Abstract

Vascular smooth muscle cell (VSMC) migration is an important cellular event in multiple vascular diseases, including atherosclerosis, restenosis, and transplant vasculopathy. Little is known regarding the effects of anti-inflammatory interleukins on VSMC migration. This study tested the hypothesis that an anti-inflammatory Th2 interleukin, interleukin-19 (IL-19), could decrease VSMC motility. IL-19 significantly decreased platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF)-stimulated VSMC chemotaxis in Boyden chambers and migration in scratch wound assays. IL-19 significantly decreased VSMC spreading in response to PDGF. To determine the molecular mechanism(s) for these cellular effects, we examined the effect of IL-19 on activation of proteins that regulate VSMC cytoskeletal dynamics and locomotion. IL-19 decreased PDGF-driven activation of several cytoskeletal regulatory proteins that play an important role in smooth muscle cell motility, including heat shock protein-27 (HSP27), myosin light chain (MLC), and cofilin. IL-19 decreased PDGF activation of the Rac1 and RhoA GTPases, important integrators of migratory signals. IL-19 was unable to inhibit VSMC migration nor was able to inhibit activation of cytoskeletal regulatory proteins in VSMC transduced with a constitutively active Rac1 mutant (RacV14), suggesting that IL-19 inhibits events proximal to Rac1 activation. Together, these data are the first to indicate that IL-19 can have important inhibitory effects on VSMC motility and activation of cytoskeletal regulatory proteins. This has important implications for the use of anti-inflammatory cytokines in the treatment of vascular occlusive disease.

Keywords: vascular smooth muscle cell, heat shock protein 27, myosin light chain, cofilin, RhoA, Rac1

the etiology of multiple vascular diseases including atherosclerosis, restenosis, and allograft vasculopathy involve a localized inflammatory response in which endothelial cells and recruited inflammatory cells synthesize chemotactic factors. Vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMC) respond to many of these factors by switching from a quiescent, contractile to a synthetic phenotype capable of migration in response to these factors. VSMC migration from the media into the intima is a hallmark of this phenotypic switch and an integral cellular event of multiple vascular diseases leading to a loss of lumen diameter and vascular contractility (19, 40, 30). Luminal migration of such activated VSMC is one of the most critical cellular events in the development of intimal hyperplasia and represents a point of therapeutic intervention to attenuate several vascular diseases.

The molecular mechanisms of VSMC migration are well described and begin with engagement of growth factor and inflammatory cytokine receptor that transduce external ligand binding into internal biochemical events. In VSMC, soluble pro-migratory compounds are varied and include PDGF, basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF), and tumor necrosis factor (23, 30, 33). Many of the intercellular proteins involved in VSMC migration include activation of monomeric GTPases such as RhoA and Rac1, mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinases such as p38, and cytoskeletal and actin remodeling proteins such as cofilin, myosin light chain (MLC), and heat shock protein (HSP)27. Together, the coordinated activation of these proteins allows the smooth muscle cell to protrude lamellipodia, remodel actin, and allow the cell to migrate toward the chemotactic stimulus. Whereas the effects of proliferative and promigratory cytokines that induce VSMC migration have been well studied and well characterized, the cytokines that can reduce or attenuate this response are under characterized (10). In particular, there is very little and somewhat conflicting data available regarding effects of anti-inflammatory interleukins on VSMC migration. As examples, one report indicates that the prototypical anti-inflammatory interleukin-10 (IL-10) can inhibit VSMC migration (20), whereas another indicates that the pro-inflammatory interleukin IL-1β can also inhibit VSMC migration (7). Identification of cytokines that can decrease VSMC migration, particularly those that are locally and specifically expressed in response to inflammation or trauma, could lead to new therapies to attenuate many vascular diseases.

We previously reported that a recently described IL-10 family member interleukin-19 (IL-19) is expressed in injured, but not uninjured arteries, and in stimulated, but not quiescent VSMC (36). This was novel and unexpected because IL-19 expression was previously thought to be restricted to immune cells (8). IL-19 is considered to be an anti-inflammatory interleukin because in T-lymphocytes it promotes the Th2 (regulatory) rather than the Th1 (T helper) response (9, 24, 26). Our laboratory found that IL-19 had anti-proliferative effects on cultured VSMC, and IL-19 adenoviral gene transfer significantly reduced neointimal hyperplasia and proliferation of intimal VSMC in balloon angioplasty-injured rat carotid arteries (36). Addition of IL-19 to cultured VSMC reduces their proliferation and decreases abundance of proliferative and inflammatory proteins (36, 34). These are the only reports to date describing IL-19 expression and protective functions in VSMC.

Because migration is such an important part of multiple vascular diseases, it was important to investigate the effects and potential molecular mechanisms of IL-19 effects on VSMC migration. The overarching goal of this study is to determine whether IL-19 can negatively effect VSMC migration and define the components of the cellular machinery that are effected by IL-19. In this study we report that IL-19 can reduce VSMC chemotaxis, migration, and activation of several cytoskeletal regulatory proteins. Functional identification of cytokines common to immune and vascular cells has the potential to link inflammatory processes with vascular dysfunction. Understanding the cellular and molecular pathways of these anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-19 can open new therapeutic venues for coronary heart disease and restenosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and culture.

Primary human coronary artery VSMC (hVSMC) were obtained as cryopreserved secondary culture from Cascade (Portland, OR) and subcultured in growth medium as described previously (5). Cells from three different male donors (aged 18–25 years, passages 3–5) were used in the described studies. Recombinant IL-19 (100 ng/ml for all studies) and decreased platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF)-AB (40 ng/ml) was from R&D.

Cell spreading.

Spreading was performed as described (39). Briefly, hVSMC (105 cells/ml) were plated on glass coverslips in growth media. After adherence, medium was changed to contain 0.5% fetal calf serum (FCS). After 24 h, VSMC were incubated with PDGF or IL-19 for 30 min. Some cells were preincubated with IL-19 for 4 h and then incubated with PDGF for 30 additional minutes. VSMC were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized with 0.2% Triton-X 100. Rhodamine phalloidin was added to stain filamentous actin. Images were captured with an inverted microscope using epifluorescence. Cell spreading was calculated by tracing the cell and measuring the area using Image-Pro Plus software.

Cell migration and chemotaxis.

