Abstract

Culture provides the context for all health care and social service throughout the human lifespan. Improving end-of-life and palliative care and enhancing patient and family outcomes requires nuanced understanding of cultural contexts for those who provide care and those who receive it. This article proposes an emerging model of culturally-congruent care that can guide intervention for social workers, mental health professionals, nurses, and other health care workers caring for a diverse population of patients, families, and communities.

Keywords: Cultural Competence, diversity, cultural congruence, health disparity

Culture provides the context for all health and social services throughout the human lifespan across conditions, settings, and situations. Culture is the mechanism through which people learn how to be in the world, how to behave, what to value, and what gives meaning to existence. Culture underlies health care delivery at client, provider, and system levels because it is the foundation for expectations, actions, interactions, and meanings of care. As patients, families, and communities grapple with the realities of human mortality, issues of culture come into focus in ways that heighten the relevance of cultural concerns at this time in life. As social workers and other health care providers interact with people dealing with life-limiting conditions, issues of culture and care across cultural boundaries become critically important. Improving end-of-life and palliative care and enhancing patient and family outcomes requires nuanced understanding of cultural contexts for those who provide care and those who receive it. The purpose of this paper is to describe an emerging model of culturally-congruent care and discuss ways in which it can guide intervention for social workers, mental health professionals, nurses, and other health care workers caring for diverse patients, families, and communities.

Culture and End-of-Life

Suboptimal palliative and end-of-life (EOL) care for dying people and inadequate support for families and communities remain major concerns in spite of the growth of hospice and palliative care services across the U.S. In the 2004 National Institutes of Health State of the Science Conference Report it is noted that theoretical and empirical bases remain insufficient for many common palliative and end-of-life interventions (2004). Many people, including those in racial/ethnic and cultural minority groups, remain at-risk for poor-quality EOL care. Inequities in access to and use of available EOL services constitute major public health and social justice problems. The National Institute of Nursing Research cites the elimination of health disparities as a top area of research emphasis along with enhancing quality of life at end of life among diverse groups (2006). The need for understanding and adapting care across a variety of cultural contexts is nowhere more evident than in the area of hospice and palliative care at end of life.

Culture is a construct that is still being defined and debated in the literature of many academic and professional disciplines. There is emerging consensus, however, that culture has three main characteristics: 1) culture emerges in interactions between humans and environments, 2) culture consists of shared elements, and 3) culture is transmitted across time periods and generations (Triandis, 2007). There are also many current calls for expansion of our thinking about cultural variables to include more than just race and ethnicity (Cohen, 2009). In the proposed model, culture is broadly defined as a “socially-transmitted and socially-constructed constellation consisting of such things as practices, competencies, ideas, schemas, symbols, values, norms, institutions, goals, constitutive rules, artifacts, and modifications of the physical environment” (Fiske, 2002, p.85). Cultural variables form a background to human interaction across all areas of health and illness care and come to the foreground when people face the realities of imminent mortality. Issues of tradition, ritual, family relationships, and the meaning of life and death become exquisitely relevant at end of life as patients, family caregivers, and clinicians negotiate care towards dignified dying (Coenen, Doorenbos, & Wilson, 2007).

Although death is a universal human experience, there is ample evidence that in the context of the western biomedicine, the dying process is often accompanied by excess pain and suffering (Cintron & Morrison, 2006; Doorenbos, Given, Given, & Verbitsky, 2006); caregiver burden (Doorenbos, et al., 2007); and a lack of effective communication between professionals, lay caregivers, and terminally-ill patients (Fried, Bradley, & O'Leary, 2003). Hospice programs across the nation have responded to many of these concerns and have pointed the way towards better care of dying patients and their families. In hospice the goal is “dignified dying” in which care is guided by patient and family values; dignity is maintained; pain and suffering are relieved; and dying is experienced as a growth process that is a normal part of human life (Coenen, et al., 2007; Egan & Labyak, 2001). Hospice programs focus on interdisciplinary collaboration to provide comfort for the patient and family within their unique cultural contexts. However, even within hospice programs, there continue to be problems with providing care in ways that respect cultural diversity and maximize availability, accessibility, and acceptability of services (AHRQ, 2009). Additionally, many people facing chronic, debilitating, life-threatening conditions do not enroll in hospice programs. According to the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization, 82% of hospice patients are White, 7.5% Black, and the rest from other backgrounds (2005). The data suggest that Whites (about 75% of the U.S. population) are overrepresented and Blacks (±12%) and persons from other groups (±13%) underrepresented among hospice patients (Census, 2005).

