Abstract

We present plasma membrane (PM) internalization responses of type I alveolar epithelial cells to a 50 mosmol/l increase in tonicity. Our research is motivated by interest in ATI repair, for which endocytic retrieval of PM appears to be critical. We validated pharmacological and molecular tools to dissect the endocytic machinery of these cells and used these tools to test the hypothesis that osmotic stress triggers a pathway-specific internalization of PM domains. Validation experiments confirmed the fluorescent analogs of lactosyl-ceramide, transferrin, and dextran as pathway-specific cargo of caveolar, clathrin, and fluid-phase uptake, respectively. Pulse-chase experiments indicate that hypertonic exposure causes a downregulation of clathrin and fluid-phase endocytosis while stimulating caveolar endocytosis. The tonicity-mediated increase in caveolar endocytosis was associated with the translocation of caveolin-1 from the PM and was absent in cells that had been transfected with dominant-negative dynamin constructs. In separate experiments we show that hypertonic exposure increases the probability of PM wound repair following micropuncture from 82 ± 4 to 94 ± 2% (P < 0.01) and that this effect depends on Src pathway activation-mediated caveolar endocytosis. The therapeutic and biological implications of our findings are discussed.

Keywords: acute lung injury, caveolar endocytosis, cell repair, osmotic pressure

the alveolar epithelium is composed of two cell populations, namely the very large thin type I cells (ATI) (38) and the cuboidal secretory type II cells (ATII) (41). In the acutely injured lung many ATI and to some extent ATII die by mechanisms of necrosis and apoptosis whereby the resulting alveolar wounds become coated with a fibrin-rich matrix (40). In addition, the derecruitment of lung units and the accumulation of liquid in alveolar spaces predisposes ATI and ATII to mechanical injury by overdistension and interfacial stress (4). Although physical cell wounding undoubtedly contributes to ATI necrosis, many alveolar epithelial cells repair their PM wounds and remain viable, albeit in a stressed state (37). When tested in reduced systems, this stress manifests as activation of early stress response genes and the release of proinflammatory cytokines (7).

Cell repair requires the coordinated interplay between membrane trafficking and cytoskeletal remodeling. Cell wounding-induced membrane trafficking provides the lipid substrate for plasma membrane (PM) repair and involves both exocytic and endocytic trafficking pathways (13, 20, 34). The relative contributions of each to PM repair and their coordination are poorly understood. Moreover, there is relatively little specific information on ATI repair since these cells have traditionally proven difficult to harvest and to maintain with sufficient purity in culture. To the extent to which lessons from other cell wounding models apply to ATI, one should expect that wounding will trigger the fusion and exocytosis of calcium-sensitive endomembranes, foremost lysosomes, followed by a polymerization response of the cytoskeleton near the lesion (20). Recent observations on cells exposed to pore-forming toxins or subjected to large mechanical wounds have underscored the importance of sphingomyelinase-mediated ceramide generation in facilitating cell repair (34). This mechanism links lysosomal exocytosis, the source of sphingomyelinase, with ceramide-mediated endocytic PM remodeling. The extent to which the repair response involves specific endocytosis pathways, such as clathrin, caveolar, and/or fluid-phase pathways, however, is not known.

We present data on the membrane trafficking responses of ATI upon exposure to osmotic stress. Our interest in this topic is rooted in the belief that cell wounding and repair are important drivers of the innate immune response of the injured lung (24). We had previously identified hypertonic cell conditioning as an intervention that prevents epithelial deformation injury and promotes PM repair in rodent lungs (25) To gain insights into osmotic stress-induced PM remodeling, specifically in ATI, we tested and validated molecular and pharmacological tools to dissect the endocytic machinery of these cells. We subsequently used these tools to test the hypothesis that osmotic stress triggers a pathway-specific internalization of PM domains and that this response is integral to PM wound repair. Our observations on ATI indicate that osmotic stress causes a transient downregulation of clathrin and fluid-phase endocytosis, while stimulating caveolar endocytosis. Moreover, we show that the tonicity-induced increase in caveolar endocytosis is mediated by Src pathway activation and is associated with improved cell repair. The biological implications of these findings will be discussed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids, Antibodies, and Reagents

These are listed in the electronic data supplement (the online version of this article contains supplemental data).

Cell Isolation and Culture

Rat ATIs were isolated by immunoselection for T1alpha (39). ATIs were seeded on glass coverslips and cultured in high-glucose DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 200 units (μg)/ml of penicillin and streptomycin and maintained in a 5% CO2 humidified 37° incubator. Cells were studied 5–7 days after harvest.

Micropuncture Injury

A detailed description of the method for inducing focal PM injury and its validation can be found in Belete et al. (1) Briefly, cells were plated on glass-bottom dishes, washed, loaded with the desired label, and mounted onto a motorized stage on an Axiovert S100 TV fluorescence microscope (Zeiss, Thornwood, NY) equipped with a mercury short-arc lamp source. Cells were visualized with a ×100 oil immersion lens, and a Hamamatsu Orca-ER CCD digital camera was used to capture images every 0.6 to 0.8 s. A motorized microinjector (InjectMan; Eppendorf, Hauppauge, NY) was used to position a 1 μm diameter glass needle (Femtotip, Eppendorf) within the field of view above the targeted cell. The cell was then stabbed at a 45° angle with injury duration of 0.3 s. In some experiments, cells were preincubated with the Src-kinase inhibitor PP2 (10 μM) for 1 h at 37°C.

