Abstract

Context

Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) in adolescents is common and impairing. Efficacious treatments have been developed, but little is known about longer term outcomes, including recurrence.

Objectives

To determine whether adolescents who responded to acute treatments, or who received the most efficacious acute treatment, would have lower recurrence rates, and to identify predictors of recovery and recurrence.

Design

Naturalistic follow-up study.

Setting

Twelve academic sites in the United States.

Participants

One hundred ninety-six adolescents (86 males and 110 females) randomized to one of four acute interventions (fluoxetine (FLX), cognitive behavior therapy (CBT), their combination (COMB), or placebo (PBO)) in the Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study (TADS) were followed for five years after study entry (44.6% of the original TADS sample).

Main Outcome Measure

Recovery was defined as absence of clinically significant MDD symptoms on the K-SADS-P/L interview for at least eight weeks, and recurrence as a new episode of MDD following recovery.

Results

Almost all participants (96.4%) recovered from their index episode of MDD during the follow-up period. Recovery by two years was significantly more likely for acute treatment responders (96.2%) than for partial or non-responders (79.1%) (p < .001), but was not associated with having received the most efficacious acute treatment (COMB). Of the 189 participants who recovered, 88 (46.6%) had a recurrence. Recurrence was not predicted by full acute treatment response or by original treatment. However, full or partial responders were less likely to have a recurrence (42.9%) than were non-responders (67.6%) (p = .03). Gender predicted recurrence (57.0% among females and 32.9% among males) (p = .024).

Conclusions

Almost all depressed adolescents recovered. However, recurrence occurs in almost half of recovered adolescents, with higher probability in females in this age range. Further research should identify and address the vulnerabilities to recurrence that are more common among young women.

Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) is one of the most prevalent psychiatric disorders among adolescents, with rates of approximately 5.9% among females and 4.6% among males.1 It is associated with functional impairment, risk of suicide and of adult depression.2,3,4 Thus, it is important to investigate not only the efficacy of adolescent MDD treatments, but also whether they reduce risk of subsequent negative outcomes, especially depression recurrence.

The episodic nature of adolescent MDD is evident across community and clinical samples. In community samples, approximately 75% of MDD episodes end within six to 15 months.5,6,7 However, recurrence rates reach 45% in six years.8 In clinical samples, recovery rates one year after treatment onset range from 81% to 98%,9,10 but recurrence rates range from 54% in three years among outpatients9 to over 60% in one year for inpatients.10

Treatment studies usually report outcomes of response (clinically significant improvement) and remission (no or very few remaining symptoms).11,12 Three clinical trials have also reported rates of recovery (maintenance of remission for an extended period) and recurrence (a new episode following recovery). Emslie and colleagues13 assessed 87 child and adolescent MDD outpatients one year after treatment with fluoxetine or placebo. Eighty-five percent had recovered, but 39% of recovered patients experienced a recurrence. Rates were not reported by initial randomized treatment. Clarke and colleagues14 followed 64 depressed adolescents treated with cognitive behavior therapy (CBT). Over two years, almost all recovered, but 22% of recovered adolescents experienced a recurrence. Birmaher and colleagues15 followed 107 depressed adolescents two years after treatment with one of three psychotherapies. Eighty percent recovered, with no differences among treatments. However, 30% of recovered adolescents had one and 8% had two recurrences. Thus, even effective treatments can be followed by recurrence rates of 30% to 40% within one to two years, with no treatment yet surpassing others in preventing recurrence.

In this study, we investigated recovery from and recurrence of MDD during an extended naturalistic follow-up of participants in the Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study (TADS). We first described recovery rates over five years from TADS baseline, and to facilitate comparison with previous research,15 tested predictors of recovery by two years. Second, we described recurrence rates over the five year period and tested predictors of recurrence. Third, we investigated long-term effects on recovery or recurrence of initial treatment and of acute response. Finally, because about 8% to 20% of depressed adolescents are at risk to develop bipolar disorder,9 we described the rate of this outcome in our sample.

TADS compared fluoxetine (FLX), CBT, and their combination (COMB), and included a placebo (PBO) condition. COMB was the most efficacious acute treatment.16 Active treatment groups did not differ in rates of sustained response (75% to 88%) or remission (55% to 60%) at nine months, following maintenance treatment,17,18 or remission (68%) one year later.19 Among adolescents randomized to PBO, followed by open treatment, 48% were in remission at nine months.20

To investigate longer-term recovery and recurrence we first identified baseline or post- acute treatment predictors found in three studies of recovery following a fluoxetine trial,13 recurrence following inpatient treatment,10 or recovery and recurrence following a psychotherapy trial.15 We included all predictors from these studies except psychotic features,10 an exclusion criterion in TADS. Second, we included variables that had predicted or moderated acute TADS outcome.21 Third, we included residual symptoms following acute TADS treatment, which had predicted non-remission after maintenance treatment.18 Finally, because of gender differences in MDD prevalence, we included gender. Potential predictors are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Potential Predictors of Recovery or Recurrence

| Baseline | End of Acute Treatment |

|---|---|

| Agea,c,f | |

| Gender | |

| Family incomed | |

| Minority ethnicityf | |

| Clinic referralg | |

| Interviewer-rated depressiona,b,d,f | Interviewer-rate depressionb |

| Self-reported depressionb,f | Self-reported depressionb |

| Residual MDD symptomse | |

| Index episode durationc | |

| Melancholic featuresc | |

| Global functioningc | Global functioningb |

| Suicidal ideationc,f | |

| Hopelessnessc | Hopelessnessb |

| Cognitive distortionsd | Cognitive distortionsd |

| Comorbid anxiety disorderc | |

| Number of comorbid disordersa,c | |

| Expectations for improvementc | |

| Parent-adolescent conflicta | Parent-adolescent conflictg |

Note.

