Abstract

The aim of this study was to evaluate the functional efficacy of retinal progenitor cell (RPC) containing sheets with BDNF microspheres following subretinal transplantation in a rat model of retinal degeneration.

Sheets of E19 RPCs derived from human placental alkaline phosphatase (hPAP) expressing transgenic rats were coated with PLGA (Poly-lactide-co-glycolide) microspheres containing brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and transplanted into the subretinal space of S334ter-line-3 rhodopsin retinal degenerate rats. Controls received transplants without BDNF or BDNF microspheres alone. Visual function was monitored using optokinetic head-tracking behavior. Visually evoked responses to varying light intensities were recorded from the superior colliculus (SC) by electrophysiology at 60 days after surgery. Frozen sections were studied by immunohistochemistry for photoreceptor and synaptic markers.

Visual head tracking was significantly improved in rats that received BDNF-coated RPC sheets. Relatively more BDNF treated transplanted rats (80%) compared to non-BDNF transplants (57%) responded to a “low light” intensity of 1 cd/m2in a confined SC area. With bright light, the onset latency of SC responses was restored to a nearly normal level in BDNF treated transplants. No significant improvement was observed in the BDNF-only and no surgery transgenic control rats. The bipolar synaptic markers mGluR6 and PSD-95 showed normal distribution in transplants and abnormal distribution of the host retina, both with or without BDNF-treatment. Red-green cones were significantly reduced in the host retina overlying the transplant in the BDNF -treated group.

In summary, BDNF coating improved the functional efficacy of RPC grafts. The mechanism of the BDNF effects - either promoting functional integration between the transplant and the host retina and/or synergistic action with other putative humoral factors released by the RPCs - still needs to be elucidated.

Keywords: retinal transplantation, superior colliculus, head-tracking behavior, BDNF microsphere, retinal progenitor cells, S334ter

Introduction

Retinal degenerations such as age related macular degeneration and retinitis pigmentosa lead to irreversible vision loss. Animal models of retinal degeneration have allowed investigators to better elucidate the sequence of physiological and biochemical changes associated with these diseases (Jones and Marc, 2005; Marc, et al., 2003). These studies have also provided investigators with information to assist in optimizing therapeutic strategies aimed at preventing visual loss and or restoring lost vision. Therapeutic interventions in animal models, including growth factor treatment, gene therapy, retinal prosthetics and retinal cell transplantation, have been presumed to improve visual sensitivity (Aramant and Seiler, 2002; Aramant and Seiler, 2004; Chaum, 2003; Delyfer, et al., 2004; Loewenstein, et al., 2004; Lund, et al., 2001) by delaying the progression of the disease and/or by rescuing the remaining host photoreceptors. Some studies of retinal sheet transplants have suggested that transplanted photoreceptors may also contribute directly to the visual restoration (Aramant and Seiler, 2004; Seiler, et al., 2005). After injecting freshly harvested retinal progenitor cells in the rho−/− mouse, increased ganglion cell responses and pupillary reflexes have been interpreted as visual improvements (MacLaren, et al., 2006), similar to previous results by other groups(Kwan, et al., 1999; Radner, et al., 2002). Clinical retinal sheet transplantation studies also demonstrated an improvement in visual sensitivity in an RP patient (Radtke, et al., 2004) that is still maintained after 5 years (Radtke et al., 2007, IOVS 47: ARVO e-abstract 3658; unpublished observations).

Our group has developed a specially designed instrument and procedure to deliver sheets of fetal retinal neuroblastic progenitor cells into the subretinal space (Aramant and Seiler, 2002; Aramant and Seiler, 2004). Such transplants develop both inner and outer segments (Seiler and Aramant, 1998; Seiler, et al., 1999), show a shift in the distribution of phototransduction proteins according to the light cycle (Seiler, et al., 1999) and remain healthy for many months. In four different retinal degeneration models, such transplants have been shown to restore visual responses in the superior colliculus (SC) after long survival times of 2 – 8 months (Arai, et al., 2004; Sagdullaev, et al., 2003; Thomas, et al., 2004a; Woch, et al., 2001). Synaptic connectivity between transplants and host retina has been demonstrated by trans-synaptic virus tracing (Seiler, et al., 2005). The visually responsive site in the SC can be traced back to the retinal transplant by trans-synaptic virus tracing (Seiler et al., 2005, IOVS, 45: ARVO E-abstract 4164; manuscript submitted), indicating that the area of transplant in the retina is the origin of visual restoration in the SC. However, in most transplantation experiments, a considerable level of visual restoration was apparent only in a very small SC area indicating that area of integration between the transplant and the host retina is limited.

Among the various neurotrophins involved in the development and integration of the central nervous system (CNS), the modulatory influence of BDNF is well established, especially during the development of the visual sensory system (Berardi, 2004). Studies performed in normal and retinal degenerate rat models demonstrate that BDNF has a neuro-protective role (Chaum, 2003; Gauthier, et al., 2005; Ikeda, et al., 2003; Keegan, et al., 2003; Lawrence, et al., 2004; Nakazawa, et al., 2002; Paskowitz, et al., 2004). Therefore, the present investigation evaluates the possible role of BDNF in promoting the functional efficacy of the retinal neuroblastic sheets transplanted into the subretinal space of retinal degenerative rats.

Materials and Methods

Animals

For all experimental procedures, animals were treated in accordance with the NIH guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals and the ARVO Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research, under a protocol approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Doheny Eye Institute, University of Southern California. All efforts were made to minimize animal suffering and to use only the minimum number of animals necessary to provide an adequate sample size for statistically meaningful scientific conclusions. Twenty-nine transgenic pigmented S334ter-line-3 retinal degenerate rats expressing a mutated human rhodopsin protein (Sagdullaev, et al., 2003) were light-damaged for 5–6 days with blue light (Seiler et al 2000) to accelerate photoreceptor degeneration, starting at postnatal day (P) 22–26, and then received retinal sheet transplants in one eye shortly afterwards at the age of P24 to 37.

Most of the procedures used in these experiments have been described in detail elsewhere (Sagdullaev, et al., 2003; Thomas, et al., 2004a; Woch, et al., 2001) and will be briefly described.

BDNF microspheres

BDNF microspheres (average diameter 1 ± 0.5 μm) were prepared using a previously described methodology (Mahoney and Saltzman, 2001). Briefly, 300 mg of (50:50) PLGA (Mn = 54,100 Birmingham Polymers) was dissolved in 2 ml of methylene chloride. 100 μL of a solution containing 500 μg BDNF was added to the dissolved PLGA on ice. The solution was sonicated for 10 sec at 40% amplitude to yield a homogeneous mixture. 4 mL of aqueous 1% polyvinyl alcohol (PVA, Mw = 25,000, Polysciences) was added to this emulsion and vortexed for 10 seconds. This double-emulsion was poured into a beaker with 100 ml of aqueous 0.3% PVA and stirred for 3 hours to achieve microsphere formation. Microspheres were collected by centrifugation at 2000 rpm for 10 min and washed three times with deionized water before they were frozen in liquid nitrogen and then lyophilized for 24 hr. Microspheres were stored at 4°C until use. The BDNF release rate (based on 1 mg microparticles) is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Release rate of BDNF, based on 1 mg of nanoparticles, containing 1.66 μg of BDNF.

