Abstract

Various assessment methods are available to assess clinical competence according to the model proposed by Miller. The choice of assessment method will depend on the purpose of its use: whether it is for summative purposes (promotion and certification), formative purposes (diagnosis, feedback and improvement) or both. Different characteristics of assessment tools are identified: validity, reliability, educational impact, feasibility and cost. Whatever the purpose, one assessment method will not assess all domains of competency, as each has its advantages and disadvantages; therefore a variety of assessment methods is required so that the shortcomings of one can be overcome by the advantages of another.

Keywords: Medical Education, Undergraduate, Assessment, Educational

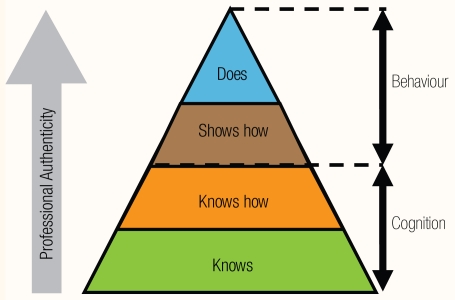

In 1990, Miller proposed a hierarchical model for the assessment of clinical competence.1 This model starts with the assessment of cognition and ends with the assessment of behaviour in practice [Figure 1]. Professional authenticity increases as we move up the hierarchy and as assessment tasks resemble real practice. The assessment of cognition deals with knowledge and its application (knows, knows how) and this could span the levels of Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives from the level of comprehension to the level of evaluation.2 The assessment of behaviour deals with assessment of competence under controlled conditions (shows how) and the assessment of competence in practice or the assessment of performance (does). Different assessment tools are available which are appropriate for the different levels of the hierarchy. Van der Vleuten proposed a conceptual model for defining the utility of an assessment tool.3 This is derived by conceptually multiplying several weighted criteria on which assessment tools can be judged. These criteria were validity (does it measure what it is supposed to be measuring?); reliability (does it consistently measure what it is supposed to be measuring?); educational impact (what are the effects on teaching and learning?); acceptability (is it acceptable to staff, students and other stakeholders?), and cost. The weighting of the criteria depended on the purpose for which the tool was used. For summative purposes, such as selection, promotion or certification, more weight was given to reliability while for formative purposes, such as diagnosis, feedback and improvement, more weight was given to educational impact.4 Whatever the purpose of the assessment it is unlikely that one method will assess all domains of competency. A variety of assessment methods are, therefore, required. Since each assessment method has its own advantages and disadvantages, by employing a variety of assessment methods the shortcomings of one can be overcome by the advantages of another.

Figure 1.

Miller’s hierarchical model for the assessment of clinical competence1

This paper will not be an exhaustive review of all assessment methods reported in the literature, but only those with clear conclusions about their validity and reliability in the context of undergraduate medical education although many of them are also used in postgraduate medical education also. Some new trends, although still requiring further validation, will also be considered.

Assessment of Knowledge and its Application

The most common method for the assessment of knowledge is the written method (which can also be delivered online). Several written assessment formats are available to choose from. It should be noted, however, that in choosing any format, the question that is asked is more important than the format in which it is to be answered. In other words, it is the content of the question that determines what the question tests.5 For example, sometimes, it is incorrectly assumed that multiple choice questions (MCQ) are unsuitable for testing problem solving ability because they require students to merely recognise the correct answer, while in open ended questions they have to generate the answer spontaneously. Multiple choice questions can test problem solving ability if constructed properly.5,6,7 This does not exclude the fact that certain question formats are more suitable than others for asking certain types questions. For example, when an explanation is required, an essay question will, obviously, be more suitable than an MCQ.

Every question format has its own advantages and disadvantages which must be carefully weighed when a particular question type is chosen. It is not possible that one type of question will serve the purpose of testing all the aspects of a topic. Therefore, a variety of formats are needed to counter the possible bias associated with individual formats and they should be consistent with the stated objectives of the course or programme.

