Abstract

The ‘Learning Organisation’ is a concept first described by Peter Senge as an organisation where people continuously learn and enhance their capabilities to create. It consists of five main disciplines: team learning, shared vision, mental models, personal mastery and systems thinking. These disciplines are dynamic and interact with each other. System thinking is the cornerstone of a true learning organisation and is described as the discipline used to implement the disciplines. In a learning organisation, health care education aims to educate its members with up to date knowledge to produce competent and safe personnel, who can promote quality in health care services. In addition, there are some educational concepts and theoretical models, which are of relevance to the learning organisation, and can provide a framework for managerial decisions. The stages required to achieve the principles of a learning organisation will be described in detail. Moreover, in a proper culture which supports the learning organisation, members continuously learn to improve the environment and never remain passive recipients.

Keywords: Learning organisation, Healthcare education, Leadership

The ‘Learning Organisation’ is a concept that is becoming an increasingly widespread philosophy in modern health care institutions. What is achieved by this philosophy depends considerably on one’s interpretation of it and commitment to it. Much has been written about the concept of a learning organisation1,2 and some attempts, such as those by Critten, and other writers 3 have been made to translate the concept into practice. According to Peter Senge, learning organisations are:

…organisations where people continually expand their capacity to create the results they truly desire, where new and expansive patterns of thinking are nurtured, where collective aspiration is set free, and where people are continually learning to see the whole together.4

So, the concept of the learning organisation is that any successful organisation must continually learn in order to adapt to changes in the environment and grow.

Any organisation that wants to implement a learning organisation philosophy requires an overall strategy with clear, well defined goals. Once these have been established, the tools needed to facilitate the strategy must be identified.

The building blocks of a learning organisation are, initially, individuals and then teams, who create, share and act on collective learning. Such an organisation operates an organisational learning cycle where new knowledge is created, captured, shared and implemented.5, 6 In a learning organisation, managers - supported by human resources department professionals - have a key role in creating opportunities for individuals and/or teams to learn and sharing learning in work.7, 8

THE LEARNING ORGANISATION

CHARACTERISTICS OF SUCCESSFUL TEAMS

An organisation development plan is the process through which an organisation develops the internal capacity to be optimally effective in its work and to sustain itself over the long term. Organisation development interventions are divided into two basic groups: diagnosis and action or process. Team building is one type of process intervention. Team work is considered as the fundamental unit and the building block of the learning organisation.

Teams and team work have been studied by many writers looking for the characteristics that make for success. Larson and LaFasto looked at high performance groups as diverse as a championship football team and a heart transplant team and found eight characteristics that are always present.9 They are listed below:

A clear, elevating goal

A results-driven structure

Competent team members

Unified commitment

A collaborative climate

Standards of excellence

External support and recognition

Principled leadership

TEAM FORMATION

Before a team can learn, it has to be formed. In the 1970s, psychologist B. W. Tuckman identified four stages that teams had to go through to be successful. They are:

Forming: When a group is just learning to deal with one another; a time when minimal work gets accomplished.

Storming: A time of stressful negotiation of the terms under which the team will work together; a trial by fire.

Norming: A time in which roles are accepted, team feeling develops and information is freely shared.

Performing: When optimal levels are finally reached in productivity, quality, decision making, allocation of resources, and interpersonal interdependence.9

FIVE DISCIPLINES CRUCIAL TO A LEARNING ORGANISATION

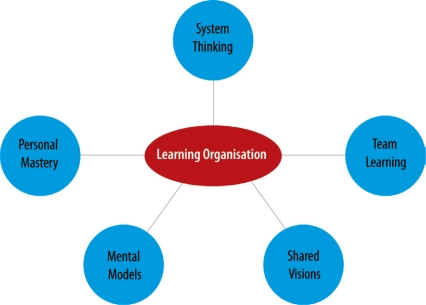

There are five disciplines which are crucial to a learning organisation and should be encouraged at all times.4,10 These are as follows, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1:

The five disciplines of a learning organisation

Team Learning

Teams, not individuals, are the fundamental learning units and unless a team can learn the organisation cannot learn. Consequently, team learning focuses on the learning ability of the group. Mature people learn best from each other by reflecting on how they are addressing problems, questioning assumptions and receiving feedback from their team and from their results. Through team learning, the learning ability of the group becomes greater than the learning ability of any individual in the group.

