Abstract

Objectives

Most work on ischemia-induced neuronal death has revolved around the relative contributions of necrosis and apoptosis, but this work has not accounted for the role of ischemia-induced stress responses. An expanded view recognizes a competition between ischemia-induced damage mechanisms and stress responses in the genesis of ischemia-induced neuronal death. An important marker of post-ischemic stress responses is inhibition of neuronal protein synthesis, a morphological correlate of which is the compartmentalization of mRNA away from ribosomes in the form of cytoplasmic mRNA granules.

Methods

Here we assessed the generality of this mRNA granule response following either 10 or 15 minutes global brain ischemia and 1 hour reperfusion, 4 hours focal cerebral ischemia alone, and endothelin 1 intraventricular injection.

Results

Both global and focal ischemia led to prominent neuronal cytoplasmic mRNA granule formation in layer II cortical neurons. In addition, we report here new post-ischemic cellular phenotypes characterized by the loss of nuclear polyadenylated mRNA staining in cortical neurons following endothelin 1 treatment and 15 minutes global ischemia. Both mRNA granulation and loss of nuclear mRNAs occurred in non-shrunken post-ischemic neurons.

Discussion

Where cytoplasmic mRNA granules generally appear to mark a protective response in surviving cells, loss of nuclear mRNAs may mark cellular damage leading to cell atrophy/death. Hence, staining for total mRNA may reveal facets of the competition between stress responses and damage mechanisms at early stages in post-ischemic neurons.

Keywords: brain ischemia and reperfusion, endothelin 1, mRNA granules, protein synthesis inhibition

INTRODUCTION

Discovering the causes of neuronal demise following ischemia has proven to be a formidable task. In part this is due to the heterogeneity of cell death forms as a function of the type of ischemic insult (global, focal, complete, and incomplete) and in part to the non-mutual exclusivity of pathways1,2 and phenotypes3 leading to necrotic or apoptotic cell death. One conceptual barrier that has stood in the way of developing a comprehensive theory of ischemia-induced neuronal death is the idea that such death is directly caused by ischemia-induced cellular damage. While this is clearly true of prolonged intense ischemic insults4, such a view may provide incomplete understanding of delayed forms of neuronal death found after global ischemia and reperfusion or in penumbral neurons following focal ischemia.

A key concern with any view in which cell death is thought to be directly caused by damage pathways (be these necrotic or apoptotic) is that such a view assigns an essentially passive role to the affected cells. An expanded point of view, that is gaining increasing appreciation, also includes consideration of the neuron's ability to combat damage following ischemia and reperfusion5,6,7. In such a view, the affected cells are not passive with respect to the accumulation of damage but actively “fight back” against the damage. It is well established that post-ischemic neurons, under the appropriate conditions, induce, or try to induce, important intracellular stress response such as the heat shock response8,9, endoplasmic reticulum stress response pathways10,11 and DNA repair pathways12,13. It is possible to formally model the cellular response to ischemia as a bistable competition between induced stress responses and damage mechanisms14,15. If total damage exceeds the cell's total ability to cope, the cell will die. If the cell's stress responses win out over damage mechanisms, the cells survive. This type of model has several advantages as it accounts for: (1) the empirical data under conditions where both damage pathways and stress responses are induced in post-ischemic neurons, (2) the delay in cell death as the time required for the competition between damage pathways and stress responses to play out, (3) not only for why some cells die, but also explains how other neurons can survive the ischemia, e.g. that stress responses successfully combat ischemia-induced damage and facilitate neuronal repair and restoration in ischemia-resistant neurons.

We recently showed that staining for polyadenylated mRNAs using fluorescent in situ hybridization following 10 minutes global brain ischemia served to mark changes in hippocampal neurons related to stress response induction16. In post-ischemic neurons polyadenylated mRNAs formed a granular pattern that we termed “mRNA granules”. The mRNA granules correlated with: (1) post-ischemic inhibition of protein synthesis, and (2) expression of the heat shock response16. The occurrence of mRNA granules was reversed after 16 hours reperfusion in ischemia-resistant CA3 neurons but persisted in ischemia-vulnerable CA1 neurons that never recovered normal protein synthesis and died by 72 hours reperfusion. Thus we have interpreted the mRNA granules to represent a morphological marker of a genetic reprogramming of post-ischemic neurons into a stress response phenotype17.

To determine the generality of the mRNA granule responses we here used polyadenylated mRNA staining to characterize a wider variety of ischemic conditions including global brain ischemia and reperfusion, focal cerebral ischemia, and endothelin 1 intraventricular injection. Endothelin 1 is a small peptide with strong vasoconstrictor properties18,19 which plays a role in the regulation of cerebral circulation20, and has been used as a means to induce focal brain ischemia by a variety of routes of administration21,22,23. Both global and focal ischemia led to prominent neuronal cytoplasmic mRNA granule formation in layer II cortical neurons. In addition, we report here new post-ischemic phenotypes characterized by the loss of nuclear polyadenylated mRNA staining in cortical neurons following endothelin 1 treatment and 15 minutes global ischemia. Both mRNA granulation and loss of nuclear mRNAs occurred in non-shrunken post-ischemic neurons. Where mRNA granules generally appear to mark a protective response in surviving cells, loss of nuclear mRNAs may mark cellular damage leading to atrophy/death. Hence, staining for total mRNA may reveal facets of the competition between stress responses and damage mechanisms at early stages in post-ischemic neurons.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Alexa 488-labeled streptavidin (S32354) was obtained from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, California). Biotinylated goat anti-streptavidin (BA-0500) was purchased from Vector Laboratories (Burlingame, CA). A 5'-biotinylated 50-mer oligo-dT probe was made by Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc. (Coralville, IA). Prehybridization and hybridization buffers were obtained from the mRNA locator In Situ Hybridization Kit (Ambion, Austin, TX). Fluoro-Jade was purchased from Histochem Inc., (Jefferson, AR). All other chemicals were reagent grade.

Animal Models

All animal experiments were approved by the Wayne State University Institutional Animal and Care Use Committee and were conducted following the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Research Council, revised 1996). All efforts were made to reduce animal suffering and minimize the total number of animals used.

Endothelin 1 Treatment

Male Long Evans rats were anesthetized with ketamine and xylazine (100mk/kg, 10mg/kg, respectively), heads shaved and then symmetrically fixed by ear bars, front teeth, and nosebar into a stereotaxic frame. A one-inch incision was made down the midline of the scalp and the exposed skull cleared of tissue. Coordinates for injection into the lateral ventricle were: posterior −0.80 mm, lateral −1.5 mm, ventral −3.8 mm, all relative to Bregma24. Bilateral holes were drilled and a 21-guage needle lowered sequentially into the lateral ventricles. Endothelin 1 or vehicle was injected in 10 microliters over 10 seconds, and the needle left in place for an additional 1 minute. Endothelin 1 treatment was randomly assigned to animals in five experimental groups: (1) vehicle (normal saline) only, (2) 100 pg, (3) 200 pg, (4) 400 pg, and (5) 800 pg endothelin 1. These injection amounts corresponded to 25 mM, 50 mM, 100 mM and 200 mM endothelin 1, respectively. Following endothelin 1 injection, rats were released from the stereotaxic frame and the wound sealed by staples. Animals were returned to their cages for 4 hours at which time they were used either for measuring cerebral blood flow (n= 3 per experimental group) or perfusion fixed for tissue staining (n=3–5 per experimental group).

Global Brain Ischemia and Reperfusion

Global forebrain ischemia was induced in male Long Evans rats using the bilateral carotid artery (two-vessel) occlusion and hypovolemic hypotension model of Smith et al. (1984)25, as we have previously described16,26,27. Rats were maintained normothermic during the entire ischemic period and for the first hour of reperfusion. Post-surgical animals displaying necrosis, weight loss > 15% initial body weight/day, or sustained seizure activity were excluded from the study. Our overall survival rate for the reperfusion groups was 75%. Experimental groups were: sham-operated, nonischemic controls, 10 minutes ischemia and 60 minutes reperfusion and 15 minutes ischemia and 1 hour reperfusion. There were 3 animals per each experimental group. At the appropriate time, animals were perfusion fixed as previously described16.