Immediately before transplantation, a suspension of 5 mg BDNF microspheres (corresponding to 8.3 μg BDNF) was incubated for one hour in 10μg/ml poly-DL-lysine in PBS to give the microspheres a positive charge to enhance tissue adherence. After washing 3 times with Hibernate E medium (BrainBits, Springfield, IL) with B-27 supplements (Gibco BRL, Baltimore MD), the microspheres were resuspended in Hibernate E medium at a concentration of 5 mg microspheres/mL (8.3 μg BDNF/mL).

Donor tissue

Transgenic rats carrying the human placental alkaline phosphatase gene (hPAP) (Kisseberth, et al., 1999) were used as the source of donor tissue for these studies. At day 19 of gestation (day of conception = day 0), fetuses were removed by Cesarean section. A small piece of the fetuses’ tails or limbs were tested by histochemistry for hPAP (Kisseberth, et al., 1999) to identify transgenic fetuses. Embryos were stored in Hibernate E medium with B-27 supplements for up to 6 hrs. Hibernate E medium is specially formulated to maintain embryonic tissue alive when refrigerated without oxygen or CO2. The retinal tissue was flattened in a drop of medium. For BDNF microsphere treatment, a drop of a freshly prepared BDNF microsphere solution (50 μL, corresponding to 41.5 ng BDNF) was added to the retinal tissue which was then incubated for at least 2 hours on ice with gentle agitation to attach the microspheres to the donor tissue. Retinal progenitor sheets were cut into rectangular pieces of 1–1.5 × 0.6 mm to fit into the previously described custom-made implantation tool (Aramant and Seiler, 2002; Seiler and Aramant, 1998). Immediately before implantation, the tissue was taken up in the correct orientation (ganglion cell side up) into the flat nozzle of the implantation tool. The orientation of the donor tissue could easily be observed in the dissection microscope. It was difficult to estimate the total volume of microspheres (i.e. the concentration of BDNF) that attached to the donor tissue, but it was in any case less than 0.5 μL of the microsphere solution (i.e. less than 8 ng BDNF).

Transplant Recipients

Transgenic pigmented S334ter-line 3 rhodopsin mutant rats were used (age at surgery 24-37d). The rats were originally produced by Xenogen Biosciences (formerly Chrysalis DNX Transgenic Sciences, Princeton, NJ), and developed and supplied with the support of the National Eye Institute by Dr. Matthew LaVail, University of California San Francisco (http://www.ucsfeye.net/mlavailRDratmodels.shtml). Recipients were the F1 generation of a cross between albino homozygous S334ter-line 3 and pigmented Copenhagen rats (Harlan, Indianapolis, IN).

Ten rats received transplants coated with BDNF microspheres, and 7 rats received transplants without microsphere coating. Six rats received injections of BDNF microspheres only (ca. 1 μL = 8.3 ng BDNF). Six age-matched rats without surgery were tested as negative controls.

Transplantation procedure

The transplantation procedure was performed according to previously described methods (Aramant and Seiler, 2002). Rats were anaesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of ketamine/xylazine (37.5 mg/kg ketamine and 5mg/kg xylazine). A small incision (0.5 – 1mm) was made just posterior to the pars plana, parallel to the limbus. The implantation instrument was inserted with extreme care to minimize disturbance of the host RPE. The graft was released into the subretinal space posteriorly near the optic disc. Transplants were placed into only one eye, leaving the other eye as a control. The incision was closed with 10-0 sutures and the eyes were treated with gentamycin eyedrops and artificial tears. The rats were placed in an incubator for recovery.

Optokinetic testing

The testing apparatus (Thomas, et al., 2004b) consisted of interchangeable circular drums with black and white stripes rotating at a velocity of 2 turns/minute around a stationary holder in which the rat sits unrestrained. Rats were tested at a spatial frequency of 0.25 cycles/degree (medium stripes). Three light sources were used to evenly illuminate one half of the drum. The optokinetic testing was done under photopic light conditions. The other half of the drum was concealed from the rat by positioning a stationary black wall to block the light path. The rat holder was positioned in the apparatus to expose only one eye to the rotating stripes, thereby permitting unilateral optokinetic testing. Each rat was tested for 4 minutes during one session, 2 minutes for each eye: one minute in one direction of drum rotation and one minute in the other direction. Videotapes of the rat’s head movements were subsequently analyzed. The amount of time the rat spent head tracking was calculated separately for each eye in a masked fashion (the examiner was not aware if the animal was a transplanted or control animal). Rats were tested at 5, 8 and 11 weeks of age.

Electrophysiology

Electrophysiological recordings were made in the SC of transgenic rats with retinal transplants (n=17), non-surgery transgenic controls (n=6) or normal pigmented rats (n=4) from 11–14 weeks of age, ca. 60 days post-surgery. For electrophysiological assessment of visual responses in the SC (Thomas, et al., 2004a), rats were dark-adapted overnight and then the eyes were covered with a custom-made eye cap. After ketamine/xylazine anesthesia (see above), the gas inhalant anesthetic (1.0–2.0% halothane in 40% O2/60% N2O) was administered via an anesthetic mask (Stoelting Company, Wood Dale, IL). Rats were mounted in a stereotaxic apparatus, a craniotomy was performed and the SC was exposed. Multi-unit visual responses were recorded extracellularly from the superficial laminae of the SC using nail polish-coated custom-made tungsten microelectrodes. Recording sites (200–400μm apart) covered the full extent of the SC with the exception of its medial area, which was located just under the superior sagittal sinus. At each recording location, up to 16 presentations of a full-field strobe flash (1.0 to 1300 cd/m2, Grass model PS 33 Photic stimulator, W. Warwick, RI), positioned 30 cm in front of the rat’s eye, were delivered to the contralateral eye. The luminance level of the flash was controlled using neutral density filters. An interstimulus interval of 6 seconds was used. All electrical activity was recorded using a digital data acquisition system (Powerlab; ADI Instruments, Mountain View, CA) 100 ms before and 500 ms after the onset of the stimulus and all responses at each site were averaged. Blank trials, in which the illumination of the eye was blocked with an opaque filter, were also recorded at each site.

The following characteristics of visual responses were analyzed: (1) Response onset latency - defined as the point at which a clear, prolonged (>20 ms) increase in the light evoked activity could be measured above background (which was determined using the 100 ms of activity preceding the light flash) and (2) Peak response amplitude- defined as the largest excursion peak to peak in the averaged response.

Histology

At the end of the recording session, animals were euthanized with an overdose of halothane, eyes were immersion fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1M Na-phosphate buffer for 2–4 hours and washed 3 times with 0.1 M Na-phosphate buffer. Dissected eye cups, oriented along the dorso-ventral axis, were infiltrated with 30% sucrose overnight, and frozen in Tissue Tek on dry ice. Transverse sections of the retina were cut at 10 μm thickness on a cryostat and mounted on to slides. Every 5th slide was stained by histochemistry for hPAP (Kisseberth, et al., 1999; Mujtaba, et al., 2002). A series of sections through the full extent of each transplant were evaluated at the light microscopic level by immunohistochemistry for various markers (see below).