Cultural Competence

A great deal of recent interest has centered on enhancing cultural competence among healthcare providers as a means of eliminating some of the chronic disparities that mark the American healthcare system (Fortier & Bishop, 2004; National Association of Social Workers, 2007; National Center for Cultural Competence, 2009) and improving EOL care. Clinicians are people engaged in healthcare services who focus on direct client care from within one of the professional disciplines such as social work, nursing, or medicine. Providers include all members of the interdisciplinary healthcare team including clinicians, administrators, clerical and support personnel. Most prior research has focused on the professional clinician side of healthcare by seeking better ways to define, measure, and improve clinician knowledge and/or performance in response to expanding cultural challenges. Definitions of cultural competence vary (e.g. Campinha-Bacote, 1999; Giger & Davidhizar, 2004; Purnell, 2002). In the proposed model cultural competence is considered a developmental process characteristic of a person rather than an attribute of an agency, population, program, or object. Previous cultural competence measurements have mostly focused exclusively on clinicians and often include discipline-, setting-, or population-specific tests of knowledge or assumptions that limit their usefulness (Kumas-Tan, Beagan, Loppie, MacLeod, & Frank, 2007). Efforts to improve clinician cultural competence and to better prepare students to enter the health and social service fields as clinically-competent professionals have dominated the discussion. Most educational efforts have focused on physicians (Griswold, 2006; Haidet, 2006) and nurses (Anderson, Ruiz, & Fongwa, 2007; Brown, 2008; Leiper, Van Horn, & Upadhyaya, 2008) with the rationale that these two disciplines represent the majority of clinicians and therefore should have the greatest potential impact on client outcomes. The disciplines of social work and mental health have largely been omitted from this discussion as have the growing spectrum of ancillary staff involved in providing patient care. What has also been lacking is a clear association of cultural competence with client outcomes (Fortier & Bishop, 2004). Although clinician and provider cultural competence is widely mandated and intuitively attractive, much of the work so far has been based on observation, case study, and anecdotes. Sufficient evidence has not yet been presented to support the commonly-held belief that cultural competence is sufficient to produce desired patient and family outcomes. In EOL care, positive patient and family health outcomes are defined as a dignified dying for the patient (Coenen, et al., 2007) and sufficient support for family caregivers to prevent or decrease negative health effects of caregiving (Mystakidou, Tsilika, Parpa, Galanos, & Vlahos, 2007).

