Abstract

Alveolar epithelial type I cell (ATI) wounding is prevalent in ventilator-injured lungs and likely contributes to pathogenesis of “barotrauma” and “biotrauma.” In experimental models most wounded alveolar cells repair plasma membrane (PM) defects and survive insults. Considering the force balance between edge energy at the PM wound margins and adhesive interactions of the lipid bilayer with the underlying cytoskeleton (CSK), we tested the hypothesis that subcortical actin depolymerization is a key facilitator of PM repair. Using real-time fluorescence imaging of primary rat ATI transfected with a live cell actin-green fluorescent protein construct (Lifeact-GFP) and loaded with N-rhodamine phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), we examined the spatial and temporal coordination between cytoskeletal remodeling and PM repair following micropuncture. Membrane integrity was inferred from the fluorescence intensity profiles of the cytosolic label calcein AM. Wounding led to rapid depolymerization of the actin CSK near the wound site, concurrent with accumulation of endomembrane-derived N-rhodamine PE. Both responses were sustained until PM integrity was reestablished, which typically occurs between ∼10 and 40 s after micropuncture. Only thereafter did the actin CSK near the wound begin to repolymerize, while the rate of endomembrane lipid accumulation decreased. Between 60 and 90 s after successful PM repair, after translocation of the actin nucleation factor cortactin, a dense actin fiber network formed. In cells that did not survive micropuncture injury, actin remodeling did not occur. These novel results highlight the importance of actin remodeling in ATI cell repair and suggest molecular targets for modulating the repair process.

Keywords: cortactin, cell injury, Lifeact, plasma membrane

cell wounding and repair are everyday events in tissues such as the epidermis, muscle, gut, and vasculature that are routinely exposed to mechanical stress (21–24). Although cell wounding is rarely evident in the normal lung, it is invariably seen in the alveoli of patients with acute lung injury (ALI) (3, 4). Moreover, the strain imposed on alveolar cells by mechanical ventilation and by the interfacial tension in fluid and foam-filled airways amplifies cellular damage, manifesting as ventilator-induced lung injury (VILI) (8, 49). Although in a rat VILI model a large percentage of wounded resident alveolar cells successfully reseal plasma membrane (PM) defects (16), such cells are undoubtedly an abundant source of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines (18). Accordingly, the extent of alveolar cell repair (and recovery) vs. cell death can modulate the extent and course of VILI. The mechanisms underlying these processes are still under investigation.

Cellular PM lesions repair by several different mechanisms (20). In small wounds, the surface tension at the wound edge is sufficient to promote wound closure by lateral PM lipid flow over an otherwise intact subcortical cytoskeleton (CSK). Repair of larger lesions requires active, calcium-dependent exocytosis of intracellular membranes to the injury site (7, 27, 40). Very large disruptions, such as were generated in sea urchin ova models, trigger the fusion of intracellular organelles to form a membrane patch, which is subsequently directed to the wound site, where it docks and fuses with the PM (20, 25, 40, 42). Lysosomes are a common but certainly not the only intracellular membrane source participating in cell repair (1, 10, 20, 34). Moreover, recent evidence suggests that exocytic PM wound repair mechanisms are intimately linked to and coordinated with endocytic membrane retrieval responses (6, 19, 41).

Our research is motivated by the belief that cell wounding and repair are important drivers of the innate immune response of the injured lung (39, 47). Our specific cell of interest is the primary alveolar epithelial cell type I (ATI), which covers over 90% of the alveolar surface area and is a prominent injury target in ALI and VILI (51). Little is known about whether and how ATI repair, since this cell type has been traditionally difficult to harvest and maintain with sufficient purity in culture. These challenges have recently been overcome (11, 17, 50). We have developed a working model about the sequence of events that influence repair in ATI. It is well known that a PM disruption results in calcium influx followed by exocytosis of calcium-sensitive endosomes to the injury site (40). We hypothesize that this occurs concurrently with the depolymerization of the subcortical actin cytoskeleton. This depolymerization response would serve two purposes: first, to remove a barrier to vesicular trafficking to the PM wound (28), and second, to decrease the adhesive interactions between the inner leaflet of the PM lipid bilayer and the underlying actin cytoskeleton. Repolymerization and remodeling of the actin cytoskeleton would occur only after restoration of PM integrity, since a highly polymerized, tightly woven cytoskeleton would restrict endomembrane trafficking to the wound and would also decrease membrane fluidity and lateral bilayer flow. Using novel experimental tools to examine the coordinated interplay between membrane trafficking and cytoskeletal remodeling in ATI in real time, we tested our proposed model. We have taken advantage of a new green fluorescent protein (GFP)-actin tag, namely Lifeact, which preferentially labels F-actin without altering its kinetics (35). Consistent with our hypothesis we show that wounding by micropuncture causes a rapid depolymerization of the actin CSK near the wound site, coincidental with the accumulation of endomembrane-derived lipids. Both responses are sustained until PM integrity is reestablished, which typically occurs between ∼10–40 s later. Only thereafter does the actin CSK near the wound repolymerize, while the rate of endomembrane lipid accumulation begins to decrease. Translocation of the actin binding protein cortactin to the injury site precedes the subsequent formation of a dense actin fiber network, which peaks between 60 and 90 s after successful PM repair. The implications of these findings relative to the biophysical determinants of wound repair and putative mechanisms cell-protective interventions will be discussed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents

Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium, fetal bovine serum, and penicillin/ampicillin were purchased from Cellgro by Mediatech (Manassas, VA). FuGENE reagents were purchased from Roche Applied Science (Indianapolis, IN). Xfect reagents were purchased from Clontech Laboratories (Mountain View, CA). Jasplakinolide, calcein AM, and Alexa Fluor 488 anti-mouse secondary antibody were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). The monoclonal mouse cortactin antibody was purchased from Millipore (Billerica, MA). Vectashield was purchased from Vector Laboratories (Burlingame, CA). l-α-Phosphatidylethanolamine-N-(lissamine rhodamine B sulfonyl) was purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL).

