Abstract

We investigated the functional architecture of the inferior colliculus (IC) in rhesus monkeys. We systematically mapped multiunit responses to tonal stimuli and noise in the IC and surrounding tissue of six rhesus macaques, collecting data at evenly placed locations and recording nonresponsive locations to define boundaries. The results show a modest tonotopically organized region (17 of 100 recording penetration locations in 4 of 6 monkeys) surrounded by a large mass of tissue that, although vigorously responsive, showed no clear topographic arrangement (68 of 100 penetration locations). Rather, most cells in these recordings responded best to frequencies at the low end of the macaque auditory range. The remaining 15 (of 100) locations exhibited auditory responses that were not sensitive to sound frequency. Potential anatomical correlates of functionally defined regions and implications for midbrain auditory prosthetic devices are discussed.

Keywords: topography, tonotopy, prosthetic, auditory midbrain implant

maps of how neural response properties vary, as a function of the location within a brain structure can provide a useful bridge between neurophysiology and anatomy. Also referred to as functional architecture, such maps allow the activity of a neuron to be interpreted in light of its putative inputs and outputs. Response maps are also useful for guiding the placement of neural prosthetics [e.g., Wessberg et al. (2000)]. The inferior colliculus (IC) has recently emerged as a candidate structure for such prosthetics (Colletti et al. 2007; Colletti et al. 2009; Lim and Anderson 2006, 2007; Lim et al. 2009; Lim et al. 2008), so understanding the geographical arrangement of response properties in this structure can provide guidance for implant placement.

The IC is a principal site of convergence along the auditory pathway. Virtually all ascending auditory information passes through the IC on the way to thalamus (Aitkin and Phillips 1984), and so it is an especially important locus to investigate functional maps. The tonotopic organization, or orderly progression of frequency tuning properties, has been studied in a wide variety of animals [e.g., rats (Clopton and Winfield 1973; Kelly et al. 1991); cats (Aitkin et al. 1975; Merzenich and Reid 1974; Rose et al. 1963); guinea pigs (Malmierca et al. 1995); mice (Stiebler and Ehret 1985); ferrets (Moore et al. 1983); owls (Knudsen and Konishi 1978); and bats (Casseday and Covey 1992; Miller et al. 2005; Poon et al. 1990; Zook et al. 1985)].

However, little is known about the functional map of the IC in primates. Macaques provide an excellent model for human hearing, as both humans and macaques rely greatly on audition for communication and the frequency ranges heavily overlap: ∼30 Hz to 30 kHz for monkeys (Pfingst et al. 1975; Pfingst et al. 1978; Stebbins et al. 1966) and 20 Hz to 20 kHz for humans (Moore 2008). Studies in monkeys also offer advantages not directly related to audition: monkeys are readily trained, and phenomena such as eye movements that cannot be studied in other mammals can be studied in monkeys [e.g., Groh et al. (2001); Porter et al. (2006); Zwiers et al. (2004)]. Functional maps are essential to guide this work.

No detailed map of the monkey IC yet exists. Ryan and Miller (1978) recorded the auditory responses of single units along penetrations through the macaque IC but did not collect data with uniform spacing between recordings and primarily sampled neurons in the most central region. Zwiers et al. (2004) also recorded the responses of single units from the macaque IC and noted the depth of recordings. Location in the horizontal plane was not systematically varied in this study, and the majority of recordings were thought to have been taken from a similar central region as in the study by Ryan and Miller (1978).

Accordingly, we performed a systematic mapping of auditory responses throughout the midbrains of six unanesthetized rhesus monkeys. We presented a series of randomly interleaved sounds as we recorded multiunit activity (MUA; the times of action potentials of small clusters of neurons). MUA provides an estimate of local activity and serves as an ideal measurement, as recording locations can be predefined (unlike single unit activity where fine movement of the electrode is necessary for isolating individual waveforms). We collected data in sessions in which we lowered an electrode in 0.5-mm increments through the midbrain. Over sessions we varied the anterior/posterior and medial/lateral trajectory of our electrodes in 1-mm increments. In this manner, we formed a map of the entire region, collecting data from the IC and surrounding tissue.

In each monkey, we found a large region with neurons that showed vigorous, short latency responses to auditory stimuli. In four of six monkeys, we found a tonotopic area in which recording penetrations showed an orderly progression of tuning frequencies as the electrode passed through the IC. Surrounding this area was a large nontonotopic region. In these penetrations, neurons generally showed the most powerful response to low frequencies, a bias that has not been identified previously. Neurons in the low frequency region generally showed more transient and slower responses than those in the tonotopic area. Finally, a small subset of recordings on the periphery of the responsive area showed little or no tuning to tone frequency. We conclude that in the awake monkey auditory neurons surrounding the central (tonotopic) area show a powerful bias toward low frequencies.

METHODS

Surgical Preparation, Recording Procedures, and Inclusion Criteria

Three male and three female rhesus monkeys participated in the experiments. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Dartmouth College and Duke University and were conducted in accordance with the Principles of Laboratory Animal Care of the National Institutes of Health (publication 86-23, revised 1985). Surgical procedures were performed using isoflurane anesthesia and aseptic techniques, as well as postoperative analgesia. The monkeys underwent an initial surgery to implant a head post for restraining the head and a scleral eye coil for monitoring eye position (Judge et al. 1980; Robinson 1963). After recovery, an additional surgery was performed to make a craniotomy and to implant a recording cylinder positioned over the left IC. The cylinder was oriented to allow electrodes to approach the IC at an angle ∼30° from vertical in the coronal plane, i.e., proceeding from dorsolateral to ventromedial (Groh et al. 2003; Porter et al. 2007). For simplicity and convenience, we will usually refer to the affected dimensions as lateral/medial and dorsal/ventral (or above/below), despite their tilt (i.e., in the axis defined by the recording chamber). The chamber contained a fixed grid of holes (Crist Instruments, Gaithersburg, MD) aligned such that electrode penetrations could be made in 1-mm increments in the anterior/posterior and medial/lateral dimensions. Recordings were made using tungsten microelectrodes (1–3 MΩ; FHC, Bowdoin, ME). Multiunit clusters were selected using a window discriminator (monkeys A and W: Plexon, Dallas, TX; monkeys E, M, C, and X: Bak Electronics, Germantown, MD), and spike times were stored for off-line analysis.