MULTIPLE CHOICE QUESTIONS (A-TYPE: ONE BEST ANSWER)

These are the most commonly used question type. They require examinees to select the single best response from 3 or more options. They are relatively easy to construct and enjoy high reliability per hour of testing since they can be used to sample a broad content domain. MCQs are often misconstrued as tests of simple facts, but, if constructed well, they can test the application of knowledge and problem solving skills. If questions are context-free, they almost exclusively test factual knowledge and the thought process involved is simple.6 Contextualising the questions by including clinical or laboratory scenarios not only conveys authenticity and validity, but, also, is more likely to focus on important information rather than trivia. The thought process involved is also more complex with candidates weighing different units of information against each other when making a decision.6 Examples of well constructed one best answer questions and guidelines about writing such questions can be found in Case and Swanson.7

MULTIPLE CHOICE QUESTIONS (R-TYPE: EXTENDED MATCHING ITEMS)

One approach to context-rich questions is extended matching questions or extended matching items (EMQs or EMIs).8 EMIs are organised into sets of short clinical vignettes or scenarios that use one list of options that are aimed at one aspect (e.g. all diagnoses, all laboratory investigations, etc). These options can range from 5 to 26 (although 8 options have been advocated to make more efficient use of testing time).9 Some options may apply to more than one vignette while others may not apply at all. A well-constructed extended matching set includes four components: theme, options list, lead-in statement, and at least two item stems. An example and guidelines for writing such questions are shown in Case and Swanson.7

KEY FEATURES QUESTIONS

Key features questions are short clinical cases or scenarios which are followed by questions aimed at key features or essential decisions of the case.10 These questions can either be multiple choice or open ended questions. More than one correct answer can be provided. Key feature questions have been advocated to test clinical decision-making skills with demonstrated validity and reliability when constructed according to certain guidelines.11 Although these questions are used in some “high-stakes” examinations in places such as Canada and Australia,11 they are less well known than the other types and their construction is time consuming, especially if teachers are inexperienced question writers.12

SHORT ANSWER QUESTIONS (SAQS)

These are open-ended questions that require students to generate an answer of no more than one or two words, rather than to select from a fixed number of options. Since they require some time to answer, not many SAQs can be asked in an hour of testing time. This leads to less reliable tests because of limited sampling. Also, their requirement to be marked by a content expert makes them more costly and time consuming; therefore, they should only be used when closed formats are excluded. It is important that the questions are phrased unambiguously and a well defined answer key is written before marking the question.13 If multiple examiners are available, double marking is preferred. For efficiency, however, each marker should correct the same question for all candidates. This leads to more reliable scores than if each marker corrects all the questions of one group of candidates while another marker corrects all questions for another group.5

ESSAY QUESTIONS

Essay questions are used when candidates are required to process, summarise, evaluate, supply or apply information to new situations. They require much more time to answer than short answer or multiple choice questions and, therefore, not quite as many questions can be used per hour of testing; hence, their lower reliability. Structuring (but not overstructuring) the marking process and using a correction scheme similar to the one used for short answer questions can improve reliability. The guidelines for writing short answer questions apply also to essay questions.13

MODIFIED ESSAY QUESTIONS (MEQS)

This is a special type of essay question that consists of a case followed by a series of questions that relate to the case and that must be answered in the sequence asked. This leads to question interdependency and a student answering the first question incorrectly is likely to answer the subsequent questions incorrectly too. Therefore, no review or possibility of correcting previous answers is allowed and the case is reformulated as the reporting process progresses. A well-written MEQ assesses the approach of students to solving a problem, their reasoning skills, and their understanding of concepts, rather than recall of factual knowledge.14 Due to psychometric problems associated with question interdependency, MEQs are being replaced by the key feature questions.13 An example of an MEQ can be found in Knox.14

SCRIPT CONCORDANCE TEST (SCT)

A new format that is slowly gaining acceptance in health professions education is the script concordance test (SCT). This format is designed to test clinical reasoning in uncertain situations15 and is, as the author puts it, based on “the principle that the multiple judgments made in these clinical reasoning processes can be probed and their concordance with those of a panel of reference experts can be measured.”16 The test has gained face validity since its content resembles the tasks that clinicians do every day. SCTs are based on short case scenarios followed by related questions that are presented in three parts: the first part (“if you were thinking of”) contains a relevant diagnostic or management option; the second part (“and then you were to find”) presents a new clinical finding, and the third part (“this option would become”) is a fivepoint Likert scale that captures examinees’ decisions as to what effect the new finding has on the status of the option. An example of an SCT question and guidelines for their construction can be found in Demeester and Charlin.17

