Abstract

The conformational plasticity of serpins underlies both their activities as protease inhibitors and their susceptibility to pathogenic misfolding. Here, we structurally characterize a sheet-opened state of the serpin alpha-1 antitrypsin (α1AT) and show how local unfolding allows functionally essential strand insertion. Mutations in α1AT that cause polymerization-induced serpinopathies map to the labile region, suggesting that the evolution of serpin function required them to sample conformations on a dynamic energy landscape that increased risk of aggregation.

Serine protease inhibitor (serpin) superfamily members modulate proteolytic cascades in a wide array of physiological systems1. The native inhibitory serpin fold comprises three β-sheets, termed A-C, surrounded by eight to nine α-helices, hA-hI; the exposed reactive centre loop (RCL) that links the fifth strand of the A-sheet (s5A) and strand s1C (Fig. 1a). Key to serpin protease inhibitory function is a major conformational transition triggered upon cleavage at a site within the RCL2. The released N-terminal portion of the RCL, linked by acylation to the protease, inserts into the central β-sheet, thus enlarging it from five strands to six and converting the metastable native state to a loop-inserted alternative fold complexed with a disabled target protease. Even without RCL cleavage, serpins undergo a slow conversion to a loop-inserted, non-functional ‘latent state’3,4. Topologically, the irreversible change in serpin tertiary structure involves insertion of the exposed RCL between parallel strands 3A and 5A to form the predominantly anti-parallel A-sheet (Fig. 1b) and is accompanied by a large increase in the overall protein stability5,6. A transiently opened A-sheet state is an obligatory precursor for either functional intra- or pathogenic intermolecular strand insertion. Detailed structural characterization of this sheet-opened intermediate should provide insight into serpin function and also offer potential routes to therapeutic intervention in serpinopathies7.

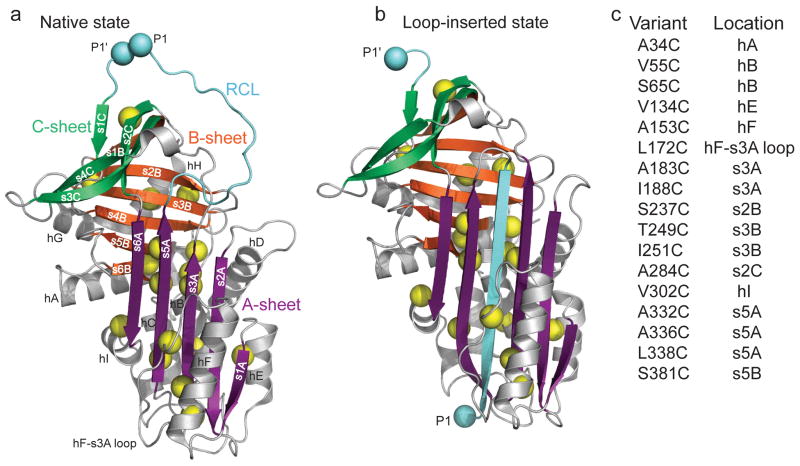

Figure 1.

Design of cysteine mutations to probe low denaturant-induced strand opening in the serpin α1AT. Comparison of structures of (a) native (PDB 1QLP)31 and (b) cleaved ‘loop-inserted’ (PDB 1EZX)2 states of α1AT. The two light blue spheres, labeled P1 and P1′, correspond to the protease cleavage site in the RCL. Sites mutated to cysteine are indicated by yellow spheres centered on the Cβ. (c) Positions of cysteine substitutions and their secondary structural context. Structures in this and other figures were prepared using PyMol (http://www.pymol.org).

In low concentrations of the denaturant guanidinium chloride (GdmCl), the serpin α1AT populates a folding intermediate that is highly polymerogenic8–11, as expected for the sheet-opened conformation. Moreover, the mechanism of polymerization for mutants of α1AT in cells and upon in-vitro treatment with GdmCl seems to be similar based on the data of Yamasaki et al.10, although antibodies raised against in vivo polymers recognize polymers formed in vitro upon heat treatment but not those formed in GdmCl11. Puzzlingly, efforts to characterize the polymerogenic state have yielded inconsistent pictures. One study concluded that the sheet-opened intermediate of α1AT possesses an intact B-sheet, destabilized A- and C-sheets12, and a highly disrupted F-helix13. Consistent with this conclusion, Wang et al. observed selective tryptic cleavage of lysine residues on strands 5 and 6 of the A-sheet of the serpin plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 in low urea6. An intermediate with an “unstructured and flexible strand s5A” was also invoked14 to explain the structure of an antithrombin dimer9. In contrast, a recent study reported that only one small region of α1AT retained any stable hydrogen bonding in the intermediate ensemble15. Additionally, the finding that random mutations introduced at widely dispersed sites could stabilize the native state of α1AT led to the suggestion that highly distributed labile regions underlie serpin conformational metastability16.

We have used thiol reactivity with a high molecular weight polyethylene glycol maleimide (PEG-Mal) reagent17 to probe changes in exposure of sites within α1AT between the native state and the sheet-opened intermediate. This method sensitively and rapidly reports on structural details, thus avoiding artifacts due to polymerization.