Culturally-congruent Care

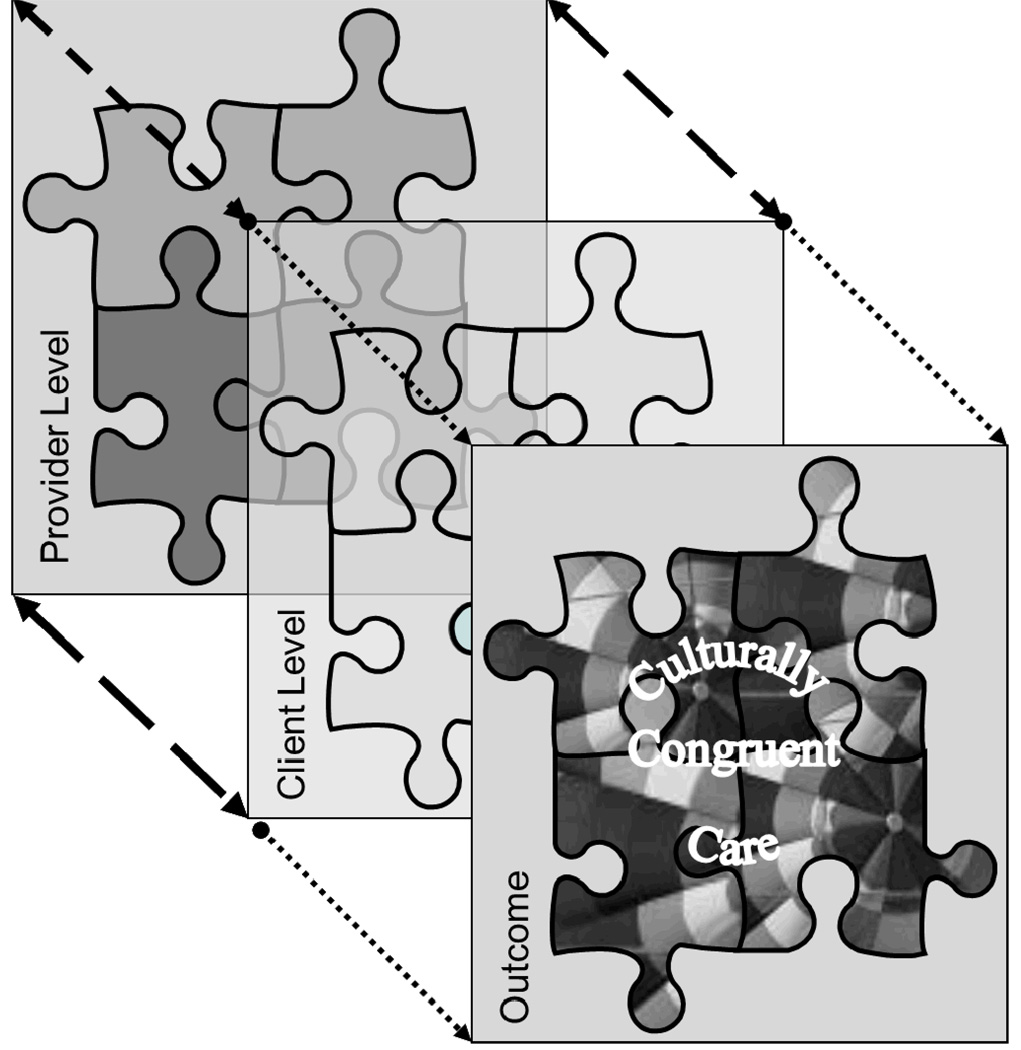

In part, the difficulty in linking cultural competence to patient and family outcomes derives from failure to consider the cultural domains that patients bring to healthcare encounters. The authors have articulated a conceptual model, derived from synthesis of extant theoretical work in transcultural healthcare, to guide research, education, and practice (Schim, Doorenbos, Benkert, & Miller, 2007). Whereas this earlier conceptual work emphasized the provider cultural competence level of the model, the present work adds more detailed discussion of the client level dynamics, some of the societal cultural confounders, and ramifications for culturally-congruent clinical practice. The model describes both provider and client-level elements that must be considered in order to begin to capture the complexities of culturally-congruent health care. Cultural congruence is a process of effective interaction between the provider and client levels. The model is based on the idea that cultural competence is ever-evolving; providers must continue to improve their quality of communication, leading to improved quality of care. However, care offered is not always equal to care received. Patients and families bring their own values, perceptions, and expectations to health care encounters which also influence the creation or destruction of cultural congruence.

Our revised model (shown in Figure 1) describes key constructs as a 3-dimensional jigsaw puzzle, with one layer showing provider elements, another layer with client elements, and the culturally-congruent care that occurs when provider and patient layers fit together effectively. The terms and constructs defined in discussing this model are those of the authors unless a source is otherwise noted.

Figure 1.

3-D Model of Culturally-congruent Care

Provider Level of Model

The provider level of the puzzle has 4 components: (a) cultural diversity, (b) cultural awareness, (c) cultural sensitivity, and (d) cultural competence behaviors. This level of the model has been more fully articulated elsewhere (Schim, et al., 2007) and has been used as the basis for a Cultural Competence Assessment tool for use with diverse healthcare providers and professional students (Doorenbos & Schim, 2004; Doorenbos, Schim, Benkert, & Borse, 2005; Schim, Doorenbos, & Borse, 2005, 2006; Schim, Doorenbos, Miller, & Benkert, 2003)

Cultural diversity is a reality in today’s healthcare and social environments. Although much of the extant work on cultural diversity has focused on issues of race, ethnicity, language, and religious difference, we endorse a much broader diversity perspective that includes many dimensions of both difference and similarity between groups and within groups. Issues of age, gender, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, and education also must be considered when working with concepts of culture. Individual backgrounds, experiences, and exposures to diverse human cultural patterns vary widely from place-to-place and change over time based on the number and type of people encountered and the nature and intensity of cross-cultural interactions.

Cultural awareness is a cognitive construct. Regardless of the facts of an individual’s diversity environment, knowledge and thought are necessary to appreciate the ways in which cultures vary and are similar, the ways that cultural contexts influence personal meaning, and the profound effects that culture has on healthcare from both provider and recipient perspectives.

Cultural sensitivity is an affective or attitudinal construct. Each clinician’s attitudes about themselves and others and their openness to learning about cultural dimensions and diversity are essential to cultural sensitivity. Openness to self-exploration of personal cultural heritage and experiences, the disciplinary heritage into which clinicians are socialized, and the organizational cultures within which services are provided is essential to cultural sensitivity.

Cultural competence is a behavioral construct consisting of actions in response to the demands of cultural diversity, awareness, and sensitivity. It is demonstration of behaviors in practice that help to bridge the differences and barriers that often occur when people of diverse cultures interact and communicate. The process of developing cultural competence is dynamic over time in response to changing diversity environments and experiences, acquisition of new awareness (knowledge and insights) and skills, and growing sensitivity to self and others.