Focal Brain Ischemia

Unilateral focal brain ischemia was induced in male Long Evans rats using the middle cerebral artery occlusion intraluminal suture model of Hatashita et al. (1990)28, as previously described29,30,31. This model has been well validated with respect to localized infarct and penumbral development29,30,31. Rats were maintained normothermic during the entire ischemic period and, where appropriate, for the first hour of reperfusion. Animals undergoing reperfusion were anesthetized in 5% halothane at the end of the ischemic period, followed by removal of the nylon filament. At the end of experimental periods, animals were perfusion fixed as described above. Experimental groups were: sham-operated, nonischemic controls, 4 hour ischemia only, and 2 hours ischemia and 24 hours reperfusion. There were 3 animals per each experimental group.

Measurement of cerebral blood flow by Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Prior to image acquisition, anesthesia was induced by a steady application of 1% halothane using a specially designed apparatus compatible with the Magnetic resonance imaging to sedate the animals. The animal was placed in a prone position on a cradle with a custom-built palate holder equipped with an adjustable nose cone and stereotaxic ear bars in order to minimize movement during magnetic resonance imaging scans.

The rat head was positioned at the isocenter of a magnet. Magnetic resonance imaging scans were repeated at four time points. Baseline scans were run before traumatic brain injury was induced, and then at the 4th hour, 24th hour and 48th hour post-traumatic brain injury. All magnetic resonance imaging measurements were performed on a 4.7-T horizontal-bore magnetic resonance spectrometer (Bruker AVANCE) with an 11.6-cm-bore actively shielded gradient coil set capable of producing a magnetic field gradient of up to 250 mT/m. A whole-body birdcage radiofrequency coil (inner diameter, 72 mm) was used as the transmitter for homogeneous radio frequency excitation, and a surface coil (30 mm diameter) was used as the receiver, with active radio frequency decoupling to avoid signal interference. Three sequences were run in this set of experiments: T2-weighted imaging, T1-weighted imaging, and ASL for the measurement of flow.

For all sequences, the field of view was 40×40×24 mm3; thus, the whole brain was imaged. The remaining imaging parameters used are as follows:T2-weighted imaging Rapid Acquisition with Relaxation Enhancement: TR=4751 ms, TE=46 ms, matrix size Nx×Ny =256×256, number of slices (Ns)=24 (thickness, 1 mm), Nacq=1; T1-weighted imaging (three-dimension Fast Low Angle Shot [FLASH]): TR=22 ms, TE=7 ms, flip angle (FA)=58 and 208, matrix size Nx×Ny×Nz =256×256×24, Nacq=1(FAs 58 and 208 will be used to calculate T1 maps); ASL: TR = 1550 ms, TE = 7.65 ms, matrix size Nx×Ny =128×70 (interpolated by zero filling in k-space to 256_256), slice=1 (thickness, 2 mm), Nacq=2, labeling slice=2 cm offset from isocenter, adiabatic fast passage with Magnetization transfer contrast gradients=1.5 s, spin echo=3.

Tissue Staining

Polyadenylated mRNAs were detected by fluorescence in situ hybridization using a 50-mer poly-T probe as previously described16. The Fluoro-Jade procedure was exactly that of Schmued et al. (1997)32. Fluoro-Jade slides were examined using excitation at 488 nm and emission at 518 nm. For middle cerebral artery occlusion samples, 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride staining was used to measure tissue viability and evaluate infarct size as previously described31.

Data Analysis

For blood flow measurements, multiple experimental groups were compared by analysis of variance followed by Tukey post-hoc analysis. For measurements of cortical neuron loss after endothelin 1 treatment, visualized by polyadenylated mRNA fluorescence in situ hybridization staining, estimates of percentage cell loss and percent area in which cell loss occurred were performed by evaluating the entire cerebral cortex in the tissue slice at 10×. Cell loss was confirmed by viewing at 40× to distinguish cell loss from weak staining. The percent of damaged area and of cell loss were both compared by analysis of variance followed by Tukey post hoc if necessary.

The majority of results reported here are descriptive and based on endothelin 1 reconstruction of tissue using an ApoTome-equipped microscope as previously described16,33. Stacks of optically-sectioned tissue slices were acquired under a 63× oil immersion lens where each pixel represented spatial dimensions of x = 0.1 micron, y = 0.1 micron, and z = 0.35 micron. Acquired z-stacks were used for the construction of maximum intensity orthographic projections stacks in NIH Image J34. Photomontages were manually constructed in Photoshop CS (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA). Volumetric and isosurface three-dimensional reconstructions were performed in Amera 5.2 (Visage Imagining, Andover, MA).

RESULTS

Endothelin 1 and cerebral blood flow

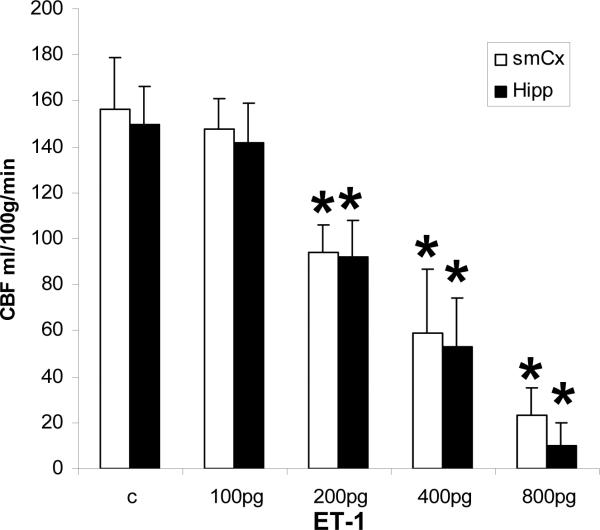

Figure 1 shows the result of local cerebral blood flow measurements in cerebral cortex and hippocampus in vehicle-treated and from 100–800 pg endothelin 1 administration. The 100 pg dose had no effect on blood flow in either region. A dose dependent decrease in blood flow was observed from 200 pg to 800 pg endothelin 1. Blood flow was reduced by one third and one half with 200 and 400 pg endothelin 1, respectively, and no difference in decrease occurred between cerebral cortex or hippocampus. At 800 pg endothelin 1, cortical blood flow was decreased 80%, and hippocampal blood flow was decreased 94%.

Figure 1.

Local cerebral blood flow (CBF) determined by magnetic resonance imaging at 4 hours following endothelin 1(ET-1) intraventricular injection. smCX, sensorimotor cortex; Hipp, hippocampus.

The graded decrease in blood flow led us to hypothesize that we would observe graded effects in brain tissue injury following endothelin 1 administration. However, results from our in situ studies described below indicated that the graded changes in blood flow were only apparent, and likely represented averages of inhomogeneous patterns of blood flow reduction.

Endothelin 1-induced cortical damage

Figure 2 shows coronal sections of the endothelin 1 injection site at −0.8 mm posterior to Bregma, and the level of brain section chosen for evaluation at −3.0 mm posterior to Bregma containing the dorsal hippocampus. Ventral and lateral injection coordinates are indicated by red arrows on the left image. Slices were evaluated 2.2 mm posterior to the site of endothelin 1 injection to avoid damage due to the injection site. We excluded slices showing cortical damage that had obviously resulted from the injection tract into the brain. As described below, damage occurred heterogeneously throughout the entire area of the cerebral cortex, marked by red lines in the right image of Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Coronal sections showing coordinates of endothelin 1 (ET-1) intraventricular injection and the slice chosen for microscopic analysis using polyadenylated mRNA fluorescence in situ hybridization. Red arrows mark lateral and ventral injection coordinates. Red stripped area on right image shows the extent of cerebral cortex evaluated and served as 100% for area measurements in Table 1. Inset: midsagittal section showing locations of the two coronal sections. Images adapted from reference [24]. pB, posterior to Bregma.

