Abstract

Health services have the functions to define community health problems, to identify unmet needs and survey the resources to meet them, to establish SMART objectives, and to project administrative actions to accomplish the purpose of proposed action programs. For maximum efficacy, health systems should rely on newer approaches of management as management-by-objectives, risk-management, and performance management with full and equal participation from professionals and consumers. The public should be well informed about their needs and what is expected from them to improve their health. Inefficient use of budget allocated to health services should be prevented by tools like performance management and clinical governance. Data processed to information and intelligence is needed to deal with changing disease patterns and to encourage policies that could manage with the complex feedback system of health. e-health solutions should be instituted to increase effectiveness and improve efficiency and informing human resources and populations. Suitable legislations should be introduced including those that ensure coordination between different sectors. Competent workforce should be given the opportunity to receive lifetime appropriate adequate training. External continuous evaluation using appropriate indicators is vital. Actions should be done both inside and outside the health sector to monitor changes and overcome constraints.

Keywords: Health, Services, Crises, Reform, Management, Quality

Introduction

Conceptual framework in healthcare

The design and performance of health systems are now at the centre of the international health agenda. Health systems in different countries even in those with similar levels of income, education, and health expenditure, vary widely in performance and in their ability to attain key health goals [1]. Appropriate policies differ widely across country settings [2]. There is no simple stereotyped formula for the organization of health services and no country has discovered an ideal model. Both the configuration and the application of state authority in the health sector should be realigned so as to achieve desired policy objectives [3]. In the last decades of the 20th century, changes led to propagation of the idea of society-based health care system policy, and to more efficiency and advantages [4]. Current opinions favour a substantial role for the state in the health sector [5, 6]. In fact, in spite of effectiveness, efficiency and competitiveness of market forces in other fields, these factors fail in the health sector due to the existence of other essential components of health services that are not always of concern for private sector. These include entities as equity, information, uncertainty and other inherent characteristics of human behaviour [7, 8]. It is of most importance to determine the role of government in regulating private practice, the public-private interface, and the role of private in public health [5, 9]. Reform and privatization do not mean that governments would clear themselves of their responsibilities towards its citizens.

Neither clinical nor health policy can be comfortably based on opinion alone [10]. Designing a national strategy for healthcare is not the difficult part. It is the implementation of that strategy and making it work that is the most difficult task [11]. Hence, greater conceptual clarity is required before implementation [12]. Some would focus on the technical content of health services (e.g. immunizations or intensive care units) while others would focus on institutional arrangements of the health system (e.g. provider payment mechanisms or social insurance) [1]. Despite lack of a simple stereotyped formula for the organization of health services, there are general principles that should govern health services delivery. Service delivery should be based on disease burden studies derived from morbidity and mortality patterns. The main goals of any health system should include better health, responsiveness to the population's expectations and fair financing. Basic amenities of health services, such as clean waiting rooms or adequate beds and food in hospitals are aspects of care that are often highly valued by the population [1].

There are many differences in the objectives and structure of public health and individualized medical care making them two distinctive components of health services. A third closely related component should be mainly dedicated to education and development. The public component of health services should have an essential broad category package, an example of which is shown in Table 1, [13]. These are population-based efforts that aim at investigating community health threats, promoting healthy life styles, prevention of disease or injury, and ensuring the quality of water, food, air, and other resources necessary for good health. These public health practices are likely to be shaped by the resources available, the ways in which the resources are organized, and the characteristic of the community or market served. To make an impact, practices ought to be applied, and supported by management systems at many organizational levels [14]. Underpinning the entire workings of the system are four key functions that explain variation in performance; stewardship; financing (including revenue collection, fund pooling and purchasing); service provision (for personal and non-personal health services); and resource generation (including personnel, facilities and knowledge) [1].

Table 1.

Essential components of public health services

| - Monitor health status to identify community problems. |

| - Diagnose and investigate health problems and health hazards in the community. |

| - Inform, educate, and empower people about health issues. |

| - Mobilize community partnerships to identify and solve health problems. |

| - Develop policies and plans that support individual and community health efforts. |

| - Enforce laws and regulations that protect health and ensure safety. |

| - Link people to needed personal health services and ensure provision of care. |

| - Ensure a competent public and personal health care workforce. |

| - Evaluate the effectiveness, accessibility, and quality of personal and population based health care. |

| - Research for new insights and innovative solutions to health problems. |

For an organization to become and remain viable in a complex and rapidly changing environment, it must carry certain functions. First, it should provide a product or a service that addresses particular needs in the organization's environment; second, it should ensure that the operational units work together and communicate effectively; and it should support and have control especially with regard to distributing resources, providing training, gathering and distributing information about quality … etc. Fourth function is intelligence where it should forecast future needs, opportunities, and threats. The organization should set a policy with long-term goals and objectives [13].

