Abstract

The demographic profile of the Asian population is rapidly changing, with a fast increasing ageing population, owing to an increase in longevity and a decreasing birth rate. Moreover, due to improved medical facilities and the increased aged population, Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is fast emerging as a major health problem in many Asian countries. As curative treatment for AD is still elusive, care giving is an important component of the management of AD. While Western countries have recognised this issue, besides highly industrialized Japan, the Asian initiative has been relatively slow. This article aims to address issues involved in caregiving in AD in some Asian countries.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, ageing population, caregivers

The demographic profile in many Asian countries is in the process of a major shift due to an increasing ageing population that has been arbitrarily defined as one where seven percent of the people are aged over 60 years [Table 1]. The aged population in Asia was conservatively estimated at 8.2 % in 1995 1 and has been predicted to increase to about 10% by year 2010.1 A similar distribution has also been noted in the Eastern Mediterranean region 2 that also includes the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) [Table 2]. While the percentage increase over these years is not very remarkable, in absolute numbers it translates to an enormous increase in aged population and related health care issues. The increase in the aged population has been attributed to an overall improvement in lifestyle standards and consequent longevity.3

Table 1:

Total population over 60 years of age in selected Asian countries (based on Ref: 1)

| Country | 1991 | 2001 |

|---|---|---|

| Bangladesh | 6 million | 11.4 million |

| China | 42 million | 97 million |

| Hong Kong | 772,400 | I million |

| Indonesia | 53 million | 113 million |

Table 2:

Proportion of population 60 years and older for selected countries of the World Health Organization Eastern Mediterranean Region (Based on Ref: 2)

| Country | 60 years and older % |

|---|---|

| Bahrain | 5.2 |

| Iraq | 4.8 |

| Jordan | 3.8 |

| Kuwait | 3.9 |

| Lebanon | 10.4 |

| Oman | 4.5 |

| Palestine | 4.9 |

| Qatar | 6.0 |

| Saudi Arabia | 4.0 |

| Syrian Arab Republic | 4.8 |

ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE

It is paradoxical that improvement in healthcare facilities has resulted in an increased lifespan and a related increase of age-related diseases, significant among which is Alzheimer’s Disease (AD). AD is a chronic neurodegenerative disorder, the most dominant feature of which is cognitive decline. It is characterised by progressive memory loss, personality changes and in its final stages hamper the activities of daily living. The incidence of AD has been directly linked to a high percentage of individuals over 65 years of age, with up to 55% of people over 65 years of age being affected by the disease.3 This has obvious implications for the already over stretched health care system in many Asian counties. It is noteworthy that although females are more represented in caregiving in Asia, their presence does not have a significant impact on the overall caregiving in AD.3

Although AD was identified almost a century ago, a definitive treatment has still eluded mankind. At this juncture, symptomatic palliative treatment along with effective caregiving appears to be the only therapeutic option, with most of the affected persons being cared for at home by informal caregivers, who are usually family members or relatives.4

AD has been identified as the single largest cause of dementia in the Western world5 and its prevalence in some Asian countries is also high [Table 3] and references therein). Thus, as the ageing population continues to grow, society is faced with the dilemma of an increasing prevalence of AD patients and the responsibilities of caring for them. Though the importance of caregiving in AD management has been recognised by many Western countries,6,7 the effort in many Asian counties. the development of caregiver resources has not been significant, except for a few isolated programs.8,9

Table 3:

Prevalence of AD in some Asian countries

In many Asian counties., it is generally believed that caregiving is not just a duty, but also an expression of love and devotion, and there is a great reliance on the family system for support. However, as many Asian caregivers lack adequate medical knowledge, social and emotional skills, the task of care giving becomes even more challenging. This article aims to discuss the issues involved in caregiving in AD in general and specifically in relation to the Asian context.

