Abstract

A synthetic approach to the C17-benzene ansamycins via metal catalyzed C-C coupling is described. Key bond formations include direct iridium catalyzed carbonyl crotylation from the alcohol oxidation level followed by chelation-controlled Sakurai-Seyferth dienylation to form the stereotriad, which is attached to the arene via Suzuki cross-coupling. The diene-containing carboxylic acid is prepared using rhodium catalyzed acetylene-aldehyde reductive C-C coupling mediated by gaseous hydrogen. Finally, RCM delivers the cytotrienin core.

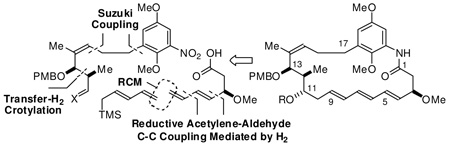

Beginning with the discovery of the antibacterial rifamycin B, ansamycin antibiotics continue to evoke interest as antibiotic and antineoplastic agents.1 An important ansamycin subclass is represented by the ansatrienins, which are classified as triene-containing C17-benzene ansamycins. Members of this subclass, which are produced from various Steptomyces and Bacillus species, include the mycotrienins and mycotrienols,2 the trienomycins3 and the cytotrienins (Figure 1).4 Whereas the mycotrienins exhibit potent anti-fungal activity,2d,e the trienomycins and cytotrienins display antineoplastic properties.3a,5 For example, cytotrienin A induces apoptosis in human acute promyelocytic leukemia HL-60 cells (ED50 = 7.7 nM).5c Following their stereochemical assignment,6 total syntheses of trienomycins A and F and thiazinotrienomycin E were reported by Smith, 7a–c total syntheses of mycotrienol I and mycotrienin I were reported by Panek7d,e and a total synthesis of cytotrienin A was reported by Hayashi.7f Finally, Kirschning and Panek reported syntheses of the ansatrienol and cytotrienin cores, respectively.8 Here, we report initial efforts toward the development of a synthetic approach to triene-containing C17-benzene ansamycins featuring C-C bond forming hydrogenations and transfer hydrogenations developed in our laboratory.9

Figure 1.

Representative ansatrienins: C17-benzene triene-ansamycin antibiotics.

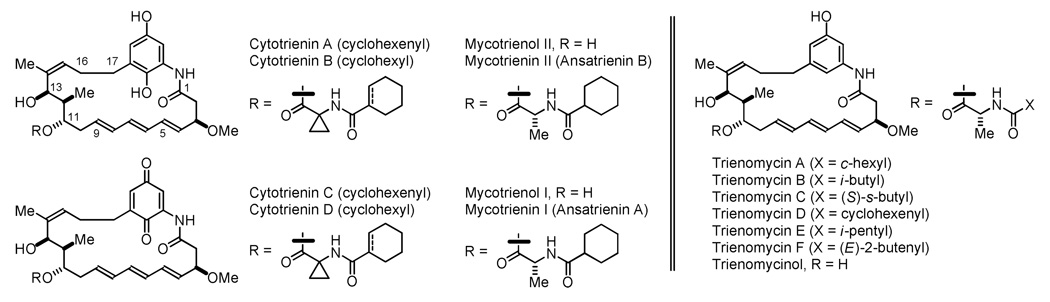

Retrosynthetically, it was envisioned that diverse C17-benzene ansamycins may be accessed through modular assembly of fragments A–D. Specifically, Suzuki cross-coupling of vinyl bromide A and the organoboron building block B would deliver an arene-containing C11–C17 substructure. Chelation-controlled pentadienylation of the latent C11-aldehyde employing reagent C followed by reduction of the nitroarene and amidation of the resulting aniline with carboxylic acid D provides a bis(diene), which upon macrocyclization via ruthenium catalyzed ring closing metathesis, as established by Panek,8b would deliver the C17-benzene triene-ansamycin core (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

Retrosynthetic analysis of C17-benzene trieneansamycins via metal catalyzed C-C coupling.

