Abstract

Allergies and asthma are diseases that affect individuals of all ages, and their prevalence is comparable in all age groups. As age demographics in the United States and other countries shift to greater proportions and numbers of patients in the “elderly” categories, it is becoming increasingly important for clinicians to become aware of the impact of aging on a variety of diseases. Allergy and asthma are recognized as inflammatory disorders, and there are data that demonstrate that age-related changes in immune function can have a significant impact these disorders.

Introduction

Although allergies and asthma are often thought of as childhood disorders, the symptoms and clinical disorders often persist into older age and can occasionally make their initial appearance in the elderly. Asthma is a clinical diagnosis that is characterized by airway inflammation in association with reversible airflow obstruction and bronchial hyperresponsiveness, and it has an estimated prevalence of 8–10% across all age groups1. This chapter will examine the available data regarding the interplay of the aging process with allergic disease and asthma and discuss the diagnosis and management of asthma in older patients.

Allergic Responses in the Elderly

It is common to hear of individuals “growing out” of their allergies, suggesting that typical nasal and ocular symptoms upon exposure to allergens can diminish with age. Several studies have demonstrated age-related declines in serum total IgE, and serum total IgE comparisons between younger and older subjects without any allergic disease have demonstrated significantly lower levels in the older subjects2. In a study of 326 subjects with allergic disease (asthma, allergic rhinitis, atopic dermatitis or chronic urticaria), it was noted that both age and sex affected total serum IgE levels, with peak levels attained in the 2nd and 3rd decades of life followed by a progressive decline that was more pronounced in women3. In a population-based study of longitudinal change in total IgE levels, a decrease in IgE was observed over an eight-year span regardless of the starting age (>20 years old)4. There is also evidence for a corresponding age-related decline in the total number of allergen sensitivities5.

Given these changes in allergic inflammation with aging, one might conclude that allergic rhinitis and asthma in the elderly should be milder or become nonexistent. However, the relationship between total IgE and allergic disease persists in the elderly, such that subjects with relatively higher total IgE levels remain more likely to have allergic rhinitis or asthma6;7. Furthermore, there is a suggestion that sensitivity to particular allergens such as the indoor allergens, dust mite and cockroach, are more prominently associated with the presence of asthma in an elderly population7;8.

Though allergic inflammation persists and is perhaps attenuated as one ages, there are also numerous non-allergen triggers that are commonly associated with rhinitis symptoms and exacerbations of asthma. These include irritants (e.g. noxious smells and cold air) and respiratory infections, and these triggers may be associated with inflammatory features that are similar to those that occur with allergen exposure.

Epidemiology of Bronchial Hyperreactivity and Asthma

With current demographic trends in the United States, the number of elderly individuals with asthma will double within the next 20 years9. While mortality from asthma is decreasing in most age groups, the mortality in the elderly has remained constant10, with the exception of an increase in elderly African-American women11. Identifying the differences seen in asthma in the growing elderly population will be important in diagnosing the disease, improving its morbidity and mortality, and in determining optimal therapies. The TENOR study examined the natural history of allergic disease in a cohort of older (> 65 years old) subjects relative to their younger counterparts and found that older asthmatics had lower total IgE levels, fewer positive skin-prick tests, and less concomitant allergic rhinitis or atopic dermatitis12.

In an analysis of NHANES III data, it was found that 6.8% of the overall population had objective evidence of low lung function (FEV1) on spirometry that could represent asthma, COPD or a combination of the two13. An additional 7.2% of the population may represent individuals with undiagnosed asthma or COPD; they exhibited an FEV1 to FVC ratio less than 0.7 and an FEV1 greater than 80% of predicted, with age greater than 85 being a significant predictor for being in this group. Indeed, these statistics suggest that obstructive airway disease is under-diagnosed in the elderly population. A similar finding was reported in a cardiovascular health study; 4% of subjects greater than 65 years of age had a diagnosis of asthma, and an additional 4% had symptoms consistent with probable asthma14.

Additional data suggest that advancing age, irrespective of any concomitant pulmonary disease, is associated with increased bronchial hyperresponsiveness. In a study of 148 subjects ranging from age 5 to 76 years, age had an independent association with bronchial hyperresponsiveness as measured by a methacholine challenge15. In another study, bronchial hyperresponsiveness to histamine challenge was associated with increased eosinophil counts and allergic sensitization; however, older age also maintained an independent association with the bronchial hyperresponsiveness, which was more prominent in subjects with respiratory symptoms16. It is recognized that smoking and the baseline FEV1, in addition to age, are also strong influences on bronchial hyperresponsiveness17;18.

Contrast with COPD

Distinguishing between asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) frequently becomes an issue when airway obstruction is evaluated in the elderly. In a study focusing on the lung function and inflammatory differences between asthma and COPD, it was observed that in the asthma subjects there had significantly more allergic sensitivity, higher values for DLCO, greater increases in FEV1 following bronchodilator or corticosteroids, and more eosinophils in peripheral blood, bronchoalveolar lavage and sputum19. However, it is also likely that an overlap syndrome exists for some patients in which features of asthma and COPD are both present, but this subset of patients has yet to be carefully examined and is typically excluded from investigational studies.

The “Dutch Hypothesis” is an interesting view of asthma and COPD that proposes there is one common obstructive lung disease that includes both asthma and COPD (for review20). This hypothesis suggests that is a common genetic predisposition for obstructive lung disease exists and that asthma and COPD differ with respect to the lung exposures (allergen versus tobacco smoke) that trigger and drives the disorder towards airway obstruction. However, this hypothesis remains controversial because it cannot fully explain some of differences observed between asthma and COPD (for review21).

