Abstract

It is well known that sodium reabsorption and aldosterone play important roles in potassium secretion by the aldosterone-sensitive distal nephron. Sodium- and aldosterone-independent mechanisms also exist. This review focuses on some recent studies that provide novel insights into the sodium- and aldosterone-independent potassium secretion by the aldosterone-sensitive distal nephron. In addition, we discuss a study reporting on the regulation of the mammalian potassium kidney channel ROMK by intracellular and extracellular magnesium, which may be important in the pathogenesis of persistent hypokalemia in patients with concomitant potassium and magnesium deficiency. We also discuss outstanding questions and propose working models for future investigation.

Keywords: aldosterone, intercalated cell, maxi-K, ROMK, WNK1

the aldosterone-sensitive distal nephron, comprising the late distal convoluted tubule, the connecting tubule, the cortical collecting duct, and to a lesser extent the medullary collecting duct, determines the final urinary potassium content and therefore regulates total body potassium homeostasis (41). A major mechanism for potassium secretion in this part of the nephron is the generation of a lumen-negative potential by the reabsorption of sodium through the apical epithelial sodium channel (ENaC). Together with the activity of the basolateral Na-K-ATPase, which transports potassium into tubular epithelial cells against a concentration gradient, sodium reabsorption through ENaC generates the electrochemical gradient for potassium secretion. Aldosterone stimulates this pathway by increasing the activity and density of ENaC and Na-K-ATPase. However, while elevation in aldosterone is necessary for maximal potassium excretion, there are clearly aldosterone-independent mechanisms for potassium excretion (12, 26, 63, 78, 81).

In this review, we will discuss recent studies that provide new, exciting insights into mechanisms of sodium-independent potassium secretion that allow the kidney to upregulate potassium secretion in the setting of high dietary potassium intake. In addition, the kidney responds to a high-potassium diet by increasing distal flow and sodium delivery, both of which have potent effects on potassium secretion (20, 21, 31, 39, 40). This occurs in part due to the shifting of sodium reabsorption from an electroneutral Na-(K)-Cl reabsorption in the thick ascending limb of the loop of Henle and the distal convoluted tubule via the Na+-K+-2Cl− (NKCC2) or Na+-Cl− (NCC) cotransporters, respectively, to an electrogenic sodium reabsorption in the aldosterone-sensitive distal nephron, in which sodium reabsorption through ENaC is exchanged with potassium secretion. We will discuss recent studies providing novel regulatory mechanisms by which this may occur. Space restrictions prevent a comprehensive review of all studies devoted to distal potassium handling; the reader is referred to recent reviews that discuss other aspects of this process (57, 73, 75, 80).

Sodium-Independent Potassium Secretion

A recent paper by Frindt and Palmer (15) provides new insights into the relative role of sodium-independent potassium secretion. Rats were administered acute intravenous infusions of amiloride to achieve tubular concentrations sufficient to block >98% of apical ENaC. Under control conditions, this completely abolished potassium secretion. As rats were fed increasing amounts of potassium, however, an ENaC-independent (i.e., amiloride-insensitive) potassium secretory pathway was revealed. In fact, a relatively modest increase in potassium ingestion, from 0.6 to 0.9%, was sufficient to increase sodium-independent potassium secretion (15). These results are consistent with the findings of Muto et al. (42), in which removal of luminal sodium from the perfusate of isolated perfused rabbit cortical collecting duct decreased, but did not abolish, potassium secretion.

What are the mechanisms for sodium-independent potassium secretion? Frindt and Palmer (15) discussed several possible mechanisms. One of these is the above-mentioned report by Muto et al. (42) showing that basolateral Na+/H+ exchangers operate along with Na-K-ATPase to recycle sodium and allow potassium secretion in the absence of luminal sodium. This mechanism presumably operates in principal cells. Additional possibilities for sodium-independent potassium secretion have emerged from subsequently published papers. This review focuses on recent studies implicating the role of intercalated cells in this process.

Role of intercalated cells: BK, Kv1.3, and chloride channels.

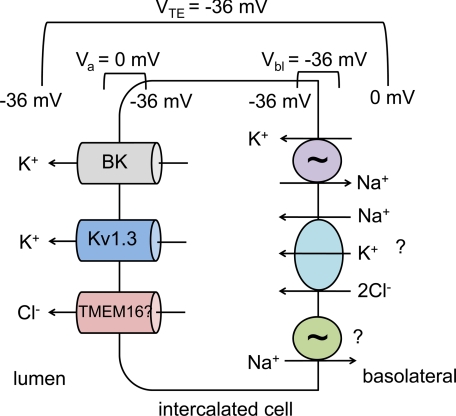

One possibility is that transcellular potassium secretion occurs through intercalated cells, in which apically located potassium channels are electrically coupled to apical chloride channels (see Fig. 1). Palmer and Frindt have estimated the apical membrane potential of intercalated cells to be ∼0 mV (50). In this case, the electric driving force for potassium secretion is greater than across the apical membrane of the principal cell, in which the membrane potential of approximately −80 mV must be compensated for by the large transepithelial potential generated by sodium reabsorption through ENaC. In addition, the relatively depolarized membrane potential of the intercalated cells increases the open probability of voltage-gated potassium channels. One of these, the large-conductance, calcium-activated potassium channel, known as BK or maxi-K, has been appreciated to play a role in renal potassium secretion for some time, and in vivo studies have confirmed its role in renal potassium excretion (2, 22, 52, 53, 56). Although there is some controversy regarding whether BK is acting in principal cells, intercalated cells, or both, it is clearly found at high density in intercalated cells in both the connecting tubule and the cortical collecting duct of the rat (13, 47, 50), and mRNAs of BK channel subunits are upregulated in intercalated cells of rabbits on a high-potassium diet (43). Interestingly, iberiotoxin-inhibitable, BK-dependent potassium secretion in the rabbit cortical collecting duct was decreased but not abolished under conditions of no luminal sodium (42). This suggests that BK-dependent potassium secretion can also occur by both sodium-dependent and -independent mechanisms.