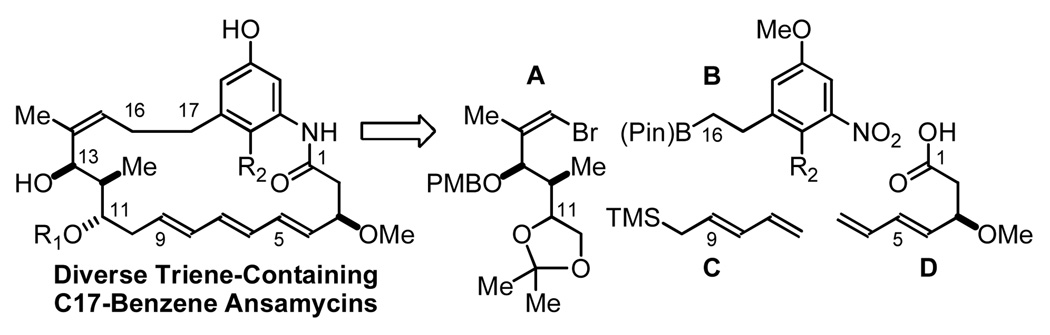

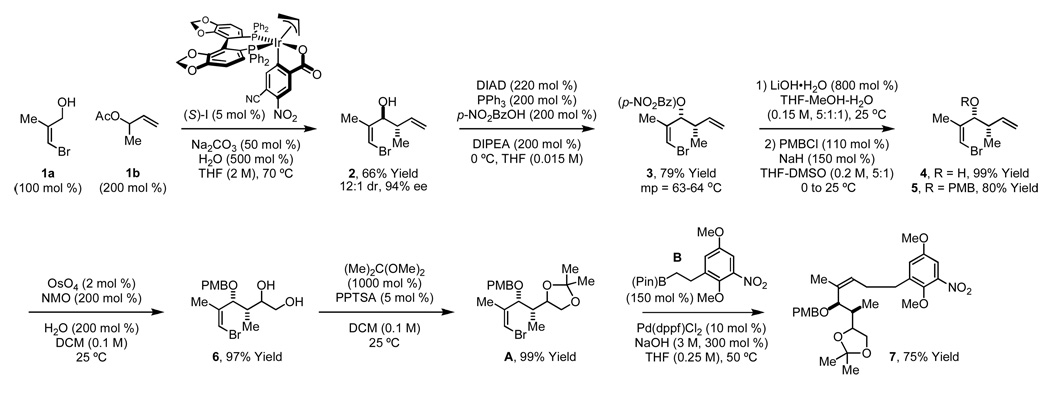

Synthesis of fragment A, which embodies the characteristic C17-benzene ansamycin stereotriad, begins with direct carbonyl crotylation of allylic alcohol 1a10 mediated by α-methyl allyl acetate 1b under the conditions of iridium catalyzed transfer hydrogenation.11 High levels of anti-diastereo- and enantioselectivity are obtained using the isolated ortho-cyclometallated iridium C,O-benzoate precatalyst modified by (S)-SEGPHOS. As efforts toward corresponding syn-diastereoselective processes are underway,11d the present first-generation synthesis requires conversion of the anti-adduct to the syn-diastereomer via Mitsunobu inversion employing p-nitrobenzoic acid12 to deliver the crystalline p-nitrobenzoate 3. Saponification of 3 followed by Williamson ether synthesis provides the p-methoxybenzyl ether 5. Catalytic dihydroxylation to furnish 6 followed by conversion to the acetonide completes the synthesis of fragment A (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of the stereotriad-containing fragment A and Suzuki cross-coupling with fragment B.a

aSee Supporting Information for detailed experimental procedures.

