. A previous study reported that smoking rates are generally higher among tribes who use tobacco ceremonially, in contrast to tribes such as those in the Southwest who do not [2].

While it might be difficult to separate the influence of ceremonial or traditional tobacco use from recreational use [6], the unintended consequences of tobacco use contributes greatly to high health care costs and several years of potential life lost in the AI and AN communities [1, 7, 8]. Yet, there is paucity of data regarding tobacco use and smoking cessation practices in this population.

Clinical practice guidelines for smoking cessation recommend that all smokers be offered pharmacotherapy as an adjunct to quitting [9]. Pharmacotherapy, in the form of nicotine replacement therapy, bupropion, or varenicline has been shown to increase the odds of quitting both in placebo-controlled trials [9–11] and in clinical settings [12–14]. In the US general population, only about 20–30% of smokers who have tried to quit used one or more forms of evidence-based cessation aids [15, 16]. In ambulatory settings, less than 2% of smokers receive pharmacotherapy to support a quit attempt [17, 18]. In a recent study conducted by Burgess et al., “cold turkey” was reported as the most common strategy used in quitting among American Indians [19]. Therefore, lack of knowledge of the available options of pharmacotherapy may be responsible in part, for the low utilization of smoking cessation pharmacotherapy in this population.

To better understand the patterns of smoking cessation among American Indians, we conducted a cross-sectional survey of American Indians in the Midwest. In addition, we wanted to examine the influence of traditional tobacco use on smoking abstinence and relapse.

METHODS

Study Participants

Since there is no comprehensive list of American Indian residents of Kansas or the region, we used multiple methods to recruit participants for this study, including: Pow wows, focus groups, health fairs, new student orientation for American Indian students, and other various American Indian events in the region. All research assistants who recruited the participants were American Indian. We recruited 207 participants from pow wows, 211 participants were from focus groups, 124 participants were from health fairs and physicals, 275 were from career fairs and conferences, and the remaining 181 participants from various other events and referrals from other participants. Given the recruiting methods used for this study, these participants may have resulted in a select nature of the sample with respect to the socio-demographic characteristics. We recruited a total of 998 American Indians in the region from May 2008 to December 2009. The cooperation rate for this study was approximately 76% across all methods of recruitment. Participants were reimbursed with a $10 gift card for their time and participation in the study. Each participant completed a self-administered survey related to health behaviors and knowledge, which took approximately 20 minutes to complete.

Men and women who self-identified as American Indian (only or in part) and were at least 18 years of age were eligible to participate in the study. The survey included questions about general health, participant demographics, traditional tobacco use, commercial tobacco use, knowledge and attitudes related to cancer, use of the internet, source of health information and health care, other health related behaviors. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Kansas Medical Center.

Measures

Smoking status

Participants were asked the following questions to determine their current smoking status: “Have you smoked at least 100 cigarettes in your entire life?” and “Do you now smoke cigarettes…. Everyday, somedays, or not at all.” Current (recreational) smokers are those who answered “Yes” to the first question and “everyday or somedays” to the second question. Non smokers were those respondents who responded “not at all” to the above question. Former and never smokers were grouped due to small sample of former smokers.

Traditional Use of Tobacco

We asked the following questions to ascertain information related to traditional use of tobacco for all participants: (1) Do you use tobacco for traditional purposes, such as ceremonial, spiritual, or prayer, etc.” (2) When using tobacco for traditional purposes, how do you use it? (3) What type of tobacco do you use? (4) Does the tobacco that you use for traditional purposes have nicotine in it? (5) On average, how often do you use tobacco for traditional purposes?

Quitting History

In order to estimate the smoking relapse curve for current smokers, participants were asked the following questions related to their quitting history: “Are you seriously thinking about quitting in the next 30 days?” and “In the last 12 months, how many times have you tried to quit smoking for at least one day?” and “On your last quit attempt, how many days did you quit for?”

Awareness of Pharmacotherapy

American Indian participants were asked the following question to determine their knowledge and awareness of the different forms of aid for smoking cessation: “Which of these drugs to help you quit smoking have you heard of?” (Chantix®, Zyban®, Patch, Nicotine Gum, and Nicotine Lozenges).

