Abstract

Although DNA flexibility is known to play an important role in DNA–protein interactions, the importance of protein flexibility is less well understood. Here, we show that protein dynamics are important in DNA recognition using the well-characterized human papillomavirus (HPV) type 6 E2 protein as a model system. We have compared the DNA binding properties of the HPV 6 E2 DNA binding domain (DBD) and a mutant lacking two C-terminal leucine residues that form part of the hydrophobic core of the protein. Deletion of these residues results in increased specific and non-specific DNA binding and an overall decrease in DNA binding specificity. Using 15N NMR relaxation and hydrogen/deuterium exchange, we demonstrate that the mutation results in increased flexibility within the hydrophobic core and loop regions that orient the DNA binding helices. Stopped-flow kinetic studies indicate that increased flexibility alters DNA binding by increasing initial interactions with DNA but has little or no effect on the structural rearrangements that follow this step. Taken together these data demonstrate that subtle changes in protein dynamics have a major influence on protein–DNA interactions.

INTRODUCTION

The recognition of specific DNA sequences by proteins is required for gene transcription, DNA replication and all other processes that involve the manipulation of DNA. Although the structural and mechanistic properties of many protein–DNA complexes have been studied in fine detail, we still lack a thorough understanding of the role of protein and DNA flexibility in sequence recognition. The papillomavirus E2 proteins have provided several important insights into specific and non-specific DNA binding and the role of DNA flexibility in protein–DNA interactions (1,2). The E2 proteins from several human papillomavirus (HPV) types including HPV 6, 16 and 18 have been studied in molecular detail as has the bovine papillomavirus (BPV) E2 protein (1).

The E2 proteins comprise an N-terminal transcription regulatory domain and a C-terminal DNA binding domain (DBD) separated by a spacer or hinge region that is thought to be largely unstructured (3). The DBD functions as an obligate dimer forming monomers only after denaturation (4). The DBD binds to inverted repeats with the consensus sequence:

−7654321

5′ -AACCGNNNNCGGTT-3′

3′ -TTGGANNNNGCCAA-5′

+1234567

where the 5′-AACCG-3′ motif and its symmetrically related inverted repeat 5′-CGGTT-3′ represent the core E2 binding site and N4 represents a 4 bp spacer of variable sequence (5,6). The two subunits of the DBD form a β-barrel that supports two pairs of surface exposed α-helices (7). One pair of symmetrically positioned α-helices make sequence-specific contacts with the exposed edges of core E2 binding site base pairs in two successive major grooves of the DNA (7). Although the DBD does not contact the base pairs in the spacer region there can be electrostatic interactions between a surface exposed loop that links the β2- and β3-strands in the protein and the DNA backbone, and the nature of the spacer region has a profound influence on the ability of E2 proteins to bind DNA (8). The HPV 16 DBD binds with high affinity to E2 sites that contain a spacer sequence rich in A:T base pairs but binds with much lower affinity to E2 sites that contain a spacer sequence rich in G:C base pairs (8,9). This preference for E2 sites with an A:T rich spacer sequence is even more marked for the HPV 6 E2 protein (10). In contrast, the BPV E2 protein shows little preference for an A:T rich spacer sequence (8). This indirect readout of the spacer sequence is believed to arise at least in part from differences in the intrinsic conformational freedom of different DNA sequences (11,12). E2 sites with an A:T rich spacer are intrinsically preferentially bent towards the major groove whereas those with a G:C rich spacer sequence are predominantly unbent (11,12). In both crystallographic and solution studies of E2-DNA complexes, the bound DNA is bent between 30° and 50° from linear and bending facilitates penetration of the DNA recognition helices into the DNA major grooves (5,7,13). The intrinsic DNA bending associated with E2 sites with an A:T rich spacer is presumed to be entropically favourable for complex formation (10). In addition, DNA bending results in wrapping of the DNA around the protein allowing extended contacts to be formed (5,10).

Conformational changes within the E2 DBD also occur on complex formation (14–16). In the BPV E2-DNA complex, the β2/β3-loop which is unstructured and presumed mobile in the free protein, adopts a discrete conformation in contact with DNA backbone phosphates in the spacer region (7). Similarly, the HPV 16 E2 β2/β3-loop makes electrostatic contacts with the phosphate backbone in the spacer region upon complex formation (17). This suggests that these proteins undergo localized folding or loop rearrangements that favour DNA binding. The relative orientation of the recognition helices from these proteins also change on complex formation (2,13,18). However, this re-orientation is not observed for the HPV 6 E2 recognition helices and the HPV 6 E2 β2/β3-loop is ordered in both the presence and absence of bound DNA (10,13). Recent NMR and molecular dynamics studies have indicated that in solution both the HPV 16 and BPV proteins contain a flexible β2/β3-loop and in the case of the BPV protein, there is flexibility in the loop connecting α2–β4 and in the β-barrel. These differences in dynamics have been suggested to be the basis for differences in protein adaptability and hence DNA recognition (15,19,20). The HPV 6 β-barrel is formed around a network of hydrophobic side chains that includes two C-terminal leucine residues, L367 and L368 (Figure 1A) that are not present in most other E2 proteins (6). We hypothesized that removal of these residues (and hence four side-chains from the hydrophobic core of the DBD) would alter the dynamics within the E2 dimer and thereby modulate the DNA binding activity of this protein. Here, we show that a mutated protein lacking these residues has increased flexibility and increased affinity for both specific and non-specific DNA.

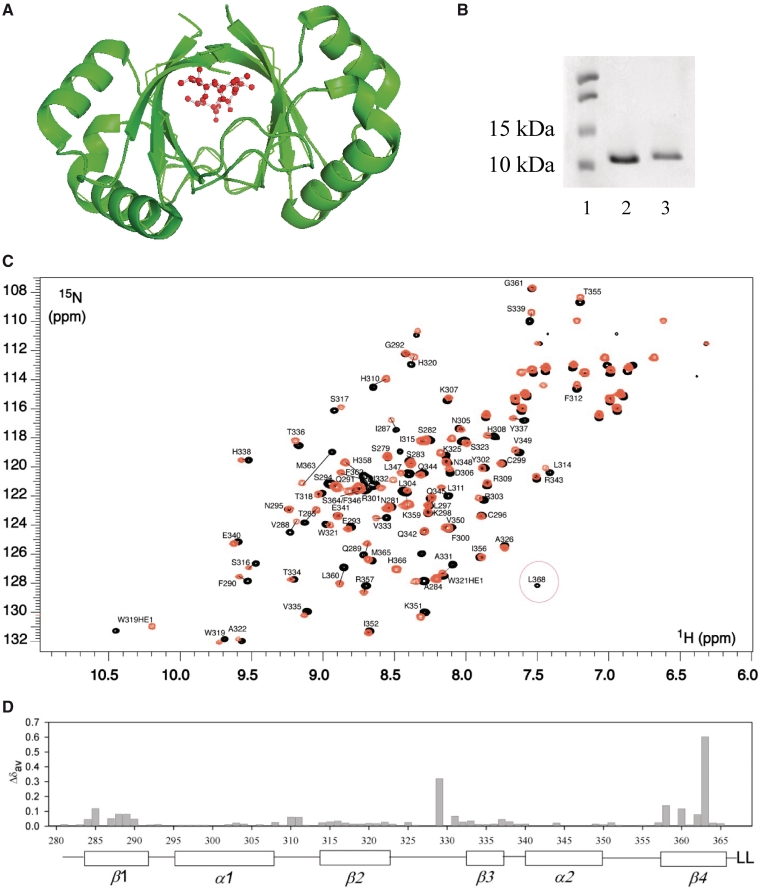

Figure 1.

