Abstract

The extracellular calcium-sensing receptor (CaSR) has recently been recognized as an l-amino acid sensor and has been implicated in mediating cholecystokinin (CCK) secretion in response to aromatic amino acids. We investigated whether direct detection of l-phenylalanine (l-Phe) by CaSR results in CCK secretion in the native I cell. Fluorescence-activated cell sorting of duodenal I cells from CCK-enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP) transgenic mice demonstrated CaSR gene expression. Immunostaining of fixed and fresh duodenal tissue sections confirmed CaSR protein expression. Intracellular calcium fluxes were CaSR dependent, stereoselective for l-Phe over d-Phe, and responsive to type II calcimimetic cinacalcet in CCK-eGFP cells. Additionally, CCK secretion by an isolated I cell population was increased by 30 and 62% in response to l-Phe in the presence of physiological (1.26 mM) and superphysiological (2.5 mM) extracellular calcium concentrations, respectively. While the deletion of CaSR from CCK-eGFP cells did not affect basal CCK secretion, the effect of l-Phe or cinacalcet on intracellular calcium flux was lost. In fact, both secretagogues, as well as superphysiological Ca2+, evoked an unexpected 20–30% decrease in CCK secretion compared with basal secretion in CaSR−/− CCK-eGFP cells. CCK secretion in response to KCl or tryptone was unaffected by the absence of CaSR. The present data suggest that CaSR is required for hormone secretion in the specific response to l-Phe by the native I cell, and that a receptor-mediated mechanism may inhibit hormone secretion in the absence of a fully functional CaSR.

Keywords: amino acid sensing, protein sensing, enteroendocrine

dietary protein is satiating, in part, due to the release of cholecystokinin (CCK) from duodenal enteroendocrine “I” cells. Aromatic amino acids, particularly l-phenylalanine (l-Phe), are known to elevate plasma CCK levels and reduce food intake in humans (2), rhesus macaques (14), and rats (1). Additionally, in the murine enteroendocrine cell line STC-1, l-Phe activates calcium channels and intracellular signaling pathways, resulting in CCK secretion (21).

The extracellular calcium-sensing receptor (CaSR) was originally cloned from the bovine parathyroid gland (5) and is well established for its role in serum calcium homeostasis (17, 19). This G protein-coupled receptor is directly activated in response to inorganic and organic polycations and is also allosterically activated by phenylalkylamine type II calcimimetics and aromatic l-amino acids, such as l-Phe, in the presence of physiological calcium concentrations (12). The CaSR has been proposed to function as an l-amino acid sensor and as a mediator of hormone secretion in the gastrointestinal tract. Indeed, among many other tissue types, the CaSR has also been localized on the pancreatic β-cell (33, 39), enteroendocrine cells of the colonic mucosa (39), and gastrin-secreting G cells of the stomach (34).

Given that l-Phe is a known CCK secretagogue, the possibility remains that the CaSR mediates amino acid-induced CCK secretion by the I cell (11). In a recent STC-1 cell study, phenylalanine-induced mobilization of intracellular calcium and CCK secretion was inhibited with the allosteric CaSR inhibitor NPS2143 (16), further supporting a putative role for the CaSR in CCK secretion. However, it is unknown whether this receptor is functionally expressed by the native intestinal I cell, and whether it functions to regulate l-amino acid-induced CCK secretion as a nutrient sensor.

In this study, we tested the hypothesis that the CaSR serves as an amino acid sensor, modulating l-Phe-induced CCK secretion from native intestinal I cells isolated from CCK-enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP) mice. We demonstrate that CaSR is expressed on these cells and is required for hormone secretion in response to direct stimulation with l-Phe, and that this response is enhanced in the presence of additional extracellular calcium.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

l-Phe, d-Phe, and CaCl2 (cell culture grade) were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Tryptone, a pancreatic digest of casein, was obtained from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA). Cinacalcet was purified from Sensipar (Amgen, Thousand Oaks, CA).

Experimental animals.

Transgenic mice with CCK promoter-driven eGFP were obtained from the Mutant Mouse Regional Resource Center (Davis, CA) and were used as the wild-type (WT) control (CaSR+/+ PTH+/+ CCK-eGFP) for acutely isolated cell studies.

CaSR and parathyroid hormone (PTH) double homozygous knockout (KO) mice (a generous gift of Drs. Claudine Kos and Martin Pollack, Brigham and Women's Hospital) were previously derived and characterized (19). Knocking out the PTH was required to rescue the CaSR−/− phenotype from bone abnormalities and premature death and was assumed to not affect gastrointestinal hormone secretion (17). The CaSR and PTH double homozygous KO mice (CaSR−/− PTH−/−) were crossed with the CCK-eGFP transgenic mice to evaluate the functional role of CaSR in isolated CCK-eGFP cells.

Animals were bred and maintained according to the National Institutes of Health Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (ACUC) guidelines, following independent protocol review and approval by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases ACUC.

Mouse genotyping.

Tail DNA was extracted using hot 50 mM NaOH and 1 M Tris·HCl, pH 8.0. Genomic DNA samples were amplified for CaSR and PTH using primers described previously (19). Presence of the eGFP transgene was determined using the following primers: EGFP-F1, 5′ CCA CCA GTT CAG CGT GTC C 3′; and EGFP-R1, 5′ GTT GTA CTC CAG CTT GTG C 3′. All PCR reactions were performed using the Invitrogen Platinum Taq DNA Polymerase High Fidelity system (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) with 35 cycles of 94°C for 2 min, 94°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 68°C for 45 s to 1 min, with a final 7-min extension at 68°C. Amplified samples were resolved on a 1.5% ethidium-bromide-stained agarose gel and examined for positive band products of the appropriate sizes.

Isolation of intestinal endocrine cells.

Adult mice were euthanized, and a 5- to 6-cm proximal segment of duodenum was collected, washed, and incubated in 1 mM EDTA-Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS) solution for 20 min in a 37°C shaking water bath. After washing, tissue was incubated for another 20 min in 50–75 U/ml collagenase (Worthington Chemical, CLPSA grade) in cell culture media. Cells were resuspended and filtered through 30-μm and 20-μm nylon filters (Spectrum Laboratories, Laguna Hills, CA) to obtain a dispersed single-cell population. Cells were washed, resuspended in fluorescent-activated cell sorting (FACS) sorting buffer (5% FBS, 50 μg/ml DNase I in phenol-free DMEM), and underwent FACS (BD FACS ARIA machine, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA).