Indicators of Cell Remodeling and Repair

PM integrity was inferred from the temporal decay in calcein AM fluorescence (Molecular Probes-Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) following micropuncture, and was validated through exclusion of propidium iodide (5 μg/ml), which was applied 2 min after injury. Calcein AM diffuses freely throughout the cytosol and as such provides information about solute exchange across a PM wound (36). Cultured ATIs between days 5 and 7 following isolation were loaded with 1 μM of calcein AM for 1 h at 37°C. Cells were then washed in isotonic rodent Ringer solution, which contained 138 mm NaCl, 2.7 mm KCl, 1.06 mm MgCl2, 5.6 mm d-glucose, 12.4 mm HEPES, and 1.8 mM Ca2+ with a pH of 7.25 and were allowed to equilibrate for 10 min. After transfer of the cells onto the imaging system, baseline fluorescence was recorded and cells with stable baseline readings were identified. Individual cells were then injured as described above. The rate of fluorescence decay of wounded cells with stable baseline readings was analyzed. As established in preliminary experiments, we determined that a decay threshold of 0.04%/s was associated with a 4% false positive wound repair rate in ATIs (1). The osmolarity of the Ringer solution used to treat the cells was 240, 290, and 340 mosM, respectively.

Pulse-Chase Experiments

BODIPY-lactosyl ceramide (LacCer), AF594/488/647-transferrin (Tfn), and AF 594/488/647-dextran (Dex) served as pathway-specific cargo in pulse-chase experiments as previously described (17). In brief, cells were washed with HEPES minimum essential medium (HMEM) and incubated with either BODIPY-LacCer (2.5 μM) or AF594/488/647-Tfn (5 μg/ml) at 10° for 30 min to prelabel the PM. For experiments involving Tfn, cells were first serum starved for 2 h at 37° to upregulate the Tfn receptor. To assess the rate of internalization of prelabeled endocytic markers cells were transferred to a 37° water bath for a given time period. Excess PM-bound BODIPY-LacCer was removed by back exchange at 10° with 5% fatty acid-free BSA-HMEM, so that internalized LacCer could be identified on epifluorescence images (2). For the same reason, PM-bound Tfn was acid stripped on ice for 15–20 s with acetic acid-HMEM (pH 3.0). Experiments involving the fluid-phase marker Dex did not require preincubation at 10°. Cells were labeled at 37° with 100 μg/ml prewarmed Dex and gently washed and imaged at the specified times.

Comparisons of pathway-specific uptake kinetics between cells exposed to isotonic and hypertonic media were carried out in parallel. At the time points of interest (1, 3, 5, and 10 min following hypertonic challenge), cells labeled with LacCer were fixed on ice with 3% paraformaldehyde and 0.02% glutaraldehyde for 15 min, and the PM-bound BODIPY-LacCer removed by back exchange. Cells labeled with Tfn were acid stripped and then fixed as described above. Cells labeled with Dex were washed with ice-cold HMEM and subsequently fixed.

Colocalization Assay

Colocalization assays were carried out to validate the specificity of pathway markers LacCer, Tfn, and Dex. To eliminate confounding “bleedover” of BODIPY-LacCer green into the red channel, we used AF647 far-red-tagged Dex or Tfn in the respective colabeling studies. Experiments were restricted to 1 min, after which cells were placed on ice, to guard against merging between pathways.

Use of Dominant-Negative Constructs

To distinguish between the responses of fluid-phase and clathrin-dependent endocytic pathways, ATI were genetically modified by overexpressing dominant-negative pathway-specific constructs. ATI were transfected by using Lipofectamine with either dominant-negative construct DN Cdc42 or DN AP180 following the manufacturer's instruction (2). In studies of DN AP180 protein overexpression, cells were cotransfected with DN AP180 and pDsRed2-Nuc, so that the nuclei of transfected cells could be identified by their red color (32). In these studies the endocytic cargo molecules (AF488-Tfn, AF488-Dex, and BODIPY-LacCer) were labeled green. To evaluate the effects of Cdc42 on Tfn and Dex uptake, the cells were transfected with DN Cdc42-GFP. The cargo molecules (AF594-Tfn and AF594-Dex) were labeled red. In experiments with BODIPY-LacCer, which emits a green fluorescence, cells were transfected with DN Cdc42-mRed. To distinguish between caveolar and noncaveolar uptake of LacCer, a dominant-negative dynamin construct, DN dynamin, was used to cotransfect ATI with pDsRed2-Nuc. Inhibition of LacCer uptake in DN dynamin transfected cells served to eliminate osmotic stress-mediated bilayer “flipping” as confounding internalization route of this caveolar pathway marker.

mRed-Cav-1 Overexpression

Studies on several different cell lines had suggested that BODIPY-LacCer is primarily internalized by caveolar endocytosis (2, 32). To confirm this finding in ATI, cells were genetically modified to overexpress mRed-tagged caveolin-1 (Cav-1) so that colocalization with BODIPY-LacCer could be measured. The colocalization of mRed Cav-1 with the clathrin and fluid-phase endocytosis specific cargo molecules AF488-Tfn and AF488-Dex was also analyzed to determine specificity.

Pharmacological Inhibitors of Endocytosis

To test the pathway specificity of pharmacological interventions ATI were pretreated at 37°C with HMEM containing 4-amino-5-(4-chlorophenyl)-7-(t-butyl)pyrazolo[3,4-d]pyramidine (PP2, 10 μM), Clostridium difficile toxin B (100 μM), genistein (200 μM) for 60 min and chlorpromazine (CPZ, 8 μg/ml), nystatin (25 μg/ml), or methyl β-cyclodextrin (mβ-CD, 200 μM) for 30 min, respectively (2, 29). Inhibitors were then present throughout all subsequent steps of the experiments.

Cav-1 Translocation

PM-associated Cav-1 was identified by immunostaining of methanol cold (−20°C) fixed cells with the antibody (M0TL43420), which has a PM Cav-1 pool preference, as described by Pol et al. (27). To identify total Cav-1, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 15–30 min, permeabilized with 0.1% saponin, and the antibody (RbTL) with affinity to all fractions of Cav-1 was added. PM labeling was quantified with fluorescence microscopy, whereas total Cav-1 labeling was assessed by total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) microscopy. In some experiments, cells were pretreated with the Src-kinase inhibitor PP2 (10 μM) for 1 h at 37°C.