Biochemical and NMR characterization of HPV 6 E2 and E2ΔLL. (A) The HPV 6 E2 β-barrel from PDB 1R8H visualized using PyMol (41). Residues L367 and L368 are highlighted in red. (B) Samples of the purified HPV 6 E2 and HPV 6 E2ΔLL proteins were analysed by SDS–PAGE. The sizes of the markers used are indicated to the left of the gel. (C) Comparison of 1H-15N HSQC spectra of the 6 E2 proteins. The 1H-15N spectra of 6 E2 (black) and E2ΔLL (orange) are superimposed. Peaks that show large chemical shift perturbations between the two forms are connected with a line. (D) Chemical shift perturbations (Δδav) between 6 E2 and E2ΔLL plotted versus sequence number.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids used in this study

Plasmid pKK223-3-HPV 6 E2 expresses the HPV 6 E2 DBD (amino acids 281–368) and has been described previously (10). To produce the truncated HPV 6 E2ΔLL protein the C-terminal leucine residues in the HPV 6 E2 DBD (amino acids L367 and L368) were deleted by the introduction of a stop codon at position 367 using a QuickChange mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Protein labelling and purification

The unlabelled E2 DBD proteins used in this study were expressed in Escherichia coli XL1 blue cells and purified to homogeneity as described previously (10). In brief, the proteins were purified over an SP-sepharose column followed by further fractionation on a MonoS 5/5 column and final purification using a Heparin column. Bound proteins were eluted using a 0.0–1.5 M NaCl gradient. The purified proteins were dialysed against PBS containing 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −70°C until required. Protein concentration was determined from the OD280nm using the molar extinction coefficient and activity was determined using gel retardation assays. Proteins uniformly labelled with 15N or 15N and 13C were produced by growing the bacteria in M9 minimal media containing 15NH4Cl or 15NH4Cl and 13C glucose as the sole nitrogen and carbon sources. The labelled proteins were purified as above.

NMR

Sample conditions and assignment

Triple resonance NMR data were acquired at 30°C on a Varian INOVA spectrometer operating at 600 MHz with a room temperature probe. Samples were typically 1–2 mg/ml (0.1–0.2 mM) and buffer conditions were 50 mM NaAc, 25 mM KCl, 5 mM DTT, pH 5.6. Standard triple resonance experiments [HNCA, HN(CO)CA, HNCACB, CBCA(CO)NH, HNCO] were collected for backbone assignment of the wild-type HPV 6 E2. Assignment of the HPV 6 E2ΔLL were completed using a sample of uniformly 15N-labelled protein and assignments made using 15N-edited NOESY and TOCSY three-dimensional (3D) data sets. The chemical shift perturbation was calculated according to the equation: Δδav = {0.5[Δδ (1HN)2 + (0.2 Δδ (15N))2]}1/2 (21).

Relaxation studies

15N-T1, T2 and 1H-15N NOE relaxation data were acquired on a Varian VNMRS 600 MHz spectrometer equipped with a salt-tolerant cryogenically cooled probe-head (22). Protein concentrations were 1–2 mg/ml and all spectra were recorded at 30°C and sensitivity was maximized by recording spectra in 3 × 6 mm S-tubes. Buffer conditions were identical to those used in the chemical shift assignment. T1 delays of 11.1, 33.3, 55.5, 111.0, 199.8, 333, 499.5, 666, 832.5ms and T2 delays of 16.6, 33.2, 49.9, 66.6, 83.2, 99.8, 116.5, 133.1, 149.8, 166.4 ms were utilized. 1H-15N NOEs were measured by recording HSQC spectra with and without proton saturation. The spectra without NOE were recorded with delays of 5 s and spectra with NOE used 3 s of proton saturation and 2 s of delay to give the same total delay of 5 s between transients. T1 and T2 values were obtained by non-linear least squares fits of the amide cross peak intensities to a two-parameter exponential decay. Uncertainties in the T1 and T2 values were estimated from non-linear least squares fits. Uncertainties in the NOE values were estimated from the base plane noise in 2D 1H-15N HSQC spectra recorded with and without proton saturation according to Farrow et al. (22).

Model free analysis of the relaxation data was performed using the two-time-scale Lipari–Szabo spectral density [Equation (1)] (23,24).

| (1) |

where τc is the overall correlation time (isotropic tumbling is assumed), S2 is the order parameter, τ−1 = τc−1 + τe−1, and τe is the effective correlation time describing fast internal motions. Model free parameters were obtained from the experimental data by minimizing a target function describing the differences between experimental relaxation parameters and relaxation parameters calculated from the spectral density functions for the 15N-T1, T2 and 1H-15N NOE values (23,24). These included  and

and  and a two-time scale model were fitted to the data (25). All models were fitted using the programme Modelfree 4.15 (26).

and a two-time scale model were fitted to the data (25). All models were fitted using the programme Modelfree 4.15 (26).

For H/D exchange experiments, freshly lyophilized samples of 15N-labelled HPV 6 E2 and E2ΔLL were dissolved in 99.98% D2O and the same buffer used for assignment and structural studies. The concentration of E2ΔLL (∼1.0 mg/ml) was estimated to be about twice that of HPV 6 E2. A series of 1H-15N HSQC spectra were recorded within 5–7 min of dissolving in buffer. A total of 18 spectra were recorded (128 complex points in t1, four scans) over the first 180 min, followed by 64 spectra (128 complex points, eight scans) over the following 21 h, followed by a series of 36 spectra (12 scans) over the final 24 h. The spectra were processed in NMRPipe and multiple spectra picked using the programme Analysis (27). Amide exchange rates were calculated by fitting the decay of amide intensities with a single-exponential decay curve for well-resolved peaks in the spectra.

Gel retardation assays

Oligonucleotides with consensus E2 binding sites and A:T rich or G:C rich spacer sequences used in this work are shown below; the E2 core sites are underlined and the central spacer regions are highlighted in bold. Only the top strands are shown for clarity:

| AT | 5′-ACTAAGGGCGTTGAACCGAATTCGGTTAGTATAAAAGCAG-3′ |

| GC | 5′-ACTAAGGGCGTTGAACCGCCGGCGGTTAGTATAAAAGCAG-3′ |

The non-specific DNAs used in the work were a 195 bp SphI-BamHI DNA fragment corresponding to sequences from −3913 to −3718 relative to the start of exon 1 in the human Vegf promoter and the short non-specific oligonucleotide shown below:

| NS | 5′-AGCTTCTGGGAAGCAATTAAAAAATGGCTCGAGCT-3′ |

Single-stranded oligonucleotides (200 ng) were labelled with [γ32]P ATP using T4 polynucleotide kinase. Double-stranded labelled DNA was then prepared by annealing complementary oligonucleotides by cooling from 90°C to 20°C over 4 h. The 195 bp non-specific DNA fragment was labelled with [α32]P ATP using Klenow enzyme. Unincorporated ATP was removed using Micro Bio-Spin 6 columns (Bio-Rad) and labelled DNAs (5000 cpm) were incubated with purified proteins in 20 mM HEPES pH 7.9, 150 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 5 mM dithiothreitol, 0.1% Nonidet P40, 10% glycerol and 0.5 µg/µl bovine serum albumin. After 20 min at 20°C free and bound labelled DNA were resolved on 6% non-denaturing polyacrylamide gels run in 1× TBE. The DNA was visualized and quantified using a PhosphorImager with Molecular Dynamics ImageQuant software (version 3.3). All experiments were repeated at least five times. The apparent equilibrium constant (Keq(apparent)) was obtained using the equation below [Equation (2)] and Grafit4 software (Erithacus Software, Staines, UK):

| (2) |

Since the concentration of labelled DNA (<100 pM) is much lower than Keq the apparent equilibrium constant is equal to the protein concentration at half maximum DNA binding.