predicted recovery following medication trial;13

predicted recovery following psychotherapy trial;15

predicted acute outcome in the Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study (TADS);21

moderated acute outcome in TADS;21

predicted remission after maintenance treatment in TADS;18

predicted recurrence following inpatient treatment;10

predicted recurrence following psychotherapy trial.15

Although it is not ethically possible to test long term treatment effects by withholding treatment from a control group, it is possible to compare groups who responded more or less successfully to acute treatment.22 We hypothesized that favorable response to acute treatment would predict higher rates of recovery and lower rates of recurrence. Following Birmaher15 we also tested the hypotheses that treatment with the most efficacious acute intervention would predict higher rates of recovery and lower rates of recurrence than treatment with other interventions.

Method

Relation of TADS to present study

TADS compared FLX, CBT, and COMB to one another across acute (12 weeks), continuation (6 weeks), and maintenance (18 weeks) treatment; and to placebo (PBO) acutely. Participants (N = 439) were randomized to FLX, CBT, COMB, or PBO. Following acute treatment, PBO partial responders, non-responders, or responders who relapsed, were offered their TADS treatment of choice. Following maintenance treatment, adolescents were followed openly for one year.19 The present study, Survey of Outcomes Following Treatment for Adolescent Depression (SOFTAD), was an open follow-up extending an additional three and one-half years after the TADS follow-up year. The TADS-SOFTAD period spanned 63 months (21 months of TADS and 42 months of SOFTAD), with diagnostic interviews administered according to the schedule shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Schedule of Diagnostic Interview Assessments During TADS and SOFTAD

| TADS Period | SOFTAD Period |

|---|---|

| Baseline | |

| Month 3 (end of Stage I) | |

| Month 9 (end of Stage III) | |

| Month 15 | |

| Month 21 (end of Stage IV) | |

| Month 27 | |

| Month 33 | |

| Month 39 | |

| Month 51 | |

| Month 63 |

Note. TADS = Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study; SOFTAD = Survey of Outcomes Following Treatment for Adolescent Depression.

All months are in time since TADS baseline.

The design, sample characteristics, and outcomes of TADS have been described previously.16,23,24 Treatment response was defined as an independent evaluator rating of 1 (very much improved) or 2 (much improved), partial response as a 3 (minimally improved), and non-response as 4 or higher, on the seven-point Clinical Global Impressions-Improvement scale (CGI-I).25 During TADS, remission was defined as a normalized score (< 29) on the Children’s Depression Rating Scale-Revised (CDRS-R).26

Participants in SOFTAD were recruited from among all 439 adolescents who had been randomized in TADS. TADS participants were recruited between spring 2000 and summer 2003. SOFTAD recruitment occurred from spring 2004 to winter 2008. Recruitment involved: 1) re-contacting TADS early completers and dropouts; and 2) after spring 2004, asking TADS completers to participate. For minors, written parental consent and adolescent assent were obtained. For adults, written consent and that of their parents was obtained, since parents completed some measures. The Duke and site IRB’s approved this study.

Initial SOFTAD assessment optimally occurred 27 months after TADS baseline, but participants began assessments at whatever assessment point corresponded most closely to the time of their recruitment. At most, participants could complete seven SOFTAD assessments at six month intervals, of which five included diagnostic interviews.

SOFTAD Participants

SOFTAD participants were 196 adolescents (44.6% of youths randomized in TADS), representing 12 of 13 TADS sites. One site was unable to recruit participants. The sample included 110 females (56%). Mean age at SOFTAD entry was 18 years (SD = 1.8 years; range = 14 to 22). The sample was 79% Caucasian, 9% Latino, 8% African-American, and 4% other ethnicity. Point of entry into SOFTAD, in months since TADS baseline, was as follows: Month 27 (33%); Month 33 (22%); Month 39 (14%); Month 45 (11%); Month 51 (10%); Month 57 (8%); and Month 63 (2%). The modal number of completed SOFTAD assessments was 5, with a mean of 3.5 (SD = 1.5).

Criterion Measures

Diagnoses

The Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia-Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-P/L)27 was administered at five SOFTAD assessment points (Table 2). The K-SADS was used in TADS and by Birmaher et al.,15 and assessed mood, anxiety, behavior, eating, substance use, psychotic, and tic disorders, using DSM-IV criteria,28 for the time since the last TADS or SOFTAD assessment and current MDD.

Episodes of Major Depression

When the K-SADS-P/L indicated MDD at any point since the last interview, the interviewer inquired about episode onset (time when participant met full diagnostic criteria) and, if relevant offset (time when the participant had no remaining clinically significant MDD symptoms for at least two weeks). We used the absence of MDD symptoms on the K-SADS-P/L rather than a normalized CDRS-R score to define remission in SOFTAD, to facilitate comparison with previous research15 and because participants exceeded CDRS-R age limits.

Definition of Recovery and Recurrence

Consistent with adult criteria and prior adolescent research,15,29 we defined recovery as remission lasting at least eight weeks, with the exception noted below for recovery during the TADS period. Following recovery, time of MDD recurrence was estimated as the month when five or more symptoms again became present.

Although SOFTAD interviews inquired about the time since the preceding TADS or SOFTAD interview, TADS interviews had only inquired about current symptoms. To deal with this limitation we assumed that an index episode of MDD during the TADS period was in remission if no symptoms were reported on a K-SADS-P/L assessment and in recovery if no symptoms were reported at two consecutive TADS assessments.