Analysis of chemotaxis was performed as described (34). Briefly, triplicate 6.5-mm-diameter Transwell Boyden chamber plates (Costar) with 8-μm polycarbonate membrane pore size were seeded with VSMC (20,000 cells per membrane) in medium containing 0.5% FCS. Forty nanograms of PDGF-AB were placed in the lower chamber, and cells were incubated for 4 h at 37°C, at which time cells were fixed and stained in Dif-Quick Cell Stain (American Hospital Supply). The upper layer was scraped free of cells. VSMC that had migrated to the lower surface of the membrane were quantitated by counting four high-powered fields per membrane. Experiments were performed in triplicate from three independent groups of VSMC. For directional migration, scratch wounding was performed as we previously described, and wound area was quantitated by image analysis (34). Briefly, hVSMC were grown to 80% confluence in the presence of FCS in a four-chamber slide in growth medium. A 2-mm uniform scratch was made using a cell scraper, which was cut to 2-mm size. The medium was replaced with medium plus PDGF-AB (40 ng/ml), IL-19, and for some samples, 2 μg/ml of either IL-19 or IL-20R-β neutralizing antibody. The chamber slide was then returned back to the cell culture incubator for 24 h to eliminate effects of proliferation. The slide was the fixed with paraformaldehyde and stained with hemotoxylin-eosin. Images were captured at ×4 magnification.

Rac1 and RhoA activation.

The pull-down assay was performed as we previously described to determine Rac1 activation (3). Briefly, hVSMC were serum starved in 0.1% FCS 48 h, challenged with 40 ng/ml PDGF for various times, and lysed in sample buffer (25 nM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl, 0.5 mM EGTA, 20 mM β-glycerophosphate, 0.5% Triton-X100, 5% glycerol, 10 mM NaF, 2 mM sodium vanadate, plus protease inhibitors). The volume of lysate was adjusted to normalize for equal concentrations of proteins and incubated with GST-PAK Sepharose for Rac1 and GST-Rhoteckin Sepharose (both from Cytoskeleton) for 2 h at 4°C. Only the activated (GTP) form of Rac1 bind the PAK protein and GTP form of Rho bind Rhoteckin. Beads were washed three times, bound proteins detected by Western blotting with Rac1 or Rho A antibody, and quantitated by densitometry of corresponding bands. Each experiment was performed at least three times.

Western blot analysis was performed as described (5). Briefly, hVSMC extracts were prepared as described (5) and lysates frozen until use. Membranes were incubated with a 1:3,000–5,000 dilution of primary antibody and a 1:5,000 dilution of secondary antibody. Antibody to total and phospho-specific HSP27, MLC, and cofilin were from Cell Signaling. Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), RhoA, and Rac1 antibody were from Neo Markers, and reactive proteins were visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham) according to manufacturer's instructions. Relative intensities of light emission were obtained by densiometric scanning of autoradiograms developed at several different exposures within the linear range of the film (Amersham Hyperfilm ECL). The relative intensity of each band was quantitated by scanning with the use of the NIH Image J densitometry program and normalized to total protein. Adenoviral RacV14 (40), a kind gift of Dr. Satoru Eguchi, was used to infect VSMC at 30 multiplicities of infection (MOI), adenoviral negative control LacZ (34) were infected at the same MOI with starvation begun 48 h postinfection.

Statistical analysis.

Results are expressed as means ± SE. Differences between groups were evaluated with the use of ANOVA, with the Newman-Keuls method applied to evaluate differences between individual mean values and by paired t-tests where appropriate, respectively. Differences were considered significant at a level of P < 0.05.

RESULTS

IL-19 reduces VSMC migration and wound healing.

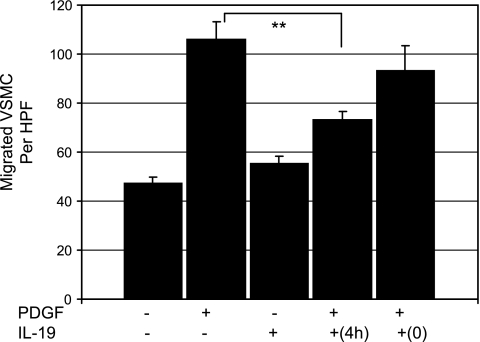

We hypothesized that IL-19 might regulate VSMC motility in response to chemotactic stimuli. hVSMC were treated with IL-19 for 4 h, trypsinized, and then seeded on Boyden chambers in the presence or absence of the potent chemotactic agent PDGF. Figure 1A shows that VSMC pretreated with IL-19 had significantly decreased migration in response to PDGF compared with those treated with PDGF alone (105.8 ± 7.6 vs. 73.4 ± 3.3 for PDGF and IL-19-pretreatd, PDGF-stimulated VSMC, respectively, P < 0.01, n = 3). IL-19 alone as a chemoattractant in the bottom chamber had no effect on VSMC migration, and IL-19 added at the same time as PDGF had no effect on migration. This shows that IL-19 pretreatment reduces VSMC chemotaxis in response to PDGF.

Fig. 1.

Interleukin (IL)-19 reduces human vascular smooth muscle cell (hVSMC) migration. hVSMC were seeded onto the top chamber of a modified Boyden chamber with or without medium containing 0.2% BSA, with or without 100 ng/ml IL-19, or 40 ng/ml PDGF as a positive control, in the lower chamber. Some VSMC were pretreated with IL-19 4 h before trypsinization and seeding in migration chambers (4h), and in others IL-19 was added at the same time as PDGF (0). Values are means from three experiments performed in triplicate from three independent groups of VSMC. **Significant difference of 4 h pretreated from PDGF control (P < 0.01).