Lung Function Decline in Asthma

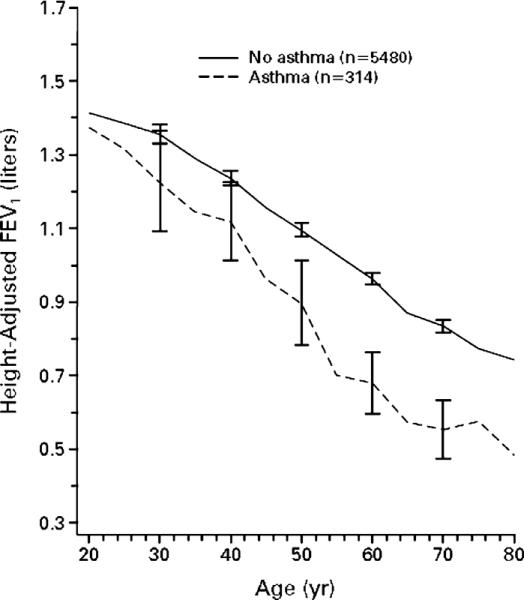

Although it is recognized that aging is associated with a progressive decline in lung function, specifically decreases in the forced expiratory volume in 1 second as well as the forced vital capacity and FEV1/FVC ratio, there are data to suggest that individuals with asthma have more severe decline in lung function over time (Figure 1)22. The reason for this accelerated decline has not been established, but it is commonly attributed to the airway inflammation and airway remodeling that occur with asthma. There is also controversy regarding whether aggressive management of asthma can prevent this accelerated decline. In a recent study of recently diagnosed asthmatics, it was shown that using budesonide treatment for a three year span could reduce the rate of lung function decline by approximately one-third23. Thus, optimal management of asthma throughout life may be required to maintain optimal lung function, reduce morbidity, and prevent early mortality.

Figure 1.

Lung Function Decline with Aging in Asthma

The graph shows the adjusted FEV1 versus age for healthy normals (solid line) and asthma subjects (dashed line). Adapted from Lange et al., NEJM 339: 1194-1200, copyright ©1998 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

Inflammation in Asthma

The inflammation that is typically found in asthma has an allergic profile and consists of predominantly Th2 lymphocytes and mediators (IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13). Studies of sputum samples, bronchoalveolar fluid, and bronchial biopsies have shown baseline inflammation that consists of T-cells and eosinophils with a subsequent influx of additional inflammatory cells including more eosinophils, neutrophils, and lymphocytes into the airway during an exacerbation of asthma24. In addition to these cells, the expression of a number of inflammatory mediators including cytokines, chemokines, and lipids (prostaglandins and leukotrienes) are significantly increased in the airway. Many of these mediators, such as IL-13 and leukotriene LTC4, can directly induce the pathophysiological hallmarks of asthma, including airway hyperresponsiveness, goblet cell hyperplasia, mucus secretion, and smooth muscle cell hypertrophy25;26.

Late-onset asthma is typically non-allergic in nature, and is referred to as “intrinsic” asthma27. It is recognized as a more severe asthma phenotype with a greater degree of airflow obstruction, more frequent exacerbations, and a greater rate of lung function decline. However, the inflammation associated with intrinsic asthma is remarkably similar to extrinsic or allergic asthma, with prominent T-cell and eosinophil involvement28;29. In a study comparing older asthma subjects (greater than 70 years) with either early or late onset of asthma, it was found that early onset of disease was associated with significantly lower pre- and post-bronchodilator percent predicted FEV1 and FEF25-7530.

An important “trigger” of asthma exacerbations is upper respiratory tract viral infection. Estimates suggest that up to 80% of asthma exacerbations in adults are caused by viral upper respiratory infections31. Because immune function is important for the resolution of respiratory infections, question arise regarding the impact of immunosenescence on the clinical features of asthma in the elderly and the resolution of inflammation induced by viral infection. For example, are exacerbations more frequent or severe in the elderly due to an increased susceptibility to viral infection, or does a defect in resolving infection lead to the persistence of viral infections and virus-induced inflammation?

Immunosenescence

Numerous studies suggest that immune function declines with aging, a phenomenon frequently referred to as “immunosenescence”. This is thought to contribute to more frequent infections32, an increased incidence of autoimmune disease33, and increased incidence of malignancy due to impaired immune surveillance34. Immunosenescence has been described for both adaptive and innate components of the immune response.

The most extensively studied component of the immune system with regards to immunosenescence is the T-cell population. The involution of the thymus gland begins shortly after birth and undergoes replacement by fatty tissue that is nearly complete by 60 years of age. Consequently, a decline in the numbers of circulating naïve T-cells gradually occurs, and memory T-cells (CD45RO+) eventually predominate35. Additionally, the T-cell receptor repertoire diversity appears to diminish, and T helper cell activity declines36. Other observations of the T-cell population with aging include reduced proliferative responses37, a decrease in CD8+ T cell levels38, a shift of Th1 to Th2 cytokine profiles upon stimulation with PMA (phorbol myristic acid)39, a decline in Fas-mediated T-cell apoptosis40, and increased DR expression on T-cells41. In addition, an increased proportion of FOXP3+ CD4+ T regulatory cells with intact suppressive capabilities have been found in peripheral blood from elderly subjects, which may help explain the decreased T-cell functional activities described above42. Whether any of these age-related changes is more or less pronounced in specific inflammatory disorders, such as allergic diseases or asthma, is not known.