Solution-binding studies

Stopped-flow kinetic analysis experiments were performed as described previously (13) by monitoring tryptophan fluorescence at 320 nm after excitement at 285 nm (Applied Photophysics SpectraKinetic Monochromator and Workstation). The concentration of E2 was kept constant at either 0.05, 0.2 or 0.5 μM and the concentration of the A:T rich oligonucleotide was varied from 0.5- to 20-fold protein concentration. The experiments were performed in 50 mM sodium phosphate, 150 mM NaCl and 2 mM dithiothreitol and the stopped flow chamber was kept at a constant temperature of 25°C. Around 25 sets of data were obtained for each condition. The averaged data were analysed using Grafit4 (Erithacus Software, Staines, UK) and fitted to a double exponential curve with offset according to the equation [Equation (3)]:

| (3) |

where A1 = amplitude 1, A2 = amplitude 2, k1 = fast rate, k2 = slow rate and c = offset.

The rates obtained from the double exponential curve were plotted against the DNA concentration and fitted to a straight line fit for both the slow and the fast rate.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The HPV 6 DBD is rigid in solution

We truncated the HPV 6 E2 DBD by removing the two C-terminal leucine residues L367 and L368. The truncated HPV 6 E2ΔLL protein was successfully produced in bacteria and purified to homogeneity (Figure 1B). The truncated protein was readily soluble suggesting that it is properly folded. To compare the rigidity of the wild-type and mutated DBDs, we aimed to study the backbone 15N relaxation of both proteins. We therefore produced 15N and 15N/13C-labelled HPV 6 E2 and 15N-labelled E2ΔLL for dynamics and chemical shift assignment. The 1H-15N HSQC spectra of both HPV 6 E2 and E2ΔLL show good chemical shift dispersion and a single set of resonances (Figure 1C) corresponding to the dimeric species at a range of protein concentrations. This is as expected since high concentrations of urea or other denaturants are required to form monomeric E2 species (4,5,28) and under the conditions used here these proteins form only dimers. The backbone chemical shifts of 6 E2 were assigned using standard triple resonance experiments and transferred to the E2ΔLL mutant using 15N-edited NOESY and TOCSY 3D data sets. Complete assignments could not be made for residues H328 through to H330 in the latter half of the β2/β3-loop due to peak broadening and a lack of correlations in the triple resonance spectra. Similarly missing assignment data was reported over most of the β2/β3-loop for the related HPV 16 DBD (29).

A superposition of the 1H-15N HSQC spectra for 6 E2 and E2ΔLL is shown in Figure 1C. The majority of peaks show identical or very similar chemical shifts in both forms of the protein. Therefore despite the deletion of hydrophobic core residues, the overall structure of the protein appears to have remained intact. Leucine 368, which is clearly resolved and circled in Figure 1C, has no corresponding peak in the mutant form as expected. Only approximately 15 backbone residues show chemical shift perturbations (Δδav) >0.5 ppm (21) and these are predominantly residues on β1 and β4 that are in direct contact or adjacent in the structure to the leucine deletion (Figure 1D). F362 and M363 both show significant chemical shift changes that may result from some loss of structure in β4, which in turn appears to affect residues 285–290 in β1. The remainder of the larger chemical shift perturbations reside in the β2/β3-loop that packs against the leucine residues in the wild-type protein and which also makes contacts with β1.

The reasonable chemical shift dispersion of the E2 spectra allowed the backbone amide relaxation rates to be measured for 59 residues in wild-type E2 (69.4% of residues not including prolines or the N-terminal N279) and 66 residues in E2ΔLL (79.5%). The overall correlation time was determined independently for both E2 and E2ΔLL at 600 MHz. Initially an optimal  was calculated on a per residue basis by minimizing the difference between the experimental and the calculated T1, T2 and NOE using the isotropic spectral density function given by Equation (1). Once optimum

was calculated on a per residue basis by minimizing the difference between the experimental and the calculated T1, T2 and NOE using the isotropic spectral density function given by Equation (1). Once optimum  values were calculated for each residue, an optimum average

values were calculated for each residue, an optimum average  was calculated.

was calculated.  was determined to be 9.9 ns and was identical for both proteins.

was determined to be 9.9 ns and was identical for both proteins.

From the measured T1, T2 and NOE relaxation data, parameters that describe the internal motions of 6 E2 were determined using the model-free analysis under the assumption of isotropic tumbling (23,24). Appropriate models of spectral density functions were selected for each residue. These included  and

and  models and a two-time scale model (25,30) as defined in the ‘Materials and Methods’ section. T1, T2 and NOE data are shown in Figure 2A–C. In general, there is good agreement of relaxation parameters over equivalent residues with the exception of residues at the N- and C-termini and in the β2/β3-loop. The backbone 15N relaxation data were interpreted with the Lipari–Szabo method (23,24) that uses a model independent formalism and is expressed in terms of a generalized order parameter S2 that describes the degree of spatial restriction of a bond vector. Values of S2 >0.9 are indicative of essentially static structures (on the nanosecond timescale), whereas lower values generally indicate increasing mobility. Relaxation data were fitted with a number of motional models and the S2 determined for each residue (Figure 2D). For those residues that did not fit well to the

models and a two-time scale model (25,30) as defined in the ‘Materials and Methods’ section. T1, T2 and NOE data are shown in Figure 2A–C. In general, there is good agreement of relaxation parameters over equivalent residues with the exception of residues at the N- and C-termini and in the β2/β3-loop. The backbone 15N relaxation data were interpreted with the Lipari–Szabo method (23,24) that uses a model independent formalism and is expressed in terms of a generalized order parameter S2 that describes the degree of spatial restriction of a bond vector. Values of S2 >0.9 are indicative of essentially static structures (on the nanosecond timescale), whereas lower values generally indicate increasing mobility. Relaxation data were fitted with a number of motional models and the S2 determined for each residue (Figure 2D). For those residues that did not fit well to the  models, alternative models were assumed (i.e.

models, alternative models were assumed (i.e.  and the two-time-scale model) according to the criteria of Farrow et al. (22).

and the two-time-scale model) according to the criteria of Farrow et al. (22).

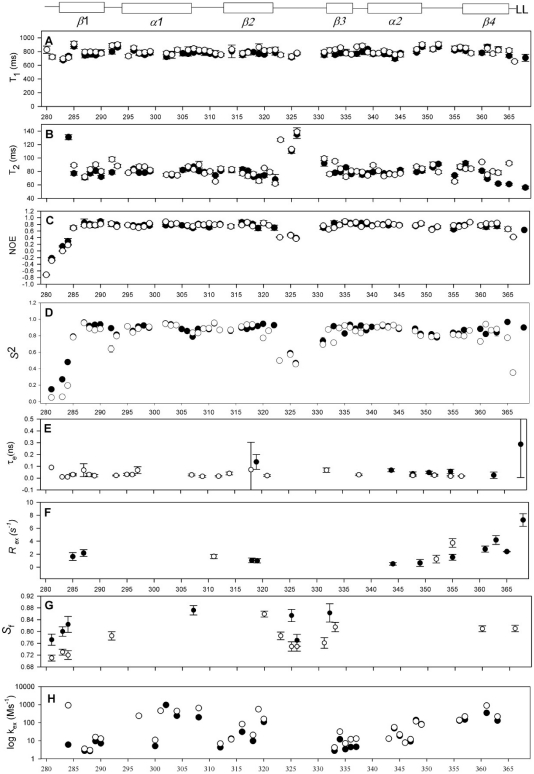

Figure 2.