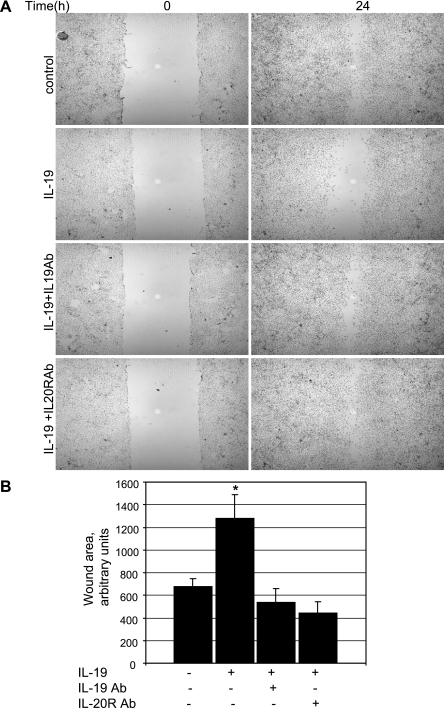

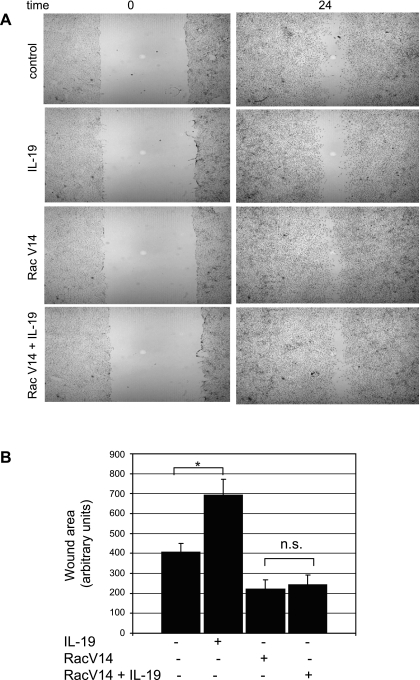

We also performed a scratch wound assay in which directional migration of VSMC monolayer's in the presence and absence of IL-19 could be assessed. Equal numbers of confluent VSMC were incubated in growth media containing PDGF and were scraped to create a 2-mm wide wound track devoid of cells. As additional controls, media from some samples contained IL-19 neutralizing antibody, and others contained antibody to the IL-20 receptor β chain, through which IL-19 signals (26). VSMC were fixed and stained 24 h later to avoid potential effects of PDGF on proliferation. Data presented in Fig. 2B demonstrates that IL-19-treated cells migrate into the wound more slowly than do untreated or control samples. Neutralizing antibody directed to IL-19 or IL-20R negates the inhibitory effect of IL-19. Together, these are the first data indicating that IL-19 can reduce motility of any cell type.

Fig. 2.

IL-19 reduces VSMC wound healing. A: scratch wounding in the presence or absence of 100 ng/ml IL-19, 2 μg/ml neutralizing antibody to IL-19, or antibody to IL-20 receptor. Cells were seeded in the presence of 10% FCS. After a single scratch, medium was replaced with medium plus platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF-AB) (40 ng/ml). Cells were stained with hematoxylin and are magnified ×40. This is representative of three independent experiments. B: quantitative analysis of scratch wound area from three different groups of treated VSMC. *Significant difference from 4 different slides of IL-19-treated versus untreated control (P < 0.05).

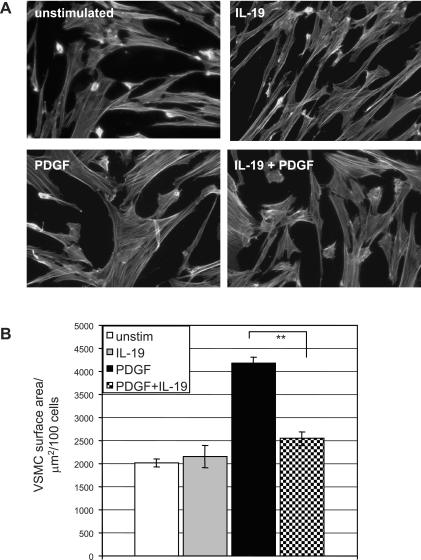

IL-19 reduces VSMC spreading. The decrease in migration suggested modulation of actin dynamics by IL-19. To determine whether IL-19 influenced cell spreading, hVSMC were plated on glass cover slides and allowed to adhere. The next day they were treated with IL-19 for 4 h and then PDGF was added for 30 min. After fixation and phalloidin staining, surface area of spreading cells was quantitated by image analysis. Figure 3 shows that IL-19-stimulated VSMC demonstrates significantly decreased cell spreading compared with untreated cells (4160 ± 146 vs. 2544 ± 156 μm2 for PDGF and IL-19 treated VSMC, respectively, P < 0.01, n = 3), a 43% decrease in area. The next series of experiments was designed to characterize the molecular mechanisms for these decreases in chemotaxis, migration, and spreading.

Fig. 3.

IL-19 reduces VSMC spreading. A: VSMC grown on glass coverslips were treated with IL-19 for 3 h or left untreated. Rhodamine phalloidin was added to stain filamentous actin. B: images were captured and calculated by tracing the cell and measuring the area using Image-Pro Plus software. Data shown are means ± SD of 100 cells from each population from three separate experiments. **Significant difference of IL-19 treated versus PDGF alone control (P < 0.05). Magnification ×400.

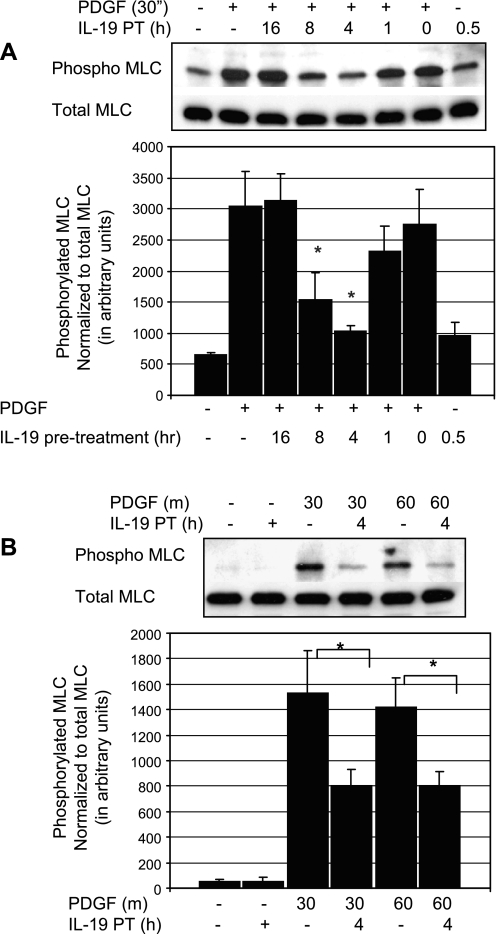

IL-19 inhibits phosphorylation of MLC.

An early event in smooth muscle cell (SMC) migration is phosphorylation of MLC, leading to actin remodeling (10, 13). Many chemotactic cytokines initiate migration by phosphorylation of MLC and MLCK inhibitors can block SMC migration (14, 17). In VSMC, MLC is rapidly phosphorylated and activated in response to FCS or PDGF (16, 18). To determine whether IL-19 inhibited or decreased MLC activation, VSMC were serum starved for 48 h, and after several different time points of IL-19 pretreatment followed by 30 min PDGF stimulation, lysates were examined by immunoblot. Figure 4A shows that IL-19 can significantly reduce activation of MLC by PDGF, with inhibition peaking at ∼4 h of pretreatment. This inhibition was further investigated by focusing on 4 h of IL-19 pretreatment and two different times of PDGF stimulation. We found that IL-19 could significantly inhibit phosphorylation of MLC by an average of 47.7% at 30 min PDGF stimulation (1534.0 ± 329 vs. 802.1 ± 129 for control and IL-19-treated cells, respectively; P < 0.01) and of 43.3% at 60 min PDGF stimulation (1408 ± 240 vs. 810 ± 177 for control and IL-19-treated cells, respectively; P < 0.05) (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

IL-19 inhibits phosphorylation of myosin light chain (MLC). A: representative immunoblot of time course of IL-19 pretreatment. To determine whether IL-19 inhibited or decreased MLC activation, VSMC were serum starved for 48 h, and after several time points of IL-19 pretreatment, VSMC were stimulated with PDGF, and lysates were examined for phosphorylation of MLC. B: inhibition was further investigated focusing on 4 h of IL-19 pretreatment and two different times of PDGF stimulation. Combined statistical analysis; values and means from four experiments using independently treated groups of VSMC (*P < 0.05 compared with non-IL-19-treated control).