A decreased production of B-cells with aging has been observed in mice, and this is likely to be true for humans as well43;44. More specifically, there is a transition from the presence of naïve B-cells to “antigen-experienced” B-cells45. In mice, the ability to produce antibody remains intact with aging46; however, the quality of antibody produced is altered with lower affinity and avidity for antigen47. This observation is likely due to deficient somatic hypermutation, which is responsible for enhancement of antibody specificity for antigen48.

The ability of neutrophils to kill phagocytosed organisms is diminished in the elderly as compared to younger individuals49. This is possibly due to a decrease in the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS)50;51. In addition, it has been observed that neutrophils in the elderly undergo apoptosis more easily, possibly due to deficient cytokine pro-survival signaling pathways to protect the neutrophils52;53. Therefore, neutrophils may be less abundant in acute inflammatory responses due to an increased tendency to undergo apoptosis, and those present may have diminished anti-pathogen activity, which may increase susceptibility to more frequent and more severe respiratory infections. Of note, many other neutrophil functions are unchanged with aging such as adhesion, migration into inflammatory tissue, and phagocytosis.

The presence of eosinophils in the asthmatic airway has been shown to be a marker for disease activity, and its decrease with therapies has served as a predictor of clinical responsiveness54;55. In a study examining age-related changes in eosinophil function, it was found that peripheral blood eosinophils from older asthma subjects exhibited decreased degranulation in response to cytokine stimulation and displayed a trend for decreased superoxide production56. Thus, eosinophils may have an altered or diminished role in the airway inflammation of older asthma patients.

NK cells are cytotoxic cells that play an important role in anti-viral host defense. Although the numbers of NK cells increase with aging, the cytotoxicity of NK cells diminishes with advancing age57;58. In contrast, NKT cells, a subset of NK cells, have been shown to decrease in elderly subjects59.

Whether the increased susceptibility to infectious disease associated with immunosenescence contributes to the pathogenesis and/or severity of asthma in the elderly has yet to be determined. Respiratory pathogens such as Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Chlamydia pneumoniae, and rhinovirus (RV) may contribute to asthma severity60;61. Because a majority of asthma exacerbations are triggered by viral upper respiratory infections, age-related changes in anti-viral responses may have significant consequences for morbidity and mortality.

Interestingly, very old individuals with less evidence of immunosenescent changes and fairly well-preserved immune responses are more likely to have prolonged survival62. Conversely, decreased survival was associated with features of immunosenescence that included impaired T-cell proliferative responses to mitogenic stimulation, increased numbers of CD8+ cytotoxic/suppressor cells, and low numbers of CD4+ T-cells and CD19+ B-cells63.

Another component of immunosenescence is the presence of a chronic systemic inflammation, often referred to as “inflamm-aging”, which is characterized by increased serum IL-6 and TNF-α64. Inflamm-aging is typically associated with more “frail” individuals and the precise etiology of the increased serum IL-6 and TNF-α is not known. However, chronically elevated levels of these cytokines in the elderly may certainly contribute to organ-specific or systemic inflammatory processes, including asthma.

Immunosenescence and Airway Inflammation in Asthma

The aging process has been shown to be associated with changes in lung inflammation without concomitant lung disease. An examination of the cellular composition of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) from subjects ranging in age from 19 to 83 year and lacking a history of allergies, pulmonary disease or gastroesophageal reflux, showed an increase in BALF neutrophils and CD4+ T-cells65;66. Furthermore, the T-cells also appeared to be more activated in the elderly with increased expression of HLA-DR and CD69. This increase in airway neutrophils has also been observed in asthma subjects56. Furthermore, the increased airway neutrophilia corresponds to increased levels of neutrophil mediators in older asthma subjects, which resembles the changes seen neutrophil-predominant severe asthma (in press)67. Thus, it is unclear whether the increased airspace neutrophils contribute to greater severity of asthma in the elderly.

In the Normative Aging Study, a large cohort of subjects, ages 21–80 years without any chronic diseases including asthma at the time of enrollment were followed. In a study of case-controlled subsets of subjects from this study (mean age 61 years), it was shown that allergic sensitization to cat was a predictor for the subsequent development of airway hyperresponsiveness or asthma68. Further analyses of this cohort found asthma in the elderly to be associated with increased allergic sensitization to cockroach8 and dust mite7. In addition, chronic respiratory symptoms and airway hyperresponsiveness were associated with elevated eosinophil counts in the peripheral blood6. Thus, these studies have identified risk factors for asthma in older subjects, such as allergic sensitization, total IgE and elevated eosinophil counts, which are also considered risk factors for asthma in younger subjects.

One of the recent tools that can provide a noninvasive assessment of airway inflammation is the measurement of exhaled nitric oxide (NO). In a study examining 2200 subjects, 25–75 years of age, it was found that an increase in exhaled NO was associated with advancing age69. This increase may be reflective of the altered distribution of inflammatory cells or altered activity of inflammatory cells in the airway. In either case, this demonstrates another important and perhaps clinically relevant difference between younger and older asthma subjects.