1H-15N NMR relaxation data and graphical representation of dynamics parameters from the Lipari and Szabo model free analysis. Elements of secondary structure for 6 E2 are shown above the graphs. Plots of (A) 15N-T1, (B) 15N-T2 and (C) NOE at 600 MHz for 6 E2 (filled circles) and E2ΔLL (open circles) are shown. Where data is not given for a residue the values of 15N-T1, 15N-T2 and NOE could not be determined due to resonance overlap. (D) Plot of the dynamic order parameters derived from the Lipari and Szabo model free analysis (23,24), (E) internal correlation times (τe), (F) conformational exchange terms (Rex), (G) two-time-scale (τs) and (H) Amide exchange rates (106 s−1). Where data is not shown no rate could be measured due to the rate being too fast to observe or resonance overlap.

Consistent with previous crystal structures, the wild-type protein shows remarkably little flexibility as seen by the majority of residues having S2 values of >0.85 (Figure 2D–G). The majority of residues within the core secondary structure of 6 E2 could be fitted to the simplest  model indicative of a highly ordered protein fold. There are, however, three regions of the protein that show markedly different motional properties. The N-terminus, as in many proteins, shows a degree of increased flexibility and these residues only tended to fit with the two-time-scale model. Second, the β2/β3-loop, that is ordered in the 6 E2 DBD crystal structures (although with higher than average temperature factors), appears partially disordered in solution, as evidenced by pronounced reductions in S2 values for loop residues and fitting throughout the loop to the two-time-scale model in the sub-nanosecond timescale (Figure 2G). Several loop residues are missing data due to the weak 1H-15N signals observed in this region and the presence of two proline residues that are not detectable due to the absence of amide protons. These data suggest that there may be some ordering of the 6 E2 β2/β3-loop upon DNA binding, although the temperature factors indicate that some disorder persists in the complex. Finally the C-terminus which is buried in the hydrophobic core of the protein does not show reduced S2 values as seen in many protein dynamics studies with flexible C-termini. However, the reduced T2 values measured for residues 361–368 requires the

model indicative of a highly ordered protein fold. There are, however, three regions of the protein that show markedly different motional properties. The N-terminus, as in many proteins, shows a degree of increased flexibility and these residues only tended to fit with the two-time-scale model. Second, the β2/β3-loop, that is ordered in the 6 E2 DBD crystal structures (although with higher than average temperature factors), appears partially disordered in solution, as evidenced by pronounced reductions in S2 values for loop residues and fitting throughout the loop to the two-time-scale model in the sub-nanosecond timescale (Figure 2G). Several loop residues are missing data due to the weak 1H-15N signals observed in this region and the presence of two proline residues that are not detectable due to the absence of amide protons. These data suggest that there may be some ordering of the 6 E2 β2/β3-loop upon DNA binding, although the temperature factors indicate that some disorder persists in the complex. Finally the C-terminus which is buried in the hydrophobic core of the protein does not show reduced S2 values as seen in many protein dynamics studies with flexible C-termini. However, the reduced T2 values measured for residues 361–368 requires the  models and a contribution from slower (µs–ms) exchange motions (Rex, Figure 2F). The size of the Rex term increases significantly towards the C-terminus.

models and a contribution from slower (µs–ms) exchange motions (Rex, Figure 2F). The size of the Rex term increases significantly towards the C-terminus.

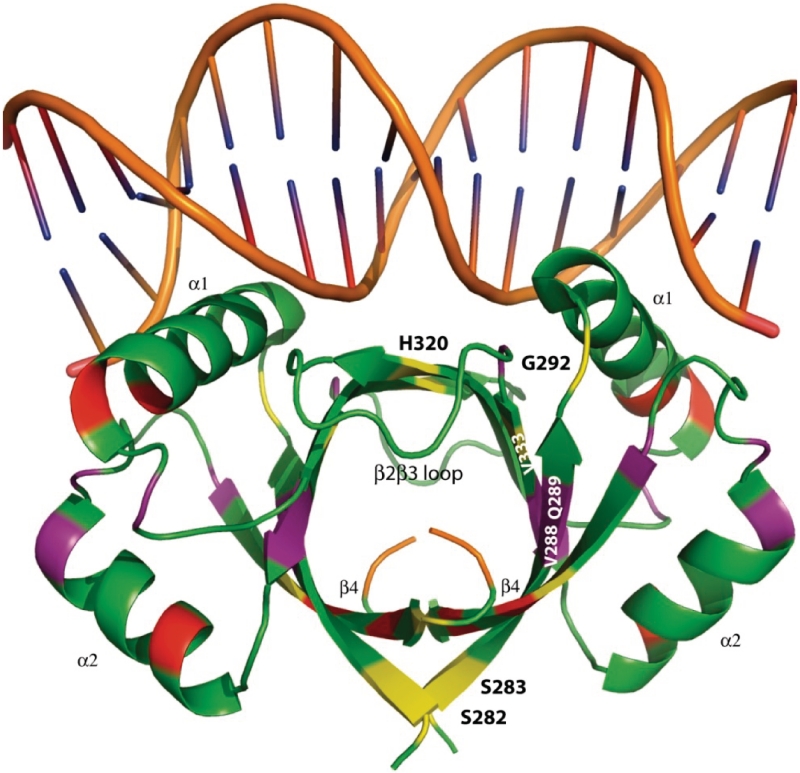

Analysis of the E2ΔLL relaxation data reveals that many of the S2 values over the secondary structure could only be satisfactorily fit with the  model that incorporates fast motions and in general the order parameters are marginally lower (Figure 2D). Figure 3 shows the crystal structure of the DNA bound form of 6 E2 (13). Residues in E2ΔLL that show a large reduction in S2 (>0.1) compared to 6 E2 are shown in yellow while changes from 0.05 to 0.1 are shaded in purple. Conversely, residues that that are more ordered in E2ΔLL are shaded in red. The largest concentration of change, which shows an increase in flexibility, is centred around residues that can no longer pack against the deleted terminal leucine residues at the core of the dimeric barrel. The C-terminus, for example, shows a loss of the slow conformational exchange observed in wild-type 6 E2 being replaced instead with lower values of S2 (assuming approximately the same overall topology and monomer–dimer dissociation constant these are most likely not due to anisotropic motion or monomer–dimer exchange, respectively). Similarly the N-terminus (i.e. S282 and S283) and central region (i.e. V288 and Q289) of the β-barrel shows increased flexibility, for example both show reduced S2 values (Figure 3). Along the sequence length several residues show notably reduced S2 values, including G292, H320 and V333. G292 fits a two-time scale model indicative of an increase in sub-nanosecond (but not picosecond) motions and importantly connects β1 to the DNA binding helix α1. Similarly H320 and V333 that flank the β2/β3-loop both show an increase in sub-nanosecond motions indicating that the flexibility in this loop now extends to incorporate these residues at the edges of the β-barrel.

model that incorporates fast motions and in general the order parameters are marginally lower (Figure 2D). Figure 3 shows the crystal structure of the DNA bound form of 6 E2 (13). Residues in E2ΔLL that show a large reduction in S2 (>0.1) compared to 6 E2 are shown in yellow while changes from 0.05 to 0.1 are shaded in purple. Conversely, residues that that are more ordered in E2ΔLL are shaded in red. The largest concentration of change, which shows an increase in flexibility, is centred around residues that can no longer pack against the deleted terminal leucine residues at the core of the dimeric barrel. The C-terminus, for example, shows a loss of the slow conformational exchange observed in wild-type 6 E2 being replaced instead with lower values of S2 (assuming approximately the same overall topology and monomer–dimer dissociation constant these are most likely not due to anisotropic motion or monomer–dimer exchange, respectively). Similarly the N-terminus (i.e. S282 and S283) and central region (i.e. V288 and Q289) of the β-barrel shows increased flexibility, for example both show reduced S2 values (Figure 3). Along the sequence length several residues show notably reduced S2 values, including G292, H320 and V333. G292 fits a two-time scale model indicative of an increase in sub-nanosecond (but not picosecond) motions and importantly connects β1 to the DNA binding helix α1. Similarly H320 and V333 that flank the β2/β3-loop both show an increase in sub-nanosecond motions indicating that the flexibility in this loop now extends to incorporate these residues at the edges of the β-barrel.