Fig. 1.

Model of intercalated cell potassium secretion. Due to a large basolateral chloride conductance (not shown), the basolateral membrane potential (Vbl) of the intercalated cell is close to the equilibrium potential for chloride, approximately −36 mV. Due to electrogenic sodium reabsorption through the epithelial sodium channel (ENaC) in neighboring principal cells (not shown), a transepithelial potential (VTE) is generated. If this is about the same as Vbl, the apical membrane potential (Va) of the intercalated cell will be ∼0 mV (see Ref. 50 for a more detailed discussion). This relatively depolarized Va results in a higher open probability for the voltage-gated potassium channels BK and Kv1.3 and provides a strong electric driving force for potassium secretion. By coupling potassium secretion to chloride secretion, a sodium-independent component of potassium secretion can be achieved. An apical chloride channel has yet to be identified, but an attractive hypothesis is that a member of the voltage- and calcium-dependent TMEM16 family could provide this function. On the basolateral side, potassium uptake may occur through the Na-K-ATPase, but because this is present at only low levels in intercalated cells, additional uptake may occur through Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransporter isoform 1 (NKCC1). If Na-K-ATPase is limiting, the cotransported sodium could be recycled either through the ouabain-insensitive Na-ATPase, or through other unidentified mechanisms, such as a Na-HCO3− cotransporter (not shown).

A second voltage-gated potassium channel that is expressed on the apical surface of intercalated cells, Kv1.3, has recently been described by Carrisoza-Gaytan et al. (6). In rats fed a high-potassium diet, apical expression of Kv1.3 is seen in α-intercalated cells, and decreased potassium secretion is observed with luminal perfusion of margatoxin, a Kv1.3 inhibitor, in isolated cortical collecting ducts from these rats (6). Further experiments are needed to better define the importance of this channel. For example, can Kv1.3 currents be identified in intercalated cells in which BK (which may otherwise mask the Kv1.3 currents) has been inhibited? Can a role for Kv1.3 be uncovered in tubules from ROMK knockout mice treated with iberiotoxin (a BK inhibitor)? A previous study showed that in these mice, potassium secretion in the late distal tubule was abolished, suggesting that ROMK and BK comprise the entire exit pathway for apical potassium secretion (2). However, these mice were not studied under high-potassium conditions, and it is also possible that Kv1.3 may play a role in tubular sites that were not studied in these micropuncture experiments.

While the depolarized apical membrane potential of intercalated cells provides an attractive explanation for the activity of BK and Kv1.3 (which are relatively quiescent in hyperpolarized membrane potentials), it does not explain the potential sodium independence of this process. Potassium secretion across the apical membrane hyperpolarizes the membrane potential and diminishes the driving force for further secretion. Sodium reabsorption via ENaC provides a sustained driving force for potassium secretion in principal cells. One hypothesis for sodium-independent potassium secretion in intercalated cells lacking ENaC is that apical potassium secretion is electrically coupled to apical chloride secretion. In both rabbits (77) and rats (69), decreasing tubular luminal chloride concentration increases potassium secretion. A study by Fernandez et al. (11) suggests that an apical chloride channel may be present on the surface of intercalated cells. Such a channel has not been electrophysiologically characterized in native tubules but has been studied in a renal cultured cell line derived from cortical collecting duct with intercalated cell characteristics (9, 33, 61). The molecular identity of this channel is unknown. Intriguingly, a family of calcium-activated chloride channels, the TMEM16 proteins, has recently been identified (18). Like BK, these channels are both calcium sensitive and voltage dependent and thus could conceivably be activated under the same conditions as BK. TMEM16 channels have been recently shown to play a role in epithelial ion transport (10, 30, 46, 60). mRNA for some family members has been demonstrated in the mouse kidney (60), but these channels have not otherwise been studied in the kidney.