Interviewer training

SOFTAD evaluators met the same education and experience criteria as TADS evaluators. Certification following didactic training required: 1) rating a videotaped standard patient interview, with agreement on presence or absence of MDD, 80% agreement on the full MDD criterion set, and agreement on other classes of disorders (e.g., anxiety disorder); 2) rating a site-based interview, subsequently rated at the coordinating center with acceptable reliability, using these same criteria.

Evaluators had monthly conference calls and annually rated a standard patient interview. On these there was complete agreement between evaluators and coordinating center ratings for diagnosis of MDD since the last interview, 96% agreement on current MDD; 91% of evaluator ratings exceeded 80% agreement on diagnostic criteria.

Predictors of Recovery or Recurrence

The following predictors of recovery and recurrence were measured at TADS baseline:

Age, Ethnicity, Gender, Family Income, and Referral Source

These were reported by participants or parents. Income was dichotomized at $75,000 and ethnicity as Caucasian or non-Caucasian for comparison with previous findings.10,21

Duration of Index Episode and Depression Severity

An independent evaluator estimated the duration of the index Major Depressive Episode (MDE) and completed the CDRS-R26 for severity. Adolescents completed the Reynolds Adolescent Depression Scale (RADS).30

Global Functioning

The evaluator assigned a rating on the Children’s Global Assessment Scale (CGAS).31

Suicidal Ideation

Adolescents completed the Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire-Jr (SIQ-Jr).32

Melancholic Features

This index included five CDRS-R items: anhedonia, insomnia, appetite disturbance, guilt, and psychomotor retardation.

Comorbidity

The K-SADS-P/L yielded comorbid diagnoses.

Hopelessness, Cognitive Distortions, and Treatment Expectancy

Adolescents completed the Beck Hopelessness Scale (BHS),33 the Children’s Negative Cognitive Errors Questionnaire (CNCEQ),34 and rated their expectations for improvement with FLX, CBT, or COMB.

Parent-Adolescent Conflict

Adolescents and parents completed the Conflict Behavior Questionnaire (CBQ).35

The following predictors of recovery were assessed at the end of TADS acute treatment: CDRS-R, RADS, CNCEQ, BHS, CGAS, residual K-SADS MDD symptoms, and CBQ scores, with the latter two also investigated as predictors of recurrence.

Treatment During SOFTAD

At each SOFTAD assessment, participants reported if they had received psychotherapy or anti-depressant medication.

Statistical Analysis

Baseline characteristics of TADS participants who enrolled in SOFTAD (N=196) were compared to those who did not (N=243) using General Linear Models (GLM) for continuous measures and Chi-Square for binary outcomes. Fisher’s Exact Test or non-parametric Median Test were alternatively employed as needed.

Because recovery during the TADS period was estimated on the basis of two consecutive symptom-free interviews, separated by three or six months, and not, as in SOFTAD, on the basis of a specific month of recovery, we reported cumulative percentage of recovered subjects in six month intervals from TADS baseline. Participants were subdivided into three groups: (1) persistent depression (baseline MDE never resolved); (2) recovery from baseline MDE without recurrence; and (3) recovery with recurrence. For comparison with previous research,15 we examined recovery by two-year follow-up, testing its predictors with logistic regression. Among those who recovered at any point, we examined predictors of recurrence over the 63-month period using logistic regression, and reported mean and median time from recovery to recurrence.

All analyses were conducted with SAS 9.2. Non-directional hypotheses were tested, with the significance level set at 0.05 for each test. The alpha was not adjusted for multiple outcomes or tests due to the exploratory nature of the investigation.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

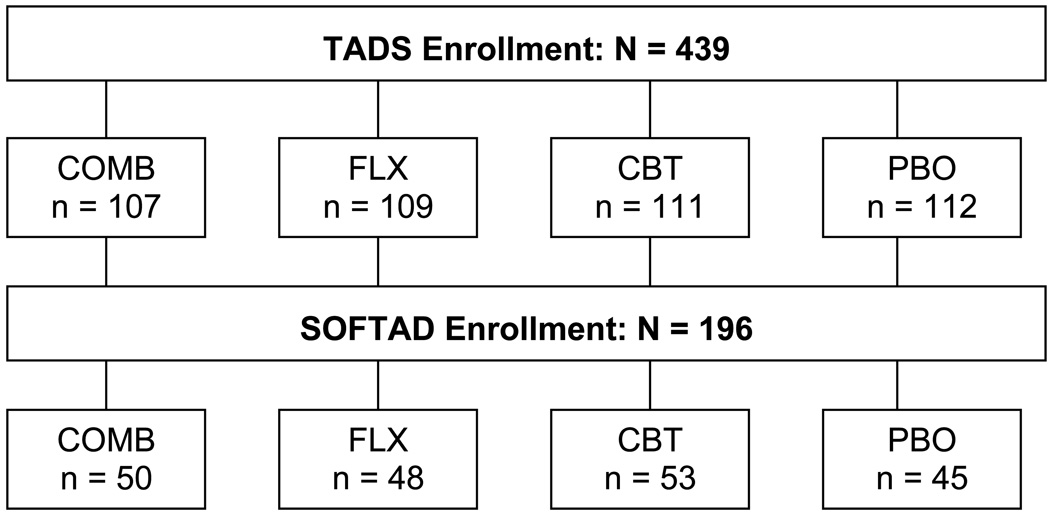

To determine whether SOFTAD participants represented the full TADS sample, we compared them to TADS participants not in SOFTAD on the variables related to hypothesis testing. Participants and non-participants did not differ on percentage of acute treatment responders (53.6% versus 51.0%, Chi Square (1) = 0.28, p = 0.60) or initial treatment condition (Chi Square (3) = 1.54, p = 0.67). Figure 1 depicts the number of SOFTAD participants from each condition.

