Abstract

We report a case of successful endovascular treatment of bilateral carotid artery occlusion with concurrent basilar apex aneurysm. An elderly female patient with subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) onset was admitted to the hospital. Computed tomography (CT) and digital subtraction angiography (DSA) confirmed the presence of bilateral carotid artery occlusion with concurrent basilar apex aneurysm. Brain blood supply was provided by the bilateral vertebral artery through the basilar artery. We treated the aneurysm with the endovascular approach by embolizing the aneurysm with three coils. The patient recovered well after surgery and showed no recanalization of the aneurysm on a one-year follow-up DSA. We also reviewed six similar cases found with a PUBMED database search (1980-2010), including those with bilateral common carotid artery occlusion. In conclusion, by using the endovascular approach, bilateral carotid artery occlusion with concurrent basilar apex aneurysm was efficiently treated.

Keywords: carotid artery occlusion, basilar apex aneurysm, endovascular treatment

1. Introduction

Bilateral carotid artery occlusion with concurrent basilar apex aneurysm is extremely rare 1. When it occurs, the brain blood supply mainly relies on the vertebral artery through the basilar artery. The unnatural reliance on this route is such that the pressure inside the apex of the basilar artery makes it vulnerable to aneurysm 2-4. These need to be treated quickly, as they may cause hemorrhaging and subsequent death 3,5.

Craniotomy is one approach to treat patients with basilar apex aneurysm. However, in the case of a bilateral carotid artery occlusion, the increased blood pressure in the basilar artery leads to higher risks in the surgical clipping of aneurysms 3,6. The alternative approach is the endovascular treatment that has been developed since 1991 7,8. It is performed with the guidance of DSA, for accurate localization during surgery with minimal tissue damage.

Here we report a case of successful treatment of bilateral carotid artery occlusion with concurrent basilar apex aneurysm using the endovascular approach. In addition, we reviewed six similar cases found through a PUBMED database search for the years 1980-2010, including cases with bilateral common carotid artery occlusion. These cases further supported the application of endovascular treatment for bilateral carotid artery occlusion with concurrent basilar apex aneurysm.

2. Case Report

The female patient aged 69 was admitted to the hospital after reporting a sudden headache accompanied by nausea and vomiting for ten days. The patient had a history of hypertension for 4 years and diabetes for 10 years, which were well-controlled with antihypertensive and oral hypoglycemic medication. Upon admission to the hospital, the patient presented with Hunt-Hess grade III and positive Kernig's signs. CT scan showed that the hemorrhage was localized on the pontine cistern and interpeduncular cistern, extending to the right of the ambient cistern into the posterior horn of the right ventricle. The patient was diagnosed with SAH, diabetes and hypertension.

CTA showed an aneurysm at the apex of the basilar artery with a diameter of 3.2 mm. There was no signal at the bilateral internal carotid artery, and the bilateral posterior communicating artery was supplying the anterior circulation. This result led to a diagnosis of bilateral carotid artery occlusion with concurrent basilar apex aneurysm. DSA showed that the bilateral internal carotid artery was occluded from the beginning of the bifurcation, with the external carotid artery system developed and no signs of anastomosis or vascular reconstruction of the branches of the external carotid and intracranial arteries. The brain blood supply mainly relied on the vertebral artery through the bilateral posterior communicating arteries. The angiograph of the vertebral artery showed no delay in the blood flow of anterior circulation. The saccular aneurysm with a diameter of 3.2 mm was observed at the apex of the basilar artery.

Under general anesthesia, three coils [3 mm × 5 cm Morpheus 3D CSR (Ev3), 2 mm × 1 cm Morpheus 3D CSR (Ev3), and 2 mm × 1 cm Helical (MicroVention)] were used to embolize the aneurysm, and the patient recovered well. After one year, DSA showed no aneurysm recanalization.

3. Literature review

We reviewed 6 similar cases of bilateral carotid artery occlusion with concurrent basilar apex aneurysm found with a PUBMED search for the years 1980 to 2010 3,5,9-12. These studies included cases of bilateral common carotid artery occlusion. The clinical data is summarized in Table 1. The following is a summary of the studies.

Table 1.

