Abstract

Patients undergoing treatment for head and neck cancers have a myriad of distressing symptoms and treatment side effects which significantly alter communication and lower quality of life. Telehealth technology has demonstrated promise in improving patient-provider communication by delivering supportive educational content and guidance to patients in their homes. A telehealth intervention using a simple telemessaging device was developed to provide daily education, guidance, and encouragement for patients undergoing initial treatment of head and neck cancer. The goal of this article is to report the feasibility and acceptance of the intervention using both quantitative and qualitative measures. No eligible patients declined participation based on technology issues. Participants completed the intervention over 86% of the expected days of use. Direct nursing contact was seldom needed during the study period. Satisfaction with the technology and the intervention was very high. In this study a telehealth intervention was shown to be feasible, well accepted, and regularly used by patients experiencing extreme symptom burden and declining quality of life as a result of aggressive treatment for head and neck cancer.

INTRODUCTION

Treatment for head and neck cancer is most often a rigorous regimen of combination therapies producing a multitude of distressing symptoms and side effects. While it is nearly impossible to circumvent the physical and psychosocial insults caused by such treatment, some interventions directed towards educating and supporting patients during active treatment have met with success [1–4]. Conversely, other efforts have demonstrated little impact [5, 6] or have been poorly received [7] pointing to the need for effective, acceptable means to provide support during such difficult treatment.

Over the past ten years, telemedicine technology has enabled innovative approaches for improving patient education, assessment, support, and communication during treatment for both acute and chronic diseases. A recent policy white paper [8] described telemedicine technology as including “the electronic acquisition, processing, dissemination, storage, retrieval, and exchange of information for the purpose of promoting health, preventing disease, treating the sick, managing chronic illness, rehabilitating the disabled, and protecting public health and safety” (p.2). This same paper suggests that national telemedicine initiatives are essential to healthcare reform based upon their proven cost effectiveness and clinical efficacy. However, cost savings and clinical effectiveness will be unrealized outcomes if the interventions are not feasible in practice or acceptable to the targeted population.

In the arena of cancer care, telephone-based systems have been used to report and monitor cancer symptoms with favorable compliance noted even when patients are expected to initiate calls on a regular basis [9–12]. Favorable acceptance ratings have also been reported by both patients and clinicians regarding computerized systems used to assess symptoms and quality of life in cancer patients [13–19]. In the United Kingdom, a handheld computer system was successfully used to monitor and support patients receiving chemotherapy for lung or colorectal cancer [20], and a study testing a dialogic model of cancer care expecting patients to respond to telehealth messaging on a daily basis over six months reported an 84% cooperation rate [21]. In these studies, the majority of patients reported ease of use and acceptability of the technology. Survey research has found both urban and rural cancer patients to be receptive to receiving medical and psychiatric services via telehealth [22].

Published reports describing use of telehealth and computerized interventions during head and neck cancer treatment are less prevalent. Touch screen computers were successfully used in the Netherlands to collect quality of life and distress data from head and neck cancer patients [16]. Videoconferencing has been used successfully to overcome geographical barriers to patient assessment [23–25] and to provide speech-language pathology services to people living with head and neck cancers in remote areas. Reported use of telehealth management appears promising for providing timely access to care for those who are geographically isolated [26].

A research group based in the Netherlands developed and tested a comprehensive electronic health information support system for use in head and neck cancer care [27]. The system had four patient-related functions: facilitating communication between patients and healthcare providers; providing information about the disease and its treatment; connecting patients with patients similarly diagnosed; and monitoring patients after hospital discharge. The system was found to be well-accepted and appreciated by participating patients, and its use enabled early identification and direct intervention for patient problems [27]. A clinical trial of the telehealth application showed improved quality of life in 5 of 22 studied parameters for the treatment group [28]. However, twenty of the 59 patients eligible for the intervention group refused participation; eleven (55%) of these stated computer related concerns as their reason for non participation.

Knowing that head and neck cancer patients experience a high burden of illness and often have significant communication, socioeconomic, and geographic barriers to care, our team developed a telehealth intervention using a simple telemessaging device to circumvent communication barriers and perceived technical challenges associated with computer-based systems to provide education and support to patients in their own home and on their own time schedule[29]. Overall, we hypothesized that patients receiving the intervention would experience less symptom distress, improved quality of life, increased self-efficacy, and greater satisfaction with symptom management than those in the control group. However, as a first step toward examining the efficacy and effectiveness of this intervention, this study examined both quantitative and qualitative indicators of its feasibility and acceptance among patients undergoing treatment for head and neck cancer.

Methods

Design

Subsequent to study approval by the University of Louisville's Human Subjects Protection Office, a randomized clinical trial comparing the telehealth intervention to standard care was conducted using a two-group parallel design. This study reports on the intervention's feasibility and acceptance in the treatment group of 44 patients.

Site

Participants were recruited from patients receiving care from the Multidisciplinary Head and Neck Cancer Team at the James Graham Brown Cancer Center (JGBCC) over a two year period (June, 2006 through June, 2008). The team consisted of head and neck surgeons, medical oncologists, radiation oncologists, nurses, a pathologist, a speech therapist, a registered dietician, a psychologist, and a social worker. This team developed a comprehensive assessment and treatment plan during each patient's initial visit to the clinic and coordinated patient care throughout the treatment process.