Frozen sections were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and blocked for at least 30 minutes in 20% goat serum. Sections were incubated in primary antibodies overnight at 4°C, followed by 5 PBS washes. The binding of the primary antibody was detected using a 1:100 dilution of AF546 anti rabbit IgG, or a combination of AF488-anti-rabbit IgG and Rhodamine-X anti mouse-IgG, respectively (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR), and coverslipped with DAPI (4′6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole hydrochloride) -containing Vectashield mounting medium (Vector Labs). The following primary antibodies were used: rabbit antiserum against recoverin (gifts of Alexander Dizhoor (Dizhoor, et al., 1991) and McGinnis (McGinnis, et al., 1997); dilution 1:500); rabbit antiserum against red-green opsin (Chemicon, Temecula CA, dilution of 1:2,000), or a rabbit antiserum again the metabotropic glutamate receptor mGluR6 (Neuromics, Minneapolis MN, 1:200) in combination with various mouse monoclonal antibodies: antibody against human placental alkaline phosphatase (hPAP) (Chemicon, clone MAB102; 1:200); antibody against post-synaptic density protein PSD-95 (Ghosh, et al., 2001) (Stressgen, Victoria BC, Canada; 1:500), protein kinase C (PKC) (Biodesign, Saco, ME; 1:100), or rhodopsin (rho1D4, 1:50(Molday, 1983)]).

Of the three sections on a slide, one section was always double-stained with the antibody against hPAP in combination with one of the above mentioned rabbit antisera, and the other two sections with other combinations. Sections were imaged using a Zeiss LSM510 confocal microscope. Five to seven confocal slices were combined in a projection image.

Immunoreactivity for red-green opsin was used to identify the residual cone photoreceptors in the host retina as well as cone photoreceptors in the transplant in selected experiments. Red-green cones of the host retina of 6 transplant experiments without BDNF, 7 transplant experiments with BDNF, and of 4 of the 6 BDNF-only treated rats, were counted by 2–3 observers (2 independent counts), and the results expressed as cones/100 μm. Confocal images were magnified as much as possible on a computer monitor for counting purposes. The observers were masked during counting. The counts from different observers were averaged to one value. Because of the varying orientation of the transplant photoreceptors (laminated areas versus rosettes), cones in the transplants were not counted.

Statistics

Statistical comparisons were made using the Fisher exact probability test and a one way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with subsequent post hoc tests, using a statistics package of GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA. The varying N of different experimental groups was taken into account.

Results

Optokinetic testing

Transplantation of BDNF coated retinal progenitor sheets significantly improved the optokinetic head tracking behavior in the transplanted eye (p<0.05, Fig. 2), compared with transplants that were not coated with BDNF. The effect of transplantation persisted throughout the testing period (up to 11 weeks following transplantation). Although some initial improvement in the head-tracking behavior was observed in the BDNF control group (treated with BDNF microspheres only), the effect of the treatment was attenuated when animals were tested at a later age (4 weeks and 7 weeks after transplantation, Fig. 2C).

Figure 2. Optokinetic head tracking: Comparison between treated and non-treated control eyes.

A) Transplant only (n=7); B) Transplant with BDNF (n=10); C) BDNF only (n=6). BDNF treated transplanted rats exhibited a significant increase in optokinetic head tracking (spatial frequency 0.25 cycles/degree). With progression of age (tests at 5, 8 and 11 weeks), the rats with BDNF-treated transplants show an increasing and statistically significant difference between the transplanted and non-transplanted eye.

SC recording

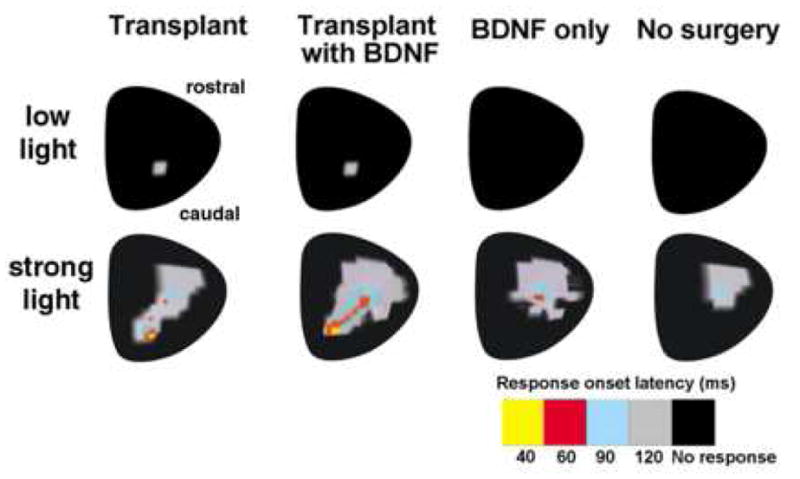

Electrophysiological evaluation of the visual responses from the SC revealed that in 80% (8/10) of the rats that received BNDF-coated transplants (Fig. 3A), visual responses could be recorded with stimulation at low light levels (1 cd/m2). In the non-BDNF transplant group, only 57 % of the rats (4/7) showed visual sensitivity to such low level light stimulation, and none of the control rats (treated with BDNF microspheres alone, n=6) showed this effect.

Figure 3. Superior colliculus recording.

A) Percentage of animals responding to low light. Responses to low light (1 cd/m2) were only found in the transplanted groups. BDNF treatment increased the percentage of transplants responding to low light. BDNF-only treatment without transplant gave no response. B) Schematic representation of response latencies in the superior colliculus to low and bright light in different experimental groups. At low light (1 cd/m2), responses are only found in transplanted rats in an area of the superior colliculus corresponding to the placement of the transplant in the host retina. BDNF treated transplants and BDNF-only treated controls show increased responses to strong light (1300 cd/m2) in the superior colliculus, with a shorter latency. Note that the responses in transplanted rats are found in an additional area of the SC, not seen with BDNF only.

The area with visual restoration in the SC corresponded to the area of the placement of the graft under the host retina (Fig. 3B).

Rats that received BDNF microspheres (BDNF alone as well as BDNF coated transplants) showed visual response to bright light stimulation (1300 cd/m2) in a large SC area (Fig. 3B) suggesting a more global effect caused by the BDNF treatment. However, responses from transplanted rats covered a larger additional area where no responses were found in BDNF-only rats. BDNF-only and non surgery rats showed no responses with low intensity light (Fig. 3B). Detailed evaluation of the characteristics of the SC visual responses further elucidated the effect of BDNF in improving the functional efficacy of the fetal retinal sheet transplants (Table 1). When comparing responses to bright light in the SC area corresponding to the location of the transplant in the host retina, the response onset latency was considerably shorter among rats that received BDNF-coated transplants (p<0.005 vs. transplant only group) when tested with bright light. A quantitative comparison of the peak response amplitude did not reveal any significant difference between the various treatment groups.

Table 1.