Figure 3.

Changes in protein flexibility in a truncated E2 DNA binding domain. The DNA bound form of the HPV 6 E2 DBD from PDB 2AYG visualized using PyMOL (41). The protein and DNA backbones are shown in green and brown, respectively. The C-terminal amino acids L367 and L368 are highlighted in orange. Protein residues that show reductions in S2 >0.1 are shown in yellow and reductions 0.05–0.1 are shown in purple. Increases of S2 >0.05 are shown in red.

To complement the relaxation studies we measured hydrogen/deuterium (H/D) exchange rates using 15N-labelled E2 and E2ΔLL (Supplementary Figure S1). In most cases, slow H/D exchange occurs when an amide proton is involved in a hydrogen bond and an increased exchange rate is observed upon localized or global protein unfolding. For both proteins, the amide exchange rates fell broadly into three categories, very fast, medium and slow (Supplementary Table S1 and Figure 2H). Very fast exchanging amides were not captured in either the 6 E2 or E2ΔLL H/D exchange experiments and appear as gaps in Figure 2H. These amides were almost all situated in the loops connecting the secondary structure elements but are regions that were well characterized by the relaxation data. ‘Medium’ amide exchange rates ranging from 10 to 1000 (106 s−1) were observed in helices α1 and α2 of both forms with comparable rates with the exception of F300, L304 and H308 that show 2- to 3-fold slower exchange in the wild-type. Overall, however, this agrees with the relaxation data that suggests that the stability of the helical elements shows little change between the proteins. The remaining slow exchanging amides from 1 to 10 (106 s−1) fall neatly throughout the first and third β-strands with the second β-strand showing a mixture of slow to fast rates. However, exchange rate increases are observed throughout the β-barrel for E2ΔLL. This broadly agrees with the dynamics data and suggests a more pervasive loss of amide protection than is suggested by the S2 values alone.

Both the relaxation and H/D exchange data probe the dynamics of 6 E2 and E2ΔLL over a wide range of timescales that reveal subtle changes in the mutant protein consistent with increased mobility. Overall this leads to the interpretation that—relative to the wild-type protein—E2ΔLL shows increased flexibility in both the β-barrel and longer range effects in the amino acids flanking the β2/β3-loop and connecting to the DNA binding helix (Figure 3). The wider dynamic changes are reminiscent of the global conformational changes that occur in the HPV 16 E2 DBD when this protein binds to DNA (15).

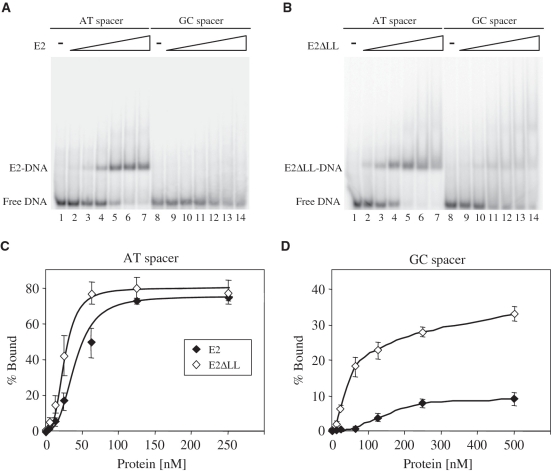

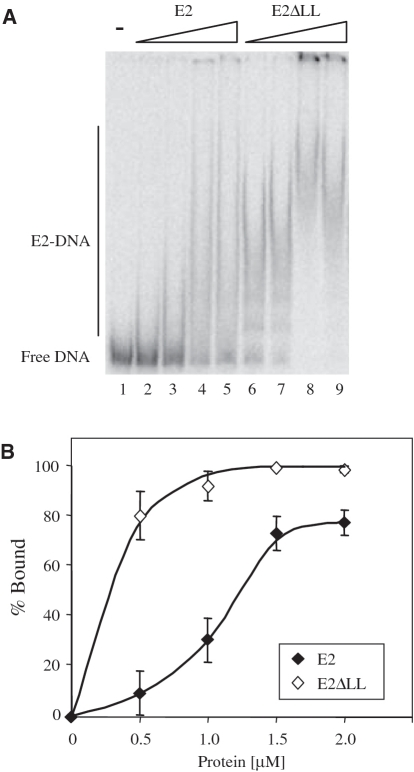

Increased protein flexibility correlates with increased DNA binding affinity

To compare quantitatively the DNA binding activity of the wild-type and mutated proteins, we performed gel retardation assays with labelled E2 sites containing either A:T rich or G:C rich spacer sequences (Figure 4A and B). As expected from previous experiments (8,10), 6 E2 binds to an E2 site with an A:T rich spacer to produce a retarded complex but binds very poorly to the same E2 site with a G:C rich spacer (Figure 4A). In contrast, the E2ΔLL protein is seen to bind significantly to both oligonucleotides, albeit with lower affinity to the site with a G:C rich spacer (Figure 4B). The amount of free and bound DNA at each protein concentration was determined in several independent experiments and binding curves fitted to the data (Figure 4C and D). These binding curves were used to determine the apparent equilibrium constant for each protein at these sites (Table 1). The wild-type HPV 6 E2 DBD protein binds to the A:T rich spacer site with an apparent equilibrium constant of 41±13 nM. This value is lower than that we have previously reported (10), a difference likely to be attributable to changes in the length of the oligonucleotides used in the assays. The E2ΔLL protein binds to the same A:T rich spacer site around 2-fold more tightly than the wild-type DBD, with an apparent equilibrium constant of 22±7 nM. The 6 E2 DBD binds to the G:C rich spacer site much less tightly than it does to the A:T rich spacer site and in this case the affinity is too low to be determined accurately using this method. Similarly, although it is apparent that E2ΔLL binds to the G:C rich spacer site with much higher affinity than the wild-type protein (Figure 4D), due to the weak binding it is not possible to accurately determine the affinity from these data. However, since E2ΔLL also shows increased binding to the A:T rich spacer site, these data suggest that increased protein flexibility has increased DNA binding affinity without greatly changing the preference for an A:T spacer sequence over a G:C spacer sequence.

Figure 4.