Client Level of Model

The client level of the model consists of those patient, family, and community attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors that represent areas of greatest similarity and difference both between and within cultural groups, subgroups, and individuals. The term client refers to individuals, families or other groups, or whole communities that are the objects of practice in the health disciplines in various clinical settings. In palliative and EOL practice the most-frequent clients are individual patients and their families. Although patients and families certainly could also be described in terms of their personal cultural diversity, awareness, sensitivity, and competence, we chose to reserve those construct labels for the provider level in order to be consistent with the usage common among current authors in the field. We added the client level of the model to particularly highlight some of the cultural dimensions that lend themselves best to assessment and interventions that can lead to more effective cross-cultural care. Much of our thinking about the client level of our model is derived from the landmark theoretical work of Madeleine Leininger (1991; Leininger & McFarland, 2002). Although variation within cultures can be great as or greater than the variations between cultures, there are central features that are relevant to both global and individual cultural contexts. Understanding ways in which groups tend to differ on these dimensions of culture allows for ways to “think globally” about diversity. Recognizing that individuals within any one group also may differ on these dimensions allows for providers to “act locally” in tailoring assessment and intervention to specific client needs and wants and guards against inappropriate stereotyping. A list of common and unique cultural aspects is presented in Table1. This list is in no way intended to be exhaustive, but rather to serve as a starting point for critical thinking about what patients and families bring with them to each health care and social service interaction. Which aspects at the client level are particularly salient to healthcare in general and palliative and end-of-life care specifically may vary depending on the nature of the community of service at any given point in time.

Table 1.

Common and unique aspects of client culture

| Common Cultural Constructs | Unique Individual and Group Variations |

|---|---|

| family | Who is included. What relatives are called, Role of family in individual life. Family structure variations. |

| home | What home means. Where located and how configured. |

| health, illness, caring | Different meanings of terms. Different expressions of care. Care sources (e.g. lay healers), expectations of caregivers |

| nutrition / food patterns | Prescribed / Prohibited foods, “good” food, home cooking |

| spirituality | Religious rituals, spiritual practices, meaningful artifacts (things) |

| education | Who gets what type of education, value placed on education, perception of professional vs. lay roles in healthcare |

| decision making | How decisions are made and by whom. Individual autonomy vs. collectivism. |

| values, beliefs, customs | Personal and familial values, beliefs, customs |

| time orientation | Meaning of time, schedules, and calendars. Interpretations of promptness and lateness. |

| personal space | Comfortable conversational distance. Power relationships |

| communication | Primary language, literacy, language facility, Verbal vs. non-verbal, meaning of gestures |

Putting the Provider and Client Levels Together

Culturally-congruent care can occur when the provider and client levels fit well together. It is the process through which providers and clients create an appropriate fit between professional practice and what patients and families need and want in the context of relevant cultural domains. Through culturally-congruent care patient and family desires and needs are skillfully addressed in interaction with providers who adapt care to meet the patients and families’ unique needs. The construct of culturally-congruent care moves the field forward by recognizing that it is in a dynamic interaction between clients and providers that care occurs and that both client patient, family and provider attitudes, perceptions, and behaviors influence outcomes.