Visual responses to bright light (1300 cd/m2) recorded from SC.

| Groups | No. of animals used (n) | Response onset latency (RL) | Peak response amplitude (RA) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal pigmented rat (control) | 4 | 37.2±7.0 | 89.5±3.2 |

| Transgenic (RD control) | 6 | No Response | No Response |

| BDNF only | 6 | No Response | No Response |

| Transplant only | 7 | 68.4±8.9 | 51.57±3.69 |

| Transplant+BDNF | 10 | 41.9±2.8 | 64.8±4.55 |

Recordings were made from an area of the SC that corresponds to the area where the transplants are generally placed inside the eye. Transplants treated with BDNF microspheres had a shorter response onset latency than untreated transplants (p<0.005, Transplant + BDNF vs Transplant only). See also Figure 2.

Histological evaluation

Transplant organization was variable within both groups (see Table 2). Several transplants contained laminated areas with photoreceptor outer segments contacting host RPE in the center. All transplants also contained areas with rosettes (photoreceptors with inner and outer segments arranged in spheres), and some transplants were composed mostly of disorganized areas. There was no apparent correlation between transplant organization and BDNF treatment as evidenced by recoverin staining of photoreceptors and cone bipolar cells in transplants and host retina (data not shown).

Table 2.

Overview of histological organization of transplants

| Experimental group | N | Laminated areas + rosettes | Rosettes only | Rosettes + disorganized |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transplants | 7 | 3 | 4 | - |

| good response in SC to low light | 4 | 1 | 3 | - |

| no or weak response to low light | 3 | 2 | 1 | - |

| Transplants with BDNF | 10 | 2 | 6 | 2 |

| good response in SC to low light | 8 | 2 | 5 | 1 |

| no or weak response to low light | 2 | - | 1 | 1 |

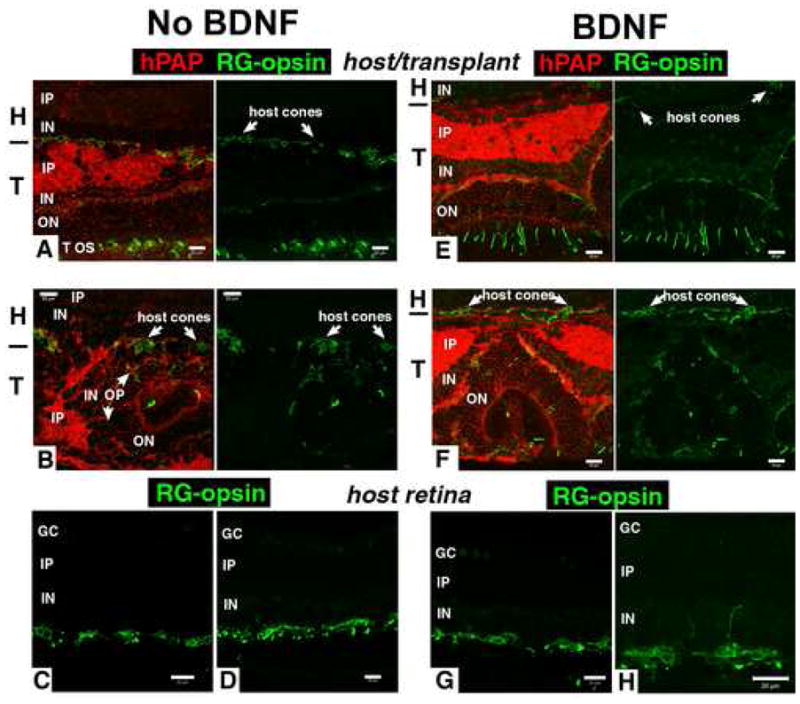

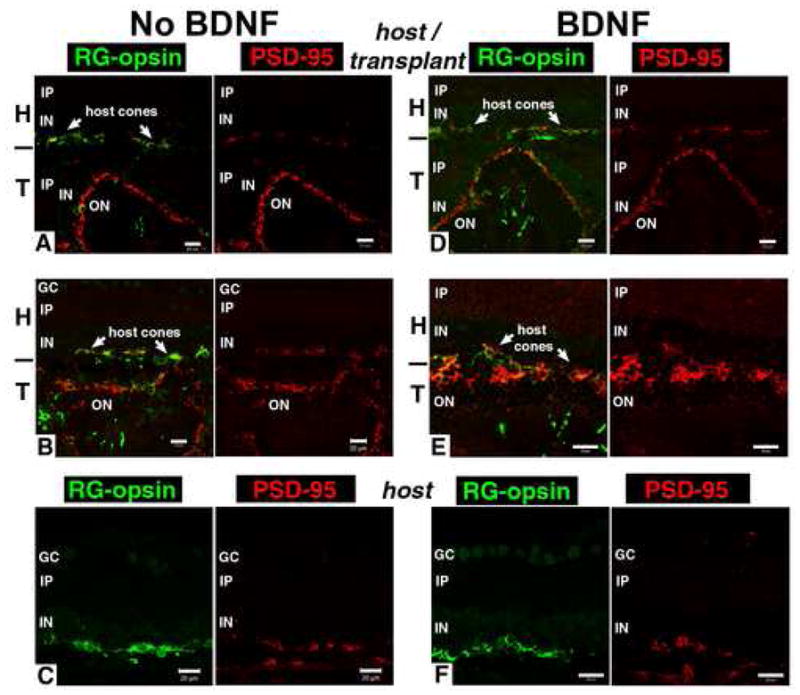

In contrast to red-green opsin immunoreactivity in the normal retina which was concentrated in the outer segments (Fig. 4A), cones in the degenerate S334-ter line 3 retinas showed immunoreactivity in the cell soma, cell processes, and sometimes in very short outer segments (Figs. 4B, 5C, D, G, H; 6C, F). In well-laminated areas, transplant cones showed normal red-green opsin immunoreactivity (mainly in the cone outer segments) (see Fig. 5A, E, 6A, D), whereas abnormal staining of cone somas was seen in more disorganized areas (Figs. 5BF; 6 B, E). PSD-95 staining was much stronger and often almost normal in the outer plexiform layers of the transplants even when the photoreceptors were arranged in rosettes (see Fig. 6) whereas PSD-95 immunoreactivity was patchy in the host retina independent of the presence of a transplant. In normal retina, mGluR6 immunoreactivity was seen as punctate staining in the outer plexiform layer (Fig. 7A). The immunostaining pattern for mGluR6 was abnormal in degenerated retinas, independent of the presence of a transplant or BDNF treatment (Figs 7B, C; Fig. 8).

Figure 4. Comparison between normal and retinal degenerate transgenic retina: Red-green opsin and rhodopsin immunoreactivity.

A) Normal retina. Red-green opsin (RG opsin) (green) and rhodopsin (rho1D4) (red) immunoreactivity in outer segments of cones and rods, respectively. B) Transgenic S334ter line-3 retina, age 35 days, 5 days light damage (postnatal day 23 to 28). Cell bodies and processes of residual photoreceptors stained with RG-opsin and rhodopsin. No rhodopsin immunoreactivity was seen in older S334ter line-3 rats (data not shown). Bars = 20 μm.