Approximately 30,000 eGFP cells were sorted based on GFP fluorescence (Fig. 1, A and B) and collected into a tube with 10% FBS-phenol-free DMEM. For RT-PCR studies, a non-eGFP cell population (FITC < 102), comprising primarily of enterocytes, but may also include goblet cells, lymphocytes, and non-eGFP endocrine cells, was simultaneously sorted into a separate collection tube. Examination of isolated eGFP cells demonstrated minimal to no mRNA contamination from enterocytes or goblet cells (data not shown) and were confirmed to be both GFP and CCK immunopositive (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

Acute isolation of cholecystokinin (CCK)-enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP) (“I”) cells with fluorescent-activated cell sorting (FACS). Single-cell suspensions from the duodenal mucosa were analyzed and selected based on green fluorescent protein (GFP) fluorescence. Distinct non-eGFP (light gray) and eGFP (black) cell populations were visualized by flow cytometric analysis pre- (A) and postsorting (B). The P4 gating indicates the cutoff point between non-eGFP and eGFP cells. Postsorted eGFP-negative cells were determined to be dead cells by Trypan blue exclusion. C: all sorted eGFP-positive cells (green) were confirmed to be both GFP positive (blue) and CCK positive (red) by immunostaining. PE-A, phycoerythrin area; GFP-A, GFP area.

Immunofluorescent staining.

For confirmatory studies, FAC-sorted eGFP cells were dried on positively charged slides, washed in PBS, and stained with a 1:2,000 dilution of rabbit anti-CCK antibody (Peninsula Laboratories, Torrance, CA) and a 1:1,000 dilution of mouse anti-GFP in 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA)-PBS overnight at 4°C. After washing, slides were incubated for 1 h with Alexafluor 594 goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody and Pacific Blue conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody (Invitrogen).

For CaSR immunostaining of whole tissue sections, previously genotyped mice were euthanized and intracardially perfused with cold 0.9% NaCl, followed by fixation with fresh cold 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS. Stomach antrum and ∼2–3 cm of proximal duodenum were collected, trimmed of pancreatic tissue, and submerged in 4% PFA-PBS for 2–3 h at room temperature before final rinse with PBS and transfer into 70% ethanol. Tissue was submitted to Histoserv (Germantown, MD) for paraffin embedding and sectioning (5-μm slices). Sections were deparaffinized, rehydrated, and underwent antigen retrieval, as previously described (15). Briefly, slides were placed in a beaker containing citrate buffer solution (pH 6.0) with 0.1% Tween and boiled over a hotplate for 40 min. The sections were immediately cooled in Tris-buffered saline (0.05 mol/l; pH 7.6) containing 5% goat serum for 30 min, followed by incubation with PBS blocking buffer containing 3% BSA for 30 min. Sections were incubated with either 1:200, 1:500, or 1:1,000 dilutions of mouse monoclonal anti-human CaSR antibody (ADD; Affinity Bioreagents, Rockford, IL) in blocking buffer for 48 h at 4°C. After PBS washing, slides were incubated in 1:1,000 goat anti-mouse IgG AlexaFluor secondary antibody (Invitrogen) in blocking buffer for 1 h at room temperature. Coverslips were mounted with Dako Glycerogel mounting medium (Dako, Carpinteria, CA) and viewed under a Zeiss LSM 510 Meta confocal microscope. After viewing, coverslips were carefully removed by incubating slides in a warm water bath. The blocking procedure was repeated, and the slides were incubated with a 1:500 dilution of rabbit anti-CCK antibody (Peninsula Laboratories/Bachem, Torrance, CA) overnight at 4°C, followed by a 1:500 dilution of goat anti-rabbit AlexaFluor secondary antibody for 2 h at room temperature. Fresh coverslips were remounted, and slides were viewed under confocal microscopy with LP650 and BP 505–530 emission filters to ensure no bleed-through of green fluorescence into the red spectrum. Slides with a CaSR dilution of 1:500 and 1:1,000 were most optimal. A similar procedure was followed, with the fluorescent spectra of the secondary antibodies reversed. For immunostaining of fresh tissue, duodenal villus samples were isolated by incubation in 2 mM EDTA-DPBS (30 min, 4°C), followed by gentle pipetting and centrifugation (250 g, 2 min). The villus samples were immediately incubated with mouse anti-CaSR monoclonal antibody (1:50; MA1–934, Thermo Scientific, Fremont, CA) for 30 min at 4°C, centrifuge washed, and incubated with the appropriate Alexa Fluor 633 anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody (Invitrogen) for 30 min at 4°C in 1% BSA-DPBS. After being washed twice with cold DPBS, immunostained villi were fixed with 4% PFA and analyzed by confocal microscopy.

RNA extraction and RT-PCR.

RNA was extracted from FAC-sorted CCK-eGFP-positive cells and non-eGFP cells with Trizol Reagent (Invitrogen) and 20% phenol-chloroform isoamyl-alcohol (Invitrogen). The aqueous phase was ethanol precipitated and resuspended in 11.5 μl of DPEC water. Reverse transcription of total RNA was performed using the High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, San Jose, CA) and run under the following thermocylcer conditions: 10 min at 25°C, 60 min at 50°C, and 5 min at 94°C. The qPCR reaction was performed using an Applied Biosystems Step One System with a 20-μl reaction volume made of 2× master mix (with 1 μl target probe), 20× assay mix, 10× amplified cDNA sample, and water using optimized target probes (Applied Biosystems) for CaSR (Mm00443375_m1), Tas1R3 (Mm00473459_g1), Tas1R1 (Mm00473433_m1), GPR92 (Mm02621109_s1), and PepT1 (slc15a1; Mm00453524_m1). The ABI preset cycling conditions were 1 cycle for 2 min at 50°C and 1 cycle for 10 min at 95°C, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 1 min. Detection of amplification relied on monitoring a reporter dye (6-FAM).

