Abstract

Bicoid (Bcd) is a morphogenetic protein that instructs patterning along the anterior-posterior (A-P) axis in Drosophila embryos. Despite extensive studies, what controls the formation of a normal concentration gradient of Bcd remains an unresolved and controversial question. In this report we show that Bcd protein degradation is mediated by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. We identify a novel F-box protein, encoded by fates-shifted (fsd), that plays an important role in Bcd protein degradation by targeting it for ubiquitination. Embryos from females lacking fsd have an altered Bcd gradient profile, resulting in a shift of the fatemap along the A-P axis. Our study represents a first experimental demonstration that, contrary to an alternative hypothesis, Bcd protein degradation is required for normal gradient formation and developmental fate determination.

Introduction

Morphogens are molecules that form concentration gradients in a developing embryo or tissue to provide positional information to cells and instruct their developmental fates 1-5. The Drosophila morphogenetic protein Bicoid (Bcd) forms a concentration gradient along the anterior-posterior (A-P) axis of the embryo and instructs patterning by activating its downstream target genes in a concentration-dependent manner 6-9. An important question about morphogens relates to the molecular mechanisms that control the formation of a normal gradient. Diffusion and degradation of morphogen molecules are two physical properties critical to both the process of gradient formation and the final outcome of the gradient 1, 5, 10, 11. While the diffusion constant for Bcd molecules in embryos remains highly controversial 12-14, what controls Bcd degradation remains virtually unknown at this time. In this report, we investigate the molecular mechanisms of Bcd protein degradation. We present evidence that Bcd degradation is required for the formation of a normal concentration gradient in embryos and for instructing cells to adopt their normal developmental fates.

Results

Bcd degradation in Drosophila cells is sensitive to proteasome inhibitors

We generated Drosophila S2 cells that stably express an HA-tagged wt Bcd protein from the actin promoter (referred to as the HA-Bcd-expressing stable cells). Western blotting analysis confirmed the expression of the full-length Bcd protein in these cells (Supplementary Information, Fig. S1a online). This HA-Bcd protein can activate transcription of a Bcd-dependent reporter gene in S2 cells 15, demonstrating that it is functionally active. To investigate mechanisms and pathways of Bcd protein degradation, we treated the HA-Bcd-expressing stable cells with various inhibitors. The proteasome inhibitor MG132 increased the total amount of Bcd (Fig. 1a, lane 4; Supplementary Information, Fig. S1b online). Neither Z-LL-H, which is an MG132 analogue and a calpain inhibitor, nor chloroquine diphosphate, which is a lysosome inhibitor, had such an effect (Fig. 1a, lanes 2 and 3). Two additional proteasome inhibitors, lactacystin and epoxomicin, which inhibit proteasome activities through distinct mechanisms 16, 17, also increased the total amount of Bcd (Fig. 1a, lanes 5 and 6). These results suggest that the proteasome-dependent pathway is important for Bcd protein degradation.

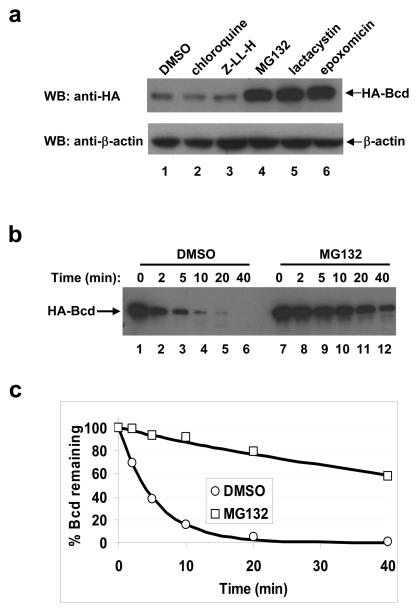

Figure 1. Bcd is degraded through the proteasome-dependent pathway.

(a) Effects of protease inhibitors on the total amount of Bcd in Drosophila S2 cells. The HA-Bcd-expressing stable cells were treated with the indicated inhibitors and Western blotting (WB) was carried out to determine the total amount of HA-Bcd using the HA antibody (top panel). β-actin (bottom panel) represents loading control.

(b) Time course of Bcd degradation in embryonic extracts. HA-Bcd synthesized in an in vitro transcription/translation system was analyzed in embryonic extracts in the presence or absence of MG132 (DMSO represents no MG132 control). Aliquots were taken from reaction tubes at the indicated time points, and HA-Bcd was detected by Western blotting.

(c) Bcd degradation kinetics. Shown are scatter plots between fraction of remaining Bcd protein (quantified from panel b data) and reaction time (see Methods for details). The lines represent the exponential fitting to the experimental data. Throughout this study, all kinetic experiments shown in individual panels were performed side-by-side, and only such side-by-side results within a single panel can be compared. Based on three independent experiments, the estimated half-life of Bcd is increased by 13.10 ± 1.80 fold in the presence of MG132.

Bcd degradation in Drosophila embryonic extracts reveals a role of ubiquitin

To further investigate Bcd degradation mechanisms, we generated Drosophila 0-3 hr embryonic extracts. An HA-Bcd fusion protein was efficiently degraded in these extracts (Fig. 1b, lanes 1-6), but such degradation was significantly inhibited by MG132 (lanes 7-12) or epoxomicin (Supplementary Information, Figs. S1c and d online). Bcd degradation profiles in the presence or absence of MG132 both fitted well with the first order decay function 18 (Fig. 1c), with a respective Adjusted R2 value of 0.999 and 0.981. Data fitting reveals that MG132 extends the estimated half-life of Bcd by 13.1 fold. These results further support our conclusion that Bcd is degraded in a proteasome-dependent manner.

Proteins destined for proteasome-mediated degradation are often poly-ubiquitinated 19-22. Unlike protein degradation in the lysosome, ubiquitination is a process that requires energy from ATP hydrolysis 22. The following two sets of experiments show that Bcd degradation in embryonic extracts is dependent on ATP. First, addition of ATP into the embryonic extracts enhanced Bcd degradation, with a 61% reduction in the estimated half-life of Bcd (Figs. 2a and b). In addition, depletion of ATP from the extracts through the use of hexokinase and glucose led to an attenuated Bcd degradation, extending the estimated half-life of Bcd by 2.3 fold (Figs. 2c and d).