Data Analysis

Discrete variables are described using frequency and percentage. Means and standard deviations are used to describe continuous variables. Parametric tests were used for the comparisons between groups: Chi-square test in the case of categorical variables and the t-test in the case of quantitative variables. The relapse curves were generated using the Kaplan-Meier method and the log-rank test was employed to compare the curves for groups of interest. We adjusted for age and gender as covariates in the survival analysis. Statistically significant associations and differences were identified by p values of less than 0.05. All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.2 (Copyright (c) 2002–2008 by SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

RESULTS

Table 1 shows the demographic distribution of all participants. The mean age of the participants was 33.5 years and approximately 58% were females. The majority of the participants grew up in a non-urban area (66%) with 46% from reservations and 20% from rural. Over 65% of the participants reported completing some college education. The overwhelming majority (98%) reported some type of health insurance.

Table 1.

Baseline demographics for the overall sample of American Indians

| Demographic variable | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age (mean +/− SD) | 33.5 (15.5) | |

|

| ||

| Gender | ||

| Male | 419 | 42.2 |

| Female | 574 | 57.8 |

|

| ||

| Where did you grow up? | ||

| (sub) Urban | 310 | 33.2 |

| Rural | 191 | 20.4 |

| Reservation | 434 | 46.4 |

|

| ||

| Education | ||

| < High school | 43 | 4.3 |

| High school graduate | 283 | 28.6 |

| Any college | 518 | 52.4 |

| College graduate | 145 | 14.7 |

|

| ||

| Employment status | ||

| Employed | 385 | 45.7 |

| Unemployed | 105 | 12.5 |

| Student | 352 | 41.8 |

|

| ||

| Health Insurance Status | ||

| No insurance | 16 | 1.6 |

| Indian Health Service | 295 | 29.6 |

| Other insurance | 687 | 68.8 |

Table 2 presents the smoking characteristics for current smokers in our sample. Of the 998 total participants, 33.3% were current smokers who smoked an average of 10 cigarettes per day. Fewer than 40% of the smokers smoked their first cigarette within 30 minutes of waking. Approximately half of the smokers reported living with other smokers in the household. Among the current smokers, the mean number of days for their most recent quit attempt was 67 days. Most smokers (78%) reported using traditional tobacco and of these participants, 75% used traditional tobacco in a form that involved smoking it.

Table 2.

Smoking status and characteristics among current American Indian smokers.

| Demographic variable | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Smoking status | ||

| Smoke everyday | 176 | 17.6 |

| Smoke somedays | 156 | 15.6 |

| Nonsmoker | 666 | 66.7 |

|

| ||

| Current Smokers | ||

|

| ||

| Cigarettes smoked per day (mean +/− SD) | 10.1 cigs | (13.2) SD |

|

| ||

| Longest quit attempt (mean +/− SD) | 67.4 days | (235.9) SD |

|

| ||

| Smokes first cigarette within 30 minutes of waking | ||

| No | 179 | 62.4 |

| Yes | 108 | 37.6 |

|

| ||

| Other smokers in the household | ||

| No | 171 | 51.5 |

| Yes | 161 | 48.5 |

Table 3 shows the different ways in which traditional tobacco was used by gender and smoking status. The results indicate that a higher proportion of current smokers use traditional tobacco (males and females) compared to non-smokers. There was also differences in the frequency of traditional tobacco use, with 48% of male current smokers using traditional tobacco weekly, compared to only 24% of female current smokers.

Table 3.

Use of Traditional Tobacco by commercial smoking status by gender

| Current smokers | Non-smokers | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males (%) | Females (%) | Males (%) | Females (%) | |

| Use tobacco for traditional purposes | 77.6 | 77.9 | 63.0 | 64.8 |

| Traditional tobacco is “smoked” | 80.4 | 70.9 | 60.3 | 50.0 |

| Traditional tobacco is “smudged*” | 27.1 | 22.0 | 15.3 | 17.5 |

| Traditional tobacco is used as “offering or prayer” | 50.7 | 43.6 | 34.6 | 35.6 |

| Traditional tobacco is given as a “gift” | 32.6 | 22.6 | 17.4 | 16.2 |

| Frequency of traditional tobacco use (At least weekly) | 48.1 | 24.0 | 26.0 | 15.7 |

Smudged – can refer to several different uses of tobacco or other sacred plants. The most common uses of the term include burning tobacco and using the ashes to bless something or someone or burning tobacco, allowing the smoke to waft over someone or someplace as part of a purification ritual. It does not refer to inhaling smoke as part of any ritual or ceremony and it is important to note that not all American Indian people use the term nor the practice.

All participants were asked about their knowledge and awareness of all the current forms of pharmacotherapy and nicotine replacement therapy (NRT). Table 4 presents the results by gender and smoking status. Across all forms of NRT and pharmacotherapy, current smokers reported a higher level of awareness compared to non-smokers in both males and females. For the over the counter forms of NRT (patch and gum), the majority (60%– 66%) of American Indian smokers reported that they have heard of these cessation aids and were aware of their availability, compared to approximately 50% of nonsmokers. However, for the most current recommended pharmacotherapy such as Chantix® or Zyban®, the percentage of American Indian smokers who were aware of these new cessation aids was low, approximately 16–25% and less than 15% among nonsmokers. .