Gene expression was analyzed using the comparative CT method (ABI User Bulletin 2). Relative gene expression was calculated relative to the housekeeping gene, mouse β-actin, and represented as 2−ΔCT × 1,000. Fold gene expression differences for target genes in the CCK-eGFP cell population relative to the non-eGFP cell population were calculated as 2−ΔΔCT, using the non-eGFP cell population as the calibrator. Statistical significance was determined using a paired t-test between the eGFP and non-eGFP cell ΔCT values.

Confocal Ca2+ imaging of CCK-eGFP cells.

Changes in intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) in CCK-eGFP cells were measured by confocal Ca2+ imaging using the Ca2+-sensitive indicator dye, Quest Rhod4 (AAT Bioquest, Sunnyvale, CA). Quest Rhod4 was chosen to minimize overlapping GFP fluorescence emission over 560 nm (i.e., the longest end of eGFP emission spectrum) at 543-nm excitation. In brief, a single-cell suspension of intestinal epithelial cells was prepared, as described previously with EDTA-DPBS and collagenase. After washing, the cells were suspended and loaded with 2 μM Quest-Rhod4 in Hank's balanced salt solution supplemented with 10 mM HEPES (HHBSS with 1.26 mM calcium and ∼1 mM magnesium, pH 7.4) and incubated in subdued light for 30 min at room temperature. Quest Rhod4-loaded cells were then plated on a 15-well μ-slide (ibidi, Verona, WI) and imaged using a Zeiss LSM510 Meta confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss). Before the Ca2+ imaging, the target CCK-eGFP cell was identified using a 505–550 band-pass filter at 488-nm excitation. The Ca2+ imaging experiment proceeded using a 560–615 nm emission band-pass filter at 543-nm excitation to measure relative fluorescence intensity (FI) of Quest Rhod4 from the target cell. For each experiment, time-dependent acquisition was performed at 1-s intervals for over 10 min at room temperature. For the data analysis, maximum %increase over baseline was calculated as follows: [peak FI − basal FI]/basal FI × 100.

CCK releasing assay of FAC-sorted cells.

On any given day, cells from only one genotype could be sorted and evaluated for hormone secretion. After sorting, cells were washed and suspended in ice-cold HHBSS to reach a concentration of 1 × 104 cells/ml. Approximately 500–1,000 cells/well were aliquoted into a collagen-coated 96-well plate containing a 2× concentration of ligands. The cells were incubated, in a total volume of 200 μl, with the following treatments for 30 min at 37°C, 5% CO2: HHBSS (vehicle), 30 mM l-Phe, 2.54 mM CaCl2, 30 mM l-Phe and 2.54 mM CaCl2, 30 mM d-Phe, 1% Tryptone, 4 μM linolenic acid, and 50 mM KCl. Cinacalcet was resuspended as a 1 mM stock in 100% DMSO and freshly diluted with HHBSS to a 2× working concentration. The final concentration of DMSO for all cinacalcet dosages was 0.05%. All treatments were tested in triplicate wells, and each n was considered as the average of triplicate responses from one single-cell preparation. Total CCK content was determined by adding 0.2% Triton X-100 in distilled water in wells designated for total cell contents. Secretion was halted by placing the plate on ice for 5 min. Cells were pelleted by centrifugation (720 g, 10 min, 4°C), and up to 50 μl of supernatant were retrieved and saved at −20°C until measured. Commercial lactate dehydrogenase assays did not possess adequate sensitivity to monitor cell toxicity in populations of <1,000 cells; therefore, viability of cells was assessed following each experiment with Trypan blue exclusion and direct epifluorescent microscopy for presence and intensity of eGFP cells. CCK for each treatment replicate was measured in duplicate using the 4-day incubation protocol of a commercially available EURIA-CCK Radioimmunoassay Kit (Alpco Diagnostics, Salem, NH).

Data analysis and statistics.

A one-sample t-test was run to compare the effect of individual ligands on CCK secretion compared with baseline within each genotype. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism version 5 (San Diego, CA), and significance was accepted at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

CCK-eGFP cells express CaSR.

Using quantitative RT-PCR, a pure population of acutely isolated CCK-eGFP cells (Fig. 1) was compared with a non-eGFP cell population for the presence of CaSR mRNA transcripts (Fig. 2). Out of five separate non-eGFP cell populations, only two populations yielded detectable CaSR gene expression with a CT value < 40. To calculate relative gene expression with a ΔCT value, the CT values of the other three populations were set to 40. Using this overestimated ΔCT value for non-eGFP cells, we calculated that CCK-eGFP cells expressed at least 900-fold greater CaSR transcript than non-eGFP cells (Fig. 2; P < 0.0001). The expression for T1R3 was equivalent between CCK-eGFP and non-eGFP cells, but T1R1 expression was not detectable in either population. In addition, mRNA expression for putative peptone receptor GPR92 and the oligopeptide transporter PepT1 was equivalent between CCK-eGFP and non-eGFP cells.

Fig. 2.

Gene expression of putative peptide or amino acid sensing receptor proteins in CCK-eGFP cells relative to non-eGFP cells. Gene transcripts for calcium-sensing receptor (CaSR) are significantly elevated in CCK-eGFP cells, whereas gene expression for PepT1, GPR92, and T1R3 are equivalent to that expressed in the non-eGFP cell population. T1R1 transcript was undetectable in both populations. Gene fold expression of 1 is regarded as equivalent to the non-eGFP population. Significance was determined using a paired t-test of the ΔCT (comparative threshold) values from 3–5 separate experimental preparations. N.D., not detectable. Values are means ± SE. ***P < 0.0001.