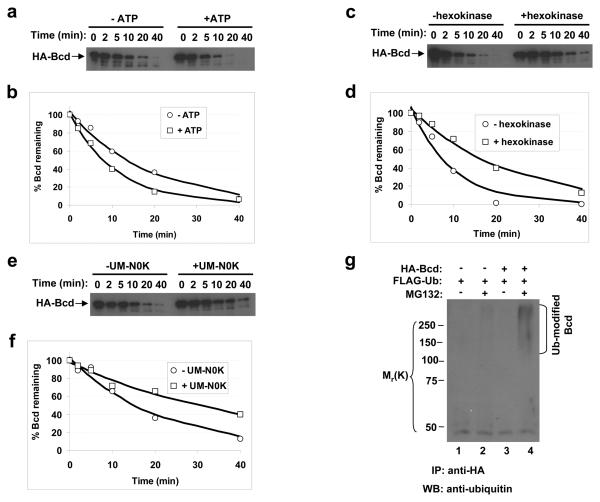

Figure 2. Bcd is ubiquitinated.

(a, c and e) Time course of Bcd degradation in embryonic extracts with or without ATP addition (a), ATP depletion (c) or UM-N0K addition (e). Hexokinase (together with glucose) was used to deplete ATP. For each experiment, aliquots were taken from the reaction tubes at the indicated time and HA-Bcd was detected by Western blotting.

(b, d and f) Fraction of remaining Bcd protein (from panels a, c and e) plotted against reaction time. In each case the lines represent the exponential fitting to the experimental data. Based on three independent experiments, the estimated half-life of Bcd is increased by 1.93 ± 0.35 fold in presence of UM-N0K.

(g) Bcd ubiquitination detected in cells. Whole cell extracts from HEK 293T cells were immuno-precipitated (IP) by an anti-HA antibody and analyzed by Western blotting using the anti-ubiquitin antibody. Ubiquitin-modified Bcd products are marked, and molecular weight standards are shown on the left.

To directly investigate the role of ubiquitin in Bcd degradation, we used a mutant ubiquitin, UM-N0K, which has all of its seven lysine residues mutated to arginines. This mutant ubiquitin can prevent poly-ubiquitination and inhibit ubiquitin-dependent protein degradation 23. If Bcd degradation is indeed dependent on poly-ubiquitination, we would expect this mutant ubiquitin to inhibit Bcd degradation. Our results show that, when UM-N0K was added to the embryonic extracts, Bcd degradation was attenuated, extending its estimated half-life by 1.93 fold (Figs. 2e and f). Together, these results suggest that Bcd is degraded in a proteasome- and ubiquitin-dependent manner.

Bcd is ubiquitinated

To determine whether Bcd is ubiquitinated, we performed an in vivo ubiquitination assay in Human Embryonic Kidney (HEK) 293T cells, which have an efficient ubiquitination system 24. To increase the amount of ubiquitin-modified products, a ubiquitin-expressing plasmid was cotransfected into these cells, which were then treated with MG132 prior to harvest. As shown in Fig. 2g, ubiquitin-modified Bcd protein species (lane 4) were detected in a Bcd- and MG132-dependent manner (see other lanes for controls). These results support the suggestion that Bcd is ubiquitinated.

Identifying a novel F-box protein involved in Bcd degradation

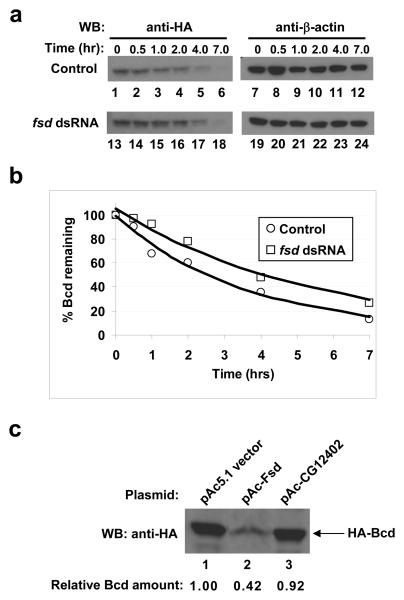

Ubiquitination is catalyzed by three stepwise enzymatic reactions, with the ubiquitin ligase E3 providing substrate specificity 19-22. One group of E3 ligases, the SCF (Skp1-Cul1/Cdc53-F-box protein)-type E3 ligases, plays a role in the turnover of many transcription factors 25-30. The substrate specificity in these multi-protein complexes is conferred by F-box proteins 25, 31, 32. We performed a dsRNAi screening in the HA-Bcd-expressing stable S2 cells on 38 potential Drosophila F-box proteins. The presence of dsRNA targeting a gene, fates-shifted (fsd, CG12765), caused a consistent increase in the total amount of Bcd (Supplementary Information, Fig. S2a, lane 3 online; see lanes 1 and 2 for specificity). We used cycloheximide (CHX) to block translation in the HA-Bcd-expressing stable cells (Fig. 3a) and found that fsd dsRNA treatment increased the estimated half-life of Bcd by 1.5 fold (Fig. 3b). In addition, over-expressing Fsd in S2 cells reduced the total amount of Bcd (42%; Fig. 3c, lane 2; see lanes 1 and 3 for controls). Together, these results show that Fsd plays an important role in regulating Bcd protein stability in Drosophila cells.

Figure 3. Fsd plays a role in Bcd protein degradation.

(a) CHX assay in HA-Bcd-expressing stable cells. Cells were treated first with fsd dsRNA, then with CHX, and harvested at indicated time (of CHX treatment) for Western blotting to detect the total amount of Bcd in cells (left panels). β-actin (right panels) represents loading control.

(b) Fraction of remaining Bcd protein (from panel a and normalized by β-actin intensities) plotted against time after CHX addition. The lines represent exponential fitting to the experimental data.

(c) Over-expression of Fsd enhances Bcd degradation in Drosophila S2 cells transiently transfected with the HA-Bcd expressing plasmid. For each lane, the loading amount had been adjusted by the β-galactosidase activities (measuring transfection efficiency) expressed from a lacZ control plasmid.

Fsd is an F-box protein that directly interacts with both Skp1 and Bcd

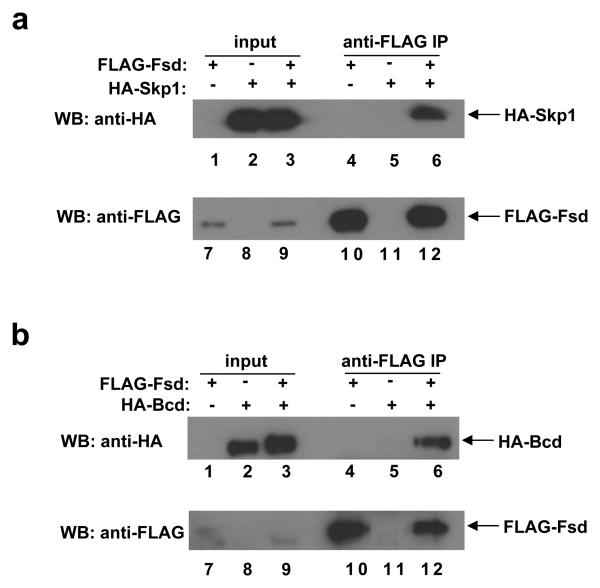

F-box motifs are highly degenerate, lacking a strict primary consensus sequence based on the alignment of 234 sequences used to create the F-box profile in the Pfam database 31. Our alignment of all potential F-box domains in Drosophila derived from the Interpro database further confirms the degenerate nature of the primary sequences of the F-box motif (Supplementary Information, Fig. S3 online). A hallmark of a genuine F-box protein is its ability to interact with Skp1, another component of the SCF complex 25, 31, 32. To determine if Fsd has this property, we performed co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) experiments in HEK 293T cells. As shown in Fig. 4a, HA-Skp1 was specifically co-precipitated by FLAG-Fsd (lane 6; see other lanes for controls), demonstrating that Fsd and Skp1 can physically interact with each other in cells.