Cell Culture

The protocol for ATI isolation is described in detail elsewhere (50). To summarize, lungs from Wistar rats were harvested and perfused with a solution containing 140 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 2.5 mM Na2HPO4, 10 mM HEPES, 1.3 mM MgSO4, and 2 mM CaCl2 to remove any blood, and the air spaces were lavaged with the same solution, minus MgSO4 and CaCl2 but supplemented with 6 mM glucose and 0.2 mM ethylene glycol tetraacetic acid (EGTA), to remove macrophages. The lung tissue was then minced, digested with elastase, filtered, and incubated for 1 h on IgG-coated petri dishes to remove contaminating cells. ATI were isolated by use of immunobeads (Invitrogen) coated with a mouse anti-rat T1α antibody. The ATI were cultured on glass in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium, 10% fetal bovine serum, 1% penicillin, and 1% ampicillin.

Live Cell F-Actin Imaging

Details of the Lifeact-GFP construct have been discussed previously (35). Lifeact is a 17-amino acid peptide, which associates with F-actin without altering actin dynamics (35). ATI (day 4 postisolation) were transfected with a Lifeact-GFP construct (pEGFP-N1 vector) using either FuGENE (Roche Applied Sciences, Indianapolis, IN), or Xfect (Clontech Laboratories, Mountain View, CA) reagents. The construct was a generous gift from Dr. Roland Wedlich-Soldner (Max Plank Institute, Martinsried, Germany).

Micropuncture Injury

A detailed description of the method for inducing focal PM injury and its validation can be found in Belete et al. (5). Briefly, cells were plated on glass-bottom dishes, washed, loaded with the desired label, and mounted onto a motorized stage on an Axiovert S100 TV fluorescence microscope (Zeiss, Thornwood, NY) equipped with a mercury short-arc lamp source. Cells were visualized with a ×100 oil immersion lens, and a Hamamatsu Orca-ER CCD digital camera was used to capture images every 0.6–0.8 s. A motorized microinjector (InjectMan; Eppendorf, Hauppauge, NY) was used to position a 1 μm-diameter glass needle (Femtotip, Eppendorf) within the field of view above the targeted cell. The cell was then stabbed at a 45° angle with an injury duration of 0.3 s.

Indicators of Cell Remodeling and Repair

PM integrity and time to repair.

PM integrity was inferred from the temporal decay in calcein AM fluorescence following micropuncture and was validated through exclusion of propidium iodide (5 μg/ml), which was applied 2 min after injury. Calcein AM diffuses freely throughout the cytosol and as such provides information about solute exchange across a PM wound (43). Cultured ATI between days 5 and 7 following isolation were loaded with 1 μM of calcein AM for 1 h at 37°C. Cells were then washed and injured in isotonic rodent Ringer solution, which contained 138 mm NaCl, 2.7 mm KCl, 1.06 mm MgCl2, 5.6 mm d-glucose, 12.4 mm HEPES, and 1.8 mM Ca2+ with a pH of 7.25 and were allowed to equilibrate for 10 min. A subset of experiments was performed in calcium-free rodent Ringer's solution supplemented with 0.1 mM EGTA to verify that repair was calcium dependent. Another set of experiments examined calcein loaded ATI that were incubated for 2 h prior to injury with 0.5 μM or 1 μM jasplakinolide, respectively. These experiments were to test the effects of cytoskeletal prestress and remodeling on the probability of repair. After transferring the cells onto the imaging system, we recorded the baseline fluorescence and identified cells with stable baseline readings. Individual cells were then injured as described above. The rate of fluorescence decay of wounded cells with stable baseline readings was analyzed (Fig. 1). As established in preliminary experiments we determined that a decay threshold of 0.04%/s was associated with a 4% false positive wound repair rate in ATI (5).

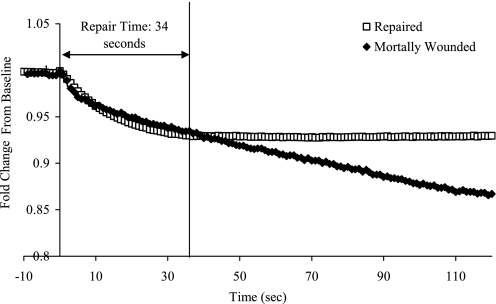

Fig. 1.

Characteristic calcein AM fluorescence intensity curves of a repaired (□) and mortally injury (♦) alveolar epithelial type I cell (ATI). At time 0, the micropuncture injury was applied, and the corresponding response was recorded for a minimum of 2 min. Repaired ATI show intensity decay to a point where the values stabilize, whereas intensity for mortally wounded cells continued to decay. The decay rate at 2 min in independently confirmed mortally wounded cells was used to set a threshold decay rate (−0.04%/s) to determine when plasma membrane (PM) integrity was once again restored. The cell is classified as repaired when its fluorescence decay goes below this threshold, and the time to repair can be calculated from this time point. In this example the repaired cell restored PM integrity 34 s after injury.

Actin remodeling.