The discipline of team learning starts with ‘dialogue’, the capacity of members of a team to suspend assumptions and enter into a genuine ‘thinking together’. To the Greeks dialogos meant a free-flowing of meaning through a group, allowing the group to discover insights not attainable individually. It also involves learning how to recognize the patterns of interaction in teams that undermine learning.4

Shared Visions

In order to generate a shared vision, large numbers of people within the organisation must draft it, thus empowering them to create a single image of the future. To become reality all members of the organisation must understand, share and contribute to the vision. People will then do things out of personal commitment, not because of external pressure.

Mental Models

These are deeply ingrained assumptions, generalisations, or even pictures and images, that influence how we understand the world and how we take action.4

Every human being has an internal image of the world, with deep-rooted assumptions. Therefore, individuals will behave according to the true mental model that they subconsciously hold and usually not according to the theories in which they claim to believe. If group members can constructively challenge each others’ ideas and assumptions, they can begin to recognise their mental models and to change these to construct a shared mental model for the team. This is essential as the individual’s mental model will control what they think can or cannot be done.

Personal Mastery

Personal mastery is one of the core disciplines for building a learning organisation. It refers to an individual commitment to life-long learning; it is a continuous and never-ending process.4

Personal mastery can be defined as the process of continually clarifying and deepening an individual’s personal vision. This is a matter of personal choice for the individual and involves persistently assessing in an objective manner the gap between their current and desired proficiencies, and practising and refining skills until they are internalised. This would develop self-esteem and creates the confidence to deal with new challenges.

Personal mastery has three important elements: commitment to truth, personal vision and creative tension. Personal mastery allows individuals to look at their current reality and desired future (commitment to truth and reality), continually focus and clarify their personal vision for the desired future (personal vision) and use these gaps to create the dynamic energy to get to their desired future (creative tension).

Systems Thinking

The foundation of any learning organisation is the fifth discipline - systems thinking. This is the ability to see the bigger picture, to look at the interrelationships of a system as opposed to simple cause-effect chains thus allowing continuous processes to be studied rather than single snapshots. Also, this discipline shows us that the essential properties of a system are not determined by the sum of its parts, but by the process of interactions between those parts. This is why systems thinking is fundamental to any learning organisation as it is the discipline used to implement the disciplines. Without it, each of the disciplines would be isolated and consequently not achieve their objective. Systems thinking enables the formation of an integrated system, whose properties exceed the sum of its parts. Nevertheless, all of the other four disciplines mentioned above are required to successfully implement systems thinking.

System thinking is the mainstay of a true learning organisation, integrating the above disciplines and is a way of discovering solutions to complex problems. This discipline enables interrelationships between systems and teams; at the same time, it allows the organization, through linear and logical thinking, to understand the source of and the solutions to modern problems.

In summary, the five factors identified are dynamic in the way they interact with each other. For instance, when people are given genuine freedom and are trusted to handle their jobs through adequate support from other team members and appropriate resources, innovation and diversity of ideas will increase.11 This will cultivate a sense of the bigger picture and increase their capacity to know and act upon the events.

THE LEARNING ORGANISATION AND HEALTH CARE EDUCATION

The aim of professional health care education is to educate health care personnel with up to date knowledge and skills, either by theoretical learning through attending courses or practical through training programmes. The core purpose of health care education is to promote quality in health care service by having competent and safe personals.

