Abstract

Our laboratory has recently reported [Horn, J, Lopez, I, Miller, M and Gomez-Cambronero (2005) Biochem Biophys Res Comm 332, 58–67] that the enzyme phospholipase D2 (PLD2) exists as a ternary complex with PTP1b and Grb2. Here, we establish the mechanistic underpinnings of the PLD2/Grb2 association. We have identified residues Y169 and Y179 in the PLD2 protein as being essential for the Grb2 interaction. We present evidence indicating that Y169 and Y179 are located within two consensus sites in PLD2 that mediate an SH2 interaction with Grb2. This was demonstrated with a SH2-deficient GSTGrb2 R86K mutant that failed to pull down PLD2 in vitro. In order to elucidate the functions of the two neighboring tyrosines, we created a new class of deletion and point mutants in PLD2. Phenylalanine replacement of Y169 (PLD2 Y169F) or Y179 (PLD2 Y179F) reduced Grb2 binding while simultaneous mutation completely abolished it. The role of the two binding sites on PLD2 was found to be functionally non-equivalent: Y169 serves to modulate the activity of the enzyme, while Y179 regulates total tyrosine phosphorylation of the protein. Interestingly, binding of Grb2 to PLD2 occurs irrespectively of lipase activity, since Grb2 binds to catalytically inactive PLD2 mutants. Finally, PLD2 residues Y169 and Y179 are necessary for the recruitment of Sos, but only over expression of the PLD2 Y179F mutant resulted in increased Ras activity, p44/42Erk phosphorylation and enhanced DNA synthesis. Since Y169 remains able to modulate enzyme activity and is capable of binding to Grb2 in the PLD2 Y179F mutant, we propose that Y169 is kept under negative regulation by Y179. When this is released, Y169 mediates cellular proliferation through the Ras/MAPK pathway.

Keywords: PLD2, Tyrosyl phosphorylation, Sos

INTRODUCTION

Phospholipase D (PLD) catalyzes the hydrolysis of phosphatidylcholine to generate phosphatidic acid (PA), a second messenger, and choline (Cockcroft, 2001; Exton, 1998). Two main products of PLD genes have been described: PLD1 and PLD2 (Hammond et al., 1997; Lopez et al., 1998; Park et al., 1997; Sung et al., 1999), as well as their regulators (Powner & Wakelam, 2002). The expressed proteins contain two invariable sequences: HxK(x)4D(x)6GSxN (or HKD), that are responsible for their enzymatic activity; as well as several conserved regions, such as a PIP2 binding site, a plekstrin-homology (PH) domain and a phox (PX) domain (Park et al., 2000; Sung et al., 1999; Sung et al., 1997).

The PH domain of PLD2 associates with SH2/SH3-containing tyrosine kinases (Ahn et al., 2003; Choi et al., 2004) and the increase in total tyrosine phosphorylation of PLD2 correlates with an apparent increase in PLD activity (Choi et al., 2004). Whether total tyrosine phosphorylation of PLD2 and its high degree of basal activity are physiologically linked is subject to intense investigation (Bourgoin & Grinstein, 1992).

Phosphotyrosine motifs serve as docking sites for recruitment of SH2-domain containing proteins like the growth factor receptor bound protein 2 (Grb2) (Schlessinger, 1994). Grb2 is ubiquitously expressed and entirely composed of two SH3 domains and one central SH2 domain (Lowenstein et al., 1992). Grb2 binds phosphotyrosine-containing proteins through its SH2 domain, while the flanking SH3 domains interact with proline-rich motifs in signaling proteins. The most characterized of such interactions is the activation of the mitogenic Ras via direct interaction of the SH3 domains of Grb2 with the C-terminal proline-rich domain of the Ras guanine-nucleotide exchange factor, Sos, and the consequent stimulation of the MAPK cascade and cellular proliferation (Chardin et al., 1993; Egan et al., 1993).

As indicated previously by our laboratory, PLD2 exists as a complex with Grb2 and PTP1b (Horn et al., 2005). Here, we report that PLD2 residues Y169 and Y179 directly bind Grb2 and recruit Sos in vivo. The PLD2/Grb2/Sos interaction mediated by PLD2 Y169 and Y179 appears to be functionally not equivalent. Mutation of PLD2 residue Y169 abolishes PLD2 enzymatic activity, whereas Y179 regulates total tyrosine phosphorylation of the protein. Moreover, Y179 is negatively involved in cell proliferation through the Ras/MAPK pathway.

RESULTS

Preparation of mutant series

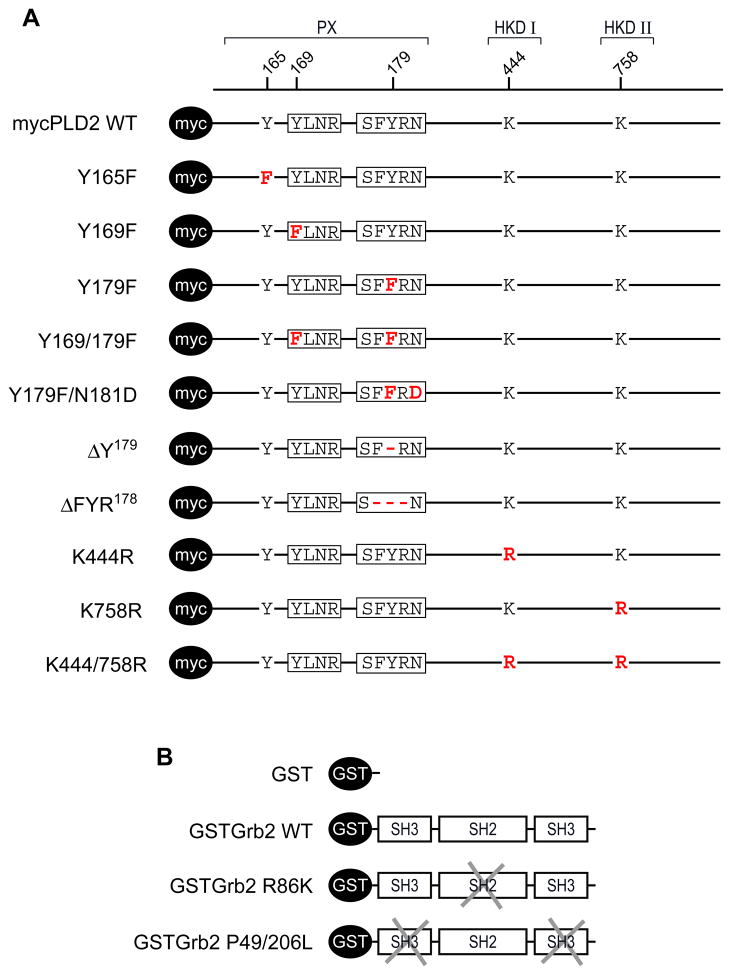

In experiments designed to analyze the interaction PLD2/Grb2, a series of expression plasmids were created. In the case of PLD2 mutants, (Fig. 1A), all the plasmids, which contain a myc tag, were transiently expressed in COS-7 followed by analysis of protein expression and lipase enzyme activity. In the case of Grb2 mutants, (Fig. 1B) all the plasmids, which contain a GST tag, were expressed in bacteria and the recombinant proteins purified in order to study the effect of binding of PLD2 in vitro.

