Abstract

Aims

The aims of this study were to assess the prevalence of self-reported halitosis, oral hygiene practices and related diseases among Libyan students and employees.

Methods

Six hundred self-administered structured questionnaires were used to investigate self-perception of halitosis and oral hygiene practices among a group of Libyan volunteers. Chi square test was used to detect significant differences between frequencies and to test correlation between self-perception of halitosis and measures of oral hygiene.

Results

Forty three percent of the subjects were males and 57% were females. Forty four percent of the males and 54% of the females revealed self-perception malodour. Malodour was reported with the highest frequency (68%) during wake up time. Malodour was perceived by 31.7% of the females and 23.4% of the males during the hand-on-mouth test (p=0.04). Significantly more females (89.9%) than males (75.7%) practiced brushing (p<0.001). Fifty one percent of the males and 49.6% of females had dental caries. Smoking was significantly (p<0.001) more prevalent among males (17%) than among females (1%). Brushing was practiced by 85% of non-smokers and 68% of smokers (p=0.004). About 71% of the subjects who practiced brushing reported malodour during wake up time in comparison to subjects who did not practice brushing (p=0.041).

Conclusions

The prevalence of self-perceived malodour among the Libyan volunteers in this study is within the range of other studies. There is a great demand to reduce the incidence of dental caries and periodontal diseases.

Keywords: self-reported halitosis, dental caries, oral hygiene practices, gum bleeding

Introduction

Halitosis is a universal medico-social problem in all communities and refers to the unpleasant odour that emanates from the mouth. The condition is multifactorial in aetiology and may involve both oral and non-oral conditions. Halitosis is a general term used by some authors to describe the condition regardless of its origin [1]. The term oral malodour is consistently indicative of intra-oral causes.

Halitosis has been classified into three main categories: genuine, pseudo-halitosis, and halitophobia halitosis [2]. In genuine halitosis, the malodour intensity is beyond the socially acceptable level. If malodour is not perceived by others but the patient persistently complains of its existence, it is diagnosed as pseudo-halitosis. If after successful treatment of genuine halitosis or pseudo-halitosis the patient still complains of halitosis, the diagnosis is referred to halitophobia.

There is a general agreement that malodour originates in the mouth in 80–90% of cases [3]. There is evidence that on waking up in the morning most healthy adults have socially unacceptable bad breath [4]. This problem is attributed to reduced saliva flow during sleep, and it is usually resolved after washing and eating breakfast. Several factors may contribute to oral malodour, including tongue coating, deep carious lesions, exposed necrotic tooth pulps, periodontal disease, pericoronitis, mucosal ulcerations, healing oral mucosa wounds, peri-implant disease, impacted food or debris, imperfect dental restorations, unclean dentures and oral carcinoma [5–15].

Volatile sulphur compounds (VSC), namely hydrogen sulphide (H2S) and methyl mercaptan (CH3SH) are the main cause of oral malodour [16]. These substances are by-products of the action of bacteria on proteins. A recent study demonstrated that mercaptan is the main contributor of intra-oral halitosis, while dimethyl sulphide (C2H6S) is the main contributor of extra-oral or blood-borne halitosis [17]. However, other substances, such as organic acids, ammonia and amines, have also been implicated in oral malodour [18, 19].

The aetiologies of non-oral malodour include upper respiratory tract problems, particularly sinusitis and polyps [20], gastrointestinal tract disturbances [21, 22], and some metabolic disorders such as diabetes mellitus [23]. Oral malodour is also noticed after eating certain foods, such as garlic, and among heavy smokers. It may also manifest as a side-effect of some drugs that reduce salivary flow, such as antidepressants, antihistamines, antipsychotics, antihypertensives, decongestants and narcotics [24–27].

The prevalence of oral malodour varies in different parts of the world. In western societies, embarrassment and discomfort are the main reasons for seeking professional care. A thorough literature search reveals lack of studies on halitosis in Libya.

Aims of the study

Our aim was to investigate the prevalence of halitosis, oral hygiene practices and related oral diseases, such as dental caries and periodontal diseases among a sample of Libyan students and employees.