RESULTS

Design and validation of cysteine probe sites

We constructed single cysteine-containing variants of α1AT in the functional C232S α1AT background18, choosing sites for mutation that are sequestered, and therefore unreactive, in the native state (Fig. 1a and 1c and Supplementary Fig. 1). Positions for cysteine substitution were selected to interrogate different regular structural elements of the protein and to be tolerant of mutation based on high sequence variability at the chosen position and the presence of a cysteine, if possible, in at least one of 216 homologous sequences. Seventeen single-cysteine α1AT variants passed a qualitative activity screen in lysates (Supplementary Fig. 2) and showed near wild type stoichiometry of inhibition against trypsin assayed under steady-state conditions, indicating that there is no apparent effect of the cysteine substitutions on the native metastable structure of the protein (Supplementary Table 1). Each of these single cysteine mutants displayed a biphasic circular dichroism (CD) equilibrium denaturation curve with a stable intermediate populated near 1.5 M GdmCl19,20 and with only modest perturbation to thermodynamic parameters relative to wild type (WT) α1AT (Supplementary Table 2). The formation of the stable intermediate parallels increase in aggregation propensity21, arguing that this is indeed the polymerogenic species. Consistent with this conclusion was our observation that the second transition in GdmCl CD titrations was fully reversible, but the first was not (data not shown).

