Abstract

Estrogen receptors (ERs) are expressed in adipose tissue and skeletal muscle, with potential implications for glucose metabolism and insulin signaling. Previous studies examining the role of ERs in glucose metabolism have primarily used knockout mouse models of ERα and ERβ, and it is unknown whether ER expression is altered in response to an obesity-inducing high-fat diet (HFD). The purpose of the current study was to determine whether modulation of glucose metabolism in response to a HFD in intact and ovariectomized (OVX) female rats is associated with alterations in ER expression. Our results demonstrate that a 6-wk HFD (60% calories from fat) in female rats induces whole body glucose intolerance with tissue-specific effects isolated to the adipose tissue, and no observed differences in insulin-stimulated glucose uptake, GLUT4, or ERα protein expression levels in skeletal muscle. In chow-fed rats, OVX resulted in decreased ERα with a trend toward decreased GLUT4 expression in adipose tissue. Sham-treated and OVX rats fed a HFD demonstrated a decrease in ERα and GLUT4 in adipose tissue. The HFD also increased activation of stress kinases (c-jun NH2-terminal kinase and inhibitor of κB kinase β) in the sham-treated rats and decreased expression of the protective heat shock protein 72 (HSP72) in both sham-treated and OVX rats. Our findings suggest that decreased glucose metabolism and increased inflammation in adipose tissue with a HFD in female rats could stem from a significant decrease in ERα expression.

Keywords: glucose uptake, estrogen, diabetes, ovariectomy

type 2 diabetes, one of the main causes of mortality and morbidity worldwide (40), is characterized by insulin resistance, glucose intolerance, and inflammation and is closely associated with obesity. Clinical evidence suggests postmenopausal women have an increased risk of glucose intolerance and weight gain and that this is accompanied by increased inflammation and decreased insulin sensitivity (7, 33, 42). Estrogen replacement therapy in postmenopausal women ameliorates the increased risk of type 2 diabetes (2, 25, 28), even in the presence of increased abdominal fat (14). While this beneficial effect of estrogen is evident, the molecular mechanisms of estrogen and its active metabolite, 17β-estradiol (E2), in metabolic tissue remain unknown.

Estrogen exerts its effects through two nuclear receptors, estrogen receptor (ER)α and ERβ (11). ERα and ERβ are expressed in adipose tissue and skeletal muscle, with potential implications for glucose metabolism and insulin signaling. Previous studies demonstrate that ERα knockout mice are obese, insulin resistant, and exhibit glucose intolerance (5, 20). A recent study by Ribas et al. (37) further showed that ERα expression is critical for the maintenance of whole body insulin action and protection against tissue inflammation in response to high-fat feeding. These investigators suggest that ERα could play an important role in modulating inflammatory stress kinase proteins such as c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase (JNK) (37), known to interfere with insulin signaling (9, 16, 17, 37). Despite this important new information, the role of ERs in the pathogenesis of insulin resistance and glucose intolerance is not clear. Previous studies examining the role of ERs in glucose metabolism have primarily used knockout mouse models of ERα and ERβ and it is unknown whether ER expression is altered in response to an obesity-inducing high-fat diet (HFD). As a result, the impact of a HFD on ER expression in adipose tissue and skeletal muscle, and thus the role of ERs in mediating the metabolic actions of estrogen, remains a fundamental question. Therefore, the purpose of the present study was to determine whether modulation of glucose metabolism in response to a HFD in intact and ovariectomized (OVX) female rats is associated with alterations in ER expression.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

GLUT4 antibody (ab654) was purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, MA), ERα (MC-20) was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA), ERβ (PA1-310B) was purchased from Affinity BioReagents (Rockford, IL), and HSP72 was purchased from Stressgen (Victoria, BC, Canada). Phospho-SAPK/JNK (T183/Y185), total SAPK/JNK, and IκBα were purchased from Cell Signaling (Beverly, MA). Goat anti-mouse HRP-conjugated secondary antibody was obtained from Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA) and donkey anti-rabbit HRP-conjugated secondary antibody was purchased from Jackson (West Grove, PA). Enhanced chemiluminescence reagents were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA). [14C]mannitol and 2-deoxy-[1,2-3H]glucose were purchased from American Radiolabeled Chemicals (St. Louis, MO). All other reagents were obtained from Sigma.

Experimental animals and treatment.

Female Sprague Dawley rats (5 mo old) were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA) and singly housed in a temperature-controlled (22 ± 2°C) room with 12:12-h light-dark cycles. Chow rats were fed ad libitum on a soy protein-free diet (Harlan Teklad 2020X, Madison, WI, 10% calories from fat), whereas HF rats received a modified Kraegen diet (43) of 60% calories from fat for 6 wk as previously used (16), which contains the following: 254 g/kg casein, 85 g/kg sucrose, 169 g/kg cornstarch, 11.7 g/kg vitamin mix, 1.3 g/kg choline chloride, 67 g/kg mineral mix, 51 g/kg bran, 3 g/kg methionine, 19 g/kg gelatin, 121 g/kg corn oil, 218 g/kg lard. A preset amount of food (in excess of what was needed) was administered to each animal. The remaining food was weighed 2–3 days later, before giving a new batch of food. At the start of the diet, animals underwent ovariectomy (OVX) or sham surgery under ketamine-atropine-xylazine anesthesia (60 mg/kg body wt ketamine, 0.4 mg/kg body wt atropine, 8 mg/kg body wt xylazine). Bilateral flank incisions were made under aseptic conditions. The ovaries were identified and either bilaterally removed via cauterization (OVX) or left intact (sham). Wounds were closed using sutures and wound clips. The following four groups were assessed (n= 5–6 rats/group): 1) chow sham; 2) chow OVX; 3) HF sham; and 4) HF OVX. All protocols were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Kansas Medical Center.

Intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test.

An intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test (IPGTT) was performed during week 6 of the diet regimen. Overnight-fasted rats were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of pentobarbital sodium (2.5 mg/100 g body wt) and given a glucose load of 2 g/kg body wt in 0.9% saline. Tail blood samples were measured with a glucometer (Accu-Check) at time points 0, 15, 30, 60, 90, and 120 min after glucose injection. Serum insulin was measured via an ELISA according to the manufacturer's instructions (Alpco Diagnostics, 80-INSRT-E01; Salem, NH).

Tissue dissection.

During week 7, overnight-fasted animals were anesthetized under ketamine-atropine-xylazine anesthesia (60 mg/kg body wt ketamine, 0.4 mg/kg body wt atropine, 8 mg/kg body wt xylazine). One soleus and one extensor digitorum longus (EDL) muscle was dissected from each animal, each split longitudinally into strips, and assessed for glucose transport. The remaining soleus and EDL muscle from each animal was frozen in liquid nitrogen for Western blot analysis. Gonadal fat was removed from the ovaries and uterine horns, weighed, and then frozen in liquid nitrogen. The uterus was also removed and weighed.

Measurement of glucose transport activity.

Glucose transport was measured in soleus and EDL muscle strips as previously described (17). Muscle strips recovered for 60 min in flasks containing 2 ml of Krebs-Henseleit bicarbonate buffer (KHB) with 8 mM glucose, 32 mM mannitol, and a gas phase of 95% O2-5% CO2. The flasks were placed in a shaking incubator maintained at 35°C. Following recovery, the muscles were rinsed for 30 min at 29°C in 2 ml of oxygenated KHB containing 40 mM mannitol, with or without insulin (2 mU/ml). After the rinse step, muscles were incubated for 20 min at 29°C in flasks containing 2 ml KHB with 4 mM 2-[1,2-3H]deoxyglucose (2-DG) (1.5 μCi/ml) and 36 mM [14C]mannitol (0.2 μCi/ml), with or without insulin (2 mU/ml), with a gas phase of 95% O2-5% CO2 in a shaking incubator. The muscles were then blotted dry, clamp frozen in liquid nitrogen, and processed as described previously (13, 45) for determination of intracellular 2-DG accumulation (3H dpm) and extracellular space (14C dpm) on a scintillation counter.

Serum estradiol measurement.

Blood samples were collected at the time animals were euthanized, and the samples were allowed to clot at room temperature for 30 min. Samples were spun at 17,500 g for 20 min at 4°C. Serum estradiol levels were measured by Estradiol E2 Coat-a-Count Assay (Siemens Diagnostics, TKE21).

Western blotting.

Muscles clamp frozen in liquid nitrogen were homogenized in a 12:1 (volume-to-weight) ratio of ice-cold buffer from Biosource (Invitrogen, Camarillo, CA) containing 10 mM Tris·HCl (pH 7.4); 100 mM NaCl; 1 mM each of EDTA, EGTA, NaF, and phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride; 2 mM Na3VO4; 20 mM Na4P2O7; 1% Triton X-100; 10% glycerol; 0.1% SDS; 0.5% deoxycholate; and 250 μl/5 ml protease inhibitor cocktail. Homogenized samples were rotated for 30 min at 4°C and then centrifuged for 20 min at 3,000 rpm at 4°C. The protein concentration of the supernatant was determined by the Bradford method (Bio-Rad). Samples were prepared in 5× Laemmli buffer containing 100 mM dithiothreitol and boiled in a water bath for 5 min. Samples analyzed for GLUT4 protein were not boiled. Protein (30–75 μg) was separated on a SDS-PAGE (8.75–10%) gel followed by a wet transfer to a nitrocellulose membrane for 60–90 min (200 mA). Total protein was visualized by Ponceau staining, and blots were normalized to the 45-kDa band as previously described (15). As the GLUT4 antibody only works with nondenatured protein, we chose to normalize all protein measurements to Ponceau staining, which does not require denaturing. Membranes were blocked for 1 h at room temperature in 5% nonfat dry milk in Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween 20 (TBST) and then incubated overnight with the appropriate primary antibodies. Antibodies were diluted in 1% nonfat dry milk in TBST or in 1% bovine serum albumin in TBST. Blots were incubated in a HRP-conjugated secondary antibody in 1% nonfat dry milk in TBST for 1 h at room temperature and visualized by ECL. Bands were quantified using ImageJ densitometry. To serve as a positive control for ERα, uterine tissue was initially used to detect and quantify expression of the full length 66-kDa protein.

Statistical analysis.

Results are presented as means ± SE. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05 and determined by one-way or two-way ANOVA and Student-Newman-Keuls post hoc test.

RESULTS

Effects of diet and OVX on food intake and body composition.