Table 1 lists averages for the total area of cerebral cortex displaying evidence of cell damage or death following endothelin 1 injection, as evaluated by polyadenylated mRNA fluorescence in situ hybridization staining. Table 1 also lists the decrease in the number of cells, expressed as a percentage of controls, in areas displaying cellular damage. The criteria for designating an area as “damaged” included: (1) decreased density of cells, (2) altered cell morphology from controls, usually, but not exclusively, in the form of cell shrinkage and distortion, and (3) a significant decrease in cell staining compared to undamaged areas. The values in Table 1 are only rough indicators of cell damage because of the heterogeneity we report below.

TABLE 1.

Average percent cell death and damaged cortical area following endothelin 1 treatment. ANOVA p = 0.007 (% area damaged); ANOVA p = 0.068 (% decrease in cell number).

| n | # animals with cortical damage | % area damaged (mean ± st. dev.) | % decrease in cell number (mean ± st. dev.) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 200 pg endothelin 1 | 3 | 1 | 10.0 ± 17.3* | 20.0 ± 34.6 |

| 400 pg endothelin 1 | 5 | 5 | 48.1 ± 17.8 | 54.0 ± 5.5 |

| 800 pg endothelin 1 | 3 | 3 | 67.5 ± 10.9 | 58.2 ± 14.4 |

post hoc p < 0.05 compared to respective experimental groups.

There was a trend toward a dose-dependent increase in the area of cerebral cortex showing cell damage from 200–800 pg endothelin 1. However, for 200 pg only one of three animals showed evidence of damage at −3.0 mm posterior to Bregma. It is possible that other slices in the 200 pg samples showed damage, but we did not observe them due to our adherence to fixed coordinates for analysis. All of the 400 pg and 800 pg treated animals showed evidence of cerebral cortical damage at −3.0 mm posterior to Bregma. The respective percent area damaged did not clear statistically because the 400 pg samples showed wide variation, ranging from 18% to 63% of cortical area damaged. The 800 pg samples showed less variation, ranging from 60%–80% damaged area. For all three experimental groups, the percentage decrease in cells within the damaged areas averaged about 50% and there was no statistical difference amongst the groups.

Assessment of cortical histology after endothelin 1 treatment

Histological assessment of cortical damage by polyadenylated mRNA staining showed the heterogeneity in damage distribution. Figure 3 shows polyadenylated mRNA staining for each endothelin 1 doses under both low (10×) and high (40×) power objectives. The 100 pg group was excluded from polyadenylated mRNA staining because this group showed no decrease in cerebral blood flow (Figure 1). Figure 3 includes the single 200 pg endothelin 1 treated animal that displayed cortical damage at the slice level we evaluated (see also Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Effect of endothelin 1 on histology of cerebral cortex as assessed by polyadenylated mRNA fluorescence in situ hybridization. Left column: low power (10× objective) photomicrographs. Right column: high power (40×) photomicrographs. endothelin 1 doses as specified to the left. 40× images are from areas marked by white dashed boxes indicated on respective 10× images. Arrows in D and F point to shrunken neurons identified in the text as ischemic cell change. Arrows in G point to microclots in capillaries. Arrows in H point to neurons lacking polyadenylated mRNA nuclear staining. Scale bar in G applies to all images at 10× and scale bar in H applies to all images at 40×.

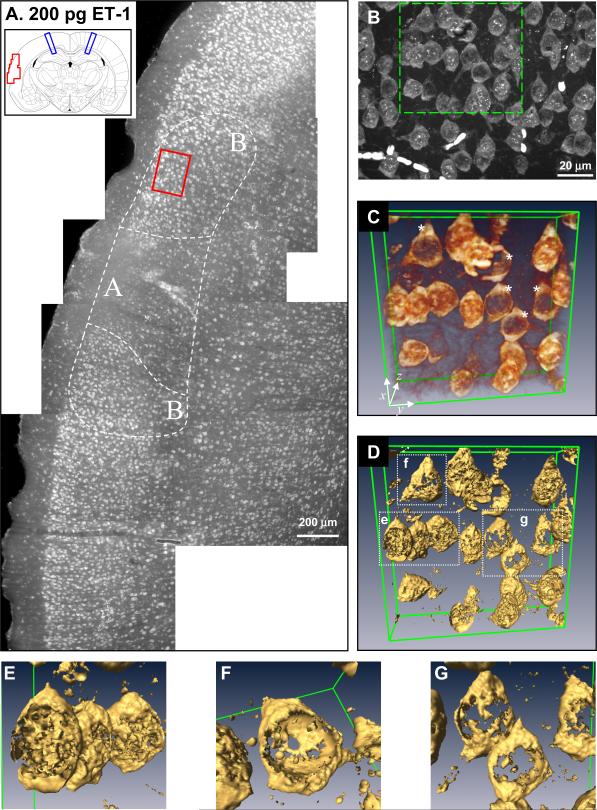

Figure 4.

Detailed analysis and three-dimensional reconstructions of cerebral cortical histology of layer II neurons assessed by polyadenylated mRNA fluorescence in situ hybridization following 200 pg endothelin 1(ET-1) intraventricular injection. (A) Photomontage of the area of cerebral cortex marked by the red box on the coronal section in the inset. Each individual micrograph was taken under 10× objective. Blue lines on inset mark the area of injection 2.8 mm anterior to the coronal section. Area A marks area of maximal damage and areas B mark adjacent areas of lesser damage as described in the text. (B) Orthographic projection of area B taken under 63× oil immersion lens of the area marked by the red box in A. (C) Endothelin 1 volumetric rendering of the volume marked by the green box in B. Green lines indicate extent of rendered volume and coordinate axis provides orientation. Asterisks (*) denote cells showing loss of polyadenylated mRNA nuclear staining. (D) Isosurface rendering of volume shown in C. (E) Close-up of isosurface rendering of boxed volume labeled “e” in D showing nuclear speckles. (F) Close-up of isosurface rendering of boxed volume labeled “f” in D showing empty nuclear volume. (G) Close-up of isosurface rendering of boxed volume labeled “g” in D showing neurons lacking polyadenylated mRNA nuclear staining.

Non-ischemic control layer II cortical neurons (Figure 3B) had the same three general features of polyadenylated mRNA staining we reported previously for hippocampal neurons16: (1) diffuse and relatively homogeneous polyadenylated mRNA staining throughout the entire cytoplasm, (2) occasional small and circular intense polyadenylated mRNA cytoplasmic staining that we previously showed were stress granules16 (e.g. Figure 5A, white arrows), and (3) the presence, inside the area of the nucleus, of several intense, roughly circular structures ranging from 0.5 – 2 μm (“nuclear speckles”, see below) against a weak background of diffuse polyadenylated mRNA staining.

Figure 5.

Polyadenylated mRNA fluorescence in situ hybridization of cortical layer II following focal cerebral ischemia. (A) Photomicrograph (63× oil immersion) of an orthographic projection from cortical layer II of sham-operated control. Arrows point to stress granules. (B) Three-dimensional volumetric rendering of a sham-operated or non-ischemic control (NIC) in layer II (LII) neuron. Cytoplasm false colored in green hues and nucleus in orange hues. Orange box shows total volume. (C) Photomicrograph (63× oil immersion) of an orthographic projection from ipsilateral cortical layer II after 4 hours (4hI) of middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) induced focal cerebral ischemia. Arrows point to putative ischemic cell change cells. Inset: shrunken and pyknotic neurons in layer VI (LIV) of the same coronal section. Inset scale bar is 5 microns. (D) Three-dimensional volumetric rendering of a 4 hour middle cerebral artery occlusion layer II neuron colored as in B. Orange box shows total volume. (E) Coronal section from which photomicrographs in A and C were derived. Green area marks area of neurons containing mRNA granules; box marks location of panel C. Red area marks shrunken and pyknotic neurons; box marks location of inset of panel C. (F) 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride staining of 1 mm slices through anterior of brain containing striatum of sham-operated non-ischemic control and 4 hour middle cerebral artery occlusion samples.