TRAINING AND LEARNING ISSUES

Training can help shape ideas and aspirations, because it involves learning new things. Depending on the type of training, it can be the most effective way of learning. The difference between training and learning is that individuals are different when it comes to learning. This can lead to a number of unpredictable outcomes, such as increased motivation and self-confidence, changing attitudes and insights which shape future actions.12, 13

EDUCATIONAL CONCEPTS AND THEORETICAL MODELS

The use of the term theory in education does not need to imply something remote from the day to day experience of the teacher. It is suggested that there is no real dichotomy between theory and practice. Also, to some extent, theory serves to provide a rationale for decision-making. Managerial activity is enhanced by an explicit awareness of the theoretical framework underpinning practice in educational institutions.14 Theory is useful as long as it has relevance to practice in education. Theodossin clarifies that academics tends to want understanding for knowledge, while managers seek understanding for action.15 In discussing the relevance of educational concepts to the learning organisation the following should be taken into account:16, 17

Awareness

Organisations must be aware that learning is necessary and must take place at all levels, not just the management level. Once the educational institution has accepted the need for change, it is then responsible for creating the appropriate environment in order for this change to occur.

Environment

Centralised, mechanistic structures do not create a good environment as individuals do not have a comprehensive picture of the whole organisation and its goals. This causes political and parochial systems to be set up which stifle the learning process. Therefore a more flexible and a flatter structure, which encourages innovations, would be more suitable. The flatter structure also promotes the passing of information between workers, so creating a more informed work force.

It is necessary for management to embrace a new philosophy: to encourage openness, reflectivity and accept error and uncertainty. Staff members need to be able to question decisions without the fear of reprimand. This questioning can often highlight problems at an early stage and reduce time consuming errors. One way of overcoming this fear is to introduce anonymity so that questions can be asked or suggestions made, but the source is not necessarily known.

Leadership

In a learning organisation, leaders are designers, stewards and teachers. They are responsible for building organisations.4 Leaders should promote the systems thinking concept and encourage learning to help both the individual and the organisation in learning. It is the leader’s responsibility to help change the individual views of team members. For example, they need to help the teams understand that competition is a form of learning, not a hostile act.

Management must provide commitment for long-term learning in the form of resources. The amount of resources available (money, personnel and time) determines the quantity and quality of learning. This means that the organisation must be prepared to support this. Leaders have to generate and manage creative tension – especially around the gap between vision and reality. Mastery of such tension allows for a fundamental shift. It enables the leader to see the truth in changing situations.

Empowerment (flatter hierarchies)

Empowerment has been variously defined, but its core idea is based on creating an environment where others are equipped and encouraged to make decisions in autonomous ways and to feel that they are in control of the outcomes for which they have accepted responsibility. The locus of control shifts from managers to workers (‘empowerment’) thus making workers responsible for their actions, but the managers do not lose their involvement. They still need to encourage, enthuse and co-ordinate the workers.

Empowerment can help organisations tackle the uncertainties of today’s changing world by drawing out the creative potential of the people who make up the organisation.

Learning from mistakes

Staff members need to find out what failure is like so that they can learn from their mistakes in the future. The managers are then responsible for setting up an open, flexible atmosphere in their organisations to encourage their workers to follow their learning example. Anonymity can be achieved through electronic conferencing; this type of conferencing can also encourage different sites to communicate and share knowledge.

Finally, the fifth discipline (systems thinking) has close theoretical linkages with single-loop (adaptive) and double-loop (generative) learning.18 Adaptive learning routines can help health care professionals to follow pre-set pathways, detect and correct errors. This is also referred to as single-loop learning, an example being the clinical audit. Single-loop learning is the method of learning where you find a better way to do a process and it is comparable to the idea of continuous quality improvement. Double-loop learning goes a step further and asks, ‘why are we doing the process in the first place?’ The self-generating behaviour resulting from adaptive learning is determined by the operating norms or standards that guide it. Developing evidence-based practitioners may be one way to facilitate double-loop learning.19

The learning-loop concept takes into account the cognitive and behavioural aspects of human development; together they form the theoretical foundation of the organisational learning framework.20 At the centre of these approaches is the importance of promoting creative individualism within organisations, so as to make people feel empowered. Consequently, employees will be challenged to find better ways of meeting organisational goals and values.21, 22