CAREGIVER ISSUES

Caregiving broadly includes the assistance and monitoring of activities of people affected by disease or disability. Assistance may be in the form of medical, financial, emotional or legal support. On a daily basis, it includes personal care, housekeeping, administration of medication and execution of financial transactions and other responsible activities. Thus, in severely affected persons, such as those with AD, the caregiver becomes an important, albeit essential, factor for their well-being and often existence. In fact, it has been shown that the single predictor of placement of an affected person in a nursing home is the absence of caregivers.10

In the broader context, the important issues involved in the caring of AD patients include:

Recognition of the needs of AD patients

The recognition of the needs and problems of persons affected by AD appears fundamental to caregiving. However, it has been seen that a significant number of caregivers tend to overestimate the physical and mental capabilities of AD patients under their care. They at times fail to realize that even simple directions and instructions maybe be difficult for AD patients to follow due to their dementia. Consequently, failure of their patients to comply with directions often leads to frustration, anger and depression for both the patient and the caregiver.11

Further, dying people have certain rights that broadly include relief from pain, affirmation of the whole person and the right to die with dignity.12 Caregivers need to learn the specific issues in the promotion and protection of these rights in order to provide a positive death experience for a person with AD.

THE CAREGIVER BURDEN

Caregiving is a complex task that is often underplayed. It is physically, mentally and financially stressful for the caregiver, due to complex emotions such as resentment about time and effort expended, sympathy and the anticipated loss of a loved one and often loss of income.13 The resultant changes in lifestyles and goals of a caregiver, often involve a major reorganization of priorities. This results in the loss of free time, neglect of friends and hobbies, often manifesting as social isolation and a consequent decrease in the quality of life of caregivers.13, 14 Analyses have shown that the levels of anxiety and depression in caregivers are directly related to the hours of care required and the physical and psychological illness scores of the AD patients under their care.15

Investigations have been carried out into the reasons for distress of AD caregivers. At the forefront are the low levels of knowledge of caregivers about the prevalence, causes, symptoms and management of AD.16 For example, caregivers often complain of a loss of functional communication with AD patients, who are unable to follow verbal commands. The knowledge that simple sentences, instead of slow speech, while communicating with AD patients is more effective, has been shown to significantly reduce caregiver stress.17 Further, the knowledge of other communication strategies such as direct questioning in contrast to parallel questioning has also been shown to lower the caregiver’s burden.18 Parallel questioning refers to addressing issues in an indirect manner that require a more complicated reply, as compared to direct questioning which usually require a “yes” or “no” response.18

Another significant problem outlined by caregivers is difficulty in finding adequate resources such as effective and convenient medical support and community resources for management of AD patients.19 The importance of this point is emphasized by two studies that have reported that caregivers who attended counselling, where information on care giving in AD was given, had lesser depressive symptoms and anxiety.20,21 However, it is encouraging that in contrast to their counterparts in the Western world, though some Asian caregivers report a general reduction in vitality, many do not experience a decreased level of social functioning.14

BENEFITS OF GOOD CARE GIVING

An efficient system of caregiving in AD is advantageous to all. It is of benefit to affected patients and their caregivers and also the formal health care system. Proper training of caregivers resulted in a general improvement of the physical and psychological health of AD patients, with significantly beneficial effects on their sleeping habits and increased daytime activity.22, 23 Further, training of caregivers that included sessions on good nutritional practices helped in preventing weight loss in AD patients.24 Moreover, affected persons gained significantly from the advantage of being cared for in their familiar surroundings.

Caregivers are particularly vulnerable to physical and mental strain, especially if they are female. Training of caregivers enhances their management ability and enables them to handle disruptive behaviour of their wards and obtain an overall mastery of their situation.21, 22, 24 This training will have to be carried out by health care professionals and will results in less leave of absence from duty and consequently less loss of income. Further, as AD patients decline in their mental state, they become increasingly dependent on their caregivers for important decisions. At this juncture caregivers have an important role in deciding various issues concerning AD patients.