Changes are needed, but too many changes especially when they are not well prepared for are a great risk. Frequent or poorly planned changes lead to loss of credibility and the cooperation of an important element of change; the service consumers. To facilitate change and make effective improvement in health services, a dedicated, internal change agent is needed. Other components are: clear purpose, benefits and expected results; clear responsibilities assigned; long-term support for staff; and an organizational environment that is open to change [14].

With the increasing role of private practice and medical tourism, public policy should not ignore the need to organize ambulatory care, which is delivered through a poorly explored, largely neglected market of diverse, sometimes competitive providers. It should seek innovative ways of improving the provision of both public and nongovernmental ambulatory services, particularly through better financing, regulation and information. The family physician with a good referral system should play a major role as a backbone of a nation's health system, but in many countries it is facing many difficulties [15, 16].

Stewardship

Stewardship is an important role assigned to the state in running a country's health system [3]. It is the response to the needs of the people with transparency, accountability, trust, ethical behaviour, and good decision-making [3]. It goes beyond the conventional role of mere regulation. It was first introduced in the health sector in the 9th century with the appearance of Hisba in the Islamic state that dealt with the regulation of medical and pharmaceuticals practice. It incorporated also requirements regarding the equitable provision of services and the public interest [17]. It extends the concept of good governance and focuses on outcomes rather than processes. Stewardship involves three key aspects: setting, implementing and monitoring the rules for the health system; assuring a level playing field for all actors in the system (particularly purchasers, providers and patients); and defining strategic directions for the health system as a whole [1]. To deal with these aspects, stewardship can be subdivided into six subfunctions: overall system design, performance assessment, priority setting, intersectoral advocacy, regulation, and consumer protection [1]. Intersectoral advocacy is a component of stewardship that is concerned with the promotion of policies in other social systems that are likely to advance health goals [1].

Decentralization

There is an inherent weakness in centralized, bureaucratic organizations in which politicians at the apex seek to control the behaviour of staff at the peripheral through a combination of central planning and national directives. There are obvious attractions in moving away from the highly centralized approach [7, 8]. Decentralized authority and decision making may yield superior public services because local governing as opposed to state administrative units may be more informed of and responsive to local community needs. Alternatively, centralized provision of at least some of the services may be more effective and efficient because central authorities can coordinate activities across local jurisdictions, thereby addressing any spill-over effects and correcting inequities in resources across communities.

Regulations

Strictly speaking, regulation means setting rules. In the health system there are two main types of regulations: sanitary regulation of goods and services, and health care regulation. The former refers to conventional efforts by sanitary authorities to minimize the health hazards generated by the goods and services throughout the economy, as those associated with foodstuffs. Health care regulation refers to organizations charged with the financial, provision and resource development functions of the health system so as to ensure that services offered by the public or private providers meet minimal standards [1].

Some policies, introduced with the best of intentions, have the opposite effects of those that are desired. Measures taken should thoroughly examine the objective of concern, be appropriate and forecast possible disturbance that could result from unbalancing the system. It should carefully investigate or explore different actions possible and other alternatives and possible negative changes that could occur subsequently. System thinking and system dynamics are two related methodologies for studying and managing complex feedback systems, such as one finds in social systems. They help the decision maker to choose an appropriate course of action by investigating the problem, searching out objectives, finding out alternative solutions, evaluating of the alternatives in terms of cost-effectiveness, re-examining of the objectives if necessary and finding the most cost-effective alternative. They anticipate counterintuitive effects of public health initiatives.

Legislations should not neglect other restructural economic activities and consumption patterns that might undermine proposed actions. It should see health services as a system and actions so that one part could make counteractive changes in other parts of the system if these were not taken into consideration.

Planning and management

Health planning is a process of defining community health problems, identifying unmet needs and surveying the resources to meet them, establishing priority goals that are realistic and feasible and projecting administrative action to accomplish the purpose of the proposed program. Proper planning and management are needed for primary, secondary or tertiary level establishment as well as for public, private or non-profitable organizations [18]. Unless planning is provided, required achievements become more and more difficult by just spontaneous improvement. The situation resembles the case where a skilled football player would not ensure victory if his movements were not goal-oriented.