HEALTH CARE PROFESSIONALS’ FORMS OF KNOWLEDGE AND HEALTH CARE QUALITY

Organisational learning and knowledge management are two concepts that have developed in parallel and are often linked in their definitions and practice.23 Organisational learning is referred to as changes in the state of knowledge and involves knowledge acquisition, dissemination, refinement, creation and implementation: the ability to acquire diverse information and to share common understanding so that this knowledge can be exploited.24, 25 Organisational knowledge is stored partly in individuals in the form of experience, skills and personal capability, and partly in organisations, in the form of documents, records, rules, regulations and standards, etc.26 Therefore, the main task for the management is to create a learning environment between individuals and the organisation in order to facilitate the interaction and strengthening of each other’s knowledge.27 Thus, organisational learning is collective learning.

Health care professionals are obligated both to acquire and maintain the expertise needed to undertake their professional tasks. Additionally, they are also obligated to undertake only those tasks that are within their competence and to acquire technical knowledge in their field of work.

Other forms of knowledge (list adapted from Nutley and Davies,19) which can be gained by health care professionals (HCP) from their learning organisation are:

-

1.

Formal knowledge, such as structured programmes and written procedures. This can be gained through attending courses, conferences and workshops.

-

2.

Informal knowledge, such as that learned from different informal situations. Also, people learn skills and acquire knowledge beyond their specific job requirements. This enables them to appreciate or perform other roles and tasks.

-

3.

Tacit knowledge arising from the capabilities of people, particularly the skills that they have developed over time.

-

4.

Cultural knowledge relating to the customs, values and relationships with clients and other stakeholders. These are: celebration of success, absence of complacency, tolerance of mistakes, recognition of tacit knowledge, mutual trust, belief in human potential and staff empowerment. By being aware of their role and importance in the whole organisation, the workers are more motivated to ‘add their bit’. This encourages creativity and free-thinking, hence leading to novel solutions to problems. All in all, there is an increase in job satisfaction and health care quality standards.

Other important issues related to knowledge and high quality service are:

-

5.

Flexibility at work allows workers to move freely within departments and enables them to choose their own speciality, whilst at the same time it removes the barriers associated with rigidly structured training programmes and promotes creativity.

-

6.

Knowledge and accountability. Denyes et al.28 state that scientific accountability is a characteristic of a profession. Knowledge, skill and attitude are considered the most basic pre-requisites for accountability. Responsibility must be given or taken to carry out an action and then authority is legitimised power, i.e. the legal right to carry out the responsibility.29 An example of this is the implementation of a staff appraisal system.

-

7.

Knowledge and empowerment Equal participation must be allowed at all levels so that members can learn from each other simultaneously.

In the UK, the government ensures that the national quality standards are applied consistently within local practice or units through a system of clinical governance. The key characteristics of clinical governance are the importance and interaction of extended life-long learning and modernised professional self-regulation.30, 31, 32 The combination of all three working well will serve good clinical practice and deliver the requirements of the General Medical Council for good medical practice.33 First, clinical governance is a process by which each part of the UK National Health Service (NHS) quality-assures its clinical decisions, backed by a new statutory duty of quality. Second, lifelong learning allows NHS staff to identify the training needs across professions to aid clinical team working. Third, professional self-regulation provides clinicians with the opportunity to help set standards.

The concept has some parallels with the more widely known corporate governance, in that it addresses those structures, systems and processes that assure quality, accountability and proper management of an organisation’s operation and delivery of service. However, clinical governance applies only to health and social care organisations, and only to those aspects of such organisations that relate to the delivery of care to patients and their carers; it is not concerned with the other business processes of the organisation, except in so far as they affect the delivery of care. The concept of ‘integrated governance’ has emerged to refer jointly to the corporate governance and clinical governance duties of healthcare organisations.34