Materials and methods

In a pilot study of 65 volunteers, we used the self-administered questionnaire previously used by Almas et al [28]. Based on the results, we introduced some modifications in the questionnaire. The modified structured questionnaire (see appendix) was self-administered to six hundred Libyan volunteers at 3 universities, 7 schools, 4 government departments and 5 private accounting and consultation offices. Each, were given a certain number of questionnaires to complete. All volunteers were over the age of 12 years.

An Arabic information sheet explaining the need for the study and the procedure for responding to the questionnaire was enclosed as a cover sheet.

The data was entered into a FoxPro database and imported into Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 12.0 for analysis. Questionnaires with missing data were excluded from the study. The data was analyzed for frequency distributions, and the Chi-square test was used to find significance of differences between frequencies and to test for correlation between halitosis and variables of oral hygiene practices. The significance level (p-value) was set at 0.05.

Result

Of 600 questionnaires distributed, 102 were either not returned or were incomplete, leaving 498 questionnaires for the analysis. Non-respondents included students at schools and universities and employees in the public and private sectors. No obvious differences were noticed between respondents and non-respondents.

Self-perceived malodour was reported by 44% of the males and 54% of the females, and 13.1% of the females and 13.6% of the males were unable to decide if they had malodour (Table 1). Approximately 14% of males and 13% of females were examined for malodour by a dentist, whereas 1.5% of males and 1.3% of females were examined by a physician. Dentists provided treatment for 9.6% of the subjects, and only 1.8% of the respondents were treated by physicians.

Table 1.

Prevalence of self-reported oral malodour and interference with social life

| Self-perception of oral malodour | Interference with social life | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Yes (%) | No (%) | Don't know (%) | Total | Yes | No (%) | Don't know (%) |

| M | 95 (44.4) | 90 (42) | 29 (13.6) | 214 | 27 (12.6) | 155 (72.4%) | 32 (15%) |

| F | 154 (54.2) | 93 (32.7) | 37 (13.1) | 284 | 35 (12.3%) | 220 (77.5%) | 29 (10.2%) |

| Total | 249 | 183 | 66 | 498 (100%) | 62 | 375 | 61 |

| p=0.072 | p=0.123 | ||||||

*P value=difference between males and females

Twenty eight percent of the males and 33.1% of the females used commercial products, such as mouth wash and mint chewing gum. Use of traditional medicine, such as clove oil, was reported by 20.6% and 15.5% of the males and females, respectively.

As shown in Table 2, 30–39% of the subjects reported having relatives who complain of malodour. Females reported a significantly higher prevalence of malodour among relatives than males (p= 0.001). A nearly equal proportion of males and females reported that bad breath had interfered with their social life or with their work during the previous month (Table 1). Malodour was reported with the highest frequency (68%) during wake up time. In 20–23% of the respondents, malodour was perceived during thirst or hunger. A small percentage (<10%) of the respondents, reported malodour during morning, talking, afternoon or throughout the day.

Table 2.

Prevalence of malodour among relatives

| Gender | Relatives' malodour | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Don't know | |

| Male | 66 (30.8%) | 87 (40.7%) | 61 (28.5%) |

| Female | 112 (39.4%) | 109 (38.4%) | 63 (22.2%) |

| p=0.001 | |||

*P value=difference between males and females

In the hand-on-mouth test, there was a significant difference in prevalence of self-perceived malodour between males and females (23% and 32%, respectively, p=0.04, (Table 3).

Table 3.

Frequency of self-perceived malodour according to hand-on-mouth test

| Gender | Yes (%) | No (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Male | 50 (23.4) | 164 (76.6) |

| Female | 90 (31.7) | 194 (68.3) |

| Total | 140 | 358 |

| p=0.041 | ||

*P value=difference between males and females

A wide variety of oral hygiene practices was observed (Table 4). Almost 90% of the females practiced brushing regularly, which is a significantly higher proportion (p<0.001) than for males (75.7%). About 64% of the subjects who practiced brushing reported malodour during wake up time.

Table 4.