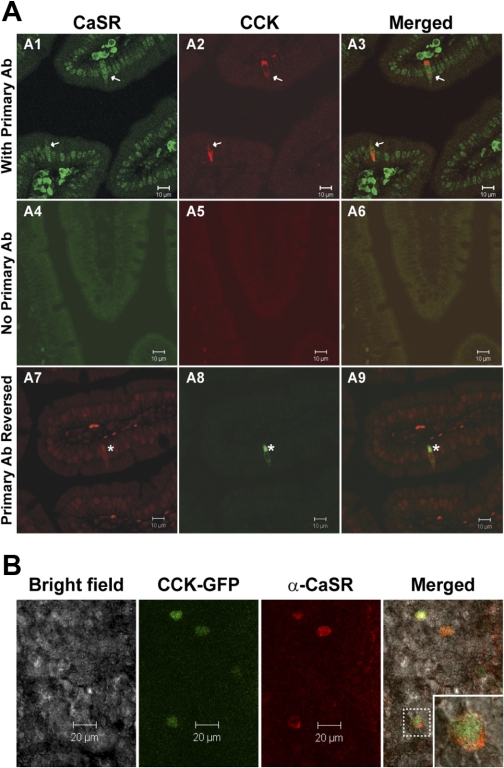

Given the differential gene expression for CaSR in CCK-eGFP cells compared with non-eGFP cells, the presence of CaSR protein was confirmed with immunofluorescent staining in antigen-retrieved, paraffin-embedded duodenal tissue (Fig. 3A) and on the cell surface of eGFP-positive cells from nonfixed and nonpermeabilized fresh duodenal villi (Fig. 3B) of CaSR+/+ PTH+/+ CCK-eGFP transgenic mice. For fixed tissue sections, all CCK immunoreactive cells were CaSR positive, with true CaSR immunoreactivity accepted as whole cell staining at all optical planes (Fig. 3, A1–A3). The same staining pattern was evident when the secondary antibody of the opposite emission spectra was reversed (Fig. 3, A7–A9). No secondary nonspecific staining was evident with exclusion of the primary antibody in both tissue sections (Fig. 3, A4–A6) and in fresh duodenal villi (data not shown).

Fig. 3.

Immunohistochemical colocalization of CaSR on CCK-expressing enteroendocrine cells. A: CCK-immunoreactive enteroendocrine cells express CaSR (arrows, asterisks) in paraffin-embedded duodenal tissue sections of CaSR+/+ PTH+/+ mice. CCK immunolabeling was concentrated on the basilar aspect of isolated cells. CaSR-specific immunostaining was distinguished from the high background nonspecific staining of nuclei within these sections by visualizing whole cell CaSR immunostaining throughout all microscopic focal planes within CCK-immunopositive cells. Primary antibody (Ab) was excluded in tissue sections represented in A4–A6. A1–A3, with primary Ab; A7–A9, primary Ab reversed. B: expression of CaSR in CCK-eGFP+ cells in fresh primary duodenal villi from CaSR+/+ CCK-eGFP transgenic mice. Inset: an enlarged CaSR-positive CCK-eGFP cell outlined in the villus demonstrating CaSR expression localized to the cell surface.

Intracellular Ca2+ flux in response to Phe is stereo selective and CaSR dependent in CCK-eGFP cells.

To examine whether CCK-eGFP cells express functional CaSR that can respond to amino acids in a stereoisomer-selective fashion, CCK-eGFP cells were tested for an intracellular Ca2+ response to l-Phe and d-Phe by confocal Ca2+ imaging (Fig. 4). In CaSR+/+ CCK-eGFP cells, l-Phe (20 mM, n = 11) significantly induced a time-dependent increase in relative FI of Quest Rhod4 (i.e., [Ca2+]i; P < 0.0001), which was significantly greater than the lower [Ca2+]i flux observed in response to d-Phe (20 mM; n = 9; P < 0.001; Fig. 4A, top graph). This differential response between l-Phe and d-Phe was eliminated in the absence of CaSR (n = 6 and n = 4, respectively; Fig. 4A, bottom graph). Two-way ANOVA post hoc analysis showed that the Ca2+ responses to both l-Phe and d-Phe was significantly greater in the CaSR+/+ CCK-eGFP cells compared with the CaSR−/− CCK-eGFP cells (P < 0.001 and P < 0.05, respectively; Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

l- or d-Phenylalanine (Phe)-stimulated changes in intracellular Ca2+ in CaSR+/+ and CaSR−/− CCK-eGFP cells. A: effect of l- or d-Phe (20 mM) on Ca2+ responses in CCK-eGFP cells. Representative time courses for changes in Quest Rhod4 fluorescence intensity after stimulation with either l-Phe (♦) or d-Phe (◊) in CaSR+/+ (top) and CaSR−/− (bottom) CCK-eGFP cells are shown. Arrow indicates time of stimulation. B: l- or d-Phe (20 mM) induced increases in intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) in CaSR+/+ (solid bars) vs. CaSR−/− (open bars) CCK-eGFP cells. Changes in [Ca2+]i in CCK-eGFP cells were analyzed as maximum %increase in the fluorescence intensity (FI) of Quest Rhod4 relative to the baseline. Values are means ± SE of maximum %increase. Maximum %increase was calculated as follows: (peak FI − basal FI)/basal FI × 100. *P < 0.05, d-Phe for CaSR+/+ (n = 9) vs. CaSR−/− (n = 4); ***P < 0.001, l-Phe (n = 11) vs. d-Phe (n = 9), CaSR+/+; ****P < 0.0001, l-Phe, CaSR+/+ (n = 11) vs. CaSR−/− (n = 6), or l-Phe (n = 11) vs. 0 mM vehicle control (n = 4).

Targeted deletion of CaSR inhibits CCK secretion in acutely isolated CCK-eGFP cells.

To evaluate the functional role of CaSR on CCK secretion, separately isolated CaSR+/+ PTH+/+ (CaSR+/+) and CaSR−/− PTH−/− (CaSR−/−) CCK-eGFP cells were subjected to various ligands, and CCK released in the supernatant was measured by radioimmunoassay. Baseline secretion at normal physiological calcium (1.26 mM) concentrations was not significantly different between CaSR+/+ and CaSR−/− CCK-eGFP cells, measured as 5.8 ± 0.9 and 6.0 ± 0.9% of total CCK content, respectively. In CaSR+/+ CCK-eGFP cells, l-Phe (30 mM) significantly increased CCK secretion (P < 0.05; Fig. 5A). Moreover, additional extracellular calcium (superphysiological at 2.5 mM) enhanced this response by approximately twofold. In contrast, l-Phe did not stimulate CCK secretion in CaSR−/− CCK-eGFP cells at both calcium concentrations (Fig. 5B); however, a trend toward a 20–30% decrease in CCK secretion, relative to basal, was evident. Superphysiological calcium alone caused a slight, but insignificant, increase in CCK secretion in CaSR+/+ CCK-eGFP cells. Similar to what was observed with l-Phe, a trend toward reduced secretion was also observed in CaSR−/− CCK-eGFP cells in response to superphysiological calcium. Tryptone (1%) elicited a significant increase in CCK secretion in CaSR+/+ CCK-eGFP cells (P < 0.05), but not in the CaSR−/− CCK-eGFP cells. Although not significantly different from baseline, d-Phe caused a trend toward an increase in CCK secretion in both CaSR+/+ and CaSR−/− CCK-eGFP cells. Both cell populations were equally and significantly responsive to KCl (P < 0.01), which was used to assess intra-assay cell viability and secretory potential.