As can be seen from the progression of images in Figure 2, layers II and III of the cerebral cortex were most strongly affected. The 200 pg sample shows decreased cell density and cell shrinkage (Figure 2C and D) as compared to controls (Figure 2A and B). The 400 pg samples showed greater numbers of shrunken cells and areas devoid of cell staining. In the 800 pg samples, the damage extended into other cerebral cortical layers, and the areas devoid of cell staining were generally larger than the 400 pg group. Occasionally, microclots were observed in which red blood cells trapped in capillaries were stained by the poly-T probe (Figure 3G, arrows).

With respect to polyadenylated mRNA staining at high magnification, we did not observe mRNA granules in any of the neurons following any dose of endothelin 1. Instead we observed one of two general patterns. In the first, polyadenylated mRNA staining of shrunken and distorted cells was reminiscent of that of controls with an apparently homogenous cytoplasm and intense nuclear polyadenylated mRNA staining (Figure endothelin 1 and 3F, arrows). However, in the second polyadenylated mRNA staining pattern, we observed in many cases that cells were devoid of nuclear polyadenylated mRNA staining and that such cells, though distorted to some extent, were generally not shrunken (Figure 3H, arrows).

Loss of polyadenylated mRNA nuclear staining after endothelin 1 treatment

A more detailed study of polyadenylated mRNA staining associated with cell loss is provided in Figure 4. The single 200 pg sample that displayed damage proved fortuitous for this purpose due to the lesser complexity of its damage distribution compared to any of the 400 or 800 pg endothelin 1 samples. Figure 4A shows a photomontage of a portion of left hemisphere cortex marked by the red box in the inset. This montage shows two clearly distinguishable areas of damage (A and B in Figure 4A). The discreet regions of cortical damage shown in the montage of Figure 4A suggests the damaged areas experienced a substantial decrease in blood flow compared to surrounding regions.

Area A appeared to be the epicenter of damage and was distinguished by a wholesale loss of neuronal staining throughout layers II and III. Neurons detectable in area A were shrunken and distorted (Figure 3F). Area B occurred on either side of area A. In area B, while the cell density was lower than the surrounding undamaged areas, high power magnification revealed that neurons in area B consisted of two readily identifiable populations: 1) neurons containing the polyadenylated mRNA nuclear staining as seen in controls, and 2) neurons that lacked the nuclear polyadenylated mRNA staining (Figure 4B).

We16 and others35 have observed prominent “nuclear speckles” of polyadenylated mRNA staining in the nucleus of neurons. There are typically 3–6 of these nuclear speckles visible in the nucleus as intensely stained, roughly ovoid (elliptical or circular in cross section) structures 1/2 to 1 micron in diameter. In all likelihood, these represent areas of concentrated mRNA transcription and processing, in which the polyadenylated-tail has been added to nascent mRNA transcripts before their exit from the nucleus. When orthographic projections (Figure 4B) and three-dimensional volumetric reconstructions (Figures 4C–G) of area B were generated from 63× oil immersion image stacks (n=60 slices, z depth = 21 microns), some neurons indeed showed lack of nuclear speckles and a clear decrease of nuclear polyadenylated staining (Figure 4C, asterisks).

To get a more accurate three-dimensional impression, isosurface renderings that convert the volumetric data to surfaces was performed (Figure 4D–G). The isosurface render of Figure 4C is shown in Figure 4D. Blow ups of the neurons contained in boxes labeled e, f and g are shown in Figures 4E–G, respectively. The neurons in Figures 4E–G appeared to represent a continuum of nuclear polyadenylated mRNA staining. Where the neurons in 4E showed normal nuclear polyadenylated mRNA staining with nuclear speckles, the total nuclear polyadenylated mRNA staining was less in neuron 4F, and absent in the neurons of 4G. However as seen in the surface reconstruction of Figure 4F, the apparent polyadenylated mRNA nuclear staining was in fact the cytoplasm outside of the nucleus, and the volume inside of the nucleus was devoid of polyadenylated mRNA staining.

Cortical polyadenylated mRNA staining following focal cerebral ischemia

We present here, to the best of our knowledge, the first description of polyadenylated mRNA staining following focal cerebral ischemia. Our description here is abbreviated and a more thorough study will be forthcoming36. Figure 5A shows an orthographic projection (4 slices, z depth = 1.4 microns) of layer II neurons in sham-operated controls. Figure 5B shows a three-dimensional volumetric reconstruction of a single layer II neuron from a sham animal. Here, the cytoplasmic polyadenylated mRNA staining is false colored in green hues, and the polyadenylated mRNA nuclear staining in orange hues. The cytoplasmic polyadenylated mRNA staining is homogenous and smooth, similar to what we previously reported in control hippocampal neurons16. Following 4 hours of middle cerebral artery occlusion-induced unilateral ischemia, we observed prominent mRNA granules in the cytoplasm of layer II neurons of the ipsilateral cerebral cortex (Figure 5C). The cortical area from which Figure 5C is derived is shown by the box in the green area of Figure 5E. The green area marks the extent for which neurons, mainly of layers II and III, showed mRNA granules. A volumetric representation of a 4 hour ischemic layer II neuron is shown in Figure 5D (z depth = 1.4 microns). While the nuclear staining (orange) is similar to sham-operated controls, the polyadenylated mRNA cytoplasmic distribution can be seen to form a prominent and distinct granular distribution, the mRNA granules. As can be readily seen comparing Figure 5C to 5A, there was no change in nuclear polyadenylated mRNA staining after 4 hour middle cerebral artery occlusion as compared to controls.

While polyadenylated mRNA staining revealed shrunken and distorted neurons in what would have become the core area in layer VI (inset, Figure 5C; image derived from the area designated by the box in the red area of Figure 5E), we did not observe a lack of 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride staining in the 4 hour middle cerebral artery occlusion samples (Figure 5F, 4hI). However, 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride staining for the 4 hour middle cerebral artery occlusion samples did appear somewhat paler than sham operated controls (non-ischemic controls, Figure 5F) suggesting evolution of a core region. Following 2 hour middle cerebral artery occlusion and 24 hour reperfusion in the Long Evans rats, a core area devoid of 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride staining did occur (data not shown).

Cortical polyadenylated mRNA staining following global ischemia and reperfusion

Our initial report of mRNA granules16 used a normothermic 10 minute global ischemia period and extensively described hippocampal neurons. In that report we mentioned the occurrence of mRNA granules in cortical neurons following 10 minutes global ischemia but presented no data. Here, again to our knowledge, we present the first visualization of mRNA granules in cerebral cortical neurons of layer II of the rat following 10 minutes global brain ischemia and 1 hour reperfusion (Figure 6A). Essentially all neurons of layer II showed evidence of mRNA granules. Figures 6B and 6C show volumetric renderings of a single neuron (36 slices, z depth = 12.6 microns), with the same false color scheme as used in Figure 5. Figure 6C is a 90 degree rotation about the x-axis of Figure 6B, showing almost the entirety of the neuron's cell body. The mRNA granules occupied the entire cytoplasm. The nuclear polyadenylated mRNA staining resembled that of controls (e.g. as in Figure 5B). After 10 minutes global ischemia, there was no evidence of a generalized decrease in nuclear polyadenylated mRNA staining.

Figure 6.