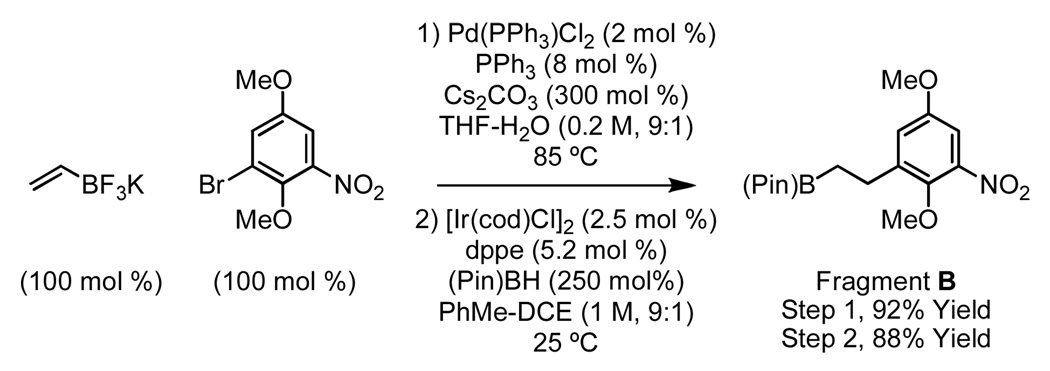

The synthesis of fragment B begins with the Suzuki-Molander coupling of 1-bromo-2,5-dimethoxy-3-nitrobenzene with potassium ethenyltrifluoroborate.13 Hydroboration of the resulting vinylarene under standard conditions employing 9-BBN occurred regioselectively, but subsequent Suzuki coupling to produce 7 was problematic. For this reason, Miyaura’s method for iridium catalyzed hydroboration employing pinacol borane was used, which delivered fragment B in a regioselective fashion (Scheme 3).14

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of fragment B.a

aSee Supporting Information for detailed experimental procedures.

The Suzuki coupling of fragments A and B was especially challenging. However, after screening numerous palladium sources and phosphine ligands, a remarkably simple protocol was identified, in which fragments A and B were exposed to Pd(dppf)Cl2 in the presence of sodium hydroxide to furnish the product of C-C coupling 7 in 75% isolated yield (Scheme 2).

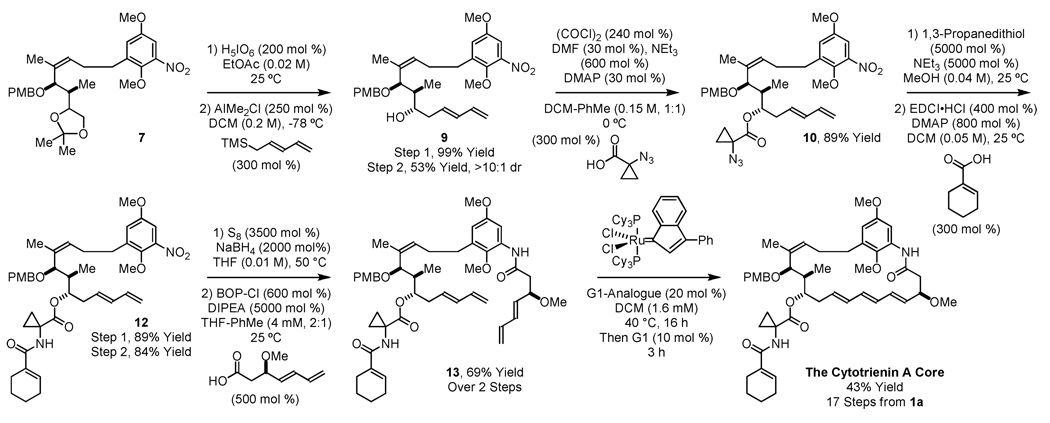

At this point, elaboration of 7 to the cytotrienin core was set as an initial goal of our first-generation synthetic approach to the C17-benzene triene-ansamycins. Toward this end, exposure of 7 to periodic acid in ethyl acetate solvent directly provides aldehyde 8,15 which was subjected immediately to conditions for chelation-controlled16 pentadienylation.17 Gratifyingly, the desired adduct 9 was formed in a stereoselective fashion. To install the cytotrienin side-chain, Hayashi’s protocol was employed.7f Specifically, alcohol 9 was converted to the α-azido-cyclopropane carboxylic ester 10. Reduction of the azide followed by acylation of the resulting amine 11 using cyclohexene carboxylic acid delivers 12 (Scheme 4).

Scheme 4.

Elaboration of Suzuki cross-coupling product 7 to the cytotrienin core.a

aSee Supporting Information for detailed experimental procedures.