Fig. 5.

Effect of CaSR expression on stimulated secretion of CCK from isolated I cells. CCK secretion was from sorted CaSR+/+ (solid bars; A) and CaSR−/− (open bars; B) CCK-eGFP cells in response to a 30-min incubation with l-Phe (30 mM) alone and with additional extracellular Ca2+ (2.5 mM), 2.5 mM Ca2+ alone, d-Phe (30 mM), 1% tryptone, and KCl (50 mM). CCK secreted in the supernatant was measured by RIA. Results are presented as %change (means ± SE) from baseline CCK secretion in Hank's balanced salt solution supplemented with 10 mM HEPES (HHBSS) alone. N = 6–9 separate cell preparations for all treatments, with each condition performed and sampled in triplicate. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01, relative to baseline secretion within each genotype.

Targeted deletion of CaSR abolishes intracellular Ca2+ flux and negatively inhibits CCK secretion in response to cinacalcet in CCK-eGFP cells.

Type II calcimimetic, cinacalcet, was used to further assess whether the intracellular calcium response and CCK secretion in CCK-eGFP cells was CaSR specific. A 1,000 nM dose has been shown previously to allosterically activate the CaSR (29). The same dose induced an intracellular Ca2+ response in CasR+/+ CCK-eGFP cells (n = 16) that was significantly greater than the response observed in CasR−/− CCK-eGFP cells (n = 10; P < 0.0001; Fig. 6, A and B). Baseline CCK secretion with a 0.05% DMSO-HHBSS vehicle, relative to total CCK content, was similar in both CaSR WT (6.4 ± 0.8%, n = 6) and KO (6.6 ± 0.7%, n = 5) CCK-eGFP cells. A modest trend toward increased CCK secretion was observed in CaSR+/+ CCK-eGFP cells given 1,000 nM cinacalcet, while the same dose caused a significant decrease in CCK secretion (Fig. 6C; P < 0.05). Additionally, both cell types were equally responsive to 50 mM KCl (data not shown).

Fig. 6.

Effect of cinacalcet on intracellular Ca2+ flux and CCK secretion from I cells in the presence or absence of CaSR. A: representative time courses of changes in [Ca2+]i in Quest Rhod4-loaded CCK-eGFP cells stimulated with cinacalcet (1 μM). ♦, CaSR+/+; ◊, CaSR−/−; arrow, time of stimulation. B: mean maximum %increase (±SE) in the FI of Quest Rhod4 relative to the baseline [(peak FI − basal FI)/basal FI × 100] in CasR+/+ (n = 16) vs. CasR−/− (n = 10) CCK-eGFP cells after stimulation with cinacalcet, 1 μM. ****P < 0.0001 with unpaired t-test. C: CCK released in the supernatant of sorted CaSR+/+ (solid bar) and CaSR−/− (open bar) CCK-eGFP cells incubated with cinacalcet (1 μM). Results are presented as %change (means ± SE) from baseline secretion in 0.05% DMSO-HHBSS vehicle alone. N = 5–7 separate cell populations with each condition performed and sampled in triplicate. *P < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we provide evidence that the extracellular CaSR is expressed on native intestinal I cells at a gene and protein level. Isolation of native I cells from CCK-eGFP mice or CCK-eGFP mice bred to CaSR PTH double homozygous KO mice enabled evaluation of the CaSR for its putative role in directly mediating CCK secretion in response to l-Phe. Our studies revealed that CCK-eGFP cell activation is CaSR dependent and that CCK secretion in response to direct stimulation with l-Phe is enhanced in the presence of superphysiological extracellular calcium ([Ca2+]o) levels, implicating that the CaSR serves a nutrient-sensing function to mediate aromatic amino acid-induced CCK secretion in the native intestinal I cell.

Aside from calcium-regulating tissue types, the CaSR is also found in pancreatic β-cells (41) and gastrointestinal endocrine cells, including gastrin secreting G cells in the stomach (34) and chromogranin A-staining cells throughout the intestine (39). CaSR transcript is also evident in the STC-1 cell line (16), suggesting that CaSR expression is specific to neuroendocrine cells. Conflicting evidence localizing CaSR protein throughout the basilar aspect of absorptive duodenal epithelial cells exists (7). However, our qPCR findings in isolated CCK-eGFP cells and immunochemical staining confirm that CaSR is expressed in duodenal CCK-secreting enteroendocrine cells and not absorptive epithelial cells. We cannot rule out, however, the possibility that other enteroendocrine cell types express the CaSR.

We also evaluated isolated CCK-eGFP cells for transcripts of the umami taste receptor, since taste receptor signaling components have been found within isolated cells of the intestinal epithelium (3) and in the STC-1 cell line (13). This heterodimeric complex of G protein-coupled receptors T1R1 and T1R3, originally described in taste buds of the tongue (28), presented as a potential alternative amino acid receptor to the CaSR in the enteroendocrine cell. However, since T1R1 subunit transcripts were undetectable in our samples, we considered it unlikely that this taste receptor is involved in amino acid detection by the native I cell.