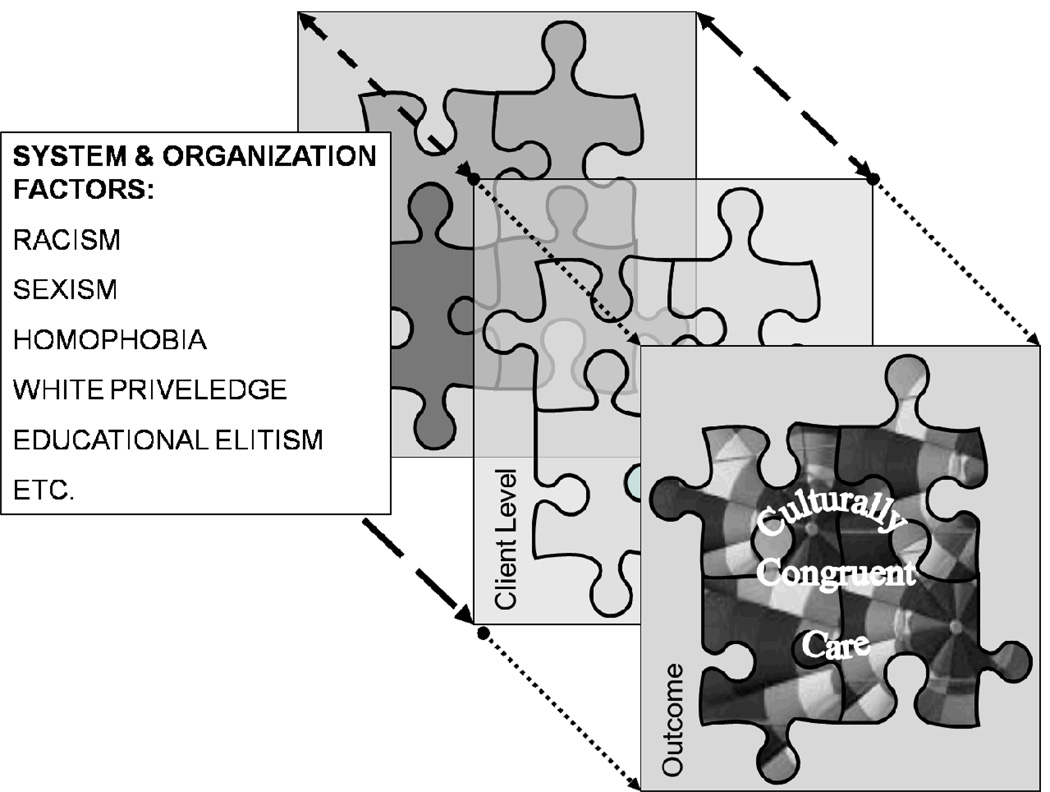

Cultural Confounders

In developing the 3-D Puzzle Model and sharing ideas with a variety of students and colleagues it became apparent that there is an often-overlooked layer of issues that gets in the way of providers and clients coming together to create culturally-congruent care. Some such issues are the persistent societal oppressions of racism, sexism, classism, homophobia, and unacknowledged privilege (Burkard & Knox, 2004; Giddings, 2005; Neville, Spanierman, & Doan, 2006; Puzan, 2003). Critical theorists have raised objections to recent work on cultural competence and cultural congruence as having an emphasis on individual identity instead of addressing unequal power relationships and systemic oppressions (Gray & Thomas, 2006; Gustafson, 2005). Some argue that a depoliticized approach relies on individual change to ensure cultural competence while ignoring the deeply-ingrained systemic problems of racism and other “isms” (Allen, 2006). Cross-cultural encounters in healthcare and social service present a challenge to entrenched privileges which are those advantages that accrue to professionals by virtue of their education, income, gender, race/ethnicity, history, or societal mandates (Abrums, 2004; Abrums & Leppa, 2001). Acknowledging the profound and pervasive effects of the societal issues that get in the way of culturally-congruent care and consciously working toward the mitigation of these effects is essential to ultimately solving the macro-level problems of health disparities, equal access, and social justice (Schim, Benkert, Bell, Walker, & Danford, 2007).

Institutional and organizational barriers can also impede the process of effective culturally-congruent care. Many recent mandates for health care organizations such as the Joint Commission standards (2008, April) and CLAS rules (Office of Minority Health, 2009) are aimed at making institutions more culturally competent. In our proposed model, cultural competence is defined as a personal attribute rather than a characteristic of an organization. People are more or less competent; organizations provide culturally-appropriate services in culturally-acceptable ways and hire, develop, and support culturally-competent employees. In our emerging model, the organizational elements are part of the “stuff” that comes between the providers and the clients to either facilitate or block culturally-congruent care. An example of an organizational attribute that facilitates culturally-congruent care would be found in a hospital that has for many years served a low socioeconomic urban community and has developed a reputation in that community for fair and non-judgmental treatment for people of color regardless of ability to pay. An example of an organizational attribute that inhibits culturally-congruent care would be a hospice agency in a community with a large American Arab population that does not offer signage, forms, or educational material in Arabic. Organizational assessment, the recognition of overt and covert barriers to care, and active participation in changing organizational cultural towards more culturally-appropriate responses to specific community-of-service needs are behaviors that are consistent with individual provider cultural competence.

Approach to Intervention

Based on our 3-D Puzzle Model a four-step approach to intervention is recommended. The four steps are labeled as Appreciation, Accommodation, Negotiation, and Explanation and each approach will be briefly described here with a few examples.

Appreciation

The first stage, and the one most closely connected with assessment, is appreciation. In this most-often-used step, the provider observes and learns about the client’s cultural contexts and personal beliefs, values, and patterns. The provider then thinks about their global understandings of culture and works with the client to put observed behaviors into perspective. The common assessment question that leads to this first step is, “Tell me more about…” Then listening carefully to the client’s response, the provider decides whether or not any intervention is really necessary. It is one of the challenges of the health and social service professions to recognize that just because we know how to intervene does not mean that it is appropriate to do so in all cases. Clients have different values, beliefs, rituals, and customs than their providers but “different” should not imply “wrong.”