The airway inflammation of older asthma subjects has been examined in two contexts: to establish whether age-related changes are present and to establish differences between asthma and COPD. Older asthma subjects with evidence of atopy continue to exhibit airway eosinophil levels comparable to younger asthma subjects56. In asthmatics, the most notable difference in the airway cellular distribution with aging is an increase in neutrophils with a corresponding decrease in macrophages, which is also seen in older individuals without asthma56;65;70. In a study comparing older asthma subjects with fixed airway obstruction and COPD subjects, the asthma subjects had significantly elevated blood and sputum eosinophils and eosinophilic cationic protein (ECP) levels71.

Diagnosis of Asthma in the Elderly

A definitive diagnostic test for asthma does not exist. Rather, the diagnosis of asthma is based on a constellation of symptoms, the patient's personal and family history, physical examination findings, and supportive pulmonary function tests. Asthma symptoms typically include any combination of wheezing, dyspnea, or cough. Although these features are non-specific and found in many pulmonary diseases, the patient often relates recurrent, intermittent episodes of these symptoms. There are often specific allergic or non-allergic triggers of these symptoms such as exposures to pollens, molds, dust mites, cockroach, tobacco smoke, weather changes, cold air, aspirin/NSAID use, aerosolized irritants or exercise. Another common trigger for many asthma patients is a viral upper respiratory infection (URI) that can lead to an asthma exacerbation and an increase in asthma symptoms that persists for weeks.

In older patients, there are additional disorders to consider in the differential diagnosis of asthma (as noted in Table 1). COPD typically has symptoms similar to asthma but is almost always associated with a long-standing history of tobacco smoking. There are guidelines, (summarized in Table 2) that can help identify distinguishing features of asthma, which include the presence of other allergic symptoms, bronchodilator reversibility, and the presence of eosinophilia72. Vocal cord dysfunction (VCD), which is an inappropriate closure of the vocal cords during inspiration and/or expiration, can occur alone or as a coexisting condition with asthma. The pulmonary congestion from congestive heart failure (CHF) can present with symptoms similar to asthma, and symptoms are typically worse at night and more intense with physical activity. However, CHF often has additional findings such as pleural effusions, lower extremity edema, and an abnormal cardiac examination. Mechanical obstruction of the airway from a tumor mass or foreign body can mimic the obstruction of asthma. However, systemic manifestations or radiographic findings will often suggest this possibility as the cause of symptoms.

Table 1.

Differential Diagnosis in Asthma

| Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) |

| Vocal Cord Dysfunction (VCD) |

| Congestive Heart Failure (CHF) |

| Mechanical obstruction of airways (e.g. tumors) |

Table 2.

Distinguishing Features of Asthma and COPD

| Characteristic | Asthma | COPD |

|---|---|---|

| History | ||

| Episodic Wheeze | Common | Less common |

| Nocturnal dyspnea or cough | Common | Not common |

| Other allergic symptoms | Frequent | infrequent |

| Smoking history | Less common | Almost always |

| Laboratory Findings | ||

| Chest X-ray | Often normal | Emphysema- hyperaeration; Chronic bronchitis- increased markings |

| Eosinophilia | More common | Less common |

| Total serum IgE | Usually elevated | Elevation less common |

| Response to Therapy | ||

| β2-agonist | Increased FEV1 with symptom relief | Little/no change in FEV1 and poor symptom relief |

Management of Asthma in the Elderly

The goal of asthma therapy is to reduce the frequency and severity of both symptoms and exacerbations, maintain normal levels of activity, and achieve optimal lung function. There are two aspects of asthma therapy that must be addressed: baseline controller therapy and a plan for modification of therapeutic regimen based on changes in asthma control, which is often referred to as an “asthma action plan”.

The latest NIH guidelines for the management of asthma include a brief section on asthma in the elderly. The recommended treatment is no different than for younger adults with the acknowledgment that anticholinergics may have a greater role. However, the guideline points out that treating clinicians should be wary of potential side effects and be aware of medications used for treatment of comorbidities that could impact asthma such as beta-blockers.

There are a number of challenges in the management of asthma in the elderly. Older patients have a poor perception of their asthma symptoms when compared to their younger counterparts, and this tolerance and suppressed recognition of symptoms may contribute to increased morbidity in elderly patients73;74. Older patients have increased difficulty utilizing prescribed medication effectively due to mechanical difficulties in using the inhaler devices.

Older asthma subjects (>55 or >65 years old) are typically excluded from investigational studies on pharmacological therapies of asthma due to their frequent, inherent comorbidities and the need to simplify clinical trials. Thus, the evidence base for treatment of asthma in older patients is not well established. There are two reports on the use asthma treatments in an older population, using zafirlukast and omalizumab75;76. Both of these studies showed clinical benefit, but interestingly, the criteria for efficacy differed from their younger counterparts. This raises the question of whether asthma evolves into a phenotypically different disease with aging. Furthermore, given the roles of immune cells in asthma, there are several mechanisms by which immunosenescence could affect asthma: 1) baseline airway inflammation may be altered, 2) airway inflammatory responses to an allergen trigger may be altered, and/or 3) airway inflammatory responses to a respiratory pathogen may be altered. In fact, it is quite likely that immunosenescence affects all three of these aspects of immune function in asthma. Thus, the clinical consequences of these effects are likely to be an important consideration for management of asthma in the elderly.

There are several co-morbidities that can complicate asthma management, including gastroesophageal reflux disease, allergic rhinitis, chronic rhinosinusitis, and VCD. It is often difficult to gain optimal control of asthma symptoms unless these co-existing disorders have also been treated. Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a common disorder in patients with asthma with one study finding symptoms of heartburn in 77% of asthmatic patients compared to 50% of the control group77.