One problem with the hypothesis that transepithelial potassium secretion occurs via intercalated cells, however, is that the mechanism for basolateral potassium uptake is unclear. Studies measuring ouabain-sensitive current (50), or using electron microprobe (59) or energy-dispersive X-ray microanalysis (4) of freeze-dried cryosections, are consistent with only low levels of Na-K-ATPase activity in intercalated cells compared with principal cells. Whether Na-K-ATPase activity increases in intercalated cells in animals on a high-potassium diet has not been studied, although by immunohistochemistry expression of Na-K-ATPase in intercalated cells of mice fed a high-potassium diet is low (27). An interesting possibility is that Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransporter isoform 1 (NKCC1) could serve in this role. A recent abstract reports that iberiotoxin-sensitive, flow-stimulated potassium secretion in rabbit isolated perfused cortical collecting duct was abolished by the basolateral application of bumetanide or removal of basolateral chloride (34). This is similar to the physiology of the distal colon, in which potassium secretion is thought to occur via basolateral uptake of potassium by NKCC1, followed by apical secretion through BK channels (62). NKCC1 is expressed on the basolateral membrane of rat intercalated cells in the medulla (19). Whether it is expressed at significant levels on the basolateral membrane of intercalated cells in the cortical collecting duct or connecting tubule under high-potassium conditions is unknown. Nonetheless, it is intriguing that knockout mice lacking NKCC1 have higher serum potassium concentrations than wild-type controls (71). A demonstration that sodium-independent potassium excretion is impaired in these mice, and that potassium secretion in isolated perfused cortical collecting tubules is decreased, would provide further support for a role for NKCC1. However, given the low intercalated cell Na-K-ATPase activity, this raises the question of how the sodium cotransported with potassium would be recycled across the basolateral membrane. One possibility is through the ouabain-insensitive Na-ATPase. In a recent study, this activity was observed in intercalated cell-like MDCK C11 cells at levels similar to those seen for the ouabain-sensitive Na-K-ATPase found in principal cell-like MDCK C7 cells (58). The molecular identity of this ATPase is unknown. Clearly, further studies are needed to clarify the molecular mechanisms by which intercalated cells may be involved in potassium secretion; Fig. 1 provides a hypothetical model that may serve as a basis for future experiments.

Role for BK in intercalated cell shrinkage and modulation of fluid dynamics.

Holtzclaw et al. (28) propose an entirely different mechanism by which BK in intercalated cells may enhance potassium secretion. First, studying MDCK C11 cells, which like murine intercalated cells express the BK-α and -β4 subunits, they found that shear stress results in the loss of intracellular cations and cell shrinkage in a BK-dependent process. This is explained by potassium efflux through the apical membrane under conditions of shear stress, which activates BK; due to the low levels of basolateral Na-K-ATPase, the cells cannot restore intracellular potassium and cell volume (28). Next, the authors examined a role for this process in vivo by studying BK-β4 knockout mice. When fed a high-potassium diet, wild-type mice had increased urinary flow. While Na-K-ATPase expression in principal cells was upregulated under these conditions, immunostaining was barely detectable in intercalated cells. Consistent with the authors' findings in cultured cells, intercalated cells in the potassium-adapted wild-type animals underwent shrinkage, presumably in response to BK activation by increased distal flow, thereby increasing the cross-sectional area of the connecting tubule and collecting duct. In contrast, in the β4 knockout mice, the intercalated cells did not shrink, and the cross-sectional areas of the connecting tubule and collecting duct increased to a lesser degree than seen in wild-type mice. The authors propose that this could alter fluid dynamics in the distal tubule such that potassium secretion is impaired, thereby explaining the increased plasma potassium concentration and decreased fractional excretion of potassium observed in the knockout mice (27).

Coordinated Roles of NCC and ROMK in Regulation of Potassium Secretion

Effects of dietary potassium on NCC and ROMK.

It has long been appreciated that an acute infusion of potassium chloride decreases sodium and fluid reabsorption in the proximal tubule (5), and a high-potassium diet decreases sodium and fluid reabsorption in the loop of Henle (3, 25, 64, 66). These effects in the proximal segments will tend to stimulate distal potassium secretion. A high-potassium diet also has direct effects on the distal tubule to modify potassium transport. Wang et al. (72) showed that a high-potassium diet increased the density of the apical small-conductance potassium channel SK, the native ROMK channel, in rat cortical collecting tubule. Subsequent studies showed that both long-term (12–16 days) (48) or short-term (6 or 48 h) (51) exposure to a high-potassium diet increased SK density in rat cortical collecting tubule. In a recent paper, Frindt and Palmer (17) have updated these findings using an inhibitor of ROMK, tertiapin-Q (TPNQ), which does not inhibit the closely related inwardly rectifying potassium channels Kir4.1 and Kir5.1 found on the basolateral membrane of tubular epithelial cells. This allowed the authors to accurately measure ROMK activity in rat connecting tubule and cortical collecting duct under whole-cell clamp conditions. This overcomes some of the obstacles of estimating the whole-cell density of channels using the cell-attached patch technique, which is subject to sampling errors due to nonrandom distribution of channels. They found that a high-potassium diet increased ROMK current by approximately threefold in both the connecting tubule and cortical collecting duct. Conversely, a low-potassium diet decreased ROMK current by 35% in the cortical collecting duct and by 50% in the connecting tubule. ROMK currents were similar in the connecting tubule and cortical collecting tubules from rats on a high-potassium diet, and a current was also detected in the outer medullary collecting duct under these conditions (17). This study helps resolve conflicting data from previous studies with regard to the effects of changes on dietary potassium in the connecting tubule vs. collecting duct (1, 13, 51, 74).

Using a different approach, in situ biotinylation, the same authors examined cell surface ROMK in rats fed low- or high-potassium diets. While total ROMK expression was decreased with a low-potassium diet and increased with a high-potassium diet, surface expression was altered (increased) only by a high-potassium diet (14). In addition, as expected, ENaC levels were generally increased with a high-potassium diet and decreased with a low-potassium diet. Interestingly, surface levels of NCC were decreased in rats fed a high-potassium diet (14). A decrease in sodium reabsorption via NCC would allow increased sodium reabsorption via ENaC, thus enhancing potassium secretion. This effect of potassium loading is in contrast to that of a low-sodium diet, in which surface levels of both ENaC and NCC were increased (16). Thus two maneuvers which increase serum aldosterone levels, that is, increased dietary potassium or decreased dietary sodium, have similar effects on ENaC but opposite effects on NCC.