Specific DNA binding by the 6 E2 and E2ΔLL proteins. (A) A representative gel retardation experiment showing the binding of 6 E2 to labelled E2 binding sites with A:T rich or G:C rich spacer sequences. Lanes 1 and 8 contain no protein, lanes 2–7 contain 5, 12.5, 25, 62.5, 125 and 250 nM protein and lanes 9–14 contain 12.5, 25, 62.5, 125, 250 and 500 nM protein. Free and bound DNA were separated on a 6% polyacrylamide gel and visualized using a PhosphorImager. (B) A representative gel retardation experiment showing the binding of E2ΔLL to the labelled E2 binding sites from (A). Lanes 1 and 8 contain no protein, lanes 2–7 contain 5, 12.5, 25, 62.5, 125 and 250 nM protein and lanes 9–14 contain 12.5, 25, 62.5, 125, 250 and 500 nM protein. Free and bound DNA were separated and visualized as above. (C) A graph showing the binding of E2 proteins to the labelled E2 binding sites from (A). The amount of free and bound DNA was determined using a PhosphorImager and the percentage of labelled DNA bound {[bound labelled DNA/(bound labelled DNA + free labelled DNA)] × 100} is plotted against the amount of protein added. (D) A graph showing the binding of E2ΔLL to the labelled E2 binding sites from (A). Details as above.

Table 1.

Binding of E2 and E2ΔLL to specific and non-specific DNA

|

|

|

|---|---|---|

| E2 site A:T spacer | 41 ± 13 | 22 ± 7 |

| Non-specific DNA | 1203 ± 437 | 110 ± 25 |

| Specificityb | 29.4 | 5.0 |

aThe apparent equilibrium constant (Keq(apparent)) was obtained using the equation:

[boundDNA] = [maximum boundDNA] [protein]/([protein] + Keq(app))

When [DNA] is much less than the Keq, the apparent equilibrium constant is equal to the protein concentration at half maximum DNA binding. The values shown are derived from five independent experiments.

bThe specificity is the ratio of non-specific to specific binding (42):

Specificity = Keq(app)non-specific DNA/Keq(app)specific A:T spacer.

We next compared the non-specific DNA binding activity of these proteins. For these experiments, we made use of a 195 bp DNA fragment that does not carry a specific E2 binding site. When the 6 E2 DBD binds to this DNA fragment it does not form a defined retarded complex but rather it produces a retarded smear (Figure 5A, lanes 2–5). This smearing is due to the dissociation of weak, non-specific complexes during electrophoresis (31,32). E2ΔLL also binds to this non-specific DNA to form a retarded smear (Figure 5A, lanes 6–9). However, faint discrete retarded bands are formed at lower E2ΔLL concentrations, suggestive of more tightly bound complexes (lanes 6 and 7) and lower protein concentrations are required to shift all of the labelled DNA. To compare the non-specific DNA binding activity of these proteins in more detail we performed several repeats, quantified the amount of free and bound DNA as described above and determined the apparent equilibrium constant (Figure 5B and Table 1). The non-specific DNA binding activity of E2ΔLL is around 10-fold higher that of the wild-type protein (Table 1). The same results were obtained using a second, unrelated non-specific oligonucleotide (data not shown).

Figure 5.

Non-specific DNA binding activity of the 6 E2 and E2ΔLL proteins. (A) A representative gel retardation experiment showing the binding of 6 E2 and E2ΔLL to labelled 195 bp non-specific DNA sequence. Lane 1 contains no protein, lanes 2–5 contain 0.25, 0.5, 0.75 and 1.0 µM E2 and lanes 6–9 contain 0.25, 0.5, 0.75 and 1.0 µM E2ΔLL. Free and bound DNA were separated and visualized as described in Figure 4. (B) A graph showing the binding of E2 and E2ΔLL to the labelled non-specific DNA from (A). The amount of free and bound DNA was determined using a PhosphorImager and the percentage of labelled DNA bound {[bound labelled DNA/(bound labelled DNA + free labelled DNA)] × 100} is plotted against the amount of protein added.

Taken together with the results of the specific DNA binding assays (Figure 4) these results clearly show that E2ΔLL has increased DNA binding activity. However, whereas specific binding has increased around 2-fold, binding to non-specific DNA has increased around 10-fold, indicating that the overall DNA binding specificity has decreased (Table 1) albeit without appearing to alter the preference for an A:T spacer sequence. This is clearly apparent from the 6-fold drop in ratio of the dissociation constants for non-specific and specific DNA given in Table 1. This is consistent with previous data which has shown that ‘single chain’ HPV 16 E2 DBD proteins with increased protein stability have increased DNA binding specificity (33).

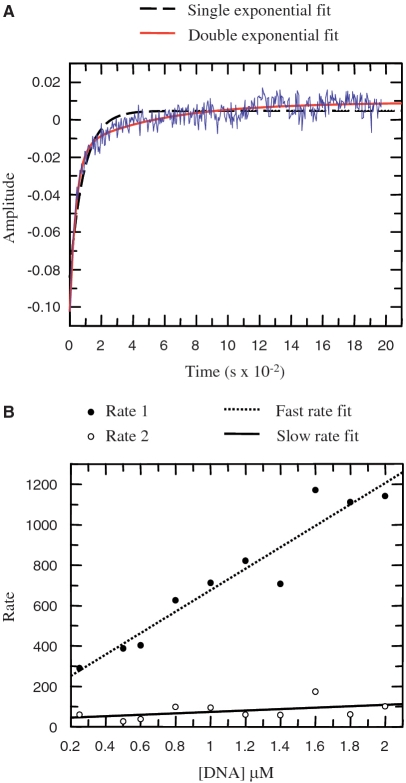

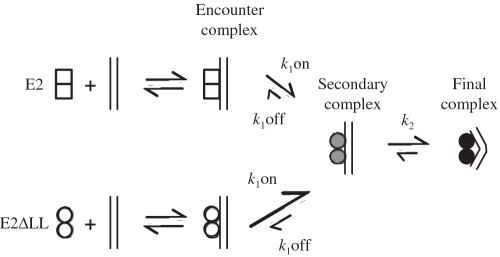

Structural rearrangements on DNA binding

We have previously described an analysis of the structural rearrangements in the 6 E2 DBD that accompany DNA binding in solution (13). As in the case of the HPV 16 E2 DBD (34), the change in fluorescence of protein tryptophan residues associated with complex formation indicates that DNA binding occurs in two distinct phases: a faster interaction presumed to be non-specific and diffusion-limited and a slower interaction that is thought to be a result of protein rearrangements during formation of the specific complex (34,35). In order to compare the DNA binding kinetics of 6 E2 and E2ΔLL we analysed intrinsic fluorescence during complex formation with an E2 site containing an A:T rich spacer exactly as described previously (13). Representative data are shown in Figure 6 and the rate constants derived from the data are shown in Table 2. Both proteins show an increase in the amplitude of fluorescence with increasing A:T spacer DNA concentration. The association data were fitted to a double exponential curve to derive the fast and slow rates in each case and the rates were plotted against DNA concentration. Similar to the previous results with wild-type HPV 16 E2, the fast rate for E2ΔLL binding increases with DNA concentration, while the slow rate remain relatively constant as DNA concentration is increased (Figure 6B). The slow rates for 6 E2 and E2ΔLL are very similar, suggesting that in each case the rearrangements occurring during formation of the tight-binding complex are not significantly different (Table 2). However, the initial fast rate for the association of E2ΔLL is increased by around 10-fold compared to the wild-type protein. The off-rate is also increased, but only around 2-fold. Together these differences indicate about a 5-fold increase in binding to DNA. The differences in initial binding to the A:T spacer DNA are very unlikely to be due to differences in the electrostatic surfaces of the two proteins since these are unchanged by the mutation. These data therefore suggest that the so-called initial complex formed by the wild-type protein is not a diffusion-limited encounter complex rather it is a secondary complex that forms after the encounter complex (as indicated in the model shown in Figure 7, E2). Increasing the flexibility of the E2 DBD appears to facilitate formation of this secondary complex and we presume that it then becomes diffusion-limited (Figure 7, E2ΔLL). Increased flexibility has little or no effect on the structural rearrangements that follow and are required in order to form the final complex. Pre-bent DNA might facilitate formation of the initial complexes although it would seem more likely that it facilitates the protein structural rearrangements that produce the final complex. However, it is important to note that clarification of this point would require kinetic data with the G:C spacer DNA and we were unable to obtain this information due to the weakness of the interaction of both proteins with this DNA. In sum our data are not inconsistent with a model for DNA binding proposed by Ferreiro and de Prat-Gay (34) in which the E2 DBD is proposed to exist in two populations which bind DNA through different pathways. In one state, E2 binds preferentially to pre-bent DNA and then undergoes structural rearrangements resulting in tight binding. However, another population of E2 proteins bind to both pre-bent and non-bent DNA to form directly the final complex. The increased binding affinity correlated with increased DBD flexibility could arise from a greater proportion of the protein being present in the second population.