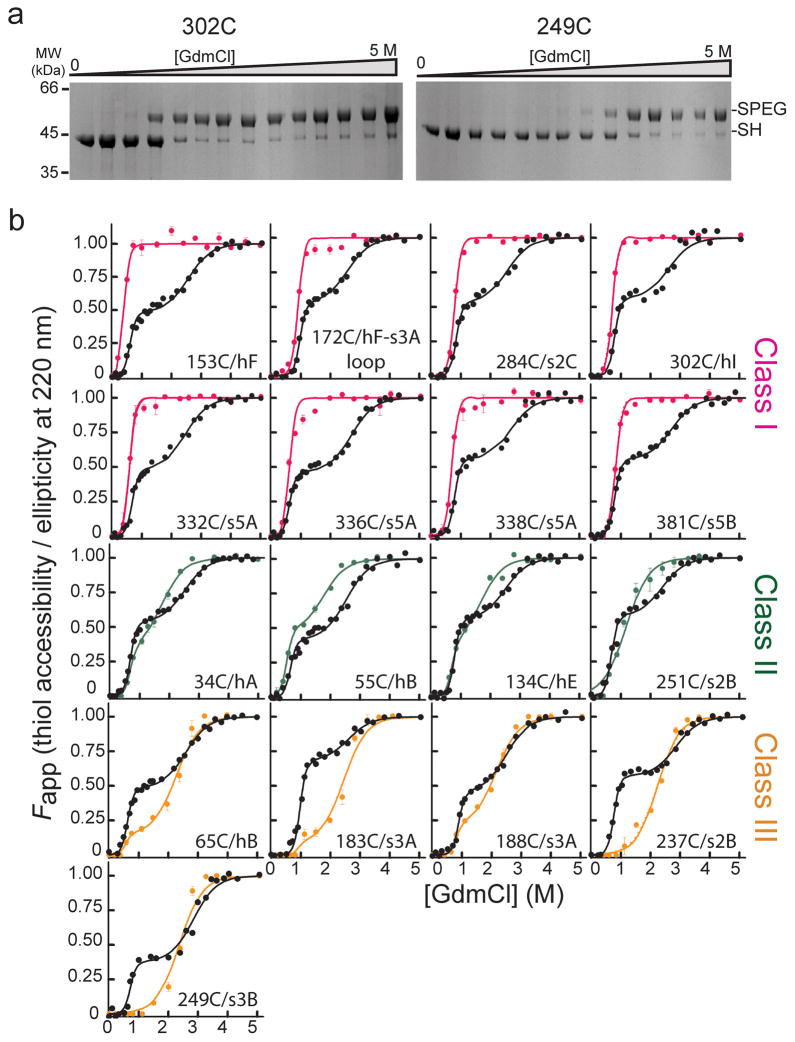

Cys accessibilities reveal a partially unfolded intermediate

The reactivities of the cysteine positions to PEG-Mal upon treatment with increasing concentrations of GdmCl were probed using a quantitative mobility shift SDS PAGE assay (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 3) and displayed three general behaviors, which we have grouped into classes (Fig. 2b). In Class I mutants, the sites of cysteine substitution become exposed to PEG-Mal at low denaturant (~1 M) and are fully exposed in the intermediate; in Class II mutants, the sites are partially exposed in the intermediate and become fully exposed at a denaturant concentration between the first transition and global unfolding, and in Class III mutants, the sites display low accessibility to modification (<20%) in the intermediate and only become accessible when the protein globally unfolds (2.6 M GdmCl). With few exceptions, the three classes of residues form spatially contiguous clusters within the native protein structure (Fig. 3). Class I residues 332, 336, and 338 are on the strand 5A, which is the strand that must release its native interactions with strand 3A and form new interactions with the inserted RCL in the loop-inserted state. Thus, the full accessibility of positions in this strand signals opening of the A-sheet as the intermediate becomes populated and suggests local unfolding. Full accessibility of positions 153 and 172 in this early transition argues that helix F unfolds cooperatively with strand 5A. Similarly, complete PEGylation of the side chain at position 302 suggests that helix I is also unfolded in the intermediate. Position 284 is involved in packing interactions with the RCL in the native state of α1AT, and its full exposure at low denaturant points to unraveling of the RCL local interactions as the intermediate is formed. Similarly, full accessibility of position 381 on strand 5B to PEGylation at low denaturant points to at least partial unfolding of the proximal structure. In sum, these results are consistent with local unfolding of strands 5A and 6A and spatially adjacent helices (F and I) along with B-sheet strands 4 and 5 as the sheet-opened intermediate forms. These unfolding events are also consistent with the change in CD signal at 222 nm, which signifies a loss of approximately 45% of native helical content as the intermediate forms.

Figure 2.

Accessibility of α1AT single cysteine variants as a function of denaturant and comparison to unfolding monitored by CD. (a) Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE results for the PEGylation of two representative single cysteine variants as a function of GdmCl concentration. Bands corresponding to the free and PEG-modified thiol are indicated by ‘-SH’ and ‘-SPEG’, respectively. (b) Comparison of the fractional accessibility of each cysteine to PEGylation (colored circles) with the unfolding of the variant α1AT monitored by CD (black circles). The solid lines through the data are the fit to a three-state or a two-state protein unfolding model as described in data analyses (see Supplementary Tables 2 and 3 for fit data). Data are grouped and colored according to the behavior of the specific cysteine site as a function of denaturant, i.e., Class I sites, which become fully accessible at low denaturant, are shown in pink, Class II sites, which become nearly 50% accessible at low denaturant and fully accessible as the protein globally unfolds, in green, and Class III sites, which are inaccessible or only slightly accessible over the first unfolding transition and then become fully accessible when the protein globally unfolds, in orange.

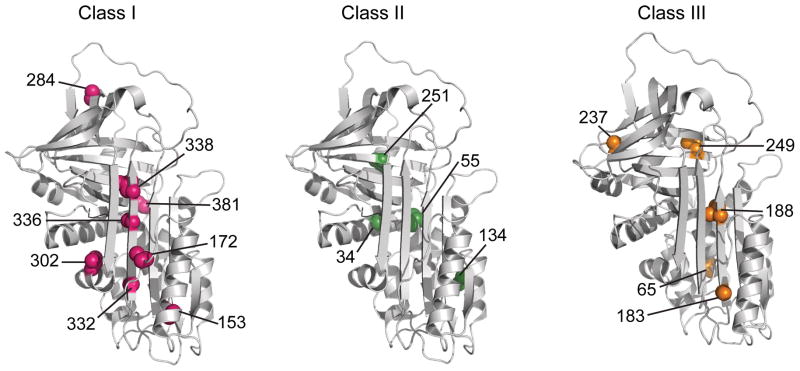

Figure 3.

Structural context of the cysteines belonging to the three classes with varying extents of PEGylation. Class I (pink), II (green), and III (orange) exhibit 100%, ~50% and <20% PEGylation, respectively, in the low GdmCl intermediate state of α1AT. The seventeen residues investigated in the current study are shown on the native structure of α1AT (PDB ID 1QLP)31.

Residues belonging to Class II, positions 34, 55, 134, and 251, display fractional PEG-Mal accessibility in the intermediate, suggesting the presence of dynamic fluctuations in these structural elements or that the structures to which they belong are retained, but regions onto which they are packed unfold. The first three of these positions map onto helices A, B and E at the N terminus of the protein, which are amphipathic and so their stability is affected by the features they pack against. We suggest that packing around these helices loosens in the intermediate, and that these secondary structures unfold as independent units with less GdmCl than required to fully disrupt the most stably packed regions of α1AT. Position 251 is on strand 3B, but its accessibility is substantially limited by helix H. Thus, its partial accessibility in the intermediate may reflect loosening of the helix H/B-sheet packing in the intermediate.

Residues in Class III are fully susceptible to PEGylation only when α1AT globally unfolds. They comprise two clusters in the protein, which we will designate IIIa and IIIb, each spatially contiguous: Class IIIa residues are in the N-terminal region of the A-sheet on strand 3A (residues 183 and 188) and on helix B (residue 65), which packs against strand 3A. The Class IIIa positions are accessible to PEGylation to a very small extent in the intermediate, and inspection of their packing partners (Supplementary Table I) suggests that partial unfolding of helix B and full unfolding of helix F in the intermediate could account for this exposure. Class IIIb residues are in strand 2B (residue 237) and 3B (residue 249), and their clear-cut behavior (viz., only accessible upon global unfolding) argues that this portion of the B-sheet remains stable in the intermediate.