Assessment of Performance

Assessment of performance can be divided into two categories; assessment of performance in vitro, i.e. in simulated or standardised conditions, and assessment of performance in vivo, i.e. in real conditions. Both categories involve demonstration of a skill or behaviour continuously or at a fixed point in time by a student and observation and marking of that demonstration by the examiner. Several tools such as checklists, rating scales, structured and unstructured reports can be used to record observations and to assist in the marking or assessment of such demonstrations. Checklists and rating scales are used as scoring methods in various forms of assessments, including Objective Structured Clinical or Practical Examinations (OSCE, OSPE), Direct Observation of Procedural Skills (DOPS), peer assessment, self assessment, and patient surveys.18

The assessment of actual performance, i.e. what the doctor does in practice, is the ultimate goal for a valid assessment of clinical competence. However, despite the face validity of this “in-training” assessment, problems of inadequate reliability due to lack of standardisation, limited observations and limited sampling of skills are cause of concern and limits their use as summative “high-stakes” or qualifying examinations. To mimic real conditions, assessments in simulated settings have been designed to assess performance such as OSCE/ OSPE.

CHECKLISTS

Checklists are useful for assessing any competence or competency component that can be broken down into specific behaviours or actions that can be either done or not done. It is recommended that over-detailed checklists should be avoided as they trivialise the task and threaten validity.4 Global ratings (a rating scale which is used in a single encounter, for example in an OSCE, in addition to or instead of a checklist, to provide an overall or “global” rating of performance across a number of tasks) provide a better reflection of expertise than detailed checklists.19

Checklist development requires consensus by several experts on the essential behaviours, actions, and criteria for evaluating performance. This is important to ensure validity of content and scoring rules. Also, in order to obtain consistent scores and satisfactory reliability, evaluators who are trained in the use of checklists should be used. An example of a checklist can be found in Marks and Humphrey-Murto.20

RATING SCALES

Rating scales are widely used to assess behaviour or performance. They are particularly useful for assessing personal and professional attributes, generic competencies and attitudes. The essential feature of a rating scale is that the observer is required to make a judgement along a scale that may be continuous or intermittent. An unavoidable problem of rating scales is the subjectivity and low reliability of the judgements. To be fair to the student, however, multiple independent ratings of the same student undertaking the same activity are necessary. It is also important to train the observers to use the rating forms. Guidelines on improving the quality of rating scales can be found in Davis and Ponnamperuma.21

OBJECTIVE STRUCTURED CLINICAL EXAMINATION (OSCE)

The OSCE is primarily used to assess basic clinical skills.22 Students are assessed at a number of “stations” on discrete focused activities that simulate different aspects of clinical competence. At each station standardised patients (SPs), real patients or simulators may be used,23 and demonstration of specific skills can be observed and measured. OSCE stations may also incorporate the assessment of interpretation, non-patient skills and technical skills. Each student is exposed to the same stations and assessment. OSCE stations may be short or long (5–30 minutes) depending on the complexity of the task. The number of stations may vary from as few as eight to more than 20 although an OSCE with 14–18 stations is recommended to obtain a reliable measure of performance.18 Reliability is a function of sampling and, therefore, of the number of stations and competences tested.24 Scoring is done with a task specific checklist or a combination of a checklist and a rating scale. Global ratings produce equivalent results as compared to checklists.19,25,26 The scoring of the students or trainees may be done by observers (faculty members, patients, or standardised patients).

Tips on organising OSCE examinations can be found in Marks and Humphrey-Murto.20

SHORT CASES

Short cases assessment is commonly used in several places27,28 to assess clinical competence.29 In this type of assessment, students are asked to perform a supervised focused physical examination of a real patient, and are then assessed on the examination technique, the ability to elicit physical signs and interpret these findings correctly. Several cases are used in any one assessment to increase the sample size. Studies on the validity and reliability of short case assessment, however, are scarce and, as Epstein30 advocates, their empirical validation must be done before promoting their use.