Figure 6.

Kinetic association data. (A) Typical stopped-flow fluorescence data for 2 µM E2 DBD and 0.25 µM A:T rich site. A minimum of 10 curves were averaged to minimize noise. The raw data (displayed in blue) was fitted to either a double exponential curve (red line) or to a single exponential curve (dashed line). The double exponential curve correlates well with the data. (B) The rates obtained from the double exponential curves fitted to the raw data as shown above were plotted against the DNA concentration. A straight line could be fitted to the fast rate (dotted line) and slow rate (solid line).

Table 2.

Kinetic data for E2- and E2ΔLL–DNA complex formation obtained using stopped-flow fluorescence experiments

| Fast rate | Slow rate | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| k1 on (M−1 s−1) | k1 off (s−1) | k2 (s−1) | |

| HPV 6 E2 | (9.2 ± 0.8) × 107 | 68 ± 16 | 29 ± 6 |

| HPV 6 E2ΔLL | (1.0 ± 0.1) × 109 | 182 ± 33 | 44 ± 18 |

Figure 7.

A model for the E2-DNA complex formation. A schematic representation of the binding of 6 E2 and E2ΔLL to DNA. E2 dimers (open squares) bind to DNA to form a diffusion limited encounter complex. This subsequently forms a secondary complex (shaded circles) which in turn undergoes further structural rearrangement to form the final tightly bound complex (filled circles). We propose that the increased protein flexibility shown by E2ΔLL (open circles) facilitates formation of the secondary complex but has little or no effect on the following step. Formation of the secondary complex for E2ΔLL is then diffusion limited.

CONCLUSIONS

Many protein–DNA complexes contain bent or otherwise deformed DNA and the importance of DNA flexibility in DNA recognition has long been recognized and studied intensively (10,13,36–38). Similarly, although less well-studied, protein adaptability can also generate or favour the formation of specific interactions and thereby increase binding (39,40). In contrast, reduced protein movement in the complex would be expected to diminish this fine-tuning of complementarity, and impart an entropic cost to the interaction thereby weakening binding. Here we have shown that the HPV 6 E2 DBD has very low intrinsic flexibility in solution. We have also shown that by altering the overall and inter-domain protein flexibility of the HPV 6 E2 DBD, unusually via partial disruption of the hydrophobic core of the protein, both non-specific and specific DNA binding can be improved. In this instance increased protein adaptability appears to dominate binding, overcoming the expected entropic cost normally associated with freezing a more mobile protein in a bound complex. These surprising results suggest that engineering of domain associations in 2-fold symmetric dimers—commonly found in DNA binding proteins—may provide an elegant route to increased binding. Changes that shift the dimeric E2 binding surface towards the conformation observed in its DNA complexes would generally be expected to be favourable for binding. Improved protein adaptability has a greater effect on non-specific DNA binding, suggesting that it could mimic protein conformation changes that occur during non-specific interactions.

We also note that increasing the adaptability of the HPV 6 E2 DBD does not appear to alter its capacity for indirect readout. These data suggest that in this case limited protein flexibility is not responsible for indirect readout of DNA conformation. Presumably the entropic cost associated with restricting E2 to a conformation best suited to DNA binding is not significant compared to the overall energy change brought about by specific binding. In support of this conclusion, our stopped-flow kinetic studies show that increased protein flexibility has little or no effect on the structural rearrangements that follow initial binding. However, increased protein flexibility has a major effect on DNA binding specificity, significantly decreasing the preference for specific DNA over non-specific DNA. This result is not inconsistent with converse findings by Prat-Gay and co-workers who have previously shown that ‘single chain’ HPV 16 E2 DBD proteins with increased protein stability have decreased non-specific DNA binding and increased specific binding (33). The effect of the linker chain on protein adaptability in this engineered form of E2 is not clear, but might be expected to limit conformational changes. The restricted adaptability of the HPV 6 E2 DBD is, therefore, likely to be of primary importance for the ability of this protein to locate its specific target sites in the viral genome in the presence of a vast excess of host genomic DNA.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