A study by Vallon et al. (67) further supports the importance of coordinated regulation of NCC and ROMK for the renal potassium homeostatic response to variations in dietary potassium intake. Vallon et al. showed that a low-sodium diet increased NCC expression, whereas a high-potassium diet decreased it. These investigators also examined phosphorylation of NCC at amino acids known to be important for cotransporter activation (55). Phosphorylation was increased by a low-sodium diet, consistent with cotransporter activation, and decreased by a high-potassium diet, consistent with cotransporter inhibition. Furthermore, the effects of dietary sodium and potassium were dissociated at the level of intracellular signaling. In mice lacking serum- and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase 1 (Sgk1), a known mediator of aldosterone action (68), the upregulation of NCC by a low-sodium diet was attenuated, whereas downregulation of NCC by high potassium diet was intact in the knockout mice (67). Together with the facts that a high-potassium diet increases serum aldosterone levels and aldosterone upregulates rather than downregulates NCC, this result supports that NCC regulation in response to dietary potassium intake is independent of aldosterone. This is reminiscent of ROMK, in which channel density is increased by a high-potassium diet, but not by exogenous aldosterone infusion or aldosterone induction by a low-sodium diet (48, 49, 51).

Role for WNK1 in regulation of NCC, NKCC2, and ROMK.

What is the mechanism of aldosterone-independent up- and downregulation of ROMK and NCC, respectively, in a high-potassium diet? Recent studies suggest that the with-no-lysine kinase WNK1 may be important. WNK1 is mutated in pseudohypoaldosteronism type II, an autosomal dominant disorder in which patients are invariably hyperkalemic (76). In the kidney, two alternative transcripts of WNK1 are expressed, a full-length transcript called long WNK1 (L-WNK1), and a shorter, kidney-specific transcript lacking the kinase domain (KS-WNK1) (8, 45). In Xenopus laevis oocytes and cultured cells, L-WNK1 decreases surface ROMK expression by stimulating clathrin-dependent endocytosis, and KS-WNK1 inhibits this activity of L-WNK1 in a dominant-negative fashion (7, 24, 32, 70). In X. laevis oocytes and cultured cells, L-WNK1 upregulates the surface expression of NCC (55, 65). KS-WNK1 antagonizes the effect of L-WNK1 on NCC (65). These results raise the possibility that changes in dietary potassium may affect the ratio of L-WNK1 over KS-WNK1 to regulate ROMK and NCC. In support of this hypothesis, several groups have shown that the ratio of L-WNK1 to KS-WNK1 is decreased in animals fed a high-potassium diet and increased in animals fed a low-potassium diet (32, 44, 70). Levels of KS-WNK1 appear more sensitive to modulation by dietary potassium than levels of L-WNK1, and a high-potassium diet appears to be a more powerful regulator than a low-potassium diet (32, 44, 70). This is consistent with the greater changes in ROMK density seen with a high-potassium diet than with a low-potassium diet, as found in the analysis by Frindt and Palmer (17).

Three recent papers examine a role for KS-WNK1 in vivo. Liu et al. (35) generated transgenic mice overexpressing KS-WNK1 in renal tubular epithelial cells. As expected from the oocyte and cell culture studies described above, immunofluorescent staining of ROMK was higher in the KS-WNK1-overexpressing mice. Furthermore, the transgenic mice had lower serum potassium concentrations and higher fractional excretion of potassium, consistent with increased renal potassium clearance (35). In a separate study, Liu et al. (37) further showed that transgenic mice overexpressing KS-WNK1 in renal tubular epithelia have decreased NCC and NCC phosphorylation, as well as decreased thick ascending limb NKCC2 and phospho-NKCC2. Based on cell culture and oocyte studies, the decreased NCC and NKCC2 phosphorylation would be predicted to decrease cotransporter activity in both cases (54, 55). Functionally, this manifests as sodium wasting when the mice are placed on a low-sodium diet. The same authors generated KS-WNK1 knockout mice and found that knockout mice have increased NCC, phospho-NCC, NKCC2, and phospho-NKCC2, retaining sodium when on a high-sodium diet (37). Although renal potassium handling was not examined in detail, these mice become hyperkalemic when fed a high-potassium diet (36).

Hadchouel et al. (23) have also generated a KS-WNK1 knockout mouse and found increased expression of NCC and phospho-NCC in these mice. However, Hadchouel et al. reported that serum potassium levels between knockout and wild-type mice were not different. Reasons for the apparent differences between the two KS-WNK1 knockout models are unknown. Extra- and/or intrarenal compensatory responses, such as upregulation of BK (23), may be contributory.