Src Pathway Activation

ATI cells were pretreated with the Src-kinase inhibitor PP2 (10 μM) or placebo for 1 h at 37°C and subsequently challenged with hypertonic saline (340 mosM) for 30, 60, and 120 s, respectively. Cell lysate was collected with RIPA lysis buffer (1% NP-40, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 150 mM NaCl, 0.01 M Na2HPO4, 1 mM NaF, 5 mM Na3VO4, 1 mM PMSF, 10 μg/ml of each aprotinin and leupeptin, pH 7.2). Bound phospho Src (P-Src) and total Src (T-Src) were analyzed by SDS-PAGE separation on a 10% polyacrylamide gel, followed by immunoblotting with a polyclonal antibody against P-Src (at phosphorylation site pY418) and a monoclonal antibody against T-Src at the size of 59 kDa. The phosphorylation of Src was quantified by use of Quantity One 1-D Analysis Software (Bio-Rad) and normalized by T-Src and β-actin loading controls.

Image Analysis and Statistics

Epifluorescence images were acquired with a Olympus AX70 microscope and analyzed via the MetaMorph image processing program (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) (2). TIRF imaging was carried out by use of an Olympus IX70 microscope with an Olympus TIRF module. More than 10 image fields and 30–50 cells were analyzed per experiment. All photomicrographs in a given experiment were exposed and processed identically for a given fluorophore. For colocalization studies, no bleedover between microscope channels was observed at the concentration and exposure setting used. The data presented in each treatment group represent the average fluorescence values normalized by the values of the corresponding matched controls. Data are displayed as means and standard deviations. Statistical significance of differences between treatments, individual labels, and time from challenge was tested via a one-way ANOVA with the Tukey-Kramer multiple-comparison test on a JMP program (SAS, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

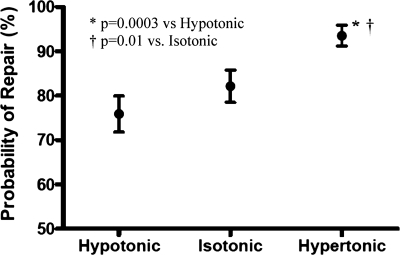

Hypertonic Exposure Increases the Probability of PM Wound Repair in ATI

ATI were injured with a 1-μm-diameter glass pipette. Subsequent PM repair was inferred from the fluorescence decay patterns of the cytosolic label calcein. Figure 1 shows the probability of repair, i.e., the percentage of cells that successfully repaired micropuncture wounds, when exposed to media of different tonicities, namely, hypotonic (240 mosM), isotonic (290 mosM), and hypertonic (340 mosM). The probability of repair was significantly greater for ATI exposed to hypertonic media (101 of 108 cells, 94 ± 2%; P < 0.01) than those exposed to either isotonic (92 of 112 cells; 82 ± 4%) or hypotonic media (85/112; 76 ± 4%), respectively.

Fig. 1.

Effect of osmotic stress on the probability of plasma membrane (PM) wound repair following micropuncture. Large thin type I (ATI) alveolar epithelial cells were incubated for 10 min in hypotonic (240 mosM), isotonic (290 mosM), or hypertonic (340 mosM) media and wounded with a 1-μm-diameter glass pipette, and their subsequent PM wound repair response was characterized on the basis of cytosolic calcein fluorescence decay patterns. Exposure to hypertonic media was associated with a significantly greater probability of successful PM repair (101 of 108 cells; 94 ± 2%) than exposure to either isotonic (92 of 112 cells; 82 ± 4%; P < 0.01) or hypotonic media (85 of 112 cells; 76 ± 4%; P < 0.003).

Molecular Specificity of Endocytic Pathways in ATI

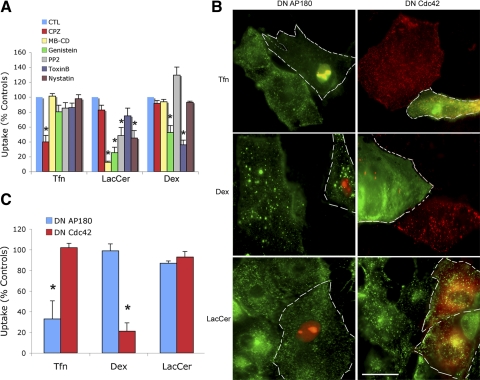

Pathway selectivity of pharmacological inhibitors.

BODIPY-LacCer uptake was inhibited by the cholesterol sequestering agent mβ-CD as well as by nystatin, by the nonspecific tyrosine kinase inhibitor genistein, and by the Src kinase inhibitor PP2 (Fig. 2A). However, BODIPY-LacCer uptake was unaffected by pharmacological inhibitors of the clathrin pathway such as CPZ or inhibitors of the fluid-phase pathway such as toxin B. As expected, the uptake of Tfn was inhibited by CPZ but was unaffected by inhibitors of caveolar endocytosis (mβ-CD and PP2) or of fluid-phase uptake such as toxin B. In turn, Dex uptake was inhibited by toxin B but not by PP2, mβ-CD, nor CPZ. In aggregate, manipulating key elements of the three endocytosis pathways under consideration by molecular and pharmacological means established Tfn, Dex, and LacCer as pathway-specific cargo.

Fig. 2.