Figure 5. Red-green opsin immunoreactivity: Host cones variable and abnormal, laminated transplant areas normal.

This figure shows that the number of host cones overlying the transplants is variable, and sometimes reduced (see results of counts in Figure 8), that the immunoreactivity of host cones is abnormal, and that transplants have normal cone opsin immunoreactivity in cone outer segments in laminated areas. Figures A, B, E, F show double staining for RG-opsin (green) and the transplant label human alkaline phosphatase (red) on the left, and single RG-opsin staining of the same field on the right. Figures C, D, G, H, show only RG-opsin staining.

A) Transplant without BDNF, age 91 days, 60 days post-surgery. Normal RG cone-opsin distribution in transplant cones. Abnormal cone opsin in the overlaying host retina.

B) Transplant without BDNF, age 90 days, 58 days post-surgery. Abnormal RG cone-opsin immunoreactivity in the cell somas of host cones. The transplant contains a photoreceptor rosette on the right with few cone outer segments.

C), D) Representative RG cone opsin staining of central ventral host retina of two different transplant experiments (C):age 96 days, D): age 83 days). RG-opsin staining of cone cell somas, processes, and few short outer segments.

E) Transplant with BDNF, age 78 days, 54 days post surgery. Normal immunoreactivity in transplant, almost no cone opsin in host.

F) Different area of transplant in E). Cell processes of cones in overlying host retina immunoreactive for RG-opsin. Staining of some outer segments in transplant rosette.

G) H) Representative RG cone opsin staining of central ventral host retina of two different transplant experiments with BDNF treatment (G): age 91 days, H): age 78 days). Note the abnormal sprouting of a cone process into the inner plexiform layer in H). Bars = 20 μm.

Figure 6. Strong PSD-95 staining in outer plexiform layer of transplant, reduced in host.

All figures show double staining for RG-opsin (green) and post-synaptic marker PSD-95 (marker for bipolar cell synapses with photoreceptors) (red) on the left, and single PSD-95 staining (red) of the same field on the right. The area of the transplant was determined by hPAP staining of adjacent sections (see Figure 5).

A) Transplant without BDNF, age 96 days, 65 days post surgery. Intense PSD-95 staining of outer plexiform layer of laminated transplant. Only patchy PSD-95 staining in overlying host retina. B) Another area of the same transplant. Outer plexiform layer in rosettes shows intense PSD95 staining. Only patchy PSD95 in host close to terminals of remaining cones. C) Central ventral host retina of same experiment. Only patchy PSD-95 staining close to terminals of remaining cones.

D), E) Transplants with BDNF treatment. Strong PSD-95 staining of outer plexiform layer of transplant rosettes. Abnormal RG-opsin in host cones while the transplant exhibits more normal outer segment staining. D) Same transplant as in Figure 5E). E) Different transplant, age 93 d (63 days post-surgery). F) Central host retina of BDNF-treated transplant, age 79 days (42 days post-surgery), similar in appearance to non-BDNF treated host retina with patchy PSD-95 (C). Bars = 20 μm.

Figure 7. Comparison between normal and retinal degenerate transgenic host retina.

mGluR6 (marker for bipolar cell synaptic dendrites) in combination with protein kinase C (PKC; marker for rod bipolar cells). Enlargements of the outer plexiform layer staining are shown in white framed insets. A) Normal retina. mGluR6 (green) stains small spots in the outer plexiform layer where rod bipolar cells stained by PKC (red) receive synaptic input from rods. B) Central ventral S334ter line-3 host retina outside transplant without BDNF treatment, age 91 days (same animal as in Figure 5A). mGluR6 has an abnormal staining pattern of bipolar cell processes and cell bodies verified by double staining with PKC. C) Central ventral S334ter line-3 host retina of BDNF-treated transplant, age 78 days (same animals as in Figure 5E). Abnormal distribution of mGluR6 (similar to B). Bars = 20 μm.

Figure 8. Near normal bipolar cells in transplant, but abnormal in host.

mGluR6 in combination with protein kinase C. Enlargements of the outer plexiform layer staining are shown in white framed insets. The approximate border between transplant and host is indicated by a black line on the side. The area of the transplant was determined by hPAP staining of adjacent sections (see Figure 5).

A) Transplant without BDNF, age 89 days (57 days post-surgery). Laminated transplant area. The bipolar cells receiving input from transplant rods show close to normal small spot mGluR6 staining in the outer plexiform layer of the transplant. Abnormal interactions between host bipolar cells and host cones indicated by irregular staining of cell bodies and processes of bipolar cells with mGluR6. B) Rosetted area of transplant without BDNF (same transplant as in Figs. 5A; 6A, B).

C), D) Transplants with BDNF treatment. Normal punctate staining of mGluR6 in transplant OPL, abnormal staining in host retina. Strong PKC immunoreactivity of transplant bipolar cell terminals and of cone outer segments. C). Laminated transplant area (same transplant as in Figs. 5D, E; 6D). D) Transplant with BDNF treatment, age 79 days (42 days post-surgery). Bars = 20 μm.

Cone counts of red-green opsin immunoreactive cones showed a significant reduction of cones in the host retina over the transplant versus the rest of the host retina in the BDNF-treated groups (Figure 9). Although there were fewer host cones in the transplant area in the non-treated transplant group, this difference was not significant. Both BDNF treated and non-treated transplant areas contained significantly less host cones than the BDNF-only treated retinas. The cones in the transplant could not be counted reliably because of difficulties presented by their varying orientation within rosettes. There was no significant difference in the number of cones between the corresponding retinal locations of BDNF-treated and no treatment control eyes.

Figure 9. Quantification of host cones.

This figure implicates that visual responses are independent of the density of host cones. Red-green opsin immunoreactive host cones were counted in the transplant area, and host central and peripheral retina outside the transplant. Counts were done on enlarged images. A) transplanted eyes without BDNF treatment, B) transplanted eyes with BDNF treatment, and C) eyes with injection of BDNF microspheres only. N indicates the number of images evaluated. Values shown are mean ± S.E.M cones per 100 μm. In the BDNF treated groups, significantly less host cones were found in the transplant area than in the surrounding host retina (p< 0.001 BDNF treated transplant area vs. BDNF treated central host retina; p<0.01 BDNF treated transplant areas vs. BDNF treated peripheral host retina). Less host cones were also found in the transplant area in the non-treated group vs. the host retina outside the transplant. This difference was not significant, however. Both BDNF treated and non-treated transplant areas contained significantly less host cones than the BDNF-only treated retinas. The cones in the transplant were not counted. There was no significant difference between BDNF treatment and non-treatment in the corresponding locations.

Discussion

This study demonstrates that treatment with BDNF microspheres enhances the functional efficacy of retinal progenitor sheet transplants in S334ter-line3 rats. This is evidenced by visual head-tracking behavior as well as recording of visual responses in the brain (SC) by electrophysiology.