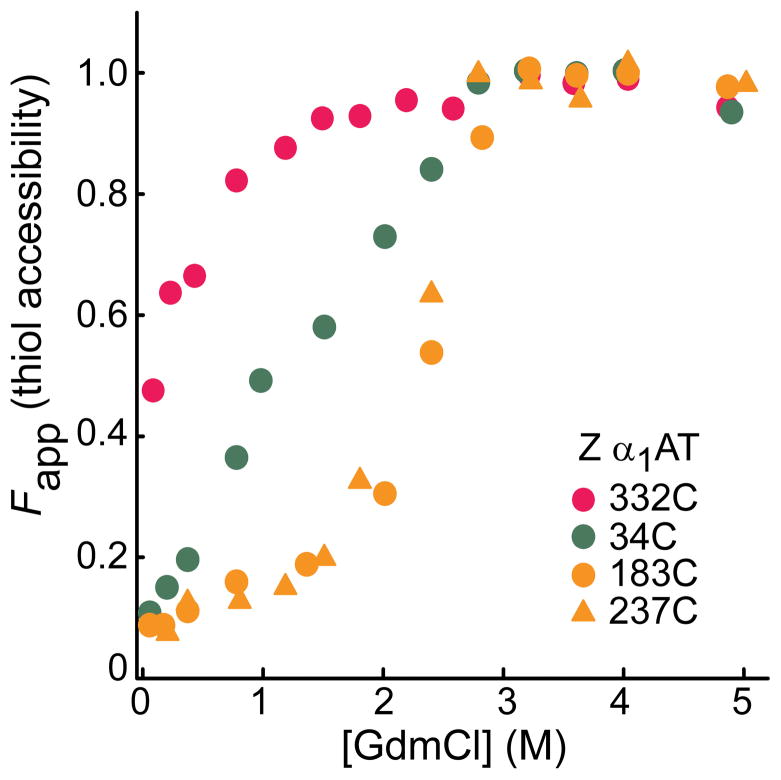

The Zvariant populates the same intermediate as WT α1AT

We validated the clinical significance of the cysteine accessibility data for the folding intermediate of WT α1AT by determining the solvent accessibility of cysteinyl thiols at four positions, 34 (Class II), 183 (Class IIIa), 237 (Class IIIb), and 332 (Class I) in one of the major pathogenic variants of α1AT, the Z variant, which harbors the mutation E342K22, at different concentrations of GdmCl. The results are fully consistent with our observations for the folding intermediate of the WT protein (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Fig. 4a). Far UV-CD spectra also confirmed that the global secondary structure of the intermediate state of the single cysteine-Z variants is similar to that of the intermediate form of the WT protein (data not shown). It should be mentioned here that refolding of Z α1AT is challenging due to its aggregation propensity. However, full reversibility of the transition from the unfolded to the intermediate state gave us access to the folding intermediate of Z α1AT.

Figure 4.

Solvent accessibility of single cysteines in the Z variant of α1AT. The intermediate state of the protein was formed from the denatured state, i.e., upon dilution from high (5M GdmCl) denaturant. Bands of the PEG-modified (-SPEG) and unmodified (-SH) protein in Supplementary Fig. 4a were quantitated to obtain fraction thiol accessibility. Note that refolding of the Z variant yields a state that is not identical to native, and that this accounts for the partial exposure of 332C at the lowest GdmCl concentration.

DISCUSSION

Our PEGylation data combined with previous results12 (Fig. 5a) enable the formulation of a structural model for the sheet-opened intermediate so critical to serpin function and pathology (Fig. 5b): Formation of the intermediate state is accompanied by local unfolding of the C-terminal half of the A-sheet, s5A-hI-s6A, which thus disengages from its N-terminal counterpart (s3A/s2A/s1A). Concurrently, helix F melts and dissociates from its packing interactions with the N-terminal strands of the A-sheet, and interactions of the RCL with the B- and C-sheets are disrupted. Interestingly, the labile s6A-hI-s5A-RCL-hF region is also the precise part of the protein that rearranges most during protease inhibition and during polymerization.