CREATING A CULTURE THAT SUPPORTS THE LEARNING ORGANISATION

Learning organisations embrace change and constantly create the reference points to precipitate an ever-evolving structure that has a vision of the future built in to it. According to Richard Karash, learning organisations are healthier places to work because they:

Garner Independent Thought

Improve Quality

Develop a More Committed Work Force

Increase our Ability to Manage Change

Give People Hope that Things Can Get Better

Stretch Perceived Limits

Are in Touch with a Fundamental Part of our Humanity.35

One of the biggest challenges that must be overcome in any organisation is to identify and breakdown the ways people reason defensively. Everyone must learn that the steps they use to define and solve problems can be a source of additional problems for the organisation.36

HOW TO ACHIEVE THE PRINCIPLES OF A LEARNING ORGANISATION

The first step is to create a timeline to initiate the types of changes that are necessary to achieve the principles of a learning organisation; these changes are described in details by Gaphart as follows:37

STAGE ONE

To create a communication system to facilitate the exchange of information, which is the basis on which any learning organisation is built. The use of technology has and will continue to alter the workplace by enabling information to flow freely and to “provide universal access to business and strategic information.”

STAGE TWO

To organize a readiness questionnaire, which acts as a tool to assess the distance between where an organisation is and where it would like to be, in terms of the following seven dimensions:

Providing continuous learning

Providing strategic leadership

Promoting inquiry and dialogue

Encouraging collaboration and team learning

Creating embedded structures for capturing and sharing learning

Empowering people toward a shared vision

Making systems connections

The questionnaire is completed by all employees or a sample of them; its results are then analysed to form an assessment profile, used to design the learning organisation initiative.

STAGE THREE

To commit to developing, maintaining and facilitating an atmosphere that garners learning.

STAGE FOUR

With the help of all employees, is to create a vision of the organisation and write a mission statement.

STAGE FIVE

Through training and awareness programmes, is to try to expand employees’ behaviours to develop skills and understanding attitudes needed to reach the goals of the mission statement, including the ability to work well with others, become more verbal, and network with people across all departments within the organisation.38

STAGE SIX

To communicate a change in the company’s culture by integrating human and technical systems.

STAGE SEVEN

To initiate the new practices by emphasizing team learning and contributions because employees will then become more interested in self-regulation and management, and be more prepared to meet the challenges of an ever-changing workplace.

STAGE EIGHT

To allow employees to question key business practices and assumptions.

STAGE NINE

To develop workable expectations for future actions.38

STAGE TEN

To remember that becoming a learning organisation is a long process and that small setbacks should be expected.

CONCLUSION

A learning organisation encourages its members to improve their personal skills and qualities, so that they can learn and develop. They benefit from their own and other people’s experience, whether they are positive or negative. In a learning organisation, there are more opportunities to be creative and this helps ensure that any individual will be able to cope rapidly with a changing environment and move freely within the organisation.

Effective leadership is the foremost requirement for the creation of a learning organisation, which is not based on traditional hierarchy, but based on a mix of different people from all levels of the system leading in different ways.39

Technological development may replace human resources in some other sectors, but not in the health sector. In the health field, there are very few options for equipment to replace humans. This is one of the explanations for the perpetually high demand for skilled health care professionals all over the world. Another factor necessitating the continuous development of health professionals is the nature of their duties. Since they are dealing with sick human beings, poor performance can cost lives.

REFERENCES

- 1.Burgoyne J, Pedler M, Boydell T. Towards the Learning Company: Concepts and Practices. London: McGraw-Hill; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gordon A, Parsons D, Richards D. Employer Strategies and Investors in People. Horsham: Labour Market Intelligence Unit; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Critten P. Investing in People: Towards Corporate Capability. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Senge PM. The Fifth Discipline: the art and practice of the learning organisation. London: Random House; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nonaka I. The knowledge-creating company. Harvard Business Review. 1991;69:96–104. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dixon N. The Organisational Learning Cycle Maidenhead. McGraw-Hill; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garavan T. Strategic human resource development. J Europ Industr Train. 1991;15:17–31. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Watkins KE, Ellinger AD. 1998. Building learning organisation: new roles for managers and human resource developers, Professors’ Forum, IFTDO Conference, Dublin.