Lifeact-GFP-transfected ATI were washed with isotonic rodent Ringer solution, imaged by use of epifluorescence (488 nm/510 nm), and injured as described above. Images were captured every 0.6–0.8 s for up to 8 min. Image analysis was performed by using ImageJ (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). To quantify the spatial and temporal pattern of actin remodeling, simple measurement of Lifeact-GFP fluorescence at or around the injury site was thoroughly insufficient. Accordingly, we developed a quantitative approach to measure actin remodeling. For each image, linescans were taken at 0°, 45°, 90°, and 135° through the injury site, generating an image with dimensions time vs. length along the linescan, and each pixel had a grayscale value that corresponded to Lifeact intensity. The resulting time series had characteristic profiles, which were defined by the following variables: time to initiation of F-actin repolymerization and peak actin expression, and actin remodeling time. Final values for each variable were expressed as an average across the four angular orientations for each experiment.

Cortactin labeling.

Cells were injured and fixed with 4% formaldehyde at 15-s intervals up to 180 s following micropuncture. The cells were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 and blocked with a buffer containing 5% goat serum, 5% glycerol, and 0.1% NaN3 for 1 h at 37°C. The samples were incubated with an anti-cortactin primary antibody overnight at 4°C at a 1:500 dilution in blocking buffer and subsequently labeled with Alexa Fluor 488. Immunostained samples were visualized by epifluorescence via a ×100 objective lens. The earliest time point where cortactin staining was identified in the vicinity of the wound was recorded for each time series of injured cells.

Accumulation of intracellular membrane-derived lipid at the wound site.

ATI were loaded with 5 μl of a 1 mg/ml solution of N-rhodamine phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) for 1 h at 37°C in isotonic rodent Ringer solution. Following the incubation, the cells were back exchanged by washing two times with 10% fetal bovine serum at room temperature to remove PM label. Following injury (as described above) images were captured every 0.6–0.8 s for up to 4 min. The time series of images were analyzed by using ImageJ (National Institutes of Health) via linescans taken at 0°, 45°, 90°, and 135° through the site of injury (as for the Lifeact-GFP analysis), and the resulting grayscale values were displayed as a function of space and time. A subset of cells were stained with both Lysotracker Green and N-rhodamine PE to determine whether the N-rhodamine PE label was associated with acidic organelles in ATI, which would indicate that N-rhodamine PE preferentially labels lysosomes in ATI (26).

Statistics

Median and interquartile range of repair times were calculated. Binary calculations were used to determine the probability of repair mean and standard error. All temporal measures of membrane trafficking (time for initiation of lipid recruitment) and actin remodeling (time for initiation of actin repolymerization, to peak actin expression, and remodeling time) were calculated as the means of the means of the four orientations, with the medians and interquartile range as a measure of the variability in the measurements.

RESULTS

Probability of Repair and Time to Repair

To determine whether a cell repaired, and how long it took after injury for restoration of PM integrity to occur, cytosol was fluorescently labeled with calcein AM. Calcein-containing cytosol exchanges with extracellular medium while the PM remains disrupted, resulting in a transient fluorescence decay that abated once PM integrity was again restored. In contrast, wounding cells in calcium-depleted media was associated with a progressive fluorescence decay, indicative of a failure to restore PM integrity (Fig. 1). The probability of successful wound repair following micropuncture injury was independently verified by nuclear exclusion of 10 nM propidium iodide. On the basis of this analysis, the probability of successful wound repair in ATI was 80 ± 6% (32/40 cells). The median time interval between micropuncture and the reestablishment of PM integrity was 18 s [interquartile range (IQR) = 11–39 s; Table 1]. This result provided the time frame for interpreting contemporary actin remodeling responses and their proposed effects on lipid-protein adhesion, membrane fluidity, and the force balance at the lipid bilayer wound edge.

Table 1.

Temporal characteristics of cellular repair in primary ATI

| Median | Interquartile Range | |

|---|---|---|

| Repair time (n = 32) | 18 s | 11–39 s |

| Probability of repair (n = 40) | Mean | 80% |

| SE: 6% | ||

| Initiation of lipid recruitment (n = 24) | 3 s | 2–5 s |

| Initiation of actin repolymerization (n = 28) | 22 s | 17–28 s |

| Time of initial cortactin expression (n = 10) | 90 s | 75–101 s |

| Time of peak actin expression (n = 17) | 100 s | 95–123 s |

| Actin remodeling time (n = 27) | 279 s | 213–303 s |

Repair times and probability of repair were determined through calcein AM dye loss. The time point of initial cortactin expression at the wound site was determined from 10 time series of injured, fixed, and immunostained alveolar epithelial type I cells (ATI). Since the data were not normally distributed, the medians and interquartile ranges are presented here.