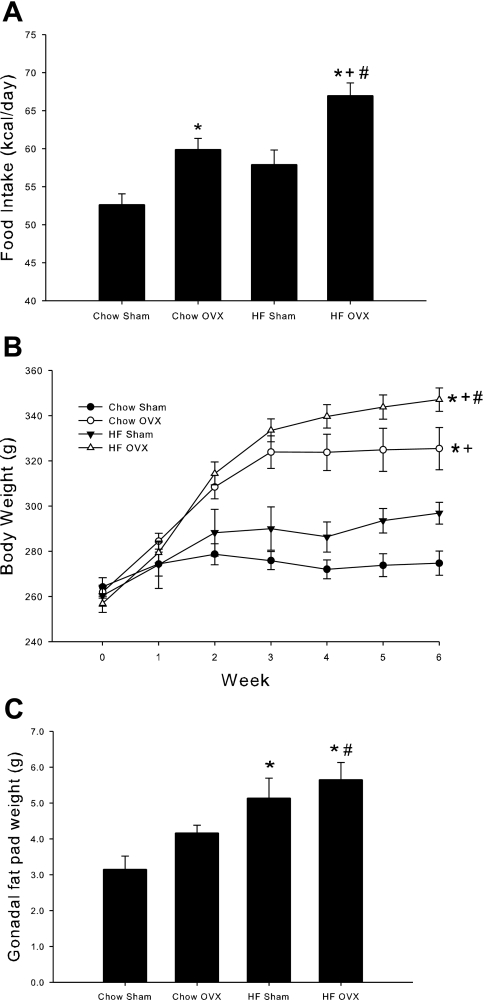

Uterine weight is a commonly used bioassay to assess in vivo estrogen status. In the current study, OVX rats had significantly lower uterine weight compared with sham-treated rats (0.415 ± 0.016 vs. 1.618 ± 0.108 mg/g body wt; P < 0.001), confirming negligible estrogen influence in OVX rats as a result of surgically removing the ovaries. To confirm the in vivo estrogen status, serum E2 levels were also measured. OVX significantly decreased serum E2 levels compared with sham-treated animals (7.6 ± 0.9 vs. 11.9 ± 1.8 pg/ml; P < 0.05), which is consistent with previous reports in the literature (18, 22). The 6-wk HFD did not significantly alter uterine weight or serum E2 levels in either OVX or sham-treated animals, consistent with previously reported data (1, 6). Over the course of the 6-wk diet regimen, female rats that underwent OVX demonstrated greater average daily food intake and increased body weight compared with sham-treated rats, with no significant difference in food intake or weight gain as a result of the HFD in sham-treated rats (Fig. 1, A and B). OVX animals fed a HFD demonstrated greater food intake and weight gain compared with all other groups. Both groups of HFD animals gained most of their weight in first 2–3 wk of high-fat feeding. However, the body weight of the animals that underwent OVX and were fed a HFD increased at a greater rate during this period. After week 3, the OVX animals fed the HFD continued to gradually increase their body weight, and the sham-treated animals fed the HFD remained fairly constant. Assessment of fat mass, as measured by gonadal fat pad weight, revealed a different pattern from that observed for food intake and body weight. Despite increased food intake and body weight as a result of OVX, no increase in gonadal fat was observed in this group (Fig. 1C). The HFD resulted in a significant increase in gonadal fat pad weight in both sham- and OVX-treated rats.

Fig. 1.

The combination of high-fat diet (HFD) and ovariectomy (OVX) increases food intake, body weight, and gonadal fat weight. Average daily food intake was measured over the course of a 6-wk chow or HFD (A). At the end of the 6-wk study, body weight (B) and gonadal fat weight (C) were measured. Values are means ± SE for 5–6 rats per group. *P < 0.05 vs. chow sham; +P < 0.05 vs. HF sham; #P < 0.05 vs. chow OVX.

Effects of diet and OVX on glucose tolerance.

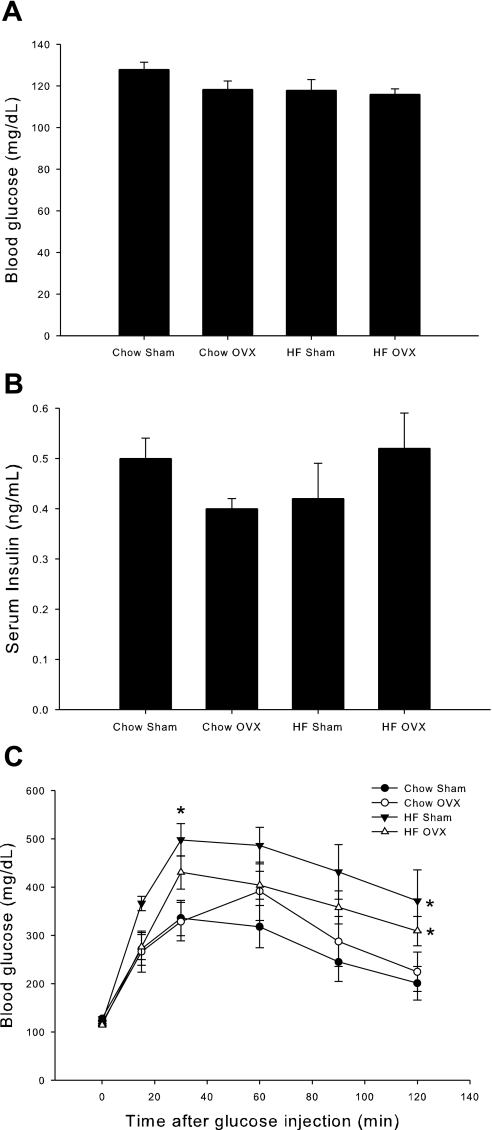

Fasting glucose and insulin levels did not differ across experimental groups at the end of the 6-wk diet (Fig. 2, A and B, respectively). An intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test (IPGTT) was performed to assess whole body glucose clearance in response to a glucose challenge. The HFD resulted in a decrease in whole body glucose tolerance, as demonstrated by the inability of HFD rats to effectively clear glucose from their blood by the end of the 2-h test, compared with rats fed a chow diet (Fig. 2C). While OVX rats fed a HFD had slightly lower glucose values throughout the test, these values were not significantly different from sham-treated animals fed a HFD. Similarly, OVX did not significantly alter glucose clearance in chow-fed rats compared with sham controls. Serum insulin levels during the IPGTT did not differ among the groups (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

A 6-wk HFD decreases glucose tolerance in female rats. At the end of the 6-wk diet, rats were fasted overnight, and fasting blood glucose (A) and fasting serum insulin (B) were measured. An intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test (IPGTT) was then performed (C). Rats were injected with a glucose load of 2 g/kg body wt ip. Blood glucose was measured at time 0 and 15, 30, 60, 90, and 120 min after injection using a glucometer. Values are means ± SE for 5–6 rats per group. Serum insulin values are means ± SE for 2–6 rats per group. *P < 0.05 vs. chow sham.

Effects of diet and OVX on insulin-stimulated skeletal muscle glucose uptake.