Figure 1. Schematic non-scale representation of mycPLD2 and GSTGrb2 mutants.

(A) The amino acid residues involved in the creation of mutation and deletion series of mycPLD2 constructs are indicated in red together with their relative position (bar at the top). Also indicated are the PX domains and HKD domains. Boxed in the indicated PX domain of mycPLD2 are the sequences of interest used for these studies. (B) The typical SH3-SH2-SH3 domain structure of the fusion protein GSTGrb2 WT is depicted as boxes located C-terminally of the GST tag used for purification purposes. The impaired SH2 or SH3 functionality of GSTGrb2 R86K or P49/206L, respectively, are indicated as crossed boxes in their respective SH domains.

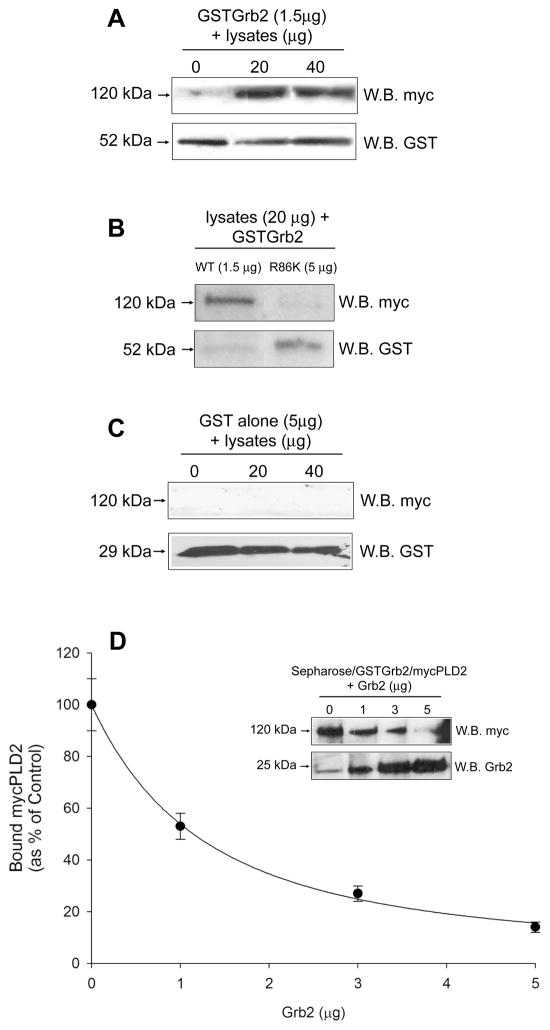

Binding of Grb2 to PLD2 is direct and specific

To address if PLD2 directly interacts with Grb2, a GST-fusion protein of human Grb2 and a SH2-deficient Grb2 mutant, R86K, were created and tested for the ability to bind mycPLD2 in in vitro GST-pull-down assays. As shown in Fig. 2A, purified GSTGrb2 interacts with mycPLD2. However, neither the SH2-deficient mutant (GSTGrb2 R86K) nor GST alone were able to pull down mycPLD2 (Fig. 2B and C, respectively), suggesting that the SH2 domain of Grb2 binds mycPLD2 in vitro. The specificity of the PLD2/Grb2 interaction was analyzed by incubation of Sepharose/GSTGrb2/mycPLD2 complexes with increasing amounts of purified Grb2. As indicated in Fig. 2D and inset, purified Grb2 caused an ~80% reduction in mycPLD2 bound to Sepharose beads. In conclusion, mycPLD2 specifically interacts with the SH2 domain of Grb2 in vitro.

Figure 2. PLD2 interacts with Grb2 in vitro.

The indicated amounts (in μg) of precleared COS-7 lysates expressing mycPLD2 were incubated with: (A) 1.5 mg purified Grb2, (B) 5 mg R86K or (C) 5 mg GST protein alone. After pull-down, the glutathione-Sepharose beads were subjected to SDS-PAGE and derived Western blots were probed with anti-myc and anti-GST antibodies. (D) In vitro binding competition of mycPLD2 to purified Grb2. The pulled-down complex Sepharose/GSTGrb2/mycPLD2 was incubated in the presence of increasing amounts of purified Grb2 protein (0, 1, 3 and 5 μg) and analyzed for the presence of mycPLD2.

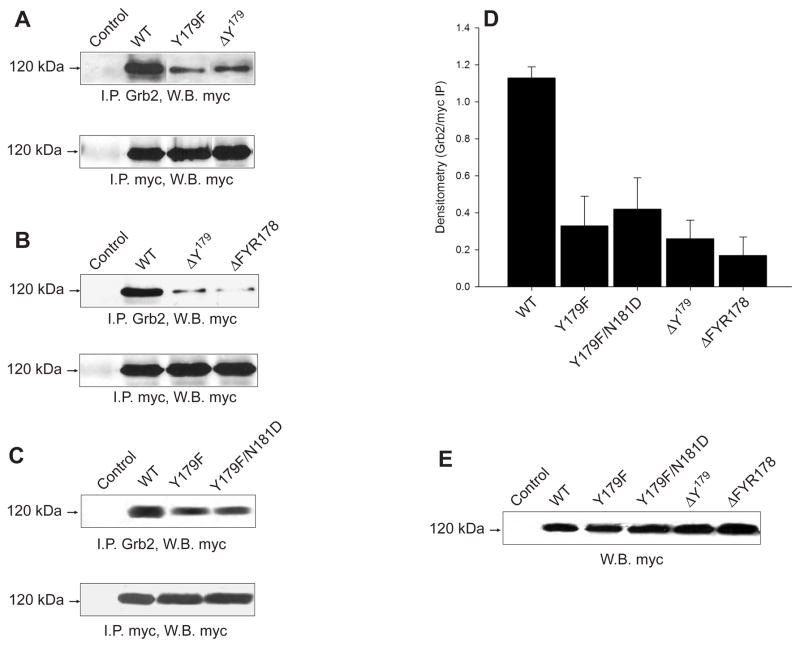

PLD2 Y179 is a docking site for Grb2

SH2-mediated interaction of Grb2 is exclusively mediated by a single phosphotyrosine residue at the N-terminal of the YxNx consensus (pYxNx) in the target protein (Songyang et al., 1993; Songyang et al., 1994). In silico analysis of the human PLD2 protein revealed Y179 as a potential site for the SH2-mediated Grb2 interaction: 179YRNY182. Thus, we analyzed the phosphorylation role of Y179 as well as its presence in Grb2 recruitment by replacing Y179 with the non-phosphorylatable residue F (Y179F) or by deleting it (DY179), respectively. Mutant plasmids were expressed in COS-7 cells, immunoprecipitated with an anti-Grb2 antibody, and the immunological presence of mycPLD2 was analyzed by Western blot. As shown in Figs. 3A and 3D, a ~70 % reduction in the co-immunoprecipitated mycPLD2 could be demonstrated with mycPLD2 Y179F and DY179, suggesting that PLD2 Y179 is involved in Grb2 binding in vivo. However, despite the fact that the phosphorylation of Y179, as well as by itself, are necessary for full binding of Grb2, it seems evident that other site(s) may also participate.