Sample

Patients eligible for study participation met the following inclusion criteria: (1) initial diagnosis of Head or Neck Cancer including cancers of the oral cavity, salivary glands, paranasal sinuses and nasal cavity, pharynx and larynx; (2) involvement in a treatment plan including one or more modalities (i.e., surgery, chemotherapy, radiation or any combination); (3) capacity to give independent informed consent; and (4) ability to speak, read and comprehend English at the eighth grade level or above. Patients were excluded from participation if they had no land telephone line, had a thought disorder, were incarcerated or had compromised cognitive functioning.

All patients scheduled for assessment received an explanation of the research study via print materials prior to their first clinic visit. During their first scheduled clinic visit, all patients identified as eligible were approached by a member of the research study staff who briefly explained the study and asked if they might be interested in study participation. Because of the stress and content of this first clinic visit, interested patients were contacted later by phone to schedule an additional visit to review the study and obtain informed consent.

During the informed consent meeting, the study procedures were explained in detail. If the patient agreed and signed a consent form, a randomization grid which considered the patient's particular treatment plan was used to assign the patient to either the control or experimental group. Baseline data was also collected during this first visit.

Description of the Intervention

The technology selected for implementing the intervention was the Health Buddy® System, a commercially available, proprietary system produced and maintained by Robert Bosch Healthcare, Inc. The Health Buddy®, the appliance used for interaction between the participant and the healthcare provider, is a user-friendly, easily visible, electrical device that attaches to the user's land phone line (see Figure 1). Questions and information are displayed on the liquid crystal display (LCD) screen of the 6 × 9 inch appliance. The individual responds to questions by pressing one of the four large buttons below the screen. The research team selected the technology provider based on the ability of the technology to perform in accordance with the research objectives.

Figure I. The Health Buddy® Appliance.

The 6×9 inch, easily visable appliance attaches to the user's land phone line and provides a user-friendly interface between patient and healthcare provider.

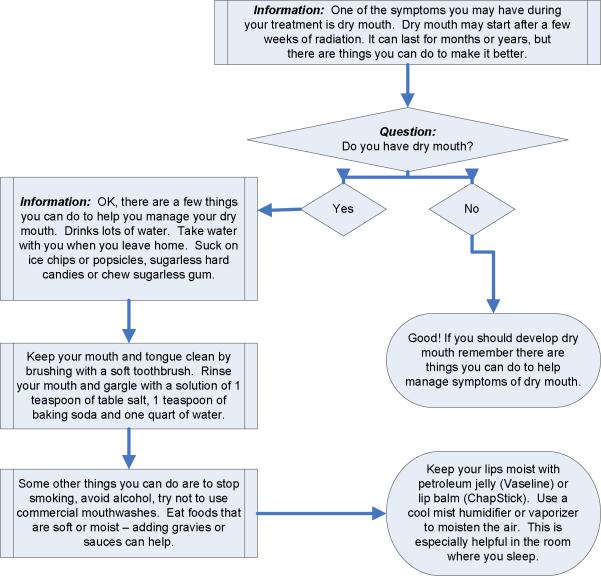

Symptom control algorithms developed using participatory action research (surveys of current and past patients and clinicians) and evidence based practice were programmed into the telehealth messaging system (see article by Head et al, 2009 which details the algorithm topic selection and development process [29]). The algorithms addressed 29 different symptoms and side effects of treatment consisted of approximately 100 questions accompanied by related educational and supportive responses. Patients were asked 3–5 questions daily related to the symptoms anticipated during their treatment scenario. Depending upon their response, they would receive specific information related to symptom self-management, including recommendations as to when to contact their clinicians. The algorithms were constructed with the goal of encouraging self-efficacy and independent action on the part of the participant. See Figure 2 for an example of the branching algorithms.

Figure 2. Sample Algorithm.

Participants randomly assigned to the treatment group immediately had the Health Buddy® connected to a land telephone line in their home. Most (40%) chose to place it in their kitchen while another 26% placed it in their bedrooms; most often, it was in a highly visible location serving to remind the participant to respond. Research study staff delivered, installed, and demonstrated how to operate the equipment. Installation was simple and required only minutes. A tutorial programmed into the Health Buddy® taught participants how to reply to questions appearing on the monitor using the four large keys below the possible answers or rating scale which would appear depending on the type of question asked.

During the early hours of the morning, the device would automatically call a toll free number. Responses to the previous day's questions were uploaded and questions and related information for the next day were downloaded over the telephone line onto a secure server. Phone service was never disrupted by the device; if the phone was in use, the system would connect later to retrieve and download information. Once new content was transferred, a green light on the device would flash to alert the participant that new questions were available for response. Once the participant pressed any of the keys, the new algorithms would begin appearing on the monitor screen.

Participants were instructed to begin responding on the first day they received treatment or on the first day after returning home from surgery. They were asked to continue responding daily (unless hospitalized for treatment) throughout the treatment period and for approximately two weeks post treatment as treatment induced symptoms continue during that period of time. Study staff contacted participants when treatment was complete and scheduled a date to pick up the appliance and end daily responding. Daily patient responses required 5–10 minutes.