Allergic rhinitis and chronic rhinosinusitis are conditions that commonly co-exist with asthma and may inhibit or worsen asthma control. A common inflammatory pathway with communication between the nose and lung has been suggested78, and support for this relationship was provided in a study in which patients with seasonal allergic rhinitis and asthma were given antigen in the nose and subsequently developed increased lower airway hyperresponsiveness as measured by a change in methacholine PC2079. In a followup study, patients with allergic rhinitis and asthma were treated with intranasal corticosteroids or placebo during ragweed season. Although FEV1, peak flows, and symptoms were not significantly different in the two groups, airway hyperresponsiveness decreased in the treatment group80.

Patients with chronic rhinosinusitis exhibit a chronic inflammatory process in the sinuses with features that are similar to the lower airway inflammation in asthma81;82. Surgical treatment of chronic rhinosinusitis has been reported to improve asthma control in adults, although a concern of this study was the lack of a control group that had not received surgery83. Nonetheless, the treatment of allergic rhinitis and chronic rhinosinusitis with either intranasal medications or endoscopic sinus surgery may contribute significantly to asthma control.

VCD can cause upper airway obstruction with symptoms that mimic asthma, and it can occasionally occur in patients who actually have asthma. The diagnosis of VCD is suggested by the sudden onset and resolution of symptoms, an attenuated or lack of response to standard asthma therapy, and symptoms that “localized” to the vocal cords, e.g. hoarseness and proximal, monophonic wheezing on auscultation. A definitive diagnosis of VCD can be established by visualization of the vocal cords and observation of the paradoxical vocal cord movement; however, in the absence of active symptoms, this may not occur due to its episodic nature. Another characteristic of VCD is the demonstration of a “cutoff” on the inspiratory portion of the flow-volume loop, which represents the extrathoracic obstruction from a complete or partial paradoxical closure of the vocal cords during inspiration. This inspiratory cutoff may not be present in the absence of symptoms.

As mentioned above, it is common for asthma and VCD to co-exist, and up to 50% of patients with a diagnosis of VCD also had airway hyperresponsiveness84. Moreover, for unclear reasons, VCD occurs more commonly in women85. Interestingly, other co-morbities for asthma are also associated with VCD including rhinitis and GERD. Thus, rhinitis and GERD should be treated to minimize their contribution to irritation of the vocal cords. Referral to speech therapy for instruction on breathing exercises during direct visualization of the vocal cords can also be effective in managing symptoms86.

Summary

Allergies and asthma affect individuals in all age groups, but are often unrecognized or undertreated in the elderly. Allergies and asthma are inflammatory disorders, and there is a growing body of literature describing age-related changes in immune function. Our current state of knowledge provides some insight into specific age-related changes in the function of inflammatory cells or their levels. However, the clinical consequences of these age-related changes with respect to the diagnosis or management of asthma are not fully appreciated. There are data, as discussed in this chapter, indicating that asthma in the elderly is not the same as in younger subjects. Therefore, in order to better serve the health care needs of our aging population, more research is required to define the airway immune functional changes in individuals with asthma. Furthermore, recruitment of older subjects into asthma clinical trials is necessary to provide an evidence-base for efficacy of available therapeutics as well as those in development.

Reference List

- (1).NAEPP . NIH Publication No. 07-4051. National Institutes of Health: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; Aug 28, 2007. Expert Panel Report 3: Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma. [Google Scholar]

- (2).Delespesse G, De Maubeuge J, Kennes B, et al. IgE Mediated Hypersensitivity in Aging. Clinical Allergy. 1977;7(2):155–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.1977.tb01436.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Hanneuse Y, Delespesse G, Hudson D, et al. Influence of Aging on IgE-Mediated Reactions in Allergic Patients. Clinical Allergy. 1978;8(2):165–174. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.1978.tb00461.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Jarvis D, Luczynska C, Chinn S, et al. Change in prevalence of IgE sensitization and mean total IgE with age and cohort. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2005;116(3):675–682. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Barbee RA, Kaltenborn W, Lebowitz MD, et al. Longitudinal Changes in Allergen Skin-Test Reactivity in A Community Population-Sample. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 1987;79(1):16–24. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(87)80010-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Annema JT, Sparrow D, OConnor GT, et al. Chronic Respiratory Symptoms and Airway Responsiveness to Methacholine Are Associated with Eosinophilia in Older Men - the Normative Aging Study. Eur Respir J. 1995;8(1):62–69. doi: 10.1183/09031936.95.08010062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).King MJ, Bukantz SC, Phillips S, et al. Serum total IgE and specific IgE to Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus, but not eosinophil cationic protein, are more likely to be elevated in elderly asthmatic patients. Allergy & Asthma Proceedings. 2004;25(5):321–325. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Rogers L, Cassino C, Berger KI, et al. Asthma in the elderly - Cockroach sensitization and severity of airway obstruction in elderly nonsmokers. Chest. 2002;122(5):1580–1586. doi: 10.1378/chest.122.5.1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Slavin RG. Asthma in the Elderly. Respiratory Digest. 2006;8(2):3–11. [Google Scholar]