LONG CASES

The long case has traditionally been used to assess clinical competence. In the long case, students interview and examine a real patient and then summarise their findings to one or two examiners who question the students by an unstructured oral examination on the patient problem and other relevant topics. The student’s interaction with the patient is usually unobserved. The long case has face validity and authenticity since the task undertaken resembles what the doctor does in real practice; however, the use of long case assessment in “high-stakes” summative examinations is not recommended,31 and, in fact, it has been discontinued in North America, due to its low reliability.32 On the other hand, its use in formative examinations is encouraged because of its perceived educational impact.33 To increase the validity and reliability of long cases, several modifications have been introduced, for example: observing the candidates while they interact with the patient34,35 (although observing the candidate is not a major contributor to reliability);36 training the examiners to a structured examination process,37 and increasing the number of cases.36,38

360° evaluation

360° evaluation is a multi-source feedback assessment system that evaluates an individual’s competence from multiple perspectives within their sphere of influence. Feedback is objectively and systematically collected via a survey or rating scale that assesses how frequently a behaviour is performed. Multiple evaluators, who may include superiors, peers, students, administrative staff, patients and families, rate trainee performance in addition to the trainee doing a self-assessment. The rating scales vary with the assessment context.

360° evaluations have been used to assess a range of competencies, including professional behaviours, at undergraduate39 and postgraduate levels.40 However, the use of 360° evaluations in summative assessment is not advocated until further studies are conducted to establish their reliability and validity.40 Their use in formative evaluations might be more appropriate since evaluators provide more balanced and honest feedback when the evaluation is formative and used for developmental purposes rather than for pass/fail decisions.41 Nonetheless, it should be borne in mind that this type of evaluation can be time consuming and administratively demanding.42 An example of a 360° evaluation form used in a study can be found in Wood et al.43

MINI CLINICAL EVALUATION EXERCISES (MINI-CEX)

Mini-CEX44 are based on tutor observations of routine interactions that supervising clinicians and trainees have on a daily basis. These trainee-patient encounters occur on multiple occasions with different evaluators and in different settings. They are relatively short observations (15–20 minutes) in which performance is recorded on a 4 point scale where 1 is unacceptable, 2 is below expectation, 3 is met expectations, and 4 is exceeded expectations. There is an opportunity for noting that a particular behaviour was unobserved and additional space to record details about the context of the encounter. The mini-CEX incorporates an opportunity for feedback from the evaluator and is mostly used for formative assessment.39 Evaluators consist mostly of tutors whose primary role is to teach clerkship students.39

Several competencies are evaluated by the mini-CEX: history taking, physical examination, clinical judgement, counselling, professionalism and other generic qualities. An example of a mini-CEX tool can be found in Norcini.44

PORTFOLIOS

A portfolio is a collection of student work which provides evidence that learning has taken place. It includes documentation of learning and progression, but most importantly a reflection on these learning experiences.45

Portfolios documentation may include case reports; record of practical procedures undertaken; videotapes of consultations; project reports; samples of performance evaluations; learning plans, and written reflection about the evidence provided. Scoring methods include checklists and rating scales developed for a specific learning and assessment context and are usually carried out by several examiners who probe students regarding portfolio contents and decide whether the student has reached the required standard.45

Portfolio assessment is considered a valid way of assessing outcomes; however, it has low to moderate reliability due to the wide variability in the way portfolios are structured and assessed. Also, this form of assessment is not considered very practical due to the time and effort involved in its compilation and evaluation46 and, perhaps for these reasons, portfolios are commonly used for formative assessment and less commonly for summative purposes.47,48 However, at present, the strength and extent of the evidence base for the educational effects of portfolios in the undergraduate setting is limited.49 Guidelines for portfolio compilation can be found in Friedman et al.,46 Snadden and Thomas,50 and Thistlethwaite.51

Conclusion

Various assessment methods that test a range of competencies are available for examiners. The choice should be dictated by fitness for purpose and a number of utility criteria. The importance and weighting of these criteria depends on the purpose of the assessment method, i.e. either summative, formative or both.