Participant responses could be viewed by study staff via Internet access one day after being answered. Responses were monitored daily by study nurses. Symptoms unrelieved over time or symptoms targeted as requiring immediate intervention (i.e., serious consideration of suicide) would result in the study nurse contacting the patient directly by phone and/or contacting clinicians to assure immediate intervention. However, it is important to note that this direct intervention by study staff was infrequent as most symptoms were addressed independently by the participant as desired. If a participant had not reported a period of planned hospitalization and did not respond for three consecutive days, study staff would contact the patient by phone to ascertain the reason for noncompliance.

Measures

The following indicators were selected as measures of acceptance (accrual rate), feasibility (utilization, nurse initiated contacts), and/or satisfaction (satisfaction ratings)., Narrative responses and a post-study survey provided additional data examining acceptance, feasibility and satisfaction with the intervention. In addition, demographic and medical information as well as measures assessing primary study outcomes were collected from each participant. Table 1 lists all measures and the study time point when they were administered.

Table 1.

Study Measures by Time Point

| Measures | Pre Treatment | During Treatment | Post Treatment | Cummulative |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | X(baseline) | X | ||

| Accrual Rate | X | |||

| Utilization Rate | X | |||

| FACT-H&N | X(baseline) | X (mid-tx) | X (2–4wks post-tx) | |

| MSAS | X(baseline) | X (mid-tx) | X (2–4 wks post-tx) | |

| Satisfaction with Technology | X | |||

| Nurse Initiated Contacts | X | |||

| Exit Interview | X (end of treatment) | |||

| Post-Study Written Survey | X (60–90 days post-tx) |

Accrual Rate

The number of individuals assessed for study eligibility, reasons for exclusion or noncompletion and numbers included in analysis were all recorded to examine acceptance of the intervention and identify issues with the intervention or technology affecting participation.

Utilization

Feasibility was operationalized as device utilization using the percentage of days on which a participant responded to the Health Buddy. This was calculated using the number of days the participant responded to the telehealth device divided by the number of days the participant had the device and was expected to respond. This data was maintained and provided by the telehealth provider (Robert Bosch Healthcare, Inc.).

Nurse Initiated Contacts with Participants and/or Clinicians

The number of occasions on which a nurse decided to intervene was used as an indicator of feasibility under the premise that the goal of the intervention was to support and encourage patient-driven efforts to seek care for persistent or troubling symptoms. If a patient reported a symptom, they were given management information and encouraged to discuss problems further with their clinician either by phone or during clinic visits. If a patient continued to report an unresolved symptom or if the symptom required immediate intervention (i.e., suicide threat), the research nurse reviewing responses would contact the patient and/or clinician to ascertain why and/or assist with its resolution. These nurse initiated contacts should be infrequent if the intervention is achieving the goal of developing patient self-efficacy.

Satisfaction Ratings

Items assessing satisfaction with the technology were also administered to participants via the telehealth messaging device. Questions related to satisfaction with the initial setup of the telehealth appliance were asked at the beginning of the intervention. Ongoing satisfaction with the device, messaging content, and the health care provider was assessed every 90 days. The specific questions asked are detailed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Participant Demographic and Medical Information

| Frequency | Valid Percent | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender (n=44) | ||

| Male | 39 | 88.6 |

| Female | 5 | 11.3 |

| Race (n=44) | ||

| Caucasian | 40 | 90.9 |

| African American | 4 | 9.0 |

| Tumor stage (n= 44) | ||

| Stage I | 7 | 15.9 |

| Stage II | 15 | 34.0 |

| Stage III | 11 | 25.0 |

| Stage IV | 4 | 9.0 |

| Unable to Determine | 5 | 11.4 |

| Unknown | 2 | 4.5 |

| Site of Cancer (n=44) | ||

| Larynx | 12 | 27.2 |

| Tongue, Base of tongue | 7 | 15.9 |

| Unknown primary | 7 | 15.9 |

| Tonsillar | 4 | 9.0 |

| Other, H&N sites | 14 | 31.8 |

| Insurance Status (n= 44) | ||

| No Insurance | 8 | 18.2 |

| Medicaid | 1 | 2.3 |

| Medicare | 2 | 4.5 |

| Medicaid & Medicare | 1 | 2.3 |

| Medicare & Supplement | 9 | 20.5 |

| Medicare & VA Benefits | 2 | 4.5 |

| Veteran Benefits Only | 6 | 13.6 |

| Private Insurance | 15 | 34.1 |

| Highest Educational Degree (n=20) * | ||

| Less than High School | 3 | 15.0 |

| High School or GED | 9 | 45.0 |

| Associate/Bachelor's Degree | 4 | 20.0 |

| Masters, PhD or MD | 2 | 10.0 |

| Other | 2 | 10.0 |

| Income Range (n=18) * | ||

| $20,000 or less | 5 | 27.8 |

| $20,001 – 50,000 | 5 | 27.8 |

| $70,001 – 100,000 | 5 | 27.8 |

| Over $100,000 | 3 | 16.7 |

| Per cent of poverty in zip code area (n=44) | ||

| 2.8 – 5.1% | 11 | 25.0 |

| 5.9 – 8.6 % | 11 | 25.0 |

| 9.0 – 11.9 | 10 | 22.7 |

| 12.3 – 45.9 | 12 | 27.2 |

Data not available on all participants

Narrative Data

Upon completion of the intervention, participants in the treatment group completed an exit interview using open-ended questions regarding the utility of the intervention, relevance of the algorithms, value or burden of item repetition in the algorithms, symptoms or problems experienced that were not addressed by the intervention, and general comments.