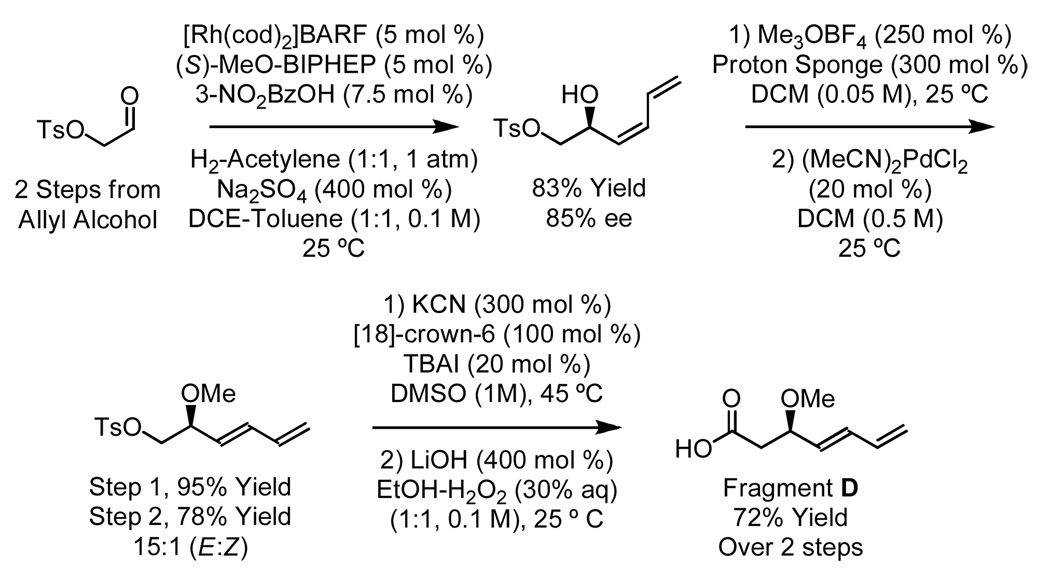

Elaboration of 12 to the cytotrienin A core requires preparation of diene-containing carboxylic acid D. Previously, carboxylic acid D was produced in 12 steps in 16% overall yield.7f Hydrogen-mediated C-C coupling of acetylene18 to the p-toluenesulfonate of hydroxy acetaldehyde delivers the indicated product of (Z)-butadienylation, which upon O-methylation and isomerization of the diene19 provide the indicated (E)-homoallylic sulfonate. Displacement of the p-toluenesulfonate by cyanide and, finally, hydrolysis of the resulting nitrile delivers carboxylic acid D in 7 steps from allyl alcohol in 32% overall yield (Scheme 5). With carboxylic acid D in hand, compound 12 is transformed to bis(diene) 13 via reduction of the nitroarene employing NaBH2S320 followed by acylation of the resulting aniline (Scheme 4).

Scheme 5.

Synthesis of diene-containing carboxylic acid D via hydrogen-mediated C-C coupling.a

aSee Supporting Information for detailed experimental procedures.

Initial exploration of the ruthenium catalyzed RCM reaction of bis(diene) 13 and related model systems revealed exceptional sensitivity to both the catalyst and the substituent at C11. For example, in model studies involving the corresponding C11 TBS-ether of bis(diene) 13, RCM using the Grubbs-Hoveyda-II catalyst occurred to deliver the diene product exclusively. Eventually, it was found that diene formation is suppressed for O-acyl derivatives at C11 and, gratifyingly, the actual cytotrienin A side chain proved ideal. Thus, using the indenylidene analogue of the first generation Grubb’s metathesis catalyst,21 bis(diene) 13 is converted to the cytotrienin A core in 43% yield. Difficulties encountered in the removal of the methyl ether functionality prevented conversion of this material to the natural product.

In summary, we report a first-generation approach to the C17-benzene triene-ansamycins, as demonstrated by the synthesis of the cytotrienin A core in 17 steps from alcohol 1a (longest linear sequence). This study serves as prelude to second-generation routes of greater step-economy, which will incorporate syn-diastereo- and enantioselective carbonyl crotylation of alcohol 1a and the use of phenolic protecting groups amenable to late-stage cleavage.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment is made to the Robert A. Welch Foundation (F-0038), the NIH-NIGMS (RO1-GM069445) and the University of Texas at Austin, Center for Green Chemistry and Catalysis for partial support of this research. The Humboldt Foundation is acknowledged for postdoctoral fellowship support (MR).

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available. Characterization data for all new compounds (1H NMR, 13C NMR, IR, HRMS, [α]). This material is available free of charge via the internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.For selected reviews on ansamycin natural products, see: Wrona IE, Agouridas V, Panek JS. C. R. Acad. Sci., Paris. 2008;11:1483. Funayama S, Cordell GA. In: Studies in Natural Products Chemistry. Atta-ur-Rahman, editor. Vol. 23. New York: Elsevier; 2000. pp. 51–106.