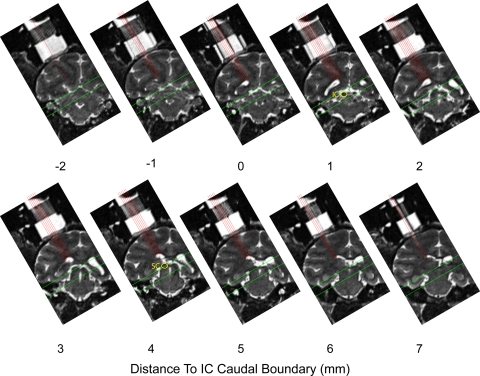

The location of the IC was determined using an anatomical MRI scan in which the recording chamber and plastic grid could be visualized. Several marker electrodes were placed in the plastic grid. Images were then aligned precisely along the axis of the grid, such that recording locations could be mapped directly onto anatomical landmarks visible in MRI. Using MRI, we estimated all of the borders of the IC except on the rostral aspect, where a clear definition was not visible. In each monkey, we recorded from a patch around the estimated IC location, making a series of electrode penetrations through the holes in the recording grid. We lowered electrodes along the dorsolateral/ventromedial axis of the IC (established by the placement of the recording cylinder) and recorded from multiunit clusters every 0.5 mm along the trajectory of the penetration. Figure 1 shows MR images spanning the recorded region of monkey A, the most thoroughly sampled monkey in our data set. The images are spaced in 1-mm increments, such that each image corresponds to a row of recordings in the anterior/posterior aspect of the recording grid. The locations of recording trajectories (medial/lateral aspect of the recording grid) have been plotted with red lines. We began and ended recording sessions at depths above and below the putative IC to ensure that the entire structure was covered but limited our analysis to locations between the borders measured from the MRI scans, ±1.5 mm. This constraint is indicated with green lines of Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Locations mapped in monkey A illustrated on MR images. A series of coronal MR images spanning the 10- mm range that was sampled physiologically. Voxels were 0.5-mm cubes. Images were rotated into the plane of recording by placing electrodes in the recording grid, visible ∼0 and 7 mm. Each panel corresponds to a single mediolateral row of grid locations at a given position in the anterior/posterior dimension (interleaved coronal slices are not displayed). Red lines indicate the approach of each of the recording penetrations in the medial/lateral dimension. Green lines indicate the targeted area; recordings shallower and deeper than these borders were discarded. Locations of the inferior colliculus (IC) and superior colliculus (SC) are indicated on 2 of the panels.

Some recording grid locations were sampled multiple times on different days to verify that the results for those holes were reproducible across sessions. Table 1 lists both raw totals and totals with duplicate penetrations excluded. Duplicate penetrations were also excluded for analyses related to the proportion of IC tissue that shows a particular property. Such cases are specifically noted as they arise. Unless otherwise mentioned, analyses were conducted on the complete data set without excluding the duplicates.

Table 1.

Quantity and categorization of recordings

|

Monkey |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | W | E | M | C | X | Total | |

| Recorded | |||||||

| Penetrations | 59 | 50 | 51 | 74 | 42 | 74 | 350 |

| Sites | 646 | 534 | 694 | 588 | 457 | 790 | 3709 |

| Responsive | |||||||

| Penetrations | 45 | 27 | 13 | 11 | 15 | 14 | 125 |

| Sites | 247 | 134 | 61 | 49 | 71 | 77 | 639 |

| Penetration category | |||||||

| Untuned | 16 (10) | 4 (3) | 1 (1) | 0 | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | 23 (15) |

| Tuned* | 22 (21) | 13 (11) | 12 (9) | 6 (6) | 9 (7) | 14 (14) | 76 (68) |

| Tonotopic | 7 (5) | 10 (5) | 0 (0) | 5 (4) | 4 (3) | 0 (0) | 26 (17) |

Total number of recorded and responsive locations is shown, along with the number assigned to each penetration category as described in methods and shown in Fig. 5. In cases where penetration locations were sampled more than once, both the raw totals and the number of unique penetration locations are shown. If any tonotopic penetrations were observed at a given grid location, the location was marked as tonotopic; if any tuned penetrations were observed, the location was marked as tuned. Numbers in parentheses indicate quantities of unique penetration locations.

Excluding tonotopic penetrations.

Data were analyzed offline to determine which sites along a penetration showed auditory responses. The times of action potentials were binned in 1-ms windows aligned on stimulus onset to form a peristimulus time histogram (PSTH) for all auditory stimuli presented. The PSTH was then smoothed using a 5-ms moving average. A site was marked as auditory if the smoothed PSTH exceeded 3 SDs above baseline for 10 consecutive ms in a 50-ms window following stimulus onset. We further restricted analysis to penetrations that contained three or more responsive sites. Finally, as noted above, we excluded responsive sites that were >1.5 mm shallower or deeper than anatomical estimates gathered from MRI (borders for monkey A indicated on Fig. 1). The objective marking of auditory stretches through the IC corresponded well with subjective markings based on inspection of PSTHs and tuning curves, and locations agreed well with anatomical indications from MRI and histological reconstruction in monkeys W and X detailed below.

We tested a subset of sites in monkey A, notably those in the rostral-most penetrations, with microstimulation to rule out that they were in the superior colliculus (SC). The SC is an oculomotor structure rostral and dorsal to the IC, and it exhibits auditory responsiveness (Jay and Sparks 1984; Populin et al. 2004). However, the SC's auditory activity is quite weak when the animal is not engaged in a task involving saccades to auditory stimuli (Jay and Sparks 1987a,b). Our monkeys were not performing an auditory saccade task, so we did not expect to see, nor did we observe, strong auditory responses in the SC. Occasionally, sites with weak auditory responses in the vicinity of the SC were observed, but these were generally excluded from our IC sample by either the MRI or because firing rate changes did not meet the response threshold described above. Stimulation allowed us to confirm that these exclusion criteria were adequate: only 2 of 51 sites included for analysis of auditory characteristics showed saccades following stimulation onset, confirming that the inclusion criteria successfully excluded the SC. Instead, when saccades were observed, they were evoked following stimulation at sites dorsal to the IC, consistent with some penetrations passing through the intermediate and deep layers of the SC on the way to the underlying IC.

Stimulus Presentation

Experiments were conducted in complete darkness in a single-walled IAC sound isolation booth. Echo-absorbent material lined the walls and ceiling (3-in. Sonex Painted One acoustic foam), as well as the floor (carpet). Auditory stimuli consisted of tones of 16 frequencies ranging from 0.4 to 12 kHz (approximately one-fourth octave increments), as well as broadband noise (spectrum ranging from 0.5 to 18 kHz). In monkey W, we recorded several sites in which included the presentation of eight additional frequencies ranging from 0.1 to 0.33 kHz. In monkeys A and W, sounds were presented for 200 ms and in all other recordings sounds were presented for 500 ms. All sounds were initiated with a 10 ms on ramp. At each recording site, 200 total trials (more in cases where we presented additional frequencies) were presented in a randomly interleaved fashion (∼12 trials per stimulus).

Sounds were generally presented using loudspeakers (Audax Model TWO25V2 or Bose Acoustimas cube speakers) located 90° contralateral to the recording chamber and 57 inches from the subject's head. In all monkeys, sounds were presented at 50 dB sound pressure level. Sound levels were calibrated to within 1 dB of the target amplitude using a sound meter (Brüel & Kjær; model 2237 with model 4137 condenser microphone; A-weighted) placed at the position that the monkey's head would occupy in the experiment. Sound spectra are shown in (see Supplemental Materials, Supplemental Fig. S9; Supplemental Material for this article is available online at the J Neurophysiol website). Eye position was monitored throughout the experiment, and the monkey was woken if drifting eye movements characteristic of sleep were observed. In monkeys A, W, E, and M, an unrelated nonauditory task was run at some recording sites as part of a separate experiment, not described here. These trials were run in separate blocks after frequency information was collected at a given depth.

Data Analysis

Frequency tuning.