Figure 1.

SOFTAD Patient Flow

Demographic and clinical comparisons are shown in Table 3. There were few differences. SOFTAD participants were younger (p < .01), included fewer minority adolescents (p < .05), were more likely in their initial episode, had fewer total comorbid disorders, and fewer anxiety disorders (both p < .05).

Table 3.

TADS Baseline Characteristics of SOFTAD Participants and Non-Participants

| Participants | Non-Participants | Statistic | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 196 | N = 243 | |||

| Female (%) | 56.1% | 53.1% | 0.401 | 0.53 |

| Age (yrs.), M (SD) | 14.3 (1.5) | 14.7 (1.6) | 7.782 | 0.006 |

| Minority (%) | 21.5% | 30.0% | 4.161 | 0.04 |

| High Income (%) | 23.7% | 26.7% | 0.461 | 0.50 |

| Clinic Referral (%) | 29.6% | 35.4% | 1.661 | 0.20 |

| Duration (wks), Mdn | 37 | 42 | −0.703 | 0.48 |

| First MDE (%) | 90.2% | 82.6% | 5.001 | 0.02 |

| CDRS-R, M (SD) | 59.6 (10.2) | 60.6 (10.5) | 1.052 | 0.31 |

| RADS, M (SD) | 78.5 (15.4) | 79.9 (13.4) | 1.002 | 0.32 |

| SIQ-Jr, Mdn | 15.0 | 17.5 | −1.573 | 0.12 |

| CGAS, M (SD) | 50.2 (7.8) | 49.2 (7.2) | 2.062 | 0.15 |

| Comorbid Diagnoses, Mdn | 0.0 | 1.0 | −2.003 | 0.04 |

| Dysthymia (%) | 7.7% | 12.8% | 2.951 | 0.08 |

| SUD (%) | 1.0% | 2.1% | na4 | 0.47 |

| Anxiety (%) | 22.5% | 31.4% | 4.371 | 0.04 |

| DBD (%) | 21.9% | 24.7% | 0.461 | 0.50 |

| OCD/tic (%) | 2.6% | 2.9% | 0.041 | 0.83 |

Note. TADS = Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study; SOFTAD = Survey of Outcomes Following Treatment for Adolescent Depression; High Income = >$75,000/year; Duration = Duration at TADS baseline of index Major Depressive Episode; Mdn = Median; MDE = Major Depressive Episode; CDRS-R = Children’s Depression Rating Scale-Revised; RADS = Reynolds Adolescent Depression Scale; SIQ-Jr = Suicide Ideation Questionnaire-Junior High Version; CGAS = Children’s Global Assessment Scale; SUD = Substance Use Disorder; DBD = Disruptive Behavior Disorder; OCD/tic = Obsessive Compulsive or Tic Disorder.

Chi Square

General Linear Model F, with degrees of freedom of (1, 437) or, for RADS (1, 426)

Median Test z-value

Fisher’s Exact Test

Recovery

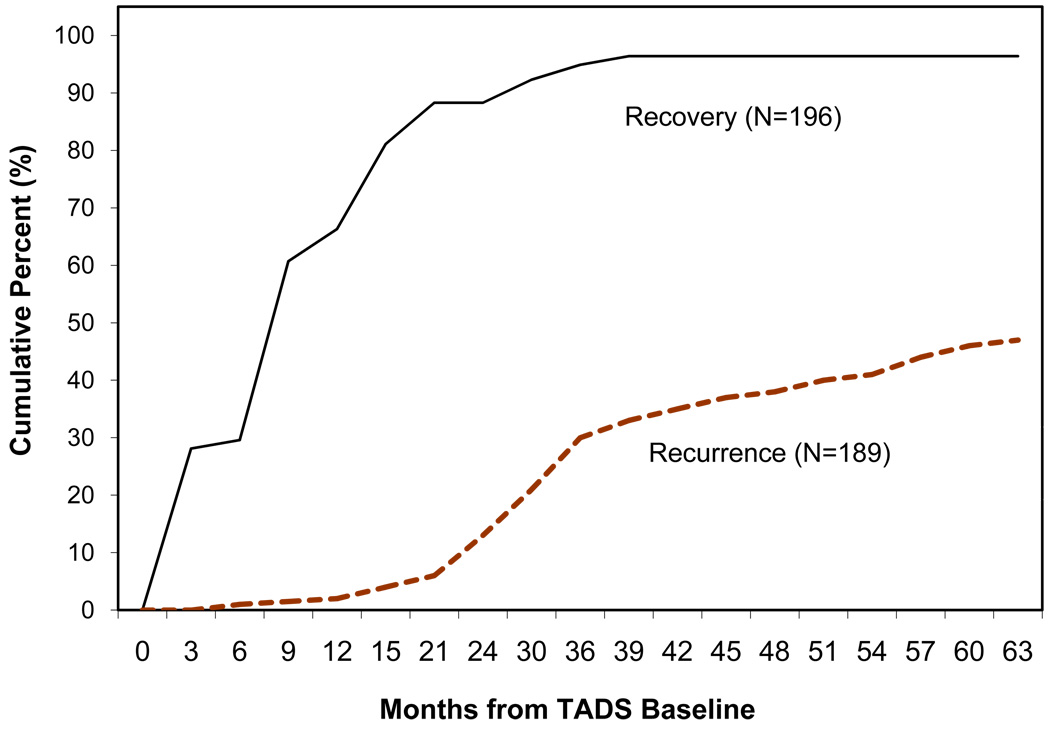

The vast majority of SOFTAD participants recovered from their index MDE during the 63 months, as shown in Figure 2. Specifically, 189 (96.4%) recovered; seven (3.6%) did not. Cumulative recovery rate was as follows: 29.6% (six months); 66.3% (12 months); 84.7% (18 months); 88.3% (24 months); 92.3% (30 months); 94.8% (36 months); 96.4% (42 months). Among the 189 adolescents who recovered, 68.8% had done so by one year after baseline, and 91.5% within two years.