In a previous study (Thomas, et al., 2004b), it was shown that retinal transplants (without BDNF) delay the deterioration of optokinetic responses to large stripes (0.125 cycles/degree). In the current study, more narrow stripes were used (0.25 cycles/degree). - When the transplants were coated with BDNF microspheres, head-tracking behavior of the transplanted eye was consistently better. Although BDNF treated control rats (without transplants) also showed some initial improvement in the head-tracking behavior, this effect was not apparent when tested at a later age, suggesting that the initial visual improvement observed in the BDNF control group (BDNF microspheres only) may be due to a temporary delay in the progression of the disease. In contrast, the more persistent improvement in visual head tracking behavior observed in rats that received BDNF coated transplants suggests that the transplanted cells contributed to the increased function. Alternatively, if combining BDNF spheres with the transplant results in prolonged activity of the biological effect of BDNF (e.g., via decreased clearance rate of the microspheres from the eye), then one way to interpret Figures 2B and C is that the restoration of head tracking is due to BDNF and not the transplant.

Functional improvement following BDNF-coated retinal sheet transplantation was further demonstrated by electrophysiological recording from the SC. Previous electrophysiology data obtained from 3 different retinal degenerate rat models demonstrated that retinal transplantation has a restorative effect even at many months after transplantation, as recorded in the SC (Sagdullaev, et al., 2003; Thomas, et al., 2004a; Woch, et al., 2001). Since visual responses in these prior studies were evaluated using a very intense light stimulus (1300 cd/m2), the possible contributions from the transplanted photoreceptors (primarily rods) could not be distinguished from responses derived from the residual host cones. It is important to note that in S334ter-line3 rats at the time of transplantation (24–37 days of age), most of the host rod photoreceptors are degenerated, leaving only a few cones and rare surviving rods (Sagdullaev, et al., 2003) (Figure 4B). No rods can be detected by immunohistochemistry for rhodopsin at an age of 50 days or later (unpublished data). The only rods in the eye present at the time of SC recording (72–97 days) are localized in the transplant as evidenced by histological examination (unpublished data). Thus, the present study is different in design from other studies that are looking at photoreceptor rescue since in this study most photoreceptors have degenerated at the time of transplantation. For example, McGee-Sanftner and co-workers showed that GDNF overexpression rescued photoreceptors both morphologically and functionally - as determined by ERG - in the S334ter line 4 rat model (McGee Sanftner, et al., 2001) which has a slower time course of retinal degeneration than the S334ter line 3 rat used in the current study. In the present investigation, low intensity mesopic light (1 cd/m2) (which stimulates both rods and cones) was used to record the visual contribution from the transplanted rods in addition to cones. BDNF treatment increased the percentage of transplanted rats responding to this low level of light. The location of the visual responses to low light in the SC was restricted to an area corresponding to the position of the graft. This suggests that the photoreceptors of the transplant contributed to the light sensitivity. No improvement in the visual sensitivity to low light was observed when BDNF treatment alone was administered (without any graft).

When a strong light stimulus was used (1300 cd/m2), a comparatively large SC area showed robust visual activity from both groups of BDNF treated rats (BDNF-only and transplant with BDNF). However, in the BDNF-treated transplanted rats, this highly responsive area included the SC area corresponding to the placement of the graft in the eye, whereas, in the BDNF-only treated group, the improvement was mainly localized to the SC area where some residual visual activity could be detected even in non-treated control S334ter-line3 rats. The restored visual activity in the SC of the BDNF treated transplant group was characterized by a shorter response onset latency. One possible mechanism responsible for this shorter onset latency could be a beneficial effect on host cones by the BDNF. The visual electrical output from the retina may be higher in the presence of a large number of surviving cones, and this higher output may enhance the transmission speed of the visual signals, thus shortening the response onset latency. A relatively normal response onset latency was correlated with photoreceptor rescue by RPE transplants in the Royal College of Surgeons (RCS) rat (Sauve, et al., 2002). In addition, BDNF may have an effect on the inner host retina (Harada, et al., 2005; Pinzon-Duarte, et al., 2004; Thanos and Emerich, 2005). Although previous retinal progenitor sheet transplantation studies (without BDNF coating) demonstrated some improvement in the response latency (Sagdullaev, et al., 2003; Thomas, et al., 2004a; Woch, et al., 2001), the present investigation of BDNF-treated transplants demonstrates a much faster response latency, approaching that of normal (non-transgenic) rats.

Using ganglion cell recordings and pupillary responses, MacLaren et al. concluded that transplants of retinal progenitor cells caused visual improvement in different mouse models (MacLaren, et al., 2006). Previous studies have demonstrated restoration of pupillary responses (Silverman, et al., 1992) and ganglion cell responses (Radner, et al., 2002) due to retinal transplants, but the reliability of these testing methods to show visual improvement has been questioned (An, et al., 2002; Kovalevsky, et al., 1995).

However, if host cone rescue was the sole reason for this effect, one should also expect a corresponding increase in the peak response amplitude, which was not apparent in any of the experimental groups. Also, in the BDNF-only treated group, no rescue effect was apparent in the area of the SC corresponding to the transplant area of the eye. This suggests that cone rescue cannot explain the visual improvement observed in the BDNF coated transplant group. The underlying mechanism may involve not only BDNF, but other factors related to the transplanted cells. Indeed, our cone counts showed that the transplants did not rescue host cones – fewer host cones were found in the transplant area than in the rest of the host retina whereas numerous rod and cone photoreceptors could be found in the transplants.

Various physiological and biochemical processes may be involved in this BDNF induced visual restorative mechanism. It is well documented that progressive changes take place in the retinal neural circuitry following the degeneration of the photoreceptors (Jones and Marc, 2005; Marc, et al., 2003; Strettoi, et al., 2004). The immunohistochemical studies of the bipolar synaptic markers mGluR6 and PSD-95 was consistent with abnormal rewiring of the inner host retina after photoreceptor loss. These markers were chosen because of their abnormal distribution shown in other retinal degeneration models (Blackmon, et al., 2000; Cuenca, et al., 2004; Cuenca, et al., 2005; Peng, et al., 2003). There was no apparent effect of the transplant or of BDNF treatment on the abnormal distribution of these markers in the host retina of rats with visual responses. An important finding was that the distribution of these synaptic markers was almost normal in laminated areas of the transplant. Some of these anomalies that occurred in the host neural circuitry may influence the normal propagation of the retinal neural signals, resulting in a longer response onset latency that has been reported among different retinal degenerative rat models (Sagdullaev, et al., 2003; Thomas, et al., 2004a; Woch, et al., 2001). The present study demonstrates that a more or less normal response latency level could be restored by transplantation with retinal progenitor sheets coated with BDNF microspheres. Treatment with BDNF alone (without a graft) had no effect on the response latency which suggests that BDNF acts synergistically with other ‘factors’ released by the transplanted tissue. This combined effect may result in some restoration of the disturbed neural circuitry of the degenerating host retina which is supported by data from other investigators demonstrating neuro-protective effects of BDNF (Chaum, 2003; Ikeda, et al., 2003; Keegan, et al., 2003; Lawrence, et al., 2004; Nakazawa, et al., 2002; Paskowitz, et al., 2004).