An example of cultural appreciation has been observed as a large, multigenerational, extended family gathers at the bedside of an actively dying patient. The room is small, the day warm, and the new social worker unaccustomed to such apparent chaos and confusion. Although the social worker herself is from a small Midwestern family, she takes the time to observe and learn from her assessment about the definition of family and the meaning of having family present at this time of transition. She learns that “family” for this patient includes aunts, uncles, and cousins as well as parents, siblings, and children. Family also includes members of the faith community and close neighbors. In their cultural context, the presence of the whole extended family at the bedside is the appropriate expression of their love and caring. After learning about how the family understands their need for having family present, the social worker decides appropriately that the desired family pattern does not require intervention at all, but rather can be appreciated and left alone. If the things that the client and family want do not cause active harm, additional discomfort, or undue annoyance of other people, then simple accepting and appreciating the differences and similarities of behavior and leaving things alone is the most respectful approach.

Accommodation

The next step of intervention involves accommodation. As the provider observes and explores the cultural beliefs, values, and desired behaviors of the client, there are often aspects of care that need to be actively changed to accomplish cultural congruence. Fortunately, many of the accommodations that are necessary are relatively simple to perform.

An example would be the dying patient who is Muslim and whose family request that he be facing Mecca in the last hours. Moving the bed to the appropriate direction is an accommodation that takes a bit of time and planning, but that is usually greatly appreciated and accomplished without major effort. Accommodation requires out-of-the-box thinking about how care can be adapted to meet client needs and wants. The Western bio-medical institutional culture often values rules, consistency, and treating everyone the same. Cultural accommodation requires flexibility and treating people the way they want to be treated whenever it is at all possible.

Negotiation

The third step of intervention is negotiation. Sometimes simple accommodation is not feasible due to individual, organizational, scientific, or other seemingly immovable barriers. Effective cultural negotiation requires careful assessment as do appreciation and accommodation and often is a chance for the demonstration of creativity. The provider engaging in negotiation needs to understand the meaning of the culturally desired behaviors and look for ways to implement as much accommodation as possible under the circumstances.

An example of a situation needing negotiation skills was described in the story of Shanti, a 64 year old Hindu woman with very painful metastatic breast cancer (Gelfand, Raspa, Briller, & Schim, 2005). Shanti was enrolled in an excellent hospice program, but was refusing all pain medication. Her strong Hindu belief that suffering was part of her karma created a significant conflict between herself, her immediate family members, and the hospice staff dedicated to the relief of suffering. As a result of good assessment and cultural understanding and with the help of a nurse who acted as a culture broker, Shanti’s husband and daughter were able to negotiate a dose of pain medication that would palliate just enough to allow clearer thinking without violating the client’s wishes.

The goal with negotiation is to arrive at a win-win solution that meets the needs of the patient and family, the provider, and institution or agency (Fisher & Ury, 1991). The very process of negotiation with the ongoing communication and assessment required demonstrates a profound commitment to understanding and advocating for client needs to be met to the maximum extent possible.

Explanation

The final, and least often needed, step of intervention is explanation. Explanation comes into play when efforts at appreciation, accommodation, and negotiation fail. This step would only be appropriate when assessment reveals that what the client, family, or community wants and needs is immoral, illegal, abusive, or unsafe in some way that puts it beyond the realm of negotiation.

It is difficult to think of examples where absolutely no accommodation or negotiation are possible – especially in the areas of end-of-life and palliative care services which are family-centered and relatively flexible compared to more traditional healthcare settings. It is conceivable, however, that a patient or family might request or demonstrate some behavior that cannot be tolerated. For example, the patient is requesting professional assisted suicide in a state where that is not legal or in a situation where the professional is morally opposed to the practice. In such as extreme example, the intervention must at least include a clear, honest, and respectful explanation of the reasons that a request cannot be met.

Explanation is seen as a last resort intervention that should be accompanied by re-assessment and renewed efforts to negotiate some middle ground. In the assisted suicide request, for example, the provider might negotiate for time to try more effective pain and symptom-relief measures to address underlying suffering rather than just denying the request and explaining the rationale. Attempts to change the client’s culture to fit with provider cultural expectations and are only undertaken when other interventions are not possible.

At all levels of intervention, from appreciation through explanation, the goal is to respect and honor individual personhood and cultural beliefs, values, and patterns and to find ways to bring the culturally-competent provider and the client together in meaningful culturally-congruent care. Of course, intervention needs to be followed by evaluation of effectiveness that then becomes assessment for the next round of care. Making mistakes can normally occur in the practice of healthcare and social service providers. Learning from personal errors and consciously requesting feedback from patients and families are hallmarks of the culturally competent. Admitting that we don’t have all the answers, but are very interested in how patients and families perceive our care and in what ways we can improve care for our next patient is both a wonderful way to learn and an excellent way to develop and maintain rapport across cultural boundaries.