Figure 4. Fsd interacts with both Skp1 and Bcd.

(a) A co-IP experiment detecting the interaction between Fsd and Skp1. HEK 293T cells were co-transfected with the indicated combinations of plasmids expressing FLAG-Fsd and HA-Skp1. Anti-FLAG antibody was used to immuno-precipitate FLAG-Fsd in whole cell extracts, followed by Western blotting analyses using anti-HA and anti-FLAG antibodies to detect HA-Skp1 and FLAG-Fsd, respectively.

(b) Same as a, except with the use of a plasmid expressing HA-Bcd (in place of HA-Skp1) to detect the interaction between Bcd and Fsd.

To further evaluate the role of Skp1 in Bcd degradation, we manipulated Skp1 protein levels in the HA-Bcd-expressing stable cells. The total amount of Bcd in these cells was decreased when additional Skp1 (FLAG-Skp1) was expressed (Supplementary Information, Fig. S2b, lane 3 online; see lane 1 for control). As expected, MG132, which inhibits the downstream step of protein degradation, increased the total amount of Bcd to a similar level regardless of the status of additional Skp1 expression (Supplementary Information, Fig. S2b, lanes 1-4 online). In addition, when cells were treated with skpA dsRNA, the estimated half-life of Bcd was extended by 2.5 fold (Supplementary Information, Figs. S2c and d online). Together, our results suggest that both Fsd and Skp1 participate in the Bcd degradation process, presumably working together in a novel Fsd-containing SCF (SCFFsd) E3 ligase.

F-box proteins target their substrates for degradation by recruiting, through direct protein-protein interactions, them to the SCF E3 ligase complexes for ubiquitination 25, 31, 32. To determine whether Bcd is a substrate of the proposed SCFFsd E3 ligase, we performed another co-IP experiment. Our results show that HA-Bcd was specifically co-precipitated by FLAG-Fsd (Fig. 4b, lane 6; see other lanes for controls), demonstrating that Fsd can physically interact with Bcd. Together, these results suggest that Fsd is a bona fide F-box protein that can directly interact with both a component (Skp1) within the proposed SCFFsd complex and its substrate Bcd.

Embryos lacking Fsd exhibit posterior shifts in morphological and molecular markers

Sequence analysis of an fsd cDNA clone (NM_137007.3) predicted a 312-aa protein, consisting of two potential F-box domains (Fig. 5a). Fsd does not contain any other conserved domains that are obvious. fsd transcripts are uniformly distributed in both preblastoderm and gastrulated embryos (Supplementary Information, Figs. S4a and b online), suggesting both maternal and zygotic expression. We obtained a publically available P-element insertion line disrupting fsd, referred to as fsdKG02393. We confirmed that the insertion takes place 15bp downstream of ATG, which effectively disrupts the gene's entire open reading frame (Fig. 5a). The fsdKG02393 flies are homozygous viable, but exhibit a temperature-dependent hatching defect. While the hatching rates of embryos from wt and fsdKG02393 flies were comparable at 25°C (91.3% vs. 81.7%, Supplementary Information, Fig. S4c online), embryos from mutant flies had a significantly reduced hatching rate at 18°C (48.6%, compared with 92% for wt). At 29°C, embryos from fsdKG02393 females (referred to as fsd embryos from now on) had a hatching rate of 0%. Cuticle examination detected mutant embryos with variable A-P patterning defects at 29°C, including missing/fused denticle bands (Supplementary Information, Figs. S5b-d online). Whole mount in situ hybridization analysis also detected mutant embryos with abnormal even-skipped (eve) expression patterns with missing/fused stripes (Supplementary Information, Figs. S5f and g online). These results suggest that the hatching defect observed at 29°C is a consequence of A-P patterning defects caused by the fsd mutation. The hatching defect at 29°C is strictly associated with the maternal mutant genotype (not shown) and, furthermore, mutant flies at non-optimal temperatures (18°C) do not exhibit a significant reduction in survival rates from larvae to pupae or from pupae to adults (Supplementary Information, Fig. S4c online). These results suggest that the primary function of fsd is conferred maternally to embryos.

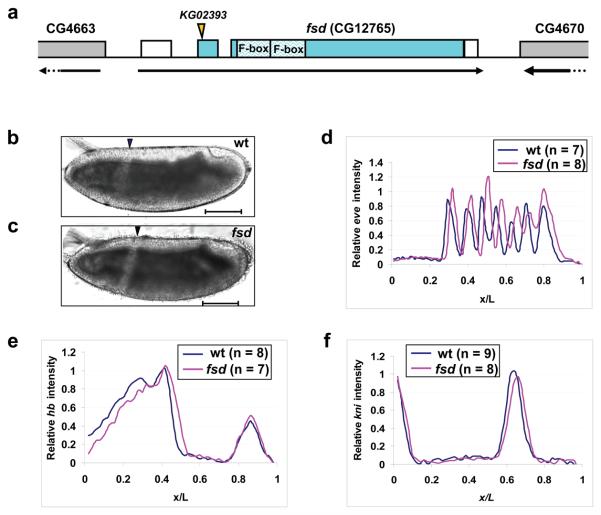

Figure 5. Posterior shift of fatemap along the A-P axis in fsd embryos.

(a) A schematic representation of the fsd gene (not to scale). The arrow under the gene shows the transcriptional direction and the boxes represent annotated exons. Filled sections of the boxes represent the annotated fsd coding sequences, while the unfilled sections represent un-translated regions. The position of the KG02393 insertion and the two F-box domains are marked. Parts of the two annotated neighboring genes are also shown in this schematic diagram.

(b and c) Shown are the midsagittal views of living embryos from w1118 (b) and fsdKG02393 (c) flies at 25 °C imaged under halocarbon oil. Arrowheads represent the CF positions. Scale bar: 100 μm.