Polyadenylated mRNA fluorescence in situ hybridization of cortical layer II following global cerebral ischemia. (A) Orthographic projection (63× oil immersion) of layer II (LII) following 10 minutes global ischemia and 1 hour reperfusion (10I/60R). (B) Volumetric three-dimensional reconstruction of the layer II neuron circled in A, false colored as in Figures 5B and D. Orange box marks extent of three-dimensional volume. (C) 90 degree rotation along x-axis of image in B is depicted. (D) Orthographic projection (63× oil immersion) of layer II following 15 minutes global ischemia and 1 hour reperfusion (15I/60R). Arrow points to a shrunken neuron displaying ischemic cell change. (E) Volumetric three-dimensional reconstruction of the layer II neuron circled in D, false colored as in B and C. Orange box marks extent of three-dimensional volume. (F) Superimposition of volumetric and isosurface renderings of circled neuron in D illustrating empty nuclear volume. Axes on three-dimensional reconstructions show orientations.

However, following 15 minutes global ischemia and 1 hour reperfusion, layer II neurons took on a considerably different appearance (Figure 6D). The neurons were somewhat more distorted and shrunken relative to those after 10 minutes global ischemia. There was not widespread loss of cortical neurons evident after 15 minutes global brain ischemia and 60 minutes reperfusion, as was seen with the endothelin 1 treatment. The cytoplasmic polyadenylated mRNA staining showed evidence of mRNA granulation. In addition, a clear decrease in nuclear polyadenylated mRNA staining was apparent in the 15 minutes global brain ischemia and 60 minutes reperfusion group (compare Figures 6A and 6D). A three-dimensional volumetric rendering of a layer II neuron after 15 minutes global brain ischemia and 60 minutes reperfusion is shown in Figure 6E (27 slices, z depth = 9.45 microns) in which the granular nature of the cytoplasmic polyadenylated mRNA staining is apparent. The accompanying isosurface rendering in Figure 6F clearly shows the hollow nucleus of the neuron, resembling that seen following endothelin 1 treatment (compare Figure 6F to 4F).

A gradation of loss of polyadenylated mRNA nuclear staining after 15 minutes global ischemia

Careful z-stack analysis of the 15 minutes global brain ischemia and 60 minutes reperfusion samples allowed us to discern a graded decrease in polyadenylated mRNA nuclear staining. Figure 7A shows a portion of an orthographic projection derived from a 44-slice z-stack (z depth = 15.4 microns) of layer II neurons. The three neurons labeled b, c and d were captured at approximately the same z depth in this stack, and all three neurons displayed similar intensities of granulated cytoplasmic polyadenylated mRNA staining, so that differences in polyadenylated mRNA nuclear staining could not be attributed to the penetration depth of the probe. Three-dimensional volumetric reconstructions through the middle 5 microns of each neuron were constructed (Figures B-1, C-1, and D-1). The graded decrease in nuclear polyadenylated mRNA staining is readily visible in these cross-sections, where a decrease in the staining intensity of the nuclear speckles is apparent. These impressions were substantiated by isosurface renderings where the cytoplasmic shell was rendered in a different color from the nuclear polyadenylated mRNA staining (Figures B-2, C-3 and D-2). Here, the decrease in surface area of nuclear polyadenylated mRNA staining (the blue surface) is apparent. Figures B-3, C-3, and D-3 overlay the volumetric and isosurface renderings to show how they register. Thus, the loss of nuclear polyadenylated mRNA staining formed a gradation that reflected a progressive decrease in the polyadenylated mRNA staining of the nuclear speckles.

Figure 7.

Loss of nuclear polyadenylated mRNA staining is graded following 15 minutes global ischemia. (A) Orthographic projection (63× oil immersion) of layer II (LII) following 15 minutes global ischemia and 1 hour reperfusion (15I/60R). Three-dimensional reconstructions of neurons b, c and d are shown below in respective columns. (B-1, C-1, D-1) False-colored volumetric renderings of neurons are shown in b, c and d, respectively. (B-2, C-2, D-2) Isosurface renderings of neurons are illustrated in b, c and d, respectively. Gold surfaces mark outer shell of cytoplasm, blue surfaces mark entire nuclear volume. (B-3, C-3, D-3) Registration of volumetric and isosurface renderings are illustrated. Orange boxes mark extent of volumes, axes show orientations.

Fluoro-Jade staining of samples

Fluoro-Jade staining is used as a marker of degenerating neurons37. We used Fluoro-Jade staining to further characterize cell injury phenotypes induced by endothelin 1 or brain ischemia (Figure 8). Surprisingly, blood vessels were a prominent staining target after endothelin 1 treatment (Figures 8A and B). Such blood vessel staining by Fluoro-Jade did not occur in the middle cerebral artery occlusion or global ischemia samples, suggesting that endothelin 1 acted as a stressor on vascular elements. High power photomicrographs of Fluoro-Jade stained blood vessels revealed a striated pattern suggestive of smooth muscle cells associated with cerebral arteries (Figure 8B), a well-established target of endothelin 138.

Figure 8.

Fluoro-Jade (FJ) staining after endothelin 1 treatment or middle cerebral artery occlusion. (A) 10× photomicrograph of FJ stained coronal section of cerebral cortex after 400 pg endothelin 1. (B) 40× photomicrograph of FJ stained cerebral cortex after 400 pg endothelin 1 showing vascular staining. (C) 10× photomicrograph of FJ stained coronal section of cerebral cortex after 800 pg endothelin 1. (D) 40× photomicrograph of FJ stained cerebral cortex after 800 pg endothelin 1 showing disintegrating neuropil. (E) 40× photomicrograph of FJ stained cerebral cortex after 2 hours middle cerebral artery occlusion and 24 hours reperfusion showing disintegrating neuropil. (F) FJ staining of hippocampal CA1 near endothelin 1 (400 pg) injection site. Pyramidal layer of CA1 is marked by dashed white lines. (G) Photomicrograph (63× oil immersion objective) of polyadenylated mRNA fluorescence in situ hybridization staining of FJ-reactive CA1 pyramidal cell layer marked by red box labeled “g” in panel F, showing lack of nuclear staining in CA1 pyramidal neurons. (H) Photomicrograph (63× oil immersion) of polyadenylated mRNA fluorescence in situ hybridization staining of FJ-refractory CA1 pyramidal cell layer marked by red box labeled “h” in panel F showing the control pattern of polyadenylated mRNA staining.

We also observed staining of nuclei in areas that were devoid of cell staining by polyadenylated mRNA fluorescence in situ hybridization. Figure 8C illustrates the patchy distribution of neuronal loss after 800 pg endothelin 1. The high-power photomicrograph of Figure 8D shows a disintegrating neuropil with a “spongy” appearance in which are embedded Fluoro-Jade responsive nuclei which are highly shrunken, again after 800 pg endothelin 1. These images resemble the core region of layer VI produced by 2 hours middle cerebral artery occlusion ischemia followed by 24 hours reperfusion (Figure 8E), in which the neuropil also appears “spongy” and shrunken neuronal nuclei respond to Fluoro-Jade.