Post-Study Survey

A final survey was mailed to participants several months after completion of the study asking for additional feedback about the impact of the intervention. Specifically, participants (both treatment and control groups) were asked about their overall satisfaction with the treatment and services at the cancer center, their satisfaction with information received about their treatment, the response(s) received when they attempted contact with health care team after hours, the amount of support received, their current smoking and alcohol usage, and several demographic questions not earlier assessed or available through record review (years of education, highest degree, income range). Those receiving the intervention were also asked about the impact of the Health Buddy® on their care and actions taken in response to the algorithms.

Demographic and Medical Information

Demographic information was collected using the initial survey, and information about the participant's medical history, condition, treatments received, treatment timing, complications, comorbidities and treatment response was collected via retrospective medical record review subsequent to completion of the clinical trial.

Outcome Measures

While outcomes of the clinical trial are not the subject of this article, the results of quality of life and symptom burden measures for the treatment group only are included here because of their relationship with device utilization. The two measures included the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy – Head and Neck Scale (FACT-H&N) and the Memorial symptom Assessment Scale (MSAS) and were administered at baseline (before beginning treatment), mid-treatment and post treatment.

Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy – Head and Neck Scale (FACT-H&N)

The FACT-G (general) is a multidimensional quality of life instrument designed for use with all cancer patients. The instrument has 28 items divided into four subscales: functional well-being, physical well-being, social well-being, and emotional well-being. This generic core questionnaire was found to meet or exceed requirements for use in oncology based upon ease of administration, brevity, reliability, validity, and responsiveness to clinical change [30]. Added to the core questionnaire is the Head and Neck specific subscale consisting of eleven items specific to this cancer site. A Trial Outcome Index (TOI) is also scored and is the result of the physical, functional and cancer specific subscales. List et al., [31] found the FACT-H&N to be reliable and sensitive to differences in functioning for patients with Head and Neck Cancers (Cronbach's alpha for total FACT-G was .89 and for the Head and Neck subscale was 0.63 in this study of 151 patients). Additionally, head and neck cancer patients found the FACT-H&N relevant to their problems and easy to understand, and it was preferred over other validated head and neck cancer QOL questionnaires [32]. The FACT H&N was chosen for this study because it: (1) is nonspecific related to a treatment modality or subsite among head and neck cancers; (2) allows comparison across cancer diagnoses while still probing issues specific to head and neck cancer; (3) is short and can be completed quickly; (4) includes the psychosocial domains of social/family and emotion subscales as well as physical and functional areas; and (5) is self-administered.

Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale (MSAS)

This multidimensional scale measures the prevalence, severity and distress associated with the most common symptoms experienced by cancer patients. Physical and emotional subscale scores as well as a Global Distress Index (GDI – considered to be a measure of the total symptom burden) can be generated from patient responses. The MSAS has demonstrated validity and reliability in both in and outpatient cancer populations [33–35]. Initial psychometric analysis by Portenoy et al., used factor analysis to define two subscales: psychological symptoms and physical symptoms with Cronback α coefficients of 0.88 and 0.83 respectively; convergent validity was also established [34]. It was chosen for this study because of its proven ability to measure both the presence and the intensity f experienced symptoms [33, 35–38].

Data Analysis

Quantitative data was documented and analyzed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), version 16. Descriptive statistics were calculated to describe the sample and assess study outcomes, including feasibility and acceptability of the intervention. To ascertain relationships between usage of the device and demographic and medical information, a series of correlational analyses using Spearman's rho were conducted. This nonparametric test was chosen over the Pearson's r because of the small sample size, the lack of a normal distribution for several of the variables, and the ordinal nature of several of the variables. Multiple regression analyses were also planned, but lack of significant bivariate correlations precluded multivariate analysis.

Qualitative responses to open-ended questions were analyzed to identify themes and direct quotations illustrating those themes.

Descriptive analysis of the treatment group's responses to the outcome measures (quality of life and symptom burden) was done to ascertain changes over the course of the intervention using the mean scores at baseline, during and post treatment.

Results

Description of Participants

Participants randomly assigned to the intervention group (N = 45) were an average age of 59 years (±11.7), and most were covered by private (34%) or public (48%) insurance. On average, participants had completed 13.5 years (±3.0) of formal education. Thirty-nine (87%) of the participants were male and 91% were Caucasian

With regard to medical information, participants were predominantly diagnosed with stage II cancers of the head and neck (36%). The most prevalent site was larynx (12 patients) followed by tongue and base of tongue (7 patients) and unknown primary (7 patients). The vast majority received chemotherapy (32 or 71%) and/or radiation (42 or 93%).

Additional details regarding demographic and medical characteristics of the sample are provided in Table 2.