A number of words drawn from military and sporting terminology are used to describe the end-results of planning such as; objective, target and goal (Table 2). A goal is an ultimate desired state towards which objectives and resources are directed. Neither it is constrained by time or existing resources, nor is necessarily attainable. It is formulated at the highest level and is generally broad. An objective is a precise planned end point of all activities that are either achieved or not. A target often refers to a discrete activity such as the percentage of children immunized or given vitamin A. It permits the concept of degree of achievement. Targets are thus concerned with the factors involved in a problem, whereas objectives are concerned directly with the problem itself. Both are used as useful indicators to monitor progress and assess the effectiveness of proposed projects, programs, and policies in reaching their stated goals. Most goals require that several objectives be met before the goal can be accomplished. Good objectives should be SMART, i.e.; specific, measurable, achievable, realistic and time specific. A program is a sequence of activities designed to implement policies and accomplish objectives. It gives a step-by-step approach to guide the actions necessary to reach a predetermined goal. Programs must be closely integrated with objectives.

Table 2.

Definition of some of the most important terms that are commonly used in planning of health services.

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Strategy | Strategy sets out the basic principles on which actions are based. A strategy may serve as the basis for accelerated action while a broader policy is being developed or revised. |

| Policy | Policy sets out the government's position, and is generally developed over a long time-period while it is cleared with relevant bodies. |

| Goals | A goal is an ultimate desired state towards which objectives and resources are directed. It is neither constrained by time or existing resources, nor is necessarily attainable. It is formulated at the highest level and is generally broad. |

| Objectives | An objective is a precise planned end point of all activities that is either achieved or not achieved. |

| Targets | A target often refers to a discrete activity such as the percentage of children immunized or given vitamin A. It permits the concept of degree of achievement. |

| Programs | A program is a sequence of activities designed to implement policies and accomplish objectives. It gives a step-by-step approach to guide the action necessary to reach a predetermined goal. Programs must be closely integrated with objectives. |

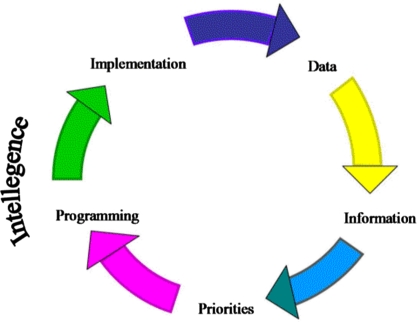

Health planning, which is a continuous cycle. A check on our abilities to achieve our objectives/targets should be undertaken (Figure 1). Our methods to solve the problem might not work, but sometimes priorities also change. It is not only a declaration of intention, but rather a plan with clear goals, objectives, targets, and programs. Intentions or willingness should give their place to plans and evaluation should be expressed in figures.

Figure 1.

The continuous process of health planning cycle

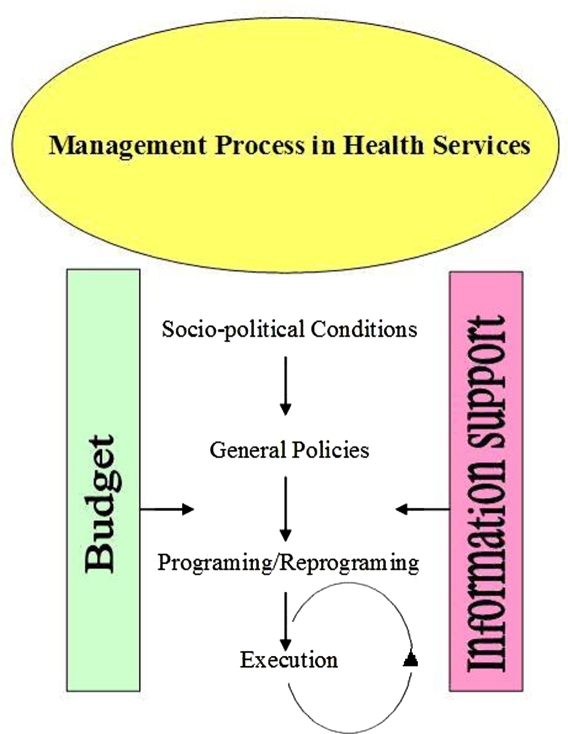

Management is the purposeful and effective use of resources as work force, materials and finances for fulfilling a pre-determined objective (Figure 2). It consists of planning what is to be done, organizing how things are to be done, motivating people to do the work and checking to make sure that the work is progressing satisfactorily. Three terms in management are particularly important to consider. These are: management by objectives, crisis management and risk management. Once priorities are determined, objectives can be stated to overcome the problem. This constitutes the first type of management i.e. management by objectives. Any form of management including performance management that will be discussed should be based on this form. In crisis management, we do nothing, hoping that no problem would occur. If it does, we would face it. The problem is that when a crisis occurs, damages are inevitable. These would include mortality and morbidity, material damage, allocation of human and financial resources, public insatisfaction, loss of confidence in the system, and other intangible losses.