Finally, we consistently observed the nuclei of hippocampal CA1 neurons under the site of endothelin 1 injection to respond to Fluoro-Jade (Figure 8F). Interestingly, the Fluoro-Jade responsive CA1 neurons were devoid of nuclear polyadenylated mRNA staining (Figure 8G). However, adjacent CA1 neurons that were unresponsive to Fluoro-Jade (Figure 8H) showed normal polyadenylated mRNA staining resembling control CA116.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we have used high resolution, polyadenylated mRNA staining as a type of “functional” histological marker. We previously showed that the appearance of mRNA granules in post-ischemic neurons correlated with an inhibition of in vivo protein synthesis below control levels16. The mRNA granules also failed to colocalize with ribosomal protein S616, a marker of the small ribosomal subunit, reinforcing the link between mRNA granules and protein synthesis inhibition. We have suggested that the reversible inhibition of protein synthesis in post-ischemic neurons is a marker of the transient genetic reprogramming of post-ischemic neurons to a stress response phenotype to abate and repair damage wrought by ischemia and reperfusion17. Thus, we undertook the present set of studies to assess for the presence of mRNA granules as a marker of stress response reprogramming under a wider variety of ischemic conditions including longer global ischemia, focal ischemia, and following endothelin 1 treatment.

mRNA granules

Consistent with our previous observations16, mRNA granules occurred in the neurons following 10 minutes global brain ischemia and 60 minutes reperfusion, and also following 4 hours middle cerebral artery occlusion ischemia with no reperfusion. In neither of these conditions was a change in nuclear polyadenylated mRNA staining apparent. The presence of neuronal mRNA granules under these two conditions suggests these neurons are experiencing protein synthesis inhibition in the service of reprogramming to a stress response phenotype. This conclusion is supported by: (1) the fact that 10 minutes of global ischemia with the 2 hours middle cerebral artery occlusion ischemia and 24 hours reperfusion model does not induce widespread cortical neuronal death39, and (2) that the location of the mRNA granule-containing neurons following 4 hours middle cerebral artery occlusion (Figure 5E, green area) is well outside of the core region, consistent with previous studies showing HSP70, FOS and other stress response protein expression in this cortical area following focal ischemia40,41,42. We also observed mRNA granules after 15 minutes global brain ischemia and 60 minutes reperfusion which in some cases co-occurred with loss of nuclear polyadenylated mRNA staining (Figure 6D–F and Figure 7). We consider the significance of this observation below.

Endothelin 1, apparent graded blood flow reduction, and mRNA granules

Inhibition of protein synthesis has been shown to occur after blood flow reductions to about 0.55 ml/gm/min43 which we observed at 400 pg endothelin 1 (Figure 1). We sought to confirm whether mRNA granule formation occurred at the threshold of protein synthesis inhibition. However, we did not observe mRNA granules at any endothelin 1 dose. Our histological results suggest an explanation for this apparent discrepancy. We observed discreet areas of damaged cerebral cortex interspersed amongst regions showing little or no damage (e.g. Figure 4A), and damaged area showed a trend of increasing as a function of endothelin 1 dose (Table 1). Such heterogeneous damage implies that blood flow reduction was equally heterogeneous. The apparent graded decrease in blood flow with endothelin 1 dose can be explained by an increasing recruitment of cortical areas with little or no blood flow, corresponding to the increased area of cortical damage (Table 1). The magnetic resonance imaging measurements would then represent averages of these heterogeneous blood flow patterns over the volumes used for detection. Mechanistically, this would imply that endothelin 1 affected discreet blood vessels differentially. Once a vessel became constricted by endothelin 1, blood flow would be reduced in that vessel, which may have limited the bulk flow of endothelin 1 throughout the vasculature.

Thus, endothelin 1 proved unsuitable to generate a homogeneous graded decrease in cerebral blood flow, preventing us from using endothelin 1 as a means to assess if the blood flow threshold for the formation of mRNA granules was the same as that which induces the inhibition of protein synthesis. While we were unsuccessful in this regard, the heterogeneous patterns of endothelin 1 damage proved fortuitous by generating a novel pattern of loss of nuclear polyadenylated mRNA staining in some post-ischemic neurons.

Loss of polyadenylated mRNA nuclear staining

We report here the novel observation of the loss of polyadenylated mRNA nuclear staining. This occurred after endothelin 1 treatment at all doses (Figure 3H, Figures 4F and G) but cannot be specific to endothelin 1 treatment because it also occurred following 15 minutes global brain ischemia and 60 minutes reperfusion global ischemia (Figures 6D–F). There are at least three possible functional interpretations of this observation and these are not necessarily mutually exclusive. A graded loss of nuclear speckles could represent: (1) a graded decrease in transcription of new mRNAs, and/or (2) a graded decrease in processing of nascent transcripts (e.g. addition of the polyadenylated tail), and/or (3) a graded increase in degradation of nascent transcripts within the nucleus. The present study provides no direct means to distinguish these possibilities.

There is a surprising dearth of studies of overall mRNA metabolism following cerebral ischemia and reperfusion. Yanagihara observed suppression of RNA polymerase activity following 3 hours reperfusion after 30 minutes carotid artery occlusion in gerbils44. Maruno and Yanagihara reported loss of total mRNA at 1 day following 10 minutes carotid artery occlusion in gerbils45. However, Matsumoto et al failed to find a decrease in nuclear mRNA during reperfusion after 15 minutes hindbrain ischemia46. Application of biochemical methods in the present study would have been problematic given the heterogeneous distribution of the cells showing loss of polyadenylated mRNA nuclear staining dispersed amongst cells with polyadenylated mRNA nuclear staining (e.g. Figures 4A and 4B).

There is abundant evidence of DNA alterations following brain ischemia and reperfusion including fragmentation47,48 and chromatin condensation49,50,51. Loss of DNA structural and functional integrity would be expected to interfere with mRNA transcription and/or processing. It is therefore possible that loss of nuclear polyadenylated mRNA staining is related to alterations in nuclear DNA in post-ischemic neurons. The details of this relationship remain to be determined.

Polyadenylated mRNA staining in relation to post-injury neuronal phenotypes

Different classes of necrotic post-ischemic phenotypes have been defined on the basis of morphological criteria, for which ischemic cell change is the most prevalent52. Ischemic cell change is characterized by shrinkage of the nucleus and cytoplasm, cellular distortion, acidophilia and nuclear pyknosis52,54. Following endothelin 1 treatment, the areas we designated as having the greatest degree of damage showed abundant “apparent” ischemic cell change. We say “apparent” because we did not here use H & E staining, but base this identification on the fact that neurons were shrunken and distorted (Figures endothelin 1 and 3F). On this basis we also saw evidence of occasional ischemic cell change following 4 hours focal ischemia (arrows, Figure 4C) or after 15 minutes global brain ischemia and 60 minutes reperfusion (arrow, Figure 6D). Generally, the highly shrunken ischemic cell change neurons had a polyadenylated mRNA staining pattern reminiscent of controls, albeit in a distorted fashion. Given the shrunken nature of the cell cytoplasm, we could not unambiguously determine if the ischemic cell change cells contained cytoplasmic mRNA granules. However, the shrunken cells generally retained polyadenylated mRNA nuclear staining resembling nuclear speckles (e.g. arrows, Figures endothelin 1 and 3F).

In contrast to cells apparently in the ischemic cell change stage, polyadenylated mRNA staining distinguished other cell phenotypes that were not massively shrunken, and which may have been previously described using other staining methods. For example, Petito et al (1997), using 10 minutes of 4 vessel occlusion global ischemia in rat, described post-ischemic changes in CA1 at 1 day reperfusion with “mild nuclear swelling”53. However, this conclusion was qualitative and nuclear diameters were not measured. We observed that mRNA granulation resulted in an apparent condensation of the cytoplasmic area (compare Figure 5A to 5C), with a resulting increase in total cell area taken up by the nucleus, suggesting Petito et al (1997) may have observed cells with condensed cytoplasm instead of “mild nuclear swelling”. Rosenblum also describes eosinophilic neurons that are not shrunken, but have distinguishable changes such as altered nuclear appearance54. High resolution analysis using polyadenylated mRNA staining provides a new window onto such previously identified morphological changes in non-shrunken post-ischemic neurons.

Relationships between polyadenylated mRNA-identified phenotypes

In the present study, we observed five distinguishable phenotypes in layer II cortical neurons. These are summarized and labeled as phenotypes A–E in Figure 9. Do these phenotypes reflect different stages of the same injury process or different and parallel processes?

Figure 9.