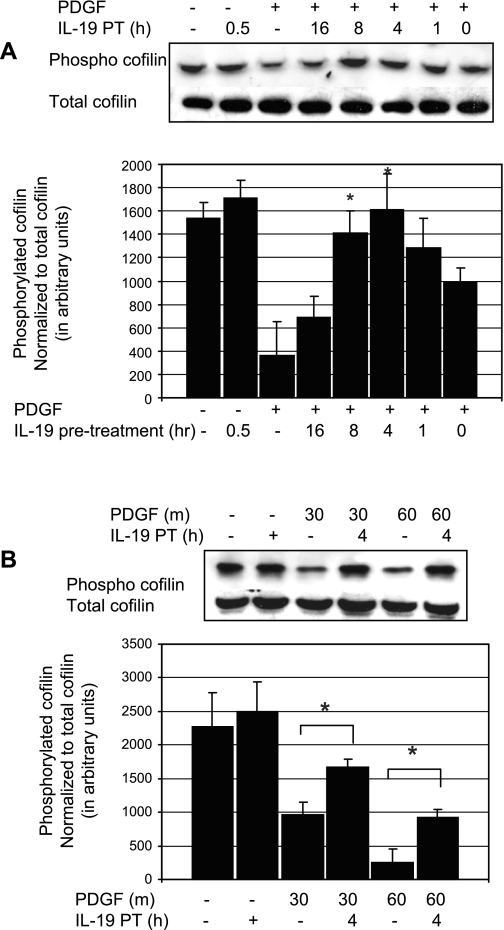

IL-19 inhibits dephosphorylation of cofilin.

In VSMC, cofilin undergoes a rapid dephosphorylation following PDGF stimulation, which maximizes at 30 min (32). Cofilin is activated by dephosphorylation, and the cofilin activation state was assayed by Western blot analysis with phospho-specific protein. To determine whether IL-19 inhibited or decreased cofilin activation, VSMC were serum starved for 48 h, and several time points of IL-19 pretreatment were examined. Figure 5A shows that IL-19 can significantly reduce activation of cofilin by PDGF, with inhibition peaking at ∼4 h of pretreatment. This inhibition was further investigated focusing on 4 h of IL-19 pretreatment and two different times of PDGF stimulation. We found that IL-19 could significantly inhibit dephosphorylation of cofilin by an average of 42% at 30 min PDGF stimulation (962.8 ± 190 vs. 1673.9 ± 122 for control and IL-19-treated cells, respectively; P < 0.05), and 73.0% at 60 min PDGF stimulation (247.9 ± 200 vs. 918.1 ± 123 control and IL-19-treated cells, respectively; P < 0.05) (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

IL-19 inhibits dephosphorylation of cofilin. A: representative immunoblot of time course of IL-19 pretreatment. To determine whether IL-19 inhibited or decreased MLC activation, VSMC were serum starved for 48 h, and after several time points of IL-19 pretreatment, VSMC were stimulated with PDGF, and lysates were examined for phosphorylation of cofilin. B: inhibition of dephosphorylation was further investigated focusing on 4 h of IL-19 pretreatment and two different times of PDGF stimulation. Combined statistical analysis; values and means from four experiments using independently treated groups of VSMC (*P < 0.05 compared with non-IL-19-treated control).

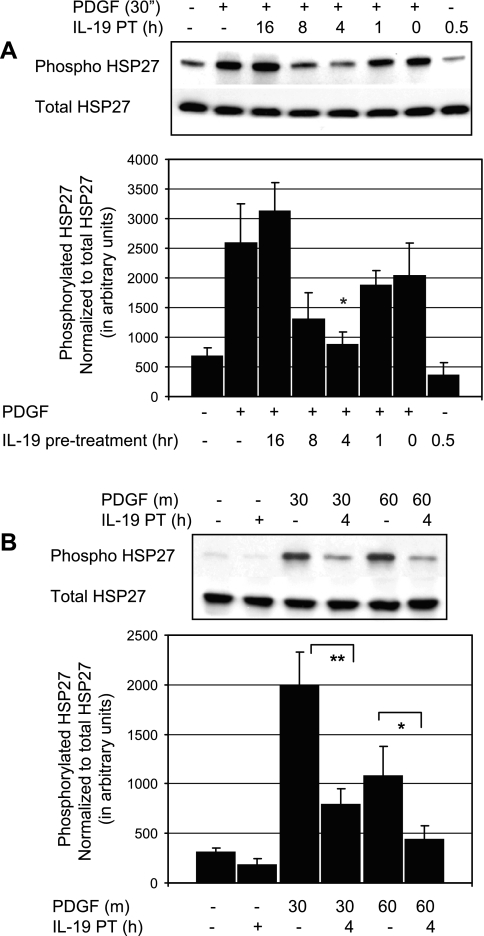

IL-19 inhibits phosphorylation of HSP27.

Cofilin activity is modulated by HSP27, and phosphorylation of HSP27 is involved in actin polymerization and plays an important role in the regulation of VSMC migration (10, 15, 28). To determine whether IL-19 inhibited or decreased HSP27 activation, VSMC were serum starved for 48 h, and several time points of IL-19 pretreatment were examined. HSP27 activation was assayed by Western blot analysis with phospho-specific protein. Figure 6A shows that IL-19 can significantly reduce activation of HSP27 by PDGF, with inhibition peaking at ∼4 h of pretreatment. Figure 6B shows that IL-19 can significantly reduce activation of HSP27 by PDGF by an average of 59.9% at 30 min PDGF stimulation (1984.8 ± 344 vs. 795.5 ± 155 for control and IL-19 treated cells, respectively; P < 0.01), and 59.6% at 60 min PDGF stimulation (1080.4 ± 301 vs. 436.9 ± 139 for control and IL-19-treated cells, respectively; P < 0.05).