Table 4.

Awareness of NRT/Pharmacotherapy

| Males | Females | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NRT/Pharmacotherapy | Current | Non-smoker | p-value | Current | Non-smoker | p-value |

| Chantix | 25.3 | 14.4 | 0.0015 | 16.0 | 10.2 | 0.0851 |

| Zyban | 20.0 | 13.4 | 0.0444 | 18.1 | 11.3 | 0.0544 |

| Nicotine Patch | 66.7 | 48.7 | 0.0001 | 60.4 | 48.7 | 0.0228 |

| Nicotine Gum | 65.6 | 49.5 | 0.0003 | 55.6 | 50.2 | 0.2957 |

| Nicotine Lozenge | 28.0 | 23.7 | 0.2721 | 27.1 | 18.6 | 0.0433 |

Figure 1 shows the survival curves for all current smokers by traditional tobacco use. American Indian current smokers who used traditional tobacco had higher abstinence rates compared to those who do not use traditional tobacco (p=0.01). However, it appears that this protective effect of traditional tobacco use is diminished if the person smokes traditional tobacco, Figure 2.

Figure 1.

Figure 2.

The mean number of days abstinent for those who used traditional tobacco (87 days) was almost 5 times longer than those who did not use traditional tobacco (18 days) (Data not shown). However, among those who used traditional tobacco, those who reported smoking traditional tobacco (55 days) had a much smaller mean number of days abstinent, compared to those who did not smoke traditional tobacco (172 days). The mean number of days abstinent were not considerably different by smoking frequency (71 days: “everyday” vs 63 days: “somedays”) or by smoking level (71 days: light smokers vs 65 days: moderate/heavy smokers).

DISCUSSION

The major finding in this descriptive study of American Indian smokers is that traditional use of tobacco is not a detriment to quitting, and may in fact be correlated with greater cessation. However, this protective effect appears to diminish considerably if the person smokes traditional tobacco. In addition, the relapse curves presented in this study certainly support the use of pharmacotherapy for American Indian smokers as their relapse and abstinence experience is similar to other smokers from other racial/ethnic minority groups. We were very surprised to find that only 20% of the current smokers in our study were aware of the latest form of pharmacotherapy, Chantix® or Zyban®. Even the over-the-counter forms of NRT, such as the patch and gum were only reported by 60% of the smokers, which is lower than expected. Similar studies in other racial/ethnic groups (African Americans, Latinos, and Asians) reported a much higher awareness of these forms of NRT or pharmacotherapy for cessation. Reasons for this lack of awareness are unknown and need to be further examined.

Anecdotal evidence from this and other studies conducted by the authors suggest that traditional tobacco may have a protective effect because individuals feel they disrespect the sacred plant when using it recreationally. This belief is strengthened when an individual attempts to quit smoking because he or she starts to think more about the sacred nature of the plant and the appropriate use of it. Several participants in both focus groups and our smoking cessation studies have mentioned that as they start to think about recreational smoking as damaging to their health, they begin to also think about it as an abuse of a sacred plant. When tobacco is smoked for traditional purposes rather than offered as a gift, smudged, or otherwise used, the nicotine will continue to trigger the same response. It is possible that this is why the protective effect of traditional use disappears with individuals who smoke tobacco traditionally.

This study has several limitations. First, this was a cross-sectional study of American Indians attending health fairs and pow wows in the Midwest and therefore, cohort or longitudinal studies should be conducted to replicate our findings related to traditional tobacco use. Second, all responses, including smoking status were self-reported and were not confirmed by biochemical verification. In addition, we did not collect detailed information on the use of smokeless tobacco. However, given that these surveys were anonymous, there is no reason to believe any bias was introduced and self-reported smoking status have been validated in prior studies on smoking status. A major strength of this study was the collection of information related to traditional tobacco use. Most prior studies of American Indian smokers have not examined the influence of traditional tobacco use on recreational smoking. This is the first study to examine this and to present the smoking abstinence and relapse curves by traditional tobacco use.