Figure 2.

Management process in Health Services

Risk assessment is a procedure based on the principle that a crisis almost never occurs suddenly without warning signs. There are early signs that have to be considered appropriately at the time. The appearance of a crisis is simulated by the exit of a pen from a gruyere Swiss cheese. It occurs only in the presence of consecutive holes “defects” that permit multiple entry and exit “repeated errors” in the cheese “health system”. These risks should be managed before the occurrence of crisis. Integration of risk assessment with cost analysis and other matters to develop strategies for risk regulation and control is often called risk-management.

Performance management that encloses many of these concepts in management has been one of the success stories of the past decade. It was applied in different economic sectors [12]. The concept is centred around three fundamental goals: improving health, enhancing responsiveness to the expectations of the population, and assuring fairness of financial contribution [1]. It is the process of assessing progress toward achieving predetermined goals and the relevant communication and action on the progress achieved against these predetermined goals [12]. It is a mixture of policy instruments, embracing elements of planning and competition, directives and incentives, and centralization and devolution [7, 8]. Instruments of performance management can be considered under broad headings of guidance, monitoring, and response [12]. It retains some elements of the private market while placing more emphasis on the outcome and accountability of the system by consciously managing it.

Data, information, intelligence and surveillance

Health information is a central tool in health service's planning and administration, research, and training [10, 18]. It is a continuous mechanism for the collection, processing, analysis and transmission of data to provide reliable, relevant, up-to-date, adequate, and reasonably complete information [18]. A high performance information system should be committed to accuracy, appropriateness, completeness, and in-depth analysis [10]. Absence of information results in poor and uninformed decisions, poor planning, poor evaluation and impact assessment with resultant duplicated efforts, less productivity, and waste of time and resources. An information system begins by data that should be provided at periodic intervals. Data consist of discrete observations of attributes or events that carry little meaning when considered alone. This needs to be transformed into information by being reduced, summarized and adjusted for variations in the age and sex composition of the population so that comparisons over time and place are possible. Lastly, it is the transformation of information through integration with experience and perceptions based on social and political values that produces intelligence [18]. Information would have no meaning if necessary actions were not taken to tackle these problems and try to solve them (Figures 1 and 2). Intelligence would reallocate resources to the changing patterns of mortality and morbidity. A health system that is not able to recognize and continuously assess morbidity and mortality patterns of the population that it serves, is unlikely to meet the needs and demands of its population. Mortality indicators are the most basic tools in epidemiology, the central role of health authorities is to decrease mortality and morbidity.

Information linked to surveillance systems is the best tool for early prevention and risk management. In surveillance systems, notification of diseases is the early step in data collection.

With the spread of information technology, the potential of e-health solutions as electronic medical records for health service management and telemedicine are well recognized [19]. These would enhance coordination of clinicians, promote efficiency, increase effectiveness and overall quality, and improve safety [19].

Community participation

Notwithstanding the overall responsibility of the central and state governments, the involvement of individuals, families, and communities in promoting their own health and welfare is an essential ingredient of health care. The Nanny State, which presumes to know individuals’ needs better than they can determine for themselves is a hazard to the well functioning of the state and to the population it serves. It stifles freedom and initiative; and increases dependence, service abuse and moral hazard [6]. A vivid example is the return of diphtheria in the former Soviet Republics upon collapse of the state after a long period of diphtheria control. Universal coverage by health care cannot be achieved without the involvement of the local community [20]. Besides maximum reliance on local resources such as manpower, money and materials, there must be a continuing effort to secure meaningful involvement of the community in the planning, implementation and maintenance of health services. By increasing the role of patients, health care providers should become more responsive to patients’ needs and preferences and would deliver better quality care. Patients can participate in health care in many ways. The degree of participation ranges from simple involvement as getting the opinion of the public in basic amenities of health services, such as clean waiting rooms or adequate beds and food in hospitals, and consumer satisfaction to higher degrees of participation forms as empowerment of the community [21].