Summary of layer II neuronal phenotypes identified by polyadenylated mRNA fluorescence in situ hybridization. Phenotype A is the normal polyadenylated mRNA staining pattern of unaffected (control) neurons. Phenotype B showed only cytoplasmic mRNA granules. Phenotype C showed mRNA granules in the cytoplasm and loss of nuclear polyadenylated mRNA staining. Phenotype D showed no mRNA granules and loss of nuclear polyadenylated mRNA staining. Phenotype E consisted of shrunken “apparent” ischemic cell change cells. Experimental group (“Conditions”) abbreviations as defined in the text. For cytoplasmic polyadenylated mRNA staining, “homogeneous” refers to the diffuse cytoplasmic polyadenylated mRNA staining excluding stress granules and “granular” refers to mRNA granules. “Speckles” refers to nuclear speckles identified by polyadenylated mRNA staining. “na”, not applicable; “nd”, not determined.

Phenotypes B and C appear to reflect a phenotypic sequence that occurred with increasing ischemic intensity. Ten minutes ischemia followed by 60 minutes reperfusion and 4 hours middle cerebral artery occlusion ischemia and 24 hours reperfusion does not kill layer II neurons39, consistent with our interpretation that mRNA granule formation (phenotype B) reflects the shift to a protective stress response phenotype17. With 15 minutes global brain ischemia and 60 min reperfusion, loss of polyadenylated mRNA nuclear staining occurred in addition to mRNA granule formation (phenotype C). Since 15 minutes of global ischemia is more intense of an insult than 10 minutes, loss of polyadenylated mRNA nuclear staining is obviously an indicator of a greater degree of insult than the formation of the mRNA granules.

The endothelin 1 samples showed that loss of nuclear polyadenylated mRNA staining can occur in the absence of mRNA granule formation (phenotype D). Such a “double dissociation” indicates mRNA granules and loss of polyadenylated mRNA staining are mediated by independent processes. Since loss of polyadenylated mRNA nuclear staining occurred with the more intense global insult, loss of polyadenylated mRNA nuclear staining may, as discussed above, be a marker of cellular damage, as opposed to mRNA granules marking a protective response.

A key issue unresolved by the present study is whether phenotypes C and D, both of which displayed loss of nuclear polyadenylated mRNA staining, are reversible phenotypes that can recover, or if these are early stages of non-shrunken neurons irreversibly committed to cell death. Lack or loss of nuclear polyadenylated mRNA staining in the apparent ischemic cell change cells (phenotype E, Figure 9), and their co-occurrence with the other phenotypes, suggests that processes leading to ischemic cell change occur in parallel to those leading to the other non-shrunken phenotypes. The delayed neuronal death of hippocampal CA1 neurons does not include the loss of polyadenylated mRNA nuclear staining16. Thus, while loss of nuclear polyadenylated mRNA staining may be a marker of cell damage, it is not obligate for the delayed neuronal death of CA1 neurons. If loss of nuclear polyadenylated mRNA staining is a marker of eventual cell death, it would represent a different mode of cell death from CA1 delayed neuronal death. Future studies must address the relationship between loss of nuclear polyadenylated mRNA staining and cell death.