Distribution of oral hygiene practices among males and females

| Variable | Male | Female | Significance | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Yes | No | p-value | |

| Brushing | 162 | 52 | 255 | 29 | 0.000 |

| 75.7% | 24.3% | 89.9% | 10.1% | ||

| Flossing | 44 | 170 | 63 | 221 | 0.663 |

| 20.6% | 79.4% | 22.2% | 77.8% | ||

| Mouth wash | 31 | 182 | 45 | 239 | 0.476 |

| 14.5% | 85% | 15.8% | 84.2% | ||

| Tooth picks | 84 | 130 | 68 | 216 | 0.000 |

| 39.3% | 60.7% | 23.9% | 76.1% | ||

| Miswak | 51 | 163 | 31 | 253 | 0.001 |

| 23.8% | 76.2% | 10.9% | 89.1% | ||

*P value=difference between males and females

About 21% of the respondents used dental floss, while mouthwash was used by about 15%. Use of tooth picks was significantly more among males (39%, p<0.001), when compared with females (24%). About 61% of the subjects who used tooth picks had malodour during the wake up time.

There had been significant differences in use of miswak as well. Twenty four percent of the males used miswak in comparison to 11% of females (p=0.001).

Fifty one percent of the males and 49.6% of females had dental caries. Bleeding gums was reported by an almost equal proportion of females and males (31.3% and 33.2%, respectively). Forty seven percent of the males and 40% of the females described having a tongue coating.

Smoking habits among males and females showed a significant difference (p<0.001); about 17% of males and 1% of females were smokers. Use of tooth brush was significantly more prevalent (p=0.004) among non-smokers (85%) than among smokers (68%).

The prevalence of dry mouth was almost similar between females and males (20% and 22%, respectively). Drinking of tea was significantly more common among males than females (53% and 34%, respectively; p<0.001). Similarly, coffee-drinking practice was seen to be more common among males than females (35% and 30%, respectively).

Chi square test analysis revealed no correlation between self-perceived malodour and oral hygiene variables.

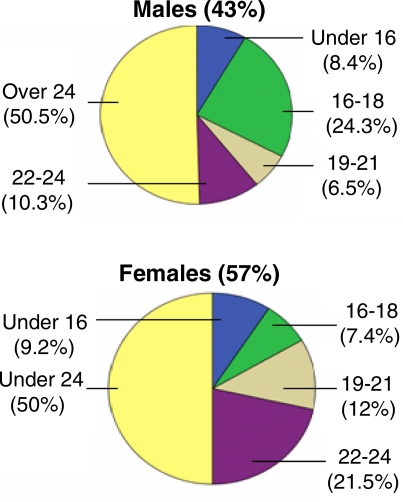

Figure 1.

Age distribution of males and females

Discussion

Oral malodour is a common problem among general population and evidences reveal that it forms about 85% of all bad breath [20]. In spite of the wealth of information on the condition, identification of the actual cause remains sometimes difficult. In many studies, including ours, the assessment of malodour relies on the subject's self-perception. Many professionals do not consider this method to be reliable because it is subjective, and obviously, the method is not standardized among participants. Nevertheless, despite its shortcomings, this method has been the most commonly used organoleptic technique of evaluating malodour [29].

Malodour is common among all ages [30]. We found that 25% of the respondents aged 12–16 years claimed to have noticed that their oral breath smelled bad. Furthermore, when these volunteers were asked to do the hand-on-mouth test, 36% of them were positive. Many families have long been taught that the mouth is the sole source of bad odour and are unaware of the other factors such as enlarged tonsils or nasal polyps that might cause this condition, particularly in children. Therefore, the dental surgeons are encouraged to perform a thorough examination if no oral etiologies are apparent.

Self-perception of malodour was reported by 44% of the males and 54% of the females. Although these figures are within the range of other studies [28, 31] and the differences are insignificant, it appears that females were more capable of detecting malodour than males. However, these findings can not be ascertained, as the self-estimation procedure is subjective and correlates poorly with objective assessment of patient's perception of bad breath [32]. Furthermore, females are invariably more concerned about their oral hygiene and appearance and this may explains the over-exaggerated self-perception percentage [4]. About 14% of the respondents were diagnosed by dentists, who provided treatment for approximately 10% of these subjects. On the other hand, a few respondents 2–2.5% approached physicians for diagnosis, and an even less number 1.8% were given treatment or advice by physicians. Diagnosis of oral malodour is primarily the responsibility of the dental surgeons. In view of the widespread awareness of malodour, the small percentage 14% diagnosed by dentists reflects their negative role in detection and treatment of the condition.