Identification of relapse subgroups may have important implications for treatment of smoking relapse, especially, for this underserved population of smokers. Currently, there are too few American Indian cessation clinical trials. There are two trials involving the Alaska Native population, one in youth and the other in pregnant women, both led by the Mayo Clinic. Another current trial is currently being conducted in the Menominee nation by the University of Wisconsin. The fourth clinical trial of American Indian smoking cessation is the ongoing clinical trial involving a culturally-tailored smoking cessation program involving use of pharmacotherapy/nicotine replacement therapy for American Indian smokers to quit smoking at the University of Kansas Medical Center. The results from this current study support a culturally-tailored smoking cessation program that addresses traditional tobacco use for American Indian smokers. All of these studies can potentially contribute to a better understanding of how to improve treatment of commercial tobacco use in the American Indian population.

Significantly more research is needed, both to verify these findings related to the influence of traditional tobacco use and to create more effective, culturally-tailored smoking cessation programs for American Indian smokers.

Acknowledgements

Funding for this study was provided by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (R24MD002773) and the American Lung Association (ALA SB-40588-N).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This paper has been accepted for publication in Addiction and is currently being edited and typeset. Readers should note that this paper has been fully refereed, but has not been through the copyediting and proof correction process. Wiley-Blackwell and the Society for the Study of Addiction cannot be held responsible for errors or consequences arising from the use of information contained in this paper; nor do the views and opinions expressed necessarily reflect those of Wiley-Blackwell or the Society for the Study of Addiction. The article has been allocated a unique Digital Optical Identifier (DOI), which will remain unchanged throughout publication. Please cite this article as a “Postprint”;

REFERENCES

- 1.Denny CH, Holtzman D, Cobb N. Surveillance for health behaviors of American Indians and Alaska Natives. Findings from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 1997–2000. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2003;52(7):1–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nez Henderson P, Jacobsen C, Beals J. Correlates of cigarette smoking among selected Southwest and Northern plains tribal groups: the AI-SUPERPFP Study. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(5):867–72. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.050096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nez Henderson P, et al. Patterns of cigarette smoking initiation in two culturally distinct American Indian tribes. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(11):2020–5. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.155473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eichner JE, et al. Tobacco use among American Indians in Oklahoma: an epidemiologic view. Public Health Rep. 2005;120(2):192–9. doi: 10.1177/003335490512000214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Siahpush M, et al. Racial/ethnic and socioeconomic variations in duration of smoking: results from 2003, 2006 and 2007 Tobacco Use Supplement of the Current Population Survey. J Public Health (Oxf) 2010;32(2):210–8. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdp104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kegler MC, Cleaver VL, Yazzie-Valencia M. An exploration of the influence of family on cigarette smoking among American Indian adolescents. Health Educ. Res. 2000;15(5):547–557. doi: 10.1093/her/15.5.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roubideaux Y. Beyond Red Lake--the persistent crisis in American Indian health care. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(18):1881–3. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp058095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bulterys M. High incidence of sudden infant death syndrome among northern Indians and Alaska natives compared with southwestern Indians: possible role of smoking. J Community Health. 1990;15(3):185–94. doi: 10.1007/BF01350256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fiore M, Bailey W, Cohen S. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: Clinical Practice Guideline. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Public Health Service; Rockville, MD: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fiore MC, Jaen CR. A clinical blueprint to accelerate the elimination of tobacco use. Jama. 2008;299(17):2083–5. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.17.2083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.A clinical practice guideline for treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update. A U.S. Public Health Service report. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35(2):158–76. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rigotti N, Munafo M, Stead L. Interventions for smoking cessation in hospitalised patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(3):CD001837. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001837.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rigotti NA, et al. Bupropion for smokers hospitalized with acute cardiovascular disease. Am J Med. 2006;119(12):1080–7. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ranney L, et al. Systematic review: smoking cessation intervention strategies for adults and adults in special populations. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(11):845–56. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-11-200612050-00142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cokkinides VE, et al. Under-use of smoking-cessation treatments: results from the National Health Interview Survey, 2000. Am J Prev Med. 2005;28(1):119–22. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shiffman S, et al. Use of smoking-cessation treatments in the United States. Am J Prev Med. 2008;34(2):102–11. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ferketich AK, Khan Y, Wewers ME. Are physicians asking about tobacco use and assisting with cessation? Results from the 2001–2004 national ambulatory medical care survey (NAMCS) Prev Med. 2006;43(6):472–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2006.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thorndike AN, Regan S, Rigotti NA. The treatment of smoking by US physicians during ambulatory visits: 1994 2003. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(10):1878–83. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.092577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burgess D, et al. Beliefs and experiences regarding smoking cessation among American Indians. Nicotine Tob Res. 2007;9(Suppl 1):S19–28. doi: 10.1080/14622200601083426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]