Feasibility and Acceptability

Accrual Rate

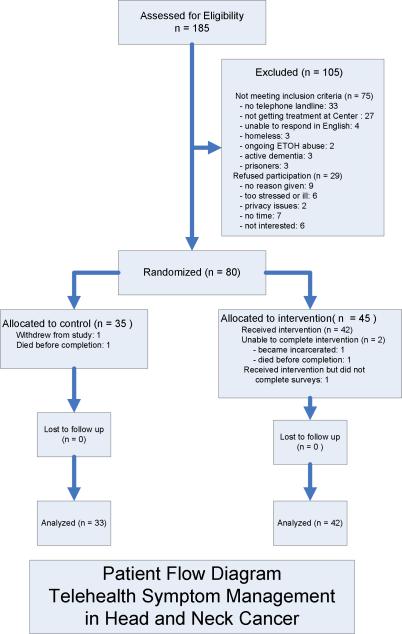

Of the 185 patients assessed for eligibility during the two year recruitment period, 105 were excluded. See Figure 3 for a detailed depiction of study accrual for both the treatment and control groups. Thirty-three (31%) were excluded because they did not have a land phone line, a requirement for transmitting the algorithms to the Health Buddy® appliance. Most of these had cell phones only. No potential participants refused participation due to issues related to operation of the technology itself.

Figure 3. Accrual Flow Chart.

Device Utilization

Participants used the telehealth device for an average of 70.7 days (±26.7), which constituted 86.3% (±15.0) of the total days available for use. Of note, the median percentage of use was 94.2% and the modal percentage was 100%, indicating that the vast majority of participants consistently used the telehealth device. The participant with the lowest usage rate used the device 46% of the days available.

By far, the most common reason for Health Buddy® non-response was due to patient hospitalization. Two subjects traveled out-of-town frequently on weekends and would leave the Health Buddy® at home. One subject had accidentally unhooked the Health Buddy® and a home visit was made to re-connect the device into the patient's phone line.

Nurse Initiated Contacts with Participants and/or Clinicians

Of the 45 enrolled patients, 33 required additional contact with a research nurses (See Table 3). The most common reasons patients were contacted were due to non-response for 3 consecutive days (38.3%), repeated reporting of high levels of unrelieved pain (30%), and suicidal thoughts (10%). In all, 120 calls were placed: one call for every 25.9 response days. In every case, the problem was resolved.

Table 3.

Nurse Initiated Calls to Participants

| Number of Patients | Problem | Outgoing Calls | Resolution |

|---|---|---|---|

| 15 | No Response on Health Buddy® for 3 Consecutive Days | 46 | Patient Teaching |

| 17 | Pain Related Issues | 36 | Advocacy / Referral / Patient Teaching |

| 5 | Suicidal Thoughts | 12 | Advocacy / Referral |

| 7 | G-tube Problems | 8 | Patient teaching |

| 5 | Sadness / Depression | 6 | Advocacy / Referral |

| 3 | Multiple symptoms | 3 | Advocacy / Referral |

| 3 | Nausea/Vomiting | 4 | Referral / Patient Teaching |

| 2 | Coughing/Excessive Secretions | 2 | Patient Teaching |

| 2 | Constipation | 2 | Patient Teaching |

| 1 | Stomatitis | 1 | Referral |

Satisfaction Ratings

Responses to surveys programmed into the Health Buddy® system are displayed in Table 4. Overall, respondents responded favorably finding installation to be easy, the content to be helpful, and the overall experience to be positive.

Table 4.

Participant Satisfaction Ratings Survey 60 Days into Intervention (N=44)

| Percent of Respondents | |

|---|---|

| Installation Satisfaction | |

| Installation Problems? | |

| Yes | 2 |

| No | 98 |

| Any difficulty completing the first training questions? | |

| Yes | 7 |

| No | 94 |

| Length of Installation? | |

| 2–5 minutes | 52 |

| 6–10 minutes | 41 |

| 11–15 minutes | 4 |

| 16–20 minutes | 2 |

| Content Satisfaction | |

| Overall, I think the Health Buddy® questions are: | |

| Very Easy | 44 |

| Somewhat easy | 16 |

| Neutral | 32 |

| Somewhat difficult | 4 |

| Difficult | 4 |

| Repeating questions reinforced knowledge and understanding | |

| Strongly agree | 56 |

| Somewhat agree | 28 |

| Neutral | 12 |

| Somewhat disagree | 4 |

| Strongly disagree | 0 |

| Understanding of my health condition | |

| Much better | 64 |

| Somewhat better | 20 |

| Neutral | 16 |

| Somewhat worse | 0 |

| Much worse | 0 |

| Managing my health condition | |

| Much better | 52 |

| Somewhat better | 44 |

| Neutral | 4 |

| Somewhat worse | 0 |

| Much worse | 0 |

| Recommend the devise to others | |

| Very willing | 80 |

| Somewhat willing | 12 |

| Neutral | 4 |

| Somewhat unwilling | 0 |

| Very unwilling | 4 |

| Overall Satisfaction | |

| Satisfaction with device | |

| Very satisfied | 45 |

| Satisfied | 35 |

| Somewhat satisfied | 15 |

| Not very satisfied | 5 |

| Satisfaction with the communication between you and your doctor or nurse | |

| More satisfied | 65 |

| No difference | 30 |

| Less satisfied | 5 |

| Ease of using the device | |

| Very easy | 85 |

| Easy | 15 |

| Not easy | 0 |

| Overall experience with the device | |

| Positive | 85 |

| Neutral | 15 |

| Negative | 0 |

| Continue to use the device | |

| Very likely | 40 |

| Likely | 40 |

| Somewhat likely | 15 |

| Not very likely | 0 |

Narrative Comments

During the exit interview, participants were asked, “How was having the Health Buddy® helpful to you?” Responses could be categorized into two major themes: (1) the Health Buddy® provided needed information, and (2) the Health Buddy® improved my self-management during treatment.