Given that aromatic amino acids allosterically activate the CaSR and that [Ca2+]o is essential for hormone secretion, the CaSR is a reasonable candidate for mediating l-Phe-induced CCK secretion in the native I cell. Indeed, [Ca2+]o and l-Phe synergistically increase intracellular calcium flux and CCK secretion in the STC-1 cell (16), mirroring the pharmacological profile of the CaSR (12). And, in our isolated CCK-eGFP cells, l-Phe directly caused a significant increase in intracellular calcium and CCK secretion, the secretion of which was enhanced in the presence of superphysiological [Ca2+]o levels. Calcium is a primary agonist for the CaSR, whereas l-Phe requires the presence of calcium to allosterically increase CaSR sensitivity to [Ca2+]o (12). Interestingly, superphysiological [Ca2+]o levels alone failed to significantly increase CCK secretion in isolated CCK-eGFP cells. It is well established that extracellular calcium influx by way of L-type calcium channels is required for secretion in response to various nutrients, including l-Phe, in both the STC-1 cell line and in intestinal mucosal cells (21, 25, 30, 38). Removal of [Ca2+]o with EGTA reduces CCK secretion in response to bombesin (40), peptone, and peptidomimetic antibiotics (30) in STC-1 cells, as well as in perifused rat intestinal mucosal cells in response to monitor peptide (4), bombesin (38), and the calcium ionophore A23187 (4). However, unlike the parathyroid cell (5) or even the G cell (6), luminal calcium is not a recognized secretagogue for the I cell. Therefore, although [Ca2+]o is a requirement for secretory responses to various secretagogues, it alone is not sufficient enough to evoke hormone secretion from the native I cell.

Through interactions with different G proteins, other membrane proteins, and cytoskeletal elements, the CaSR can transduce various signals to regulate specific cellular functions, ranging from cell division and differentiation to hormone secretion (18). [Ca2+]o, aromatic amino acids, and calcimimetics bind different sites of the CaSR (26, 27, 46, 47), which may influence which signaling pathway is activated. Indeed, [Ca2+]o and l-Phe activation of the CaSR results in transduction of different signaling pathways and intracellular Ca2+ oscillation patterns (35, 36). [Ca2+]o activation increases inositol trisphosphate production and intracellular Ca2+ flux through a Gq signaling pathway, while l-Phe targets a G12/13 and the Rho ATPase pathway to allow [Ca2+]o entry via the cation channel canonical transient receptor potential 1 (35, 36). The observation that l-Phe, and not [Ca2+]o, increased hormone secretion, and that the type II allosteric activator cinacalcet trends but does not significantly increase CCK secretion, despite an increase in [Ca2+]i in isolated CCK-eGFP cells, suggests that l-Phe specifically directs a dominant signaling pathway potentiating hormone secretion. Allosteric activation of the CaSR by l-Phe would also activate [Ca2+]o-mediated signaling, and the interaction of both pathways may explain the secretory response to l-Phe in the presence of [Ca2+]o and the enhancement of hormone secretion with additional [Ca2+]o. Therefore, the CaSR may specifically function in the I cell as a predominate aromatic amino acid sensor, mediating hormone secretion in response to l-Phe.

To ensure that the enhanced secretory response to l-Phe in the presence of additional [Ca2+]o was specific to the CaSR rather than through an alternative nutrient sensor, we measured CCK secretion in CCK-eGFP cells isolated from CaSR null animals, expecting that targeted deletion of the CaSR would render the native I cell unresponsive to l-Phe. Absence of the CaSR not only prevented CCK secretion in response to [Ca2+]o and l-Phe, but a trend toward a reduction in secretion, below that of baseline, was observed. This response was specific to allosteric activators or agonists of CaSR and not to a more heterogeneous protein hydrolysate mixture or to the weaker d-Phe isomer (12), whose modest effect is likely nonspecific to CaSR activation. Hormone secretion in response to CaSR-independent secretagogue KCl was also unaffected in the absence of the CaSR. Moreover, a significant reduction in secretion relative to baseline was observed in CaSR KO CCK-eGFP cells given type II calcimimetic cinacalcet. The specificity of this change in secretory behavior in response to CaSR ligands in the absence of CaSR further supports a role for CaSR in CCK secretion. In addition, a receptor-mediated inhibitory pathway appears to have been unmasked in the absence of CaSR expression that clearly reduces secretory function to CaSR-specific ligands.

The mechanism by which CaSR agonists and allosteric activators cause this reduction in secretion in CaSR KO CCK-eGFP cells is unclear, but it is unlikely that the effect is due to decreased cellular excitability. ATP-sensitive K+ channels regulating basal membrane potential (20, 23) can be affected by CaSR. However, there was no difference in basal secretion between CaSR WT and KO CCK-eGFP cells. Rather, another mechanism that binds similar ligands may be involved. A CaSR splice variant that lacks exon 5, which is believed to encode the [Ca2+]o binding region of the NH2-terminus, has previously been shown to be expressed within epidermal cells of the CaSR−/− mice used in our laboratory's studies (31). The CaSR−/− mice contain a neomycin cassette within exon 5, preventing functional expression of full-length CaSR (17), but the splice variant appears to remain intact in various tissues (31). Coexpression of the CaSR splice variant reduces downstream intracellular calcium flux and inositol trisphosphate production in response to [Ca2+]o in human keratinocytes (32). Further studies would be important and necessary to evaluate the expression of the CaSR splice variant in the intestinal I cell, and whether this splice variant is driving an inhibitory signaling pathway, reducing hormone secretion in response to CaSR-mediated secretagogues.

It is also possible that the CaSR is coupled to other ion channels regulating intracellular Ca2+ entry. Besides the cation channel canonical transient receptor potential 1 (35, 36), thapsigargin sensitive nonselective cation channels have also been linked to CaSR activation and membrane depolarization in several neuronal cell types, such as murine hippocampal pyramidal cells, rat hippocampal cells, CaSR transfected human embryonic kidney-293 cells, and presynaptic neurons (44–45), as well as in insulin secreting β-cells and gastrin secreting G cells (42). Studies in murine neocortical neurons and human astrocytoma cell lines suggest a regulatory role of CaSR on calcium-dependent K+ channels influencing membrane excitability (8, 43). Whether coupling of either of these channels to CaSR, or perhaps L-type calcium channels that drive [Ca2+]o entry into the cell (22), has an effect on CCK secretion remains to be elucidated.