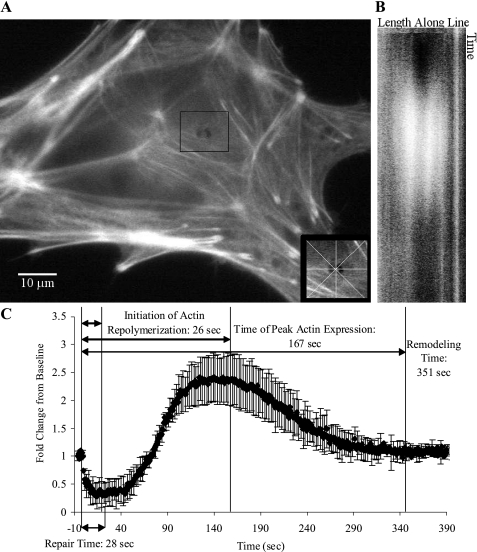

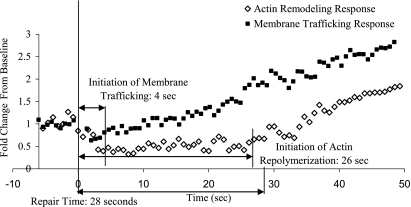

Characteristics of Actin Remodeling After Injury

Although a tightly woven subcortical actin network is a barrier to membrane trafficking (28), and hence wound repair, actin remodeling is considered a key step in the fusion between secretory vesicles with the plasma membrane (13). Lifeact-GFP was transfected in to ATI to visualize F-actin kinetics before and after the restoration of PM integrity. Images and results of a typical micropuncture experiment are shown in Fig. 2 and the spatial and temporal dynamics of F-actin kinetics are illustrated in Supplementary Movie S1 (the online version of this article contains supplemental data). Typically, following withdrawal of the micropipette, there was an immediate decay in the F-actin signal surrounding the puncture site, indicative of local actin depolymerization. In contrast, there was no consistent change in subcortical F-actin structure or fluorescence intensity remote from the wound site. Lifeact-GFP fluorescence intensity in the vicinity of the wound remained below baseline for a median of 22 s (IQR = 17–28), which is several seconds longer than the time it typically takes for PM integrity to be reestablished. The subsequent repolymerization response was marked by a 1.7 ± 0.8-fold increase in fluorescence intensity above baseline and peaked 105 s (IQR: 95–123 s) following PM repair (Table 1). Treating ATI with jasplakinolide, which favors F-actin polymerization, greatly inhibited repair, with 12 of 15 control ATI surviving the injury and only 5 of 15 (0.5 μM) or 1 of 10 (1 μM) jasplakinolide-treated ATI repaired the PM lesion.

Fig. 2.

Actin remodeling after injury in a repaired primary ATI. ATI were transfected with a Lifeact-green fluorescent protein (GFP) construct. Cells were injured with a 1-μm-diameter needle and fluorescence intensity was recorded for up to 8 min thereafter. Linescans were used to generate time vs. intensity images oriented at 0°, 45°, 90°, or 135° though the center of the puncture wound. A: representative image of a cell at the point the injury. Inset indicates the orientation of the 4 linescans through the wound. B: time map of the fluorescence intensity profiles of the linescan oriented 90° through the center of the wound. Note the increase in actin grayscale intensity (shown in white) during the repolarization phase. C: temporal changes in F-actin fluorescence intensity in the vicinity of the wound. Data represent means and standard deviations across the 4 linescan orientations and are expressed as fractions of their baseline preinjury values. Specific time points of interest including the initiation of actin repolymerization, peak actin expression, and actin remodeling time were determined by curve fitting. Initiation of actin repolymerization was defined by the initial inflection point of the intensity curve. The actin remodeling time was defined as the time between injury and the return of the fluorescence intensity tracing toward a stable value.

To rule out confounding effects of the Lifeact-GFP transfection on F-actin kinetics, we stained ATI with the commonly used phallotoxin phalloidin. Cells were rapidly fixed and stained anywhere between 10 and 120 s after injury. These experiments confirmed the temporal sequence of CSK depolymerization followed by late, exaggerated repolymerization in the vicinity of the wound (Supplementary Fig. S1). Failure to reestablish PM integrity was associated with a sustained loss of F-actin fluorescence at the wound site, which over time extended to the entire F-actin network. A typical example of F-actin kinetics in a mortally wounded cell is shown in Supplementary Fig. S2 and in Supplementary Movie S2.

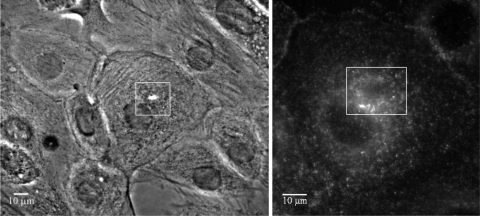

Spatiotemporal Profile of Cortactin

To support our interpretation of Lifeact fluorescence as surrogate of F-actin network density and local polymerization state we measured the initial appearance of the CSK nucleation factor cortactin at the wound site (12). We predicted that cortactin would accumulate in the vicinity of the wound before the zenith of Lifeact fluorescence, since it is an inducer of actively branching actin filaments. Consistent with our hypothesis in 10 of 12 experiments, cortactin was first detected within 90 s (IQR: 75–101 s, Table 1) following micropuncture (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Fixed, cortactin-labeled injured primary ATI. ATI were injured and fixed at 15-s time intervals after injury and then immunostained for cortactin. Left: phase image of a cell fixed 75 s after injury. Right: enlarged view of the immunostained injured cell. Note that cortactin had accumulated around the wound margins.

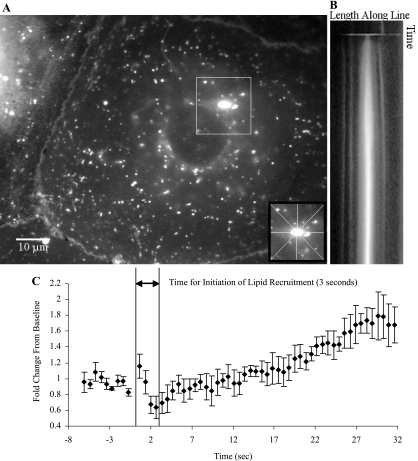

Accumulation of Endomembrane-derived Lipid at the Wound Site

It is well established that cell wounding results in exocytosis and accumulation of calcium-sensitive endosomes at injury sites (40). Accordingly, N-rhodamine PE was used to label, among others, lysosomes and late endosomes, considering that lysosomes are a likely source of endomembranes that get recruited to PM wounds (1, 20, 34). Colocalization studies between N-rhodamine PE and Lysotracker Green confirmed the lysosomal/late endosomal targeting of the lipid label (Supplementary Fig. S3). This allowed us to compare the temporal profiles of endomembrane-derived lipid accumulation and CSK remodeling in the vicinity of the wound. Since the micropipette-induced injury resembles a punch biopsy, there was a transient drop in N-rhodamine PE fluorescence intensity at the wound site followed by a quick recovery (See Fig. 4 and Supplementary Movie S3 for an example). Cells that ultimately repaired accumulated N-rhodamine PE within 4 s (Fig. 4 and Table 1), coincidental with actin depolymerization (Fig. 5). Some mortally wounded cells also recruited lipid to the wound (see Supplementary Fig. S4 and Supplementary Movie S4), but in contrast to cells with successful membrane repair, the accumulation of lipid label was always transient and lasted but a few seconds.