Statements made related to the information provided included:

-

-

it gave me information on what could be expected from treatment

-

-

it was a constant reminder of things to watch for

-

-

it kept me abreast of my total condition at all times

-

-

it kept me informed

-

-

it gave good directions so I didn't have to ask at the Cancer Center

-

-

it gave good suggestions on treatments (home remedies) such as gargles, care of feeding tube, exhaustion, and everyday symptoms

Statements made indicative that the Health Buddy® improved self management included:

-

-

I learned what I could do to make myself feel better

-

-

it helped me manage my symptoms

-

-

it taught me about symptom management and how to handle problems

-

-

it let me know whether to contact a doctor or use self-care

-

-

it gave me who to call for problems and some things to try

-

-

it kept me aware of what I needed to do in order to make the period easier

-

-

it reminded me to take my meds and exercise

Additionally, some participants noted the support they felt from having the Health Buddy® interventions during treatment in saying:

-

-

it kind of helped my depression through acknowledging it and giving me something to do

-

-

it helped me feel safe

-

-

it made me feel I was not the only one who had experience with these things

-

-

it comforted me because I knew what was going to happen

Post-Study Survey

Twenty (45%) of the 44 patients who received the intervention responded to the mailed post study survey.

When asked if they felt they received better care because they had the device, 13 of the 20 (65%) responded that they did. Eighteen (90%) of the treatment group responders stated they were very satisfied with their care (one stated “somewhat satisfied”) and 20 (100%) said they would recommend the Cancer Center for treatment. Nineteen (95%) stated they received adequate support during treatment.

Outcome Measures

Mean scores on the FACT-H&N and subscales, and the MSAS and subscales taken pre, during and post treatment are displayed in Table 5. As expected, average QOL scores declined during treatment while symptom distress increased with a return to near baseline scores post-treatment.

Table 5.

Treatment Group Mean Scores on Outcome Measures (N=44)

| Scale/subscale | Pre-tx | During Treatment | Post-tx |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total FACT-H&N | 100.3 | 85.6 | 101.5 |

| FACT-G | 74.3 | 69.4 | 78.5 |

| Trial Outcome Index | 62.6 | 46.0 | 65.0 |

| Physical Well-being Subscale | 21.2 | 17.6 | 21.1 |

| Functional Well-being Subscale | 15.6 | 12.5 | 17.4 |

| Emotional Well-being Subscale | 21.1 | 22.3 | 22.2 |

| Social Well-being Subscale | 21.1 | 22.3 | 22.2 |

| Total MSAS | .7 | 1.1 | .8 |

| Global Distress Index | 1.1 | 1.8 | 1.3 |

| Physical Subscale | .7 | 1.5 | 1.1 |

| Psychological Subscale | 1.1 | 1.2 | .8 |

Correlations

The relationships between percentage usage per patient and the following variables were evaluated: age, income, years of education, tumor stage and percent poverty in patient's zip code. Percent poverty in zip code area was intended to be a surrogate measure of the patient's socioeconomic status. Results are displayed in Table 6. No significant correlations were noted although years of education and percentage poverty in zip code showed a trend towards significance.

Table 6.

Relationships between Select Variables and Usage Percentage

| Variable (vs. % usage) | Relationship | |

|---|---|---|

| Spearman's rho rs | Significance (1-tailed) | |

| Percent poverty in zip code | .213 | .083 |

| Age | .146 | .173 |

| Years of Education | −.325 | .081 |

| Income | −.292 | .120 |

| Tumor Stage | .196 | .122 |

| Physical Well-being (during tx) | .310 | .048 |

| Emotional Well-being (during tx) | .315 | .042 |

Although a multivariate model was planned, the lack of significant bivariate correlations precluded the need for multivariate analysis.

When percent usage was correlated with FACT-H&N total and subscales taken at baseline, during active treatment and post treatment, significant positive correlations were found between the percentage used and the Physical Well-being subscale score during treatment ( Spearman's rho = .310, p =.048) and between percentage used and the Emotional Well-being subscale during treatment (Spearman's rho = .315, p = .042).

There were no significant correlations between percentage usage and the scores on the MSAS.

Discussion

Both qualitative and quantitative measures indicate that using telehealth to support symptom management during aggressive cancer treatment is both feasible and well-accepted. Patient users were not intimidated by this particular technology as it was simple to set up and use and required no previous computer training to operate. The Health Buddy® was viewed as providing important and useful information. Overall, users felt that it improved their ability to self-manage their disease and the side effects of treatment, and provided a sense of support and security.

Unlike other studies which use telehealth devices to monitor patient symptoms, our goal was to increase patient self-management of the symptoms experienced during intensive medical treatment therefore avoiding increased burden on the medical system. The fact that the research nurse overseeing the responses needed to intervene only once every 25.9 days speaks to the ability of the intervention to have a positive impact on utilization of medical services.

The lack of significant relationships between usage and descriptive variables such as age and years of education suggests that the intervention was equally acceptable to all subgroups. Factors such as age, previous computer literacy, educational obtainment, and socioeconomic status did not significantly differentiate our study population in terms of compliance as verified by usage percentages.