Clinical data for all cases in this study.

| Case | Study | Year | Age/ gender | Cause | Position of Occlusion | Symptom | Other aeurysms | Collateral circulation | Treatment | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Kumagai et al. 9 | 1981 | 41/F | aortitis | Begnning of the CCA | SAH | PCA | VA→ECA→ICA | Clipping (BA aneurysm)+ Clipping (others) | Good Recovery |

| 2 | Matsuzawa et al. 5 | 1982 | 54/F | aortitis | Begnning of the CCA | SAH | No | Subclavian artery →CCA→ICA | Conservative | Death (rerupture) |

| 3 | Yamanaka et al. 3 | 1987 | 71/F | Arterio- sclerosis | Begnning of the ICA | SAH | No | ECA→ICrA | Conservative | Death (rerupture) |

| 4 | Ishibashi et al. 10 | 1993 | 63/M | Arterio- sclerosis | Left cavernous sinus part of the ICA, right beginning of the ICA | Hydrocephalus | No | No | VP shunt+ Conservative | Good Recovery |

| 5 | Konishi et al. 11 | 1998 | 39/F | Arterio- sclerosis | Begnning of the ICA | Thalamic hematoma | SCA+AICA+PICA | ECA→ICrA | Coiling (basilar apex aneurysm)+ Clipping (others) | Good Recovery |

| 6 | Meguro et al. 12 | 2008 | 62/F | Arterio- sclerosis | Begnning of the CCA | SAH | PCA | VA→ECA→ICA | Coiling assisted by balloon (BA aneurysm+others) | Good Recovery |

| 7 | Present case | 2010 | 69/F | Arterio- sclerosis | Begnning of the ICA | SAH | No | No | Coiling | Good Recovery |

Abbreviations: F, female; M, male; SAH, subarachnoid hemorrhage; BA, basilar apex; VA, vertebral artery; ECA, external carotid artery; ICA, internal carotid artery; ICrA, intracranial artery; CCA, common carotid artery

3.1 General information

1) Six patients (5 female, one male, aged 39 to 71 years old with a mean age of 55 years). 2) The causes of carotid artery occlusion included aortic inflammation in two cases and atherosclerosis in four cases. 3) Upon admission to hospital, there were 4 cases with SAH, one case with thalamic hemorrhage and one case with hydrocephalus.

3.2 Radiology features

1) Location of occlusions: the beginning part of the common carotid artery in 3 cases, the beginning part of the internal carotid artery in 2 cases, the cavernous sinus segment at left and beginning part at right of the internal carotid artery in one case. 2) Aneurysm: all cases were saccular; 3 cases single; 3 cases combined with aneurysms in other regions. 3) Collateral circulation: in 2 cases, the vertebral artery to the external carotid artery to anastomosis of the internal carotid artery; in one case, the subclavian artery to the common carotid artery to anastomosis of the internal carotid artery; in 2 cases, the external carotid artery to anastomosis of the intracranial artery; in one case, no anastomosis.

3.3 Treatment

(1) Basilar apex aneurysm: conservative treatment in 3 cases, clipping treatment by craniotomy in one case, and endovascular treatment in 2 cases; (2) Other concurrent aneurysms in the 3 cases: clipping in 2 cases, embolization in one case; (3) one case of hydrocephalus was treated with a ventriculoperitoneal shunt.

3.4 Treatment results

1) In the 3 cases of conservative treatment, 2 cases died of rupture, and the hydrocephalus case showed good prognosis; 2) The case treated by clipping showed good prognosis; (3) One case treated by embolization showed good prognosis; (4) One case treated by embolization of the basilar apex aneurysm and clipping to the concurrent aneurysm showed good prognosis.

4. Discussion

Bilateral carotid artery occlusion is rare but has gained increased attention due to the improvement in diagnostic techniques in recent years, especially in non-invasive imaging 13,14. Following the development of a bilateral carotid artery occlusion, the posterior circulation bears the brunt of the brain blood supply, increasing blood pressure as well as the risk of saccular aneurysms 2,3. The basilar artery supporting the whole brain blood flow under high pressure has made treatment relatively difficult 7.

Two cases of bilateral carotid artery occlusion with concurrent basilar apex aneurysm treated conservatively in the 1980's failed and led to patient deaths due to rerupture of the aneurysms 3,5. Even when the aneurysm is distant from the apex of the internal carotid artery and located in the posterior cerebral and communicating arteries, conservative therapy can fail 2. On the other hand, in craniotomy with clipping of these aneurysms the transient occlusion of the parent arteries on the cerebral perfusion could lead to serious detrimental results 3,6. In contrast to these two treatment modes, the endovascular approach developed in recent years has fewer risks and significantly less trauma to patients, as demonstrated in previous studies as well as the present study.

Occlusion of the bilateral internal and common carotid arteries can be caused by many factors, including atherosclerosis, arteritis, arterial inflammation surrounding the invasion, vascular muscle fiber dysplasia, arterial dissection, and radiotherapy injury 2,13,15. Atherosclerosis is the most common and typical cause. Atherosclerosis can occur at the point of bifurcation of the internal carotid artery, leading to chronic and progressive arterial stenosis. When the area is completely occluded, the artery appears as a “beak” shape on DSA images. The progression is quite slow and difficult to diagnose 16. In the present case, the data from radiology was as just described and evidence that the cause was atherosclerosis.

