On May 18th 2009, I left work and set off to collect my children from school in Muscat, Oman’s capital city. Seat belt securely fastened, I was alone in my new car, a Tucson Hyundai. The next thing I knew was floating in and out of consciousness three days later in a Hospital Intensive Care Unit, gradually realising I had been the victim of a serious road traffic accident.

Apparently, one car had overtaken another on the main Sultan Qaboos Highway causing the driver to lose control, collide with a central lamp post and fly over the very low divide, hitting me on the other side of the highway. My car then hit a fourth car. The driver of a car behind, on a visit to me in the ICU, later described the car that hit me as, “Flying over like a rocket or a bolt of light.” He saw smoke rising from my car engine. Fearing an explosion, he decided to move me before the ambulance arrived and with the help of two other men, lifted me out of the back of my car. He found my phone and called someone who knew my husband’s number. An ambulance quickly arrived and took the man from the car that hit me to a nearby hospital; he died nine days later, apparently just a week before his planned wedding day. A second ambulance arrived fifteen minutes later and took me to the same hospital and then to one with orthopaedic expertise.

My family arrived in A&E, where, according to my records, I was “fully conscious and oriented,” although to this day I remember nothing. The staff took X-rays, began stabilizing me and wheeled me into the ICU. Swollen, bruised and broken, I had 17 fractures (to my skull, thorax, pelvis, upper and lower limbs), a collapsed lung and severe polytrauma.

The first days passed in a complete blur. Then I became vaguely aware of visitors popping in, nurses turning me every few hours, which was agony, tubes sticking out of my body and non-stop noise in the ward. A team of general ICU surgeons came daily to treat my chest injuries and prepare me for surgery. The CT scans were a huge ordeal, making me feel like I was falling completely out of control. Being shifted off the bed onto a stretcher and into the scanner caused enormous pain, so I prayed hard for help to be able to cope. The medicine I received brought on hallucinations: embarrassing and frustrating experiences. I was vaguely aware of other patients, some needing frantic attention, some not making it. I didn’t eat or drink much, which obviously would have helped my recovery.

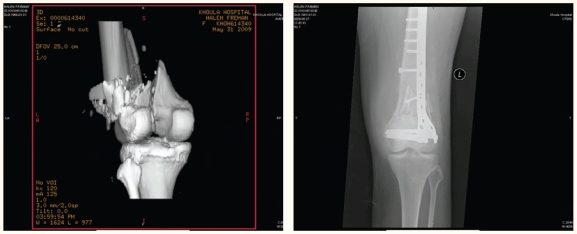

My first operation took place 10 days after being admitted to hospital. I just remember that I wanted to get on with it and become more comfortable. I had retrograde nailing of the right femur fracture, which had broken into three pieces, a partial patellectomy and fixation of five pieces with cerclage wires. The team of orthopaedic surgeons also plated my left radius and ulna, taking 8 hours. Five days later, the second operation, lasting nearly 6 hours, consisted of plating of my left femur with bone grafting. This had been badly smashed into over 50 pieces and was a difficult repair job. I remember being wheeled into the theatre, feeling like a slab of meat being laid onto a cold table with doctors and their knives gathering round ready to carve me up. Both operations went well, although the second lung collapsed around this time. A scaphoid cast was applied to my right wrist, so I now had plaster on all four limbs. A hole was drilled through my right heel bone and a pin fitted from which 4 kgs of weight were suspended as a way of treating the acetabular fracture in my pelvis with skeletal traction. Although doctors told me this was standard procedure, it seemed like medieval torture and remained severely uncomfortable until it was eventually removed. My nasal bone, base of skull, clavicle, and ribs healed without intervention.