References

- 1.Miller GE. The assessment of clinical skills/ competence/performance. Acad Med. 1990;65:S63–7. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199009000-00045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bloom BS. Handbook I: Cognitive domain. New York: David McKay; 1956. Taxonomy of educational objectives. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Van der Vleuten CPM. The assessment of professional competence: developments, research and practical implications. Adv Health Sci Educ. 1996;1:41–67. doi: 10.1007/BF00596229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van der Vleuten CP, Schuwirth LW. Assessing professional competence: from methods to programmes. Med Educ. 2005;39:309–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2005.02094.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schuwirth LW, van der Vleuten CP. Different written assessment methods: what can be said about their strengths and weaknesses? Med Educ. 2004;38:974–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2004.01916.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schuwirth LW, Verheggen MM, van der Vleuten CP, Boshuizen HP, Dinant GJ. Do short cases elicit different thinking processes than factual knowledge questions do? Med Educ. 2001;35:348–56. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2001.00771.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Case SM, Swanson DB. Constructing written test questions for the basic and clinical sciences. [Accessed April 2010]. From http://www.nbme.org/PDF/ItemWriting_2003/2003IWGwhole.pdf.

- 8.Case SM, Swanson DB. Extended-matching items: a practical alternative to free response questions. Teach Learn Med. 1993;5:107–15. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Swanson DB, Holtzman KZ, Allbee K. Measurement characteristics of Content-Parallel Single-Best-Answer and Extended-Matching Questions in relation to number and source of options. Acad Med. 2008;83:S21–4. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318183e5bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bordage G, Page G. In: An alternate approach to PMPs, the key feature concept. Further developments in assessing clinical competence. Hart I, Harden R, editors. Montreal: Can-Heal Publications; 1987. pp. 57–75. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Farmer E, Page G. A practical guide to assessing clinical decision-making skills using the key features approach. Med Educ. 2005;39:1188–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2005.02339.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schuwirth LWT, van der Vleuten CP. ABC of learning and teaching in medicine: Written assessment. BMJ. 2003;326:643–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7390.643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schuwirth LWT, van der Vleuten CP. In: Written Assessments. Dent J, Harden R, editors. New York: Elsevier Churchill Livingstone; 2005. pp. 311–22. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Knox JD. How to use modified essay questions. Med Teach. 1980;2:20–4. doi: 10.3109/01421598009072166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Charlin B, van der Vleuten CP. Standardized assessment of reasoning in context of uncertainty. The Script Concordance Test approach. Eval Health Profess. 2004;27:304–19. doi: 10.1177/0163278704267043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hall KH. Reviewing intuitive decision-making and uncertainty: the implications for medical education. Med Educ. 2002;36:216–24. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2002.01140.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fournier JP, Demeester A, Charlin B. Script Concordance Tests: Guidelines for Construction. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2008;8:18. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-8-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.ACGME Outcome Project, Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) and American Board of Medical Specialist (ABMS) Toolbox of assessment methods. Sep, 2000. [Accessed May 2010]. Version 1.1 From http://www.acgme.org/outcome/assess/toolbox.asp.