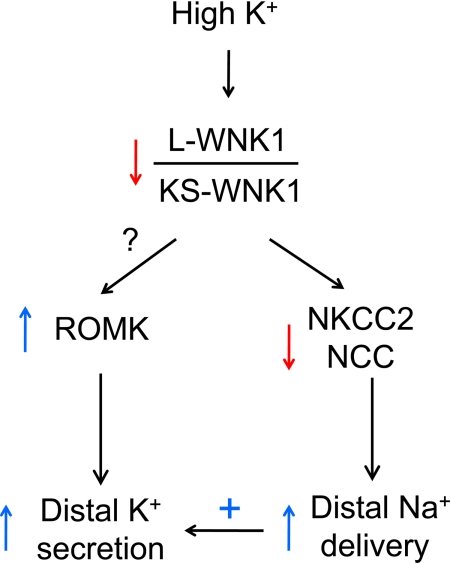

Based on combined information from cell culture and in vivo studies, we propose the following model for future investigation (Fig. 2). A high-potassium diet decreases the ratio of L- over KS-WNK1. A decrease in the ratio of L- to KS-WNK1 decreases sodium reabsorption by the thick ascending limb of the loop of Henle and the distal convoluted tubule, thereby increasing sodium delivery and flow to the connecting and cortical collecting tubules and enhancing potassium secretion by these segments. The decrease in the ratio of L- to KS-WNK1 may also directly increase ROMK levels on the apical membranes of these epithelial cells, allowing increased potassium secretion. A low-potassium diet increases the ratio of L- to KS-WNK1 to regulate ROMK and NCC in the opposite direction. Thus modulation of the ratio of L- to KS-WNK1 may provide integrative control of potassium secretion by affecting the activity of several channels and transporters across multiple segments of the nephron. Future studies will include direct assessment of the effects of changing levels of KS-WNK1 and/or L-WNK1 on ROMK function and renal potassium handling using in vitro microperfusion of isolated tubules and/or patch-clamp recording of native tubules. Other future studies include examination of whether KS-WNK1 regulates NCC and ROMK by antagonizing L-WNK1 in vivo and elucidation of the mechanisms by which dietary potassium regulates levels of KS-WNK1 and L-WNK1. Finally, many studies have shown that WNK4 regulates ROMK and NCC (reviewed in Refs. 57, 73, and 75). The role of WNK4 in the dietary regulation of potassium handling warrants future studies.

Fig. 2.

Integrated regulation of potassium secretion by WNK1. A high-potassium diet decreases the ratio of full-length L-WNK1 to the kidney-specific transcript KS-WNK1, which lacks the kinase domain and inhibits L-WNK1 in a dominant-negative fashion. This occurs by upregulation of KS-WNK1 and downregulation of L-WNK1 by a high potassium diet. As a result, NKCC2 and Na+-Cl− cotransporter (NCC) levels and activity are downregulated. This results in decreased sodium reabsorption in the thick ascending limb of the loop of Henle and the distal convoluted tubule, nephron segments in which electroneutral sodium and chloride reabsorption occurs. Increased sodium is therefore delivered to the downstream aldosterone-sensitive distal nephron, providing additional sodium for electrogenic reabsorption. This allows a more negative transepithelial voltage to develop and increases the driving force for potassium secretion. The decrease in the ratio of L- over KS-WNK1 may increase the level of ROMK, allowing greater potassium secretion across the apical membrane of principal cells in the aldosterone-sensitive distal nephron (connecting tubule, collecting duct). Flow-dependent potassium secretion, for example by BK, is also stimulated by the increased distal flow. The role of WNK1 in BK, Kv1.3 channels and potassium secretion through intercalated cells remains unexplored.

Regulation of ROMK by Intracellular and Extracellular Magnesium

Hypokalemia is a very common electrolyte disorder in clinical medicine and is frequently associated with magnesium deficiency. Hypokalemia associated with magnesium deficiency is refractory to treatment by potassium replacement unless the concomitant magnesium deficiency is corrected. How magnesium deficiency exacerbates hypokalemia is unexplained. ROMK is an inwardly rectifying potassium channel of which outward potassium fluxes through the channel are inhibited by intracellular magnesium (38). The affinity for inhibition of ROMK by intracellular magnesium is modulated by membrane potentials and extracellular potassium concentrations. Based on predicted membrane potentials and extracellular potassium concentrations in the distal nephron, Huang and Kuo (29) proposed that physiological intracellular magnesium concentrations could play a role in regulating potassium secretion by ROMK in the distal nephron. A decrease in intracellular magnesium caused by magnesium deficiency would release the magnesium-mediated inhibition of ROMK and increase potassium secretion, explaining at least partly persistent hypokalemia in magnesium deficiency (29).