A: effects of 6 pharmacological agents on the endocytic uptake of transferrin (Tfn), lactosyl ceramide (LacCer), and dextran (Dex) in rat ATI. Data are the results of pulse-chase experiments at the 5 min time point. CTL, placebo control; CPZ, chlorpromazine; MB-CD, methyl β-cyclodextrin; PP2, 4-amino-5-(4-chlorophenyl)-7-(t-butyl)pyrazolo[3,4-d]pyramidine. *P < 0.01 compared with controls. B: effects of dominant-negative (DN) AP180 and Cdc42 gene overexpression on endocytic uptake of Tfn, Dex, and LacCer in rat ATI. The cells in left panels were cotransfected with DN AP180 and pDsRed2-Nuc, so that the nuclei of transfected cells (also marked by white dashed margins) could be identified by their red color. In contrast, the endocytic cargo molecules (AF488-Tfn, AF488-Dex, and BODIPY-LacCer) appear green. To evaluate the effects of DN Cdc42 overexpression on Tfn and Dex uptake the cells in the top 2 right panels were transfected with DN-Cdc42-GFP. They may be identified by their green cytoplasmic fluorescence (outlined by white broken lines). The cargo molecules (AF594-Tfn and AF594-Dex) appear in red. Because BODIPY-LacCer emits a green fluorescence, the cells at bottom right were transfected with DN Cdc42-mRed, i.e., transfected cells (outlined by white broken lines) may be identified by their red fluorescence. Note that overexpression of DN AP180 resulted in selective inhibition of Tfn uptake (top left) whereas overexpression of DN Cdc42 resulted in selective inhibition of Dex uptake (middle right). Scale bar, 50 μM. C: averages ± SD of results from experiments shown in B (derived from ≥8 cells in each of 3 separate isolations/experiments). *P < 0.01 compared with controls.

Overexpression of dominant-negative constructs acting on clathrin and fluid-phase pathways.

The overexpression of the dominant-negative construct DN AP180, an adaptor protein and key mediator of clathrin-dependent endocytosis, inhibited 68% of Tfn uptake but had no effect on Dex uptake (Fig. 2, B and C). Overexpression of the dominant-negative construct DN Cdc42, a cytoskeleton-associated protein and key regulator of fluid-phase endocytosis, inhibited 80% of Dex uptake but had no effect on the internalization of Tfn (Fig. 2, B and C). Not surprising, these data confirm that Tfn and Dex may be used to quantitate clathrin and fluid-phase uptake mechanisms in ATI. Neither DN AP180 nor DN Cdc42 altered the uptake of BODIPY-LacCer, suggesting that this sphingolipid is internalized by an alternative endocytic pathway.

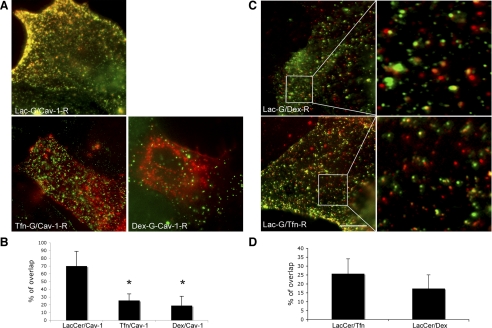

Overexpression of Cav-1 constructs and LacCer itinerary.

As shown in Fig. 3, A and B, 70% of internalized BODIPY-LacCer colocalized with mRed-Cav-1, whereas only 20% of internalized Dex and 25% of internalized Tfn colocalized with mRed Cav-1. BODIPY-LacCer colocalized only 25 and 20% with the clathrin and fluid-phase markers AF647-Tfn and AF647-Dex, respectively (Fig. 3, C and D). These findings suggest that caveolar endocytosis is the preferred uptake route for the sphingolipid LacCer (31).

Fig. 3.

Relative distributions (colocalization) of caveolin-1 (Cav-1) with LacCer, Tfn, and Dex in mRed-tagged Cav-1 overexpressing ATI. A and B: there is a 70% concordance between the itineraries of LacCer (G, green) and Cav-1 (R, red), but only a 20 and 25% colocalization between Dex and Tfn, respectively. *P < 0.01 compared with LacCer/Cav-1. C and D: colocalization studies between LacCer-G (BODIPY-green)/Dex-R (AF647-far red) and LacCer-G (BODIPY-green)/Tfn-R (AF647-far red), with corresponding magnification of a small region. The lack of significant colocalization (red and green labels remain for the most part confined to different membrane compartments) is consistent with Dex and Tfn's preference for different, i.e., noncaveolar uptake routes. Scale bar, 20 μM.