Fig. 4.

Accumulation of endomembrane-derived N-rhodamine phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) at the injury site of a repaired primary ATI. ATI were loaded with N-rhodamine PE for 1 h at 37°C and back exchanged to remove N-rhodamine PE from the PM. Cells were injured with a 1-μm-diameter needle and fluorescence intensity was recorded for up to 4 min. Following the experiment, linescans oriented at 0°, 45°, 90°, or 135° through the center of the wound were used to generate time-vs.-intensity images. A: representative image of the fluorescence intensity at the point the injury. Inset indicates the orientation of the 4 linescans through the wound site. B: image generated from the 90° linescan through the wound. Increasing grayscale values (white) reflect the accumulation of N-rhodamine PE at the site. Cell survival was determined through the exclusion of propidium iodide. C: temporal changes in N-rhodamine PE fluorescence intensity in the vicinity of the wound. Data represent means and standard deviations across the 4 linescan orientations and are expressed as fractions of their baseline preinjury values. The initial inflection in the intensity-time profile marks the initiation of lipid recruitment.

Fig. 5.

Comparison of actin remodeling and N-rhodamine PE accumulation responses during the initial 50 s after micropuncture in a primary ATI. Injury was applied after a 5-s baseline recording in ATI either labeled with N-rhodamine PE or transfected with the GFP-actin label Lifeact. Changes in signal intensity were quantified as previously described. The accumulation of endomembrane-derived PE starts at an earlier time point than actin repolymerization, which is typically delayed until after PM integrity is reestablished.

DISCUSSION

We have defined the spatial and temporal coordination between cytoskeletal remodeling and PM repair following a mechanical injury in ATI. We show that wounding by micropuncture causes a rapid depolymerization of the actin CSK near the wound site, associated with the accumulation of endomembrane-derived lipids. Both responses are sustained until PM integrity is reestablished, which occurs typically between ∼10 and 40 s following injury. Only thereafter does the actin CSK near the wound repolymerize, at a time at which the rate of endomembrane lipid accumulation begins to decrease. Translocation of cortactin to the injury site precedes the subsequent formation of a dense actin fiber network, which peaks between 60 and 90 s after successful PM repair. By 5 min, the actin network surrounding the micropuncture site is generally indistinguishable from that of uninjured cells. In contrast, in mortally wounded cells the accumulation of endomembrane-derived lipids is not sustained and failure to reestablish membrane integrity precludes the subsequent CSK polymerization.

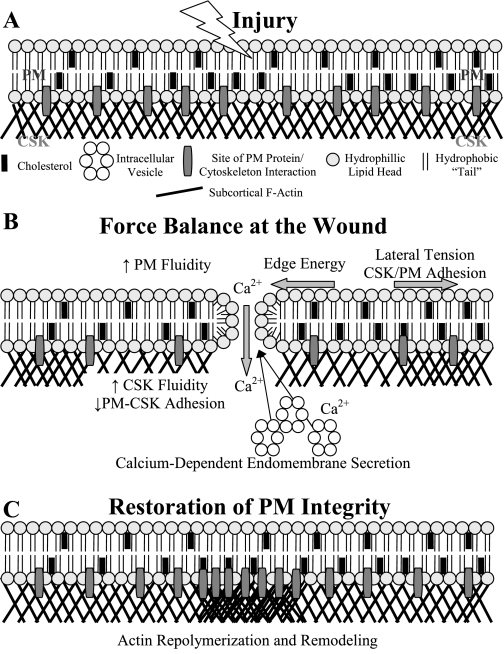

To interpret the mechanisms underlying the above sequence of events (schematically represented in Fig. 6), we must first consider the forces that drive a lipid bilayer defect to closure and the biophysical interactions between cytoskeletal proteins and PM lipids on them. The self-healing properties of the lipid bilayer are regulated by the edge energy at the margins of PM wounds following injury (Fig. 6, A and B). Edge energy is determined by the orientation of hydrophilic lipid heads relative to the hydrophobic fatty acid chains (14, 52). Exposure of fatty acid chains at the lipid-water interface generates a high-energy state, which favors persistence of the PM defect, whereas their submersion under tilted lipid heads favors PM resealing. Balancing the edge energy are the lateral tension in the plane of the PM and decreased fluidity on account of molecular interactions between lipids and proteins within and across the bilayer (Fig. 6B). We and others had previously shown that, compared with adhesive PM-CSK interactions, the lateral tension in the plane of the bilayer is relatively small (32, 37). The adhesive force that keeps the lipid bilayer in apposition with the subcortical CSK is largely determined by weak molecular interactions between the lipids of the inner bilayer leaflet and CSK-associated proteins (15, 31, 38). Transmembrane proteins that are anchored to the CSK are also likely to contribute to adhesion force particularly in the vicinity of focal contact points between the cell and extracellular matrix. The adhesion force is subject to regulation by membrane-derived enzymes, which target phosphoinositide metabolism, and is therefore exquisitely sensitive to the polymerization state of the subcortical actin CSK (36).

Fig. 6.