Effective care giving in AD also benefits the formal health care system by reducing the costs of institutionalisation of patients. Current health care practices aim at providing acute care and the convalescent period has shifted from hospitals to the community and home.25 Further, caregivers are able to provide valuable prognostic and therapeutic information to health care professionals regarding the patient’s progress and response to treatment. Moreover, the caregiver is also able to help with memory aids, behavioural interventions, exercise and nutrition and the overall effectiveness of various palliative measures in AD that would otherwise have to be managed by the formal health care system.26

THE ROLE OF DOCTORS AND HEALTH CARE PROFESSIONALS IN THE TRAINING OF CAREGIVERS OF AD PATIENTS

While it is obvious that the training of caregivers has important beneficial effects, a study conducted on 200 clinicians in California, USA showed that though a vast majority of them routinely carried out neurological interventions for patients, only a small number of them actively implemented caregiver support practices.27 An Australian study has also reported that caregivers of AD patients complained of insufficient support from the health care system regarding adequate information about the disease, methods to deal with problem behaviour of their patients and how to access support services from health care agencies.28 While similar studies have not been carried out in Asian countries it can be anticipated that Asian clinicians would demonstrate the same disregard for caregiver support practices.

A study carried out in the UK highlighted three important areas where interventions by doctors or health care professionals can be instrumental in improving caregiving in AD.29 These areas include (i) the caregiver education component, in which the knowledge of the caregiver regarding AD is assessed and the caregiver’s personal model of AD is discussed, (ii) stress management of caregivers, wherein techniques for personal stress management, self monitoring and relaxation are taught and (iii) advice on how to respond to problematic behaviour of AD patients. Hebert et al., 2002, have emphasised that the focus of training of caregivers should be more on methods of coping with the stressful demands of demented patients and task oriented aspects of caregiving, rather than with information on the disease process.30, 31 A more recent report by Greenberger and Litwin 2003, 32 has shown that the most important resources identified by caregivers include a sense of competence and adequate support from professional healthcare providers.31 Further, doctors need to be particularly concerned when the female spouse is the caregiver as a study has shown that as caregivers, wives generally fare worse than husbands due to a possible role reversal.32, 33 This is especially important in the Asian context where men traditionally have more responsible roles than females. While these specific interventions have largely have been described in the European context, they can be modified to suit the Asian context.

Thus, doctors and health care workers need to be aware of the need for adequate training and counselling of caregivers, so they can be effectively incorporated into the treatment plans of AD patients. It is significant to note that, in many cases, most of the physicians find it difficult to explain the diagnosis and treatment to a patient and in such cases the role of caregivers is important regarding the disclosure and treatment of the disease.31–33

CARE GIVING IN ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE: IN MANY ASIAN COUNTIES

With the growing number of aged people and a decreasing household size, many Asian countries are faced with the spectre of an increasing incidence and prevalence of AD and less people to care for the patients.34–39 Care giving in many Asian socieies is at present carried out by family members, with support from family members and friends. It is largely because of tradition inculcated at an early age, that caregiving is perceived as an integral part of life to be carried out with love and sympathy, and as a sign of family and kinship support, though this cultural teaching cannot enhance care for the elderly.40 Moreover, the lack of adequate formal health care support facilities for older people has forced families and other informal caregivers to form the mainstay of support for those affected by AD.41

However, there are certain constraints. One is the need for involvement of caregivers in early detection, diagnosis and treatment of patients who demonstrate early symptoms of AD.42 Further, with the growth of technology, caregivers are using more technology when caring for AD patients. However, adequate skill is lacking in many Asian caregivers.43 Moreover, there is a lack of adequate communication between caregivers and doctors responsible for the management of the patients.44 However, this practice is being forced to undergo transformations, largely due to the pressures of socio-economic changes. The dissolution of extended families because of space constraints and job obligations and an increasing number of women working outside their homes has increased the challenge of caring for older people with AD. Further, effective birth control measures and the resultant reduction in household size and number of siblings to assist parental care has increased the load of caregiving for elders, including those affected by AD4. It is also significant to note that the negligible financial support available to affected people and their caregivers has added to the burden of caregiving in AD, highlighting the importance of monetary resources in the management of AD [Table 4].44

Table 4:

Average household size in some Asian countries (based on Ref: 44)

| Country | 1991 | 2001 |

|---|---|---|

| Bangladesh | 6.7 | 5.5 |

| China | 4.4 | 3.9 |

| Hong Kong | 5.3 | 4.5 |

Thus the changing socioeconomic scenario in Asian countries underscores the need for training of caregivers of AD patients and the development of an effective support system. This is further emphasized by the identification of stress levels being specifically linked to caregiving of AD patients.12–15, 45 It has been shown that relevant information regarding AD was the most important factor in reducing caregiver burden and ensuring effective caregiving for AD patients.46 Further, since caregivers are responsible for many of the decisions regarding AD patients, it strongly suggests the need to provide caregivers with more information in order to promote good decision making.17

Thus, the foremost step in the management of caregiving in AD in many Asian countries is the need for education and an assessment of the perceptions of AD among the lay public and particularly of caregivers of AD patients.47 A study in Hong Kong showed that the vast majority Asian caregivers in many Asian counties. welcomed training workshops for caregivers.41 While this is a laudable approach, it is limited in most Asian countries due to monetary constraints. A more feasible approach, as suggested by Shaji et al., 2003, would be the training of domiciliary outreach services and community-based multipurpose health workers to impart knowledge regarding AD and provide the necessary support to caregivers, which have been highlighted in the previous paragraph, the most salient feature being the identification of the stress levels of caregivers.43 This could be carried out during normal hours as a part of training of the public regarding other health issues. However, it must be emphasised that health workers in developing countries can underreport or overreport services rendered due to inefficient data collection systems or recall bias in the population.47 Thus, appraisal methods for evaluation of caregiver services need to be developed as caregiver support is one of the most important predictors of the well being of an AD patien, and health workers should be utilized for such evaluations. Further, inadequate caregiver support leads to an early discontinuation of home treatment of AD patients and a consequent increase in health management costs when they are institutionalised.

Another useful approach to reducing caregiver burden in AD is by the creation of support groups for caregivers. A study carried out in Hong Kong41 showed that the creation of a mutual support group programme for caregivers of AD had a significant role in improving the quality of life and could be incorporated into health care practices in many Asian countries.48 However, it needs to be noted that that such a support system will be maximally effective only when an adequate care giving system has been developed. Another study has also highlighted that professional contact between caregivers was significant in developing the home skills of caregivers thereby reducing their behavioural symptoms.49, 50

Another significant development that has transcended continental boundaries is the development of internet-based groups that offer caregivers the opportunity to interact with other caregivers for guidance, information and encouragement [Table 5]. The overall development of such resources in the different Asian countries in native languages will significantly improve the quality of life of AD patients and reduce the caregiver’s burden, as caregivers in contact with each other are consistently more knowledgeable. Educating the general public about AD and its care through electronic media would remove much of the social stigma associated with the disease. A significant development in this respect is the development of the Alzheimer’s Caregiver Support Online (http://www.alzonline.net/), a web-based support network for caregivers. A similar online service is offered by the Eastern Michigan University for the health care professionals and caregivers (http://www.emuonline.edu).

Table 4:

Websites related to the information regarding care giving in Alzheimer’s disease.

| Name | Website |

|---|---|

| Alzheimer’s Caregiver Support Online | http://www.alzonline.net |

| The Combined Health Information Database | http://chid.nih.gov |

| Alzheimer’s Disease Education & Referral Centre | http://www.alzheimers.org |

| National Family Caregivers Association | http://www.nfcacares.org |

| Alzheimer’s Association Safe Return | http://www.alz.org/services/safereturn.asp |

| Elder Care Locator | http://www.eldercare.gov |

CONCLUSION

Scientific advances in diagnosis and management of disease has resulted in greater longevity and a consequent increase in the aged population. As definitive treatment for AD is still unavailable, caregiving needs to be recognised as an important component of the management of AD. Caregiving in AD requires a variety of skills that include education about AD, assessment of the physical and mental condition of an AD patient and an effective support system for the caregiver. Disseminating knowledge about the disease, its treatment and the role of caregivers should be the prime aim of AD management.