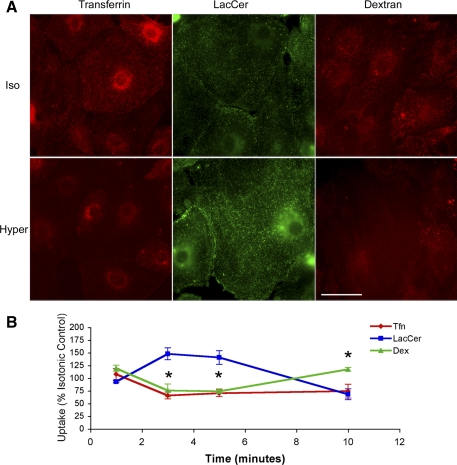

Endocytic PM Remodeling in Response to Hypertonic Stress

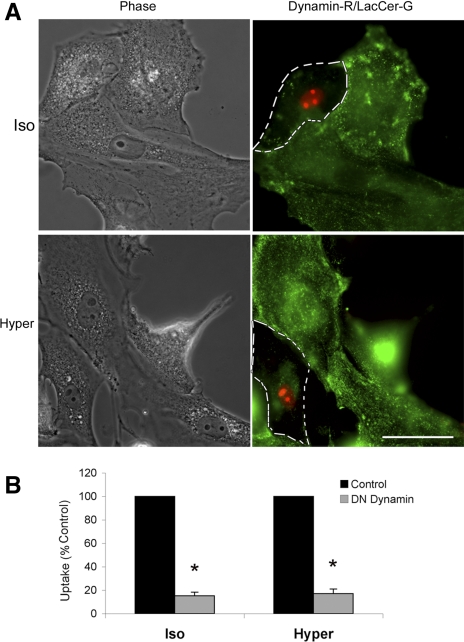

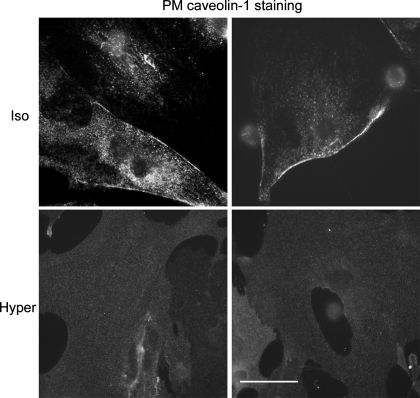

The relatively small increase in medium tonicity (50 mosM) caused divergent PM retrieval responses, enhancing caveolar endocytosis on the one hand and inhibiting clathrin-dependent and fluid-phase endocytosis on the other (Fig. 4). ATI transfected with a dominant-negative construct of dynamin failed to internalize LacCer under either control or osmotic stress conditions (Fig. 5). This observation indicates that the hypertonic stress-induced increase in LacCer uptake was indeed-mediated by caveolar uptake mechanisms as opposed to a PM translocase. Consistent with this interpretation, immunostaining of antibodies with high affinity to the PM-associated Cav-1 indicated its translocation to a cytosolic compartment (Fig. 6).

Fig. 4.

Pulse-chase experiments of Tfn, LacCer, and Dex in ATI exposed to a 50 mosM increase in extracellular tonicity for 10 min. A: representative 5 min snap shots of Tfn (red)-, LacCer (green)-, and Dex (red)-labeled ATI after exposure to an isotonic (Iso; top) vs. hypertonic (Hyper, bottom) environment. Note that, compared with isotonic controls cells exposed to a hypertonic challenge lack the punctate Tfn and Dex structures, indicative of an endosomal staining pattern. In contrast, osmotically challenged cells show a more intense granular LacCer staining pattern consistent with enhanced endocytosis of this caveolar uptake label. Scale bar, 50 μM. B: average results of osmotic challenge responses shown as % of time-matched isotonic controls. Exposure of ATI to a 50 mosM increase in medium tonicity was associated with a transient inhibition of clathrin and fluid-phase marker uptake (Tfn and Dex) and an increase in caveolar endocytosis (LacCer). *P < 0.01 between LacCer and either Dex or Tfn at the 3-, 5-, and 10-min time points.

Fig. 5.

Internalization of LacCer (green) in normal ATI and ATI, which overexpress a DN dynamin construct (red nuclear label). ATI were cotransfected with DN dynamin and pDsRed2-Nuc to overexpress a dominant-negative dynamin construct. DN dynamin-expressing cells were outlined by dashed lines and compared with the neighboring untransfected cells in the same image field. A representative example (A) and summary statistics (B) indicate an 80% reduction of LacCer uptake in DN dynamin transfected cells. Scale bar, 50 μM. *P < 0.01 compared with control.

Fig. 6.

Representative ATI cell images indicating the abundance of PM-associated Cav-1 (labeled with an antibody with particular affinity to PM-associated Cav-1) in ATI under isotonic conditions (top; note the intense fluorescence at the cell border). Contrast the paucity/absence of PM-associated Cav-1 in cells 5 min after a hypertonic challenge (note the absence of fluorescence at the cell border). Scale bar, 50 μM.

Tonicity-Induced Stimulation of Caveolar Endocytosis and Enhanced PM Wound Repair are Dependent on Src Pathway Activation

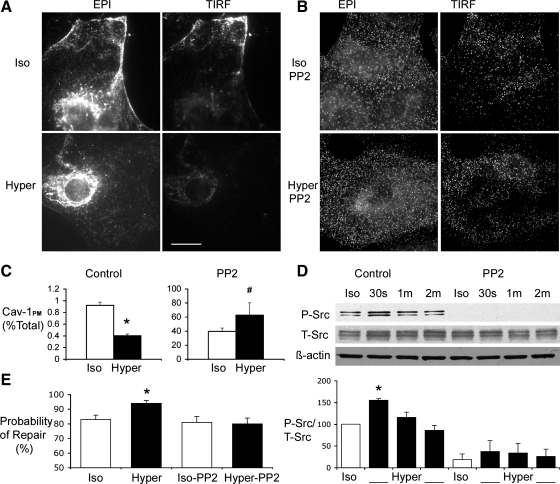

Consistent with the interpretation of Fig. 6, the epifluorescence and TIRF images of Fig. 7A show that a 50 mosM increase in medium tonicity caused the internalization of PM associated Cav-1 (note the decrease in PM fluorescence in both epifluorescence and TIRF images labeled Hyper in Fig. 7A). Cav-1 internalization was blocked by pretreatment of ATI with the Src-kinase inhibitor PP2 (Fig. 7, B and C). This observation is in agreement with the PP2-related inhibition of Lac-Cer uptake shown in Fig. 2A. By preventing the osmotic stress-induced activation of the Src pathway (Fig. 7D), PP2 not only inhibited caveolar endocytosis but also abolished the salutary effect of hypertonic exposure on PM wound repair (Fig. 7E).

Fig. 7.