Intersectoral cooperation and advocacy

Health care cannot be provided by the health sector alone [20]. Health care involves also all related sectors of national and community development as agriculture, animal husbandry, food, industry, education, housing, public works, communication, transports and other sectors. To achieve such cooperation, countries may have to review their administrative system, reallocate their resources and introduce suitable legislations to ensure that coordination can take place. This advocacy of health in other sectors is a part of the stewardship function of the state. We take nutrition as an example, where provision of adequate food supply relies on sectors as agriculture, industry, economy and transport, while its utilization is related to education and economy. Temporary, short, and intermediate term solutions as subsidizing policies on imported food items have many disadvantages even from a health point of view. Besides discouraging local production, consumer's subsidizing policies encourage consumption of nutritional goods of low nutritional values. Alternatively, they may be used to discourage or encourage certain foods. Subsidizing policies are also used at producers level to increase production of certain food items.

Health knowledge and education

Information is a prerequisite for community participation that would enable them to make informed judgments about health care issues. However, the public often lacks optimum information. Access to health information should be recognized as a human right. Technical information should be presented in language that would inform the public. Occasionally, there is deliberate suppression of information by government's officials. For example, there is a tendency to cover up information about outbreaks of infectious diseases like cholera, HIV/AIDS, etc. Individuals and communities often lack the knowledge on how to keep healthy, how to recognize dangerous signs in the individual and hazardous situations in the environment and how to mobilize resources to solve health problems. They should be educated on different aspects of common, endemic and serious health problems.

Equity

Health inequalities are found in many countries [22]. Equity in health means fairness and justice. It has different aspects as; health status of different families, countries and population groups; allocation of resources; and access to and utilization of services. Gender and urbanity are important subgroups to be considered for equity. Gender equity is assessed by the differences in prevalence of undernutrition. As a part of its stewardship function, the state should insure that health services are affordable for the needing individuals, irrespective of their financial status. No one should have to make a choice between withholding treatment and becoming impoverished or in debt to get that treatment. Everyone should be protected from financial risks due to health care [1]. Differences may occur due to the concentration of local human resources (HR) in certain regions, or due to cultural, educational, accessibility, life style or other factors. Every policy within or outside the health sector should be critically examined as to its likely effect on equity in health. Examples are the impact of macroeconomic policies, the structured economic readjustment programs on public investment in health and other social sectors and the increasing contribution of the private market in health delivery. Equity should be monitored with the universal growing role of the private market.

Resources

Resource generation (physical, human, and knowledge) is a part of stewardship of the state [1]. Health system financing is the main component of physical resources. Financing is the process by which revenues are collected from primary and secondary sources, accumulated in fund pools, and allocated to provider activities [1]. Severe resource constraint is a major issue in designing and managing the health services in developing, as well as industrialized countries [22]. Industrial and affluent societies have a spending of US$ 1000–3000 per head annually, while the poorest countries spend less than US$ 20 per head annually. In many countries such as the USA, if healthcare spending continued to outpace income growth, the whole budget might, consequently, go to healthcare [23]. It is vital to ensure that the limited resources are wisely spent so as to achieve the maximum returns for minimum expenditure. Tough choices sometimes have to be made. Nations have rationed health care for years by restraining the rate of social spending, setting health care budgets or regulated fees, effectively controlling the numbers of hospitals or the amount of medical equipment, or other devices. Many such measures could endanger quality [23]. Many factors would increase health expenditure as; increase in the size of the population; new expensive modes of treatment; changing patterns of disease; discovery of new illnesses; and the expected further wave of high-tech medicine that is coming over the horizon.

Against previous expectations, private medical practice did not just disappear [24]. However, over-reliance of the private market on consumer oriented systems should not be the only option. Hospitals everywhere face crises and cost containment is a real issue. Hospitals’ relatively high expenditure should be assessed in terms of effectiveness, efficiency and efficacy. It is important that terms such as analytical accounting, efficiency, priorities settings, the contributory principle, risk extrapolation on the budget, and prevention of moral hazard find their place in different national health services.