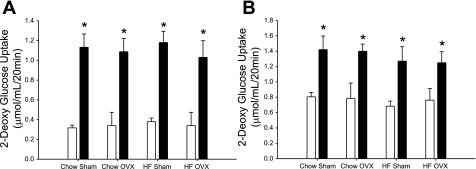

To investigate the effects of diet and OVX on skeletal muscle glucose uptake, we performed 2-DG uptake assays on the predominately slow-twitch soleus or the predominately fast-twitch extensor digitorum longus (EDL) muscles. Insulin-stimulated glucose uptake increased above basal in all groups examined (Fig. 3, A and B, respectively). However, no differences in basal- or insulin-stimulated skeletal muscle glucose uptake were observed across treatment groups in either the soleus or EDL muscles.

Fig. 3.

Insulin-stimulated skeletal muscle glucose transport was not altered by a HFD or OVX. Insulin-stimulated glucose transport was measured in soleus (A) and extensor digitorum longus (EDL) (B) muscles. Muscles were incubated in the absence of insulin (open bars) or in the presence of insulin (2 mU/ml, solid bars), along with 2-[1,2-3H]deoxyglucose and [14C]mannitol. Values are means ± SE for 5–6 rats per group. *P < 0.05, insulin vs. basal.

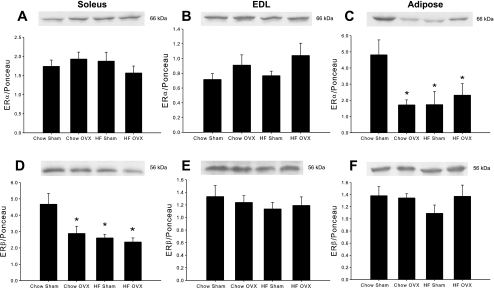

Effects of diet and OVX on ERα, ERβ, and GLUT4 protein levels.

The effects of high-fat feeding on ER protein expression in metabolic tissue have not been previously examined in nontransgenic animal models. ERα and ERβ are both prevalent in skeletal muscle and adipose tissue, with ERα expression shown to be more highly expressed than ERβ in insulin-sensitive tissue (37). Neither OVX nor the HFD had an effect on ERα expression in the soleus or EDL muscles (Fig. 4, A and B). However, ERα expression was significantly decreased in adipose tissue in response to OVX and the HFD (Fig. 4C). In OVX rats fed a HFD, the decrease in ERα was not greater than with either intervention alone. In contrast with ERα expression, there was an effect of OVX and diet on ERβ expression in skeletal muscle, but these effects were isolated to the soleus muscle. In this muscle, OVX and a HFD resulted in significant decreases in ERβ expression compared with sham controls (Fig. 4D). The combination of a HFD with OVX did not result in a greater decrease in ERβ expression in soleus muscle, and no changes with OVX or diet were observed in the EDL muscle (Fig. 4E). In the adipose tissue, ERβ expression was unchanged by OVX or a HFD (Fig. 4F).

Fig. 4.

HFD and OVX decrease ERα in adipose tissue and ERβ in soleus muscle. ERα (A–C) and ERβ (D–F) protein levels were measured in the soleus and EDL muscles and adipose tissue by Western blot analysis. Protein levels were normalized to total protein measured by Ponceau staining. Values are means ± SE for 5–6 samples per group. *P < 0.05 vs. chow sham.

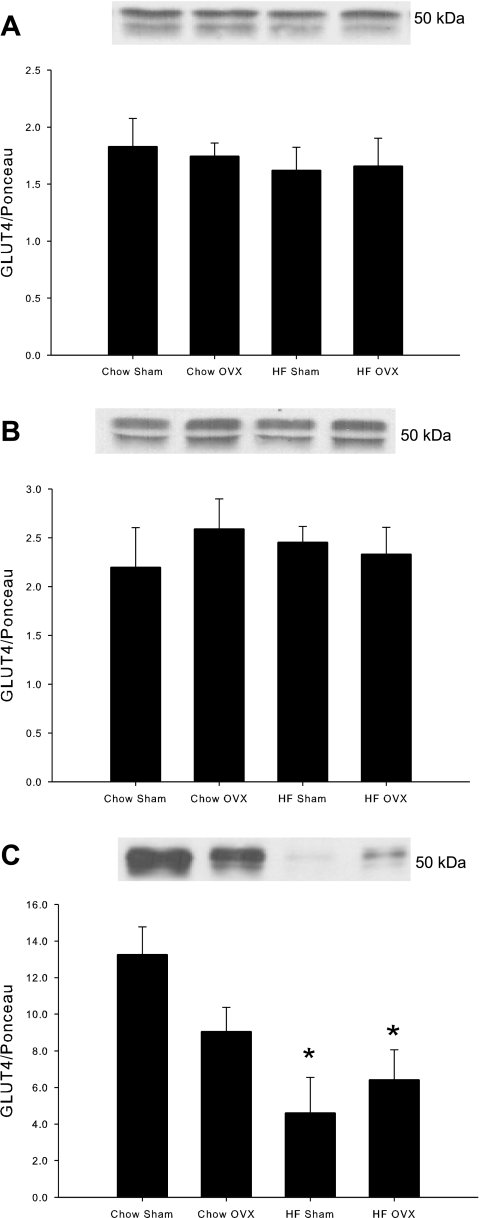

The effect of a HFD on GLUT4 protein expression is equivocal with some studies demonstrating a decrease or no change in GLUT4 protein expression as a result of high-fat feeding (19, 24, 26, 39, 41, 44, 47). In female rats subject to OVX or sham surgery, a 6-wk HFD had no effect on GLUT4 protein expression in either the soleus or EDL muscle (Fig. 5, A and B). However, the HFD dramatically reduced GLUT4 protein expression in adipose tissue in both sham- and OVX-treated rats (65% and 52%, respectively; Fig. 5C). OVX in chow-fed rats resulted in lower GLUT4 levels in adipose tissue compared with sham-treated chow rats, although these differences were not statistically significant (P = 0.07).

Fig. 5.

HFD and OVX decrease GLUT4 protein levels in adipose tissue. Protein levels were measured in soleus muscle (A), EDL muscle (B), and adipose tissue (C) by Western blot analysis. Protein levels were normalized to total protein measured by Ponceau staining. Values are means ± SE for 5–6 muscles per group. *P < 0.05 vs. chow sham.