Effects of Src-kinase inhibition on osmotic stress induced caveolar endocytosis and cell repair. A: representative epifluorescence (EPI, left) and total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF, right) images of ATI labeled with a Cav-1 antibody. Note the intense peripheral (PM-associated) Cav-1 fluorescence in cells exposed to isotonic media (top). Note the decrease in PM fluorescence in images labeled Hyper. Scale bar, 20 μM. B: PP2 pretreatment significantly blocked the translocation of Cav-1 from PM. Note the similarity in fluorescence patterns and intensity between Iso-PP2 and Hyper-PP2. C: summary results of the effects of hypertonic exposure on the distribution of fluorescence between PM and cytosol. The fluorescence intensity of TIRF images (PM-associated Cav-1, Cav-1PM) was normalized by the Cav-1 fluorescence intensity of EPI images (total Cav-1 pool). Note that exposing ATI to PP2 under isotonic conditions substantially increased the PM fraction Cav-1 and that a hypertonic challenge increased that fraction further. *P < 0.01, #P < 0.05. D: phosphorylated Src and total Src were identified as 59-kDa protein by Western immunoblotting analysis, hypertonic exposure caused a statistically significant phosphorylation of Src at the 30-s time point (P < 0.01 compared with isotonic control), which was blocked in the presence of PP2. E: effects of hypertonic challenge on the probability of PM wound repair in the presence and absence of PP2. Note that pretreatment of PP2 abolished the tonicity-induced increase in the probability of PM wound repair following micropuncture. *P < 0.01 compared with isotonic control.

DISCUSSION

We have shown that a relatively small increase in extracellular tonicity of 50 mosM inhibits PM retrieval in ATI via the receptor-mediated and fluid-phase endocytic pathways. Our observations also suggest that this inhibition is cargo and uptake pathway specific and does not apply to caveolar endocytosis, which in fact was transiently enhanced. We have shown that ATI exposed to hypertonic media are more likely to repair PM wounds and that tonicity-mediated facilitation of cell repair is critically dependent on Src pathway activation and associated caveolar endocytosis.

Our interest in the topic “osmotic stress response of ATI” originated with the observation that exposing rodent lungs to a hypertonic environment resulted in alveolar epithelial cell protection against deformation injury (25). We had initially postulated that this mechanoprotective effect reflected hypertonic stress-induced increases in the cells' surface-to-volume ratio. A disproportionate decrease in cell volume relative to the surface area of the PM envelope would allow excess PM to unfold and thereby maintain sublytic tension in the face of deforming stress. Given this hypothesis we needed to understand the mechanisms/molecular pathways by which ATI regulate PM surface area in response to environmental stress (21, 22). In reviewing the large literature on the topic it became readily apparent that osmotic stress responses as well as the cargo selectivity of endocytic pathways varied greatly among cell types (9, 12, 18). Furthermore, most studies to date had employed much larger stresses (hundreds of mosM) than were tested here. Since no ATI-specific data were available, we felt it important to validate the tools and approaches that are commonly used to characterize endocytic uptake pathways in other mammalian systems. Consequently, Tfn, Dex, and LacCer proved to be pathway-specific cargo of receptor-mediated, fluid-phase, and caveolar endocytosis mechanisms in ATI, respectively. The overexpression of the dominant-negative construct DN AP180, a key mediator of clathrin-dependent endocytosis, inhibited 68% of Tfn uptake, whereas overexpression of the dominant-negative construct DN Cdc42, a key regulator of fluid-phase endocytosis, inhibited 80% of Dex uptake (Fig. 2). Importantly, inhibition of these pathways did not shunt the respective cargo molecules to alternative uptake routes (16). The results of pharmacological inhibition of the clathrin, fluid-phase, and caveolar pathways, respectively, were consistent with responses in other mammalian cells (18). Accordingly, CPZ inhibited Tfn/receptor-mediated uptake, whereas toxin B was relatively selective for Dex/fluid-phase endocytosis. Moreover, cholesterol depletion of the PM with the sequestering agent mβ-CD was associated with a profound inhibition of LacCer uptake, presumably reflecting destruction of caveolar microdomains. In contrast to some mammalian cells, reducing the cholesterol content of the PM had no effect on Cdc42-dependent fluid-phase endocytosis mechanisms in ATI (2).

Acute exposure of ATI to a 50 mosM increase in medium tonicity caused a divergent cargo- and pathway-specific membrane internalization response. The uptake of clathrin- and fluid-phase-dependent endocytosis markers was inhibited, whereas that of LacCer, a glycosphingolipid and cargo with preference for the caveolar pathway, was enhanced. Selective inhibition of receptor-mediated endocytosis by hypertonic media had been first reported in polymorphonuclear leukocytes (3). This inhibition occurred irrespective of the ionic strength of the hypertonic solution but did not extend to the uptake of the fluid-phase marker Dex. Inhibition of clathrin-mediated endocytosis was later confirmed in chick as well as human fibroblasts and was attributed to a cytoplasm acidification-mediated clathrin precipitation into microcages (11). Although cytosolic acidification consequent to hypertonic shock was associated with inhibition of Dex uptake in Dictyostelium cells (26), in mammalian cells hypertonic inhibition of fluid-phase endocytosis had not been reported before.

Previous observations on fibroblasts (NIH3T3) had suggested that a large hypertonic stress (600 mM sucrose) initiates a Src kinase-mediated phosphorylation and translocation of Cav-1 from the PM to the cytosol (15, 38). Our measurements of osmotic stress-induced changes in intracellular Cav-1 distributions in ATI and their dependence on Src pathway activation are consistent with such a mechanism (Figs. 6 and 7). Moreover, the enhanced LacCer uptake following the hypertonic challenge suggests a concomitant upregulation of caveolar endocytosis in ATI. The literature suggests that the activation and translocation of caveolar scaffolding proteins is a required, but not a sufficient, step in the endocytosis of caveolar cargo molecules (18). In fibroblasts, activated Cav-1 had been shown to translocate to focal adhesion complexes raising the possibility of a mechanotransduction mechanism (38). Since Cav-1 translocation could be enhanced by actin network-disrupting agents, it was proposed that Cav-1 activation and translocation are nonspecific manifestation of actin network disruptions in response to a variety of cell stressors. It is generally assumed that the depolymerization of the subcortical cytoskeleton facilitates membrane trafficking to and from the PM. Accordingly, interventions favoring G actin over F actin formation also enhance exocytic responses such as surfactant secretion in type II cells (30).