Figure 2.

Cumulative Recovery and Recurrence Rates

Prediction of Recovery by Two Years

As hypothesized, recovery by two years was significantly more likely for those who were acute treatment responders (96.2%) than for others (79.1%) (Chi Square (1) = 11.02, p < .001). However, it was not associated with COMB, or any particular treatment, or any baseline variables. Among post-acute treatment variables, recovery was significantly predicted by less severe evaluator-rated depression (CDRS-R; Chi Square (1) = 12.54, p < 0.001), and higher global functioning (CGAS; Chi Square (1) = 5.48, p = 0.019). There were trends for lower parent-reported conflict (CBQ; Chi Square (1) = 3.70, p = 0.054) and more cognitive distortions (CNCEQ; Chi Square (1) = 3.00, p = 0.084) to predict recovery by year two. Self-reported depression (RADS), hopelessness (BHS), and adolescent-reported conflict (CBQ) with mother or father were not significant predictors (all p’s > .15).

For 186 participants with complete K-SADS symptom ratings after acute treatment, any of seven MDD symptoms (excluding psychomotor or concentration disturbance) was associated with lower probability of recovery in two years. With all seven in a multivariable logistic regression, the significant predictors were appetite/weight disturbance (Chi Square (1) = 1.13, p = .029) and sleep disturbance (Chi Square (1) = 1.11, p = .033).

Recurrence

Of 189 participants who recovered, 101 (53.4%) remained well throughout the SOFTAD period, and 88 (46.6%) had MDD recurrence. Most had one (n = 74), but 12 had two, and two had three recurrences. Figure 2 shows rate of first recurrence across time. Among all recovered participants, cumulative recurrence rates for years one through four were 1.6%, 12.2%, 29.6%, and 38.1%. One year after TADS baseline, only 3.4% of the 88 recurrences had occurred. Corresponding rates for two, three and four years were 26.1%, 63.6%, and 81.8%, respectively.

For those with recurrence, mean time from recovery to first recurrence was 22.3 months (SD = 13.9 months; median = 20.3 months). Time from recovery to recurrence ranged from two to 55 months, with cumulative rates as follows: 12.5% (6 months); 26.1% (12 months); 40.9% (18 months); 61.3% (24 months); 77.3% (30 months); 84.9% (36 months).

Prediction of Recurrence

Within the SOFTAD sample of 196, 105 (53.6%) had been full responders to acute treatment, whereas 91 (46.4%) had not (54 partial responders and 37 non-responders). For the 189 who recovered, the full response rate was 55.6% and the partial/non-response rate was 44.4%.

Contrary to hypothesis, the recurrence rate for full responders (45.7%) was not significantly lower than for others (47.6%) (Chi Square (1) = .07, p = .79). We explored whether the combined group of full and partial responders had a lower recurrence rate than non-responders. Recurrence rates were 42.9% for full or partial responders and 67.6% for non-responders, a significant difference (Chi Square (1) = 4.7, p = .03).

Contrary to hypothesis, the recurrence rate for COMB participants (49.0%) did not differ from that of others (45.7%) (Chi Square (1) = 0.16, p = 0.69). There were no treatment condition differences in recurrence rates (Chi Square (3) = 1.91, p = 0.59).

Additional Predictors of Recurrence

In individual regression models, four baseline variables predicted recurrence: gender (Chi Square (1) = 10.58, p = .001), self-reported depression (RADS; Chi Square (1) = 6.16, p = .013), suicidal ideation (SIQ-Jr; Chi Square (1) = 6.88, p = .009), and comorbid anxiety disorder (Chi Square (1) = 4.98, p = .026). Among females, 57.0% experienced recurrence, compared to 32.9% of males. Among those with anxiety disorder, 61.9% experienced recurrence compared to 42.2% of others. Participants with recurrence had higher RADS and SIQ-Jr scores (RADS M = 81.5, SD = 14.6 versus M = 75.7, SD = 15.8; SIQ-Jr M = 25.4, SD = 21.1 versus M = 17.4, SD = 18.4).

In a multivariable regression including these four predictors, only female gender remained significant (Chi Square (1) = 5.04, p = .024). Anxiety disorder approached significance (Chi Square (1) = 3.35, p = .067).

Bipolar Disorder

The emergence of bipolar disorder was relatively rare. Twelve participants (6.1%; 3 males, 9 females) were diagnosed with bipolar I (n = 5), bipolar II (n = 4) or, if duration was one day below criterion, bipolar NOS (n = 3). Bipolar outcome was unrelated to treatment condition, but most (n = 9) had not responded to acute treatment. One never recovered from the index MDE; the other 11 recovered but had recurrence. In each case bipolar disorder emerged after the end of the TADS period, at a mean age of 18.0 years (SD = 1.4 years). Given the small number, we did not conduct further statistical comparisons.