- (10).Moorman JE, Rudd RA, Johnson CA, et al. National Surveillance for Asthma- United States, 1980–2004. MMWR Surveillance Summaries. 2007;56(SS08):1–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Moorman JE, Mannino DM. Increasing US asthma mortality rates: Who is really dying? Journal of Asthma. 2001;38(1):65–71. doi: 10.1081/jas-100000023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Slavin RG, Haselkorn T, Lee JH, et al. Asthma in older adults: observations from the Epidemiology and Natural History of Asthma: Outcomes and treatment regimens (TENOR) study. Annals of Allergy Asthma & Immunology. 2006;96(3):406–414. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60907-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Mannino DM, Gagnon RC, Petty TL, et al. Obstructive lung disease and low lung function in adults in the United States - Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1994. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2000;160(11):1683–1689. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.11.1683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Enright PL, McClelland RL, Newman AB, et al. Underdiagnosis and undertreatment of asthma in the elderly. Chest. 1999;116(3):603–613. doi: 10.1378/chest.116.3.603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Hopp RJ, Bewtra A, Nair NM, et al. The effect of age on methacholine response. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 1985;76(4):609–613. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(85)90783-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Rijcken B, Schouten JP, Mensinga TT, et al. Factors Associated with Bronchial Responsiveness to Histamine in A Population-Sample of Adults. American Review of Respiratory Disease. 1993;147(6):1447–1453. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/147.6_Pt_1.1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Burney PGJ, Britton JR, Chinn S, et al. Descriptive Epidemiology of Bronchial Reactivity in An Adult-Population - Results from A Community Study. Thorax. 1987;42(1):38–44. doi: 10.1136/thx.42.1.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Paoletti P, Carrozzi L, Viegi G, et al. Distribution of Bronchial Responsiveness in A General-Population - Effect of Sex, Age, Smoking, and Level of Pulmonary-Function. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;151(6):1770–1777. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.151.6.7767519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Fabbri LM, Romagnoli M, Corbetta L, et al. Differences in airway inflammation in patients with fixed airflow obstruction due to asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167(3):418–424. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200203-183OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Kraft M. Asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exhibit common origins in any country! Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174(3):238–240. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2604007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Barnes PJ. Against the Dutch hypothesis: Asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease are distinct diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174(3):240–243. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2604008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Lange P, Parner J, Vestbo J, et al. A 15-year follow-up study of ventilatory function in adults with asthma. New England Journal of Medicine. 1998;339(17):1194–1200. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199810223391703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).O'Byrne PM, Pedersen S, Busse WW, et al. Effects of early intervention with inhaled budesonide on lung function in newly diagnosed asthma. Chest. 2006;129(6):1478–1485. doi: 10.1378/chest.129.6.1478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Metzger WJ, Zavala D, Richerson HB, et al. Local Allergen Challenge and Bronchoalveolar Lavage of Allergic Asthmatic Lungs - Description of the Model and Local Airway Inflammation. American Review of Respiratory Disease. 1987;135(2):433–440. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1987.135.2.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Wills-Karp M. Interleukin-13 in asthma pathogenesis. Immunological Reviews. 2004;202:175–190. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.00215.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Busse W, Kraft M. Cysteinyl leukotrienes in allergic inflammation - Strategic target for therapy. Chest. 2005;127(4):1312–1326. doi: 10.1378/chest.127.4.1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Reed CE. The natural history of asthma. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2006;118(3):543–548. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Bentley AM, Menz G, Storz C, et al. Identification of Lymphocytes-T, Macrophages, and Activated Eosinophils in the Bronchial-Mucosa in Intrinsic Asthma - Relationship to Symptoms and Bronchial Responsiveness. American Review of Respiratory Disease. 1992;146(2):500–506. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/146.2.500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Bentley AM, Durham SR, Kay AB. Comparison of the Immunopathology of Extrinsic, Intrinsic and Occupational Asthma. Journal of Investigational Allergology & Clinical Immunology. 1994;4(5):222–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Braman SS, Kaemmerlen JT, Davis SM. Asthma in the Elderly - A Comparison Between Patients with Recently Acquired and Long-Standing Disease. American Review of Respiratory Disease. 1991;143(2):336–340. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/143.2.336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Nicholson KG, Kent J, Ireland DC. Respiratory Viruses and Exacerbations of Asthma in Adults. British Medical Journal. 1993;307(6910):982–986. doi: 10.1136/bmj.307.6910.982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Castle SC, Uyemura K, Fulop T, et al. Host Resistance and Immune Responses in Advanced Age. Clinics in Geriatric Medicine. 2007;23(3):463–479. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2007.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Boren E, Gershwin ME. Inflamm-aging: autoimmunity, and the immune-risk phenotype. Autoimmunity Reviews. 2004;3(5):401–406. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2004.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Derhovanessian E, Solana R, Larbi A, et al. Immunity, ageing and cancer. Immunity & Ageing. 2008;5(1):11–26. doi: 10.1186/1742-4933-5-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Flurkey K, Stadecker M, Miller RA. Memory T lymphocyte hyporesponsiveness to noncognate stimuli: a key factor in age-related immunodeficiency. Eur J Immunol. 1992;22(4):931–935. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830220408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Naylor K, Li G, Vallejo AN, et al. The influence of age on T cell generation and TCR diversity. J Immunol. 2005;174(11):7446–7452. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.11.7446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Swain S, Clise-Dwyer K, Haynes L. Homeostasis and the age-associated defect of CD4 T cells. Semin Immunol. 2005;17(5):370–377. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2005.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Cakman I, Rohwer J, Schutz RM, et al. Dysregulation between TH1 and TH2 T cell subpopulations in the elderly. Mechanisms of Ageing and Development. 1996;87(3):197–209. doi: 10.1016/0047-6374(96)01708-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Sandmand M, Bruunsgaard H, Kemp K, et al. Is ageing associated with a shift in the balance between Type 1 and Type 2 cytokines in humans? Clinical and Experimental Immunology. 2002;127(1):107–114. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2002.01736.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Zhou T, Edwards CK, III, Mountz JD. Prevention of age-related T cell apoptosis defect in CD2-fas-transgenic mice. J Exp Med. 1995;182(1):129–137. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.1.