According to a report, the United Nations estimated that the total number of individuals over 65 years of age, living in the countries of the Eastern Mediterranean Region of the World Health Organization (WHO) is approximately 3.5%, and is expected to approach 3.6% by 2005.47 However, there are differences in the size of the elderly population among the member countries of the GCC, with values ranging from a low 1.1% in Qatar and the United Arab Emirates to a high of 11% in Cyprus.48 A number of factors like reductions in infant and child mortality over several decades, together with a reduction in birth rates, have contributed to a high proportion of elderly people in Cyprus, while a large influx of young immigrant workers has resulted in a low proportion elderly people in the member countries of the GCC.47, 48

It has been noticed that a national policy means a national committee for care of the elderly, usually administered by the Ministry of Social Affairs (or the Ministry of Health in one country and the Directorate of Elderly Care and Gerontology in another).49,50 A decree on social benefits for the elderly exists in one country, while another member country is changing the structure of its national committee to conform to the policy on the elderly adopted by the League of Arab States. Most of these national committees were established between 1996 and 1997, almost immediately after the release in 1995 of the strategy paper on the health care of the elderly by the WHO Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean.51,52, 53

Currently there is no significant support program for patients with AD and also for their caregivers in most Asian countries. The majority of this function is being carried out by non-governmental organizations, which have tried to highlight the role of caregivers in the management of AD patients. Thus, closer collaboration and flexibility is necessary between researchers, clinicians, health care support staff and health policy makers in the different Asian countries to support and strengthen the role of caregivers in AD.

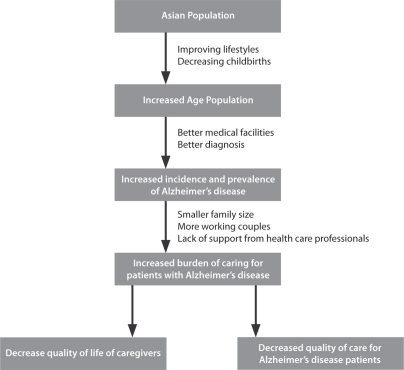

Figure 1:

Effect of changing demographic profile and increased prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease on the Asian population.

REFERENCES

- 1.Achir Y. Indonesian Family Planner warns of 400 million population by 2053. Asia-Pacific POPIN Bulletin. 2003:15. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hafez G, Bagchi K, Mahaini R. Caring for the elderly: a report on the status of care for the elderly in the Eastern Mediterranean Region. East Mediterr Health J. 2000;6:636–643. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lopes MA, Bottino CM. Prevalence of dementia in several regions of the world: analysis of epidemiologic studies from 1994 to 2000. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2002;60:61–69. doi: 10.1590/s0004-282x2002000100012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alzheimer’s Association Statistics/Prevalence (On line) 2001. Available: http://www.alz.org/facts/rstats.htm. Accessed October 13, 2005.