Proposed model for the restoration and repair of PM lesions following focal injury. A mechanical injury (A) to the intact PM of epithelial cells is known to result in an influx of calcium into the cell (40), which induces calcium-dependent endomembrane secretion to the injury site (1, 27). Concurrent with this secretion response, the subcortical cytoskeleton (CSK) depolymerizes to remove a barrier to endomembrane trafficking to the wound site (28) and increase the fluidity of the PM by reducing the PM-CSK adhesive interactions (B). The edge energy favoring the closure of the wound is resisted by lateral tension in the PM and the PM-CSK adhesive interactions, whereas the increase in membrane fluidity resulting from the CSK depolymerization promotes closure of the wound (B). CSK depolymerization also reduces the PM-CSK adhesive interaction force resisting lesion closure. It is only after restoration of PM integrity that the wound site is repolymerized and then remodeled (C).

The primary contribution of our study to the topic of cell repair is the detailed account of the temporal coordination between CSK polymerization state and the reestablishment of bilayer integrity. Specifically, Lifeact fluorescence intensity near the wound decreased immediately upon injury and did not recover until after membrane integrity had been reestablished (schematically represented in Fig. 6, C and D). The potential role of actin repolymerization in repair in general falls into two categories, with some studies showing that actin filament disassembly is a sufficient final trigger for exocytosis (29), whereas some other groups have suggested that F-actin synthesis could be the final trigger for membrane fusion after exocytosis (13). Our observation suggests that the degree of CSK polymerization and hence the adhesive force between lipid bilayer and CSK near the wound remain low as long as there is a bilayer defect. First, the smaller number of lipid molecules that are immobilized by cytoskeletal interactions raises membrane fluidity, thereby reducing an edge energy opposing closure force (Fig. 6B). Second, a depolymerized CSK facilitates the transit of calcium-sensitive endomembranes, such as lysosomes, to the wound, thereby enriching the defective bilayer with substrate, as well as altering its lipid composition through the local release of acidic proteases (41). Both mechanisms promote repair.

Trepat et al. (48) demonstrated that the CSK of cells transiently fluidizes (softens) in response to a deforming stress and considered this agitation response a universal property of soft glassy materials. They also pointed out that glassy dynamics of the CSK, i.e., the respective rates of fluidization and resolidification, scaled with CSK tension (prestress), but that the responsible molecular mechanisms were not at all understood. We show that the subcortical actin network of ATI in the vicinity of micropuncture wounds also undergoes a glass transition, i.e., the network fluidized locally followed by a repolymerization response, which peaked 100 s later. Although earlier reports had suggested that in fibroblasts wounding led to a global decrease in PM tension on account of global actin remodeling, we were unable to detect a systematic change in Lifeact fluorescence remote from the wound site (45, 46).

Because our findings suggested that the polymerization state of the CSK by virtue of its effect on adhesive interactions between CSK and PM was a critical determinant of membrane repair, we tested the effects of the “actin stabilizer” jasplakinolide on PM resealing. Jasplakinolide reduces the critical concentration of actin required for nucleation and is associated with increased CSK stiffness and tension (9). As expected, the pretreatment of ATI with jasplakinolide significantly reduced the probability of cell repair and did so in a dose-dependent manner (28). It should be noted that pretreatment with jasplakinolide did not prevent the initial decay in Lifeact fluorescence near the puncture wound. This is in keeping with Trepat et al.'s (48) prior observation, that jasplakinolide-treated cells also fluidize in response to a stretch. The mechanisms by which jasplakinolide reduces the probability of micropuncture wound repair may nevertheless be attributed to its effects on glassy dynamics, namely 1) a more rapid resolidification response, impairing the lateral mobility of the PM lipid bilayer and 2) an increase in the size of the actin network lesion on account of greater local tension.

We have shown that treatment with jasplakinolide before injury prevents repair in ATI, indicating that its specific mechanism of modification to the subcortical CSK has a negative impact on repair. Interpreting this result in the context of the described repair model is challenging, since the specific negative effect of jasplakinolide on PM lesion repair is difficult to judge. It promotes F-actin polymerization, in which an increase in subcortical CSK would be believed to restrict the ability of endomembrane compartments to traffic to and fuse with the PM (13, 28). Jasplakinolide treatment also increases the baseline cell stiffness, which may promote expansion of the wound after the initial application of the wounding stimulus, but, interestingly, treated cells maintain an ability to fluidize in response to mechanical stress (48), indicating that an injured, jasplakinolide-treated ATI could still have an ability to depolymerize after injury. Jasplakinolide also reduces the critical concentration of actin required for nucleation (9), which may favor actin repolymerization of the wound site before restoration of PM integrity. To make clear conclusions on how manipulation of the subcortical CSK could impact PM lesion repair would require careful examination of all of these potential factors.

Lifeact is a 17-amino acid peptide corresponding to an epitope of the actin binding protein (Abp) 140, which has been purified from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Although Abp140 mediates the cross-linking of F-actin bundles in budding yeast (2), the Lifeact-GFP construct was shown to have little impact on actin kinetics during neuronal polarization, lamellipodial flow, or leukocyte chemotaxis (35). This makes Lifeact an attractive label to study actin dynamics in living cells. It should be noted that Lifeact does not bind to cofilin-bound actin rods, which have been observed in neurons exposed to oxidative stress (30), and which form as a consequence of local ATP depletion. Specifically, the actin depolymerizing factor/cofilin complex promotes rapid depolymerization and severing of actin filaments (36).

We had previously reported that up to 60% of ATI repair micropuncture wounds within 40 s; our measurements here corroborate these findings (5). To this end we labeled the cytosol with calcein AM, which, once esterified, becomes membrane impermeable. We assumed that a PM defect represents a path for fluid exchange between cytosol and media and would therefore be associated with a decline in calcein AM fluorescence. We had shown that label decay profiles were both sensitive and specific markers of PM bilayer integrity and yielded repair time estimates comparable to ones recently reported in rat kangaroo kidney epithelial cells (44). Given the affinity of water to cytoskeletal proteins (33), we had wondered whether an intense actin polymerization response might retard the fluid exchange across a membrane bilayer defect but rejected this hypothesis once we realized that the actin network did not begin to polymerize until several seconds after a stable calcein fluorescence profile suggested that bilayer integrity had been restored.