Tryptone significantly increased CCK secretion in CaSR WT CCK-eGFP cells, but, in the absence of CaSR, tryptone's stimulatory effect is no longer significant from baseline. Being an enzymatic digest of casein, tryptone contains a heterogeneous mixture of single amino acids and peptides. By genetically deleting the CaSR, any stimulatory effect from the amino acid component of tryptone would be lost. However, unlike what was observed in response to l-Phe, [Ca2+]o, and cinacalcet, tryptone continues to display an upward trend in CCK secretion. This may be due to the presence of other membrane protein receptors that sense peptides. Such candidates include the peptone receptor GPR92/93 (10) and the proton-coupled oligopeptide transporter PepT1 (24), whose gene expression was demonstrated in the initial qPCR screening of CCK-eGFP cells. However, given that neighboring enterocytes also possess GPR92 (9) and PepT1 (37), further studies are required to determine whether these candidates have a direct, rather than an indirect, effect on hormone secretion in the native cell.

Given the present findings, we suggest that the CaSR offers a functional role for cellular activity in response to l-Phe. The mechanism requires further study, but we hypothesize that the CaSR modulates signaling pathways that open calcium channels, allowing [Ca2+]o entry and intracellular Ca2+ influx leading to CCK secretion. In the absence or antagonism of CaSR, a receptor-mediated inhibitory pathway (perhaps mediated by the CaSR splice variant) is activated to prevent secretory vesicle release, resulting in the inhibition of hormone secretion. This inhibitory pathway may also explain the negative trend that is seen in response to CaSR-specific ligands in the CaSR−/− CCK-eGFP cells. It is becoming increasingly apparent that multiple modalities for the detection of dietary protein digestive products exist, illustrating the complexity of nutrient sensing in enteroendocrine cells.

GRANTS

This work was partially supported by the Veterinary Scientists Training Program, University of California, Davis School of Veterinary Medicine (A. P. Liou) and by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grant DK-41004 (H. E. Raybould).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