The hypothesis that the enhanced Cav-1 translocation that had been observed in fibroblasts reflected a stress-related disruption of the actin network is at odds with an overwhelming body of evidence that hypertonic stress causes the accumulation of F actin and a concomitant polymerization of the subcortical actin network (12, 35). Notwithstanding cell-specific variability in the enzymes that influence both spatial and temporal control of cytoskeletal remodeling, molecular crowding, and reduced availability of free water have profound effects on nucleotide-dependent filament stability, lowering the critical concentration of ADP actin for assembly (5). It is therefore more appropriate to think in terms of osmotic stress-related actin remodeling as opposed to disruption. The uncritical acceptance of a binary state, in which the actin network either facilitates or inhibits membrane trafficking, would also be hard to reconcile with pathway- and cargo-specific effects of osmotic stress, i.e., enhancing some while inhibiting others. A spatially regulated reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton (CSK) can certainly propel vesicular membranes to target sites even without the involvement of conventional molecular motors (14, 28).

Having placed our endocytic PM remodeling results of ATI in the context of published data from nonpulmonary cells and tissues, we will now consider hypotheses that link osmotic stress-mediated PM remodeling with PM wound repair. Initial research on the determinants of PM wound repair underscored the importance of exocytic transport of calcium-sensitive endomembranes, notably of lysosomes, as prerequisite for successful lipid bilayer resealing (19, 33). It has only become clear recently that the accumulation of lysosome-derived lipids and acid sphingomyelinase at the wound site also triggers an endocytic response, without which bilayer repair is retarded or inhibited (34). The consequences of this series of trafficking events on PM biophysical properties have yet to be fully characterized and understood. On the basis of a detailed account of the temporal and spatial coordination between cytoskeletal remodeling and the accumulation of endomembrane-derived lipids at the injury site, Godin et al. (6) recently concluded that wound edge energy and the fluidity of the subcortical cytoskeleton and of the lipid bilayer were critical for successful repair of PM lesions. However, in the absence of compensatory mechanisms exposure to a hypertonic stress is expected to solidify, i.e., decrease the fluidity of either structure (42). The selective enhancement of caveolar endocytosis and the consequent removal of liquid-ordered PM domains may be one such compensatory mechanism. The osmotic stress-triggered synthesis of ectoins, zwitterionic water-binding organic molecules that have been shown to hydrate model membranes, may be another (10). Godin et al. demonstrated that wounding fluidizes the actin CSK near micropuncture sites irrespective of the actin polymerization state prior to wounding. To the extent to which CSK fluidity is a determinant of the adhesive interactions between PM lipids and the subcortical CSK (23), a fluid CSK network allows greater lateral mobility of PM lipids and thereby promotes bilayer defect closure.

In conclusion, we have shown that the membrane-retrieval response of primary rat ATI to a modest hypertonic stress is nuanced. It is associated with a transient inhibition of cargo uptake via the clathrin and fluid-phase pathways, whereas caveolar endocytosis appears to be enhanced. Activation of the Src pathway appears to be critical for this PM remodeling response. Our study was primarily motivated by interest in cell repair and by a search for lung-protective adjuncts in the care of mechanically ventilated patients. However, the endocytosis pathway-specific osmotic stress response of ATI, which are rich in caveolae, also suggests a means to enhance pulmonary drug or gene delivery through the use of hypertonic aerosols (8). Finally, the surprising finding that a hypertonic milieu enhances as opposed to retards alveolar epithelial repair, raises a number of testable mechanistic hypotheses about the biophysical determinants of cell repair and will further motivate efficacy studies in preclinical lung injury models.

GRANTS

This work was supported by grants HL 63178 to R. D. Hubmayr, GM 22942 and GM 60934 to R. E. Pagano, and the Mayo Foundation.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