Figure 3. The PLD2 residue Y179 is involved in Grb2 interaction.

PLD2/Grb2 interaction in vivo. COS-7 lysates from cells transiently expressing mycPLD2 Y179F point mutant or deletion mutant DY179 (A), or DY179 and DFYR178 (B) or Y179F/N181D (C) were immunoprecipitated with anti-human Grb2 or anti-myc antibodies. Immunoprecipitates were separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-myc antibodies. (D) Densitometric analysis expressed as mean ± SEM (n=3) of the optical density of the immunoprecipitates normalized to myc signal (Grb2/myc IPs). (E) Shown is an anti-myc immunoblot of whole COS-7 lysates over expressing mycPLD2 WT and all Y179 mutants.

The selectivity of Grb2 binding is determined by an asparagine (N) at the +2 position of the consensus sequence pYxNx, whereas positions −2, −1, +1, and +3 are not likely to mediate Grb2 binding (Songyang et al., 1993; Songyang et al., 1994). Thus, the role of the 179YRNY182 consensus sequence in Grb2 binding was further analyzed by using the deletion mutants DY179 and DFYR178 (deletion of F178, Y179 and R180). As shown in Figs. 3B and 3D, the interaction with Grb2 decreases but is not totally eliminated. If N181 was mutated (Y179F/N181D), binding to Grb2 still occurred but it was also diminished by ~65 % (Figs. 3C and 3D). All this suggests that extra Grb2-interacting sites should exist in PLD2.

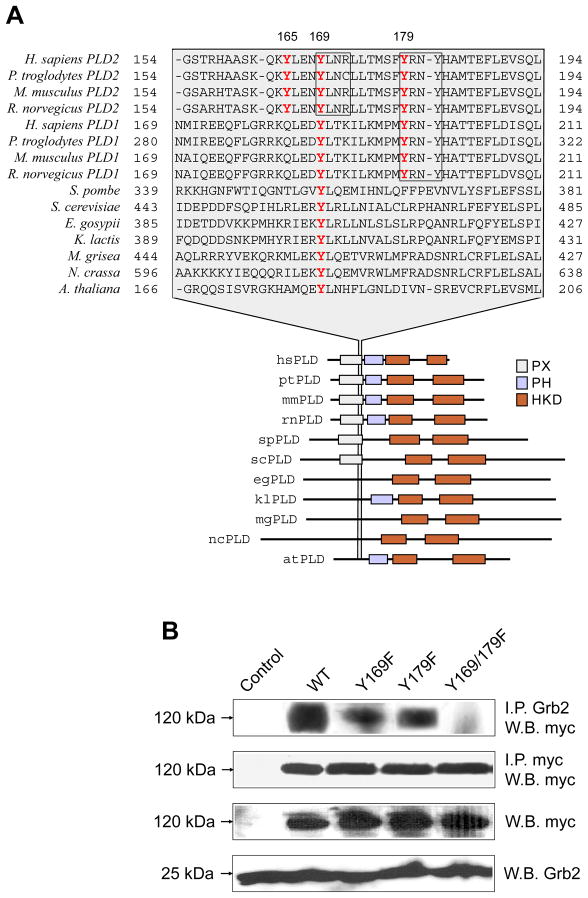

PLD2 Y169 is the second docking site for Grb2

Further analysis of the PLD2 sequence revealed a conserved Y169 as part of a perfect match for the consensus pYxNx (169YLNR172) (Fig. 4A). In order to investigate the role of Y169 in Grb2 binding, mycPLD2 mutants Y169F and Y169/179F were created. As shown in Fig. 4B, residue Y169 is involved in Grb2 binding. Moreover, the double mutant Y169/179F was unable to be co-imunoprecipitated with Grb2, demonstrating that full binding of endogenous Grb2 depends on Y169 and/or Y179 in PLD2. Y169 and Y179 are conserved in all eukaryotic PLDs and mammalian PLDs, respectively (Fig. 4A). The decrease in Grb2 binding to PLD2 observed in transfected COS-7 cells does not appear to be caused by decreased expression of mycPLD2 Y169 or Y179 mutants since comparable protein levels were demonstrated by direct myc Western blot of COS-7 lysates (Fig. 4B, bottom). Furthermore, mycPLD2 WT, Y169 or Y179 mutants showed no differences in their intracellular localization, as assayed by immunofluorescence (not shown).

Figure 4. Conserved PLD2 residues Y169 and Y179 are required for full Grb2 binding.

(A) Eukaryotic PLD homologies and conservation of Y165, Y169 and Y179. Protein sequence alignment of the C-terminal of PLD PX domains are shown in gray and the Y residues subject to this study are depicted in red. Boxed sequences represent the putative SH2-Grb2 consensus binding sites (B) PLD2/Grb2 interaction in vivo. COS-7 lysates from cells transiently expressing mycPLD2 WT, Y169F, Y179F or Y169/179F were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-Grb2 or anti-myc antibodies. Immunoprecipitates were separated by SDS-PAGE, immunoblotted, and the mycPLD2 levels were determined with anti-myc antibody probing. Also shown is an anti-myc immunoblot of whole COS-7 lysates over expressing mycPLD2 WT, Y169F, Y179F and Y169/179F mutants. Also shown are anti-myc and anti-Grb2 immunoblots of whole COS-7 lysates.