To characterize frequency tuning, we counted spikes in a 200-ms window following sound onset and compared it to a 200-ms baseline period before the sound. We computed this response for each of the different stimulus frequencies, i.e., an (isointensity) frequency response curve. Gaussian curves were then fit to the responses as a function of the logarithm of the stimulus frequency. Fitting of Gaussian functions was performed in Matlab (Mathworks, Natick MA) using the “fit” function. Gaussian fits were constrained to have peaks in the range of frequencies tested. The best frequency (BF) was labeled as the frequency corresponding to the peak of the Gaussian curve, provided the Gaussian successfully described the data (P < 0.05, F-test). Sites for which Gaussians did not fit showed no apparent tuning by inspection and were included only for analysis of nontuning related features. Gaussian defined BFs were similar to the frequency evoking the maximum response (an alternative measure of BF) but allowed us to take into consideration the responses of neighboring frequencies in estimating BF. Penetrations were classified as tuned if three or more sites were fit by Gaussian functions. Penetrations with fewer were classified as untuned. Such penetrations could include either sites not very responsive to tones or responsive to tones but insensitive to their frequency.

Tuned penetrations were tested for the presence of a tonotopic progression by relating the BF to depth with a linear regression. Because each BF measurement reflected ∼200 trials, treating them as a single data point in the regression would cause an underestimate of the true confidence intervals around the regression slope. Accordingly, we performed a Monte Carlo simulation. For each penetration, we ran 100 iterations in which we randomly selected 75% of the trials for each multiunit cluster and fit Gaussian tuning curves to each of the data subsets. We then fit regression lines to log(BF) vs. depth for each of iterations. This process allowed us to create a 95% confidence interval for the slopes of regression lines without making any assumptions about the distribution of slopes. Based on previous studies in monkeys and other mammals, we expected BF to increase with depth [e.g., in monkey: FitzPatrick (1975); Ryan and Miller (1978); Zwiers et al. (2004)]. We defined tonotopic penetrations as those in which 95% of slopes from the Monte Carlo simulation were positive. Only significant Gaussian fits were used in the simulation, and on some iterations there were insufficient fits to perform a regression. Only penetrations that had at ≥75 successful iterations were included. This analysis matched our subjective marking of tonotopy by visual inspection of the responses as a function of sound frequency over the course of a penetration.

Temporal profile.

To characterize the temporal profile of the response, we measured the firing rate in two windows. We defined the sustained response as the average firing rate in a period 100–200 ms following stimulus onset and the transient response as the average firing rate in a 20-ms period centered on the peak of the PSTH over the first 50 ms following stimulus onset. Firing rates in both windows were converted to z-scores relative to the mean and SD of the firing rate during a baseline period (0 to 200 ms before sound onset).

To compare the response profile across recordings, we created a response profile index (RPI):

This index provides a metric for how sustained a response is: sites that exhibit almost no sustained responses produce RPI values ∼1, whereas sites with sustained responses similar in magnitude to transient responses produce RPI values near 0 (the RPI could exceed 1 if an excitatory transient was followed by an inhibitory sustained component).

Latency.

Latency was defined as the time (with respect to stimulus onset) that the PSTH exceeded 3 SDs of baseline. Because stimuli were generally presented from loudspeakers, latency included the time it took for the sound to travel to the ear, ∼4 ms, (i.e., to convert to latency from the arrival of the sound at the ear to the neural response, subtract ∼4 ms).

Histology

In monkeys W and X, at the conclusion of recordings, an electrolytic lesion was made along a central penetration. The animal was perfused, and the brain was fixed with formalin. In monkey W, the brain was sliced in 60-μm coronal sections stained with cytochrome oxidase, and in monkey X, 50-μm sections were cut and stained with cresyl violet. The histological analysis of monkey W was performed by the Cant Laboratory at Duke University and that of monkey X was performed by the Winer Laboratory at the University of California, Berkeley.

Sources of Error in Determining Recording Locations

Certain sources of error affected the reliability of our estimate of recording location. The most reliable measurement is the depth within a penetration. The accuracy of this measurement is on the order of micrometers, i.e., the accuracy of our microdrive (Narishige; model MO-951). The overall depth is estimated less accurately. There are two sources of error here. The first is that a paint mark is placed at a measured position on each electrode before they are placed in the microdrive. The mark is then aligned with the scale on the microdrive. The precision of this paint mark and its alignment are on the order of ∼1 mm or so. The second issue is the head implant itself, which can gradually lift over time as tissue grows beneath the acrylic, moving the cylinder slightly. These changes are small and slow. However, the more time that elapses, the less fidelity there is between the overall depth estimate and that predicted from the MRI scan (which was typically done once before the mapping began). It was to allow for these sources of error that we included a 1.5-mm buffer zone above and below the estimated depth of the IC. Overall, the depth measurements of responsive sites corresponded well to the predicted depth of the IC, suggesting that these sources of error were largely variable and not systematic errors. As noted above, a number of penetration locations were sampled repeatedly, and the results were qualitatively consistent across multiple penetrations, providing further evidence that changes due to shifting of the implant were minimal.

Potential error in the AP and ML dimensions arises due to head cap shifting, as mentioned above, and also electrode bending as the IC is approached. The IC is ∼5 cm below the top of our recording grid. Part of this distance was traversed with the electrode in a rigid guide tube, but at least the last centimeter was traversed by the electrode alone. The tungsten electrodes could bend as the approached the IC or could potentially slip alongside it especially on the lateral aspect. This source of error probably accounts for a <1-mm variation in the precise AP or ML position of electrode on repeated penetrations through the same grid location.

Sources of error in MRI reconstruction relate to the quality of the image and voxel size: the thickness of coronal slices ranged between 0.5 and 1 mm, and the other two dimensions were fixed at 0.5 mm across scans. The visibility of morphological features of the IC on the scan and our ability to estimate the position of the cylinder and electrodes on the scan also influence the accuracy with which recording locations could be reconstructed. Reconstructing the borders of the IC via MRI scan using similar techniques has been estimated to be accurate to the nearest 1 mm (Kalwani et al. 2009).

RESULTS

We systematically mapped the IC of six monkeys by recording multiunit activity along electrode penetrations through the structure while presenting a series of auditory stimuli. We classified penetrations based on responsiveness to tones: penetrations showing auditory responses were classified as either tuned or untuned, and tuned penetrations were further classified based on whether or not they showed a tonotopic progression (Table 1).