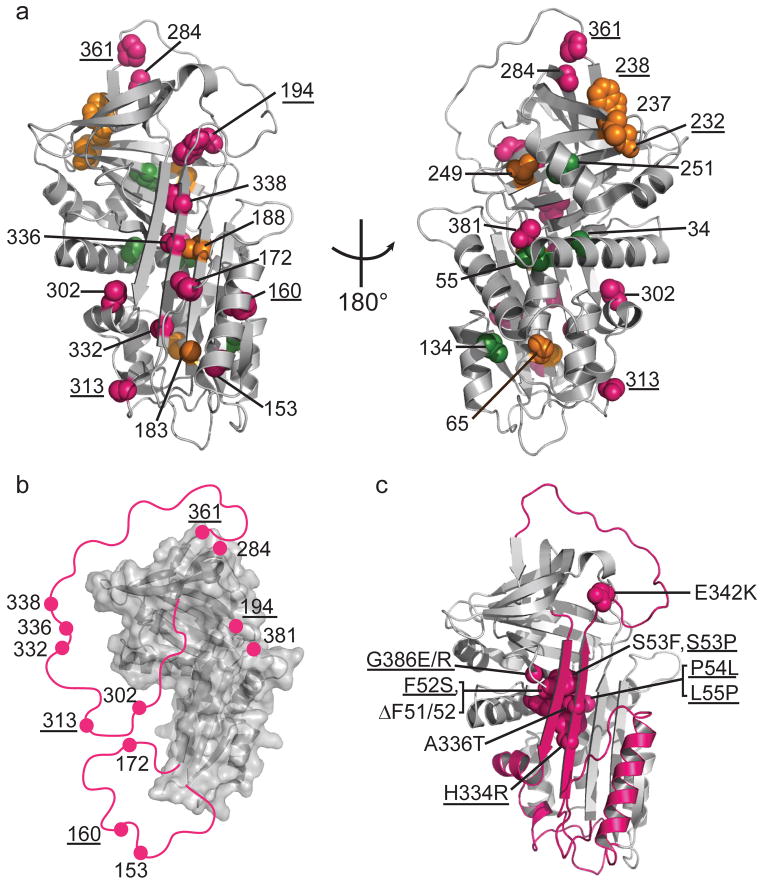

Figure 5.

Local unfolding leads to the sheet-opened intermediate of α1AT. (a) Cysteine positions are shown on the structure of native α1AT (PDB 1QLP)31 and colored by their accessibility behavior with pink, green and orange representing Class I, Class II, and III, respectively (see Fig. 2 and text for description of classes). Results for an additional six residue positions from previous work12,13,19 are indicated with appropriate coloring on the structure as well (labels are underlined) using the same color scheme. (b) The stable structural elements of the sheet-opened intermediate as inferred from cysteine accessibility data. In this structure, regions found to be accessible in the sheet-opened intermediate of α1AT are removed and indicated schematically by a pink line connecting to the remaining structure. (c) The five naturally occurring pathogenic point mutations in α1AT that produce full-length, polymerogenic protein and cause liver damage25,27 along with similar polymerogenic mutations reported for other serpins7 (underlined labels) are represented in pink spacefill on the native structure of α1AT. The backbone of the identified labile region is in pink.

While formation of the sheet-opened intermediate involves local unfolding of some regions of α1AT, other regions (Class III sites) remain unreactive to PEGylation until the global unfolding of α1AT, arguing that they are stably folded in the sheet-opened intermediate. This result is in marked disagreement with models arguing for distributed instability in serpins. The two regions that remain stably folded based on our data (i.e., strand 3A, hB and most of the B-sheet) and previous observations (positions 232 and 238 on the B-sheet12) also carry the most hydrophobic sequences of the protein. Together, these regions constitute a two-part denaturant-resistant hydrophobic core that likely serves as a scaffold for formation of subsequent structural elements in the loop-inserted serpin protease complex (or latent form).

The sheet-opened intermediate of α1AT is populated using low concentrations of denaturant, arguing that this conformation is present on the energy landscape of the native protein. Thus, a dynamic equilibrium between the native state and the locally unfolded, higher energy intermediate state is expected to occur even under native conditions, although the proportion of molecules in the open state will be low. The observations that exogenously added RCL-based peptides insert into the native state of various serpins23 and the slow conversion to a latent (loop-inserted) state3,4 compellingly support this model.

Consistent with the presence of a dynamic equilibrium is the fact that point mutations can shift the populations of the sheet-opened state. Such mutations are expected to modulate the susceptibility of the variant serpin to loop insertion, whether intramolecular or intermolecular. For example, the thermostable F51L shutter mutation is reported to stabilize the closed form of the central A-sheet of α1AT 24, and consistent with this role, we observed a shift in the GdmCl concentration required for full PEGylation of cysteine in position 332 on strand 5A in this mutant (Supplementary Fig. 4b,c). By contrast, all pathogenic mutations in α1AT that result in toxic polymers and consequent liver disease7,25 are located in regions that would be expected to favor sheet opening, based on our data (Fig. 5c). The Z mutation described above, which leads to loss of a salt bridge between strands 5A and 6A22 and thus further destabilizes the labile s6A-hI-s5A-RCL-hF region, shifts the equilibrium from the native state to the aggregation-prone A-sheet-opened intermediate, and concomitantly increases risk of aggregation. As expected for a shift of the α1AT dynamically sampled equilibrium towards the sheet-opened state in the case of the Z variant, recombinant native Z α1AT has been reported to form a binary complex with a strand-mimicking reactive loop hexapeptide more rapidly than WT 26. Mutants ΔF51 and ΔF52 on strand 6B and S53F in the loop following strand 6B are in the part of the B-sheet (known as the ‘shutter’ region) upon which strands 5A and 6A pack; these mutations thus weaken the connections of the labile s6A-hI-s5A-RCL-hF element to the rest of the structure, favoring sheet opening, and enhancing aggregation propensity. The rare α1AT allele PI W reported to cause infantile liver disease27 harbors a mutation (A336T) on strand 5A facing the shutter region and the larger side chain disrupts packing. Additionally, most naturally occurring polymerogenic mutations in other serpins, such as in antithrombin (P54T/S), C1 inhibitor (F52S, P54L), α1-antichymotrypsin (L55P), and neuroserpin (S53P, S56R, H334R, G386E/R)7, map to the labile region we identified in α1AT (Fig. 5c). The s6A-hI-s5A-RCL-hF region can thus be considered to be the “Achilles heel” of serpins, as a delicate balance between stable folding onto the rest of the serpin and lability is critical to serpin function.