Treatment During SOFTAD

During SOFTAD, 83 participants (42%) received psychotherapy, and 88 (45%) received anti-depressant medication, each unrelated to TADS treatment condition (p > .05). Each was more likely among participants who had not recovered by two years (psychotherapy, Chi-Square (1) = 5.23, p = .02; medication, Chi Square (1) = 4.13, p = .04), and among those with recurrence, than among those with recovery and no recurrence (psychotherapy, Chi Square (1) = 13.77, p < .001; medication, Chi Square (1) = 16.00, p < .001).

Discussion

We followed 196 adolescent participants in TADS, the largest treatment follow-up sample of depressed adolescents to date. Rate of recovery from the index MDE over five years from TADS baseline was very high (96.4%), and 88.3% recovered within two years. As hypothesized, full acute treatment response was associated with recovery by two years, as were other post-acute treatment variables: less severe depression, absence of sleep or appetite disturbance, and better functioning. Contrary to hypothesis, treatment with COMB did not predict recovery in two years.

Slightly under half of recovered adolescents experienced a recurrence by five years post-baseline (46.6%). Contrary to hypotheses, neither full response to acute treatment nor treatment with COMB reduced risk of recurrence. However, acute treatment non-responders were more likely to experience recurrence than full and partial responders. Females were significantly more likely to have a recurrence than males.

The SOFTAD two year recovery rate of 88% is comparable to the previously reported rate of 80%.15 Comparisons with previous TADS findings,18,19 indicate that remission rates increase, and progress toward recovery continues after treatment ends, consistent with other studies.13,15 This is the second study to indicate that longer-term recovery rates are not superior for adolescents receiving the most efficacious acute treatment.15 Such findings may be attributed to the episodic nature of depressive disorder, and limited variance in two year recovery as a comparative index.

The SOFTAD recurrence rate reached 30% three years after baseline, whereas it had reached this rate two years after a previous psychotherapy trial.15 Although sample differences cannot be ruled out, it is possible that incorporating continuation and maintenance treatment within TADS slowed the pace of recurrence. The lower rate of recurrence in TADS is consistent with the previous finding that TADS treatment gains were generally maintained during the first year of follow-up.19 Unfortunately, no treatment has yet been identified that reduces adolescent recurrence rates.

The most robust predictor of recurrence was female gender. Females are more likely than males to experience MDD after approximately age 14,36 but to our knowledge this is the first study documenting higher recurrence rates among treated adolescent females. Adult studies do not show a gender difference in recurrence.37 One adolescent community study did show such a difference38 from ages 19–23. This age range overlaps ours, suggesting that female vulnerability to recurrence may be age related. Factors implicated as potential causes of higher depression rates among post-pubertal women include sex steroids,39 chronic environmental stressors, low perceived mastery and ruminative response style.40 Further research should investigate whether more frequent MDD recurrence among young women is confirmed and if so, what variables are associated with it.

Anxiety disorder was an individual predictor of recurrence. Anxiety disorders were more frequent among females (28%) than among males (15%) (Chi Square = 4.73, p = .03), likely accounting for the elimination of anxiety disorder as a predictor when considering gender simultaneously. Anxiety disorders also predicted poorer acute outcome in TADS.21 In depressed adults, anxiety mitigates the effectiveness of anti-depressant treatment,41 and slows response time to CBT.42 These findings suggest that adolescent MDD with anxiety requires further treatment development.

The rate of bipolar outcome in our sample was lower than in adolescent inpatient samples, but similar to rates found among outpatients.9 Our rate likely reflects exclusion from TADS of participants for whom a placebo-controlled outpatient study was inappropriate (e.g., those with psychotic depression or acute suicidal risk).

Clinical Implications

Our results reinforce the importance of modifying an acute treatment that leads to partial or non-response, since these were associated with less likelihood of recovery in two years. A study of adolescent SSRI non-responders showed that augmentation with CBT improved response rates.43 To our knowledge, no parallel study has been completed investigating medication augmentation for incomplete CBT response, but treatment algorithms recommend such augmentation.44 The finding that recurrence rates increased significantly from two to three years after baseline suggests that recurrence prevention efforts, such as symptom or medication monitoring or CBT booster sessions, may be of value beyond the maintenance period included in TADS.

Limitations

The most significant limitation of this study is that slightly less than half of TADS participants took part. This likely reflects the difficulty maintaining a sample of adolescents during a period when many are moving away from home. Indeed, SOFTAD participants were somewhat younger than non-participants. Nevertheless, they did not differ on most measures, including depression characteristics, initial treatment, acute treatment response rates, or gender. Participants had fewer anxiety disorders, suggesting that recurrence rates may have been higher if all TADS adolescents had participated.

Two other limitations should be noted. First, there was not a no-treatment condition in TADS. Second, most PBO cases eventually received a TADS treatment,20 and access to treatment was not controlled during SOFTAD. Thus, findings do not reflect the naturalistic course of untreated depression. In a separate report we will describe participants’ treatment utilization in more detail.

In summary, all predictors of recovery by two years were associated with clinical status after acute treatment. Female gender was the most robust predictor of recurrence, indicating the importance of understanding and reducing the vulnerabilities of female adolescents to recurrent episodes.

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to Benedetto Vitiello, M.D. who coordinated administration of SOFTAD at NIMH. We thank participants and the site staff who recruited them, including Margaret Price, Stephanie Frank, and Sue Baab. We acknowledge the many contributions of the late Dr. Elizabeth Weller, a dedicated clinical scientist.

Dr. Curry had access to all data and is responsible for its integrity and data analyses.