The significant relationships found between the percentage used and the subscale scores on Physical Well-being and Emotional Well-being during treatment may indicate that increased use of the telemessaging intervention during treatment resulted in better physical and emotional aspects of quality of life.

The high rate of daily compliance with the intervention in spite of differentiating personal variables and the severity of the treatment regimen may have been due to one or a combination of the following factors:

-

-

the simplicity of the technology

-

-

the visibility of the appliance (often place in the kitchen or living area of the home) and its flashing green light as cues to the need to respond

-

-

the usefulness of the information provided

-

-

the use of simple messaging language presented in an encouraging, positive manner

-

-

affirmations related to application of the symptom management protocols suggested

-

-

curiosity related to the day's messaging and the motivational saying which always appeared at the end

-

-

knowledge that someone was reviewing the responses, tracking and intervening when the participant did not respond for several days

Our study supports the benefits of telehealth interventions noted by providers in a study by Sandberg (2009): opportunities for more frequent contact; greater relaxation and information due to the ability to interact in one's own home; increased accessibility by those frequently underserved and timely medical information and monitoring [39]. Similar to the study done in the Netherlands [27, 28], this study noted technological problems as the primary disadvantage, but, in our intervention, we had no problems with the technology or equipment.

Although computerized technology served as a barrier to previous telehealth research, the lack of a land-based phone line was a factor preventing participation in the current study. Indeed, many participants maintained only wireless communication devices which were not compatible with the version of the Health Buddy® that was employed in this study. However, improvements in the technology since completion of this study now allow for wireless access to the appliance or provision of an independent wireless messaging device for those without such access in their own homes.

Although the data generally support the feasibility and acceptability of the telehealth-based intervention, the results should be interpreted in the context of a few study limitations. In particular, the sample size was somewhat small, and data pertaining to the socioeconomic status of participants was not available for all participants. Second, the study did not include measures of the patient's direct interactions with their healthcare providers during the study or specific data related to their health care utilization (e.g., emergency room visits, preventable inpatient hospitalizations, emergency calls to clinicians). The collection of more exhaustive measures of healthcare utilization was limited by resources but is planned for subsequent studies. Finally, concerns regarding subject burden limited assessment of the usability of the telehealth device.

Although compliance with utilization expectations and completion of study measures was excellent during the course of the intervention, response to the follow-up survey mailed several months later was less than 50%. This low response rate was most likely due to several factors: (1) this survey was sent at the conclusion of the entire study (by this time, patients were from 0–21 months past their active participation); (2) it was a mailed survey with no additional contact or follow-up effort to increase response rate; (3) participants may have felt that they had already shared their opinions in the exit interview and may have felt overburdened by study measures at this point out; and (4) participants may have died, moved or been medically able to respond. This lack of response did limit our ability to evaluate the longitudinal impact of the intervention.

Conclusions

This telehealth intervention proved to be an acceptable and feasible means to educate and support patients during aggressive treatment for head and neck cancer. Patient compliance with telehealth interventions during periods of extreme symptom burden and declining QOL is feasible if simple technology cues the patient to participate, offers positive support and relevant education, and is targeted or tailored to their specific condition.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was funded in part by a grant from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health.

This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the Louisville Veterans Affairs Medical Center.

Equipment and technical systems were provided through a contract with Robert Bosch Healthcare, Inc.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

DISCLAIMER: Contents of this article do not represent the views of the Department of Veteran Affairs or the federal Government.

The researchers report no conflict of interest related to the technology used in this study.