Our results suggest that the aggregation-prone intermediate of α1AT may form either from the unfolded state, as previously proposed28 to occur physiologically upon biosynthesis of nascent α1AT and translocation into the lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum, or from the native state by dynamic sampling of the sheet-opened state on the folding landscape. The principal molecular mechanism of antitrypsin deficiency is the former, which results in intracellular accumulation of protein polymer in the liver and consequent plasma deficiency. Nonetheless, inactive polymers of variant α1AT corresponding to Z (E342K), Siiyama (S53F), and Mmalton (ΔF52) have also been isolated from the plasma and lungs of patients29,30; such polymers must arise from dynamic sampling of the sheet-opened state from the native state of the protein.

In summary, our results provide a detailed structural model of the transient, functionally crucial intermediate of the serpin α1AT. Our findings are consistent with a dynamic serpin folding landscape in which the s6A-hI-s5A-RCL-hF region is labile, and its unfolding enables facile switching of conformations in serpins. Reciprocally, our site-specific reactivity data show that part of the serpin structure remains well folded and thus inaccessible in the sheet-opened intermediate. These results help to explain pathogenic mutations that cause disease by serpin polymerization and may offer routes to design of therapeutic agents for treatment of serpinopathies.

METHODS

Mutagenesis, protein expression and purification

Single cysteine variants were generated using the QuikChange procedure (Stratagene) in a cysteine-free C232S background of a naturally occurring variant of human α1AT carrying R101H and E376D mutations in the plasmid pEAT8-13732.

Wild type and active single cysteine α1AT variants were expressed and purified as soluble protein from E. coli BL21(DE3) using a newly developed high-yield protein purification protocol. In brief, thirty minutes prior to IPTG induction proline and sodium chloride were added to the growing culture to a final concentration of 20 mM and 0.3 M, respectively, to improve protein solubility33. After induction, the temperature was reduced from 37 to 30 °C and the culture allowed to incubate for 4 h. Cells were lysed using a Microfluidizer® (M-110L, Microfluidics, Newton, MA), and the soluble fraction in 10 mM bis-Tris pH 5.92 was applied onto a Q- Sepharose fast flow (Sigma) column, which was run at pH 5.92. Fractions containing α1AT (70 – 80% pure) were buffer exchanged into 10 mM HEPES, pH 8.0 using the Amicon Ultra-15 concentrator (30 kDa MW cut-off, from Millipore) and further purified on a MonoQ™ 5/50 global column (GE Biosciences) at pH 8.0.

Single-cysteine Z variants were expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3) cells induced with 0.5 mM IPTG for 4 h at 37 °C and purified from inclusion bodies. Cellular debris loosely associated with the cell pellet (yellow translucent) was physically removed by scraping, and the cell pellet was washed with 10 mM HEPES, pH 8.0 containing 0.01% NP40. The final washed cell pellet (now white) was solubilized in 6 M urea for 10 m, and the protein was purified using a HiTrap Q HP (5 ml) column (GE Biosciences) in 6 M urea with 1 mM β-mercaptoethanol. Fractions containing α1AT (>90% pure) were buffer exchanged into 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.0, containing 5 M GdmCl. Identities of the single-cysteine Z variants were confirmed by mass spectrometry. Experiments with the Z-variants were carried out using the tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine-reduced, GdmCl-unfolded protein. All protein concentrations were determined using absorbance at 280 nm.

Screening of active α1AT variants

A qualitative screen was used to check activity of the single-cysteine mutants before purification: Porcine pancreatic elastase (Sigma) or bovine pancreatic trypsin (Sigma) was added to cell lysate and inhibitory complexes with α1AT were detected by Western blot using a monoclonal α1AT antibody (Abcam) or polyclonal anti-elastase antibody (Abcam).

Equilibrium stability measurements

Equilibrium stabilities were determined by GdmCl titration of 1–2 μM protein in 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.0, equilibrated at 25 °C for 2 h and following the CD signal at 220 nm on a Jasco J715 spectropolarimeter. The data were curve-fitted to a three-state unfolding model34.

PEGylation assay

In a typical PEGylation reaction, 1–2 μM protein samples were prepared either by equilibration in increasing GdmCl (0 to 5.0 M), or by reversible formation of the 1.5 M GdmCl intermediate from native or denatured states. In all cases, 0.1 ml samples were subjected to a pulse of at least 100-fold molar excess of PEG-Mal (prepared in water just before use), for one minute at 25 °C with shaking at 350 rpm in an Eppendorf thermomixer. The pulse duration of one minute was based on near 80–90% PEG-modification observed for a fully unfolded protein in high GdmCl. The reaction was quenched with ~2000-fold molar excess (relative to the protein) of cysteine-HCl followed by immediate addition of 0.2 ml of 0.1% (v/v) formic acid and trichloroacetic acid (TCA) to a final concentration of 16% (v/v). Maintaining low pH by using formic acid and the acid form of cysteine ensured efficient quenching, which was also experimentally verified by the absence of PEGylation of native or fully unfolded protein in the presence of quencher (data not shown). TCA-precipitated samples were analyzed on a 10% Tricine SDS-PAGE. Band quantitation of the Coomassie-stained gel was carried out using the Gene Tools software provided with the Syngene G:box gel documentation system. The rate of PEGylation and quenching35,36 is fast enough not to perturb the equilibrium, and hence PEGylation fraction quantitatively measures the population of buried and exposed Cys-containing protein reliably and reproducibly.