Effects of diet and OVX on stress kinases and HSP72 protein levels.

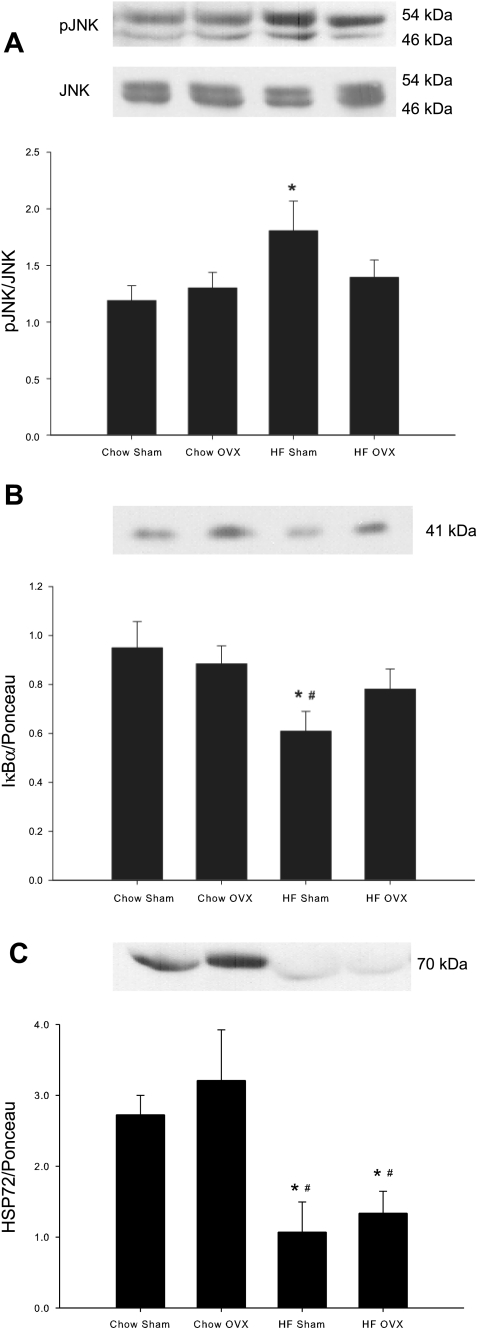

Activation of the stress kinases c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase (JNK) and inhibitor of κB kinase β (IKKβ) was assessed via Western blot analysis. JNK activation was assessed by measuring changes in JNK protein phosphorylation and IKKβ by protein levels of IκBα, the downstream protein targeted for degradation by IKKβ. JNK phosphorylation was increased as a result of the HFD in adipose tissue (Fig. 6A), but no change in JNK phosphorylation occurred in either soleus or EDL muscle in response to diet (data not shown). JNK phosphorylation with OVX treatment alone or in combination with a HFD was not different from that in chow-fed sham animals in adipose tissue or skeletal muscle. Activation of IKKβ was also increased with the HFD in adipose tissue, as indicated by decreased expression of IκBα (Fig. 6B). No changes in adipose tissue IκBα protein expression occurred with OVX in either chow or high fat-fed rats. In addition, no changes were observed in IκBα expression in either the soleus or EDL muscle as a result of diet or OVX (data not shown). Six weeks of a HFD dramatically decreased protein levels of heat shock protein 72 (HSP72) in the adipose tissue of both sham-treated and OVX rats (Fig. 6C). OVX alone had no effect on protein levels of HSP72 in adipose tissue. Neither the HFD nor OVX resulted in alterations in HSP72 protein expression in the soleus or EDL muscles (data not shown).

Fig. 6.

HFD increases stress kinase activation and decreases HSP72 expression in adipose tissue. Phosphorylated (p)-JNK/total JNK (A), IκBα (B), and HSP72 (C) protein levels were measured by Western blot analysis. Both the 46-kDa and 54-kDa bands were quantified for pJNK and JNK. Nonphosphorylated protein levels were normalized to total protein measured by Ponceau staining. Values are means ± SE for 5–6 samples per group. *P < 0.05 vs. chow sham; #P < 0.05 vs. chow OVX.

DISCUSSION

The purpose of the current study was to examine the effects of a HFD on adipose tissue and skeletal muscle glucose metabolism in female rats with and without OVX and to determine whether modulation of glucose metabolism in response to a HFD could be attributed to alterations in ER expression. While a short-term HFD in female rats induced whole body glucose intolerance, tissue-specific effects were isolated to the adipose tissue with no observed differences in insulin-stimulated glucose uptake, GLUT4, or ERα protein expression levels in skeletal muscle. GLUT4 protein decreased dramatically in adipose tissue of OVX and sham-treated rats as a result of a HFD, as did expression of ERα, the ER isoform previously shown to positively mediate glucose metabolism (3, 4, 29). Increased stress kinase activation and decreased HSP72 expression in adipose tissue in response to a HFD further demonstrates the impact of high-fat feeding on this tissue. These new findings highlight the differential effects of high-fat feeding in female compared with male rats, with previous studies demonstrating a significant decrease in skeletal muscle glucose metabolism in response to a HFD in male rats (16, 19, 32, 44, 47). In addition, our findings suggest a high-fat diet-induced loss of ERα in adipose tissue may be a contributing factor in the pathogenesis of glucose intolerance in female rats.