Special clinics or centers that deal with such conditions have not yet been established in Libya. Moreover, our considerable experience of working in Libya leads us to believe that dental professionals in the community services and in the private sector do not devote adequate time and efforts for proper examination of patients with bad breath. Consequently, if a dental cause is not evident, patients are quite likely prescribed a mouthwash.

Bad breath can have a distressing effect that may become a social handicap and the affected person may avoid socialising. In this study, almost equal percentages of males and females admitted that oral malodour interfered with their social life. Interestingly, the females reported significantly more relatives complaining of oral malodour than males, but the differences can not be explained.

A considerable percentage of our participant subjects 66–70% reported malodour on awakening and 20–23% when they were thirsty or hungry. Sleeping, being hungry or thirsty would certainly reduce saliva flow and lead to oral malodour. This is noticeable during the fasting month Ramadan, when people abstain from drinking and eating for hours. However, in those conditions the bad breaths are temporary and disappear once food or drinks are taken, and should not be regarded as true malodour. Only 10% of the participants revealed malodour during talking, in the morning, afternoon or through out the day. These figures are comparable with a previous study in Saudi Arabia [28].

It has been estimated that in the developed world, 8–50% of people perceive oral malodour [30]. The participants in this study were asked to assess their oral breath by using the hand-on-mouth technique self-perceived malodour. More females 32% reported oral malodour than males 23% at the time of completing the questionnaire.

These differences may be related to the common trend observed among females and their frequent seeking of treatment.

Lack of oral hygiene, including brushing, use of anti-plaque mouthwashes and flossing, has been implicated in oral malodour [16, 33–34]. In this study, the frequency of brushing was almost 90% in females and 76% in males. This significant difference between females and males do not correlate with the prevalence of self-perceived malodour of the females. The floss and mouth washes had been used by less than one quarter of the subjects. Use of tooth picks is common among males 39% in the Libyan community but less so among females 24%.

Miswak a traditional chewing stick is a natural toothbrush made from twigs of the Salvadora Persica tree. It is widely used in the Middle East, particularly in Saudi Arabia. It has an antibacterial effect and is as good as tooth brush in removing dental plaque and reducing gingivitis [35]. Its use among Libyans is infrequent; particularly by females and the majority of the populations are unaware of its effectiveness in prevention and treatment of periodontal diseases. Therefore, the population should be acknowledged of its merits and encourage its use.

Some studies have reported correlations between measures of oral hygiene and oral malodour [28, 34]. However, in our study we did not observe such a correlation. In fact 71% of the subjects who practiced regular brushing and 61% of the subjects used tooth picks revealed malodour after wake-up. In line with these findings, John and Vandana [36] could not correlate malodour grading with periodontal clinical parameters, such as plaque index, gingival index, gingival bleeding index and pocket depth measurements. The correlation between clinical parameters and oral hygiene practices on one hand and oral malodour on the other requires further investigation.

On average, 50% the subjects had dental caries and 31% had gum bleeding. Dental caries and periodontal diseases are potential factors contributing to the bad breath. However, in the present study neither showed any correlation with the oral malodour. Coated tongue is probably the most implicated factor in the etiology of the oral malodour as a result of bacterial fermentation and subsequent release of VSC and other products [37]. The coated tongue was noticed by 47% of the males and about 40% of the females. It has been thought that scraping of the tongue as a part of oral hygiene results in reduction of malodours and bacteria [38, 39], a recent study however; found no differences [40].

Smoking has been defined as an extrinsic cause of oral halitosis [10]. Seventeen percent of the males and 1% of the females were smokers. The stereotype in the Libyan community females are non-smokers. Our study shows that fewer smokers brushed their teeth than non-smokers. However, smoking showed no association with self-perceived malodor.

Mouth dryness was reported by 20% of the females and 22% of the males. Low salivary flow xerostomia reduces the oral cleansing effect and enhances tongue coating and potential malodour [41].

Tea is one of the most preferred drinks in the culture. The number of males drinking tea 53% significantly exceeded the females 35%. Also, the males drinking coffee were slightly more than the females. Information available on the role of these two drinks in oral malodour is scarce, though some studies reported an association between drinking tea or coffee and reduction in certain oral microorganisms [42].