(d-f) Shown are average normalized fluorescence intensities of whole mount FISH detecting the transcripts of eve (d), hb (e) and kni (f) in wt (blue) and fsd (red) embryos. See text for further details and Supplementary Information Fig. S6 online for data extracted from individual embryos. The expression stripes 1 to 7 have the following posterior shifts in their respective posterior boundary positions in fsd embryos: 2.2%, 1.9%, 2.9%, 2.8%, 3.4%, 1.5% and 1.1% EL.

Acting as a morphogen instructing A-P patterning, the amount of Bcd directly controls the fatemap of the entire embryo along the A-P axis 33-35. If Fsd plays a role in promoting Bcd protein degradation in embryos as observed in our in vitro assays, fsd embryos may exhibit a posterior shift of the fatemap reflective of an altered amount of Bcd. To directly evaluate this possibility, we measured the position of the cephalic furrow (CF), a morphological marker along the A-P axis and a strong indicator of Bcd protein levels in embryos 13, 34, 36. For experiments described from now on, all embryos were collected at 25°C (unless stated otherwise) to avoid any temperature influence on Bcd gradient formation and embryonic patterning. Figs. 5b and c show that the CF position (in fractional embryo length, x/L) was shifted from 0.343 ± 0.005 (n = 10) in wt embryos to 0.372 ± 0.012 (n = 9) in fsd embryos (p = 4.6 × 10−6, Student's t test). To evaluate molecular decisions, we measured the expression pattern of eve (ref 37) using quantitative fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH). To ensure a direct comparison, experiments and data processing for wt and mutant embryos were performed side-by-side. Fig. 5d shows the mean expression profiles of eve in wt and mutant embryos, revealing a posterior shift for all eve stripes in fsd embryos (see Supplementary Information Figs. S6a and b online for raw data). For example, the first eve stripe is shifted from 0.331 ± 0.014 (n = 7) in wt embryos to 0.353 ± 0.009 (n = 8) in fsd embryos (p = 3.9 × 10−3, Fig. 5d).

To trace the origin of the observed fatemap shift in mutant embryos, we measured expression patterns of gap genes hunchback (hb) and knirps (kni), both of which are direct targets of Bcd 8, 38-44. Again, we conducted side-by-side experiments in wt and mutant embryos for each gene in our quantitative FISH. As shown in Figs. 5e and f, the expression boundaries of both gap genes exhibited a significant posterior shift in fsd embryos (see Supplementary Information Figs. 6c-f online for raw data). Specifically, the hb expression boundary had a posterior shift of ~3% embryo length (EL), from 0.450 ± 0.008 (n = 8) in wt embryos to 0.479 ± 0.018 (n = 7) in fsd embryos (p = 1.4 × 10−3, Fig. 5e). The kni expression boundary was shifted toward the posterior by ~2% EL, from 0.671 ± 0.010 (n = 9) in wt embryos to 0.689 ± 0.017 (n = 8) in fsd embryos (p = 1.3 × 10−2, Fig. 5f). Together, these results demonstrate that a maternal loss of fsd function results in a posterior shift of both morphological and molecular markers along the A-P axis.

fsd and bcd interact genetically

The observed fatemap shift in fsd embryos is supportive of a direct role of Fsd in targeting Bcd for degradation in embryos. To further test this hypothesis, we conducted a genetic interaction analysis in embryos from bcdE1/+ females that are either wt or mutant for fsd. Our results show that the anterior fatemap shift caused by maternal bcd dosage reduction is rescued partially by eliminating fsd maternally (Supplementary Information Figs. S7a-c online). These results demonstrate an interaction, genetically, between fsd and bcd in regulating developmental fate specification along the A-P axis.

fsd embryos have an altered Bcd gradient profile

To directly determine whether Fsd plays a role in Bcd gradient formation, we conducted a quantitative whole mount immunostaining analysis with anti-Bcd antibodies in wt and mutant embryos 45. We used raw, un-normalized Bcd fluorescence intensities that were captured linearly with background directly measured under identical experimental conditions. Figs. 6a and b show raw Bcd intensity data extracted from individual wt and fsd embryos that were stained, imaged and analyzed side-by-side. Also shown in these figures are the measured background intensities. To evaluate the shape of the Bcd gradient profiles, we calculated and compared the length constant (λ) values of either the average Bcd profiles from wt and mutant embryos or values from individual embryos. In a simple diffusion model 1, 5, 46, λ of an exponential profile is a function of the effective diffusion coefficient (D) and the effective degradation rate of the morphogen molecules (ω), λ2 =D/ω. Since Bcd protein itself has not been altered in fsd embryos, D is expected to remain unaffected by fsd mutation, which allows us to estimate the relative ω values in wt and mutant embryos based on their measured λ values.

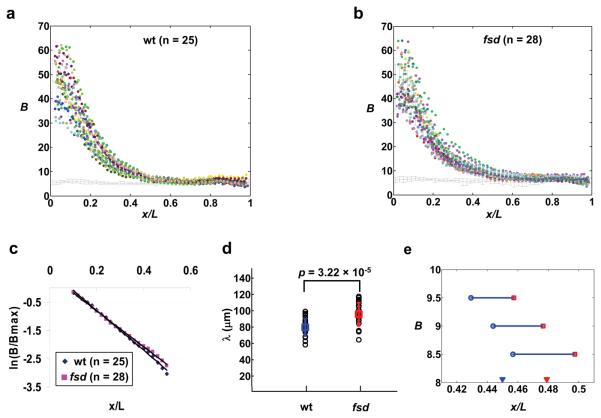

Figure 6. Bcd gradient profiles in wt and fsd embryos.

(a and b) Shown are raw Bcd intensity profiles extracted from individual wt (a) and fsd (b) embryos. The mean intensities and error bars are shown. Each color represents data from an individual embryo. The line at the bottom represents measured background intensities with errors bars shown.

(c) ln(B/Bmax) plotted against x/L for average Bcd profiles from wt (a) and fsd (b) embryos. Both B and Bmax are background-subtracted as necessary, without any further adjustments. The solid lines represent linear fits for Bcd profiles from wt (y = −7.02x + 0.61, Adjusted R2 = 0.997) and fsd (y = −6.31x + 0.45, Adjusted R2 = 0.998) embryos.

(d) Shown are λ values calculated from Bcd intensity profiles of individual wt and fsd embryos. The mean values, error bars and the p value from Student's t test are also shown.

(e) Shown are A-P positions at which the mean Bcd profiles (raw intensities without adjustments) from wt and fsd embryos cross concentration thresholds near the hb boundary. The measured average hb boundary positions in these embryos are marked with solid arrowheads for reference. Wt embryos are shown in blue and fsd embryos in red.