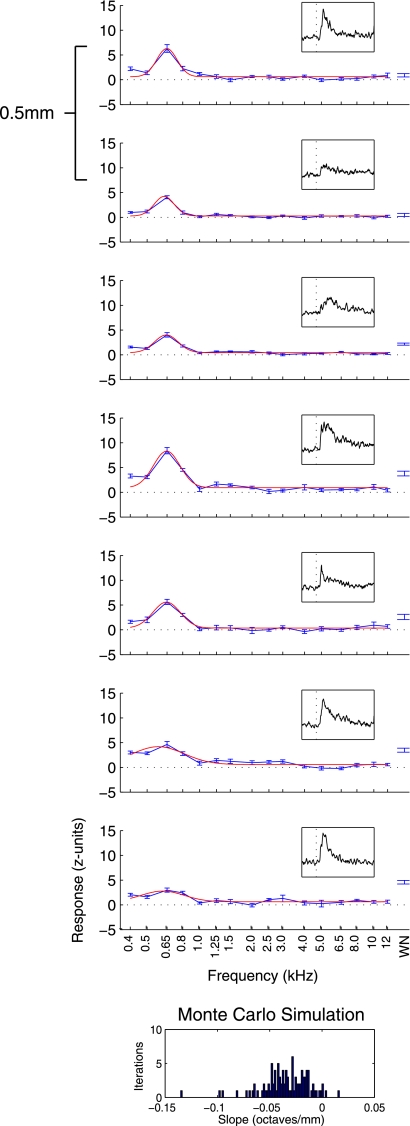

Figure 2 shows an example tuned, nontonotopic, penetration, the type we observed most frequently (in 68 of 100 auditory-responsive penetrations, numbers from reduced data set with 1 penetration per grid hole). The average response in each condition (the mean firing rate in a 200-ms period following stimulus onset, normalized to baseline) is plotted against the stimulus. The recordings are plotted in the order they were taken, with the shallowest recordings at the top and the deepest recordings at the bottom. Only the responsive recordings are shown, although nonresponsive recordings flanked the auditory area above and below. Gaussian fits to the data, used below to summarize tuning, are overlaid. The recordings at each of the depths showed clear auditory responses [an increase in the height of the PSTH (shown in the inset on each tuning curve following stimulus onset)] that were strongly tuned to low frequencies (∼650 Hz). At the deepest recording, only a small response to tones is seen, although this site responded well to broadband white noise.

Fig. 2.

Responses from a tuned penetration. Average response over a 200-ms period following baseline (normalized by subtracting the mean and dividing by the SD of the activity during the baseline period) is plotted in blue as a function of sound frequency (i.e., isointensity frequency response curves). Error bars indicate SE. Topmost panel shows the shallowest recording in this penetration, with each panel thereafter being 0.5 mm deeper. A Gaussian curve (red line) was fit to data from tone trials. Location of the peak of this curve was labeled as best frequency (BF), which remained low throughout this penetration. At the extreme right, the average and SE of responses to presentations of broadband white noise are shown. Insets: peristimulus time histogram (PSTH) across stimuli for a period ranging from 50 ms before to 200 ms after stimulus onset. Below the tuning data, results from a Monte Carlo analysis to probe for tonotopy indicate that this penetration did not show an increase in BF with deeper recordings: the slopes are not biased towards positive values. WN, white noise.

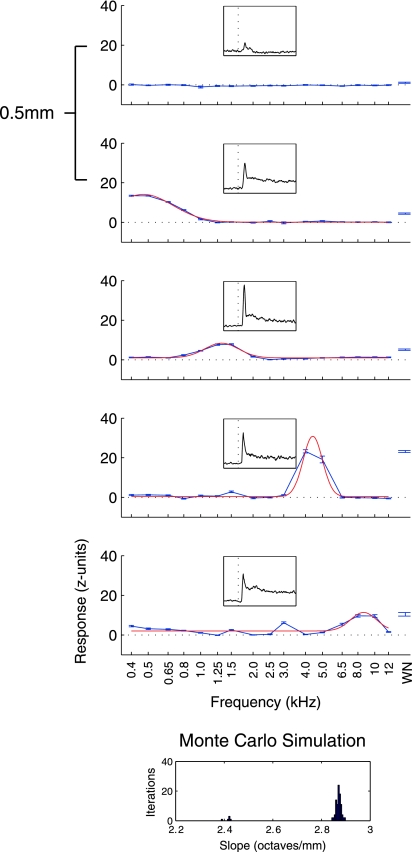

Tonotopic penetrations were more rare, found in 17 of 100 auditory-responsive penetration locations. Figure 3 shows data from an example tonotopic penetration in the same format as Fig. 2. Sites along this penetration, in contrast to the nontonotopic example, exhibit an orderly increase in BF. The first responsive recording in this penetration showed only a small response and no clear tuning (this site responded best to white noise). The second site was tuned to the lowest frequency sounds we presented; deeper sites showed maximal responses to progressively higher frequencies. To objectively determine the tonotopicity of penetrations, we performed a Monte Carlo simulation, calculating regressions on the slope of BF over depth on randomly selected subsets of the data at each site (see methods for details). Figure 3, inset, shows a histogram of the slopes of regressions over the simulation for this penetration. Sites were marked as tonotopic if 95% of the slopes were positive (in this example, all iterations showed positive slopes in contrast to the example in Fig. 2, which showed no such trend; note the very different x-axis scales for these 2 insets).

Fig. 3.

Frequency responses from a tonotopic penetration. Plotted in the same format as Fig. 2; the panels show an increase in BF with deeper recordings. All iterations of the Monte Carlo analysis used to detect tonotopy showed positive slopes. (note the different scale on the x-axis as compared with Fig. 2).

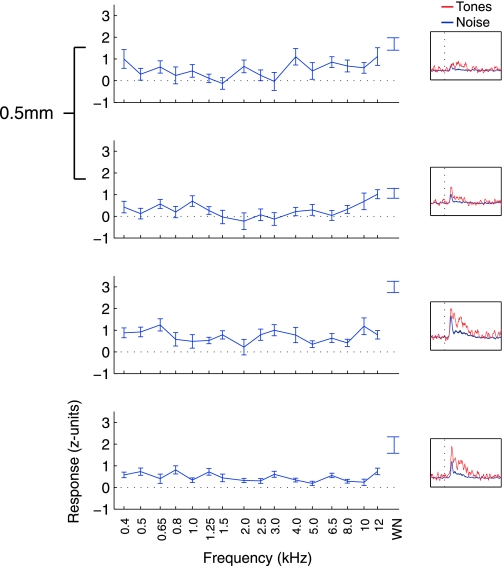

Figure 4 shows the responses of an untuned recording. Untuned penetrations (defined as having <3 sites showing tuned responses) were uncommon and only found at the most peripheral sites sampled. Lack of tuning occurred when sites responded to tones without clear modulation based on tone frequency or when the sites responded only to presentations of broadband white noise. Most of the untuned recordings in our sample showed some response to tones (120 of 185 sites; P < 0.05, t-test), but several only responded to white noise (49 of 185 sites). The example in Fig. 4 shows a penetration in which all of the sites responded to tonal stimuli (P < 0.05, t-test on tone trials) but showed no clear preference for frequency among these responses. Responses to white noise were larger than those of tones (red trace compared with blue trace in PSTH inset), particularly at the two deepest sites, as would be expected of neurons with broad tuning characteristics.

Fig. 4.

Frequency responses from an untuned penetration. Plotted in the same format as Fig. 2; this penetration showed no clear tuning. Gaussian curves did not fit the data and so are not plotted. Sites in this penetration responded to tones but did not prefer a group of tone frequencies over others. Here, the PSTH insets show firing rate changes over time separately for noise (red trace) and tone (blue trace) trials. No inset is shown for the Monte Carlo analysis used to detect tonotopy, as this analysis could not be run on untuned penetrations.