Fig. 6.

IL-19 inhibits phosphorylation of heat shock protein (HSP)27. A: representative immunoblot of time course of IL-19 pretreatment. To determine whetehr IL-19 inhibited or decreased HSP activation, VSMC were serum starved for 48 h, and after several different time points of IL-19 pretreatment, VSMC were stimulated with PDGF, and lysates were examined for phosphorylation state of HSP27. B: inhibition of HSP27 phosphorylation was further investigated focusing on 4 h of IL-19 pretreatment and two different times of PDGF stimulation. Combined statistical analysis; values and means from four experiments using independently treated groups of VSMC (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 compared with non-IL-19-treated control).

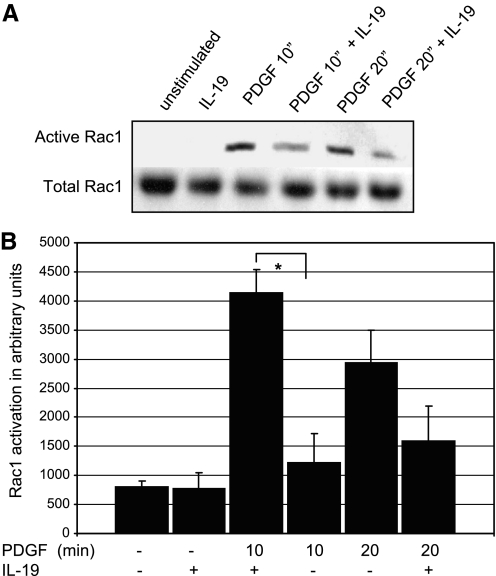

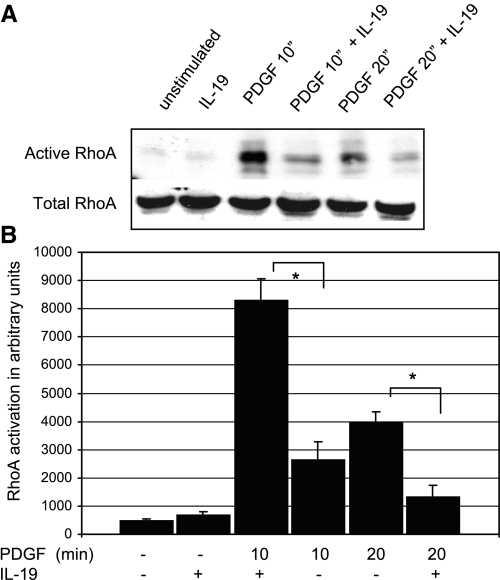

IL-19 inhibits monomeric GTPase activity.

Cytoskeletal organization, cell spreading, VSMC migration, and cell movement in response to PDGF is mediated by activation of the small GTPases Rac1 and Rho A (10, 4, 14). Regulators of cytoskeletal dynamics are among the many downstream effects of activation of these GTPases (4, 13). To determine IL-19 effects on activity of these small GTPases, VSMC were serum starved for 48 h, pretreated with IL-19 for 4 h, and then stimulated with PDGF for 10 and 20 min. Rac1 activation was assayed by the GST-PAK and Rho A by the sepharose pull-down assay. The results of this experiment are presented in Fig. 7 and indicates that IL-19 pretreatment can reduce PDGF-stimulated activation of Rac1 by an average of 70.0% at 10 min PDGF stimulation (4139.0 ± 399 vs. 1220.8 ± 498 for control and IL-19-treated cells, respectively; P < 0.05). IL-19 inhibition was not significant at 20 post-PDGF stimulation. Figure 8 shows that IL-19 significantly decreased RhoA activation by 68% at 10 min PDGF stimulation (8283.7 ± 777 vs. 2622.3 ± 653 for control and IL-19-treated cells, respectively). IL-19 also significantly decreased RhoA activation by 66% at 20 min post-PDGF stimulation. This suggested that IL-19 inhibited an event proximal to these monomeric GTPases.

Fig. 7.

IL-19 inhibits Rac1 activity. A: representative immunoblot of VSMC serum starved for 48 h, and after 4 h IL-19 pretreatment, stimulated with 40 ng/ml PDGF for the times indicated. PAK-bound Rac1 was identified by Western blot analysis and quantitated by densitometry of the corresponding bands. One-tenth the amount of extract was also blotted with Rac1 antibody to document equal amounts of Rac1 in lysates. Gel shown is representative of three experiments performed on three independently derived VSMC. B: scanning densitometry of three experiments from independently treated VSMC (*P < 0.05 compared with non-IL-19-treated control).

Fig. 8.

IL-19 inhibits RhoA activity. A: representative immunoblot of VSMC serum starved for 48 h, and after 4 h IL-19 pretreatment, stimulated with 40 ng/ml PDGF for the times indicated. Rhoteckin-bound RhoA was identified by Western blot analysis and quantitated by densitometry of the corresponding bands. One-tenth the amount of extract was also blotted with RhoA antibody to document equal amounts of RhoA in lysates. Gel shown is representative of three experiments performed on three independently derived VSMC. B: scanning densitometry of three experiments from independently treated VSMC (*P < 0.05, compared with non-IL-19-treated control).

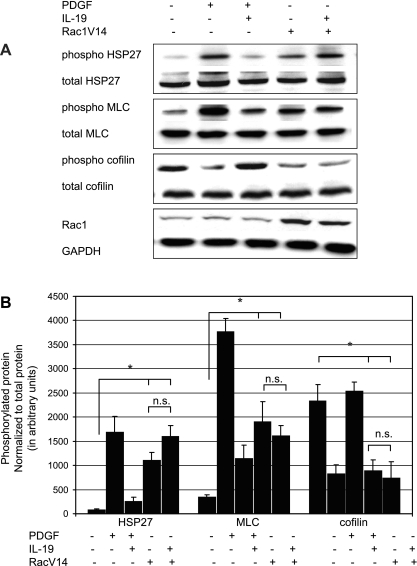

IL-19 inhibitory effects are proximal to Rac1 activity.