A major limitation in most retinal transplantation studies is the unknown level of functional integration between the transplant and the host retina, despite recent trans-synaptic tracing studies demonstrating synaptic connections at the host-transplant interface (Seiler, et al., 2005). Deficits in the functional integration could be one among many factors responsible for a limited level of visual restoration in transplanted rats (Sagdullaev, et al., 2003; Thomas, et al., 2004a; Woch, et al., 2001).

Although various techniques have been performed to promote the neuronal integration between the transplant and the host retina (Kinouchi, et al., 2003; Lavik, et al., 2005), no clear evidence of functional synaptic connectivity has yet been published. However, preliminary data from our group have shown that neurons in the transplant can be trans-synaptically labeled from the visually responsive site in the SC (Seiler et al., 2005, IOVS, 45: ARVO E-abstract 4164; manuscript submitted). The visual improvement described in the present study may also be due to an improvement in the quality of neuronal connections established between the transplant and the host retina.

It is remarkable that only a low BDNF dose during a very short term period markedly enhances tissue transplantation efficacy. A maximum of 8 ng BDNF was administered into the subretinal space and around 2000-fold less BDNF was measured 24 hours after an in vitro incubation test. The maximum volume that can be injected reliably into the subretinal space is about 3 μL (Dureau, et al., 2000); thus, the total volume of the subretinal space is likely only about 5 μL. However, the microspheres and the transplant were confined to a small area (about 1 mm2) so the local concentration of BDNF could be much higher.

In summary, BDNF enhanced the functional efficacy of the retinal progenitor sheet transplants as evidenced by behavioral and electrophysiology data. The effect was not significant with BDNF treatment alone (without transplants) suggesting a synergistic effect between BDNF and the graft. BDNF may have acted in conjunction with other ‘factors’ released from the transplanted cells and helped to restore some of the retinal environment and circuitry, thereby accounting for the apparent normalization of the response latency. Given the enhancement in responsiveness to low light stimulation, BDNF may have also promoted neuronal connections between the transplant and the host retina which still requires further study.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Laurie LaBree (University of Southern California) for statistical consultation; Guanting Qiu for poly-lysine coating of microspheres; Xiaoju Xu and Rongjuan Wu for technical assistance and Christine Winarko for counting red-green cones. This work was supported by: The Foundation Fighting Blindness, Foundation for Retinal Research, Michael Panitch Fund for Retinal Research, NIH EY03040, NIH EY054375 and private funds.

List of Abbreviations in Text and Figures

- BDNF

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor

- DAPI

4′6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole hydrochloride

- CNS

central nervous system

- GC

ganglion cell layer

- H

host retina

- hPAP

human placental alkaline phosphatase

- IN

inner nuclear layer

- IP

inner plexiform layer

- mGluR6

metabotropic glutamate receptor 6 (synaptic receptor on bipolar cells)

- ms

milliseconds

- ON

outer nuclear layer

- OP

outer plexiform layer

- OS

outer segments

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- PKC

protein kinase C (marker for rod bipolar cells)

- PLGA

Poly-lactide-co-glycolide

- PSD-95

post-synaptic density protein 95 (post-synaptic marker on bipolar cell dendrites)

- RG-opsin

red-green opsin

- RPC

retinal progenitor cells

- SC

superior colliculus

- RCS

Royal College of Surgeons

- RPE

retinal pigment epithelium

- T

transplant

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

MJS and RBA have a proprietary interest in the implantation instrument and method.

References

- An GJ, Asayama N, Humayun MS, Weiland J, Cao J, Kim SY, Grebe R, de Juan E, Jr, Sadda S. Ganglion cell responses to retinal light stimulation in the absence of photoreceptor outer segments from retinal degenerate rodents. Curr Eye Res. 2002;24:26–32. doi: 10.1076/ceyr.24.1.26.5432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arai S, Thomas BB, Seiler MJ, Aramant RB, Qiu G, Mui C, de Juan E, Sadda SR. Restoration of visual responses following transplantation of intact retinal sheets in rd mice. Exp Eye Res. 2004;79:331–41. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2004.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aramant RB, Seiler MJ. Retinal transplantation--advantages of intact fetal sheets. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2002;21:57–73. doi: 10.1016/s1350-9462(01)00020-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aramant RB, Seiler MJ. Progress in retinal sheet transplantation. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2004;23:475–94. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2004.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berardi N, Maffei L. Neurotrophins, Electrical activity, and the development of visual function. In: Chalupa LM, Werner JS, editors. The visual neurosciences. Vol. 1. The MIT press; Massachusetts: 2004. pp. 33–45. [Google Scholar]