Financial resources alone are not sufficient as human resources (HRs) comprise a central component for the performance of health systems [2, 22,25]. They consume a major share of resources [2]. The weakness of HRs would limit the impact of any new financial resources [22]. Poorly performing HRs are a risk not only to patients but also to the organization they work for [10]. HRs in health is characterized by diversity and complexity as it includes people from a wide range of occupational backgrounds trained in a variety of institutional settings [22]. Examples include physicians, nurses, health managers, occupational health and safety personnel, health economists, environmental health specialists and health promoters [22]. Critical workforce shortages have to be managed. National HR policies are required for giving direction on HR development and linking HRs into health-sector reform [25]. HRs are influenced by a series of organizational, managerial, social, economic, cultural, and gender-related factors. The workplace environment has a great impact on health worker performance, and on the comprehensiveness and efficiency of health service delivery. Poor working conditions may be contributing to both numerical and distributional imbalances in many countries. The use of monetary and non-monetary incentives in the health-sector is of crucial importance [25]. Valuing staff and letting them know that they are valued is easily accepted but is often overlooked. This valuing is a common feature of organizations that show sustained excellence in other sectors [10]. Continuous education and training of HRs is an essential ingredient of health services. Medical sciences grow by about 10% each year. Unless mechanisms of acquisition of knowledge and practical training are ensured, the quality of these HRs would be questionable. Continuous education has been neglected in wealthy and poor countries alike [22]. Efforts should be strengthened to diversify skills and training of local HRs and to develop an evidence base on HRs for health [2]. The appropriate roles of the workforce, their training needs, the development of appropriate career structures and research, and their current functions and performance should be specified [22]. A long-term effort to develop stewardship and technical and leadership skills within the health profession is important for capacity building [10]. Clinicians and administrators should be taught how to best use limited resources [26]. New approaches such as problem based learning, value of researches and joint education with other professional disciplines should be instituted to undergraduate medical education [10]. The most important vehicle for added knowledge is through periodicals and congress attendance. Training and knowledge acquisition of manpower should be supported by documentary resources using e-health solutions including access to specialist databases [10], or using a national database with multiple categories of periodicals and other resources linked together by a central organism, or projects as HINARI and/or other similar project as, eIFL.net, AGORA, and OARE.

Quality of health services

A commitment to deliver high quality care should be at the heart of every-day clinical practice [10]. It is vital that poor performance be recognized and dealt with [10]. Detection of failure(s) in the standards of care-giving, whether through complaints, audit, untoward incidents, or routine surveillance is an essential component for the recognition and proper functioning of health services delivery [10]. Quality of care is a multidimensional concept. Individuals should not take decisions in isolation and practices should be evidence-based (10). Health interventions and health services should fulfil certain criteria to insure proper functioning. There are different aspects of quality that require different methods of measurements [27]. Quality is divided into four aspects: professional performance (technical quality); resource use (efficiency); risk management (the risk of injury or illness associated with the service provided); and patients’ satisfaction with the service provided [28]. Increasing the role of patients would improve quality of care [21]. Projects should not be limited to building and construction but should include goals, objectives and targets. Audits should not be restricted to inspection of administrative procedures but rather performance assessment. There should be appropriate selection of useful indicators to monitor progress and assess the effectiveness of proposed projects, programs, and policies in reaching their stated goals. Various performance indicators for monitoring, assessing, and managing health systems to achieve effectiveness, equity, efficiency, and quality were developed [29]. Examples of such indicators in evaluation of hospital activities are shown in Table 3. Outcome indicators should be properly selected and be relevant to the objectives of care. Different aspects for evaluation of performance in the health establishment should be considered. These should include structure indicators, process indicators and outcome indicators. Services should be assessed for effectiveness, efficiency and utilizing the available resources to make the desired change. We take a situation where interventions A and B are both helpful in treatment of disease X. If intervention A treats more patients than intervention B does, then A is more effective than B. Besides, when both interventions treat the same proportion of patients and are equally effective, but B is cheaper than A, then intervention B is more efficient than intervention A. Another important aspect of health services are efficacy or real time effectiveness, acceptability, appropriateness and accessibility. Retrospective and prospective indicators such as control charts, which are graphs that can take the uncertainty out of decision making through the analysis of relationships between data points plotted over time, should be used to improve quality [30]. Other similar methods include run charts, process flowcharts, Pareto analysis, fishbone diagrams, etc [30]. Output indicators include mortality, relative survival rate after diagnosis, and disability-adjusted life expectancy [31]. There is always concern about the use and abuse of publicly available indicators [32].

Table 3.