REFERENCES

- 1. Anika SM, Houpt TR, Houpt KA. Satiety elicited by cholecystokinin in intact and vagotomized rats. Physiol Behav 19: 761– 766, 1977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ballinger AB, Clark ML. l-Phenylalanine releases cholecystokinin (CCK) and is associated with reduced food intake in humans: evidence for a physiological role of CCK in control of eating. Metabolism 43: 735– 738, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bezencon C, le Coutre J, Damak S. Taste-signaling proteins are coexpressed in solitary intestinal epithelial cells. Chem Senses 32: 41– 49, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bouras EP, Misukonis MA, Liddle RA. Role of calcium in monitor peptide-stimulated cholecystokinin release from perifused intestinal cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 262: G791– G796, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brown EM, Gamba G, Riccardi D, Lombardi M, Butters R, Kifor O, Sun A, Hediger MA, Lytton J, Hebert SC. Cloning and characterization of an extracellular Ca(2+)-sensing receptor from bovine parathyroid. Nature 366: 575– 580, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Buchan AM, Squires PE, Ring M, Meloche RM. Mechanism of action of the calcium-sensing receptor in human antral gastrin cells. Gastroenterology 120: 1128– 1139, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chattopadhyay N, Cheng I, Rogers K, Riccardi D, Hall A, Diaz R, Hebert SC, Soybel DI, Brown EM. Identification and localization of extracellular Ca2+-sensing receptor in rat intestine. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 274: G122– G130, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chattopadhyay N, Ye CP, Yamaguchi T, Vassilev PM, Brown EM. Evidence for extracellular calcium-sensing receptor mediated opening of an outward K+ channel in a human astrocytoma cell line (U87). Glia 26: 64– 72, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Choi S, Lee M, Shiu AL, Yo SJ, Aponte GW. Identification of a protein hydrolysate responsive G protein-coupled receptor in enterocytes. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 292: G98– G112, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Choi S, Lee M, Shiu AL, Yo SJ, Hallden G, Aponte GW. GPR93 activation by protein hydrolysate induces CCK transcription and secretion in STC-1 cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 292: G1366– G1375, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Conigrave AD, Brown EM. Taste receptors in the gastrointestinal tract. II. l-Amino acid sensing by calcium-sensing receptors: implications for GI physiology. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 291: G753– G761, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Conigrave AD, Quinn SJ, Brown EM. l-Amino acid sensing by the extracellular Ca2+-sensing receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97: 4814– 4819, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dyer J, Salmon KS, Zibrik L, Shirazi-Beechey SP. Expression of sweet taste receptors of the T1R family in the intestinal tract and enteroendocrine cells. Biochem Soc Trans 33: 302– 305, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gibbs J, Falasco JD, McHugh PR. Cholecystokinin-decreased food intake in rhesus monkeys. Am J Physiol 230: 15– 18, 1976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Goebel SU, Peghini PL, Goldsmith PK, Spiegel AM, Gibril F, Raffeld M, Jensen RT, Serrano J. Expression of the calcium-sensing receptor in gastrinomas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 85: 4131– 4137, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hira T, Nakajima S, Eto Y, Hara H. Calcium-sensing receptor mediates phenylalanine-induced cholecystokinin secretion in enteroendocrine STC-1 cells. FEBS J 275: 4620– 4626, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ho C, Conner DA, Pollak MR, Ladd DJ, Kifor O, Warren HB, Brown EM, Seidman JG, Seidman CE. A mouse model of human familial hypocalciuric hypercalcemia and neonatal severe hyperparathyroidism. Nat Genet 11: 389– 394, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Huang C, Miller RT. The calcium-sensing receptor and its interacting proteins. J Cell Mol Med 11: 923– 934, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kos CH, Karaplis AC, Peng JB, Hediger MA, Goltzman D, Mohammad KS, Guise TA, Pollak MR. The calcium-sensing receptor is required for normal calcium homeostasis independent of parathyroid hormone. J Clin Invest 111: 1021– 1028, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mangel AW, Prpic V, Snow ND, Basavappa S, Hurst LJ, Sharara AI, Liddle RA. Regulation of cholecystokinin secretion by ATP-sensitive potassium channels. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 267: G595– G600, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mangel AW, Prpic V, Wong H, Basavappa S, Hurst LJ, Scott L, Garman RL, Hayes JS, Sharara AI, Snow ND, Walsh JH, Liddle RA. Phenylalanine-stimulated secretion of cholecystokinin is calcium dependent. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 268: G90– G94, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mangel AW, Scott L, Liddle RA. Depolarization-stimulated cholecystokinin secretion is mediated by L-type calcium channels in STC-1 cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 270: G287– G290, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mangel AW, Snow ND, Misukonis MA, Basavappa S, Middleton JP, Fitz JG, Liddle RA. Calcium-dependent regulation of cholecystokinin secretion and potassium currents in STC-1 cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 264: G1031– G1036, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Matsumura K, Miki T, Jhomori T, Gonoi T, Seino S. Possible role of PEPT1 in gastrointestinal hormone secretion. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 336: 1028– 1032, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. McLaughlin JT, Lomax RB, Hall L, Dockray GJ, Thompson DG, Warhurst G. Fatty acids stimulate cholecystokinin secretion via an acyl chain length-specific, Ca2+-dependent mechanism in the enteroendocrine cell line STC-1. J Physiol 513: 11– 18, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Miedlich SU, Gama L, Seuwen K, Wolf RM, Breitwieser GE. Homology modeling of the transmembrane domain of the human calcium sensing receptor and localization of an allosteric binding site. J Biol Chem 279: 7254– 7263, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mun HC, Franks AH, Culverston EL, Krapcho K, Nemeth EF, Conigrave AD. The Venus Fly Trap domain of the extracellular Ca2+-sensing receptor is required for l-amino acid sensing. J Biol Chem 279: 51739– 51744, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Nelson G, Chandrashekar J, Hoon MA, Feng L, Zhao G, Ryba NJ, Zuker CS. An amino-acid taste receptor. Nature 416: 199– 202, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Nemeth EF, Heaton WH, Miller M, Fox J, Balandrin MF, Van Wagenen BC, Colloton M, Karbon W, Scherrer J, Shatzen E, Rishton G, Scully S, Qi M, Harris R, Lacey D, Martin D. Pharmacodynamics of the type II calcimimetic compound cinacalcet HCl. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 308: 627– 635, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nemoz-Gaillard E, Bernard C, Abello J, Cordier-Bussat M, Chayvialle JA, Cuber JC. Regulation of cholecystokinin secretion by peptones and peptidomimetic antibiotics in STC-1 cells. Endocrinology 139: 932– 938, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Oda Y, Tu CL, Chang W, Crumrine D, Komuves L, Mauro T, Elias PM, Bikle DD. The calcium sensing receptor and its alternatively spliced form in murine epidermal differentiation. J Biol Chem 275: 1183– 1190, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Oda Y, Tu CL, Pillai S, Bikle DD. The calcium sensing receptor and its alternatively spliced form in keratinocyte differentiation. J Biol Chem 273: 23344– 23352, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rasschaert J, Malaisse WJ. Expression of the calcium-sensing receptor in pancreatic islet B-cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 264: 615– 618, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ray JM, Squires PE, Curtis SB, Meloche MR, Buchan AM. Expression of the calcium-sensing receptor on human antral gastrin cells in culture. J Clin Invest 99: 2328– 2333, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rey O, Young SH, Papazyan R, Shapiro MS, Rozengurt E. Requirement of the TRPC1 cation channel in the generation of transient Ca2+ oscillations by the calcium-sensing receptor. J Biol Chem 281: 38730– 38737, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rey O, Young SH, Yuan J, Slice L, Rozengurt E. Amino acid-stimulated Ca2+ oscillations produced by the Ca2+-sensing receptor are mediated by a phospholipase C/inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate-independent pathway that requires G12, Rho, filamin-A, and the actin cytoskeleton. J Biol Chem 280: 22875– 22882, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sai Y, Tamai I, Sumikawa H, Hayashi K, Nakanishi T, Amano O, Numata M, Iseki S, Tsuji A. Immunolocalization and pharmacological relevance of oligopeptide transporter PepT1 in intestinal absorption of beta-lactam antibiotics. FEBS Lett 392: 25– 29, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sharara AI, Bouras EP, Misukonis MA, Liddle RA. Evidence for indirect dietary regulation of cholecystokinin release in rats. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 265: G107– G112, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sheinin Y, Kallay E, Wrba F, Kriwanek S, Peterlik M, Cross HS. Immunocytochemical localization of the extracellular calcium-sensing receptor in normal and malignant human large intestinal mucosa. J Histochem Cytochem 48: 595– 602, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Snow ND, Prpic V, Mangel AW, Sharara AI, McVey DC, Hurst LJ, Vigna SR, Liddle RA. Regulation of cholecystokinin secretion by bombesin in STC-1 cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 267: G859– G865, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Squires PE, Harris TE, Persaud SJ, Curtis SB, Buchan AM, Jones PM. The extracellular calcium-sensing receptor on human beta-cells negatively modulates insulin secretion. Diabetes 49: 409– 417, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Straub SG, Kornreich B, Oswald RE, Nemeth EF, Sharp GW. The calcimimetic R-467 potentiates insulin secretion in pancreatic beta cells by activation of a nonspecific cation channel. J Biol Chem 275: 18777– 18784, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Vassilev PM, Ho-Pao CL, Kanazirska MP, Ye C, Hong K, Seidman CE, Seidman JG, Brown EM. Cao-sensing receptor (CaR)-mediated activation of K+ channels is blunted in CaR gene-deficient mouse neurons. Neuroreport 8: 1411– 1416, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ye C, Ho-Pao CL, Kanazirska M, Quinn S, Seidman CE, Seidman JG, Brown EM, Vassilev PM. Deficient cation channel regulation in neurons from mice with targeted disruption of the extracellular Ca2+-sensing receptor gene. Brain Res Bull 44: 75– 84, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ye C, Kanazirska M, Quinn S, Brown EM, Vassilev PM. Modulation by polycationic Ca2+-sensing receptor agonists of nonselective cation channels in rat hippocampal neurons. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 224: 271– 280, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Zhang Z, Jiang Y, Quinn SJ, Krapcho K, Nemeth EF, Bai M. l-Phenylalanine and NPS R-467 synergistically potentiate the function of the extracellular calcium-sensing receptor through distinct sites. J Biol Chem 277: 33736– 33741, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Zhang Z, Qiu W, Quinn SJ, Conigrave AD, Brown EM, Bai M. Three adjacent serines in the extracellular domains of the CaR are required for l-amino acid-mediated potentiation of receptor function. J Biol Chem 277: 33727– 33735, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]