Funding/Support: This study was funded by grant R01 MH070494 from the National Institute of Mental Health to the first author.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: Drs. Curry and Wells provide training through the REACH Institute. Dr. Kratochvil receives grant support from Lilly, Abbott, Somerset, consults for Lilly, Abbott, Neuroscience Education, AstraZeneca, Pfizer. Dr. Emslie consults for BioBehavioral Diagnostics, Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer, Wyeth, is a speaker for Forest, and receives research funding from Somerset. Dr. Walkup receives research support from Pfizer, Lilly, Abbott, and royalties from Oxford and Guilford Press. Dr. March owns equity in MedAvante, consults for Pfizer, Wyeth, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Johnson & Johnson, is an advisor for Pfizer, Lilly, Scion, Psymetrix, receives research support from Pfizer, Lilly, royalties from MultiHealth Systems, Guilford, and Oxford Press. Other authors have no financial interests to report.

Contributor Information

John Curry, Duke University Medical Center and Clinical Research Institute

Susan Silva, Duke University Medical Center and Clinical Research Institute

Paul Rohde, Oregon Research Institute

Golda Ginsburg, Johns Hopkins Medical Institute

Christopher Kratochvil, University of Nebraska Medical Center

Anne Simons, University of Oregon

Jerry Kirchner, Duke Clinical Research Institute

Diane May, University of Nebraska Medical Center

Betsy Kennard, University of Texas Southwestern

Taryn Mayes, University of Texas Southwestern

Norah Feeny, Case Western Reserve University

Anne Marie Albano, Columbia University Medical Center

Sarah Lavanier, Cincinnati Children’s Medical Center

Mark Reinecke, Northwestern University

Rachel Jacobs, Northwestern University

Emily Becker-Weidman, Northwestern University.