Supplementary Material

REFERENCES

- 1. Belete HA, Godin LM, Stroetz RW, Hubmayr RD. Experimental models to study cell wounding and repair. Cell Physiol Biochem 25: 71–80, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cheng ZJ, Singh RD, Sharma DK, Holicky EL, Hanada K, Marks DL, Pagano RE. Distinct mechanisms of clathrin-independent endocytosis have unique sphingolipid requirements. Mol Biol Cell 17: 3197–3210, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Daukas G, Zigmond SH. Inhibition of receptor-mediated but not fluid-phase endocytosis in polymorphonuclear leukocytes. J Cell Biol 101: 1673–1679, 1985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dreyfuss D, Basset G, Soler P, Saumon G. Intermittent positive-pressure hyperventilation with high inflation pressures produces pulmonary microvascular injury in rats. Am Rev Respir Dis 132: 880–884, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Frederick KB, Sept D, De La Cruz EM. Effects of solution crowding on actin polymerization reveal the energetic basis for nucleotide-dependent filament stability. J Mol Biol 378: 540–550, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Godin LM, Vergen J, Prakash YS, Pagano RE, Hubmayr RD. Spatiotemporal dynamics of actin remodeling and endomembrane trafficking in alveolar epithelial type I cell wound healing. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. doi:10.1152/ajplung.00265.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Grembowicz KP, Sprague D, McNeil PL. Temporary disruption of the plasma membrane is required for c-fos expression in response to mechanical stress. Mol Biol Cell 10: 1247–1257, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gumbleton M, Hollins AJ, Omidi Y, Campbell L, Taylor G. Targeting caveolae for vesicular drug transport. J Control Release 87: 139–151, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hansen CG, Nichols BJ. Molecular mechanisms of clathrin-independent endocytosis. J Cell Sci 122: 1713–1721, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Harishchandra RK, Wulff S, Lentzen G, Neuhaus T, Galla HJ. The effect of compatible solute ectoines on the structural organization of lipid monolayer and bilayer membranes. Biophys Chem 150: 37–46, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Heuser J. Effects of cytoplasmic acidification on clathrin lattice morphology. J Cell Biol 108: 401–411, 1989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hoffmann EK, Lambert IH, Pedersen SF. Physiology of cell volume regulation in vertebrates. Physiol Rev 89: 193–277, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Idone V, Tam C, Andrews NW. Two-way traffic on the road to plasma membrane repair. Trends Cell Biol 18: 552–559, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kaksonen M, Toret CP, Drubin DG. Harnessing actin dynamics for clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 7: 404–414, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kang YS, Ko YG, Seo JS. Caveolin internalization by heat shock or hyperosmotic shock. Exp Cell Res 255: 221–228, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kumari S, Mayor S. ARF1 is directly involved in dynamin-independent endocytosis. Nat Cell Biol 10: 30–41, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Martin OC, Pagano RE. Internalization and sorting of a fluorescent analogue of glucosylceramide to the Golgi apparatus of human skin fibroblasts: utilization of endocytic and nonendocytic transport mechanisms. J Cell Biol 125: 769–781, 1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mayor S, Pagano RE. Pathways of clathrin-independent endocytosis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 8: 603–612, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. McNeil PL, Miyake K, Vogel SS. The endomembrane requirement for cell surface repair. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 4592–4597, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. McNeil PL, Steinhardt RA. Plasma membrane disruption: repair, prevention, adaptation. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 19: 697–731, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Morris CE. How did cells get their size? Anat Rec 268: 239–251, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Morris CE, Homann U. Cell surface area regulation and membrane tension. J Membr Biol 179: 79–102, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Oeckler RABW, Stroetz RW, Hubmayr RD. Osmotic pressure alters alveolar epithelial cell plasma membrane mechanics via P.IP2 and cytoskeletal rearrangement. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 179: A2499, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 24. Oeckler RA, Hubmayr RD. Cell wounding and repair in ventilator injured lungs. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 163: 44–53, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Oeckler RA, Lee WY, Park MG, Kofler O, Rasmussen DL, Lee HB, Belete H, Walters BJ, Stroetz RW, Hubmayr RD. Determinants of plasma membrane wounding by deforming stress. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 299: L826–L833, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Pintsch T, Satre M, Klein G, Martin JB, Schuster SC. Cytosolic acidification as a signal mediating hyperosmotic stress responses in Dictyostelium discoideum. BMC Cell Biol 2: 9, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Pol A, Martin S, Fernandez MA, Ingelmo-Torres M, Ferguson C, Enrich C, Parton RG. Cholesterol and fatty acids regulate dynamic caveolin trafficking through the Golgi complex and between the cell surface and lipid bodies. Mol Biol Cell 16: 2091–2105, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pollack GH, Reitz FB. Phase transitions and molecular motion in the cell. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand) 47: 885–900, 2001 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Puri V, Watanabe R, Singh RD, Dominguez M, Brown JC, Wheatley CL, Marks DL, Pagano RE. Clathrin-dependent and -independent internalization of plasma membrane sphingolipids initiates two Golgi targeting pathways. J Cell Biol 154: 535–547, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rose F, Kurth-Landwehr C, Sibelius U, Reuner KH, Aktories K, Seeger W, Grimminger F. Role of actin depolymerization in the surfactant secretory response of alveolar epithelial type II cells. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 159: 206–212, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sharma DK, Brown JC, Choudhury A, Peterson TE, Holicky E, Marks DL, Simari R, Parton RG, Pagano RE. Selective stimulation of caveolar endocytosis by glycosphingolipids and cholesterol. Mol Biol Cell 15: 3114–3122, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Singh RD, Liu Y, Wheatley CL, Holicky EL, Makino A, Marks DL, Kobayashi T, Subramaniam G, Bittman R, Pagano RE. Caveolar endocytosis and microdomain association of a glycosphingolipid analog is dependent on its sphingosine stereochemistry. J Biol Chem 281: 30660–30668, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Steinhardt RA, Bi G, Alderton JM. Cell membrane resealing by a vesicular mechanism similar to neurotransmitter release. Science 263: 390–393, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Tam C, Idone V, Devlin C, Fernandes MC, Flannery A, He X, Schuchman E, Tabas I, Andrews NW. Exocytosis of acid sphingomyelinase by wounded cells promotes endocytosis and plasma membrane repair. J Cell Biol 189: 1027–1038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Thirone AC, Speight P, Zulys M, Rotstein OD, Szaszi K, Pedersen SF, Kapus A. Hyperosmotic stress induces Rho/Rho kinase/LIM kinase-mediated cofilin phosphorylation in tubular cells: key role in the osmotically triggered F-actin response. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 296: C463–C475, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Thorpe WP, Toner M, Ezzell RM, Tompkins RG, Yarmush ML. Dynamics of photoinduced cell plasma membrane injury. Biophys J 68: 2198–2206, 1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Vlahakis NE, Hubmayr RD. Cellular stress failure in ventilator-injured lungs. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 171: 1328–1342, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Volonte D, Galbiati F, Pestell RG, Lisanti MP. Cellular stress induces the tyrosine phosphorylation of caveolin-1 (Tyr(14)) via activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase and c-Src kinase. Evidence for caveolae, the actin cytoskeleton, and focal adhesions as mechanical sensors of osmotic stress. J Biol Chem 276: 8094–8103, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wang S, Hubmayr RD. Type I alveolar epithelial phenotype in primary culture. Am J Respir Crit Cell Mol Biol. [EPub ahead of print.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ware LB, Matthay MA. The acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 342: 1334–1349, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Weibel ER. The mystery of “non-nucleated plates” in the alveolar epithelium of the lung explained. Acta Anat (Basel) 78: 425–443, 1971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Zhou EH, Trepat X, Park CY, Lenormand G, Oliver MN, Mijailovich SM, Hardin C, Weitz DA, Butler JP, Fredberg JJ. Universal behavior of the osmotically compressed cell and its analogy to the colloidal glass transition. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 10632–10637, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.