Since repair of micropuncture wounds involves site-directed exocytosis of calcium-sensitive endomembrane compartments (27, 40), we predominantly labeled lysosomes and endosomes with N-rhodamine PE and monitored their translocation to the injury site. Golgi-derived endomembrane translocated to the location of a mechanical injury in a microtubule-dependent manner, but repair was inhibited only after an additional injury, indicating that microtubules are required for repair when endosomal trafficking from distant cellular compartments is required (44). N-rhodamine PE-labeled lysosome and late endosome compartments (Supplementary Fig. S3) accumulated at the wound site within seconds whereby fluorescence intensity continued to increase albeit at a reduced rate following bilayer repair and repolymerization of the surrounding CSK (Fig. 2 and 4), perhaps indicating that both predocked and distant endosomal compartments contribute to the endosomal accumulation at the wound. We did not study the fate of N-rhodamine PE-labeled lysosomes/endosomes or of any other lipid label following accumulation at the PM. This is a limitation of our study insofar as recent evidence suggests that endocytosis is a necessary step in PM repair following either chemical or mechanical insults (19, 41). At present we have therefore not enough information to integrate endocytic and exocytic mechanisms as determinants of edge energy, membrane fluidity, and thus the probability and timing of bilayer repair.

Conclusions and Future Directions

We provide the first report of actin dynamics following mechanical wounding in living ATI. Our observations establish that the PM of ATI, which frequently experience stress failure in edematous, mechanically ventilated lungs, readily repair relatively large wounds. We show that membrane repair is aided by the depolymerization of the actin CSK in the vicinity of the wound and that it is associated with the transport of endomembrane-derived lipids to the injury site. On the basis of these observations we infer that CSK remodeling in effect raises PM fluidity and postulate that both endocytic and exocytic mechanisms establish a more favorable force balance between edge energy and PM/CSK adhesion. This conceptual framework suggests a number of testable hypotheses about opportunities to promote or retard cell repair by manipulating the lipid composition of the PM or by targeting CSK remodeling.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant HL 63178 (R. D. Hubmayr) and the Mayo Graduate School.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise are declared by the author(s).