Fig. 6c shows a ln(B/Bmax) plot as a function of A-P position x/L. Both B and Bmax are from average Bcd profiles of wt and fsd embryos and are background subtracted (as necessary) without any further adjustments. The ln transformation converts an exponential function to a linear function 42. Here we perform a linear fit within the range of x/L = 0.1 to 0.5, where the Bcd intensity data are least sensitive to experimental and background measurement errors 45, 46. We also exclude data from the most anterior part of the embryo where Bcd profiles are known to deviate from an exponential function 10, 42, 45. The linear fitting (Fig. 6c) exhibited a smaller slope in fsd embryos than in wt embryos, suggesting a larger λ value in fsd embryos. To further compare Bcd profiles, we calculated λ values for individual wt and mutant embryos (Fig. 6d). The calculated λ values increased from 78.94 ± 12.93 μm (n = 25) in wt embryos to 95.95 ± 14.03 μm (n = 28) in fsd embryos (p = 3.22×10−5, Fig. 6d). These results (and Figs. 5 and S6) provide in vivo evidence that Fsd plays a role in regulating Bcd protein stability and determining developmental fates along the A-P axis.

Discussion

Advancing the morphogen concept requires an understanding of not only how cells respond to the positional information encoded by the morphogen gradients but also how such gradients are established. According to a widely accepted view 1, the formation of a concentration gradient requires a localized source of morphogen production, coupled with diffusion and degradation of the morphogen molecules. However, recent studies question whether the formation of a normal concentration gradient of Bcd in embryos requires either diffusion or decay of Bcd molecules 47, 48. Prior to our current work, it was not known how Bcd molecules are degraded, making it difficult to evaluate the role of Bcd protein degradation in gradient formation in vivo. We report for the first time that Bcd is degraded through the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. The identification of a novel F-box gene, fsd, makes it possible to experimentally perturb Bcd degradation in vivo and investigate its role on Bcd gradient formation and developmental fate determination.

The Bcd gradient profile in fsd embryos has a larger λ value than in wt embryos, demonstrating that, contrary to a recent proposal 47, Bcd degradation is required for normal gradient formation. Our observed difference in λ values corresponds to, in a simple diffusion model, a ~48% increase in Bcd stability in fsd embryos, a difference sufficient to cause significant shifts in morphological and molecular markers (Fig. 5). We note that, unlike λ, Bmax in wt and fsd embryos did not exhibit a significant difference (44.32 ± 9.10 and 42.53 ± 9.19, respectively, p = 0.63, Student's t test). While λ is a function of D and ω in a simple diffusion model, the steady state amount of morphogen molecules at the source is also a function of D and ω, but additionally, it is dependent on the morphogen production rate J 1, 5, 46. Since the Bcd production site (i.e., bcd mRNA location) is not restricted to a single point as assumed in the idealized simple diffusion model 10, λ should represent a more reliable parameter (than, e.g., Bmax) in evaluating the relative effective degradation rates of Bcd.

The hb expression boundary in fsd embryos exhibits a ~3% EL shift toward the posterior. This shift is consistent with the shift of the positional information encoded by the Bcd gradient in fsd embryos (Fig. 6e). These results, together with those presented elsewhere 45, 46, 49, demonstrate that the hb expression boundary is primarily determined by the positional information provided by the Bcd gradient. Although gene regulatory networks represent important mechanisms for maintaining or refining gene expression patterns 11, 46, 50, 51, our results suggest that early decisions in A-P patterning, such as hb expression, are controlled primarily by the positional information encoded by the Bcd gradient. The ~3% EL hb boundary shift in fsd embryos matches the observed CF shift (~3% EL), indicating that early decisions in gene expression are faithfully passed down to the morphological level. We note that the ~3% EL hb boundary shift in fsd embryos, though seemingly modest, is rather significant when compared with the observed shift (~7% EL) caused by the doubling of the maternal bcd gene dose to four copies 42. A ~3% EL shift, when expressed in absolute length, is comparable to the difference between our measured λ values in wt and mutant embryos. We also note that the fatemap shift in fsd embryos was detected at 25°C. The hatching defect of fsd embryos at 29°C represents a manifestation of more severe A-P patterning defects (Supplementary Information, Fig. S5 online), likely reflective of the complex effects of temperature on both Bcd gradient formation (i.e., degradation and diffusion) and other relevant processes. Finally, we note that the fsdKG02393 allele used throughout our work is likely a null allele because it is indistinguishable from an allele, fsd5-7, that has the entire fsd coding sequence deleted (Supplemental Information, Fig. S8).

SCF E3 ligases regulate many biological processes such as DNA replication, transcription, signal transduction, cell proliferation and death, tissue growth and patterning 25, 26, 31, 32. Our study identifies a new F-box protein (encoded by fsd) that plays a role in Bcd gradient formation and developmental fate specification. Our study thus expands the list of biological processes that SCF E3 ligases regulate. Fsd directly interacts with both its substrate Bcd and an SCF component Skp1, suggesting that Bcd is targeted for degradation by an Fsd-containing SCF complex, SCFFsd, that acts as an E3 ubiquitin ligase. We currently do not know whether Fsd may have other substrates. Identification of additional substrates of Fsd, if any, will provide a more comprehensive understanding of the biological functions of this novel F-box protein.

How a normal Bcd concentration gradient is formed in early embryos remains an open question currently under intense debate 10, 13, 14, 47-49, 52, 53. One particular aspect of the debate focuses on the roles of the nucleus. While some studies suggest that nuclei play important roles in Bcd degradation 7 and proper gradient formation 13, 54, others suggest that the shaping of a normal Bcd gradient is independent of nuclei 55. Fsd is broadly distributed in cells with a primary localization to the cytoplasm (Supplementary Information, Figs. S4d-f online), consistent with the notion that cytoplasm plays a role in Bcd degradation. However, our recent studies show that dCBP, a Bcd-interacting transcription cofactor 56, 57, affects Bcd gradient profile in embryos 46, suggesting that nuclei also contribute to Bcd degradation and gradient formation. Although efficient Bcd degradation requires Fsd both in vitro and in vivo, we consider it unlikely that SCFFsd is the only E3 ligase for Bcd. Identifying additional E3 ligases, particularly those with a primary localization to the nucleus, should help settle the on-going controversy regarding the role of nuclei in Bcd gradient formation.