Knowing the risk of protein aggregation at long incubation times under potentially aggregating conditions, we performed a control PEGylation experiment at a short incubation time wherein aggregation is minimal, if any occurs at all. We could only do this control at a high enough denaturant concentration to ensure rapid equilibration. At 1.5 M GdmCl, the folding intermediate was formed reversibly either from the native or the denatured state within 5 m (Supplementary Fig. 5a). PEG-modification results with all the single cysteine constructs under these conditions show the same pattern as the data obtained at longer incubation times (Supplementary Fig. 5b). Additionally, glutaraldehyde cross-linking in well-equilibrated protein samples reconfirmed that protein samples indeed remain predominantly monomeric (at least 70 to 80%) (Supplementary Fig. 6).

Analysis of PEGylation data

The fraction of protein with the cysteinyl-thiol PEGylated (FS-PEG) was calculated as: FS-PEG = BIS-PEG/[BIS-PEG + BISH], where BI represents the band intensity obtained from band quantitation as described above; and SH and S-PEG refer to the unmodified and PEGylated thiol, respectively. A fully unfolded protein is expected to have FS-PEG of 1.0, however a value of 0.8 to 0.9 was observed for most of the cysteine mutants, except in the case of V134C and A153C, which showed somewhat lower reactivity. Close examination of the sequence around these two positions indicates that each follows a negatively charged residue, which likely reduces the reactivity of the cysteinylthiol37. The FS-PEG data were converted to the fractional change as described above, and are referred to as ‘fraction thiol accessibility’. The monophasic or biphasic transition was treated similar to a protein-unfolding curve and fit to a two-state or a three-state unfolding model34. Equally good fits of the data were obtained using the m value, mIN and mUI of −5.67 kcal mol−1 M−1 and −1.52 kcal mol−1 M−1, respectively, that were obtained from the CD unfolding data.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank C. L. Cooney (MIT) for providing a modified form of plasmid pEAT8 (see Methods), originally from M. H. Yu (Korea Institute of Science and Technology). We acknowledge with thanks Steve Eyles and the UMass Amherst mass spectrometry facility for ESI-MS results, and Eugenia Clerico and Anne Gershenson for stimulating discussions and critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by grants from the NIH (OD-00045 to L.M.G.) and the Alpha-1 Foundation (to B.K.).

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

B.K. and L.M.G. designed the experiments, B.K. performed the experiments, B.K. and L.M.G. interpreted results, and B.K. and L.M.G. wrote the manuscript.