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Jackola DR, Ruger JK, Miller RA. Age-associated changes in human T cell phenotype and function. Aging (Milano ) 1994;6(1):25–34. doi: 10.1007/BF03324210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Lages CS, Suffia I, Velilla PA, et al. Functional Regulatory T Cells Accumulate in Aged Hosts and Promote Chronic Infectious Disease Reactivation. J Immunol. 2008;181(3):1835–1848. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.3.1835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Johnson SA, Cambier JC. Ageing, autoimmunity and arthritis: Senescence of the B cell compartment - implications for humoral immunity. Arthritis Research & Therapy. 2004;6(4):131–139. doi: 10.1186/ar1180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).McKenna RW, Washington LT, Aquino DB, et al. Immunophenotypic analysis of hematogones (B-lymphocyte precursors) in 662 consecutive bone marrow specimens by 4-color flow cytometry. Blood. 2001;98(8):2498–2507. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.8.2498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Johnson SA, Rozzo SJ, Cambier JC. Aging-dependent exclusion of antigen-inexperienced cells from the peripheral B cell repertoire. Journal of Immunology. 2002;168(10):5014–5023. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.10.5014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Dailey RW, Eun SY, Russell CE, et al. B cells of aged mice show decreased expansion in response to antigen, but are normal in effector function. Cellular Immunology. 2001;214(2):99–109. doi: 10.1006/cimm.2001.1894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Doria G, Dagostaro G, Poretti A. Age-Dependent Variations of Antibody Avidity. Immunology. 1978;35(4):601–611. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Miller C, Kelsoe G. Ig V-H Hypermutation Is Absent in the Germinal-Centers of Aged Mice. Journal of Immunology. 1995;155(7):3377–3384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Corberand J, Ngyen F, Laharrague P, et al. Polymorphonuclear Functions and Aging in Humans. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1981;29(9):391–397. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1981.tb02376.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Fu YK, Arkins S, Li YM, et al. Reduction in Superoxide Anion Secretion and Bactericidal Activity of Neutrophils from Aged Rats - Reversal by the Combination of Gamma-Interferon and Growth-Hormone. Infection and Immunity. 1994;62(1):1–8. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.1.1-8.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Tortorella C, Ottolenghi A, Pugliese P, et al. Relationship Between Respiratory Burst and Adhesiveness Capacity in Elderly Polymorphonuclear Cells. Mechanisms of Ageing and Development. 1993;69(1–2):53–63. doi: 10.1016/0047-6374(93)90071-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Fulop T, Fouquet C, Allaire P, et al. Changes in apoptosis of human polymorphonuclear granulocytes with aging. Mechanisms of Ageing and Development. 1997;96(1–3):15–34. doi: 10.1016/s0047-6374(96)01881-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Tortorella C, Piazzolla G, Spaccavento F, et al. Spontaneous and fas-induced apoptotic cell death in aged neutrophils. Journal of Clinical Immunology. 1998;18(5):321–329. doi: 10.1023/a:1023286831246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Green RH, Brightling CE, McKenna S, et al. Asthma exacerbations and sputum eosinophil counts: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;360(9347):1715–1721. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11679-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Spahn JD. Asthma biomarkers in sputum. Immunology and Allergy Clinics of North America. 2007;27(4):607–622. doi: 10.1016/j.iac.2007.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Mathur SK, Schwantes EA, Jarjour NN, et al. Age-related changes in eosinophil function in human subjects. Chest. 2008;133(2):412–419. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-2114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Facchini A, Mariani E, Mariani AR, et al. Increased Number of Circulating Leu 11+ (Cd 16) Large Antigranulocytes Lymphocytes and Decreased Nk Activity During Human Aging. Clinical and Experimental Immunology. 1987;68(2):340–347. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Miyaji C, Watanabe H, Toma H, et al. Functional alteration of granulocytes, NK cells, and natural killer T cells in centenarians. Human Immunology. 2000;61(9):908–916. doi: 10.1016/s0198-8859(00)00153-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).DelaRosa O, Tarazona R, Casado JG, et al. V alpha 24(+) NKT cells are decreased in elderly humans. Experimental Gerontology. 2002;37(2–3):213–217. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(01)00186-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Kraft M, Cassell GH, Henson JE, et al. Detection of Mycoplasma pneumoniae in the airways of adults with chronic asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;158(3):998–1001. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.158.3.9711092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Holgate ST. Rhinoviruses in the pathogenesis of asthma: The bronchial epithelium as a major disease target. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2006;118(3):587–590. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).Franceschi C, Monti D, Sansoni P, et al. The immunology of exceptional individuals: the lesson of centenarians. Immunol Today. 1995;16(1):12–16. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(95)80064-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (63).Ferguson FG, Wikby A, Maxson P, et al. Immune parameters in a longitudinal study of a very old population of Swedish people: a comparison between survivors and nonsurvivors. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1995;50(6):B378–B382. doi: 10.1093/gerona/50a.6.b378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (64).Franceschi C, Capri M, Monti D, et al. Inflammaging and anti-inflammaging: A systemic perspective on aging and longevity emerged from studies in humans. Mechanisms of Ageing and Development. 2007;128(1):92–105. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2006.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (65).Meyer KC, Rosenthal NS, Soergel P, et al. Neutrophils and low-grade inflammation in the seemingly normal aging human lung. Mechanisms of Ageing and Development. 1998;104(2):169–181. doi: 10.1016/s0047-6374(98)00065-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (66).Meyer KC, Soergel P. Variation of bronchoalveolar lymphocyte phenotypes with age in the physiologically normal human lung. Thorax. 1999;54(8):697–700. doi: 10.1136/thx.54.8.697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (67).Wenzel SE. Asthma: defining of the persistent adult phenotypes. Lancet. 2006;368(9537):804–813. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69290-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (68).Litonjua AA, Sparrow D, Weiss ST, et al. Sensitization to Cat Allergen Is Associated with Asthma in Older Men and Predicts New-onset Airway Hyperresponsiveness . The Normative Aging Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;156(1):23–27. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.156.1.9608072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (69).Olin AC, Rosengren A, Thelle DS, et al. Height, age, and atopy are associated with fraction of exhaled nitric oxide in a large adult general population sample. Chest. 2006;130(5):1319–1325. doi: 10.1378/chest.130.5.1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (70).Thomas RA, Green RH, Brightling CE, et al. The Influence of Age on Induced Sputum Differential Cell Counts in Normal Subjects. Chest. 2004;126(6):1811–1814. doi: 10.1378/chest.126.6.1811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (71).Di Lorenzo G, Mansueto P, Ditta V, et al. Similarity and differences in elderly patients with fixed airflow obstruction by asthma and by chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respiratory Medicine. 2008;102(2):232–238. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2007.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (72).NAEPP . NIH Publication No. 96-3662. National Institutes of Health: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; 1996. Considerations for Diagnosing and Managing Asthma in the Elderly. [Google Scholar]