In conclusion, our results indicate that the prevalence of self-perceived malodour among Libyans is within the range reported by other studies. However, these findings need to be corroborated by objective examination to ascertain the prevalence. The public is probably not fully aware of the potential causes of oral malodour and its treatment. The role of dental professionals in maintaining good oral health should be emphasized in the community. There is a great demand to control and reduce the incidence of the dental caries and periodontal diseases. These two ailments require special attention and efforts to minimize their complication.

The smokers should be encouraged to refrain from smoking and practice brushing. The study recommends further investigations using the standard clinical methods available to assess the bad breath problem.

A Questionnaire about Oral Hygiene, Smoking and Self-Perceived Oral Malodor Among Libyan population

References

- 1.Tonzetich J. Production and origin of oral malodor: a review of mechanisms and methods of analysis. J Periodontol. 1997;48:13–20. doi: 10.1902/jop.1977.48.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yaegaki K, Coil JM. Examination, classification and treatment of halitosis; clinical perspectives. J Can Dent Assoc. 2000;66:257–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benninger M, Walner D. Coblation: improving outcomes for children following adenotonsillectomy. Clin Cornerstone. 2007;9:13–23. doi: 10.1016/s1098-3597(07)80005-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sanz M, Roldán S, Herrera D. Fundamentals of breath malodour. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2001;15:1–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spielman AI, Bivona P, Rifkin BR. Halitosis. A common oral problem. N Y State Dent J. 1996;62:36–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu XN, Shinada K, Chen XC, Zhang BX, Yaegaki K, Kawaguchi Y. Oral malodour-related parameters in the Chinese general population. J Clin Periodontol. 2006;33:31–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2005.00862.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Delanghe G, Ghyselen J, van Steenberghe D. Experiences of a Belgian multidisciplinary breath odour clinic. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Belg. 1997;51:43–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yaegaki K, Sanada K. Volatile sulfur compounds in mouth air from clinically healthy subjects and patients with periodontal disease. J Periodontal Res. 1992;27:233–238. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1992.tb01673.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yaegaki K, Sanada K. Biochemical and clinical factors influencing oral malodour in periodontal patients. J Periodontol. 1992;63:783–789. doi: 10.1902/jop.1992.63.9.783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morita M, Wang HL. Relationship of sulcular sulfide level to severity of periodontal disease and BANA test. J Periodontol. 2001;72:74–78. doi: 10.1902/jop.2001.72.1.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morita M, Wang HL. Relationship between sulcular sulfide level and oral malodour subjects with periodontal disease. J Periodontol. 2001;72:79–84. doi: 10.1902/jop.2001.72.1.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morita M, Musinski DL, Wang HL. Assessment of newly developed tongue sulfide probe for detecting oral malodour. J Clin Periodontol. 2001;28:494–496. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2001.028005494.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kleinberg I, Wolff MS, Codipilly DM. Role of saliva in oral dryness, oral feel and oral malodour. Int Den J. 2002;52:236–240. doi: 10.1002/j.1875-595x.2002.tb00932.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hinode D, Fukui M, Yokoyama N, Yokoyama M, Yoshioka M, Nakamura R. Relationship between tongue coating and secretory-immunoglobulin A level in saliva obtained from patients complaining of oral malodour. J Clin Periodontol. 2003;30:1017–1023. doi: 10.1046/j.0303-6979.2003.00407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Steenberghe D. Breath malodour: a step by step approach. Copenhagen: Quintessence Publishing; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feller L, Blignaut E. Halitosis: a review. SADJ. 2005;60:17–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tangerman A, Winkel EG. Intraand extra-oral halitosis: finding of a new form of extra-oral blood-borne halitosis caused by dimethyl sulphide. J Clin Periodontol. 2007;34:748–755. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2007.01116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van den Broek AM, Feenstra L, de Baat C. A review of the current literature on aetiology and measurement methods of halitosis. J Dent. 2007;35:627–635. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2007.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Amano A, Yoshida Y, Oho T, Koga T. Monitoring ammonia to assess halitosis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2002;94:692–696. doi: 10.1067/moe.2002.126911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rosenberg M. Clinical assessment of bad breath: current concepts. J Am Dent Assoc. 