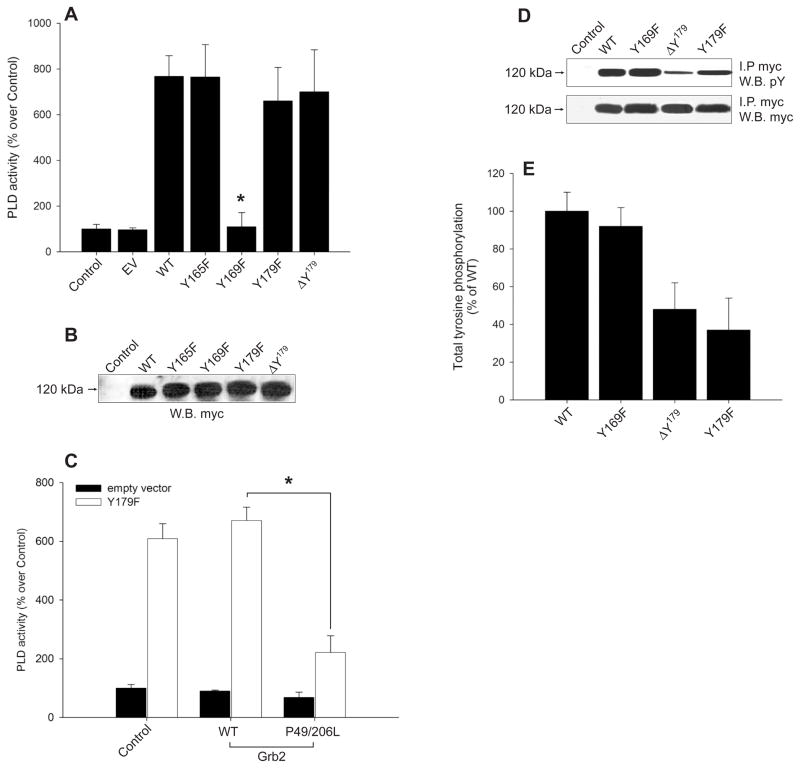

Functional uncoupling of PLD2’s Y169 and Y179

It has been demonstrated before that the removal of the first 183 amino acids of PLD2 render the protein inactive in vitro (Park et al., 2000; Sung et al., 1999). We investigated next the role of the Grb2-binding residues Y169 and Y179 (that are within those 183 N-end amino acids) in modulating PLD2 lipase activity. As shown in Fig. 5A and 5B, the F replacement of Y169 was enough to eliminate PLD activity, whereas Y179 is dispensable for PLD2 catalysis since mycPLD2 Y179F and DY179 are fully active enzymes. The same substitution of Y165 had no effect on PLD activity, as described earlier (Choi et al., 2004).

Figure 5. Functional uncoupling of Y169 and Y179.

(A) PLD activity of Control (non-transfected and transfected with empty vector (EV), WT or mutant plasmids. COS-7 lysates from cells transiently expressing mycPLD2 WT or mutants, were immunoprecipitated with anti-myc antibodies, and the immunoprecipitated proteins were analyzed for PLD activity in vitro. Results are expressed as % PLD activity (cpm/μg protein) over Control, as mean ± SEM (n=5, *p<0.001). (B) PLD2 WT and mutant expression levels determined by myc-immunoblot of whole COS-7 lysates (labeled as “W.B.” [not “I.P”]). (C) Role of residue Y169 in Grb2-mediated PLD2 activity. Myc immunoprecipitates of COS-7 transfected with empty vector (Control) or with fully active pcDNA-mycPLD2 Y179F or DY179, were incubated in the presence of purified GSTGrb2 WT (10 mg) or P49/206L (20 mg) and analyzed for PLD2 activity in vitro. Results are expressed as % PLD activity relative to Control treatment ± SEM (n=3, *p<0.001). (D) Tyrosine phosphorylation of PLD2 WT, Y169F, DY179 or Y179F probed with either anti-phosphotyrosine or with myc antibodies. (E) Shown is the densitometric analysis (optical density in arbitrary units normalized to myc signal) as mean ± SEM (n=3).

These results establish for the first time a vital role of Y169 in eliciting the high basal activity observed in PLD2. In order to confirm the role of PLD2 Y169 in high basal PLD2 activity, COS-7 lysates over expressing the fully active mutant mycPLD2 Y179F were immunoprecipitated and total PLD activity analyzed in vitro in the presence of competing amounts of GSTGrb2 P49/206L (a SH3-deficient mutant). As shown in Fig. 5C, mycPLD2 Y179F dropped its catalytic activity by ~70 % when GSTGrb2 P49/206L was included in the PLD assay (Fig. 5C). These results demonstrate that the SH2 domain of Grb2 interacts with Y169 and suggests that PLD2-Y169/Grb2 association is linked to high basal PLD2 activity via the SH3 domains of Grb2.

Once docked to their substrates via SH2, the SH3 domains of Grb2 recruit tyrosine kinases and phosphatases (Schlessinger, 1994), and tyrosine phosphorylation has been described for PLD2 activity (Houle & Bourgoin, 1999). Thus, we tested what might regulate the total phosphotyrosine content of PLD2. As shown in Figs. 5D and 5E, mycPLD2 WT and Y169F are tyrosine phosphorylated in a similar extent whereas transient transfection of mycPLD2 Y179F or DY179 resulted in hypo-phosphorylated proteins, as seen with a generic PY antibody. These results suggest that the complex PLD2-Y179/Grb2 is involved in the high phosphotyrosine content of PLD2.

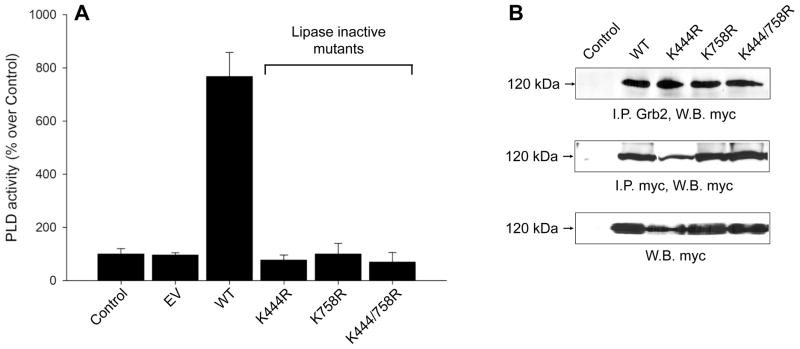

Binding of Grb2 to PLD2 is independent of enzyme activity

Since Y169 is required for basal PLD2 activity and Grb2 binding, we next examined if PLD2 catalysis and Grb2 binding are related phenomena. To this end, the catalytically inactive mutants, mycPLD2 K444R, K758R and K444/758R, were created and tested for PLD activity in vitro and for their ability to interact with endogenous Grb2 in vivo. As expected, mycPLD2 K444R, K758R and K444/758R mutants were inactive (Fig. 6A). However, no differences between inactive mutants and WT were observed in Grb2 binding (Fig. 6B), demonstrating that Grb2 recruitment to mycPLD2 is not impaired by deficient PLD activity. As a corollary, neither phosphatidic acid (PA) nor any of the PLD2-generated metabolites that might mediate tyrosine phosphorylation of PLD2, are involved in Grb2 binding in vivo.

Figure 6. PLD2 activity is not required for Grb2 binding.