Conclusion

We have described a model of culturally-congruent care and discussed ways to approach intervention for social workers, mental health professionals, nurses, and other health care workers caring for diverse patients, families, and communities. The model describes cultural diversity, cultural awareness, cultural sensitivity, and cultural competence variables for providers and several central domains of cultural similarity and difference at the client level. The model also addresses the presence and influence of systemic and organizational elements that create barriers to culturally-congruent care. Derived from this model, a systematic way to consider interventions is suggested. It is important for all members of the interdisciplinary health care team to work individually and collectively to improve cultural competence and to advocate for culturally-congruent care. Only by acknowledging the critical role that culture plays in human lives can we provide for appropriate care at life’s end.

Figure 2.

3-D Model with Cultural Confounders

Acknowledgments

This paper was partially supported by National Institute of Nursing Research Grant #NINR R21NR010725.

Contributor Information

Stephanie Myers Schim, College of Nursing, Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan, USA.

Ardith Z. Doorenbos, School of Nursing and School of Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA

References

- Abrums M. Faith and feminism: How African American women from a storefront church resist oppression in healthcare. Advances in Nursing Science. 2004;27:187–201. doi: 10.1097/00012272-200407000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abrums M, Leppa C. Beyond cultural competence: Teaching about race, gender, class, and sexual orientation. Journal of Nursing Education. 2001;40:270–275. doi: 10.3928/0148-4834-20010901-07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AHRQ (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services / Author; National healthcare disparities report:2008. 2009

- Allen DG. Whiteness and difference in nursing. Nursing Philosophy. 2006;7:65–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-769X.2006.00255.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson NLR, Ruiz CE, Fongwa MN. Community-based approaches to strengthen cultural competency in nursing education and practice. [Nursing education and workforce diversity] Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 2007;18(1):49S–59S. doi: 10.1177/1043659606295567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JF. Developing an English-as-a-second-language program for foreign-born nursing students at a historically black university in the United States. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 2008;19(2):184–191. doi: 10.1177/1043659607312973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkard AW, Knox S. Effect of therapist color-blindness on empathy and attributions in cross-cultural counseling. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2004;51:387–397. [Google Scholar]

- Campinha-Bacote J. A model and instrument for addressing cultural competence in health care. Journal of Nursing Education. 1999;38(5):203–207. doi: 10.3928/0148-4834-19990501-06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Census US. American Community Survey. 2005 Retrieved January 4, 2007, from http://factfinder.census.gov.

- Cintron A, Morrison RS. Pain and ethnicity in the United States: A systematic review. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2006;9(6):1454–1473. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coenen A, Doorenbos AZ, Wilson SA. Nursing interventions to promote dignified dying in four countries. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2007;34(6):1151–1156. doi: 10.1188/07.ONF.1151-1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen AB. Many forms of culture. American Psychologist. 2009;64(3):194–204. doi: 10.1037/a0015308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doorenbos AZ, Given CW, Given B, Verbitsky N. Symptom experience in the last year of life among individuals with cancer. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2006;32:403–412. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doorenbos AZ, Given B, Given CW, Wyatt G, Gift A, Rahbar M, Jeon S. The influence of end-of-life cancer care on caregivers. Research in Nursing & Health. 2007;30:270–281. doi: 10.1002/nur.20217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doorenbos AZ, Schim SM. Cultural competence in hospice. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Care. 2004;21(1):28–32. doi: 10.1177/104990910402100108. 80, 21p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doorenbos AZ, Schim SM, Benkert R, Borse NN. Psychometric evaluation of the cultural competence assessment instrument among healthcare providers. Nursing Research. 2005;54(5):324–331. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200509000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan KA, Labyak MJ. Hospice care: A model for quality end-of-life care. In: Ferrell BR, Coyle N, editors. Textbook of Palliative Nursing. New York: Oxford University Press; 2001. pp. 7–26. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher R, Ury WL. Getting to yes: Negotiating agreement without giving in (2nd ed.) New York: Penguin; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Fiske AP. Using individualism and collectivism to compare cultures - a critique of the validity of measurement of the constructs: Comment of Oyserman et all (2002) Psychological Bulletin. 2002;128:78–88. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.128.1.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortier JP, Bishop D. Setting the agenda for research on cultural competence in health care: Final report. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Minority Health; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Fried TR, Bradley EH, O'Leary J. Prognosis communication in serious illness: perceptions of older patients, caregivers, and clinicians. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2003;51:1398–1403. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51457.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelfand DE, Raspa R, Briller SH, Schim SM. End-of-Life stories: Crossing disciplinary boundaries. New York: Springer; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Giddings LS. Health disparities, social injustice, and the culture of nursing. Nursing Research. 2005;54:304–312. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200509000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giger JN, Davidhizar RE. Transcultural nursing: Assessment & Intervention. 4th ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Gray DP, Thomas DJ. Critical reflections on culture in nursing. Journal of Cultural Diversity. 2006;13:76–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griswold KS. Medical training in diversity: Disparity across cultures. State University of New York at Buffalo: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute 5K07HL085681-03; Medicine. 2006