- 9.Larson C, Lafasto F. Teamwork: what must go right, what can go wrong. California, Newbury Park: Sage Publications; 1989. p. 98. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Senge P, Cambron-McCabe N, Lucas T, Smith B, Dutton J, Kleiner A. Schools That Learn A Fifth Discipline Field book for Educators, Parents, and Everyone Who Cares About Education. New York: Doubleday; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harung HS, Heaton DP, Alexander CN. Evolution of organisations in the new millenium. Leadership & Organis Develop J. 1999;20:198–207. [Google Scholar]

- 12.DePhillps FA, Berliner WM, Gribbin JJ. Management of Training Programmes. New York: Richard Irwin; 1960. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Antonagopoulou EP. Do individuals change from learning as well as learn from changing?. Proceedings of the 2nd International Organisational Learning Conference; Lancaster, UK. July 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bush T. Theories of Educational Management. 2nd ed. London: Paul Chapman Publishing; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Theodossin E. Management education and management theory. Coombe Lodge Reports. 1982;15:137–148. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dodgson M. Organisational learning: a review of some literature. Organisation Studies. 1993;14:375–394. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mabey C, Salaman G, Storey J. Human Resources Management: A Strategic Introduction. Oxford: Blackwell; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Senge PM. The Fifth Discipline The art and practice of the learning organisation. London: Century Business; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nutley SM, Davies HTO. Developing organisational learning in the NHS. Med Educ. 2001;35:35–42. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2001.00834.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yeo R. From individual to team learning: practical perspectives on the learning organisation. Team Perform Managt J. 2002;8:157–170. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schein EH. Empowerment, coercive persuasion and organisational learning: do they connect? The Learning Organis. 1999;6:163–172. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Robbins SP. Management. 4th ed. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang CL, Ahmed PK. Organisational learning: a critical review. The Learning Organisation. 2003;10:8–17. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lyles M. Learning among joint venture sophisticated firms. Managt Internat Review. 1998;28:85–98. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fiol M. Consensus, diversity, and learning in organisation. The Learning Organisation. 1994;4:149–158. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weick K, Roberts K. Collective mind in organisations. Heedful interrelating of flight decks. Admin Sci Quart. 1993;38:357–381. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alder PS, Goldoftas B, Levine DI. Flexibility versus efficiency? A case study of model changeovers in the Toyota production systems. Organis Sci. 1999;10:43–68. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Denyes MJ, Connor NA, Oakley D, Ferguson S. Integrating nursing theory: practice and research through collaborative research. J Advan Nurs. 1998;14:141–145. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1989.tb00912.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Manley K. Knowledge for nursing practice. In: Jolley A, editor. Nursing: a Knowledge base for practice. London: Edward Arnold; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Headrick LA, Wilcox PM, Batalden PB. Inter-professional working and continuing medical education. BMJ. 1998;316:771–774. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7133.771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Holm HA. Quality issues in continuing medical education. BMJ. 1998:316. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7131.621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.London: BMA; 1998. British Medical Association, Academy of Medical Royal Colleges COPMED, Committee of Undergraduate Deans, London. Making self-regulation work at local level. [Google Scholar]

- 33.General Medical Council. Maintaining Good Medical Practice. London: GMC; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Clinical governance. From: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Clinical_governance. Accessed August 2007.

- 35.Mason MK. New directions: The learning organization. www.moyak.com. Accessed June 2007.

- 36.Argyris C. Teaching smart people how to learn. Harvard Business Review. 1991;69:99–109. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gephart MA, Marsick VJ, Van Buren ME, Spiro MS. Learning organisations come alive. Train & Develop. 1996;50:35–45. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Navran Associates Newsletter. From: http://www.navran.com. Accessed August 2007.

- 39.Senge P. Leading Learning Organization. Training & Develop. 1996;50:36–37. [Google Scholar]