Conclusion

The present study evaluated polyadenylated mRNA staining as a “functional” histological marker of post-ischemic phenotypes. It further illustrated the utility of polyadenylated mRNA fluorescence in situ hybridization staining for characterizing the response of neurons under a variety of injury conditions. We were unable to use endothelin 1 intraventricular injection to determine the threshold of mRNA granule formation. However, we identified two previously undescribed post-ischemic phenotypes; both characterized by loss of nuclear polyadenylated mRNA staining (Figure 9, phenotypes C and D). The functional significance and contribution, if any, to post-ischemic cell death remains to be determined. Nonetheless, the present work provides additional insight into the complexity of post-ischemic phenotypes, and supports a notion whereby post-ischemic phenotypes derive from a competition between protective stress responses and destructive damage mechanisms.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Jie Wang for her assistance with the global ischemia and reperfusion model. We also thank Drs. E. Mark Haacke and Yimin Shen for their technical assistance with ASL-Magnetic resonance imaging. This work was sponsored by NIH Grant No. NS-057167 (D.J.D.) and NS-064976 (C.W.K.) from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wei L, Ying DJ, Cui L, Langsdorf J, Yu SP. Necrosis, apoptosis and hybrid death in the cortex and thalamus after barrel cortex ischemia in rats. Brain Res. 2004;1022(1–2):54–61. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.06.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.MacManus JP, Buchan AM. Apoptosis after experimental stroke: fact or fashion? J Neurotrauma. 2000;17(10):899–914. doi: 10.1089/neu.2000.17.899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Portera-Cailliau C, Price DL, Martin LJ. Non-NMDA and NMDA receptor-mediated excitotoxic neuronal deaths in adult brain are morphologically distinct: further evidence for an apoptosis-necrosis continuum. J Comp Neurol. 1997;378(1):88–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hossmann K-A. Pathophysiological basis of translational stroke research. Folia Neuropathol. 2009;47:213–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DeGracia DJ. Ischemic damage and neuronal stress responses: Towards a systematic approach with implications for therapeutic treatments. In: Wang DQ, Ying W, editors. New Frontiers in Neurological Research. Research Signpost; Kerala, India: 2008. pp. 235–264. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Endres M, Engelhardt B, Koistinaho J, Lindvall O, Meairs S, Mohr JP, Planas A, Rothwell N, Schwaninger M, Schwab ME, Vivien D, Wieloch T, Dirnagl U. Improving outcome after stroke: overcoming the translational roadblock. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2008;25:268–278. doi: 10.1159/000118039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lo EH. A new penumbra: transitioning from injury into repair after stroke. Nat Med. 2008;14:497–500. doi: 10.1038/nm1735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nowak TS., Jr. Protein synthesis and the heart shock/stress response after ischemia. Cerebrovasc Brain MetabRev. 1990;2:345–366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sharp FR, Massa SM, Swanson RA. Heat-shock protein protection. Trends Neurosci. 1999;22:97–99. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(98)01392-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paschen W. Disturbances of calcium homeostasis within the endoplasmic reticulum may contribute to the development of ischemic-cell damage. Med Hypotheses. 1996;47:283–288. doi: 10.1016/s0306-9877(96)90068-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DeGracia DJ, Kumar R, Owen CR, Krause GS, White BC. Molecular pathways of protein synthesis inhibition during brain reperfusion: implications for neuronal survival or death. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2002;22:127–141. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200202000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kauppinen TM, Swanson RA. The role of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 in CNS disease. Neuroscience. 2007;145(4):1267–1272. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Luo Y, Ji X, Ling F, Li W, Zhang F, Cao G, Chen J. Impaired DNA repair via the base-excision repair pathway after focal ischemic brain injury: a protein phosphorylation-dependent mechanism reversed by hypothermic neuroprotection. Front Biosci. 2007;12:1852–1862. doi: 10.2741/2193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DeGracia DJ. Towards a dynamical network view of brain ischemia and reperfusion. Part I: Background and preliminaries. J Exp Stroke Transl Med. 2010;3:59–71. doi: 10.6030/1939-067x-3.1.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DeGracia DJ. Towards a dynamical network view of brain ischemia and reperfusion. Part II: Post-ischemic neuronal state space. J Exp Stroke Transl Med. 2010;3:72–89. doi: 10.6030/1939-067x-3.1.72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jamison JT, Kayali F, Rudolph J, Marshall M, Kimball SR, DeGracia DJ. Persistent redistribution of poly-adenylated mRNAs correlates with translation arrest and cell death following global brain ischemia and reperfusion. Neuroscience. 2008;154(2):504–520. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.03.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.DeGracia DJ, Jamison JT, Szymanski JJ, Lewis MK. Translation arrest and ribonomics in post-ischemic brain: layers and layers of players. J Neurochem. 2008;106(6):2288–2301. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05561.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yanagisawa M, Kurihara H, Kimura S, Goto K, Masaki T. A novel peptide vasoconstrictor, endothelin, is produced by vascular endothelium and modulates smooth muscle Ca2+ channels. J. Hypertens. 1988;(Suppl 6):S188–S191. doi: 10.1097/00004872-198812040-00056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kreipke CW, Schafer PC, Rossi NF, Rafols JA. Differential effects of endothelin receptor A and B antagonism on cerebral hypoperfusion following traumatic brain injury. Neurol Res. 2010;32(2):209–214. doi: 10.1179/174313209X414515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Salom JB, Torregrosa G, Alborch E. Endothelins and the cerebral circulation. Cerebrovasc Brain Metab Rev. 1995;7(2):131–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reid JL, Dawson D, Macrae IM. Endothelin, cerebral ischaemia and infarction. Clin Exp Hypertens. 1995;17(1–2):399–407. doi: 10.3109/10641969509087080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sharkey J, Butcher SP. Characterisation of an experimental model of stroke produced by intracerebral microinjection of endothelin 1 adjacent to the rat middle cerebral artery. J Neurosci Methods. 1995;60(1–2):125–131. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(95)00003-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Windle V, Szymanska A, Granter-Button S, White C, Buist R, Peeling J, Corbett D. An analysis of four different methods of producing focal cerebral ischemia with endothelin 1 in the rat. Exp Neurol. 2006;201(2):324–334. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2006.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Paxinos G, Watson C. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. 5th ed Elsevier Academic Press; Amsterdam: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith ML, Bendek G, Dahlgren N, Rosen I, Wieloch T, Siesjo BK. Models for studying long-term recovery following forebrain ischemia in the rat 2 A 2-vessel occlusion model. Acta Neurol Scand. 1984;69:385–401. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1984.tb07822.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.DeGracia DJ, Rudolph J, Roberts GG, Rafols JA, Wang J. Convergence of stress granules and protein aggregates in hippocampal CA1 at later reperfusion following global brain ischemia. Neuroscience. 2007;146(2):562–572. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.01.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roberts GG, Di Loreto MJ, Marshall M, Wang J, DeGracia DJ. Hippocampal cellular stress responses after global brain ischemia and reperfusion. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2007;9(12):2265–2275. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.1786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hatashita T, Ito M, Miyaoka M, Ishii S. Chronological alterations of regional cerebral blood flow, glucose utilization, and edema formation after focal ischemia in hypertensive and normotensive rats. Significance of hypertension. Adv Neuro. 1990;52:29–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Levy J, Zhu Z, Dunbar JC. The effect of global brain ischemia in normal and diabetic animals: the influence of calcium channel blockers. Endocrine. 2004;25(2):91–95. doi: 10.1385/ENDO:25:2:091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li ZG, Britton M, Sima AA, Dunbar JC. Diabetes enhances apoptosis induced by cerebral ischemia. Life Sci. 2004;76(3):249–262. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2004.03.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rizk NN, Rafols J, Dunbar JC. Cerebral ischemia induced apoptosis and necrosis in normal and diabetic rats. Brain Res. 2005;1053(1–2):1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schmued LC, Albertson C, Slikker W., Jr. Fluoro-Jade: a novel fluorochrome for the sensitive and reliable histochemical localization of neuronal degeneration. Brain Res. 1997;751(1):37–46. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(96)01387-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kayali F, Montie HL, Rafols JA, DeGracia DJ. Prolonged translation arrest in reperfused hippocampal CA1 is mediated by stress granules. Neuroscience. 2005;134:1223–1245. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.05.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Abramoff MD, Magelhaes PJ, Ram SJ. Image Processing with Image. J. Biophotonics International. 2004;11:36–42. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martone ME, Pollock JA, Jones YZ, Ellisman MH. Ultrastructural localization of dendritic messenger RNA in adult rat hippocampus. J Neurosci. 1996;16:7437–7446. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-23-07437.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lewis MK, Rizk N, Dunbar J, DeGracia DJ. Characterization of poly-adenylated mRNAs following focal cerebral ischemia. 2010 In preparation. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schmued LC, Stowers CC, Scallet AC, Xu L. Fluoro-Jade C results in ultra high resolution and contrast labeling of degenerating neurons. Brain Res. 2005;1035(1):24–31. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.11.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mima T, Yanagisawa M, Shigeno T, Saito A, Goto K, Takakura K, Masaki T. Endothelin acts in feline and canine cerebral arteries from the adventitial side. Stroke. 1989;20(11):1553–1556. doi: 10.1161/01.str.20.11.1553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu CL, Ge P, Zhang F, Hu BR. Co-translational protein aggregation after transient cerebral ischemia. Neuroscience. 2005;134(4):1273–1284. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kokubo Y, Liu J, Rajdev S, Kayama T, Sharp FR, Weinstein PR. Differential cerebral protein synthesis and heat shock protein 70 expression in the core and penumbra of rat brain after transient focal ischemia. Neurosurgery. 2003;53(1):186–190. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000069023.01440.d6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sharp FR, Lu A, Tang Y, Millhorn DE. Multiple molecular penumbras after focal cerebral ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2000;20(7):1011–1032. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200007000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hossmann KA. Disturbances of cerebral protein synthesis and ischemic cell death. Prog Brain Res. 1993;96:161–177. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)63265-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hossmann KA. Pathophysiology and therapy of experimental stroke. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2006;26(7–8):1057–1083. doi: 10.1007/s10571-006-9008-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yanagihara T. Experimental stroke in gerbils: effect on translation and transcription. Brain Res. 1978;158(2):435–444. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(78)90686-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Maruno M, Yanagihara T. Progressive loss of messenger RNA and delayed neuronal death following transient cerebral ischemia in gerbils. Neurosci Lett. 1990;115(2–3):155–160. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(90)90447-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Matsumoto K, Yamada K, Hayakawa T, Sakaguchi T, Mogami H. RNA synthesis and processing in the gerbil brain after transient hindbrain ischaemia. Neuro Res. 1990;12:45–48. doi: 10.1080/01616412.1990.11739912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.MacManus JP, Fliss H, Preston E, Rasquinha I, Tuor U. Cerebral ischemia produces laddered DNA fragments distinct from cardiac ischemia and archetypal apoptosis. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1999;19(5):502–510. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199905000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.MacManus JP, Hill IE, Preston E, Rasquinha I, Walker T, Buchan AM. Differences in DNA fragmentation following transient cerebral or decapitation ischemia in rats. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1995;15(5):728–737. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1995.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kalimo H, Rehncrona S, Söderfeldt B, Olsson Y, Siesjö BK. Brain lactic acidosis and ischemic cell damage: 2. Histopathology. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1981;1(3):313–327. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1981.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kalimo H, Garcia JH, Kamijyo Y, Tanaka J, Trump BF. The ultrastructure of “brain death”. II. Electron microscopy of feline cortex after complete ischemia. Virchows Arch B Cell Pathol. 1977;25(3):207–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hossmann KA, Oschlies U, Schwindt W, Krep H. Electron microscopic investigation of rat brain after brief cardiac arrest. Acta Neuropathol. 2001;101(2):101–113. doi: 10.1007/s004010000260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lipton P. Ischemic cell death in brain neurons. Physiol Rev. 1999;79(4):1431–1568. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.4.1431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Petito CK, Torres-Munoz J, Roberts B, Olarte JP, Nowak TS, Jr, Pulsinelli WA. DNA fragmentation follows delayed neuronal death in CA1 neurons exposed to transient global ischemia in the rat. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1997;17(9):967–976. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199709000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rosenblum WI. Histopathologic clues to the pathways of neuronal death following ischemia/hypoxia. J Neurotrauma. 1997;14(5):313–326. doi: 10.1089/neu.1997.14.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]