Methods

Fly lines, plasmids, and cells

The fsdKG02393 flies were obtained from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (stock number 12983). The following vectors were used in this study. pGEM3 (Promega) was used as a template for in vitro transcription/translation. The pAc5.1/V5-His C vector (Invitrogen) containing the Drosophila actin 5C promoter was used to constitutively express proteins in Drosophila S2 cells. The pcDNA3 vector (Invitrogen) containing the Human Cytomegalovirus Immediate-early (CMV) promoter was used for over-expressing proteins in HEK 293T cells. All plasmids used in this study were generated by standard cloning methods. Drosophila S2 and HEK 293T cells were cultured in Schneider's Drosophila medium (Invitrogen) and Dulbecco's modification of Eagle's medium (Cellgro), respectively, both containing 10% fetal calf serum (Invitrogen) and 1×antibiotic-antimycotic (Invitrogen). Transfection in both cells was performed using the FuGENE® HD transfection reagent (Roche) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Stable Drosophila S2 cells and protein stability assay

Drosophila S2 cells that stably express HA-Bcd were generated as described previously 58. The following is a list of inhibitors (sources; final concentrations) for treating cells: chloroquine diphosphate (Sigma; 500 μM), Z-LL-H (Peptides International; 100 μM), MG132 (Boston Biochem; 75 μM), lactacystin (Calbiochem; 10 μM), epoxomicin (Calbiochem; 300 nM), and CHX (Sigma; 100 μg/ml). For transient assays, a lacZ reporter was used to normalize transfection efficiency 15.

Protein degradation assay in Drosophila embryonic extracts

Drosophila embryonic extracts (0-3 hr w1118) were prepared as described previously 59, diluted to a final concentration of 10 mg/ml and stored at −80 °C prior to use. HA-Bcd protein used in protein degradation assays was translated in vitro using the TNT® quick coupled transcription/translation system (Promega). Degradation reactions were performed at 30 °C, with or without the following (at given final concentrations): MG132 (500 μM), epoxomicin (100 μM), Mg-ATP (Boston Biochem; 5 mM), UM-N0K (Boston Biochem, 0.67 μg/μl), glucose (Sigma; 10 mM) and hexokinase (Sigma; 0.3 U/μl). We have noticed that the protein degradation activities of the stored embryonic extracts varied somewhat. Thus, all kinetic experiments with specific treatments included a side-by-side (at all steps) no-treatment control. Only comparisons between side-by-side assays are meaningful and, thus, no comparisons were made (or should be made) between experiments. Despite this variability, the effects of different treatments on Bcd stability are highly reproducible between independent experiments (see legends to Figs. 1 and 2 for more information).

Western blot and protein quantifications

For detecting total protein amounts in cells, cells were directly boiled in 1 × SDS-PAGE loading buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 100 mM dithiothreitol, 2% SDS, 10% glycerol, 0.1% bromophenol blue) for 8 min, with a brief vortexing every 2 min. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to Immun-Blot™ PVDF membrane (Bio-Rad) for Western blotting using appropriate primary antibodies and HRP-conjugated second antibodies. Western blotting signals were visualized by ECL plus Western blotting detection reagents (GE Healthcare). HA-tagged and FLAG-tagged proteins were detected by anti-HA (Covance) and anti-FLAG (Sigma) primary antibodies, respectively; anti-β-actin antibody (Abcam) was used to detect β-actin as loading control whenever necessary. The protein bands detected in Western blotting were quantified as follows. X-ray films were scanned with the HP Scanjet 4070 Photosmart scanner, followed by analysis using the Scion image software. A rectangular box of the same size was chosen to cover the individual bands of interest, with mean intensities determined by the software. Background intensity was obtained by placing the same-sized rectangular box in a blank lane at the same position as in experimental lanes. To estimate the half-life of Bcd in the embryonic extracts, we plotted the Bcd remaining amount (fraction of Bcd intensity at time zero) against the reaction time. The data were then fitted to the exponential decay equation (y = a × e−bx) using the Matlab software. The resulting ln2 / b values represent the estimated half-life of Bcd.

In vivo ubiquitination and co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) assays

For ubiquitination assay, the HA-Bcd-expressing plasmid was transiently transfected into HEK 293T cells, along with a second plasmid expressing an FLAG-tagged ubiquitin. Cell lysates were prepared and incubated with anti-HA monoclonal antibody (Roche) and protein G Sepharose™ 4 fast flow beads (GE Healthcare). Immunoprecipitates were resolved by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting performed using anti-ubiquitin antibody (Zymed). For co-IP assays, HEK 293T cells were co-transfected with plasmids expressing FLAG-Fsd and HA-Skp1 (or HA-Bcd). Cell lysates were incubated with anti-FLAG antibody (Sigma) and protein G Sepharose™ 4 fast flow beads, followed by Western blotting using appropriate antibodies.

dsRNAi generation and screening in the HA-Bcd-expressing stable S2 cells

38 potential Drosophila F-box proteins for dsRNAi screening 60 were derived from the Interpro database from the European Bioinformatics Institute. Primers used for PCR amplification of each gene fragment were chosen from the amplicon database of the Drosophila RNAi Screening Center at Harvard Medical School. In order to transcribe dsRNAs in vitro from the PCR fragments, each primer contained a T7 RNA polymerase binding site (TAATACGACTCACTATAGGG) at 5′. The dsRNAs were generated from the MEGASCRIPT T7 transcription kit (Ambion) and purified by the RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen). To minimize the effect of plate-to-plate variations and increase the reliability of assays during screening, fold change in Bcd levels for each sample was calculated by dividing a sample's intensity by the mean of all of the 12 samples on a given plate, with all experimental and quantification steps performed strictly on a side-by-side basis for all samples on a single plate.

Embryo staining, imaging and intensity measurement

0-4 hr embryos were collected at stated temperatures, fixed and stained for mRNA using digoxigenin (Roche)-labeled antisense RNA probe as previously described 61, 62 with the following modifications: embryos were post-fixed with 10% formaldehyde (Fisher Scientific) and hybridization was performed in a buffer containing 0.3% SDS (40 hrs incubation) without protease K pre-treatment. Cy3-AffiniPure Donkey anti-mouse IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch) was used as the secondary antibody in our staining. Imaging and quantification were described previously 45, with all images captured within a linear range under identical settings in a single image cycle (for both wt and mutant embryos that were stained for a gene of interest) to minimize measurement errors. To measure the FISH intensities in cytoplasm, a circular window of the size of 61 pixels was used to slide along embryo edge immediately outside of nuclear layer (basally for hb and kni; apically for eve) during the automated image processing. It has been shown that gap gene and segmentation gene expression patterns evolve during nuclear cycle 14 50, 63. To minimize such effects and allow accurate comparison between wt and mutant embryos, we selected embryos within short developmental windows with a peak expression level for each gene analyzed. Specifically, we selected embryos at early nuclear cycle 14 with a nuclear height : width ratio of 1.3 : 1 to 1.7 : 1 for hb and kni expression patterns as described previously 45. For hb expression, embryos were further selected to have a posterior hb expression at a normalized level between 0.25 and 0.75. For kni expression, embryos were further selected to ensure no detectable expression stripe at the x/L position of ~0.25. The segmentation gene eve reaches its peak expression at a later time than the gap genes, and we selected embryos as a stage (prior to the onset of gastrulation) shown to have highly precise eve pattern 63. To further increase the precision of developmental time for eve analysis, we selected embryos that had the seventh stripe level > 75% of the first stripe level. The measured boundary positions for all three genes were highly precise within each group of embryos, with a standard deviation that is less than that of the observed posterior shifts between wt and fsd embryos in each case.