- Blackmon SM, Peng YW, Hao Y, Moon SJ, Oliveira LB, Tatebayashi M, Petters RM, Wong F. Early loss of synaptic protein PSD-95 from rod terminals of rhodopsin P347L transgenic porcine retina. Brain Res. 2000;885:53–61. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02928-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaum E. Retinal neuroprotection by growth factors: a mechanistic perspective. J Cell Biochem. 2003;88:57–75. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuenca N, Pinilla I, Sauve Y, Lu B, Wang S, Lund RD. Regressive and reactive changes in the connectivity patterns of rod and cone pathways of P23H transgenic rat retina. Neuroscience. 2004;127:301–17. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.04.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuenca N, Pinilla I, Sauve Y, Lund R. Early changes in synaptic connectivity following progressive photoreceptor degeneration in RCS rats. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;22:1057–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delyfer MN, Leveillard T, Mohand-Said S, Hicks D, Picaud S, Sahel JA. Inherited retinal degenerations: therapeutic prospects. Biol Cell. 2004;96:261–9. doi: 10.1016/j.biolcel.2004.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dizhoor AM, Ray S, Kumar S, Niemi G, Spencer M, Brolley D, Walsh KA, Philipov PP, Hurley JB, Stryer L. Recoverin: a calcium sensitive activator of retinal rod guanylate cyclase. Science. 1991;251:915–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1672047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dureau P, Legat L, Neuner-Jehle M, Bonnel S, Pecqueur S, Abitbol M, Dufier JL. Quantitative analysis of subretinal injections in the rat. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2000;238:608–14. doi: 10.1007/s004170000156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauthier R, Joly S, Pernet V, Lachapelle P, Di Polo A. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor gene delivery to muller glia preserves structure and function of light-damaged photoreceptors. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:3383–92. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh KK, Haverkamp S, Wassle H. Glutamate receptors in the rod pathway of the mammalian retina. J Neurosci. 2001;21:8636–47. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-21-08636.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harada C, Harada T, Quah HM, Namekata K, Yoshida K, Ohno S, Tanaka K, Parada LF. Role of neurotrophin-4/5 in neural cell death during retinal development and ischemic retinal injury in vivo. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:669–73. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-0826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda K, Tanihara H, Tatsuno T, Noguchi H, Nakayama C. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor shows a protective effect and improves recovery of the ERG b-wave response in light-damage. J Neurochem. 2003;87:290–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01994.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones BW, Marc RE. Retinal remodeling during retinal degeneration. Exp Eye Res. 2005;81:123–37. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2005.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keegan DJ, Kenna P, Humphries MM, Humphries P, Flitcroft DI, Coffey PJ, Lund RD, Lawrence JM. Transplantation of syngeneic Schwann cells to the retina of the rhodopsin knockout (rho(−/−)) mouse. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:3526–32. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-0097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinouchi R, Takeda M, Yang L, Wilhelmsson U, Lundkvist A, Pekny M, Chen DF. Robust neural integration from retinal transplants in mice deficient in GFAP and vimentin. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:863–8. doi: 10.1038/nn1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kisseberth WC, Brettingen NT, Lohse JK, Sandgren EP. Ubiquitous expression of marker transgenes in mice and rats. Dev Biol. 1999;214:128–38. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovalevsky G, DiLoreto D, Jr, Wyatt J, del Cerro C, Cox C, del Cerro M. The intensity of the pupillary light reflex does not correlate with the number of retinal photoreceptor cells. Exp Neurol. 1995;133:43–9. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1995.1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwan AS, Wang S, Lund RD. Photoreceptor layer reconstruction in a rodent model of retinal degeneration. Exp Neurol. 1999;159:21–33. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1999.7157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavik EB, Klassen H, Warfvinge K, Langer R, Young MJ. Fabrication of degradable polymer scaffolds to direct the integration and differentiation of retinal progenitors. Biomaterials. 2005;26:3187–96. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence JM, Keegan DJ, Muir EM, Coffey PJ, Rogers JH, Wilby MJ, Fawcett JW, Lund RD. Transplantation of Schwann cell line clones secreting GDNF or BDNF into the retinas of dystrophic Royal College of Surgeons rats. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:267–74. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loewenstein JI, Montezuma SR, Rizzo JF., 3rd Outer retinal degeneration: an electronic retinal prosthesis as a treatment strategy. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122:587–96. doi: 10.1001/archopht.122.4.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund RD, Kwan AS, Keegan DJ, Sauve Y, Coffey PJ, Lawrence JM. Cell transplantation as a treatment for retinal disease. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2001;20:415–49. doi: 10.1016/s1350-9462(01)00003-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLaren RE, Pearson RA, MacNeil A, Douglas RH, Salt TE, Akimoto M, Swaroop A, Sowden JC, Ali RR. Retinal repair by transplantation of photoreceptor precursors. Nature. 2006;444:203–7. doi: 10.1038/nature05161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney MJ, Saltzman WM. Transplantation of brain cells assembled around a programmable synthetic microenvironment. Nat Biotechnol. 2001;19:934–9. doi: 10.1038/nbt1001-934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marc RE, Jones BW, Watt CB, Strettoi E. Neural remodeling in retinal degeneration. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2003;22:607–55. doi: 10.1016/s1350-9462(03)00039-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGee Sanftner LH, Abel H, Hauswirth WW, Flannery JG. Glial cell line derived neurotrophic factor delays photoreceptor degeneration in a transgenic rat model of retinitis pigmentosa. Mol Ther. 2001;4:622–9. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2001.0498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGinnis JF, Stepanik PL, Jariangprasert S, Lerious V. Functional significance of recoverin localization in multiple retina cell types. J Neurosci Res. 1997;50:487–95. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19971101)50:3<487::AID-JNR15>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molday RS. Monoclonal antibodies to rhodopsin and other proteins of rod outer segments. Progress in Retinal Research. 1983;8:173–209. [Google Scholar]

- Mujtaba T, Han SS, Fischer I, Sandgren EP, Rao MS. Stable expression of the alkaline phosphatase marker gene by neural cells in culture and after transplantation into the CNS using cells derived from a transgenic rat. Exp Neurol. 2002;174:48–57. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2001.7847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakazawa T, Tamai M, Mori N. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor prevents axotomized retinal ganglion cell death through MAPK and PI3K signaling pathways. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43:3319–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paskowitz DM, Nune G, Yasumura D, Yang H, Bhisitkul RB, Sharma S, Matthes MT, Zarbin MA, Lavail MM, Duncan JL. BDNF reduces the retinal toxicity of verteporfin photodynamic therapy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:4190–6. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-0676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng YW, Senda T, Hao Y, Matsuno K, Wong F. Ectopic synaptogenesis during retinal degeneration in the royal college of surgeons rat. Neuroscience. 2003;119:813–20. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00153-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinzon-Duarte G, Arango-Gonzalez B, Guenther E, Kohler K. Effects of brain-derived neurotrophic factor on cell survival, differentiation and patterning of neuronal connections and Muller glia cells in the developing retina. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;19:1475–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03252.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radner W, Sadda SR, Humayun MS, Suzuki S, de Juan E., Jr Increased spontaneous retinal ganglion cell activity in rd mice after neural retinal transplantation. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43:3053–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radtke ND, Aramant RB, Seiler MJ, Petry HM, Pidwell D. Vision change after sheet transplant of fetal retina with retinal pigment epithelium to a patient with retinitis pigmentosa. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122:1159–65. doi: 10.1001/archopht.122.8.1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagdullaev BT, Aramant RB, Seiler MJ, Woch G, McCall MA. Retinal transplantation-induced recovery of retinotectal visual function in a rodent model of retinitis pigmentosa. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:1686–95. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-0615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauve Y, Girman SV, Wang S, Keegan DJ, Lund RD. Preservation of visual responsiveness in the superior colliculus of RCS rats after retinal pigment epithelium cell transplantation. Neuroscience. 2002;114:389–401. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00271-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seiler MJ, Aramant RB. Intact sheets of fetal retina transplanted to restore damaged rat retinas. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1998;39:2121–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seiler MJ, Aramant RB, Ball SL. Photoreceptor function of retinal transplants implicated by light-dark shift of S-antigen and rod transducin. Vision Res. 1999;39:2589–96. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(98)00326-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seiler MJ, Sagdullaev BT, Woch G, Thomas BB, Aramant RB. Transsynaptic virus tracing from host brain to subretinal transplants. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;21:161–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03851.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman MS, Hughes SE, Valentino T, Liu Y. Photoreceptor transplantation: Anatomic, electrophysiologic, and behavioral evidence for the functional reconstruction of retinas lacking photoreceptors. Exp Neurol. 1992;115:87–94. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(92)90227-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strettoi E, Mears AJ, Swaroop A. Recruitment of the rod pathway by cones in the absence of rods. J Neurosci. 2004;24:7576–82. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2245-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thanos C, Emerich D. Delivery of neurotrophic factors and therapeutic proteins for retinal diseases. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2005;5:1443–52. doi: 10.1517/14712598.5.11.1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas BB, Seiler MJ, Sadda SR, Aramant RB. Superior colliculus responses to light - preserved by transplantation in a slow degeneration rat model. Exp Eye Res. 2004a;79:29–39. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2004.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas BB, Seiler MJ, Sadda SR, Coffey PJ, Aramant RB. Optokinetic test to evaluate visual acuity of each eye independently. J Neurosci Methods. 2004b;138:7–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2004.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woch G, Aramant RB, Seiler MJ, Sagdullaev BT, McCall MA. Retinal transplants restore visually evoked responses in rats with photoreceptor degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42:1669–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]