Aortic inflammation can also cause carotid artery occlusion, and aortitis mainly occurs in Asian women. It is likely to be involved with the aortic arch and its branches, resulting in bilateral carotid artery occlusion and finally the failure of blood flow through the internal carotid artery 17. This type of occlusion presents similar clinical syndromes as that caused by atherosclerosis, so it is also a possible diagnosis. However, DSA images can discriminate between the two cases: an occlusion at the beginning part of the internal carotid artery is likely to be caused by atherosclerosis, while the occlusion of the bilateral common carotid artery is likely aortitis. In the 6 cases reported in the literature, 4 were caused by atherosclerosis and 2 by aortitis.

The length of time required for occlusions in these arteries allows for the development of collateral circulation as an alternate source of intracranial blood supply, depending on the sites of occlusion 3,5,9-12. When the bilateral common carotid artery is occluded, there is no blood flow in either the external or internal carotid arteries. However, due to the downstream location of the occlusion the vertebral artery from the posterior circulation can form an anastomosis with the external carotid artery and supply blood flow to the internal carotid artery. This situation occurred in two of the three cases of common carotid artery occlusion we reviewed 9,12. In the other case the subclavian artery formed an anastomosis with the common carotid artery through opened muscular branches to supply the internal carotid artery.

When occlusion of the bilateral internal carotid artery occurs, the collateral changes differ from those described for the common carotid artery occlusion. In 7 cases of internal carotid artery occlusion with concurrent aneurysms, Yamanaka reported that in 6 cases the anastomosis to the internal carotid artery was mediated by the external carotid artery 3. This included the formation of anastomosis between the middle meningeal and intracranial arteries, the submandibular artery from the external carotid artery and the artery underlying the cavernous sinus, and the external carotid artery through the ophthalmic, anterior ethmoid, and intracranial arteries. The one other case lacked the formation of anastomosis. Of the 6 reports we reviewed, 2 of 3 cases with internal carotid artery occlusion showed similar results 3,11, while one case reported by Ishibashi et aldid not 10. The formation of anastomosis alleviates the hemodynamic changes caused by carotid artery occlusion, but the effect is limited and local blood pressure still increases and leads to the risk of basilar artery aneurysms.

The hemodynamic changes after bilateral internal carotid artery occlusion are similar to those in Moyamoya disease, in that the end of the carotid artery is occluded leading to the gradual accretion of a cerebral vascular network 18. In this situation, the basilar artery becomes the most important artery for brain blood supply and is more prone to apex aneurysms 19-22. This condition also occurs in bilateral internal carotid artery or common carotid artery occlusion with concurrent basilar apex aneurysm, as the risk of rupture is high.

The conservative treatment can result in death, as shown 3,5; therefore these patients should be treated quickly. In the literature reviewed, 3 patients who received craniotomy or intervention therapy showed good prognosis, indicating that both approaches were effective 11,23-25. However, with the relatively older technique of clipping it is dangerous to clip the artery carrying the aneurysm due to the high internal blood pressure 11,24,25. An alternative is the endovascular approach, which affects the surrounding structures less and the process is directly visualized by DSA during surgery, resulting in less damage to patients. It has therefore emerged as a leading treatment for aneurysms 19,21,22. The present study used coil embolization, as the aneurysm was regularly cystic but with a narrow neck, and the result was good with no recanalization.

The bilateral internal carotid and common carotid artery occlusion can also lead to aneurysm in other arteries other than the basilar artery. Three of the 6 cases we reviewed above showed such changes, including aneurysms of the posterior communicating, posterior cerebral, superior cerebellar, anterior inferior cerebellar, and posterior inferior cerebellar arteries 9,11,12. For such aneurysms combined aggressive treatment should be performed, but is more difficult. In these 3 cases, one used clipping for the basilar artery aneurysm and other aneurysms, one used embolization of the basilar apex aneurysm with clipping of the others, and one case used the balloon assisted technique for embolization of the basilar apex and other aneurysms. Taken together, the data show that endovascular treatment is effective for these aneurysms as well.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, the basilar apex aneurysm caused by bilateral internal carotid artery and common carotid artery occlusion can be effectively treated by the endovascular approach. Concurrent aneurysms of other arteries can be treated simultaneously in the same technique.