- 19.Regehr G, MacRae H, Reznick R, Szalay D. Comparing the psychometric properties of checklists and global rating scales for assessing performance on an OSCE format examination. Acad Med. 1998;73:993–7. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199809000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marks M, Humphrey-Murto S. In: Performance Assessment. Dent J, Harden R, editors. New York: Elsevier Churchill Livingstone; 2005. pp. 323–35. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davis MH, Ponnamperuma GG. In: Work-based Assessment. Dent J, Harden R, editors. New York: Elsevier Churchill Livingstone; 2005. pp. 336–45. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harden RM, Gleeson FA. ASME Medical Education Booklet No. 8: Assessment of clinical competence using an objective structured clinical examination (OSCE) Med Educ. 1979;13:41–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Collins JP, Harden RM. AMEE Education Guide No. 13: The use of real patients, simulated patients and simulators in clinical examinations. Med Teach. 1998;20:508–21. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Newble D, Swanson D. Pschycometric characteristics of the objective structured clinical test. Med Educ. 1988;22:325–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.1988.tb00761.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Govaerts M, van der Vleuten CP, Schuwirth LM. Optimising the reproducibility of a performance-based test in midwifery. Adv Health Sci Educ. 2002;7:133–45. doi: 10.1023/a:1015720302925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Swartz M, Colliver J, Bardes C, Charon R, Fried E, Moroff S. Global ratings of videotaped performance versus global ratings of actions recorded on checklists: a criterion for performance assessment with standardized patients. Acad Med. 1999;74:1028–32. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199909000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fowell SL, Maudsley G, Maguire P, Leinster SJ, Bligh J. Student assessment in undergraduate medical education in the United Kingdom, 1998. Med Educ. 2000;34:S1–49. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2000.0340s1001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hijazi Z, Premadasa IG, Moussa MA. Performance of students in the final examination in paediatrics: importance of the “short cases.”. Arch Dis Child. 2002;86:57–8. doi: 10.1136/adc.86.1.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wass V, van der Vleuten C, Shatzer J, Jones R. Assessment of clinical competence. Lancet. 2001;357:945–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04221-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Epstein RM. Assessment in medical education. Author’s reply. New Eng J Med. 2007;356:2108–10. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra054784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ponnamperuma GG, Karunathilake IM, McAleer S, Davis MH. The long case and its modifications: a literature review. Med Educ. 2009;43:936–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03448.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smee S. Skill based assessment. BMJ. 2003;326:703–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7391.703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wass V, van der Vleuten C. The long case. Med Educ. 2004;38:1176–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2004.01985.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wass V, Jolly B. Does observation add to the validity of the long case? Med Educ. 2001;35:729–34. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2001.01012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Newble DI. The observed long case in clinical assessment. Med Educ. 1991;25:369–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.1991.tb00083.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wilkinson TJ, Campbell PJ, Judd SJ. Reliability of the long case. Med Educ. 2008;42:887–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2008.03129.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Olson LG, Coughlan J, Rolfe I, Hensley MJ. The effect of a structured question grid on the validity and perceived fairness of a medical long case assessment. Med Educ. 2000;34:46–52. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2000.00465.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hamdy H, Prasad K, Williams R, Salih FA. Reliability and validity of the direct observation clinical encounter examination (DOCEE) Med Educ. 2003;37:205–12. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2003.01438.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rees C, Shepherd M. The acceptability of 360-degree judgements as a method of assessing undergraduate medical students’ personal and professional behaviours. Med Educ. 2005;39:49–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2004.02032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Office of Postgraduate Medical Education. Review of work-based assessment methods. Sydney: University of Sydney, NSW, Australia; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Higgins RS, Bridges J, Burke JM, O’Donnell MA, Cohen NM, Wilkes SB. Implementing the ACGME general competencies in a cardiothoracic surgery residency program using 360-degree feedback. Annals Thoracic Surg. 2004;77:12–17. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2003.09.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Joshi R, Ling FW, Jaeger J. Assessment of a 360-degree instrument to evaluate residents’ competency in interpersonal and communication skills. Acad Med. 2004;79:458–63. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200405000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wood J, Collins J, Burnside ES, Albanese MA, Propeck PA, Kelcz F, et al. Patient, faculty, and self-assessment of radiology resident performance: a 360-egree method of measuring professionalism and interpersonal/ communication skills. Acad Radiol. 2004;11:931–9. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2004.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Norcini JJ, Blank LL, Duffy FD, Fortna GS. The mini-CEX: a method for assessing clinical skills. Annals Internal Med. 2003;138:476–83. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-6-200303180-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Davis MH, Ponnamperuma GG. In: Portfolios, projects and dissertations. Dent J, Harden R, editors. New York: Elsevier Churchill Livingstone; 2005. pp. 346–56. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Friedman MB, David MH, Harden RM, Howie PW, Ker J, Pippard MJ. AMEE guide No. 24: Portfolios as a method of student assessment. Med Teach. 2001;23:535–51. doi: 10.1080/01421590120090952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rees C, Sheard C. The reliability of assessment criteria for undergraduate medical students’ communication skills portfolios: The Nottingham experience. Med Educ. 2004;38:138–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2004.01744.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Davis M, Friedman B, Harden R, Howie P, McGhee C, Pippard M, et al. Portfolio assessment in medical students’ final examinations. Med Teach. 2001;23:357–66. doi: 10.1080/01421590120063349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Buckley S, Coleman J, Davison I, Khan KS, Zamora J, Malick S, et al. The educational effects of portfolios on undergraduate student learning: a Best Evidence Medical Education (BEME) systematic review. BEME Guide No. 11. Med Teach. 2009;31:279–81. doi: 10.1080/01421590902889897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Snadden D, Thomas M. The use of portfolio learning in medical education. Med Teach. 1998;20:192–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.1998.00245.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Thistlethwaite J. How to keep a portfolio. Clin Teach. 2006;3:118–23. [Google Scholar]