(A) In vitro PLD activity of HKD mutants. COS-7 cells were transfected with empty vector (EV), mycPLD2 WT or lipase inactive mutants K444R, K758R and K444/758R. After 48 hs, cellular lysates were myc-immunoprecipitated and analyzed for PLD activity. (B) Interaction of PLD2 inactive mutants with Grb2 in vivo. COS-7 lysates from cells transiently expressing mycPLD2 K444R, K758R or K444/758R were immunoprecipitated with either anti-myc or anti-Grb2 antibodies. Immunoprecipitates were separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-myc. Transfected COS-7 whole cell lysates were also probed with anti-myc antibody (bottom panel).

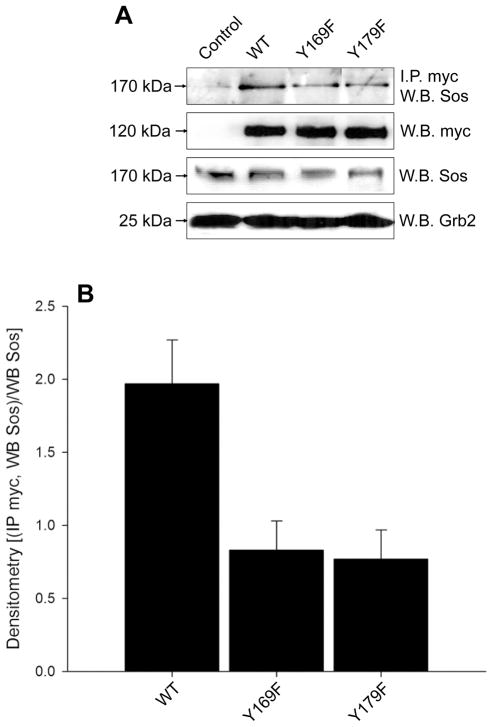

PLD2 residues Y169 and Y179 are involved in Sos recruitment

Grb2 exists as a complex with Sos in vivo (Chardin et al., 1993; Egan et al., 1993; Li et al., 1993). Since PLD2 associates with Grb2 via PLD2 Y169 and Y179, we tested the ability of PLD2 Y169F and Y179F to recruit Sos. As shown in Figs. 7A and 7B, mycPLD2 WT interacts with Sos in vivo. Furthermore, mutation of either Y169 or Y179 to phenylalanine led to a decreased Sos interaction with PLD2. These results suggest for the first time that PLD2 residues Y169 and Y179, which bind Grb2, are responsible for Sos recruitment, and that the complex PLD2/Grb2/Sos exists in vivo.

Figure 7. PLD2 residues Y169 and Y179 recruit Sos.

(A) PLD2 interaction with endogenous Sos. Cellular extracts of COS-7 cells transiently expressing WT or mutant plasmids were immunoprecipitated with an anti-myc antibody and the immunological presence of Sos (~170 kDa) analyzed by Western blot. As controls, basal expression of myc, Sos and Grb2 were analyzed simultaneously. (B) Densitometric analysis showing the reduction of in vivo Sos binding to mutant PLD2s. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM (n=3) of the optical density in arbitrary units of the myc-immunoprecipitates normalized to Sos signal [(IP myc, WB Sos)/WB Sos].

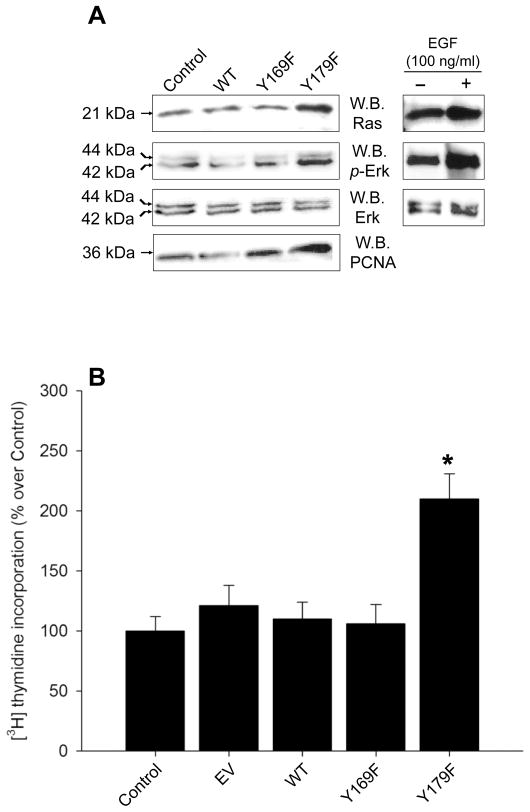

The PLD2 residue Y179 is negatively involved in Ras activation

The next question that needed to be addressed was what the physiological effect of the PLD2/Grb2/Sos complex might accomplish in the cell. It is well known that Grb2/Sos regulates Ras activation (Egan et al., 1993; Li et al., 2001). Transfection of COS-7 cells with mycPLD2 Y179F, but not with WT or Y169F, resulted in Ras activation (Fig. 8A). This indicates that the complex PLD2-Y169/Grb2/Sos is capable of stimulating Ras when the Y179 site is removed.

Figure 8. Analysis of the Ras/MAPK pathway and DNA synthesis.

(A) Ras activation induced by COS-7 transfection of WT and mutant plasmids. Cell lysates were incubated in the presence of Raf-1-RBD coupled to agarose beads and active Ras was purified and detected as indicated in Materials and Methods. Shown is a representative experiment done with 3 separate transfections [with pooled samples (n=6)]. Shown also are immunoblots of transfected COS-7 lysates probed with anti-Erk, -phospho-Erk, or -PCNA antibodies. For comparison purposes also shown here are positive controls 24 h-starved COS-7 cells stimulated with 100 ng/ml EGF and its effect on Ras and Erk. (B) De novo DNA synthesis as [3H]-thymidine incorporation. COS-7 cells Control [(non-transfected and transfected with empty vector (EV)] or transiently expressing WT or mutant plasmids, were incubated with 1 μCi/ml for 16 hours. TCA-precipitable [3H]-DNA was counted and referred as “% over Control” (mean ± SEM, n=9, *p<0.001).

As known, activation of Ras via the Grb2/Sos complex can engage cellular proliferation through mitogenic signaling cascades (Kyriakis & Avruch, 2001; Li et al., 1993). To test for a possible functional role of PLD2 on cellular proliferation, we studied Erk activation (as phosphorylation of p44/42Erk), commitment of cells to undergo S phase of the cell cycle [as upregulation of the proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA)] and de novo DNA synthesis (as [3H]-thymidine incorporation). Transient over expression of mycPLD2 Y179F resulted in the activation of p21 Ras, Erk, up regulation of PCNA expression (Fig. 8A) and increased [3H]-thymidine incorporation (Fig. 8B), whereas mycPLD2 Y169F did not. These results indicate that PLD2 residue Y179 is negatively involved in cell proliferation.