FUNDING

Wellcome Trust project grant (077355); Wellcome Trust equipment grant for the 600 MHz cryo-probe (082352); Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council project (grant BBF014570); University of Bristol Postgraduate Research Scholarship (to V.F.). El Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología PhD studentship (to K.C.L.); Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council and Varian CASE PhD studentship (to M.S.). Funding for open access charge: The Wellcome Trust.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors are very grateful to Prof. Tony Clarke (University of Bristol), Dr Gonzalo de Prat Gay (Fundación Instituto Leloir) and Dr Ignacio E. Sanchez (CONICET and University of Buenos Aires) for useful discussions and comments on the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.de Prat Gay G, Gaston K, Cicero DO. The papillomavirus E2 DNA binding domain. Frontiers Biosci. 2008;13:6006–6021. doi: 10.2741/3132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hegde RS. The papillomavirus E2 proteins: structure, function, and biology. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 2002;31:343–360. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.31.100901.142129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Giri I, Yaniv M. Structural and mutational analysis of E2 trans-activating proteins of papillomaviruses reveals three distinct functional domains. EMBO J. 1988;7:2823–2829. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb03138.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McBride AA, Byrne JC, Howley PM. E2 polypeptides encoded by bovine papillomavirus type 1 form dimers through the common carboxyl-terminal domain: transactivation is mediated by the conserved amino-terminal domain. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1989;86:510–514. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.2.510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thain A, Webster K, Emery D, Clarke AR, Gaston K. DNA binding and bending by the human papillomavirus type 16 E2 protein. Recognition of an extended binding site. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:8236–8242. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.13.8236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sanchez IE, Dellarole M, Gaston K, de Prat Gay G. Comprehensive comparison of the interaction of the E2 master regulator with its cognate target DNA sites in 73 human papillomavirus types by sequence statistics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:756–769. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm1104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hegde RS, Grossman SR, Laimins LA, Sigler PB. Crystal structure at 1.7 A of the bovine papillomavirus-1 E2 DNA-binding domain bound to its DNA target. Nature. 1992;359:505–512. doi: 10.1038/359505a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hines CS, Meghoo C, Shetty S, Biburger M, Brenowitz M, Hegde RS. DNA structure and flexibility in the sequence-specific binding of papillomavirus E2 proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 1998;276:809–818. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferreiro DU, Dellarole M, Nadra AD, de Prat Gay G. Free energy contributions to direct readout of a DNA sequence. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:32480–32484. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505706200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dell G, Wilkinson KW, Tranter R, Parish J, Brady RL, Gaston K. Comparison of the structure and DNA-binding properties of the E2 proteins from an oncogenic and a non-oncogenic human papillomavirus. J. Mol. Biol. 2003;334:979–991. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang YL, Xi ZQ, Hegde RS, Shakked Z, Crothers DM. Predicting indirect readout effects in protein–DNA interactions. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:8337–8341. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402319101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zimmerman JM, Maher LJ. Solution measurement of DNA curvature in papillomavirus E2 binding sites. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:5134–5139. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hooley E, Fairweather V, Clarke AR, Gaston K, Brady RL. The recognition of local DNA conformation by the Human Papillomavirus type 6 E2 protein. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:3897–3908. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hegde RS, Wang AF, Kim SS, Schapira M. Subunit rearrangement accompanies sequence-specific DNA binding by the bovine papillomavirus-1 E2 protein. J. Mol. Biol. 1998;276:797–808. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eliseo T, Sanchez IE, Nadra AD, Dellarole M, Paci M, de Prat Gay G, Cicero DO. Indirect DNA readout on the protein side: coupling between histidine protonation, global structural cooperativity, dynamics, and DNA binding of the human papillomavirus type 16 E2C domain. J. Mol. Biol. 2009;388:327–344. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Veeraraghavan S, Mello CC, Androphy EJ, Baleja JD. Structural correlates for enhanced stability in the E2 DNA-binding domain from bovine papillomavirus. Biochemistry. 1999;38:16115–16124. doi: 10.1021/bi991633x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cicero DO, Nadra AD, Eliseo T, Dellarole M, Paci M, de Prat Gay G. Structural and thermodynamic basis for the enhanced transcriptional control by the human papillomavirus strain-16 E2 protein. Biochemistry. 2006;45:6551–6560. doi: 10.1021/bi060123h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hegde RS, Androphy EJ. Crystal structure of the E2 DNA-binding domain from human papillomavirus type 16: implications for its DNA binding-site selection mechanism. J. Mol. Biol. 1998;284:1479–1489. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Falconi M, Santolamazza A, Eliseo T, de Prat Gay G, Cicero DO, Desideri A. Molecular dynamics of the DNA-binding domain of the papillomavirus E2 transcriptional regulator uncover differential properties for DNA target accommodation. FEBS J. 2007;274:2385–2395. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.05773.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Falconi M, Oteri F, Eliseo T, Cicero DO, Desideri A. MD simulations of papillomavirus DNA-E2 protein complexes hints at a protein structural code for DNA deformation. Biophys. J. 2008;95:1108–1117. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.130849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pellecchia M, Sebbel P, Hermanns U, Wuthrich K, Glockshuber R. Pilus chaperone FimC-adhesin FimH interactions mapped by TROSY-NMR. Nat. Struct. Biol. 1999;6:336–339. doi: 10.1038/7573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Farrow NA, Zhang O, Forman-Kay JD, Kay LE. A heteronuclear correlation experiment for simultaneous determination of 15N longitudinal decay and chemical exchange rates of systems in slow equilibrium. J. Biomol. NMR. 1994;4:727–734. doi: 10.1007/BF00404280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lipari G, Szabo A. Model-free approach to the interpretation of nuclear magnetic-resonance relaxation in macromolecules. 1. Theory and range of validity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1982;104:4546–4559. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lipari G, Szabo A. Model-free approach to the interpretation of nuclear magnetic-resonance relaxation in macromolecules. 2. Analysis of experimental results. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1982;104:4559–4570. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Clore GM, Szabo A, Bax A, Kay LE, Driscoll PC, Gronenborn AM. Deviations from the simple two-parameter model-free approach to the interpretation of nitrogen-15 nuclear magnetic relaxation of proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990;112:4989–4991. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mandel AM, Akke M, Palmer AG., III Backbone dynamics of Escherichia coli ribonuclease HI: correlations with structure and function in an active enzyme. J. Mol. Biol. 1995;246:144–163. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.0073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vranken WF, Boucher W, Stevens TJ, Fogh RH, Pajon A, Llinas M, Ulrich EL, Markley JL, Ionides J, Laue ED. The CCPN data model for NMR spectroscopy: development of a software pipeline. Proteins. 2005;59:687–696. doi: 10.1002/prot.20449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liang H, Petros AM, Meadows RP, Yoon HS, Egan DA, Walter K, Holzman TF, Robins T, Fesik SW. Solution structure of the DNA-binding domain of a human papillomavirus E2 protein: evidence for flexible DNA-binding regions. Biochemistry. 1996;35:2095–2103. doi: 10.1021/bi951932w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nadra AD, Eliseo T, Mok YK, Almeida CL, Bycroft M, Paci M, de Prat Gay G, Cicero DO. Solution structure of the HPV-16 E2 DNA binding domain, a transcriptional regulator with a dimeric beta-barrel fold. J. Biomol. NMR. 2004;30:211–214. doi: 10.1023/b:jnmr.0000048942.96866.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Clore GM, Driscoll PC, Wingfield PT, Gronenborn AM. Analysis of the backbone dynamics of interleukin-1 beta using two-dimensional inverse detected heteronuclear 15N-1H NMR spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 1990;29:7387–7401. doi: 10.1021/bi00484a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gaston K, Fried M. CpG methylation has differential effects on the binding of YY1 and ETS proteins to the bi-directional promoter of the Surf-1 and Surf-2 genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:901–909. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.6.901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kolb A, Spassky A, Chapon C, Blazy B, Buc H. On the different binding affinities of CRP at the lac, gal and malT promoter regions. Nucleic Acids Res. 1983;11:7833–7852. doi: 10.1093/nar/11.22.7833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dellarole M, Sanchez IE, Freire E, Prat-Gay G. Increased stability and DNA site discrimination of "single chain" variants of the dimeric beta-barrel DNA binding domain of the human papillomavirus E2 transcriptional regulator. Biochemistry. 2007;46:12441–12450. doi: 10.1021/bi701104q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ferreiro DU, de Prat Gay G. A protein-DNA binding mechanism proceeds through multi-state or two-state parallel pathways. J. Mol. Biol. 2003;331:89–99. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00720-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ferreiro DU, Sanchez IE, de Prat Gay G. Transition state for protein–DNA recognition. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:10797–10802. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802383105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gartenberg MR, Crothers DM. DNA sequence determinants of CAP-induced bending and protein binding affinity. Nature. 1988;333:824–829. doi: 10.1038/333824a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gaston K, Kolb A, Busby S. Binding of the Escherichia coli cyclic AMP receptor protein to DNA fragments containing consensus nucleotide sequences. Biochem. J. 1989;261:649–653. doi: 10.1042/bj2610649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Koudelka GB. Recognition of DNA structure by 434 repressor. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:669–675. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.2.669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kalodimos CG, Biris N, Bonvin AMJJ, Levandoski MM, Guennuegues M, Boelens R, Kaptein R. Structure and flexibility adaptation in nonspecific and specific protein-DNA complexes. Science. 2004;305:386–389. doi: 10.1126/science.1097064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tzeng SR, Kalodimos CG. Dynamic activation of an allosteric regulatory protein. Nature. 2009;462:368–372. doi: 10.1038/nature08560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.DeLano WL. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System. CA, USA: DeLano Scientific Palo Alto; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ferreiro DU, Lima LM, Nadra AD, Alonso LG, Goldbaum FA, de Prat Gay G. Distinctive cognate sequence discrimination, bound DNA conformation, and binding modes in the E2 C-terminal domains from prototype human and bovine papillomaviruses. Biochemistry. 2000;39:14692–14701. doi: 10.1021/bi001694r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.