Ribas et al. (37) recently showed that female ERα knockout mice have decreased whole body glucose tolerance compared with wild-type mice, suggesting that the absence of ERα results in decreased glucose metabolism. While these data indicate that ERα is critical for the maintenance of whole body insulin action, the effect of a HFD on ER expression in insulin responsive tissue was unknown. Our findings reveal that ERα expression was decreased with a HFD only in the adipose tissue, which also displayed decreased GLUT4 protein and likely reflects lower glucose utilization in this tissue. OVX animals fed a chow diet demonstrated decreased ERα without corresponding changes in GLUT4, whole body glucose tolerance, or markers of inflammation. While the role of ERα in mediating glucose metabolism cannot be firmly established from these data, these findings suggest ERα-mediated effects may be dependent on additional changes induced by the HFD (stress kinase activation and HSP expression changes). In contrast, in the insulin-responsive skeletal muscle tissue, ERα expression was unchanged as was glucose uptake and GLUT4 protein expression levels. It is still possible that in insulin-resistant skeletal muscle (such as that from male rats fed a HFD), alterations in ERα expression could occur and contribute to changes in glucose metabolism. Other data support our findings of an adipose tissue-specific effect of the HFD in female rats. For example, Riant et al. (36) demonstrated that the combination of a HFD and OVX resulted in decreased glucose utilization in adipose tissue with no changes in soleus or EDL muscles in female mice (these investigators did not assess ER expression changes). Our findings of decreased ERα in adipose tissue in the current study support the idea that ERα is the primary functioning ER in adipose tissue (3). In turn, ERβ has been suggested as the primary functioning ER in skeletal muscle (3), which is coincident with our findings of decreased ERβ in the soleus muscle in response to a HFD. Decreased ERβ, the ER isoform suggested to have a suppressive role on GLUT4 expression (4), could result in protection from HFD-induced insulin resistance in skeletal muscle. The effects of estrogen on skeletal muscle likely depend on the balance between the two receptors, and future studies are needed to determine the regulatory roles of ERs in skeletal muscle.

Barros et al. (3, 4) have previously shown that ERs modulate GLUT4 expression in adipose tissue and skeletal muscle. Although the potential mechanism has yet to be demonstrated in skeletal muscle, ERα could modulate GLUT4 expression through specificity protein 1 and nuclear factor-κB. Ribas et al. did not find a decrease in skeletal muscle GLUT4 expression in ERα knockout mice despite insulin resistance and decreased glucose uptake in these mice (37). As these investigators point out, GLUT4 expression is regulated by redundant transcriptional pathways and ERα is likely only one of these pathways. However, our findings, and others (3) seem to suggest that ERα modulation of GLUT4 occurs primarily in the adipose tissue, and future studies will be needed to assess transcriptional control of GLUT4 by ERα in adipose tissue.

Estrogen has the potential to regulate fat storage and triacylglyceride accumulation by altering transcription of lipogenic proteins such as SREBP-1 and its downstream targets, ACC, and FAS (5, 8, 10, 23, 31). The effects of estrogen on lipogenic pathways have primarily been assessed in response to estrogen treatment or replacement. For example, Phrakonkham et al. (34) demonstrated that estrogen treatment increased FAS expression in cultured adipocytes. However, other studies have demonstrated opposite effects, with estrogen treatment in mice shown to decrease ACC and FAS mRNA in adipose tissue (6, 10). As has been previously shown, physiological estrogen levels may positively modulate glucose metabolism while high or low estrogen levels have a different effect (29, 30). More studies are needed to assess the role of estrogen and ER expression in modulating lipogenic pathways in cycling, OVX, and estrogen-treated animals.

Increased lipid intermediates and oxidative stress in insulin-responsive tissues can result in activation of stress kinases (16, 17, 21, 38, 46). We (16, 17) and others (9, 37) have previously shown that increased stress kinase activation and decreased HSP expression contribute to decreased insulin signaling and glucose uptake in skeletal muscle. Further evidence suggests that ERα may be involved in stress kinase activation and HSP expression. Ribas et al. demonstrate increased activation of JNK in skeletal muscle and adipose tissue of ERα knockout mice (37). When challenged with a HFD, ERα knockout mice display greater JNK activation and decreased HSP72 expression in adipose tissue compared with high-fat-fed wild-type mice (37). These data suggest that ERα may contribute to glucose regulation by positively modulating stress kinase activation and HSP expression. Evidence of inflammation, increased stress kinase activation (increased pJNK and decreased IκBα), and decreased HSP72 expression in adipose tissue were observed in the present study, although these changes did not always correlate with changes in ERα levels. With OVX alone, ERα protein was decreased in adipose tissue without changes in inflammation observed with a HFD (increased stress kinases and decreased HSP72). As OVX alone did not result in increased adiposity or glucose intolerance, it is possible the combination of decreased ERα and increased inflammation, as observed with the HFD, is critical for glucose intolerance. These results indicate the complex interplay of diet, hormones, and inflammation in insulin-responsive tissue require further investigation.

While this study focuses on the effect of a HFD and OVX on adipose tissue and skeletal muscle glucose metabolism, the liver is also an important regulator of glucose metabolism. In ERα knockout mice, modest hepatic insulin resistance is present as demonstrated by elevated hepatic glucose production during insulin stimulation and decreased insulin receptor substrate-PI 3-kinase p85 association compared with wild-type mice (37). Plausibly, ERα knockouts could have impaired signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) function. Estrogen treatment upregulates STAT3, which suppresses key enzymes in glucose homeostasis, including the gluconeogenic genes glucose-6-phosphatase (G6Pase) and phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PEPCK) (12, 27, 35). Future studies are needed to assess the effects of OVX and a HFD on ER protein expression in the liver and their role in regulating hepatocyte substrate metabolism.

While previous studies demonstrate the importance of the ERs in regulating glucose metabolism, the impact of a HFD on ER expression in skeletal muscle and adipose tissue was unknown. Findings from the present study indicate a short-term HFD in female rats induced whole body glucose intolerance, along with decreased ERα and GLUT4 in adipose tissue. In contrast with previous findings using male rodents, a short-term HFD did not decrease skeletal muscle glucose uptake in female rats. In addition, decreased ERβ expression was observed in the soleus muscle with no changes in skeletal muscle ERα expression. Future studies are needed to determine the tissue-specific regulation of ERs and how altered ER expression and/or function may contribute to increased susceptibility to type 2 diabetes.