- (73).Connolly MJ, Crowley JJ, Charan NB, et al. Reduced Subjective Awareness of Bronchoconstriction Provoked by Methacholine in Elderly Asthmatic and Normal Subjects As Measured on A Simple Awareness Scale. Thorax. 1992;47(6):410–413. doi: 10.1136/thx.47.6.410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (74).Ekici M, Apan A, Ekici A, et al. Perception of bronchoconstriction in elderly asthmatics. Journal of Asthma. 2001;38(8):691–696. doi: 10.1081/jas-100107547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (75).Korenblat PE, Kemp JP, Scherger JE, et al. Effect of age on response to zafirlukast in patients with asthma in the Accolate Clinical Experience and Pharmacoepidemiology Trial (ACCEPT) Annals of Allergy Asthma & Immunology. 2000;84(2):217–225. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)62759-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (76).Maykut RJ, Kianifard F, Geba GP. Response of Older Patients with IgE-Mediated Asthma to Omalizumab: A Pooled Analysis. Journal of Asthma. 2008;45(3):173–181. doi: 10.1080/02770900701247277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (77).Field SK, Underwood M, Brant R, et al. Prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux symptoms in asthma. Chest. 1996;109(2):316–322. doi: 10.1378/chest.109.2.316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (78).Bousquet J, van Cauwenberge P, Khaltaev N. Allergic Rhinitis and its Impact on Asthma (ARIA); Executive Summary of the Workshop Report 7–10 December 1999, Geneva, Switzerland. Allergy. 2002;57(9):841–855. doi: 10.1034/j.1398-9995.2002.23625.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (79).Corren J, Adinoff AD, Irvin CG. Changes in Bronchial Responsiveness Following Nasal Provocation with Allergen. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 1992;89(2):611–618. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(92)90329-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (80).Corren J, Adinoff AD, Buchmeier AD, et al. Nasal Beclomethasone Prevents the Seasonal Increase in Bronchial Responsiveness in Patients with Allergic Rhinitis and Asthma. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 1992;90(2):250–256. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(92)90079-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (81).Harlin SL, Ansel DG, Lane SR, et al. A Clinical and Pathologic-Study of Chronic Sinusitis - the Role of the Eosinophil. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 1988;81(5):867–875. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(88)90944-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (82).Newman LJ, Plattsmills TAE, Phillips CD, et al. Chronic Sinusitis - Relationship of Computed Tomographic Findings to Allergy, Asthma, and Eosinophilia. Jama-Journal of the American Medical Association. 1994;271(5):363–367. doi: 10.1001/jama.271.5.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (83).Nishioka GJ, Cook PR, Davis WE, et al. Functional Endoscopic Sinus Surgery in Patients with Chronic Sinusitis and Asthma. Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 1994;110(6):494–500. doi: 10.1177/019459989411000604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (84).Newman KB, Mason UG, Schmaling KB. Clinical-Features of Vocal Cord Dysfunction. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;152(4):1382–1386. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.152.4.7551399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (85).Newman KB, Mason UG, Schmaling KB. Clinical-Features of Vocal Cord Dysfunction. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;152(4):1382–1386. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.152.4.7551399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (86).Martin RJ, Blager FB, Gay ML, et al. Paradoxic Vocal Cord Motion in Presumed Asthmatics. Seminars in Respiratory Medicine. 1987;8(4):332–337. [Google Scholar]