- 2.For isolation of mycotrienols I and II and mycotrienins I and II (ansatrienins A and B), see: Weber W, Zuehner H, Damberg M, Russ P, Zeeck A. Zbl. Bakt. Hyg., Abt. Orig. C2. 1981:122. Zeeck A, Damberg M, Russ P. Tetrahedron Lett. 1982;23:59. Sugita M, Furihata K, Seto H, Otake N, Sasaki T. Agric. Biol. Chem. 1982;46:1111. Sugita M, Natori Y, Sasaki T, Furihata K, Shimazu A, Seto H, Otake N. J. Antibiot. 1982;35:1460. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.35.1460. Sugita M, Sasaki T, Furihata K, Seto H, Otake N. J. Antibiot. 1982;35:1467. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.35.1467. Sugita M, Natori Y, Sueda N, Furihata K, Seto H, Otake N. J. Antibiot. 1982;35:1474. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.35.1474. Sugita M, Hiramoto S, Ando C, Sasaki T, Furihata K, Seto H, Otake N. J. Antibiot. 1985;38:799. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.38.799.

- 3.For isolation of trienomycins A-F, see: Umezawa I, Funayama S, Okada K, Iwasaki K, Satoh J, Masuda K, Komiyama K. J. Antibiot. 1985;38:699. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.38.699. Hiramoto S, Sugita M, Ando C, Sasaki T, Furihata K, Seto H, Otake N. J. Antibiot. 1985;38:1103. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.38.1103. Funayama S, Okada K, Komiyama K, Umezawa I. J. Antibiot. 1985;38:1107. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.38.1107. Funayama S, Okada K, Iwasaki K, Komiyama K, Umezawa I. J. Antibiot. 1985;38:1677. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.38.1677. Nomoto H, Katsumata S, Takahashi K, Funayama S, Komiyama K, Umezawa I, Omura S. J. Antibiot. 1989;42:1677. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.42.479. Smith AB, III, Wood JL, Gould AE, Omura S, Komiyama K. Tetrahedron Lett. 1991;32:1627.

- 4.For isolation of cytotrienin A–D, see: Zhang H-P, Kakeya H, Osada H. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997;38:1789. Kakeya H, Zhang H-P, Kobinata K, Onose R, Onozawa C, Kudo T, Osada H. J. Antibiot. 1997;50:370. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.50.370. Osada H, Kakeya H, Zhang H-P, Kobinata K. PCT Int. Appl. 1998 WO 9823594.

- 5.(a) Komiyama K, Hirokawa Y, Yamaguchi H, Funayama S, Masuda K, Anraku Y, Umezawa I, Omura S. J. Antibiot. 1987;40:1768. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.40.1768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Funayama S, Anraku Y, Mita A, Yang ZB, Shibata K, Komiyama K, Umezawa I, Omura S. J. Antibiot. 1988;41:1223. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.41.1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Kakeya H, Zhang H-p, Kobinata K, Onose R, Onozawa C, Kudo T, Osada H. J. Antibiot. 1997;50:370. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.50.370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.For stereochemical assignment of the trienomycins and mycotrienins, see: Smith AB, III, Wood JL, Wong W, Gould AE, Rizzo CJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990;112:7425. Smith AB, III, Wood JL, Omura S. Tetrahedron Lett. 1991;32:841. Smith AB, III, Barbosa J, Hosokawa N, Naganawa H, Takeuchi T. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998;39:2891. Smith AB, III, Wood JL, Wong W, Gould AE, Rizzo CJ, Barbosa J, Funayama S, Komiyama K, Omura S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996;118:8308.

- 7.For the total and formal syntheses of triene-ansamycins, see: (a) Trienomycins A and F and thiazinotrienomycin E: Smith AB, III, Barbosa J, Wong W, Wood JL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;117:10777. Smith AB, III, Barbosa J, Wong W, Wood JL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996;118:8316. Smith AB, III, Wan Z. J. Org. Chem. 2000;65:3738. doi: 10.1021/jo991958j. (d) Mycotrienol I and mycotrienin I: Panek JS, Masse CE. J. Org. Chem. 1997;62:8290. doi: 10.1021/jo971793j. Masse CE, Yang M, Solomon J, Panek JS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:4123. (f)Cytotrienin A: Hayashi Y, Shoji M, Ishikawa H, Yamaguchi J, Tamaru T, Imai H, Nishigaya Y, Takabe K, Kakeya H, Osada H. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:6657. doi: 10.1002/anie.200802079.