IL-19 inhibition of Rac 1 represented a defined constriction point with which to characterize the mechanism(s) of IL-19 inhibitory effects. To ascertain whether IL-19 inhibited events proximal or distal to Rac 1, we transduced VSMC with the constitutively active Rac1V14 mutant (40, 4, 12). VSMC infected with this construct are able to migrate in the absence of chemotactic stimuli (4). VSMC were infected with 30 MOI of AdRacV14 to achieve an approximate fourfold increase in the protein, and after 48 h, migration in the absence of PDGF was assayed by the scratch wound assay. VSMC were incubated 24 h to avoid potential effects of proliferation. As expected, adenoviral-mediated expression of Rac V14 in the absence of PDGF resulted in increased migration of VSMC over unstimulated controls, and IL-19 alone significantly reduced migration. However, Fig. 9 shows that IL-19 does not decrease migration in the scratch wound assay in VSMC that express constitutively active Rac1. In a second series of experiments, we utilized this mutant to determine where in the signaling cascade IL-19 inhibits phosphorylation of cytoskeletal regulatory kinases. VSMC were infected with 30 MOI of AdRacV14, serum starved for 48 h, and then MLC, HSP27, and cofilin activation was examined by Western blot analysis at times found maximal for their activation. Figure 10 shows that RacV14 expression results in constitutively phosphorylated HSP27 and MLC and underphosphorylated cofillin; all indicating activation of these proteins even in the absence of PDGF. Importantly, addition of IL-19 has no inhibitory effect on RacV14 activation of these proteins. Interestingly, IL-19 did tend to decrease Rac1V14-induced phosphorylation of HSP27 but not to a significant degree. Together, both cell functional and molecular assays show that IL-19 inhibitory activity targets a point or points proximal to Rac1 activation.

Fig. 9.

IL-19 inhibitory effects migration are proximal to Rac1 activity. A: migration by Scratch wound. VSMC were infected with 30 MOI of AdRacV14, and after 48 h, migration by the scratch wound assay was performed as described for Fig. 2. Images are representative of at least 3 slides. B: quantitative analysis of scratch wound area from three different groups of treated VSMC. *Significant difference from 3 different slides of IL-19-treated versus untreated control (P < 0.05). IL-19-treated wound was significantly larger than control, and both RacV14 and RacV14 + IL-19-treated wound sizes were significantly smaller than control (P < 0.05). n.s., not significant.

Fig. 10.

IL-19 inhibitory effects on activation of cytoskeletal regulatory proteins are proximal to Rac1 activity. A: representative immunoblots of VSMC infected with 30 MOI of AdRacV14. After 48 h serum starvation, VSMC were pretreated for 4 h with IL-19 and then stimulated 30 min with PDGF. Lysates were examined for phosphorylation state of indicated phosphoproteins as previously described. Gels shown are representative of three experiments performed on three independently derived VSMC. B: quantitative scanning densitometry of three experiments from independently treated VSMC. In all cases the RacV14 and RacV14 + IL-19-treated samples were significantly different from unstimulated controls (*P < 0.05 compared with non-IL-19-treated control), and the RacV14 and RacV14 + IL-19 samples were not significantly different from each other.

DISCUSSION

This is the first study to report that IL-19 has inhibitory effects on VSMC motility and activation of cytoskeletal and migratory regulatory proteins. Various pro-inflammatory interleukins such has IL-1, IL-8, IL-17, and IL-20 have been identified to increase SMC migration and matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) production (30, 29, 33), but very little is known about the effects of anti-inflammatory Th2 interleukins on VSMC migration. Because migration is such an important part of multiple vascular diseases, we hypothesized that IL-19 would attenuate VSMC migration. Four-hour pretreatment with IL-19 significantly reduces PDGF-induced increase in VSMC migration by 30%. Scrape wounding of cell monolayers is a useful model for elucidating the mechanisms of cell migration. As primary VSMC display contact inhibition, unidirectional migration is limited to those cells adjacent to the wound and is polarized into the wound space. IL-19 also decreases this unidirectional migration of VSMC into the scrape wound compared with untreated controls. IL-19 is a ligand for the IL-20 receptor, and antibody directed to this receptor negates the inhibitory effect of IL-19. In both of these assays, the VSMC needs to change its shape to orientate into the direction of migration. Lamellipodia extrusion and cytoplasmic streaming at the cell periphery is necessary to drive cell locomotion, reflected by an increase in cell surface area. IL-19 can significantly reduce surface area of VSMC by 43%. This is the first to report that IL-19 can reduce cell size and migration, in any cell type.

Very little has been reported regarding anti-inflammatory cytokine reduction of SMC migration. A single report indicates that the archetypal anti-inflammatory interleukin IL-10 can inhibit VSMC migration where it was hypothesized that this inhibition was mediated by an nuclear factor (NF)-κB-dependent mechanism (20). In contrast to IL-10, we have previously reported that IL-19 does not inhibit NF-κB activity (5), which prompted us to look elsewhere for potential mechanisms of these inhibitory effects. Cytoskeletal reorganization is requisite for leading-edge cellular protrusion during locomotion, and VSMC migration requires a rearrangement in the VSMC cytoskeleton (13, 14, 23). This, together with our observed decrease in cell surface area, prompted us to examine IL-19 effects on proteins that regulate VSMC cytoskeleton and migration.

Phosphorylation of MLC by myosin light chain kinase (MLCK) is an essential biochemical event in SMC migration as it initiates myosin ATPase activity, polymerization of actin cables, and organization of a functional actin-myosin motor unit necessary for directional cell movement (17, 23, 1). Many chemotactic cytokines initiate migration by activation of MLCK and phosphorylation of MLC (14, 16). MLCK-specific inhibitors block VSMC migration, and MLC phosphorylation is required for MAPK-induced cell migration (16, 18). However, nothing has been reported regarding inhibition of MLC phosphorylation by anti-inflammatory interleukins. In the present study, pretreatment of VSMC with IL-19 results in significant reduction in MLC phosphorylation, and this is the first report of reduction of PDGF-driven MLC phosphorylation by IL-19 or any other anti-inflammatory cytokine. Potential explanations for this reduction may lie in IL-19 effects on kinases proximal to MLCK. MAPK p44/42 (ERK1 and ERK2) promote cell motility and also activate MLCK leading to MLC phosphorylation, and we have previously reported that IL-19 decreases p44/42 activation (36). In addition, MLCK is proximal to Rac1, which is also inhibited by IL-19 (Fig. 7).