To be sure that sites showing only transient responses to tones were not mistakenly labeled as untuned due to the large window used for assessing tuning (for example, note the relatively weak sustained component of the responses shown in the PSTH insets of Fig. 4), we repeated the Gaussian fitting procedure using a shorter spike-counting window (10–50 ms following stimulus onset). The majority of sites that showed tuning in one window also showed tuning in the other (405 of 520 sites showed tuning in both windows, 66 showed tuning only in the shorter window, 49 showed tuning only in the longer window). At tuned sites, estimates of BF were highly similar (P > 0.05, t-test; Supplemental Fig. S1).

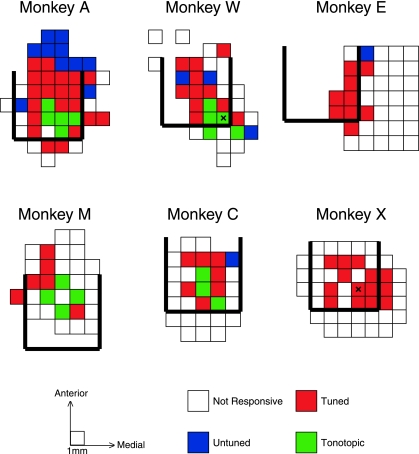

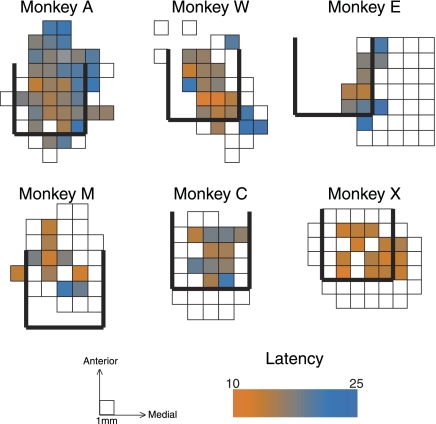

Top-down maps of the categories of penetrations for each monkey are shown in Fig. 5. Each square in the maps corresponds to a single recording penetration location. The rows in the map for monkey A correspond to the panels shown in Fig. 1, with the columns within each row matching the electrode trajectories. In each monkey, we collected data from a region showing auditory responses, surrounded to some extent by recordings from nonresponsive cells. Responsive locations agreed well with estimates of the posterior, caudal, and medial boundaries determined using MRI ±1 mm (thick black lines). For grid holes with multiple penetrations, only the most tonotopic, tuned, or responsive penetration is depicted here. Supplemental Figs. S2–7 show the raw data used to generate these maps.

Fig. 5.

Maps of responsive, tuned, and tonotopic penetrations. Maps of penetration locations (i.e., the horizontal plane of the recording chamber) for each monkey. Each box in the maps displays information for a single location in the recording chamber (boxes from monkey A correspond to the red lines displayed in Fig. 1). Unfilled boxes indicate locations in which auditory responses were not found. Blue, red, and green boxes mark the locations of responsive (but untuned), tuned (but nontonotopic), and tonotopic recording penetrations. On occasions where multiple recordings were made from the same location, the box is colored if any of the penetrations met the criteria to be categorized as tonotopic, tuned, or responsive. Locations marked with an “X” on the maps for monkeys W and X indicate the locations of electrolytic lesions used for histological reconstruction.

Tonotopic, tuned, and untuned penetrations were distributed in a characteristic pattern in the IC. Tonotopic penetrations (green) were only identified in four of six monkeys (monkeys A, W, M, and C), When found, tonotopy tended to be located at or near the caudal extent of the region showing auditory responses or the MRI-identified posterior border. Adjacent to or surrounding the tonotopic penetrations were tuned penetrations (red), which account for the majority of penetrations in all monkeys. Untuned penetrations (blue) were most prominent in monkey A at the rostral extent of our sampling but were occasionally observed in the other monkeys and at other (peripheral) locations.

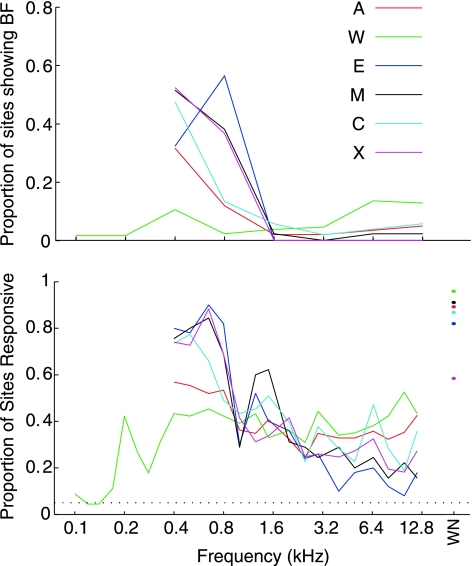

Tuning of Nontonotopic Penetrations

In recording penetrations that did not show a progression from low to high frequencies as the electrode advanced, but did show tuning, most sites responded best to the lowest frequencies we tested. Figure 6, top, shows the distribution of BF values determined by Gaussian fits to the frequency response function data (see methods and examples in Figs. 2–3) in each monkey. The data set for this analysis involved one penetration per location to avoid biasing estimates due to repeated sampling of some locations. With the exception of monkey W, all animals showed a powerful bias toward low frequency BFs throughout recordings. In a subset of recordings from monkey W, we probed for BFs below the range tested in the other animals to determine if this monkey had a low frequency bias but for lower frequencies than the other monkeys, but this did not appear to be the case. The vast majority of data from monkeys A, E, M, C, and X showed the most vigorous response to frequencies <1.6 kHz, several octaves below the upper limit of the monkey's hearing range (Stebbins et al. 1966). This is a surprising result, as no previous experiments have shown such a powerful bias toward low frequency tuning in the monkey, although many other species have auditory neurons that do show a bias toward a specific frequency range [e.g., bat (Kossl and Vater 1985), mole (Muller et al. 1992), and owl (Köppl et al. 1993)].

Fig. 6.

Bias of tuning toward low frequencies throughout recordings. Top: distribution of BF values determined by Gaussian fits to the isointensity frequency response data collected. Lines show the proportion of auditory sites that showed a BF in logarithmically spaced windows. Bottom: proportion of neurons responding to each tested frequency. Both representations of the data indicate a heavy bias toward low frequency selectivity, although B establishes that virtually all of the tested frequencies elicited responses at some sites.

This bias in favor of low frequencies was also observed when the “point image” of activity in response to sound frequency was considered. The point image can be defined as the population response as a function of sound frequency, here expressed as the percentage of neurons responding to each tested frequency. Figure 6, bottom, shows the proportion of sites that responded to each frequency for each monkey. The curves show a strong bias toward low frequency responses, except for those describing the data from monkey W. Importantly, virtually all of the frequencies we tested elicited a response in some sites in each monkey, which reassures that the bias for low frequencies does not reflect complete loss of hearing at high frequencies. The macaque auditory midbrain thus seems to show an enhanced response to low frequencies. Responses to high frequencies are still present, although they rarely exceed the magnitude of their low frequency counterparts. In this manner, high frequency auditory information is not lost despite an amplification of low frequency information.