- 8.For syntheses of the ansatrienol and cytotrienin cores, see: Kashin D, Meyer A, Wittenberg R, Schoning K-U, Kamlage S, Kirschning A. Synthesis. 2007:304. Evano G, Schaus JV, Panek JS. Org. Lett. 2004;6:525. doi: 10.1021/ol036284k.

- 9.For selected reviews on C-C bond forming hydrogenation and transfer hydrogenation, see: Ngai M-Y, Kong JR, Krische MJ. J. Org. Chem. 2007;72:1063. doi: 10.1021/jo061895m. Skucas E, Ngai M-Y, Komanduri V, Krische MJ. Acc. Chem. Res. 2007;40:1394. doi: 10.1021/ar7001123. Patman RL, Bower JF, Kim IS, Krische MJ. Aldrichim. Acta. 2008;41:95. Shibahara F, Krische MJ. Chem. Lett. 2008;37:1102. doi: 10.1246/cl.2008.1102. Bower JF, Kim IS, Patman RL, Krische MJ. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009;48:34. doi: 10.1002/anie.200802938. Han SB, Kim IS, Krische MJ. Chem. Commun. 2009:7278. doi: 10.1039/b917243m. Bower JF, Krische MJ. Top. Organomet. Chem. 2011;43:107. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-15334-1_5.

- 10.Alcohol 1a was prepared using a variation of the literature procedure: Fang G-H, Yan J-Z, Yang J, Deng M-Z. Synthesis. 2006:1148. Experimental details are included in the Supporting Information.

- 11.For enantioselective iridium catalyzed carbonyl crotylation from the alcohol oxidation level, see: Kim IS, Han SB, Krische MJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:2514. doi: 10.1021/ja808857w. Itoh J, Han SB, Krische MJ. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009;48:6313. doi: 10.1002/anie.200902328. Bechem B, Patman RL, Hashmi ASK, Krische MJ. J. Org. Chem. 2010;75:1795. doi: 10.1021/jo902697g. Zbieg JR, Fukuzumi T. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2010;352:2416. doi: 10.1002/adsc.201000599. Han SB, Hassan A, Kim I-S, Krische MJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:15559. doi: 10.1021/ja1082798.

- 12.Martin SF, Dodge JA. Tetrahedron Lett. 1991;32:3017. [Google Scholar]

- 13.For recent reviews, see: Molander GA, Figueroa R. Aldrichim. Acta. 2005;38:49. Molander GA, Sandrock DL. Curr. Opin. Drug Disc. Dev. 2009;12:811.

- 14.Yamamoto Y, Fujikawa R, Umemoto T, Miyaura N. Tetrahedron. 2004;60:10695. [Google Scholar]

- 15.(a) Wu W-L, Wu Y-L. J. Org. Chem. 1993;58:3586. [Google Scholar]; (b) Xie M, Berges DA, Robins MJ. J. Org. Chem. 1996;61:5178. [Google Scholar]; (c) Curti C, Zanardi F, Battistini L, Sartori A, Rassu G, Azzas L, Roggio A, Pinna L, Casiraghi G. J. Org. Chem. 2006;71:225. doi: 10.1021/jo0520137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Evans DA, Allison BD, Yang MG, Masse, Craig E. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:10840. doi: 10.1021/ja011337j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seyferth D, Pornet J, Weinstein RM. Organometallics. 1982;1:1651. [Google Scholar]

- 18.(a) Kong J-R, Krische MJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:16040. doi: 10.1021/ja0664786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Skucas E, Kong J-R, Krische MJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:7242. doi: 10.1021/ja0715896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Han SB, Kong J-R, Krische MJ. Org. Lett. 2008;10:4133. doi: 10.1021/ol8018874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Williams VM, Kong J-R, Ko B-J, Mantri Y, Brodbelt JS, Baik M-H, Krische MJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:16054. doi: 10.1021/ja906225n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu J, Gaunt MJ, Spencer JB. J. Org. Chem. 2002;67:4627. doi: 10.1021/jo015880u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lalancette JM, Freche A, Brindel JR, Laliberte M. Synthesis. 1972:526. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fürstner A, Grabowski J, Lehmann CW. J. Org. Chem. 1999;64:8275. doi: 10.1021/jo991021i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.