The important role of cofilin and other actin remodeling proteins in VSMC migration has been well established (13). Cofilin exists in a phosphorylated state in unstimulated VSMC. Cofilin is activated by PDGF, and its activity is regulated by dephosphorylation, which allows it to bind to F-actin at the leading lamellipodia of the migrating cell (11). In the present study, pretreatment of hVSMC with IL-19 significantly reduced cofilin dephosphorylation, providing a potential mechanism for IL-19 anti-migratory effects. Cofilin activity can be modulated by HSP27, which is a chaperone protein abundant in SMC (15). HSP27 is phosphorylated in response to PDGF stimulation, and phosphorylation of HSP27 is necessary for PDGF-driven SMC migration (15). Phosphorylation-negative mutants of HSP27 inhibit cell migration, and over expression of phosphorylated HSP27 increases SMC migration (2). In this study, pretreatment of VSMC with IL-19 results in significant inhibition of HSP27 phosphorylation, which may explain why dephosphorylation of cofilin is also reduced by IL-19. HSP27 can be phosphorylated by MAP kinases, and a p38/HSP27 pathway has been proposed as important for regulation of SMC migration in response to pro-inflammatory cytokines (15). The p38 kinase cascade has been implicated in regulation of SMC migration in a number of reports (14, 36). This is relevant in that we have previously reported that IL-19 pretreatment can significantly reduce p38 activation in response to FCS stimulation, though we did not examine migration in that report (36).

It is generally accepted that the numerous and varied cytoskeletal alterations needed for cell motility require the active participation small GTPases including RhoA and Rac1 (14, 12). Each of these monomeric GTPases are implicated in vascular disorders such as remodeling, regulation of blood pressure, and wound healing (23). Activation by receptor tyrosine kinases, particularly the PDGF receptor, places Rac1 and RhoA activation as early events in signaling pathways that initiate VSMC migration (23, 6). Importantly, activation of Rac1 is necessary for PDGF-driven VSMC migration, and a dominant negative Rac1 (N17) inhibits migration (4, 5). The present study shows that pretreatment of VSMC with IL-19 significantly reduces activation of Rac1, which is noteworthy in that at least one indirect downstream effector of Rac1 is cofilin (35). Expression of constitutively active RacV12 increases basal invasion of cells, even in the absence of PDGF, suggesting that Rac1 activation is sufficient to induce migration independent of an external stimulus (4). We took advantage of this and expressed this mutant to determine whether IL-19 inhibitory effects were proximal or distal to Rac 1. In our system, adenoviral-mediated expression of Rac V14 resulted in increased migration of VSMC, as well as constitutive activation of cofilin, MLC, and HSP27 in the absence of PDGF. Neither migration nor activation of these proteins were attenuated by addition of IL-19, indicating that inhibitory effects are either directly on Rac1 or proximal to Rac1 activation. In some SMC, Rac1 is an upstream mediator of p38 (27, 38). Thus IL-19 effects on p38 or proximal mediators of p38 activation may account for the inhibitory effect of IL-19 and regulators of VSMC motility.

Calcium signaling plays an important role in VSMC migration but was not thoroughly investigated in this study because of the kinetics of IL-19 pretreatment necessary for inhibitory effects. In SMC, calcium rises within minutes in response to PDGF treatment, but 4 h of IL-19 pretreatment was necessary for inhibitory effects. Simultaneous addition of IL-19 and PDGF had no inhibition of activation of regulatory protein phosphorylation. Additionally, one of the earliest events in IL-19 signaling is rapid activation of STAT3 (8, 36), and there is little literature linking STAT3 activation with inhibition of calcium signaling. Many pro-migratory signals such as PDGF initiate both calcium-dependent and calcium-independent pathways, thus inhibition of calcium flux may not necessarily influence phosphorylation of distal proteins (10). Nevertheless, none of these reasons completely eliminates the possibility that IL-19 can reduce calcium signaling, and this limitation does require further study. One interesting consideration in all of these experiments is that 4 h of IL-19 pretreatment appeared to be optimal for inhibition of cytoskeletal regulatory proteins. This implies that de novo synthesis, or de novo activation, of a protein or proteins are necessary for IL-19 inhibitory effects. Furthermore, since 8 and 16 h of preincubation were not as effective at inhibition of these signaling events, this also implies that this factor, or the activity of this factor, is short-lived and transient. Further experimentation is necessary to determine whether IL-19 does induce expression of an inhibitory factor or factors.

In summary, there are at least four novel points to this study: 1) IL-19 decreases VSMC migration and chemotaxis; 2) IL-19 decreases VSMC size; 3) IL-19 decreases activation of cytoskeletal regulatory proteins including HSP27, cofilin, and MLC; and 4) IL-19 decreases activity of the small GTPase Rac1, an important regulator of cell motility. IL-19 inhibitory target is likely proximal to this factor. These findings are novel for the effects of Th2 interleukins on VSMC, in general, and IL-19 in particular.