Three weeks after the accident and a week after my second operation, I was discharged from the ICU to the women’s orthopaedic ward. Still on a lot of medication I was plagued by hallucinations, vomiting and diarrhoea. There was no one to one patient to nurse ratio in this ward and most patients had an attendant, often a sister or mother, staying with them. I therefore struggled to get the attention I needed. Family and friends came to look after me and could see that my condition was bad. I felt their concern and worry, which in turn upset me. My hair, which had been washed on a daily basis in the ICU, became badly knotted. A nurse gave me what ranks as my worst ever hair cut! At the time, I hardly noticed. After three days, the senior doctor was called up from ICU to see me. She immediately decided to rush me back into ICU suspecting septicaemia, lung and urine infections. This time the ICU doctors thought I would not make it. They put me in an isolation room and onto a ventilator and other vital organ monitors, with round the clock nursing care. Three days passed without my knowing it, and then I spent the rest of that week slowly recovering. I really hated having nasal tubes and needles stuck into various parts of my body. It was such a relief to have them removed. The ICU nurses and doctors showed great compassion, efficiency and kindness and we really appreciated their care. Personal touches comforted me: one doctor came bearing coffee and sat with me.

Moved back to the women’s ward, this time in a better condition, I started to eat again and interact with others. Many people visited - wafts of incense, chatting, laughing and sharing fruit, the flimsy curtains separating beds allowing little privacy. I found sleeping difficult due to chanting, neighbours snoring, cell phones, crying, TV blaring, nurses talking and early morning bed baths.

I began to realise my condition more and felt aghast at the sight of my swollen knees. I was able to cry about the enormity of my situation for the first time. Gradually nurses removed tubes, bandages and stitches and physiotherapists introduced gentle exercises for my totally atrophied muscles. It took four physiotherapists to lift me into a wheelchair and after half an hour of wheeling around the corridors with a friend in attendance, I would be exhausted. I also used a passive exercise machine for my very stiff left leg, but with only one in the hospital, it was not often available. I found this rather surprising in an orthopaedic hospital and a country where so many people suffer as a result of road traffic accidents. One mother commented: “In some countries they have guns and bombs, here we have car crashes.”

My husband managed to get me a private room in the hospital, but there I had no physiotherapist visits and 5 days later was shifted back to the women’s ward in floods of tears with a multi-drug resistant hospital infection feeling this was a huge step backwards. I just wanted to go home. My small windowless isolation room confined me like a leper for a further nine days. On 4 July, 48 days after admission, I returned home in an ambulance as I couldn’t yet manage a wheelchair. I remember seeing the tops of buildings go past and feeling sorry that I wasn’t driving, then quickly realising that I could have left hospital in a coffin. That turned my griping into gratitude.

A health carer we had employed in hospital helped me for the next two months on the long journey of recuperation. I also had regular and intensive high quality home-based physiotherapy, which really helped me gain perspective and make progress. My unstable condition, as well as recommendations about the quality of ICU care and orthopaedic surgery in Oman, had encouraged us to remain rather than seek the treatment abroad offered by my employers. Visitors during the summer cheered me up and helped my recovery.

Throughout this whole process, I needed 11 units of blood. During one operation the surgeons requested 4 units, but only 3 were available. This prompted a friend and my husband to instigate a blood donation drive. People donated 100 units of blood and others were turned away, as staff in the mobile unit couldn’t cope. I felt happy to hear of such a positive response to my horrible accident.

Since July, 2 months after my accident, I have progressed from the wheelchair to standing and walking, initially in the swimming pool and then with a Zimmer frame, crutches and a walking stick. Now, 7 months later, I walk without aid. We, as a family, have celebrated every small step as a great achievement: bed sores healing, extracting a stray stitch from a scar and my first shower. Relief flooded in as I became able to do things myself.

One day my left arm became hot, red and swollen. We rushed to hospital dreading being readmitted. The X-rays indicated a loose screw in the ulna fixation. The doctor allayed our fears saying that I had probably just bumped my arm. My consultant surgeon wondered whether I would need manipulation under anaesthetic or open quadricepsplasty of my left knee, but decided to see how much aggressive physiotherapy could improve knee and hip movement first. Exercise is crucial and I spend time on a bike, in the pool and with steps and weights. The limited movement in my stiff left knee is likely permanent and I may later require a total hip replacement.

I thank all the doctors, nurses, physiotherapist, orthopaedic osteopath, chiropractor, my employers, friends, all those who prayed for my recovery and especially my family for their amazing support.

Figures 1a & 1b.

Left Femur/Knee before and after the operation