References

- 1.Gettins PG. Serpin structure, mechanism, and function. Chem Rev. 2002;102:4751–4804. doi: 10.1021/cr010170+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huntington JA, Read RJ, Carrell RW. Structure of a serpin-protease complex shows inhibition by deformation. Nature. 2000;407:923–926. doi: 10.1038/35038119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dupont DM, et al. Biochemical properties of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1. Front Biosci. 2009;14:1337–1361. doi: 10.2741/3312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mushunje A, Evans G, Brennan SO, Carrell RW, Zhou A. Latent antithrombin and its detection, formation and turnover in the circulation. J Thromb Haemost. 2004;2:2170–2177. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2004.01047.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaslik G, et al. Effects of serpin binding on the target proteinase: global stabilization, localized increased structural flexibility, and conserved hydrogen bonding at the active site. Biochemistry. 1997;36:5455–5464. doi: 10.1021/bi962931m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang Z, Mottonen J, Goldsmith EJ. Kinetically controlled folding of the serpin plasminogen activator inhibitor 1. Biochemistry. 1996;35:16443–16448. doi: 10.1021/bi961214p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gooptu B, Lomas DA. Conformational pathology of the serpins: themes, variations, and therapeutic strategies. Annu Rev Biochem. 2009;78:147–176. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.78.082107.133320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tran ST, Shrake A. The folding of alpha-1-proteinase inhibitor: kinetic vs equilibrium control. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2001;385:322–331. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2000.2186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yamasaki M, Li W, Johnson DJ, Huntington JA. Crystal structure of a stable dimer reveals the molecular basis of serpin polymerization. Nature. 2008;455:1255–1258. doi: 10.1038/nature07394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yamasaki M, Sendall TJ, Harris LE, Lewis GM, Huntington JA. The loop-sheet mechanism of serpin polymerization tested by reactive center loop mutations. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:30752–30758. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.156042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ekeowa UI, et al. Defining the mechanism of polymerization in the serpinopathies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:17146–17151. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004785107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.James EL, Whisstock JC, Gore MG, Bottomley SP. Probing the unfolding pathway of alpha1-antitrypsin. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:9482–9488. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.14.9482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cabrita LD, Whisstock JC, Bottomley SP. Probing the role of the F-helix in serpin stability through a single tryptophan substitution. Biochemistry. 2002;41:4575–4581. doi: 10.1021/bi0158932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Whisstock JC, Bottomley SP. Structural biology: Serpins’ mystery solved. Nature. 2008;455:1189–1190. doi: 10.1038/4551189a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsutsui Y, Wintrode PL. Cooperative unfolding of a metastable serpin to a molten globule suggests a link between functional and folding energy landscapes. J Mol Biol. 2007;371:245–255. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.05.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seo EJ, Im H, Maeng JS, Kim KE, Yu MH. Distribution of the native strain in human alpha 1-antitrypsin and its association with protease inhibitor function. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:16904–16909. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001006200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lu J, Deutsch C. Pegylation: a method for assessing topological accessibilities in Kv1.3. Biochemistry. 2001;40:13288–13301. doi: 10.1021/bi0107647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bottomley SP, Hopkins PC, Whisstock JC. Alpha 1-antitrypsin polymerisation can occur by both loop A and C sheet mechanisms. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;251:1–5. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tew DJ, Bottomley SP. Probing the equilibrium denaturation of the serpin alpha(1)-antitrypsin with single tryptophan mutants; evidence for structure in the urea unfolded state. J Mol Biol. 2001;313:1161–1169. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Powell LM, Pain RH. Effects of glycosylation on the folding and stability of human, recombinant and cleaved alpha 1-antitrypsin. J Mol Biol. 1992;224:241–252. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90587-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Knaupp AS, Levina V, Robertson AL, Pearce MC, Bottomley SP. Kinetic instability of the serpin Z alpha1-antitrypsin promotes aggregation. J Mol Biol. 2010;396:375–383. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.11.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brantly M, Courtney M, Crystal RG. Repair of the secretion defect in the Z form of alpha 1-antitrypsin by addition of a second mutation. Science. 1988;242:1700–1702. doi: 10.1126/science.2904702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhou A, Stein PE, Huntington JA, Carrell RW. Serpin polymerization is prevented by a hydrogen bond network that is centered on His-334 and stabilized by glycerol. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:15116–15122. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211663200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim J, Lee KN, Yi GS, Yu MH. A thermostable mutation located at the hydrophobic core of alpha 1-antitrypsin suppresses the folding defect of the Z-type variant. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:8597–8601. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.15.8597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zaimidou S, et al. A1ATVar: a relational database of human SERPINA1 gene variants leading to alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency and application of the VariVis software. Hum Mutat. 2009;30:308–313. doi: 10.1002/humu.20857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levina V, et al. Expression, purification and characterization of recombinant Z alpha(1)-antitrypsin--the most common cause of alpha(1)-antitrypsin deficiency. Protein Expr Purif. 2009;68:226–232. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2009.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clark P, Chong AY. Rare alpha 1 antitrypsin allele PI W and a history of infant liver disease. Am J Med Genet. 1993;45:674–676. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320450603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yu MH, Lee KN, Kim J. The Z type variation of human alpha 1-antitrypsin causes a protein folding defect. Nat Struct Biol. 1995;2:363–367. doi: 10.1038/nsb0595-363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lomas DA. New insights into the structural basis of alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency. Quart J Med. 1996;89:807–812. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/89.11.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mahadeva R, et al. Polymers of Z alpha1-antitrypsin co-localize with neutrophils in emphysematous alveoli and are chemotactic in vivo. Am J Pathol. 2005;166:377–386. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)62261-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Elliott PR, Pei XY, Dafforn TR, Lomas DA. Topography of a 2.0 A structure of alpha1-antitrypsin reveals targets for rational drug design to prevent conformational disease. Protein Sci. 2000;9:1274–1281. doi: 10.1110/ps.9.7.1274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Laska ME. PhD thesis. Massachusetts Institute of Technology; Cambridge, MA: 2001. The effect of dissolved oxygen on recombinant protein degradation in Escherichia coli. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ignatova Z, Gierasch LM. Inhibition of protein aggregation in vitro and in vivo by a natural osmoprotectant. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:13357–13361. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603772103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nath U, Udgaonkar JB. Perturbation of a tertiary hydrogen bond in barstar by mutagenesis of the sole His residue to Gln leads to accumulation of at least one equilibriumfolding intermediate. Biochemistry. 1995;34:1702–1713. doi: 10.1021/bi00005a027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weissman JS, Kim PS. Reexamination of the folding of BPTI: predominance of native intermediates. Science. 1991;253:1386–1393. doi: 10.1126/science.1716783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hansen RE, Winther JR. An introduction to methods for analyzing thiols and disulfides: Reactions, reagents, and practical considerations. Anal Biochem. 2009;394:147–158. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2009.07.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Salsbury FR, Jr, Knutson ST, Poole LB, Fetrow JS. Functional site profiling and electrostatic analysis of cysteines modifiable to cysteine sulfenic acid. Protein Sci. 2008;17:299–312. doi: 10.1110/ps.073096508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.