- 5.Foley DJ, Brock DB, Lanska DJ. Trends in dementia mortality from two National Mortality Followback Surveys. Neurology. 2003;60:709–711. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000047131.26946.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Monsch AU, Ermini-Funfschilling D, Mulligan R, et al. Memory Clinics in Switzerland. Collaborative Group of Swiss Memory Clinics. Ann Med Interne. 1998;149:221–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tanner RC. Providers issue brief: family caregiving: year end report-2003. Issue Brief Health Policy Track Serv. 2003:1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Olson P. Caregiving and long-term health care in the People’s Republic of China. J Aging Soc Policy. 1993;5:91–110. doi: 10.1300/J031v05n01_07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Washio M, Arai Y. The new public long-term care insurance system and feeling of burden among caregivers of the frail elderly in rural Japan. Fukuoka Igaku Zasshi. 2001;92:292–298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Finch J, Mason J. Negotiating Family Responsibilities. London: Routledge; 1993. pp. 23–56. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arguelles S, Loewenstein DA, Eisdorfer C, Arguelles T. Caregivers’ judgments of the functional abilities of the Alzheimer’s disease patient: Impact of caregivers’ depression and perceived burden. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2001;14:91–98. doi: 10.1177/089198870101400209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bosek MS, Lowry E, Lindeman DA, Burck JR, Gwyther LP. Promoting a good death for persons with dementia in nursing facilities: family caregivers’ perspectives. JONAS Health Law Ethics Regul. 2003;5:34–41. doi: 10.1097/00128488-200306000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Biegel DE, Sales E, Schultz R. Family Caregiving in Chronic Illness. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 1991. pp. 465–470. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rodriguez G, De Leo C, Girtler N, Vitali P, Grossi E, Nobili F. Psychological and social aspects in management of Alzheimer’s patients: an inquiry among caregivers. Neurol Sci. 2003;24:329–335. doi: 10.1007/s10072-003-0184-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morimoto T, Schreiner AS, Asano H. Caregiver burden and health-related quality of life among Japanese stroke caregivers. Age Ageing. 2003;32:218–223. doi: 10.1093/ageing/32.2.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sansoni J, Vellone E, Piras G. Anxiety and depression in community-dwelling, Italian Alzheimer’s disease caregivers. Int J Nurs Pract. 2004;10:93–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-172X.2003.00461.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Werner P. Correlates of family caregivers’ knowledge about Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;16:32–38. doi: 10.1002/1099-1166(200101)16:1<32::aid-gps268>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Small JA, Gutman G, Makela S, Hillhouse B. Effectiveness of communication strategies used by caregivers of persons with Alzheimer’s disease during activities of daily living. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2003;46:353–367. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2003/028). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roberto KA, Richter JM, Bottenberg DJ, Campbell S. Communication patterns between caregivers and their spouses with Alzheimer’s disease: A case study. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 1998;12:202–208. doi: 10.1016/s0883-9417(98)80025-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Farran CJ, Loukissa D, Perraud S, Paun O. Alzheimer’s disease caregiving information and skills. Part II: family caregiver issues and concerns. Res Nurs Health. 2004;27:40–51. doi: 10.1002/nur.20006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mittelman MS, Roth DL, Coon DW, Haley WE. Sustained benefit of supportive intervention for depressive symptoms in caregivers of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:850–856. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.5.850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Akkerman RL, Ostwald SK. Reducing anxiety in Alzheimer’s disease family caregivers: the effectiveness of a nine-week cognitive-behavioral intervention. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2004;19:117–123. doi: 10.1177/153331750401900202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McCurry SM, Gibbons LE, Logsdon RG, Vitiello M, Teri L. Training caregivers to change the sleep hygiene practices of patients with dementia: the NITE-AD project. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:1455–1460. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51466.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Riviere S, Gillette-Guyonnet S, Voisin T, et al. A nutritional education program could prevent weight loss and slow cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease. J Nutr Health Aging. 2001;5:295–299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gitlin LN, Winter L, Corcoran M, Dennis MP, Schinfeld S, Hauck WW. Effects of the home environmental skill-building program on the caregiver-care recipient dyad: 6-month outcomes from the Philadelphia REACH Initiative. Gerontologist. 2003;43:532–546. doi: 10.1093/geront/43.4.532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Clark M, Steinberg M, Bischoff N. Patient readiness for return home: discord between expectations and reality. Aust Occup Ther J. 1997;44:132–141. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ham RJ. Evolving standards in patient and caregiver support. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 1999;13:27–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rosen CS, Chow HC, Greenbaum MA, Finney JF, Moos RH, Sheikh JI, Yesavage JA. How well are clinicians following dementia practice guidelines? Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2002;16:15–23. doi: 10.1097/00002093-200201000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bruce DG, Paterson A. Barriers to community support for the dementia carer: a qualitative study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2000;15:451–457. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1166(200005)15:5<451::aid-gps143>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marriott A, Donaldson C, Tarrier N, Burns A. Effectiveness of cognitive-behavioural family intervention in reducing the burden of care in carers of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;176:557–562. doi: 10.1192/bjp.176.6.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hebert R, Levesque L, Vezina J, et al. Efficacy of a psychoeducative group program for caregivers of demented persons living at home: a randomized controlled trial. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2003;58:58–67. doi: 10.1093/geronb/58.1.s58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Greenberger H, Litwin H. Can burdened caregivers be effective facilitators of elder care-recipient health care? J Adv Nurs. 2003;41:332–341. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02531.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hooker K, Manoogian-O’Dell M, Monahan DJ, Frazier LD, Shifren K. Does type of disease matter? Gender differences among Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease spouse caregivers. Gerontologist. 2000;40:568–573. doi: 10.1093/geront/40.5.568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chandra V, Pandav R, Dodge HH, et al. Incidence of Alzheimer’s disease in a rural community in India: the IndoUS study. Neurology. 2001;57:985–989. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.6.985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cantegteil-Kallen, Turbelin C, Olaya E, et al. Disclosure of diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease in French general practice. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2005;20:228–232. doi: 10.1177/153331750502000404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.de Silva HA, Gunatilake SB, Smith AD. Prevalence of dementia in a semi-urban population in Sri Lanka: report from a regional survey. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003;18:711–715. doi: 10.1002/gps.909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yan F, Li S, Liu J, Zhang W, Chen C, Liu M, et al. Incidence of senile dementia and depression in elderly population in Xicheng District, Beijing, an epidemiologic study. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2002;82:1025–1028. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Suh GH, Kim JK, Cho MJ. Community study of dementia in the older Korean rural population. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2003;37:606–612. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1614.2003.01237.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ikeda M, Fukuhara R, Shigenobu K, et al. Dementia associated mental and behavioural disturbances in elderly people in the community: findings from the first Nakayama study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75:146–148. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Subgranon R, Lund DA. Maintaining caregiving at home: a culturally sensitive grounded theory of providing care in Thailand. J Transcult Nurs. 2000;11:166–173. doi: 10.1177/104365960001100302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Prince M. 10/66 Dementia Research Group. Care arrangements for people with dementia in developing countries. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004;19:170–177. doi: 10.1002/gps.1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lai CK, Wong FL, Liu KH. A training workshop on late-stage dementia care for family caregivers. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2001;16:361–368. doi: 10.1177/153331750101600607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shaji KS, Smitha K, Lal KP, Prince MJ. Caregivers of people with Alzheimer’s disease: a qualitative study from the Indian 10/66 Dementia Research Network. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003;18:1–6. doi: 10.1002/gps.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Carter RE, Rose DA, Palesch YY, Mintzer JE. Alzheimer’s Disease in the Family Practice Setting: Assessment of a Screening Tool. Prim Care Companion J lin Psychiatry. 2004;6:234–238. doi: 10.4088/pcc.v06n0603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lehoux P. Patients’ perspectives on high-tech home care: a qualitative inquiry into the user-friendliness of four technologies. BMC Health Serv Res. 2004;4:28–36. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-4-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bruce DG, Paley GA, Underwood PJ, Roberts D, Steed D. Communication problems between dementia carers and general practitioners: effect on access to community support services. Med J Aus. 2002;177:186–188. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2002.tb04729.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sullivan K, O’Conor F. Providing education about Alzheimer’s disease. Aging Ment Health. 2001;5:5–13. doi: 10.1080/13607860020020582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nair V, Thankappan K, Sarma P, Vasan R. Changing roles of grass-root level health workers in Kerala, India. Health Policy Plan. 2001;16:171–179. doi: 10.1093/heapol/16.2.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fung WY, Chien WT. The effectiveness of a mutual support group for family caregivers of a relative with dementia. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2002;16:134–144. doi: 10.1053/apnu.2002.32951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gitlin LN, Hauck WW, Dennis MP, Winter L. Maintenance of effects of the home environmental skill-building program for family caregivers and individuals with Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders. J Geontol A Biol Sci med Sci. 2005;60:368–374. doi: 10.1093/gerona/60.3.368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific. Asian Population Studies Series No 145: Available at: http://www.unescap.org/pop/publicat/apss145/apss145tc.htm. Accessed October 13, 2005. [PubMed]

- 52.The elderly in the Eastern Mediterranean Region: an overview in ageing Exploding the myths International Year of Older Persons. Alexandria: World Health Organization, Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Regional strategy for health care of the elderly in the Eastern Mediterranean Region:1992–2001. Regional Advisory Panel on Health Care for the Elderly. Alexandria: World Health Organization, Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean; 1994. [Google Scholar]