Examples of Indicators that may be used in evaluations of hospitals

| Indicator | |

|---|---|

| Hospital activity | The number of key procedure interventions performed during the year. |

| Notoriety | The proportion of patients treated in a hospital and live geographically far from it. |

| Ambulatory activity | The proportion of cases treated in daycare departments compared to those treated as inpatients in certain types of interventions. |

| Technicity | The ratio of complex or high tech. interventions to simple or older ones. |

| Specialization | The degree of orientation of certain members within a team towards specific intervention within a large discipline. |

| Severity Index of treated cases | The capacity of an establishment to manage with the most difficult cases within certain pathology. |

| Control of Nosocomial infections | Various composite indices are used for surveillance of nosocomial infections. Examples are the National Nosocomial Infection Surveillance score (NNIS) from the Center for disease control and prevention (CDC), SSI risk score, French Aggregated score (ICALIN, ICSHA, SURVISO and ICATB). |

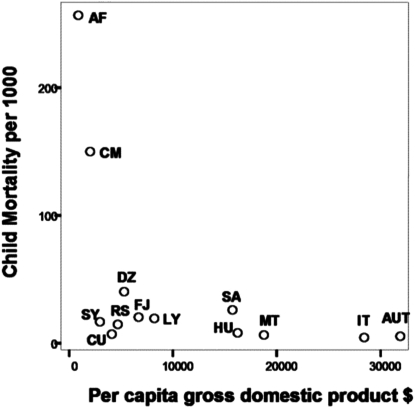

A good example of intelligent indicator is the UNICEF's national performance gap where the observed level of the specific health indicator is compared with the rate predicted on the basis of the gross national product of the country (Figure 3). Countries with best performance are those in the left lower corner, while the worst are those in the left upper zone.

Figure 3.

National performance gap scatter plot showing children mortality in some chosen countries in relation to per-capita gross domestic product. [SY: Syria, SA: Saudi A, RS: Serbia, MT: Malta, LY: Libya, IT: Italy, HU: Hungry, FJ: Fiji, CU: Cuba, CM: Cameroon, UT: Australia, DZ: Algeria, AF: Afghanistan]. Higher mortality or intermediate mortality in spite of higher income depicts low performance systems

Evaluating physician competence is an essential component of quality assurance. Apparatus of formal assessment is necessary to assure fairness, predictability, stability and legitimacy. Physician assessment should include area of responsibility, level of responsibility, and means used for assessment [33]. Competence should include attributes, activities and accomplishments in addition to management of physical illness. But other aspects should also be included such as cognitive, psychological and social needs that are to be satisfied in the patient-physician relationship [33]. Nothing is more destructive to morale than a procedure for assessment based on unverified impressions, using private criteria, that is carefully and selectively applied [33].

Well-managed organizations are those in which financial control, service performance, and clinical quality are fully integrated at every level [10]. Evaluation should be a continuous process at periodic intervals rather than a sporadic event. It should be practiced by independent external bodies, the functions of which should be inspecting, investigating, advising, supplying expertise, facilitating and accrediting [10]. The aim should be introducing rigorous measurement to the business of improvement, rather than making judgments and scapegoating [30]. Quality improvement with punitive approaches should not be encouraged [32]. It should put appraising evidence, developing and disseminating guidance and audit methods, and accepting lifelong learning attitude [32].

Improvement could be accomplished in different organizations by new approaches such as clinical governance. This concept was imported from corporate governance and used in the healthcare system to describe a systematic approach to maintaining and improving the quality of patient care. It is an organization-wide approach to quality improvement with emphasis on preventing adverse outcomes through amplifying and improving the process of care. The elements of clinical governance are education and training, clinical audit, clinical effectiveness, research and development, openness, and risk management. With good governance, where the policy and institutional environment are sound and supportive, good outcomes occur in health even with low levels of expenditure. Conversely, where the policy and institutional environment are weak, one can find poor health outcomes even in the context of adequate expenditures [9]. Governance embodies recognizably high standards of care, transparent responsibility and accountability, and a constant dynamic of improvement. It necessitates leadership and commitment from the top of the organization, team work, consumer focus, and good data [10]. It makes a working environment which is open and participative, where ideas and good practice are shared, education and research are valued, and blame is rarely used, focus is on processes and emphasis is on team learning [10, 30]. The real challenge is the active development of such cultures in most hospitals and primary care groups [10].