DISCUSSION

The data presented here identify for the first time two neighboring tyrosines, Y169 and Y179, in the PLD2 molecule as being essential for the Grb2/PLD2 interaction that our laboratory has described recently (Horn et al., 2005). The amino acids Y169 and Y179 in PLD2 are expressed within the context of perfect matches for SH2-mediated Grb2 interaction (pYxNx) (Songyang et al., 1993; Songyang et al., 1994). Pull-down assays using GSTGrb2 WT and a SH2-deficient mutant of Grb2 (R86K) demonstrate that the SH2 domain of Grb2 especificaly binds PLD2 in vitro. Molecular analysis of the interaction between endogenous Grb2 and PLD2 mutants revealed that PLD2 residues Y169 and Y179 are vital for Grb2 binding. We have also elucidated the function of the two tyrosines: Y169 serves to modulate the activity of the enzyme, while Y179 regulates total tyrosine phosphorylation of the protein.

The PLD2 residue Y169 is invariably present in the PX domain of all eukaryotic PLDs (and other proteins, i.e. p40phox and p47phox) (Xu et al., 2001), whereas residue Y179 is conserved only in the PX domain of mammalian PLDs. The N-terminal region of PLD2, containing the PX (a.a. 64–192) and PH (a.a. 210–313) domains, is the most representative region involved in PLD2 protein-protein interactions (Ahn et al., 2003; Jang et al., 2003; Kim et al., 2002; Park et al., 2000). The relevance of the PX domain is illustrated by the fact that its deletion from PLD2 produces a catalytically inactive enzyme in vitro (Park et al., 2000; Sung et al., 1999). However, the specificity of some PX-interactions to PLD2, but not other PX-containing proteins, raises the possibility that extra sequence determinants are dictating protein-protein interactions. Our discovery of the neighboring tyrosines Y169 and Y179 fills this gap.

The physiological relevance of PLD2-Y169 in PLD2 high basal activity is highlighted by the fact that mycPLD2 Y179F (and DY179, result not shown), otherwise a fully active enzyme, dropped its PLD activity by ~70 % in the presence of competing amounts of purified GSTGrb2 P49/206L, a SH3-deficient mutant of Grb2 (Fig. 5C). Consequently, we can draw the following three conclusions: i) the SH2 domain of Grb2 binds PLD2-Y169; ii) PLD2-Y169/Grb2 interaction is linked to high basal PLD2 activity, and iii) the SH3 domains of Grb2 are involved in the regulation of PLD2 activity.

Considering that substrate binding via the SH2 domain of Grb2 requires a phosphorylated tyrosine (pYxNx) (Songyang et al., 1993; Songyang et al., 1994), residues Y169 and Y179 appear to be phosphorylated in vivo by as-yet unknown mechanisms. In addition, Y169 and Y179 may be constitutively phosphorylated by mechanisms independent of PA and its metabolites since PLD2 activity is not necessary for Grb2 binding in vivo.

As for the correlation between PLD2 and tyrosine phosphorylation, it has been previously shown that PLD2 interacts with c-Src and other tyrosine kinases (Ahn et al., 2003; Choi et al., 2004; Slaaby et al., 1998), and the protein tyrosine phosphatase 1b (PTP1b) (Horn et al., 2005). Since the ternary complex PLD2/Grb2/PTP1b exists in vivo (Horn et al., 2005), it is possible that total tyrosine phosphorylation of PLD2 may also be regulated in a PLD2-Y179/Grb2-SH3-dependent manner. Supporting this are the findings that mycPLD2 Y179F and DY179 are hypo-phosphorylated proteins in vivo.

The SH3 domains of Grb2 interact with the C-terminal proline-rich domain of the Ras guaninenucleotide exchange factor, Sos (Chardin et al., 1993). As presented in Fig. 7, PLD2-Y169 and -Y179 are involved in Sos recruitment, likely via Grb2. Since mycPLD2 Y169F or Y179F showed impaired Sos interaction in vivo whereas simultaneous mutation of PLD2 Y169 and Y179, abolished it. Thus, the molecular complex PLD2/Grb2/Sos exists in vivo and depends on the presence of PLD2 residues Y169 and Y179.

It is well known that upon mitogenic stimulation, the Grb2/Sos complex increases Ras-mediated cell proliferation (Egan et al., 1993; Li et al., 1993). A role for PLD2 in cell proliferation is indirectly suggested by several reports showing that PLD activity is elevated in response to growth factors and oncogenes [Reviewed in (Foster & Xu, 2003)]. Data in Fig. 8 indicate that overexpression of mycPLD2 WT or Y169F do not stimulate cell proliferation, as assayed by Ras activation, Erk phosphorylation, PCNA expression or [3H]-thymidine incorporation. To explain this, either the PLD2-Y179/Grb2/Sos complex is keeping the proliferation machinery on hold, or PLD2 residue Y169 may be dispensable for cell proliferation. Over expression of mycPLD2 Y179F resulted in increased Ras activation, Erk (extracellular regulated kinase) phosphorylation, PCNA expression and de novo DNA synthesis. Since PLD2 Y179F is a fully active mutant which recruits Grb2/Sos via Y169, PLD2-Y169/Grb2/Sos might lead to cell proliferation stimulation.

The finding of Y179F increasing cell proliferation was unexpected. Since Grb2 only contains a single central SH2 domain while both Y169 and Y179 participate in PLD2/Grb2 complex formation, it is likely that Grb2 binds PLD2 in a 2:1 molar ratio. As such, the complex PLD2/Grb2/Sos appears to not be associated with cell proliferation. Upon PLD2 Y179 mutation/deletion, the PLD2 Y169/Grb2/Sos complex becomes involved in cell proliferation. Interestingly, the PLD2 sequence 169YLNRLLT175 overlaps with the predicted phosphorylation site for Akt kinase [(L/R)X(L/R)XX(pS/pT)] (Liu et al., 2002). As known, the PI3K/Akt cell survival pathway can be activated by Ras, as well as by PLD2 (Banno et al., 2005). Whether Akt phosphorylates PLD2 residue T175 modulating PLD2 Y169-mediated Ras/Erk and thus the balance between PLD2-mediated cell proliferation and cell death, remains to be demonstrated.