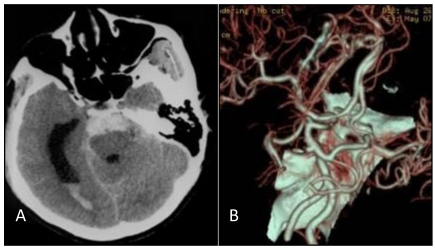

Figure 1.

A: Head CT scan shows that the hemorrhage was localized on the pontine cistern and interpeduncular cistern, extending to the right of the ambient cistern, into the posterior horn of the right ventricle. The patient was diagnosed with subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH). B: Head CT angiograph shows mound-like protuberances at the apex of the basilar artery with a diameter of 3.2 mm, no signal at the bilateral internal carotid artery, and bilateral posterior communicating artery supplying the circulation.

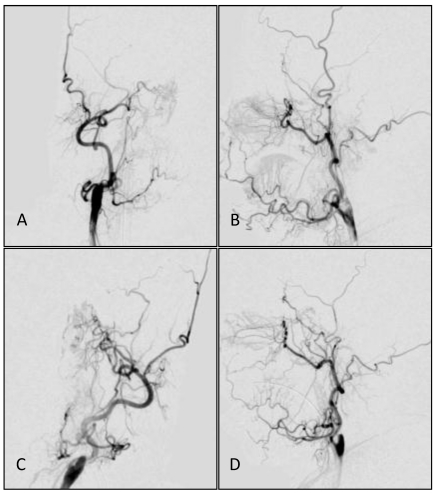

Figure 2.

Common carotid artery DS angiographs: occlusion at the beginning of internal carotid artery, with the remaining external carotid artery. No formation of anatomosis between the external carotid artery and intracranial vessels is observed. A, B: The right common carotid artery; C,D: The left common carotid artery.

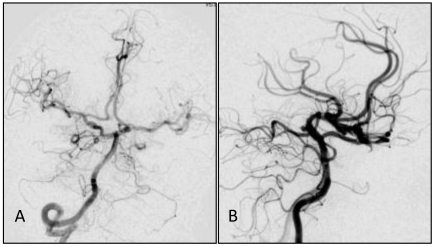

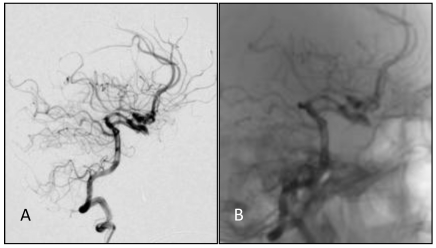

Figure 3.

A,B: Angiograph of the vertebral artery showing developed posterior circulation with blood supply through the bilateral posterior communicating artery. No delay was observed in the anterior circulation angiograph, and from (B) a basilar apex aneurysm of about 3.2 mm could be observed.

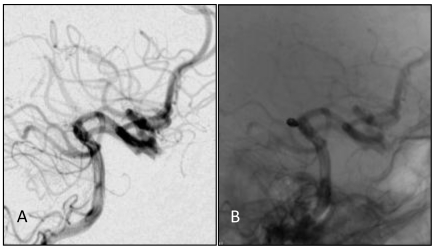

Figure 4.

A, B: DS angiographs taken after the aneurysm coil embolization. The aneurysm with dense embolization is not seen.

Figure 5.

A,B: One year after embolizing the aneurysm with the endovascular approach, embolization was still in good condition, without recanalization.