Embryo staining, imaging and intensity measurements with anti-Bcd antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) were as described previously 45. To compare λ values of Bcd profiles from wt and fsd embryos, we first analyzed their mean Bcd intensity profiles as a function of x/L. Bcd intensities used in this analysis were background-subtracted without further adjustments. The linear fit of ln(B/Bmax) was conducted using the Matlab software. The λ values in individual embryos were calculated as described 45. In an alternative fitting, we used the equation of B = Bmaxe−x/λ + C and obtained consistent results; the mean λ values calculated from Bcd profiles of individual wt and fsd embryos are 75.08 ± 9.90 μm and 94.20 ± 16.41 μm (p = 5.9 × 10−6), respectively.

Immunocytochemistry

Drosophila S2 cells were cultured on a Lab-Tek II chamber slide and transfected with the HA-Fsd-expressing plasmid. Cells were fixed, permeabilized, incubated with anti-HA antibody (1:100 dilution) and Alexa Fluor®488 goat anti-mouse IgG (1:400 dilution), and imaged using confocal microscopy. TO-PRO-3 dye (1 μM) was used for staining nuclei.

Statistical analysis

All relevant experimental values represent mean values and standard deviations, with n representing the number of independent samples. p values were calculated by the Student's t test function (two-tailed) using the Matlab software (MathWorks). Exponential and linear fitting was done through the curve fitting function of the software and the Adjusted R2 values 64 were calculated to determine how well a fitting is (a perfect fit has a value of 1).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank members of our groups at CCHMC, in particular Feng He, David Cheung, Wen Dui, and Jingyuan Deng, for discussions and assistance, Xinhua Lin's lab for some of the primers used in our dsRNAi screening, and anonymous reviewers for constructive suggestions. This work was supported in part by grants from NIH and NSF (to JM).

Footnotes

Author Contributions

JL and JM conceived and designed the study; JL performed all experiments and analysis; JL and JM interpreted the data; JL generated all figures; JL and JM wrote and approved the paper.