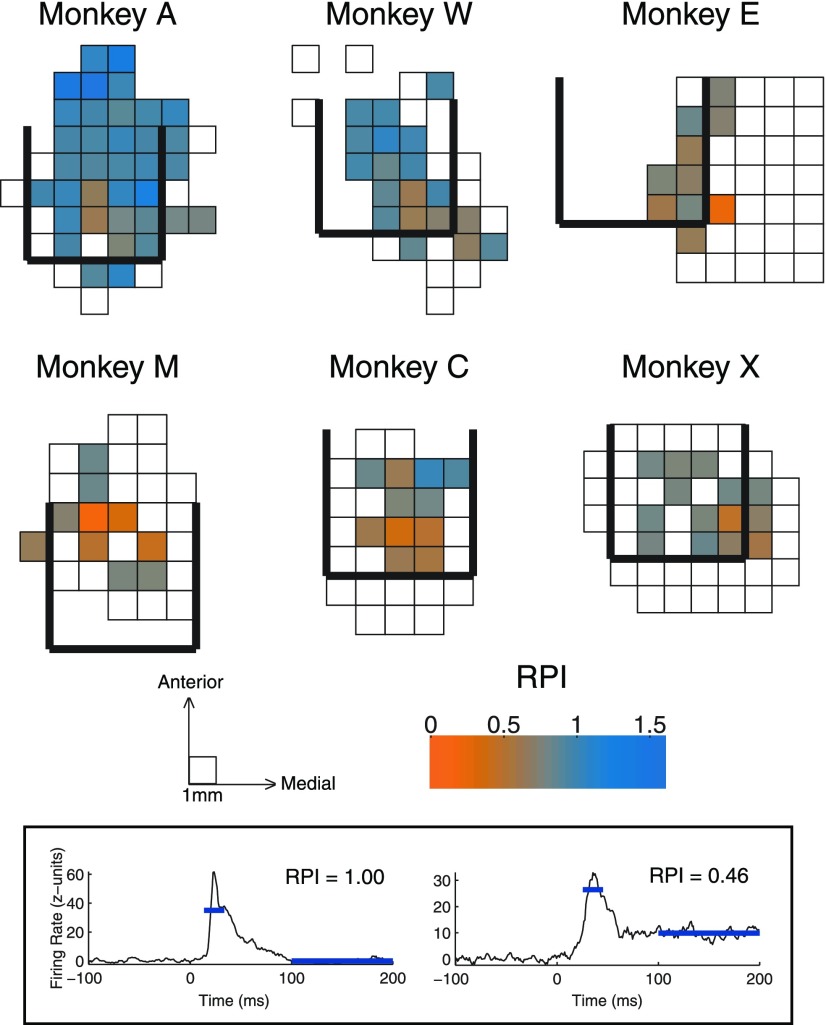

Temporal Response Profile

The temporal profile of a response provides an alternative to tuning characteristics in defining a functional map. The responses we recorded reliably showed an excitatory transient onset element, which was often followed by a sustained response (of varying magnitude) that continued throughout the presentation of the sound. We defined an index to measure the ratio of sustained to transient components (RPI, see methods), to see if response patterns were organized topographically. Figure 7 shows the maps of this index across recording penetrations from each monkey. The measures used for calculating RPI are indicated in the inset with two example PSTHs. Monkeys A and W show a large range in RPI, with the most sustained responses (lower RPI values) in locations near tonotopic penetrations. Monkeys M and C show less variability in response profile but still show a strong coupling between sustained and tonotopic penetrations. The data from monkeys E and X, in which we did not find tonotopy, had surprisingly low RPI values, with responses as sustained as those in tonotopic penetrations in other monkeys.

Fig. 7.

Maps of temporal profile of response in the horizontal plane. Maps follow the format in Fig. 5, here color indicates the average response profile index (RPI) from each penetration location. Lower values of RPI indicate more sustained responses. Inset: time periods used to calculate RPI with the data from two example recordings.

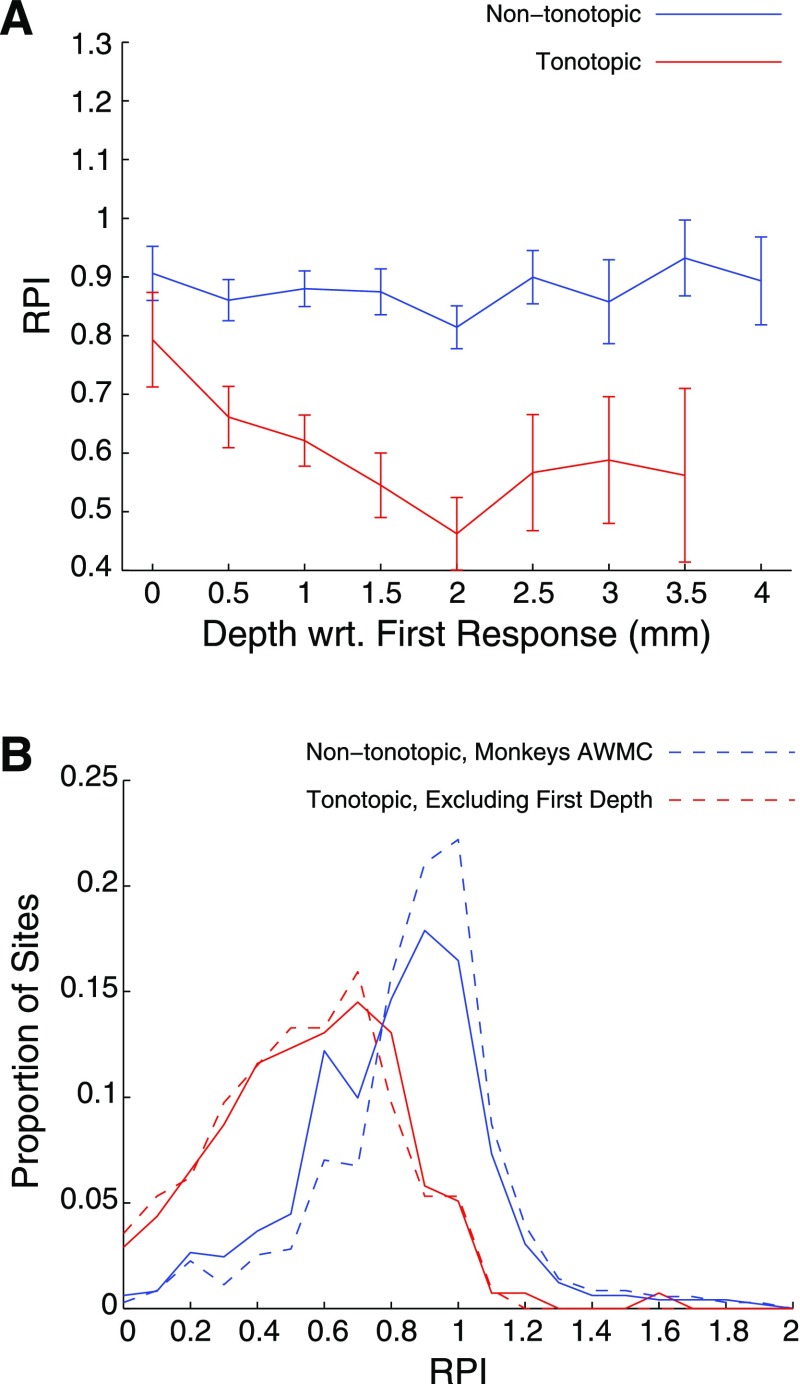

We also observed variation in the response profile within tonotopic penetrations. The example shown in Fig. 3 indicates various levels of sustained responses from depth to depth. The maps in Fig. 7 are collapsed across recording depths, and so topographic effects within electrode penetrations cannot be seen. Figure 8A shows the average RPI across the depth of recordings, relative to the depth of the first auditory response (i.e., entry into the nucleus). Nontonotopic penetrations showed little effect of depth. Conversely, tonotopic penetrations tended to exhibit more transient responses at shallow depths (similar to those of nontonotopic penetrations), while sites recorded deeper showed more sustained responses.