1996;127:475–482. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1996.0239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoshi K, Yamano Y, Mitsunaga A, Shimizu S, Kagawa J, Ogiuchi H. Gastrointestinal diseases and halitosis: association of gastric Helicobacter pylori infection. Int Dent J. 2002;52:207–211. doi: 10.1002/j.1875-595x.2002.tb00926.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saberi-Firoozi M, Khademolhosseini F, Yousefi M, Mehrabani D, Zare N, Heydari ST. Risk factors of gastroesophageal reflux disease in Shiraz, southern Iran. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:5486–5491. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i41.5486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reiss M, Reiss G. Bad breath--etiological, diagnostic and therapeutic problems. Wien Med Wochenschr. 2000;150:98–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murata T, Fujiyama Y, Yamaga T, Miyazaki H. Breath malodour in an asthmatic patient caused by side-effects of medication: a case report and review of the literature. Oral Diseases. 2003;9:273–276. doi: 10.1034/j.1601-0825.2003.02874.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scully C, el-Maaytah M, Porter SR, Greenman J. Breath odor: etiopathogenesis, assessment and management. Eur J Oral Sci. 1997;105:287–293. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1997.tb00242.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Durham TM, Malloy T, Hodges ED. Halitosis: knowing when ‘bad breath’ signals systemic disease. Geriatrics. 1993;48:55–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Messadi DV. Oral and nonoral sources of halitosis. J Calif Dent Assoc. 1997;25:127–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Almas K, Al-Hawish A, Al-Khamis W. Oral hygiene practices, smoking habit, and self-perceived oral malodor among dental students. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2003;15:77–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.ADA Council on Scientific Affairs. Oral malodour. J Am Dent Assoc. 2003;134:209–214. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Porter SR, Scully C. Oral malodour halitosis. BMJ. 2006;333:632–635. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38954.631968.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bosy A. Oral malodor: philosophical and practical aspects. J Can Dent Assoc. 1997;63:196–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rosenberg M, Kozlovsky A, Gelernter I, Cherniak O, Gabbay J, Baht R, Eli I. Self-estimation of oral malodor. J Dent Res. 1995;74:1577–1582. doi: 10.1177/00220345950740091201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pratibha PK, Bhat KM, Bhat GS. Oral malodor: a review of the literature. J Dent Hyg. 2006;80:8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Al-Ansari JM, Boodai H, Al-Sumait N, Al-Khabbaz AK, Al-Shammari KF, Salako N. Factors associated with self-reported halitosis in Kuwaiti patients. J Dent. 2006;34:444–449. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2005.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.al-Otaibi M. The miswak chewing stick and oral health. Studies on oral hygiene practices of urban Saudi Arabians. Swed Dent J Suppl. 2004;167:2–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.John M, Vandana KL. Detection and measurement of oral malodour in periodontitis patients. Indian J Dent Res. 2006;17:2–6. doi: 10.4103/0970-9290.29899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yaegaki K, Sanada K. Biochemical and clinical factors influencing oral malodor in periodontal patients. J Periodontol. 1992;63:783–789. doi: 10.1902/jop.1992.63.9.783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Roldán S, Herrera D, O'Connor A, González I, Sanz M. A combined therapeutic approach to manage oral halitosis: a 3-month prospective case series. J Periodontol. 2005;76:1025–1033. doi: 10.1902/jop.2005.76.6.1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Almas K, Al-Sanawi E, Al-Shahrani B. The effect of tongue scraper on mutans streptococci and lactobacilli in patients with caries and periodontal disease. Odontostomatol Trop. 2005;28:5–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Haas AN, Silveira EM, Rösing CK. Effect of tongue cleansing on morning oral malodour in periodontally healthy individuals. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2007;5:89–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Koshimune S, Awano S, Gohara K, Kurihara E, Ansai T, Takehara T. Low salivary flow and volatile sulfur compounds in mouth air. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2003;96:38–41. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(03)00162-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Signoretto C, Burlacchini G, Bianchi F, Cavalleri G, Canepari P. Differences in microbiological composition of saliva and dental plaque in subjects with different drinking habits. New Microbiol. 2006;29:293–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]