- Gustafson DL. Transcultural nursing theory from a critical cultural perspective. Advances in Nursing Science. 2005;28:2–16. doi: 10.1097/00012272-200501000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haidet PM. Promoting physicians' cultural competence through reflective practice. Baylor College of Medicine - Houston TX: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute 5K07HL085622-03; Medicine. 2006

- Kumaş-Tan Z, Beagan B, Loppie C, MacLeod A, Frank B. Measures of cultural competence: Examining hidden assumptions. Academic Medicine. 2007;82(6):548–557. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3180555a2d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leininger MM. Culture care diversity and universality: A theory of nursing. New York: National League for Nursing; 1991. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leininger MM, McFarland M. Transcultural nursing: Concepts, theories, research, and practice. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Leiper J, Van Horn ER, Upadhyaya R. Promoting cultural awareness and knowledge among faculty and doctoral students. Nursing Education Perspectives. 2008;29(3):161–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mystakidou K, Tsilika E, Parpa E, Galanos A, Vlahos L. Caregivers of advanced cancer patients: feelings of hopelessness and depression. Cancer Nurs. 2007;30(5):412–418. doi: 10.1097/01.NCC.0000290807.84076.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Association of Social Workers. Indicators for the achievement of the standards for cultural competence in social work practice. 2007 Retrieved March 3, 2010 from http://www.socialworkers.org/practice/standards/NASWCulturalStandardsIndicators2006.pdf.

- National Center for Cultural Competence. The compelling need for cultural and linguistic competence. 2009 Retrieved April 1, 2009, 2009, from http://www11.georgetown.edu/research/gucchd/NCCC/foundations/need.html.

- National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization. NHPCO's Facts and Figures - 2005 Findings. 2005 Retrieved January 4, 2007, from http://www.nhpco.org/files/public/2005-facts-and-figures.pdf.

- National Institute of Nursing Research. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health; National Institute of Nursing Research Strategic Plan. 2006

- National Institute of Health. Bethesda, MD: State-of-the-Science Conference Statement on end-of-life care. 2004

- Neville H, Spanierman L, Doan B-T. Exploring the association between color-blind racial ideology and multicultural counseling competencies. Cultural Diversity and Ethnicity Minority Psychology. 2006;12:275–290. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.12.2.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purnell L. The Purnell model for cultural competence. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 2002;13(3):193–196. doi: 10.1177/10459602013003006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puzan E. The unbearable Whiteness of being (in nursing) Nursing Inquiry. 2003;10:193–200. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1800.2003.00180.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schim SM, Benkert R, Bell SE, Walker D, Danford C. Social justice; Added metaparadigm concept for urban health nursing. Public Health Nursing. 2007;24(1):73–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.2006.00610.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schim SM, Doorenbos AZ, Benkert R, Miller J. Culturally congruent care: Putting the puzzle together. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 2007;18(2):103–110. doi: 10.1177/1043659606298613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schim SM, Doorenbos AZ, Borse NN. Cultural competence among Ontario and Michigan healthcare providers. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2005;37(4):354–360. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2005.00061.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schim SM, Doorenbos AZ, Borse NN. Enhancing cultural competence among hospice staff. American Journal of Hospice & Palliative Medicine. 2006;23(50):404–411. doi: 10.1177/1049909106292246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schim SM, Doorenbos AZ, Miller J, Benkert R. Development of a cultural competence assessment instrument. Journal of Nursing Measurement. 2003;11(1):29–40. doi: 10.1891/jnum.11.1.29.52062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Joint Commission. Requirements related to the provision of culturally and linguistically appropriate health care. Oakbrook Terrace, IL: 2008. Apr, [Google Scholar]

- The Office of Minority Health, & U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. National Standards on Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services (CLAS) 2009 Retrieved April 1, 2009, 2009, from http://www.omhrc/gov/templates/browse.aspx?lvl=2&lvlID=15.

- Triandis HC. Culture and psychology: A history of the study of their relationships. In: Kitayana S, Cohen D, editors. Handbook of Cultural Psychology. New York: Guildford Press; 2007. pp. 59–76. [Google Scholar]