Fig. 8.

RPI distribution for tonotopic and nontonotopic penetrations. A: average RPI at each depth, relative to the first auditory recording within the penetration, for tonotopic (red) and nontonotopic (blue) penetrations. Error bars indicate SE. Distributions of RPI in tonotopic and nontonotopic penetrations (B) overlapped, although tonotopic penetrations generally showed more sustained (i.e., lower RPI) responses. The trend persisted when data from monkeys not showing tonotopy were excluded (blue broken line) or when the shallowest recordings were excluded (red broken line).

Figure 8B shows histograms of RPI from sites in tonotopic and nontonotopic penetrations. While sites within tonotopic penetrations (red solid line) showed RPI values that were skewed toward lower numbers (i.e., more sustained responses) than those within nontonotopic penetrations (blue solid line), the distributions largely overlapped. Restricting the estimate of RPI from tonotopic penetrations to those deeper than the first site (red dashed line) shifted the distribution slightly to the left, and restricting the analysis of nontonotopic sites to those monkeys that showed tonotopy (blue dashed line) shifted the distribution slightly to the right, but considerable overlap remained.

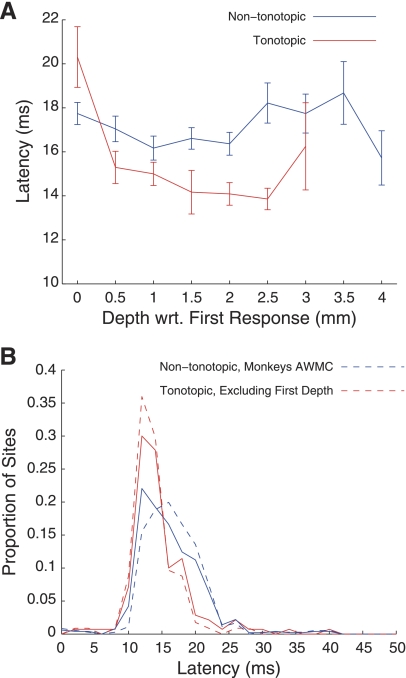

Latency of response also showed some topographic organization. More central penetrations contained sites that responded faster than more peripheral penetrations (Fig. 9). As with RPI, we also found an effect of depth within tonotopic penetrations, with shallower sites showing slower responses than those recorded at deeper locations (Fig. 10A). Across all locations, a small difference between tonotopic and nontonotopic penetrations was found (Fig. 10B; P < 0.01, t-test). Excluding the shallowest tonotopic recording and the data from monkeys in which we did not observe tonotopy slightly increased the separation between distributions of latency, but there was considerable overlap (similar to the results found for RPI). Overall, the estimates of latency are similar to those noted previously (Ryan and Miller 1978; Zwiers et al. 2004), when taking into account that latency calculations included the time it took to for the sound to reach the ear (∼4 ms; see methods).

Fig. 9.

Maps of response latency in the horizontal plane. Maps follow the format in Fig. 5, here color indicates the average latency from each penetration location. Note that the calculation of latency included the time it took for sound to reach the ear (∼4 ms).

Fig. 10.

Latency distribution for tonotopic and nontonotopic penetrations. A: average latency at each depth, relative to the first auditory recording in the penetration, for tonotopic (red) and nontonotopic (blue) penetrations. Error bars indicate SE. Distributions of latency in tonotopic and nontonotopic penetrations (B) overlapped, although tonotopic penetrations generally showed more faster (i.e., lower latency) responses. The trend persisted when data from monkeys not showing tonotopy were excluded (blue broken line) or when the shallowest recordings were excluded (red broken line).

DISCUSSION

The results from this study provide the first extensive physiological map of the auditory midbrain in the monkey. We established a small volume of tissue in which tonotopic organization was readily identifiable, surrounded by a surprisingly large region that showed no such organization. In the latter, low frequency responses prevailed, indicating a strong bias toward low frequency tones. The two functionally identifiable regions we observed likely have anatomical correlates.

Subdivisions of the IC and the Representation of Sound Frequency

Historically, the IC has been divided into a central nucleus (ICC) and surrounding regions on the lateral [lateral nucleus (LN)] and dorsal (DCIC) aspects (Morest 1964; Ramón y Cajal 1911; Rockel and Jones 1973a,b,c). Golgi impregnations have provided a thorough parcellation through the precise analysis of the spatial arrangement of both axons and dendrites, as was performed by Morest and Oliver in the cat (1984). Their study classified cells surrounding the ICC, not just those lateral and dorsal to the central nucleus, but also cells rostral, caudal, and medial to the ICC.

The distinguishing feature of ICC is a series of fibrodendritic laminae, formed by the parallel dendritic fields of disc shaped neurons (Morest 1964). The layers seem to match tuning patterns, with the most dorsolateral layers corresponding to low frequency tuned neurons, with tuning to increasing frequencies found in successively ventromedial layers [see Ehret and Schreiner (2005) for review]. ICC primarily receives ascending input from the auditory brain stem: from the cochlear nucleus [reviewed in Cant (2005)] and from the superior olivary complex and nuclei of the lateral lemniscus [reviewed in Schofield (2005)]. Descending input from auditory cortex also projects to the ICC (Andersen et al. 1980). Projections from the ICC continue up the auditory pathway where they synapse mainly on the ventral region of the medial geniculate body (MGB; Calford and Aitkin 1983).

In contrast, LN and DCIC have a more diffuse set of connections. These regions receive ascending auditory input via the ICC (Saldaña and Merchan 1992) but more weakly from brainstem sources (Aitkin et al. 1981; Coleman and Clerici 1987). DCIC and LN are more heavily innervated by auditory cortex, receiving more descending input than ICC (Andersen et al. 1980; Coleman and Clerici 1987; Diamond et al. 1969; Druga and Syka 1984a,b; Druga et al. 1997; Saldaña et al. 1996; Schofield 2009; Winer et al. 2002), In addition, LN receives nonauditory input from the somatosensory (Aitkin et al. 1978; Aitkin et al. 1981) and visual (Coleman and Clerici 1987; Cooper and Young 1976) systems. The projections from the LN and DCIC also differ from those of the ICC. DCIC and LN do project to the MGB, like the ICC does, but they mainly synapse on cells in the medial and dorsal regions (Calford and Aitkin 1983), along a purported modulatory pathway of the auditory system (Lee and Sherman 2010). These regions also send output to the SC (Kudo and Niimi 1980).