This is innovative in that it links an anti-inflammatory mediator with beneficial cellular effects on VSMC and suggests that IL-19 may represent a novel therapeutic modality for many vascular diseases.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant HL-090885 and American Heart Association Grant 0455562U to M. V. Autieri.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Dr. Satoru Eguchi for critical evaluation of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1. Adelstein RS. Regulation of contractile proteins by phosphorylation. J Clin Invest 72: 1863–1866, 1983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. An SS, Fabry B, Mellema M, Bursac P, Gerthoffer WT, Kayyali US, Gaestel M, Shore SA, Fredberg JJ. Role of heat shock protein 27 in cytoskeletal remodeling of the airway smooth muscle cell. J Appl Physiol 96: 1701–1713, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Autieri MV, Kelemen SE, Wendt KW. AIF-1 is an actin-polymerizing and Rac1-activating protein that promotes vascular smooth muscle cell migration. Circ Res 92: 1107–1114, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Banyard J, Anand-Apte B, Symons M, Zetter BR. Motility and invasion are differentially modulated by Rho family GTPases. Oncogene 19: 580–91, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cuneo AA, Herrick D, Autieri MV. IL-19 Reduces VSMC activation by regulation of mRNA regulatory factor HuR and reduction of mRNA stability. J Mol Cell Cardiol 49: 647–654, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Doanes AM, Irani K, Goldschmidt-Clermont PJ, Finkel T. A Requirement for Rac1 in the PDGF-stimulated migration of fibroblasts and vascular smooth cells. Biochem Mol Biol Int 45: 279–287, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Englesbe MJ, Deou J, Bourns BD, Clowes AW, Daum G. Interleukin-1beta inhibits PDGF-BB-induced migration by cooperating with PDGF-BB to induce cyclooxygenase-2 expression in baboon aortic smooth muscle cells. Vasc Surg 39: 1091–1096, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gallagher G, Dickensheets H, Eskdale J, Izotova LS, Mirochnitchenko OV, Peat JD, Vazquez N, Pestka S, Donnelly RP, Kotenko SV. Cloning, expression and initial characterization of interleukin-19 (IL-19), a novel homologue of human interleukin-10 (IL-10). Genes Immun 1: 442–450, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gallagher G, Eskdale E, Jordan W, Peat J, Campbell J, Boniotto M, Lennon GP, Dickensheets H, Donnelly RP. Human interleukin-19 and its receptor: a potential role in the induction of Th2 responses. Int Immunopharmacol 4: 615–626, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gerthoffer WT. Mechanisms of vascular smooth muscle cell migration. Circ Res 100: 607–21, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ghosh M, Song X, Mouneimne G, Sidani M, Lawrence DS, Condeelis JS. Cofilin promotes actin polymerization and defines the direction of cell motility. Science 304: 743–746, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gregg D, Rauscher FM, Goldschmidt-Clermont P. Rac regulates cardiovascular superoxide through diverse molecular interactions: more than a binary GTP switch. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 285: C723–C734, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gunst SJ, Zhang W. Actin cytoskeletal dynamics in smooth muscle: a new paradigm for the regulation of smooth muscle contraction. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 295: C576–C587, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hall A. Small GTP-binding proteins and the regulation of the actin cytoskeleton. Annu Rev Cell Biol 10: 31–54, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hedges JC, Dechert MA, Yamboliev IA, Martin JL, Hickey E, Weber LA, Gerthoffer WT. A role for p38(MAPK)/HSP27 pathway in smooth muscle cell migration. J Biol Chem 274: 24211–24219, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jay PY, Pham PA, Wong SA, Elson EL. A mechanical function of myosin II in cell motility. J Cell Sci 108: 387–393, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kishi H, Bao J, Kohama K. Inhibitory effects of ML-9, wortmannin, and Y-27632 on the chemotaxis of vascular smooth muscle cells in response to platelet-derived growth factor-BB. J Biochem 128: 719–22, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Klemke RL, Cai S, Giannini AL, Gallagher PJ, de Lanerolle P, Cheresh DA. Regulation of cell motility by mitogen-activated protein kinase. J Cell Biol 137: 481–492, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Libby P. Inflammation in atherosclerosis. Nature 420: 868–874, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mazighi M, Pellé A, Gonzalez W, Mtairag el M, Philippe M, Hénin D, Michel JB, Feldman LJ. IL-10 inhibits vascular smooth muscle cell activation in vitro and in vivo. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 287: H866–H871, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Moore KA, Sethi R, Doanes M, Johnson TM, Pracyk JB, Kirby M, Irani K, Goldschmidt-Clermont PJ, Finkel T. Rac1 is required for cell proliferation and G2/M progression. Biochem J 326: 17–20, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nakayama M, Amano M, Katsumi A, Kaneko T, Kawabata S, Takefuji M, Kaibuchi K. Rho-kinase and myosin II activities are required for cell type and environment specific migration. Genes Cells 10: 107–17, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. van Nieuw Amerongen GP, van Hinsbergh VWM. Cytoskeletal effects of Rho-like small guanine nucleotide-binding proteins in the vascular system. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 21: 300–311, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Oral H, Kotenko S, Yilmaz M, Mani O, Zumkehr J, Blaser K, Akdis C, Akdis M. Regulation of T cells and cytokines by the interleukin-10 (IL-10)-family cytokines IL-19, IL-20, IL-22, IL-24 and IL-26. Eur J Immunol 36: 380–388, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Parrish-Novak J, Xu W, Brender T, Yao L, Jones C, West J, Brandt C, Jelinek L, Madden K, McKernan PA, Foster DC, Jaspers S, Chandrasekher YA. Interleukins 19, 20, and 24 signal through two distinct receptor complexes. Differences in receptor-ligand interactions mediate unique biological function. J Biol Chem 277: 47517–47523, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Pestka S, Krause CD, Sarkar D, Walter MR, Shi Y, Fisher PB. Interleukin-10 and related cytokines and receptors. Ann Rev Immunol 22: 929–979, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Pichon S, Bryckaert M, Berrou E. Control of actin dynamics by p38 MAP kinase–Hsp27 distribution in the lamellipodium of smooth muscle cells. J Cell Sci 117: 2569–77, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Piotrowicz RS, Martin JL, Dillman WH, Levin EG. The 27-kDa heat shock protein facilitates basic fibroblast growth factor release from endothelial cells. J Biol Chem 272: 7042–7047, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Raines E, Ferri N. Cytokines affecting endothelial and smooth muscle cells in vascular disease. J Lipid Res 46: 1081–1092, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ross R. The pathogenesis of atherosclerosis: a perspective for the 1990s. Nature 362: 801–809, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rousseau S, Houle F, Landry J, Huot J. p38 MAP kinase activation by vascular endothelial growth factor mediates actin reorganization and cell migration in human endothelial cells. Oncogene 15: 2169–2177, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. San Martín A, Lee MY, Williams HC, Mizuno K, Lassègue B, Griendling KK. Dual regulation of cofilin activity by LIM kinase and Slingshot-1L phosphatase controls platelet-derived growth factor-induced migration of human aortic smooth muscle cells. Circ Res 102: 432–438, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Singer C, Sonemany S, Baker K, Gerthoffer W. Synthesis of immune modulators by smooth muscles. Bioessays 26: 646–655, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sommerville LJ, Xing C, Kelemen SE, Eguchi S, Autieri MV. Inhibition of allograft inflammatory factor-1 expression reduces development of neointimal hyperplasia and p38 kinase activity. Cardiovasc Res 81: 206–215, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Stowers L, Chant J. GTPase cascades choreographing cellular behavior: movement, morphogenesis, and more. Cell 81: 1–4, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Tian Y, Sommerville LJ, Cuneo A, Kelemen SE, Autieri MV. Expression and suppressive effects of interleukin-19 on vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation, signaling, and development of intimal hyperplasia. Am J Pathol 173: 901–909, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Weber DS, Taniyama Y, Rocic P, Seshiah PN, Dechert MA, Gerthoffer WT, et al. Phosphoinositide-dependent kinase 1 and p21-activated protein kinase mediate reactive oxygen species-dependent regulation of platelet-derived growth factor-induced smooth muscle cell migration. Circ Res 94: 1219–1226, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Welt FGP, Rogers C. Inflammation and restenosis in the stent era. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 22: 1769–1776, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wu Y, Rizzo V, Liu Y, Sainz IM, Schmuckler NG, Colman RW. Kininostatin associates with membrane rafts and inhibits vβ3 integrin activation in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 27: 1968–1975, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Yamamoto H, Atsuchi N, Tanaka H, Ogawa W, Abe M, Takeshita A, Ueno H. Separate roles for H-Ras and Rac in signaling by transforming growth factor (TGF)-beta. H-Ras is essential for activation of MAP kinase, partially required for transcriptional activation by TGF-beta, but not required for signaling of growth suppression by TGF-beta. Eur J Biochem 264: 110–119, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]