A recent study by Yang et al. (79) examined this hypothesis. Using extracellular potassium concentrations simulating luminal potassium levels in the condition of hypokalemia, Yang et al. showed that 0.2–1 mM internal magnesium reduced outward potassium currents in the physiological range of membrane potentials. This regulation occurs in ROMK channels expressed in X. laevis oocytes as well as in native SK channels of rat cortical collecting ducts. Moreover, the authors showed that extracellular magnesium between 0 and 1 mM also reduced outward ROMK currents in a manner that the affinity increased as extracellular potassium decreased. These results indicate that physiological concentrations of intracellular and extracellular magnesium can affect potassium secretion through ROMK and support the hypothesis that magnesium modulation of ROMK plays a role in potassium wasting under conditions of potassium and magnesium depletion. Micropuncture studies examining distal potassium secretion in magnesium-depleted animals will provide direct support for the hypothesis.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grants DK59530 and DK007275. C.-L. Huang holds the Jacob Lemann Professorship in Calcium Transport at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center. C.-J. Cheng is supported by a grant from the Ministry of Defense, Taiwan.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Lawrence Palmer at Weill Medical College of Cornell University for insightful discussions during preparation of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1. Babilonia E, Li D, Wang Z, Sun P, Lin DH, Jin Y, Wang WH. Mitogen-activated protein kinases inhibit the ROMK (Kir 1.1)-like small conductance K channels in the cortical collecting duct. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 2687–2696, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bailey MA, Cantone A, Yan Q, MacGregor GG, Leng Q, Amorim JB, Wang T, Hebert SC, Giebisch G, Malnic G. Maxi-K channels contribute to urinary potassium excretion in the ROMK-deficient mouse model of type II Bartter's syndrome and in adaptation to a high-K diet. Kidney Int 70: 51–59, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Battilana CA, Dobyan DC, Lacy FB, Bhattacharya J, Johnston PA, Jamison RL. Effect of chronic potassium loading on potassium secretion by the pars recta or descending limb of the juxtamedullary nephron in the rat. J Clin Invest 62: 1093–1103, 1978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Beck FX, Dorge A, Blumner E, Giebisch G, Thurau K. Cell rubidium uptake: a method for studying functional heterogeneity in the nephron. Kidney Int 33: 642–651, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brandis M, Keyes J, Windhager EE. Potassium-induced inhibition of proximal tubular fluid reabsorption in rats. Am J Physiol 222: 421–427, 1972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Carrisoza-Gaytan R, Salvador C, Satlin LM, Liu W, Zavilowitz B, Bobadilla NA, Trujillo J, Escobar LI. Potassium secretion by voltage-gated potassium channel Kv1.3 in the rat kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 299: F255–F264, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cope G, Murthy M, Golbang AP, Hamad A, Liu CH, Cuthbert AW, O'Shaughnessy KM. WNK1 affects surface expression of the ROMK potassium channel independent of WNK4. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 1867–1874, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Delaloy C, Lu J, Houot AM, Disse-Nicodeme S, Gasc JM, Corvol P, Jeunemaitre X. Multiple promoters in the WNK1 gene: one controls expression of a kidney-specific kinase-defective isoform. Mol Cell Biol 23: 9208–9221, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dietl P, Stanton BA. Chloride channels in apical and basolateral membranes of CCD cells (RCCT-28A) in culture. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 263: F243–F250, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dutta AK, Khimji AK, Kresge C, Bugde A, Dougherty M, Esser V, Ueno Y, Glaser SS, Alpini G, Rockey DC, Feranchak AP. Identification and functional characterization of TMEM16A, a Ca2+-activated Cl- channel activated by extracellular nucleotides, in biliary epithelium. J Biol Chem 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fernandez R, Bosqueiro JR, Cassola AC, Malnic G. Role of Cl− in electrogenic H+ secretion by cortical distal tubule. J Membr Biol 157: 193–201, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Field MJ, Stanton BA, Giebisch GH. Differential acute effects of aldosterone, dexamethasone, and hyperkalemia on distal tubular potassium secretion in the rat kidney. J Clin Invest 74: 1792–1802, 1984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Frindt G, Palmer LG. Apical potassium channels in the rat connecting tubule. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 287: F1030–F1037, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Frindt G, Palmer LG. Effects of dietary K on cell-surface expression of renal ion channels and transporters. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 299: F890–F897, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Frindt G, Palmer LG. K+ secretion in the rat kidney: Na+ channel-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 297: F389–F396, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Frindt G, Palmer LG. Surface expression of sodium channels and transporters in rat kidney: effects of dietary sodium. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 297: F1249–F1255, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Frindt G, Shah A, Edvinsson J, Palmer LG. Dietary K regulates ROMK channels in connecting tubule and cortical collecting duct of rat kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 296: F347–F354, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Galietta LJ. The TMEM16 protein family: a new class of chloride channels? Biophys J 97: 3047–3053, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ginns SM, Knepper MA, Ecelbarger CA, Terris J, He X, Coleman RA, Wade JB. Immunolocalization of the secretory isoform of Na-K-Cl cotransporter in rat renal intercalated cells. J Am Soc Nephrol 7: 2533–2542, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Good DW, Velazquez H, Wright FS. Luminal influences on potassium secretion: low sodium concentration. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 246: F609–F619, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Good DW, Wright FS. Luminal influences on potassium secretion: sodium concentration and fluid flow rate. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 236: F192–F205, 1979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Grimm PR, Irsik DL, Settles DC, Holtzclaw JD, Sansom SC. Hypertension of Kcnmb1-/- is linked to deficient K secretion and aldosteronism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 11800–11805, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hadchouel J, Soukaseum C, Busst C, Zhou XO, Baudrie V, Zurrer T, Cambillau M, Elghozi JL, Lifton RP, Loffing J, Jeunemaitre X. Decreased ENaC expression compensates the increased NCC activity following inactivation of the kidney-specific isoform of WNK1 and prevents hypertension. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 18109–18114, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. He G, Wang HR, Huang SK, Huang CL. Intersectin links WNK kinases to endocytosis of ROMK1. J Clin Invest 117: 1078–1087, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Higashihara E, Kokko JP. Effects of aldosterone on potassium recycling in the kidney of adrenalectomized rats. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 248: F219–F227, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hirsch D, Kashgarian M, Boulpaep EL, Hayslett JP. Role of aldosterone in the mechanism of potassium adaptation in the initial collecting tubule. Kidney Int 26: 798–807, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Holtzclaw JD, Grimm PR, Sansom SC. Intercalated cell BK-alpha/beta4 channels modulate sodium and potassium handling during potassium adaptation. J Am Soc Nephrol 21: 634–645, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Holtzclaw JD, Liu L, Grimm PR, Sansom SC. Shear stress-induced volume decrease in C11-MDCK cells by BK-α/β4. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 299: F507–F516, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Huang CL, Kuo E. Mechanism of hypokalemia in magnesium deficiency. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 2649–2652, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Huang F, Rock JR, Harfe BD, Cheng T, Huang X, Jan YN, Jan LY. Studies on expression and function of the TMEM16A calcium-activated chloride channel. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 21413–21418, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Khuri RN, Strieder WN, Giebisch G. Effects of flow rate and potassium intake on distal tubular potassium transfer. Am J Physiol 228: 1249–1261, 1975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lazrak A, Liu Z, Huang CL. Antagonistic regulation of ROMK by long and kidney-specific WNK1 isoforms. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 1615–1620, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Light DB, Schwiebert EM, Fejes-Toth G, Naray-Fejes-Toth A, Karlson KH, McCann FV, Stanton BA. Chloride channels in the apical membrane of cortical collecting duct cells. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 258: F273–F280, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Liu W, Schreck C, Zavilowitz B, Kleyman TR, Satlin LM. Regulation of BK channel-mediated net K secretion (JK) by NKCC in the cortical collecting duct (CCD) (Abstract). J Am Soc Nephrol 21: 66A, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 35. Liu Z, Wang HR, Huang CL. Regulation of ROMK channel and K+ homeostasis by kidney-specific WNK1 kinase. J Biol Chem 284: 12198–12206, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Liu Z, Xie J, Wu T, Huang CL. Role of kidney-specific WNK1 in the regulation of Na and K transport in mice (Abstract). J Am Soc Nephrol 20: 66A, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 37. Liu Z, Xie J, Wu T, Truong T, Auchus RJ, Huang CL. Downregulation of NCC and NKCC2 cotransporters by kidney-specific WNK1 revealed by gene disruption and transgenic mouse models. Hum Mol Genet 20: 855–866, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lu Z, MacKinnon R. Electrostatic tuning of Mg2+ affinity in an inward-rectifier K+ channel. Nature 371: 243–246, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Malnic G, Berliner RW, Giebisch G. Flow dependence of K+ secretion in cortical distal tubules of the rat. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 256: F932–F941, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Malnic G, Klose RM, Giebisch G. Micropuncture study of renal potassium excretion in the rat. Am J Physiol 206: 674–686, 1964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Meneton P, Loffing J, Warnock DG. Sodium and potassium handling by the aldosterone-sensitive distal nephron: the pivotal role of the distal and connecting tubule. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 287: F593–F601, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Muto S, Tsuruoka S, Miyata Y, Fujimura A, Kusano E, Wang W, Seldin D, Giebisch G. Basolateral Na+/H+ exchange maintains potassium secretion during diminished sodium transport in the rabbit cortical collecting duct. Kidney Int 75: 25–30, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Najjar F, Zhou H, Morimoto T, Bruns JB, Li HS, Liu W, Kleyman TR, Satlin LM. Dietary K+ regulates apical membrane expression of maxi-K channels in rabbit cortical collecting duct. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 289: F922–F932, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. O'Reilly M, Marshall E, Macgillivray T, Mittal M, Xue W, Kenyon CJ, Brown RW. Dietary electrolyte-driven responses in the renal WNK kinase pathway in vivo. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 2402–2413, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. O'Reilly M, Marshall E, Speirs HJ, Brown RW. WNK1, a gene within a novel blood pressure control pathway, tissue-specifically generates radically different isoforms with and without a kinase domain. J Am Soc Nephrol 14: 2447–2456, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ousingsawat J, Martins JR, Schreiber R, Rock JR, Harfe BD, Kunzelmann K. Loss of TMEM16A causes a defect in epithelial Ca2+-dependent chloride transport. J Biol Chem 284: 28698–28703, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Pacha J, Frindt G, Sackin H, Palmer LG. Apical maxi K channels in intercalated cells of CCT. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 261: F696–F705, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Palmer LG, Antonian L, Frindt G. Regulation of apical K and Na channels and Na/K pumps in rat cortical collecting tubule by dietary K. J Gen Physiol 104: 693–710, 1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Palmer LG, Frindt G. Aldosterone and potassium secretion by the cortical collecting duct. Kidney Int 57: 1324–1328, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Palmer LG, Frindt G. High-conductance K channels in intercalated cells of the rat distal nephron. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 292: F966–F973, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Palmer LG, Frindt G. Regulation of apical K channels in rat cortical collecting tubule during changes in dietary K intake. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 277: F805–F812, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Pluznick JL, Wei P, Carmines PK, Sansom SC. Renal fluid and electrolyte handling in BKCa-β1−/− mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 284: F1274–F1279, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Pluznick JL, Wei P, Grimm PR, Sansom SC. BK-β1 subunit: immunolocalization in the mammalian connecting tubule and its role in the kaliuretic response to volume expansion. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 288: F846–F854, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Ponce-Coria J, San-Cristobal P, Kahle KT, Vazquez N, Pacheco-Alvarez D, de Los Heros P, Juarez P, Munoz E, Michel G, Bobadilla NA, Gimenez I, Lifton RP, Hebert SC, Gamba G. Regulation of NKCC2 by a chloride-sensing mechanism involving the WNK3 and SPAK kinases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 8458–8463, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Richardson C, Rafiqi FH, Karlsson HK, Moleleki N, Vandewalle A, Campbell DG, Morrice NA, Alessi DR. Activation of the thiazide-sensitive Na+-Cl− cotransporter by the WNK-regulated kinases SPAK and OSR1. J Cell Sci 121: 675–684, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Rieg T, Vallon V, Sausbier M, Sausbier U, Kaissling B, Ruth P, Osswald H. The role of the BK channel in potassium homeostasis and flow-induced renal potassium excretion. Kidney Int 72: 566–573, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Rodan AR, Huang CL. Distal potassium handling based on flow modulation of maxi-K channel activity. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 18: 350–355, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Sampaio MS, Bezerra IP, Pecanha FL, Fonseca PH, Capella MA, Lopes AG. Lack of Na+,K+-ATPase expression in intercalated cells may be compensated by Na+-ATPase: a study on MDCK-C11 cells. Cell Mol Life Sci 65: 3093–3099, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Sauer M, Dorge A, Thurau K, Beck FX. Effect of ouabain on electrolyte concentrations in principal and intercalated cells of the isolated perfused cortical collecting duct. Pflügers Arch 413: 651–655, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Schreiber R, Uliyakina I, Kongsuphol P, Warth R, Mirza M, Martins JR, Kunzelmann K. Expression and function of epithelial anoctamins. J Biol Chem 285: 7838–7845, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Schwiebert EM, Karlson KH, Friedman PA, Dietl P, Spielman WS, Stanton BA. Adenosine regulates a chloride channel via protein kinase C and a G protein in a rabbit cortical collecting duct cell line. J Clin Invest 89: 834–841, 1992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Sorensen MV, Matos JE, Praetorius HA, Leipziger J. Colonic potassium handling. Pflügers Arch 459: 645–656, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Stanton B, Pan L, Deetjen H, Guckian V, Giebisch G. Independent effects of aldosterone and potassium on induction of potassium adaptation in rat kidney. J Clin Invest 79: 198–206, 1987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Stokes JB. Consequences of potassium recycling in the renal medulla. Effects of ion transport by the medullary thick ascending limb of Henle's loop. J Clin Invest 70: 219–229, 1982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Subramanya AR, Yang CL, Zhu X, Ellison DH. Dominant-negative regulation of WNK1 by its kidney-specific kinase-defective isoform. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 290: F619–F624, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Unwin R, Capasso G, Giebisch G. Potassium and sodium transport along the loop of Henle: effects of altered dietary potassium intake. Kidney Int 46: 1092–1099, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Vallon V, Schroth J, Lang F, Kuhl D, Uchida S. Expression and phosphorylation of the Na+-Cl- cotransporter NCC in vivo is regulated by dietary salt, potassium, and SGK1. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 297: F704–F712, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Vallon V, Wulff P, Huang DY, Loffing J, Volkl H, Kuhl D, Lang F. Role of Sgk1 in salt and potassium homeostasis. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 288: R4–R10, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Velazquez H, Ellison DH, Wright FS. Chloride-dependent potassium secretion in early and late renal distal tubules. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 253: F555–F562, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Wade JB, Fang L, Liu J, Li D, Yang CL, Subramanya AR, Maouyo D, Mason A, Ellison DH, Welling PA. WNK1 kinase isoform switch regulates renal potassium excretion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 8558–8563, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Wall SM, Knepper MA, Hassell KA, Fischer MP, Shodeinde A, Shin W, Pham TD, Meyer JW, Lorenz JN, Beierwaltes WH, Dietz JR, Shull GE, Kim YH. Hypotension in NKCC1 null mice: role of the kidneys. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 290: F409–F416, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Wang WH, Schwab A, Giebisch G. Regulation of small-conductance K+ channel in apical membrane of rat cortical collecting tubule. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 259: F494–F502, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Wang WH, Yue P, Sun P, Lin DH. Regulation and function of potassium channels in aldosterone-sensitive distal nephron. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 19: 463–470, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Wei Y, Bloom P, Gu R, Wang W. Protein-tyrosine phosphatase reduces the number of apical small conductance K+ channels in the rat cortical collecting duct. J Biol Chem 275: 20502–20507, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Welling PA, Ho K. A comprehensive guide to the ROMK potassium channel: form and function in health and disease. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 297: F849–F863, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Wilson FH, Disse-Nicodeme S, Choate KA, Ishikawa K, Nelson-Williams C, Desitter I, Gunel M, Milford DV, Lipkin GW, Achard JM, Feely MP, Dussol B, Berland Y, Unwin RJ, Mayan H, Simon DB, Farfel Z, Jeunemaitre X, Lifton RP. Human hypertension caused by mutations in WNK kinases. Science 293: 1107–1112, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Wingo CS. Reversible chloride-dependent potassium flux across the rabbit cortical collecting tubule. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 256: F697–F704, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Wingo CS, Seldin DW, Kokko JP, Jacobson HR. Dietary modulation of active potassium secretion in the cortical collecting tubule of adrenalectomized rabbits. J Clin Invest 70: 579–586, 1982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Yang L, Frindt G, Palmer LG. Magnesium modulates ROMK channel-mediated potassium secretion. J Am Soc Nephrol 21: 2109–2116, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Youn JH, McDonough AA. Recent advances in understanding integrative control of potassium homeostasis. Annu Rev Physiol 71: 381–401, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Young DB. Quantitative analysis of aldosterone's role in potassium regulation. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 255: F811–F822, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]