References

- 1.Shibuya T, Hayashi N. A case of posterior cerebral artery aneurysm associated with idiopathic bilateral internal carotid artery occlusion: case report. Surg Neurol. 1999;52:617–22. doi: 10.1016/s0090-3019(99)00134-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Araki T, Fujiwara H, Yasuda T. et al. A case of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage associated with bilateral common carotid artery occlusion. No Shinkei Geka. 2002;30:853–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yamanaka C, Hirohata T, Kiya K. et al. Basilar bifurcation aneurysm associated with bilateral internal carotid occlusion. Neuroradiology. 1987;29:84–8. doi: 10.1007/BF00341047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kazumata K, Terasaka S, Ishikawa T. et al. Ruptured P1-2 junction aneurysm associated with bilateral agenesis of the internal carotid artery. No Shinkei Geka. 2008;36:523–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Masuzawa T, Shimabukuro H, Sato F. et al. The development of intracranial aneurysms associated with pulseless disease. Surg Neurol. 1982;17:132–6. doi: 10.1016/s0090-3019(82)80041-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ito M, Sato K, Tsuji O. et al. Multiple aneurysms associated with bilateral carotid occlusion and venous angioma: surgical management risk-case report. J Clin Neurosci. 1994;1:62–8. doi: 10.1016/0967-5868(94)90013-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pierot L, Cognard C, Ricolfi F. et al. Immediate Anatomic Results after the Endovascular Treatment of Ruptured Intracranial Aneurysms: Analysis in the CLARITY Series. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2010;31:907–11. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A1954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Molyneux AJ, Kerr RS, Yu LM. et al. International Subarachnoid Aneurysm Trial (ISAT) Collaborative Group. International subarachnoid aneurysm trial (ISAT) of neurosurgical clipping versus endovascular coiling in 2143 patients with ruptured intracranial aneurysms: a randomised comparison of effects on survival, dependency, seizures, rebleeding, subgroups, and aneurysm occlusion. Lancet. 2005;366:809–17. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67214-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kumagai Y, Sugiyama H, Nawata H. et al. Two cases of pulseless disease with cerebral aneurysm (author's transl) No Shinkei Geka. 1981;9:611–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ishibashi A, Yokokura Y, Kojima K. et al. Acute obstructive hydrocephalus due to an unruptured basilar bifurcation aneurysm associated with bilateral internal carotid occlusion--a case report. Kurume Med J. 1993;40:21–5. doi: 10.2739/kurumemedj.40.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Konishi Y, Sato E, Shiokawa Y. et al. A combined surgical and endovascular treatment for a case with five vertebro-basilar aneurysms and bilateral internal carotid artery occlusions. Surg Neurol. 1998;50:363–6. doi: 10.1016/s0090-3019(97)00282-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meguro T, Tanabe T, Muraoka K. et al. Endovascular treatment of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage associated with bilateral common carotid artery occlusion. Interv Neuroradiol. 2008;14:447–52. doi: 10.1177/159101990801400411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fukumitsu R, Yoshida K, Sadamasa N. et al. Strategy for revascularization of chronic carotid occlusion with contralateral carotid stenosis. No Shinkei Geka. 2010;38:139–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bain M, Hussain MS, Gonugunta V. et al. Indirect reperfusion in the setting of symptomatic carotid occlusion by treatment of bilateral vertebral artery origin stenoses. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2010;19:241–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2009.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tavares A, Caldas JG, Castro CC. et al. Changes in perfusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging after carotid angioplasty with stent. Interv Neuroradiol. 2010;16:161–9. doi: 10.1177/159101991001600207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.AbuRahma AF, Copeland SE. Bilateral internal carotid artery occlusion: natural history and surgical alternatives. Cardiovasc Surg. 1998;6:579–83. doi: 10.1016/s0967-2109(98)00072-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sugino F, Takagi T, Fuse T. et al. Carotid artery reconstruction with a synthetic graft for aortitis syndrome. J Clin Neurosci. 1999;6:160–1. doi: 10.1016/s0967-5868(99)90085-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Komiyama M. Moyamoya Disease is a Progressive Occlusive Arteriopathy of the Primitive Internal Carotid Artery. Interv Neuroradiol. 2003;9:39–45. doi: 10.1177/159101990300900105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arita K, Kurisu K, Ohba S. et al. Endovascular treatment of basilar tip aneurysms associated with moyamoya disease. Neuroradiology. 2003;45:441–4. doi: 10.1007/s00234-003-0997-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kawaguchi S, Sakaki T, Morimoto T. et al. Characteristics of intracranial aneurysms associated with moyamoya disease. A review of 111 cases. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1996;138:1287–94. doi: 10.1007/BF01411057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Massoud TF, Guglielmi G, Viñuela F. et al. Saccular aneurysms in moyamoya disease: endovascular treatment using electrically detachable coils. Surg Neurol. 1994;41:462–7. doi: 10.1016/0090-3019(94)90008-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bhattacharjee AK, Tamaki N, Minami H. et al. Moyamoya disease associated with basilar tip aneurysm. J Clin Neurosci. 1999;6:268–71. doi: 10.1016/s0967-5868(99)90522-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tasker RR. Ruptured berry aneurysm of the anterior ethmoidal artery associated with bilateral spontaneous internal carotid artery occlusion in the neck. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1983;59:687–91. doi: 10.3171/jns.1983.59.4.0687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kagawa K, Ezura M, Shirane R. et al. Intraaneurysmal embolization of an unruptured basilar tip aneurysm associated with moyamoya disease. J Clin Neurosci. 2001;8:462–4. doi: 10.1054/jocn.2000.0806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ito M, Sato K, Tsuji O. et al. Multiple aneurysms associated with bilateral carotid occlusion and venous angioma: surgical management risk-case report. J Clin Neurosci. 1994;1:62–8. doi: 10.1016/0967-5868(94)90013-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]