References

- 1.Wolpert L. Positional information and the spatial pattern of cellular differentiation. J. Theor. Biol. 1969;25:1–47. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5193(69)80016-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kerszberg M, Wolpert L. Specifying positional information in the embryo: looking beyond morphogens. Cell. 2007;130:205–209. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lander AD. Morpheus unbound: reimagining the morphogen gradient. Cell. 2007;128:245–256. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martinez Arias A, Hayward P. Filtering transcriptional noise during development: concepts and mechanisms. Nat Rev Genet. 2006;7:34–44. doi: 10.1038/nrg1750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wartlick O, Kicheva A, Gonzalez-Gaitan M. Morphogen gradient formation. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2009;1:a001255. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a001255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ephrussi A, Johnston D. Seeing is believing. The bicoid morphogen gradient matures. Cell. 2004;116:143–152. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00037-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Driever W, Nüsslein-Volhard C. A gradient of bicoid protein in Drosophila embryos. Cell. 1988;54:83–93. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90182-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Struhl G, Struhl K, Macdonald P. The gradient morphogen bicoid is a concentration-dependent transcriptional activator. Cell. 1989;57:1259–1273. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90062-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Driever W, Thoma G, Nüsslein-Volhard C. Determination of spatial domains of zygotic gene expression in the Drosophila embryo by the affinity of binding site for the bicoid morphogen. Nature. 1989;340:363–367. doi: 10.1038/340363a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deng J, Wang W, Lu LJ, Ma J. A two-dimensional simulation model of the Bicoid gradient in Drosophila. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e10275. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010275. PMID: 20422054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bergmann S, et al. Pre-steady-state decoding of the Bicoid morphogen gradient. PLoS biology. 2007;5:e46. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gregor T, Bialek W, van Steveninck RR, Tank DW, Wieschaus EF. Diffusion and scaling during early embryonic pattern formation; Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America; 2005. pp. 18403–18407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gregor T, Wieschaus EF, McGregor AP, Bialek W, Tank DW. Stability and nuclear dynamics of the bicoid morphogen gradient. Cell. 2007;130:141–152. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Porcher A, et al. The time to measure positional information: maternal hunchback is required for the synchrony of the Bicoid transcriptional response at the onset of zygotic transcription. Development. 2010;137:2795–2804. doi: 10.1242/dev.051300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhao C, et al. The activity of the Drosophila morphogenetic protein Bicoid is inhibited by a domain located outside its homeodomain. Development. 2002;129:1669–1680. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.7.1669. PMID: 11923203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fenteany G, et al. Science. Vol. 268. New York, N.Y: 1995. Inhibition of proteasome activities and subunit-specific amino-terminal threonine modification by lactacystin; pp. 726–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meng L, et al. Epoxomicin, a potent and selective proteasome inhibitor, exhibits in vivo antiinflammatory activity; Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America; 1999. pp. 10403–10408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Belle A, Tanay A, Bitincka L, Shamir R, O'Shea EK. Quantification of protein half-lives in the budding yeast proteome; Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America; 2006. pp. 13004–13009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pickart CM. Mechanisms underlying ubiquitination. Annu Rev Biochem. 2001;70:503–533. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.70.1.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pickart CM, Eddins MJ. Ubiquitin: structures, functions, mechanisms. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1695:55–72. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2004.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Herrmann J, Lerman LO, Lerman A. Ubiquitin and ubiquitin-like proteins in protein regulation. Circ Res. 2007;100:1276–1291. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000264500.11888.f0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ciechanover A. Proteolysis: from the lysosome to ubiquitin and the proteasome. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:79–87. doi: 10.1038/nrm1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hershko A, Ganoth D, Pehrson J, Palazzo RE, Cohen LH. Methylated ubiquitin inhibits cyclin degradation in clam embryo extracts. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:16376–16379. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hsu T, McRackan D, Vincent TS, Gert de Couet H. Drosophila Pin1 prolyl isomerase Dodo is a MAP kinase signal responder during oogenesis. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:538–543. doi: 10.1038/35078508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Deshaies RJ. SCF and Cullin/Ring H2-based ubiquitin ligases. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1999;15:435–467. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.15.1.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Conaway RC, Brower CS, Conaway JW. Science. Vol. 296. New York, N.Y: 2002. Emerging roles of ubiquitin in transcription regulation; pp. 1254–1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Muratani M, Kung C, Shokat KM, Tansey WP. The F box protein Dsg1/Mdm30 is a transcriptional coactivator that stimulates Gal4 turnover and cotranscriptional mRNA processing. Cell. 2005;120:887–899. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.von der Lehr N, et al. The F-box protein Skp2 participates in c-Myc proteosomal degradation and acts as a cofactor for c-Myc-regulated transcription. Molecular cell. 2003;11:1189–1200. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00193-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kornitzer D, Raboy B, Kulka RG, Fink GR. Regulated degradation of the transcription factor Gcn4. EMBO J. 1994;13:6021–6030. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06948.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jiang J, Struhl G. Regulation of the Hedgehog and Wingless signalling pathways by the F-box/WD40-repeat protein Slimb. Nature. 1998;391:493–496. doi: 10.1038/35154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kipreos ET, Pagano M. The F-box protein family. Genome Biol. 2000;1 doi: 10.1186/gb-2000-1-5-reviews3002. REVIEWS3002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ho MS, Tsai PI, Chien CT. F-box proteins: the key to protein degradation. J Biomed Sci. 2006;13:181–191. doi: 10.1007/s11373-005-9058-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Frohnhöfer HG, Nüsslein-Volhard C. Organization of anterior pattern in the Drosophila embryo by the maternal gene bicoid. Nature. 1986;324:120–125. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Berleth T, et al. The role of localization of bicoid RNA in organizing the anterior pattern of the Drosophila embryo. EMBO J. 1988;7:1749–1756. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb03004.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Driever W, Siegel V, Nüsslein-Volhard C. Autonomous determination of anterior structures in the early Drosophila embryo by the bicoid morphogen. Development. 1990;109:811–820. doi: 10.1242/dev.109.4.811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Driever W, Nüsslein-Volhard C. The bicoid protein determines position in the Drosophila embryo in a concentration dependent manner. Cell. 1988;54:95–104. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90183-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Small S, Kraut R, Hoey T, Warrior R, Levine M. Transcriptional regulation of a pair-rule stripe in Drosophila. Genes & Devel. 1991;5:827–839. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.5.827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rivera-Pomar R, Jackle H. From gradients to stripes in Drosophila embryogenesis: filling in the gaps. TIG. 1996;12:478–483. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(96)10044-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Driever W, Nüsslein-Volhard C. Bicoid protein is a positive regulator of hunchback transcription in the early Drosophila embryo. Nature. 1989;337:138–143. doi: 10.1038/337138a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Perkins TJ, Jaeger J, Reinitz J, Glass L. Reverse engineering the gap gene network of Drosophila melanogaster. PLoS computational biology. 2006;2:e51. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0020051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schaeffer V, Janody F, Loss C, Desplan C, Wimmer EA. Bicoid functions without its TATA-binding protein-associated factor interaction domains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:4461–4466. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.8.4461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Houchmandzadeh B, Wieschaus E, Leibler S. Establishment of developmental precision and proportions in the early Drosophila embryo. Nature. 2002;415:798–802. doi: 10.1038/415798a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Crauk O, Dostatni N. Bicoid determines sharp and precise target gene expression in the Drosophila embryo. Curr Biol. 2005;15:1888–1898. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.09.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rivera-Pomar R, Lu X, Taubert H, Perrimon N, Jackle H. Activation of posterior gap gene expression in the Drosophila blastoderm. Nature. 1995;376:253–256. doi: 10.1038/376253a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.He F, et al. Probing intrinsic properties of a robust morphogen gradient in Drosophila. Dev Cell. 2008;15:558–567. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.09.004. PMID: 18854140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.He F, et al. Shaping a morphogen gradient for positional precision. Biophys. J. 2010;99:697–707. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.04.073. PMID: 20682246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Coppey M, Berezhkovskii AM, Kim Y, Boettiger AN, Shvartsman SY. Modeling the bicoid gradient: diffusion and reversible nuclear trapping of a stable protein. Developmental biology. 2007;312:623–630. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.09.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Spirov A, et al. Formation of the bicoid morphogen gradient: an mRNA gradient dictates the protein gradient. Development. 2009;136:605–614. doi: 10.1242/dev.031195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.He F, et al. Distance measurements via the morphogen gradient of Bicoid in Drosophila embryos. BMC Dev Biol. 2010;10:80. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-10-80. PMID: 20678215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jaeger J, et al. Dynamic control of positional information in the early Drosophila embryo. Nature. 2004;430:368–371. doi: 10.1038/nature02678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Manu, et al. Canalization of gene expression in the Drosophila blastoderm by gap gene cross regulation. PLoS biology. 2009;7:e1000049. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lucchetta EM, Vincent ME, Ismagilov RF. A precise Bicoid gradient is nonessential during cycles 11-13 for precise patterning in the Drosophila blastoderm. PLoS One. 2008;3:e3651. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hecht I, Rappel WJ, Levine H. Determining the scale of the Bicoid morphogen gradient; Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America; 2009. pp. 1710–1715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gregor T, McGregor AP, Wieschaus EF. Shape and function of the Bicoid morphogen gradient in dipteran species with different sized embryos. Developmental biology. 2008;316:350–358. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.01.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Grimm O, Wieschaus E. The Bicoid gradient is shaped independently of nuclei. Development. 2010;137:2857–2862. doi: 10.1242/dev.052589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fu D, Ma J. Interplay between positive and negative activities that influence the role of Bicoid in transcription. Nucleic acids research. 2005;33:3985–3993. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki691. PMID: 16030350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fu D, Wen Y, Ma J. The co-activator CREB-binding protein participates in enhancer-dependent activities of Bicoid. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:48725–48733. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407066200. PMID: 15358774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Forler D, et al. An efficient protein complex purification method for functional proteomics in higher eukaryotes. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21:89–92. doi: 10.1038/nbt773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Crevel G, Cotterill S. DNA replication in cell-free extracts from Drosophila melanogaster. EMBO J. 1991;10:4361–4369. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb05014.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Clemens JC, et al. Use of double-stranded RNA interference in Drosophila cell lines to dissect signal transduction pathways; Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America; 2000. pp. 6499–6503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tautz D, Pfeifle C. A non-radioactive in situ hybridization method for the localization of specific RNAs in Drosophila embryos reveals translational control of the segmentation gene hunchback. Chromosoma. 1989;98:81–85. doi: 10.1007/BF00291041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kosman D, et al. Science. Vol. 305. New York, N.Y: 2004. Multiplex detection of RNA expression in Drosophila embryos; p. 846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Surkova S, et al. Characterization of the Drosophila segment determination morphome. Developmental biology. 2008;313:844–862. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.10.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lattin J, Carroll JD, Green PE. Analyzing multivariate data. Thompson Books/Cole; Pacific Grove, CA: 2003. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.