Elizabeth Weller, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia

Graham Emslie, University of Texas Southwestern

John Walkup, Johns Hopkins Medical Institute

Elizabeth Kastelic, Johns Hopkins Medical Institute

Barbara Burns, Duke University Medical Center

Karen Wells, Duke University Medical Center

John March, Duke Clinical Research Institute

References

- 1.Costello EJ, Erkanli A, Angold A. Is there an epidemic of child or adolescent depression? J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2006;47(12):1263–1271. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01682.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Birmaher B, Bridge JA, Williamson DE, Brent DA, Dahl RE, Axelson DA, Dorn LD, Ryan ND. Psychosocial functioning in youths at high risk to develop major depressive disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43(7):839–846. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000128787.88201.1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gould MS, King R, Greenwald S, Fisher P, Schwab-Stone M, Kramer R, Flisher AJ, Goodman S, Canino G, Shaffer D. Psychopathology associated with suicidal ideation and attempts among children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998;37(9):915–923. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199809000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lewinsohn PM, Rohde P, Klein DN, Seeley JR. Natural course of adolescent major depressive disorder: I. Continuity into young adulthood. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1999;38(1):56–63. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199901000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Keller MB, Beardslee W, Lavori PW, Wunder J, Drs DL, Samuelson H. Course of major depression in non-referred adolescents: A retrospective study. J Affect Disord. 1988;15(3):235–243. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(88)90021-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Essau CA. Course and outcome of major depressive disorder in non-referred adolescents. J Affect Disord. 2007;99(1–3):191–201. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lewinsohn PM, Clarke GN, Seeley JR, Rohde P. Major depression in community adolescents: Age at onset, episode duration, and time to recurrence. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1994;33(6):809–818. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199407000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lewinsohn PM, Rohde P, Klein DN, Seeley JR. Natural course of adolescent major depressive disorder: I. continuity into young adulthood. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1999;38(1):56–63. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199901000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kovacs M. Presentation and course of major depressive disorder during childhood and later years of the life span. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1996;35(6):705–715. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199606000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Emslie GJ, Rush AJ, Weinberg WA, Gullion CM, Rintelmann J, Hughes CW. Recurrence of major depressive disorder in hospitalized children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36(6):785–792. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199706000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brent DA, Holder D, Kolko D, Birmaher B, Baugher M, Roth C, Iyengar S, Johnson BA. A clinical psychotherapy trial for adolescent depression comparing cognitive, family, and supportive treatments. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54:877–885. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830210125017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Emslie GJ, Rush J, Weinberg WA, Kowatch RA, Hughes CW, Carmody T, Rintelmann J. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of fluoxetine in children and adolescents with depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54:1030–1037. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830230069010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Emslie GJ, Rush AJ, Weinberg WA, Kowatch RA, Carmody T, Mayes TL. Fluoxetine in child and adolescent depression: Acute and maintenance treatment. Depress Anxiety. 1998;7(1):32–39. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1520-6394(1998)7:1<32::aid-da4>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clarke GN, Rohde P, Lewinsohn PM, Hops H, Seeley JR. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of adolescent depression: Efficacy of acute group treatment and booster sessions. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1999;38(3):272–279. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199903000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Birmaher B, Brent DA, Kolko D, Baugher M, Bridge J, Holder D, Iyengar S, Ulloa RE. Clinical outcomes after short-term psychotherapy for adolescents with major depressive disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57(1):29–36. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.March J, Silva S, Petrycki S, Curry J, Wells K, Fairbank J, Burns B, Domino M, McNulty S, Vitiello B, Severe J Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study (TADS) Team. Fluoxetine, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and their combination for adolescents with depression. JAMA. 2004;292(7):807–820. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.7.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rohde P, Silva SG, Tonev ST, Kennard BD, Vitiello B, Kratochvil CJ, Reinecke MA, Curry JF, Simons AD, March JS. Achievement and maintenance of sustained response during TADS continuation and maintenance therapy. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65(4):447–455. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.4.447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kennard BD, Silva SG, Tonev S, Rohde P, Hughes JL, Vitiello B, Kratochvil CJ, Curry JF, Emslie GJ, Reinecke MR, March JS. Remission and recovery in the Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study (TADS): Acute and long-term outcomes. J Amer Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48(2):186–195. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e31819176f9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.March J, Silva S, Curry J, Wells K, Fairbank J, Burns B, Domino M, Vitiello B, Severe J Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study (TADS) Team. The Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study (TADS): Outcomes over 1 year of naturalistic follow-up. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(10):1141–1149. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.08111620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kennard BD, Silva SG, Mayes TL, Rohde P, Hughes JL, Vitiello B, Kratochvil CJ, Curry JF, Emslie GJ, Reinecke MR, March JS. Assessment of safety and long-term outcomes of initial treatment with placebo in TADS. Amer J Psychiatry. 2009;166(3):337–344. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08040487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Curry J, Rohde P, Simons A, Silva S, Vitiello B, Kratochvil C, Reinecke M, Feeny N, Wells K, Pathak S, Weller E, Rosenberg D, Kennard B, Robins M, Ginsburg G, March J TADS Team. Predictors and moderators of acute outcome in the Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study (TADS) J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45(12):1427–1439. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000240838.78984.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kendall PC, Kessler RC. The impact of childhood psychopathology interventions on subsequent substance abuse: Policy implications, comments, and recommendations. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2002;70(6):1303–1306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study (TADS) Team. The treatment for adolescents with depression study (TADS): Demographic and clinical characteristics. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2005;44(1):28–40. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000145807.09027.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.March JS, Silva S, Petrycki S, Curry J, Wells K, Fairbank J, Burns B, Domino M, McNulty S, Vitiello B, Severe J Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study (TADS) Team. The treatment for adolescents with depression study (TADS): Long-term effectiveness and safety outcomes. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(10):1132–1143. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.10.1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guy W. ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 1976. DHEW Publication ABM 76-388. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Poznanski E, Mokros H. Children’s Depression Rating Scale-Revised Manual. Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, Rao U, Flynn C, Moreci P, Williamson D, Ryab N. Schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-age children-Present and lifetime version (K-SADS-PL): Initial reliability and validity data. J Am Acad Chil Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36(7):980–988. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition-Text Revision. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Frank E, Prien RF, Jarret RB, Keller MB, Kupfer DJ, Lavori PW, Rush AJ, Weissman MM. Conceptualization and rationale for consensus definitions of terms in major depressive disorder: remission, recovery, relapse, and recurrence. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991;48:851–855. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810330075011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reynolds W. Professional manual for the Reynolds Adolescent Depression Scale. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shaffer D, Gould MS, Brasic J, Ambrosini P, Fischer P, Bird H, Aluwahlia S. A children’s global assessment scale (CGAS) Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1983;40(11):1228–1231. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1983.01790100074010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reynolds W. Professional manual for the Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Beck AT, Steer RA. Manual for the Beck Hopelessness Scale. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leitenberg H, Yost LW, Carroll-Wilson M. Negative cognitive errors in children. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1986;54(4):528–536. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.54.4.528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Prinz RJ. Doctoral dissertation. Stony Brook: State University of New York; 1977. The assessment of parent-adolescent relations: Discriminating distressed and non-distressed dyads. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wade TJ, Cairney J, Pevalin DJ. Emergence of gender differences in depression during adolescence: National panel results from three countries. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41(2):190–198. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200202000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hasin DS, Goodwin RD, Stinson FS, Grant BF. Epidemiology of major depressive disorder: Results from the National Epidemiolog Survey on Alcoholism and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(10):1097–1106. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.10.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lewinsohn PM, Rohde P, Seeley JR, Klein DN, Gotlib IH. Natural course of adolescent major depressive disorder in a community sample: Predictors of recurrence in young adults. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(10):1584–1591. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.10.1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Angold A. Sex and developmental psychopathology. In: Hudziak JJ, editor. Developmental psychopathology and wellness: Genetic and environmental influences. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2008. pp. 109–138. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nolen-Hoeksema S, Larson J, Grayson C. Explaining the gender difference in depressive symptoms. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1999;77(5):1061–1072. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.77.5.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Clayton PJ, Grove WM, Coryell W, Keller M, Hirschfeld R, Fawcett J. Follow-up and family study of anxious depression. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148(11):1512–1517. doi: 10.1176/ajp.148.11.1512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brown C, Schulberg HC, Madonia MJ, Shear MK, Houck PR. Treatment outcomes for primary care patients with major depression and lifetime anxiety disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153(10):1293–1300. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.10.1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brent D, Emslie G, Clarke G, Wagner KD, Asarnow JR, Keller M, Vitiello B, Ritz L, Iyengar S, Ahebe K, Birmaher B, Ryan N, Kennard B, Hughes C, DeBar L, McCracken J, Strober M, Suddath R, Spirito A, Leonard H, Melhem N, Porta G, Onorato M, Zelazny J. Switching to another SSRI or to venlafaxine with or without cognitive behavioral therapy for adolescents with SSRI-resistant depression: The TORDIA randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;299(8):901–913. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.8.901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hughes CW, Emslie GJ, Crimson L, Posner K, Birmaher B, Ryan N, Jensen P, Curry J, Vitiello B, Lopez M, Shon SP, Pliszka SR, Trivedi MH the Texas Consensus Conference Panel on Medication Treatment of Childhood Major Depressive Disorder. Texas children’s medication algorithm project: Update from Texas consensus conference panel on medication treatment of childhood major depressive disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46(6):667–686. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e31804a859b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]