References

- 1.Murray CJ, Frenk J. A framework for assessing the performance of health systems. Bull World Health Organ. 2000;78(6):717–731. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Diallo K, Zurn P, Gupta N, Dal Poz M. Monitoring and evaluation of human resources for health: an international perspective. Hum Resour Health. 2003;1(1):3. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-1-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saltman RB, Ferroussier-Davis O. The concept of stewardship in health policy. Bull World Health Organ. 2000;78(6):732–739. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Banihashemi K MP, Naeeni SMK. Experience Of Establishing A Society-Based Health Care System: Few Considerations May Lead To So Many Advantages. The Internet Journal of Healthcare Administration. 2006;4(1) [Google Scholar]

- 5.McPake B, Mills A. What can we learn from international comparisons of health systems and health system reform? Bull World Health Organ. 2000;78(6):811–820. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Musgrove P. Health insurance: the influence of the Beveridge Report. Bull World Health Organ. 2000;78(6):845–846. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ham C. Improving NHS performance: human behaviour and health policy. BMJ. 1999;319(7223):1490–492. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7223.1490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ham C. From targets to standards: but not just yet. BMJ. 2005;330(7483):106–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.330.7483.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feachem RG. Health systems: more evidence, more debate. Bull World Health Organ. 2000;78(6):715. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scally G, Donaldson LJ. The NHS's 50 anniversary. Clinical governance and the drive for quality improvement in the new NHS in England. Bmj. 1998;317(7150):61–65. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7150.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Freeman T, Walshe K. Achieving progress through clinical governance? A national study of health care managers’ perceptions in the NHS in England. Qual Saf Health Care. 2004;13(5):335–343. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2002.005108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith PC. Performance management in British health care: will it deliver? Health Aff (Millwood) 2002;21(3):103–115. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.21.3.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mays GP, McHugh MC, Shim K, Perry N, Lenaway D, Halverson PK, et al. Institutional and economic determinants of public health system performance. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(3):523–531. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.064253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bahamon C, Dwyer J, Buxbaum A. Leading a change process to improve health service delivery. Bull World Health Organ. 2006;84(8):658–661. doi: 10.2471/blt.05.0287872. discussion 662–663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bodenheimer T. Primary care--will it survive? N Engl J Med. 2006;355(9):861–864. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp068155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Woo B. Primary care--the best job in medicine? N Engl J Med. 2006;355(9):864–866. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp068154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levey M. Fourteenth century Muslim medicine and the Hisba. Med Hist. 1963;7:176–182. doi: 10.1017/s0025727300028209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Park K. Park's Textbook of Preventive and Social Medicine. 14th ed. Jabalpur (India): M/s Banarsidas Bhanot Publishers; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 19.El Taguri A. The need to introduce Telemedicine in Libya; First Libyan conference on medical specialities; Benghazi: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Declaration of Alma-Ata. WHO Chron. 1978;32(11):428–430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wensing M. Evidence-based patient empowerment. Qual Health Care. 2000;9(4):200–201. doi: 10.1136/qhc.9.4.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beaglehole R, Dal Poz MR. Public health workforce: challenges and policy issues. Hum Resour Health. 2003;1(1):4. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-1-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aaron H. Health Policy Issues & Options, Policy Brief # 147. 2005. Health Care Rationing: What it Means. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beveridge W. Social insurance and allied services. 1942. Bull World Health Organ. 2000;78(6):847–855. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wyss K. An approach to classifying human resources constraints to attaining health-related Millennium Development Goals. Hum Resour Health. 2004;2(1):11. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-2-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Braham RL. Teaching about cost-effective use of medical resources: still trying after all these years. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(6):419–421. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016006419.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Campbell SM, Hann M, Hacker J, Burns C, Oliver D, Thapar A, et al. Identifying predictors of high quality care in English general practice: observational study. BMJ. 2001;323(7316):784–787. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7316.784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Health for all in the 21th century. World Health Statistics Quarterly. Vol. 52. Geneva: World health organisation; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arah OA, Klazinga NS, Delnoij DM, ten Asbroek AH, Custers T. Conceptual frameworks for health systems performance: a quest for effectiveness, quality, and improvement. Int J Qual Health Care. 2003;15(5):377–398. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzg049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wilcock PM, Thomson RG. Modern measurement for a modern health service. Qual Health Care. 2000;9(4):199–200. doi: 10.1136/qhc.9.4.199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lakhani A, Coles J, Eayres D, Spence C, Rachet B. Creative use of existing clinical and health outcomes data to assess NHS performance in England: Part 1--performance indicators closely linked to clinical care. Bmj. 2005;330(7505):1426–1431. doi: 10.1136/bmj.330.7505.1426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thomson R. Quality to the fore in health policy--at last. But the NHS mustn't encourage quality improvement with punitive approaches. BMJ. 1998;317(7151):95–96. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7151.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Donabedian A. Evaluating physician competence. Bull World Health Organ. 2000;78(6):857–860. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]