GRANTS

The project described was supported by Grant AG-031575 and Grant P20-RR-016475 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health. We also acknowledge the Univ. of Kansas Medical Center Biomedical Research Training Program awarded to B. K. Gorres for financial support.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Jill Morris and Susan Smittkamp for technical assistance with this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1. Akamine EH, Marcal AC, Camporez JP, Hoshida MS, Caperuto LC, Bevilacqua E, Carvalho CR. Obesity induced by high-fat diet promotes insulin resistance in the ovary. J Endocrinol 206: 65–74, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Andersson B, Mattsson LA, Hahn L, Marin P, Lapidus L, Holm G, Bengtsson BA, Bjorntorp P. Estrogen replacement therapy decreases hyperandrogenicity and improves glucose homeostasis and plasma lipids in postmenopausal women with noninsulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 82: 638–643, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Barros RP, Gabbi C, Morani A, Warner M, Gustafsson JA. Participation of ERα and ERβ in glucose homeostasis in skeletal muscle and white adipose tissue. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 297: E124–E133, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Barros RP, Machado UF, Warner M, Gustafsson JA. Muscle GLUT4 regulation by estrogen receptors ERbeta and ERalpha. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 1605–1608, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bryzgalova G, Gao H, Ahren B, Zierath JR, Galuska D, Steiler TL, Dahlman-Wright K, Nilsson S, Gustafsson JA, Efendic S, Khan A. Evidence that oestrogen receptor-alpha plays an important role in the regulation of glucose homeostasis in mice: insulin sensitivity in the liver. Diabetologia 49: 588–597, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bryzgalova G, Lundholm L, Portwood N, Gustafsson JA, Khan A, Efendic S, Dahlman-Wright K. Mechanisms of antidiabetogenic and body weight-lowering effects of estrogen in high-fat diet-fed mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 295: E904–E912, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Carr MC. The emergence of the metabolic syndrome with menopause. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 88: 2404–2411, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chen X, Yu QQ, Zhu YH, Bi Y, Sun WP, Liang H, Cai MY, He XY, Weng JP. Insulin therapy stimulates lipid synthesis and improves endocrine functions of adipocytes in dietary obese C57BL/6 mice. Acta Pharmacol Sin 31: 341–346, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chung J, Nguyen AK, Henstridge DC, Holmes AG, Chan MH, Mesa JL, Lancaster GI, Southgate RJ, Bruce CR, Duffy SJ, Horvath I, Mestril R, Watt MJ, Hooper PL, Kingwell BA, Vigh L, Hevener A, Febbraio MA. HSP72 protects against obesity-induced insulin resistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 1739–1744, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. D'Eon TM, Souza SC, Aronovitz M, Obin MS, Fried SK, Greenberg AS. Estrogen regulation of adiposity and fuel partitioning. Evidence of genomic and non-genomic regulation of lipogenic and oxidative pathways. J Biol Chem 280: 35983–35991, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dahlman-Wright K, Cavailles V, Fuqua SA, Jordan VC, Katzenellenbogen JA, Korach KS, Maggi A, Muramatsu M, Parker MG, Gustafsson JA. International Union of Pharmacology. LXIV. Estrogen receptors. Pharmacol Rev 58: 773–781, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gao H, Bryzgalova G, Hedman E, Khan A, Efendic S, Gustafsson JA, Dahlman-Wright K. Long-term administration of estradiol decreases expression of hepatic lipogenic genes and improves insulin sensitivity in ob/ob mice: a possible mechanism is through direct regulation of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3. Mol Endocrinol 20: 1287–1299, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Geiger PC, Han DH, Wright DC, Holloszy JO. How muscle insulin sensitivity is regulated: testing of a hypothesis. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 291: E1258–E1263, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gower BA, Munoz J, Desmond R, Hilario-Hailey T, Jiao X. Changes in intra-abdominal fat in early postmenopausal women: effects of hormone use. Obesity (Silver Spring) 14: 1046–1055, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gupte AA, Bomhoff GL, Geiger PC. Age-related differences in skeletal muscle insulin signaling: the role of stress kinases and heat shock proteins. J Appl Physiol 105: 839–848, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gupte AA, Bomhoff GL, Morris JK, Gorres BK, Geiger PC. Lipoic acid increases heat shock protein expression and inhibits stress kinase activation to improve insulin signaling in skeletal muscle from high-fat-fed rats. J Appl Physiol 106: 1425–1434, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gupte AA, Bomhoff GL, Swerdlow RH, Geiger PC. Heat treatment improves glucose tolerance and prevents skeletal muscle insulin resistance in rats fed a high-fat diet. Diabetes 58: 567–578, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Haim S, Shakhar G, Rossene E, Taylor AN, Ben-Eliyahu S. Serum levels of sex hormones and corticosterone throughout 4- and 5-day estrous cycles in Fischer 344 rats and their simulation in ovariectomized females. J Endocrinol Invest 26: 1013–1022, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Han X, Ploug T, Galbo H. Effect of diet on insulin- and contraction-mediated glucose transport and uptake in rat muscle. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 269: R544–R551, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Heine PA, Taylor JA, Iwamoto GA, Lubahn DB, Cooke PS. Increased adipose tissue in male and female estrogen receptor-alpha knockout mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 12729–12734, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hirosumi J, Tuncman G, Chang L, Gorgun CZ, Uysal KT, Maeda K, Karin M, Hotamisligil GS. A central role for JNK in obesity and insulin resistance. Nature 420: 333–336, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Imaoka M, Kato M, Tago S, Gotoh M, Satoh H, Manabe S. Effects of estradiol treatment and/or ovariectomy on spontaneous hemorrhagic lesions in the pancreatic islets of Sprague-Dawley rats. Toxicol Pathol 37: 218–226, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jiang L, Wang Q, Yu Y, Zhao F, Huang P, Zeng R, Qi RZ, Li W, Liu Y. Leptin contributes to the adaptive responses of mice to high-fat diet intake through suppressing the lipogenic pathway. PLoS ONE 4: e6884, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kahn BB, Pedersen O. Suppression of GLUT4 expression in skeletal muscle of rats that are obese from high fat feeding but not from high carbohydrate feeding or genetic obesity. Endocrinology 132: 13–22, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kanaya AM, Herrington D, Vittinghoff E, Lin F, Grady D, Bittner V, Cauley JA, Barrett-Connor E. Glycemic effects of postmenopausal hormone therapy: the Heart and Estrogen/progestin Replacement Study A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 138: 1–9, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kusunoki M, Storlien LH, MacDessi J, Oakes ND, Kennedy C, Chisholm DJ, Kraegen EW. Muscle glucose uptake during and after exercise is normal in insulin-resistant rats. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 264: E167–E172, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lundholm L, Bryzgalova G, Gao H, Portwood N, Falt S, Berndt KD, Dicker A, Galuska D, Zierath JR, Gustafsson JA, Efendic S, Dahlman-Wright K, Khan A. The estrogen receptor-α-selective agonist propyl pyrazole triol improves glucose tolerance in ob/ob mice: potential molecular mechanisms. J Endocrinol 199: 275–286, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Margolis KL, Bonds DE, Rodabough RJ, Tinker L, Phillips LS, Allen C, Bassford T, Burke G, Torrens J, Howard BV. Effect of oestrogen plus progestin on the incidence of diabetes in postmenopausal women: results from the Women's Health Initiative Hormone Trial. Diabetologia 47: 1175–1187, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Muraki K, Okuya S, Tanizawa Y. Estrogen receptor alpha regulates insulin sensitivity through IRS-1 tyrosine phosphorylation in mature 3T3–L1 adipocytes. Endocr J 53: 841–851, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nagira K, Sasaoka T, Wada T, Fukui K, Ikubo M, Hori S, Tsuneki H, Saito S, Kobayashi M. Altered subcellular distribution of estrogen receptor alpha is implicated in estradiol-induced dual regulation of insulin signaling in 3T3–L1 adipocytes. Endocrinology 147: 1020–1028, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Paquette A, Shinoda M, Rabasa Lhoret R, Prud'homme D, Lavoie JM. Time course of liver lipid infiltration in ovariectomized rats: impact of a high-fat diet. Maturitas 58: 182–190, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pedersen O, Kahn CR, Flier JS, Kahn BB. High fat feeding causes insulin resistance and a marked decrease in the expression of glucose transporters (Glut 4) in fat cells of rats. Endocrinology 129: 771–777, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pfeilschifter J, Koditz R, Pfohl M, Schatz H. Changes in proinflammatory cytokine activity after menopause. Endocr Rev 23: 90–119, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Phrakonkham P, Viengchareun S, Belloir C, Lombes M, Artur Y, Canivenc-Lavier MC. Dietary xenoestrogens differentially impair 3T3–L1 preadipocyte differentiation and persistently affect leptin synthesis. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 110: 95–103, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ramadoss P, Unger-Smith NE, Lam FS, Hollenberg AN. STAT3 targets the regulatory regions of gluconeogenic genes in vivo. Mol Endocrinol 23: 827–837, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Riant E, Waget A, Cogo H, Arnal JF, Burcelin R, Gourdy P. Estrogens protect against high-fat diet-induced insulin resistance and glucose intolerance in mice. Endocrinology 150: 2109–2117, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ribas V, Nguyen MT, Henstridge DC, Nguyen AK, Beaven SW, Watt MJ, Hevener AL. Impaired oxidative metabolism and inflammation are associated with insulin resistance in ERa-deficient mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 298: E304–E319, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ropelle ER, Pauli JR, Prada PO, de Souza CT, Picardi PK, Faria MC, Cintra DE, Fernandes MF, Flores MB, Velloso LA, Saad MJ, Carvalheira JB. Reversal of diet-induced insulin resistance with a single bout of exercise in the rat: the role of PTP1B and IRS-1 serine phosphorylation. J Physiol 577: 997–1007, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Rosholt MN, King PA, Horton ES. High-fat diet reduces glucose transporter responses to both insulin and exercise. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 266: R95–R101, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Saltiel AR, Kahn CR. Insulin signaling and the regulation of glucose and lipid metabolism. Nature 414: 799–806, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sevilla L, Guma A, Enrique-Tarancon G, Mora S, Munoz P, Palacin M, Testar X, Zorzano A. Chronic high-fat feeding and middle-aging reduce in an additive fashion Glut4 expression in skeletal muscle and adipose tissue. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 235: 89–93, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sites CK, Toth MJ, Cushman M, L'Hommedieu GD, Tchernof A, Tracy RP, Poehlman ET. Menopause-related differences in inflammation markers and their relationship to body fat distribution and insulin-stimulated glucose disposal. Fertil Steril 77: 128–135, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Storlien LH, James DE, Burleigh KM, Chisholm DJ, Kraegen EW. Fat feeding causes widespread in vivo insulin resistance, decreased energy expenditure, and obesity in rats. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 251: E576–E583, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Tremblay F, Lavigne C, Jacques H, Marette A. Defective insulin-induced GLUT4 translocation in skeletal muscle of high fat-fed rats is associated with alterations in both Akt/protein kinase B and atypical protein kinase C (zeta/lambda) activities. Diabetes 50: 1901–1910, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Young DA, Uhl JJ, Cartee GD, Holloszy JO. Activation of glucose transport in muscle by prolonged exposure to insulin. Effects of glucose and insulin concentrations. J Biol Chem 261: 16049–16053, 1986 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Yuan M, Konstantopoulos N, Lee J, Hansen L, Li ZW, Karin M, Shoelson SE. Reversal of obesity- and diet-induced insulin resistance with salicylates or targeted disruption of Ikkbeta. Science 293: 1673–1677, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Zierath JR, Houseknecht KL, Gnudi L, Kahn BB. High-fat feeding impairs insulin-stimulated GLUT4 recruitment via an early insulin-signaling defect. Diabetes 46: 215–223, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]