Supplementary Material

REFERENCES

- 1.Andrews NW. Regulated secretion of conventional lysosomes. Trends Cell Biol 10: 316–321, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Asakura T, Sasaki T, Nagano F, Satoh A, Obaishi H, Nishioka H, Imamura H, Hotta K, Tanaka K, Nakanishi H, Takai Y. Isolation and characterization of a novel actin filament-binding protein from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Oncogene 16: 121–130, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bachofen M, Weibel ER. Alterations of the gas exchange apparatus in adult respiratory insufficiency associated with septicemia. Am Rev Respir Dis 116: 589–615, 1977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bachofen M, Weibel ER. Structural alterations of lung parenchyma in the adult respiratory distress syndrome. Clin Chest Med 3: 35–56, 1982 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Belete HA, Godin LM, Stroetz RW, Hubmayr RD. Experimental models to study cell wounding and repair. Cell Physiol Biochem 25: 71–80, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bernatchez PN, Sharma A, Kodaman P, Sessa WC. Myoferlin is critical for endocytosis in endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 297: C484–C492, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bi GQ, Alderton JM, Steinhardt RA. Calcium-regulated exocytosis is required for cell membrane resealing. J Cell Biol 131: 1747–1758, 1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bilek AM, Dee KC, Gaver DP., 3rd Mechanisms of surface-tension-induced epithelial cell damage in a model of pulmonary airway reopening. J Appl Physiol 94: 770–783, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bubb MR, Spector I, Beyer BB, Fosen KM. Effects of jasplakinolide on the kinetics of actin polymerization. An explanation for certain in vivo observations. J Biol Chem 275: 5163–5170, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cerny J, Feng Y, Yu A, Miyake K, Borgonovo B, Klumperman J, Meldolesi J, McNeil PL, Kirchhausen T. The small chemical vacuolin-1 inhibits Ca2+-dependent lysosomal exocytosis but not cell resealing. EMBO Rep 5: 883–888, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen J, Chen Z, Narasaraju T, Jin N, Liu L. Isolation of highly pure alveolar epithelial type I and type II cells from rat lungs. Lab Invest 84: 727–735, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cosen-Binker LI, Kapus A. Cortactin: the gray eminence of the cytoskeleton. Physiology (Bethesda) 21: 352–361, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eitzen G. Actin remodeling to facilitate membrane fusion. Biochim Biophys Acta 1641: 175–181, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Evans E, Heinrich V, Ludwig F, Rawicz W. Dynamic tension spectroscopy and strength of biomembranes. Biophys J 85: 2342–2350, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fehon RG, McClatchey AI, Bretscher A. Organizing the cell cortex: the role of ERM proteins. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 11: 276–287, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gajic O, Lee J, Doerr CH, Berrios JC, Myers JL, Hubmayr RD. Ventilator-induced cell wounding and repair in the intact lung. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 167: 1057–1063, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gonzalez R, Yang YH, Griffin C, Allen L, Tigue Z, Dobbs L. Freshly isolated rat alveolar type I cells, type II cells, and cultured type II cells have distinct molecular phenotypes. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 288: L179–L189, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grembowicz KP, Sprague D, McNeil PL. Temporary disruption of the plasma membrane is required for c-fos expression in response to mechanical stress. Mol Biol Cell 10: 1247–1257, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Idone V, Tam C, Goss JW, Toomre D, Pypaert M, Andrews NW. Repair of injured plasma membrane by rapid Ca2+-dependent endocytosis. J Cell Biol 180: 905–914, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McNeil PL. Repairing a torn cell surface: make way, lysosomes to the rescue. J Cell Sci 115: 873–879, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McNeil PL, Ito S. Gastrointestinal cell plasma membrane wounding and resealing in vivo. Gastroenterology 96: 1238–1248, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McNeil PL, Ito S. Molecular traffic through plasma membrane disruptions of cells in vivo. J Cell Sci 96: 549–556, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McNeil PL, Khakee R. Disruptions of muscle fiber plasma membranes. Role in exercise-induced damage. Am J Pathol 140: 1097–1109, 1992 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McNeil PL, Steinhardt RA. Loss, restoration, and maintenance of plasma membrane integrity. J Cell Biol 137: 1–4, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McNeil PL, Vogel SS, Miyake K, Terasaki M. Patching plasma membrane disruptions with cytoplasmic membrane. J Cell Sci 113: 1891–1902, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mirnikjoo B, Balasubramanian K, Schroit AJ. Suicidal membrane repair regulates phosphatidylserine externalization during apoptosis. J Biol Chem 284: 22512–22516, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miyake K, McNeil PL. Vesicle accumulation and exocytosis at sites of plasma membrane disruption. J Cell Biol 131: 1737–1745, 1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miyake K, McNeil PL, Suzuki K, Tsunoda R, Sugai N. An actin barrier to resealing. J Cell Sci 114: 3487–3494, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Muallem S, Kwiatkowska K, Xu X, Yin HL. Actin filament disassembly is a sufficient final trigger for exocytosis in nonexcitable cells. J Cell Biol 128: 589–598, 1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Munsie LN, Caron N, Desmond CR, Truant R. Lifeact cannot visualize some forms of stress-induced twisted F-actin. Nat Methods 6: 317, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nambiar R, McConnell RE, Tyska MJ. Control of cell membrane tension by myosin-I. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 11972–11977, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oeckler RA, Walters BJ, Stroetz RW, Hubmayr RD. Osmotic pressure alters alveolar epithelial cell plasma membrane mechanics via PIP2 and cytoskeletal rearrangement (Abstract). Am J Respir Crit Care Med 179: A2499, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pollack GH. Cells, Gels and the Engines of Life. Seattle, WA: Ebner, 2001, p. 305 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reddy A, Caler EV, Andrews NW. Plasma membrane repair is mediated by Ca2+-regulated exocytosis of lysosomes. Cell 106: 157–169, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Riedl J, Crevenna AH, Kessenbrock K, Yu JH, Neukirchen D, Bista M, Bradke F, Jenne D, Holak TA, Werb Z, Sixt M, Wedlich-Soldner R. Lifeact: a versatile marker to visualize F-actin. Nat Methods 5: 605–607, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saarikangas J, Zhao H, Lappalainen P. Regulation of the actin cytoskeleton-plasma membrane interplay by phosphoinositides. Physiol Rev 90: 259–289, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sheetz MP, Dai J. Modulation of membrane dynamics and cell motility by membrane tension. Trends Cell Biol 6: 85–89, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sheetz MP, Sable JE, Dobereiner HG. Continuous membrane-cytoskeleton adhesion requires continuous accommodation to lipid and cytoskeleton dynamics. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct 35: 417–434, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Slutsky AS, Tremblay LN. Multiple system organ failure. Is mechanical ventilation a contributing factor? Am J Respir Crit Care Med 157: 1721–1725, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Steinhardt RA, Bi G, Alderton JM. Cell membrane resealing by a vesicular mechanism similar to neurotransmitter release. Science 263: 390–393, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tam C, Idone V, Devlin C, Fernandes MC, Flannery A, He X, Schuchman E, Tabas I, Andrews NW. Exocytosis of acid sphingomyelinase by wounded cells promotes endocytosis and plasma membrane repair. J Cell Biol 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Terasaki M, Miyake K, McNeil PL. Large plasma membrane disruptions are rapidly resealed by Ca2+-dependent vesicle-vesicle fusion events. J Cell Biol 139: 63–74, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thorpe WP, Toner M, Ezzell RM, Tompkins RG, Yarmush ML. Dynamics of photoinduced cell plasma membrane injury. Biophys J 68: 2198–2206, 1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Togo T. Disruption of the plasma membrane stimulates rearrangement of microtubules and lipid traffic toward the wound site. J Cell Sci 119: 2780–2786, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Togo T, Alderton JM, Bi GQ, Steinhardt RA. The mechanism of facilitated cell membrane resealing. J Cell Sci 112: 719–731, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Togo T, Krasieva TB, Steinhardt RA. A decrease in membrane tension precedes successful cell-membrane repair. Mol Biol Cell 11: 4339–4346, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tremblay LN, Slutsky AS. Ventilator-induced injury: from barotrauma to biotrauma. Proc Assoc Am Physicians 110: 482–488, 1998 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Trepat X, Deng L, An SS, Navajas D, Tschumperlin DJ, Gerthoffer WT, Butler JP, Fredberg JJ. Universal physical responses to stretch in the living cell. Nature 447: 592–595, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Uhlig S. Ventilation-induced lung injury and mechanotransduction: stretching it too far? Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 282: L892–L896, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang S, Hubmayr RD. Type I alveolar epithelial phenotype in primary culture. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2011. January 21 [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ware LB, Matthay MA. The acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 342: 1334–1349, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Weaver JC, Chizmadzhev YA. Theory of electroporation: a review. Bioelectrochem Bioenerg 41: 135–160, 1996 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.