In conclusion, we have shown here that PLD2 is associated with Grb2 and Sos in vivo through PLD2 residues Y169 and Y179. Furthermore, Y169 and Y179 are functionally non-equivalent, despite their role in Grb2/Sos recruitment. While Y179 regulates total tyrosine phosphorylation of the protein, we propose that PLD2 residue Y169 is involved in PLD2’s catalysis and Ras/Erk-mediated cell proliferation via Grb2 recruitment and Grb2/Sos engagement, respectively. The elucidation of two neighboring tyrosines with distinct functionalities will undoubtedly help us understand the signal mechanisms followed by PLD2 in the cell.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids

The expression construct containing the full cDNA of human Grb2 variant 1 cDNA (pCMV6-Grb2, OriGene Technologies) was the template for PCR subcloning. The Grb2 ORF was PCR-amplified using the sense (EcoR I) primer 5′-CAC TGA GCA GAA TTC AGA ATG GAA GCC ATG GCC-3′ and the antisense (PspOM I) primer 5′-TTA AAT CCA ACG GGC CCT CCC ACC CCC TAA-3′. The PCR product was EcoR I/PspOM I-digested, purified and C-terminally subcloned into the EcoR I/Not I-digested Xpress-tagged pcDNA3.1/HisC expression vector (Invitrogen, Carlsbald, CA). The pcDNA-XGrb2 obtained was BamH I/Xho I-digested and the Grb2 insert was N-terminally subcloned in-frame into the glutathione S-transferase (GST)/IPTG-inducible prokaryotic expression vector pGEX-4T1 (Amersham). Molecular identities of pcDNA-XGrb2 and pGEX-GSTGrb2 were corroborated by direct nucleotide sequence (Cleveland Genomics, Cleveland OH).

Mutagenesis of pcDNA-mycPLD2 and pGEX-GSTGrb2

The construct pcDNA-mycPLD2 (Lopez et al, 1998) was used as a template to create deletion/point mutants following the QuickChange Site-Directed mutagenesis protocol (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). MycPLD2 Y179F, Y169F and Y179F/N181D were created by using the following sense primers: 5′-TC TTG ACC ATG TCT TTC TTT CGA AAC TAC CAT GCC-3′, 5′-CAG AAA TAC CTG GAG AAT TTT TTA AAC TGT CTC TTG ACC-3′ and TC TTG ACC ATG TCT TTC TTC CGG GAC TAC CAT GCC ATG ACA G, respectively. The double mutant Y169/179F was created by using pcDNA-mycPLD2 Y179F as a template and the Y169F mutagenic primer. The deletion mutants DY179 and DFYR178 were created by sequential deletions starting with the PLD2 Y179 codon (535TAT537). The sense mutagenic oligos used were as follows: DY179, 5′-CTC TTG ACC ATG TCT TTC CGG AAC TAC CAT GCC A-3′; and DFYR178, 5′-C TGT CTC TTG ACC ATG TCC AAC TAC CAT GCC ATG ACA G-3′. MycPLD2 inactive mutants were created by replacing lysines K444 and/or K758 from the first and second HKD domains, respectively, with arginine (K444R, K758R, K444/758R). The sense mutagenic primers used to create the SH2- (R86K) and SH3- (P49/206L) deficient versions of GSTGrb2 were: Grb2-R86K sense 5′-GAT GGG GCC TTT CTT ATA AAA GAG AGT GAG AGC GCT C-3′, Grb2 P49L sense 5′-TT AAT GGA AAA GAC GGC TTC ATT CTG AAG AAC TAC ATA GAA ATG AAA CCA C-3′ and Grb2 P206L sense 5′-G CAG ACC GGC ATG TTT CTG CGC AAT TAT GTC ACC C-3′ (all oligos and their reverse complements were PAGE/HPLC purified, Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA). Molecular identity of pcDNA-mycPLD2 and pGEX-GSTGrb2 mutants were corroborated by PCR, restriction digestion and direct sequence analysis (Cleveland Genomics, Cleveland OH).

GST fusion protein and in vitro GSTGrb2 binding assay

pGEX-GST (vector alone) and pGEX-GSTGrb2 were used to transform E. coli BL12 cells following standard procedures. GSTGrb2 fusion proteins and GST protein alone were harvested by sonication and purified with glutathione-Sepharose 4B beads following the manufacturer’s instructions. Protein purity was estimated on a 4–20 % SDS-PAGE. For in vitro binding studies, COS-7 cells transiently expressing pcDNA-mycPLD2, were lysed in lysis buffer (5 mM HEPES, 1 mM leupeptin, 768 nM aprotinin, 100 mM sodium orthovanadate and 0.5 % Triton X-100). After centrifugation, aliquots of the supernatant were cleared and incubated with purified GSTGrb2 (1.5 mg) or the SH2-deficient mutant R86K (5 mg) fusion proteins. The GSTGrb2/mycPLD2 complexes were pulled-down as follows: cleared lysates (20–40 μg) were incubated with GST-fusion proteins (or 5 μg GST alone) and glutathione-Sepharose 4B beads in a final volume of 400 μl of lysis buffer for 1 hour at 25 C. Protein complexes were collected by centrifugation and washed two times with lysis buffer. Bead-associated protein complexes were either resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred to a PVDF membrane, followed by immunoblot analysis with anti-myc or GST antibodies, or they were incubated again with an excess amount of purified Grb2 (1–5 mg) for 1 hr for the competition assay.

Transient transfection of COS-7 cells

COS-7 were initially seeded at 1×105 cells/well in 6-well tissue culture plates, in 2 ml D-MEM containing 10 % FBS and nonessential amino acids. Cells were grown at 37 C in a CO2 incubator until the cells were 70–80 % confluent (~30 h). Transfection was done as described previously utilizing lipofectamine as the DNA carrier (Horn et al., 2005).

Immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting

Immunoprecipitation with specific antibodies and immunoblotting were performed following procedures already published (Gomez-Cambronero et al., 2003; Lehman et al., 2003).

In vitro PLD assay

Phospholipase D activity (transphosphatidylation) in cell sonicates was measured in liposomes of shortchain PC, 1,2dioctanoylsnglycero3phosphocholine (PC8), and [3H]-butanol (Horn et al., 2001). Between 4060 mg of cell sonicates were added to 1.5ml microfuge Eppendorf tubes containing the following assay mix (120 ml final volume): 3.5 mM PC8 phospholipid, 1 mM PIP2, 75 mM HEPES, pH 7.9, and 2.3 mCi (4 mM) [3H]-butanol. When analyzing the role of Y169 in PLD activity, 10 mg GSTGrb2 WT or 10–20 mg GSTGrb2 P49/206L were added to the reaction media. The mixture was incubated for 20 minutes at 30 C and the reaction was stopped by adding 300 ml icecold chloroform/methanol (1:2) and 70 ml of 1 % perchloric acid. The tubes were then vortexed and 100 ml of 1 % perchloric acid and 100 ml of chloroform were added, vortexed again, centrifuged, and the upper phase was aspirated. The lower phase was washed once with 100 ml 1 % perchloric acid, an aliquot of 125 ml was removed, and dried for thinlayer chromatography (TLC). TLC lanes that migrated as authentic PBut were scraped, dissolved in 3 ml of Scintiverse II scintillation cocktail and counted. Background counts (from boiled samples) were subtracted from experimental samples.