References

- 1.Llewellyn CD, McGurk M, Weinman J. Are psycho-social and behavioural factors related to health related-quality of life in patients with head and neck cancer? A systematic review. Oral Oncology. 2005;41(5):440–54. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2004.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vakharia KT, Ali MJ, Wang SJ. Quality-of-life impact of participation in a head and neck cancer support group. Otolaryngology - Head & Neck Surgery. 2007;136(3):405–10. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2006.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allison PJ, et al. Results of a feasibility study for a psycho-educational intervention in head and neck cancer. Psycho-Oncology. 2004;13:482–485. doi: 10.1002/pon.816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karnell LH, et al. Influence of social support on health-related quality of life outcomes in head and neck cancer. Head & Neck. 2007;29(2):143–6. doi: 10.1002/hed.20501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Petruson KM, Silander EM, Hammerlid EB. Effects of psychosocial intervention on quality of life in patients with head and neck cancer. Head & Neck. 2003;25(7):576–84. doi: 10.1002/hed.10243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.deLeeuw JRJ, et al. Negative and positive influences of social support on depression in patients with head and neck cancer: A prospective study. Psycho-Oncology. 2000;9:20–28. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1611(200001/02)9:1<20::aid-pon425>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ostroff J, et al. Interest in and barriers to participation in multiple family groups among head and neck cancer survivors and their primary family caregivers. Family Process. 2004;43(2):195–208. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2004.04302005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bashshur RL, et al. National telemedicine initiatives: Essential to healthcare reform. Telemedicine and e-Health. 2009;15(6):1–11. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2009.9960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davis K, et al. An innovative symptom monitoring tool for people with advanced lung cancer: A pilot demonstration. Supportive Oncology. 2007;5(8):381–387. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mooney KH, et al. Telephone-linked care for cancer symptom monitoring: A pilot study. Cancer Practice. 2002;10(3):147–54. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5394.2002.103006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Friedman RH, et al. The virtual visit: Using telecommunications technology to take care of patients. Journal of the American Medical INformatics Association. 1997;4:413–425. doi: 10.1136/jamia.1997.0040413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weaver A, et al. Application of mobile phone technology for managing chemotherapy-associated side-effects. Annals of Oncology. 2007;18(11):1887–92. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berry D, et al. Computerized symptom and quality-of-life assessment for patients with cancer Part 1: Development and pilot testing. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2004;31(5):E75–E83. doi: 10.1188/04.ONF.E75-E83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mullen K, Berry D, Zierler B. Computerized symptom and quality-of-life assessment for patients with cancer Part II: Acceptability and usability. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2004;31(5):E84–E89. doi: 10.1188/04.ONF.E84-E89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fortner B, et al. The Cancer Care Monitor: Psychometric content evaluation and pilot testing of a computer administered system for symptom screening and quality of life in adult cancer patients. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2003;26(6):1077–1092. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2003.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Bree R, et al. Touch screen computer-assisted health-related quality of life and distress data collection in head and neck cancer patients. Clinical Otolaryngology. 2008;33(2):138–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-4486.2008.01676.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang H, et al. Developing a computerized data collection and decision support system for cancer pain management. CIN: Computers, Informatics, Nursing. 2003;21(4):206–217. doi: 10.1097/00024665-200307000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilkie DJ, et al. Usability of a computerized PAINReportIt in the general public with pain and people with cancer pain. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2003;25(3):213–224. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(02)00638-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kroenke K, et al. Effect of telecare management on pain and depression in patients with cancer: A randomized trial. JAMA. 2010;304(2):163–171. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kearney N, et al. Utilizing handheld computers to monitor and support patients receiving chemotherapy: Results of a UK-based feasibility study. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2006;14(7):742–52. doi: 10.1007/s00520-005-0002-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chumbler NR, et al. Remote patient-provider communication and quality of life: Empirical test of a dialogic model of cancer care. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare. 2007;13:20–25. doi: 10.1258/135763307779701112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grubaugh AL, et al. Attitudes toward medical and mental health care delivered via telehealth applications among rural and urban primary care patients. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2008;196(2):166–170. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e318162aa2d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stalfors J, et al. Accuracy of tele-oncology compared with face-to-face consultation in head and neck cancer case conferences. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare. 2001;7:338–343. doi: 10.1258/1357633011936976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dorrian C, et al. Head and neck cancer assessment by flexible endoscopy and telemedicine. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare. 2009;15:118–121. doi: 10.1258/jtt.2009.003004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stalfors J, et al. Haptic palpation of head and neck cancer patients - Implications for education and telemedicine. Studies in Health Technology and Informatics. 2001;81:471–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Myers C. Teleheatlh applications in head and neck oncology. Journal of Speech-Language Pathology and Audiology. 2005;29(3):125–127. [Google Scholar]

- 27.van den Brink JL, et al. Involving the patient: A prospective study on use, appreciation and effectiveness of an information system in head and neck cancer care. International Journal of Medical Informatics. 2005;74(10):839–849. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2005.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van den Brink JL, et al. Impact on quality of life of a telemedicine system supporting head and neck cancer patients: a controlled trial during the postoperative period at home. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 2007;14(2):198–205. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M2199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Head B, et al. Development of a telehhealth intervention for head and neck cancer patients. Telemedicine and E-Health. 2009;15(1):100–108. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2008.0061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cella DF, et al. The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT) Scale: Development and validation of the general measure. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 1993;11(3):570–579. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.3.570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.List MA, et al. The Performance Status Scale for Head and Neck Cancer Patients and the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Head and Neck Scale. A study of utility and validity. Cancer. 1996;77(11):2294–301. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19960601)77:11<2294::AID-CNCR17>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mehanna HM, Morton RP. Patients' views on the utility of quality of life questionnaires in head and neck cancer: a randomised trial. Clinical Otolaryngology. 2006;31(4):310–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-4486.2006.01256.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chang V, et al. The Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale short form. Cancer. 2000;89:1162–1171. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20000901)89:5<1162::aid-cncr26>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Portenoy RK, et al. The Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale: An instrument for the evaluation of symptom prevalence, characteristics and distress. European Journal of Cancer. 1994;30A(9):1326–1336. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(94)90182-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tranmer JE, et al. Measuring the symptom experience of seriously ill cancer and noncancer hospitalized patients near the end of life with the Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale. Journal of Pain & Symptom Management. 2003;25(5):420–9. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(03)00074-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chang VT, et al. Symptom and quality of life survey of medical oncology patients at a veterans affairs medical center: a role for symptom assessment. Cancer. 2000;88(5):1175–83. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(20000301)88:5<1175::aid-cncr30>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nelson JF, et al. The symptom burden of chronic critical illness. Critical Care Medicine. 2004;32(7):1527–1534. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000129485.08835.5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Harrison LB, et al. Detailed quality of life assessment in patients treated with primary radiotherapy for squamous cell cancer of the base of the tongue. Head & Neck. 1997;19(3):169–75. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0347(199705)19:3<169::aid-hed1>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sandberg J, et al. A qualitative study of the experiences and satisfaction of direct telemedicine providers in diabetes case management. Telemedicine and e-Health. 2009;15(8):742–750. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2009.0027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]