Erk and Ras activity measurement

Erk activation was analyzed by immuno-detecting the phosphorylation state of p42/44Erk at residues T202/Y204 using specific antibodies (Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. MA) that detected a doublet of phosphoproteins on W.B. corresponding to pp42 and pp44 MAPKs. For Ras activation, GTP-bound Ras was affinity-purified from 500 mg of COS-7 lysates transiently expressing mycPLD2 WT or Y169/Y179 mutants by using the Ras-binding domain (RBD) of Raf1 coupled to agarose beads (RBD-Raf1-Agarose, Upstate, NY). Samples were incubated with 7.5 mg RBD-Raf1-Agarose 1 h at 4 C with gentle rocking and the beads pelleted, washed and resuspended in 25 ml 2X Laemmli buffer. Before PAGE (4–20 %), samples were boiled 5 minutes in the presence of 50 mM dithiothreitol. Membranes were blotted by using anti-Ras antibody (Cell Signaling, MA) and Western blots developed by the ECL method (Amersham, UK).

PCNA analysis and [3H]-Thymidine incorporation

Protein expression of the proliferation marker PCNA [proliferating cell nuclear antigen, (Prelich & Stillman, 1988)] was followed by immunoblot using a specific purified anti-PCNA antibody (PC10, BioLegend, CA). De novo DNA synthesis was measured as [3H]-thymidine incorporation into cellular DNA following standard procedures (Di Fulvio et al., 2000) with some modifications. After transient transfection, cells were washed twice with sterile PBS and incubated for 3 hours in serum-free DMEM. COS-7 cells were treated with 1 μCi/ml [3H]-thymidine/well for 16 h. Cells were washed twice with ice-cold PBS and precipitated with 5 % TCA at room temperature for 5 minutes. Precipitated cellular DNA was washed two times with 5 % TCA and solubilized by adding 550 μl/well of 12.5 N NaOH. Precipitable [3H]-DNA was measured by scintillation counting.

Statistical analysis

The analysis of multiple intergroup differences in each experiment was conducted by one-way analysis of variance followed by Student’s ttest. A p<0.05 was used as the criterion of statistical significance.

Acknowledgments

This work has been supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (HL056653) to JG-C.

References

- Ahn BH, Kim SY, Kim EH, Choi KS, Kwon TK, Lee YH, Chang JS, Kim MS, Jo YH, Min do S. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:3103–15. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.9.3103-3115.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banno Y, Ohguchi K, Matsumoto N, Koda M, Ueda M, Hara A, Dikic I, Nozawa Y. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:16319–24. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410903200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourgoin S, Grinstein S. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:11908–11916. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chardin P, Camonis JH, Gale NW, van Aelst L, Schlessinger J, Wigler MH, Bar-Sagi D. Science. 1993;260:1338–43. doi: 10.1126/science.8493579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi WS, Hiragun T, Lee JH, Kim YM, Kim HP, Chahdi A, Her E, Han JW, Beaven MA. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:6980–92. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.16.6980-6992.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cockcroft S. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2001;58:1674–87. doi: 10.1007/PL00000805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Fulvio M, Coleoni AH, Pellizas CG, Masini-Repiso AM. J Endocrinol. 2000;166:173–82. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1660173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan SE, Giddings BW, Brooks MW, Buday L, Sizeland AM, Weinberg RA. Nature. 1993;363:45–51. doi: 10.1038/363045a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Exton JH. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1436:105–115. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2760(98)00124-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster DA, Xu L. Mol Cancer Res. 2003;1:789–800. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Cambronero J, Horn J, Paul CC, Baumann MA. J Immunol. 2003;171:6846–55. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.12.6846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond SM, Jenco JM, Nakashima S, Cadwallader K, Gu Q, Cook S, Nozawa Y, Prestwich GD, Frohman MA, Morris AJ. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:3860–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.6.3860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn J, Lopez I, Miller MW, Gomez-Cambronero J. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;332:58–67. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.04.093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn JM, Lehman JA, Alter G, Horwitz J, Gomez-Cambronero J. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2001;1530:97–110. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(00)00172-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houle MG, Bourgoin S. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1439:135–49. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(99)00090-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang IH, Lee S, Park JB, Kim JH, Lee CS, Hur EM, Kim IS, Kim KT, Yagisawa H, Suh PG, Ryu SH. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:18184–90. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208438200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JH, Lee S, Lee TG, Hirata M, Suh PG, Ryu SH. Biochemistry. 2002;41:3414–21. doi: 10.1021/bi015700a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyriakis JM, Avruch J. Physiol Rev. 2001;81:807–69. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.2.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehman JA, Calvo V, Gomez-Cambronero J. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:28130–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300376200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li N, Batzer A, Daly R, Yajnik V, Skolnik E, Chardin P, Bar-Sagi D, Margolis B, Schlessinger J. Nature. 1993;363:85–8. doi: 10.1038/363085a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Couvillon AD, Brasher BB, Van Etten RA. Embo J. 2001;20:6793–804. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.23.6793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu MY, Cai S, Espejo A, Bedford MT, Walker CL. Cancer Res. 2002;62:6475–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez I, Arnold RS, Lambeth JD. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:12846–12852. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.21.12846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowenstein EJ, Daly RJ, Batzer AG, Li W, Margolis B, Lammers R, Ullrich A, Skolnik EY, Bar-Sagi D, Schlessinger J. Cell. 1992;70:431–42. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90167-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park JB, Kim JH, Kim Y, Ha SH, Yoo JS, Du G, Frohman MA, Suh PG, Ryu SH. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:21295–301. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002463200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park SK, Provost JJ, Bae CD, Ho WT, Exton JH. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:29263–29271. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.46.29263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powner DJ, Wakelam MJ. FEBS Lett. 2002;531:62–4. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03410-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prelich G, Stillman B. Cell. 1988;53:117–26. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90493-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlessinger J. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1994;4:25–30. doi: 10.1016/0959-437x(94)90087-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slaaby R, Jensen T, Hansen HS, Frohman MA, Seedorf K. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:33722–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.50.33722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Songyang Z, Shoelson SE, Chaudhuri M, Gish G, Pawson T, Haser WG, King F, Roberts T, Ratnofsky S, Lechleider RJ, et al. Cell. 1993;72:767–78. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90404-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Songyang Z, Shoelson SE, McGlade J, Olivier P, Pawson T, Bustelo XR, Barbacid M, Sabe H, Hanafusa H, Yi T, et al. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:2777–85. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.4.2777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sung TC, Altshuller YM, Morris AJ, Frohman MA. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:494–502. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.1.494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sung TC, Roper RL, Zhang Y, Rudge SA, Temel R, Hammond SM, Morris AJ, Moss B, Engebrecht J, Frohman MA. Embo J. 1997;16:4519–30. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.15.4519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y, Seet LF, Hanson B, Hong W. Biochem J. 2001;360:513–30. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3600513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]