Beyond the rostral borders of the ICC one finds the rostral pole (RP) and intercollicular tegmentum (Morest and Oliver 1984). The RP is a small area that receives input from the auditory brainstem but differs from the ICC in that it sends its output primarily to the SC rather than the MGB (Harting and Van Lieshout 2000; Osen 1972). The intercollicular tegmentum is part of the mesencephalic reticular formation, and receives inputs from a variety of auditory, visual, and somatosensory sources (Lopez et al. 1999; Robards 1979; RoBards et al. 1976).

The ICC thus forms an auditory “core” region that is an obligatory stop along the ascending auditory pathway, i.e., little or no input reaches the ventral auditory thalamus without first passing through the ICC. The surrounding structures form a “shell” region (LN, DCIC, RP, and intercollicular tegmentum) that receives auditory and nonauditory input from a variety of sources and projects more diffusely.

Because of the interconnectedness of the regions of the IC as a whole, the feedback they receive from auditory cortical regions, and the reciprocity of their connections with earlier brainstem auditory structures (Coleman and Clerici 1987; Gonzalez-Hernandez et al. 1996; Hutson et al. 1991; Saldaña and Merchan 1992), it is difficult to identify the circuit underlying any particular type of response. Nevertheless, certain physiological differences have been observed in these different regions. Aitkin et al. (1975) tested tuning and binaural response properties in cat ICC, DCIC, and LN. They found that neurons in DCIC and LN showed broad tuning, or no evidence of tuning at all, and that neurons in DCIC were generally only driven by the stimulation of the contralateral ear, while LN and ICC were binaurally influenced. DCIC and LN also seem to be better driven by complex sounds, such as vocalizations, while ICC neurons show greater firing in response to presentations of pure tones (Aitkin et al. 1994).

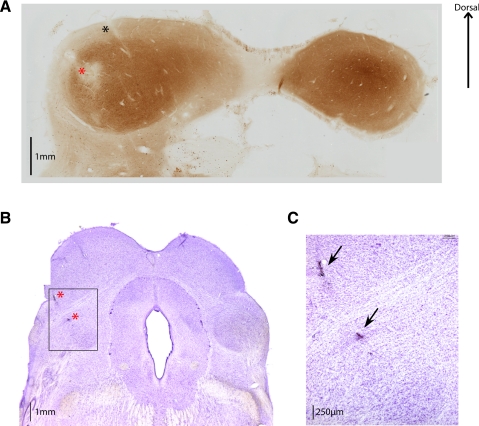

The tonotopic penetrations in our map likely passed through the ICC. ICC has exhibited clear tonotopic organization across species [e.g., rats (Clopton and Winfield 1973; Kelly et al. 1991); cats (Aitkin et al. 1975; Merzenich and Reid 1974; Rose et al. 1963); guinea pigs (Malmierca et al. 1995); mice (Stiebler and Ehret 1985); ferrets (Moore et al. 1983); owls (Knudsen and Konishi 1978); and bats (Casseday and Covey 1992; Miller et al. 2005; Poon et al. 1990; Zook et al. 1985)] and shows more sustained and short latency responses (Aitkin et al. 1994; Ryan and Miller 1978; Syka et al. 2000; Willott and Urban 1978). Figure 11A shows an electrolytic lesion placed in the middle of a tonotopic penetration in monkey W in a section stained with cytochrome oxidase. This stain marks metabolic activity, which is markedly higher in the ICC than in the surrounding area (Dezso et al. 1993). The location of the penetration in which the lesion was placed is indicated with an “X” on the map in Fig. 5.

Fig. 11.

Histological verification of recording locations. A: 60-μm coronal section from monkey W stained with cytochrome oxidase. The location of an electrolytic lesion (noted on the map in Fig. 5) is indicated with a red asterisk. A track left behind by a recording electrode, ∼1 mm medial to the lesion and following the 30° angle established by the chamber, is indicated with a black asterisk. IC central nucleus (ICC) can be visualized as the region showing a dark stain, indicative of higher metabolic activity. A section from monkey X is shown in B, in which 2 lesions were made along a penetration through the central region of recordings (the location is noted on the map in Fig. 5, and on the image with red asterisks). Sections from this monkey were 50 μm thick and stained with cresyl violet. Section containing the lesion is rostral to the one shown in A, and the SC is clearly identifiable on the dorsal part of the slide. Just deeper than the lesion the rostral pole can be found, indicating that this penetration was just anterior to the ICC. C: magnified view of the square in B. Image shown in B and C has been published previously (Porter et al. 2006).

While the evidence that the tonotopic penetrations probably passed through the ICC is strong, the converse, that the nontonotopic penetrations did not, is less clear. In monkeys E and X, we did not identify tonotopic gradients in any recording penetrations. This is not surprising in monkey E, as our entire sample was likely medial to the ICC, but tonotopic organization was expected in monkey X where the central region was well sampled. A lesion was made at a central recording location and identified near RP on a section stained with Nissl techiniques (Fig. 11, B and C). Recordings were taken caudal to the location of the lesion, in a region that corresponds to ICC, but no tonotopic penetrations were identified, even though response characteristics typical of tonotopic penetrations in other monkeys, such as a strong sustained response or short response latency, were observed at several sites in monkey X.

It is therefore possible that the strength of tonotopic organization varies across individual animals and that in monkey X it was not identifiable or that some aspect of our recording methods precluded detection of tonotopy. Improvements in our recording equipment over the course of this study may have facilitated identification of tonotopy and responses in general. After monkeys X, C, M, and E were tested but before monkeys A and W were tested, the neural recording system was upgraded and changes in software that allowed online analysis of the data were incorporated. This helped us target our recordings to the region of the IC more successfully and improved our selection of multiunit activity. Indeed, monkeys A and W showed the clearest signal-to-noise ratios. Interpretation and resolution of anatomical MRIs also improved throughout the course of the study, allowing better targeting of the IC.

Most likely, some but not all of the penetrations classified as nontonotopic passed through the ICC as well. In particular, penetrations adjacent to tonotopic locations in our map likely passed through the ICC, but only through a small part, or passed through the ICC nonperpendicularly to the tonotopic gradient. It is also possible that a portion of the ICC is not tonotopic at all but consistently favors low frequency sounds and that this low frequency bias is a feature shared in common with the surrounding shell.

It is also possible that some locations that were actually tonotopic or tuned were mischaracterized due to the relatively coarse sampling of tissue relative to the size of the IC and the use of a set of stimuli that only represent part of the macaque frequency range. Although we only sampled a subset of the primate hearing range, this is unlikely to account for the low frequency bias we observed. Very few sites responded well to frequencies in the 2- to 12-kHz range; instead most sites responded best to lower frequencies. Since we did not test with higher frequencies, we cannot rule out that they showed bimodal frequency response functions with both low and very high frequency peaks, but there is little evidence of this kind of tuning pattern in other species. More likely, there may have been nonresponsive sites at the end of tonotopic penetrations that were tuned to frequencies we did not test. The main confound produced by such an effect would be that the IC may be larger and the tonotopic stretches longer than we have been able to demonstrate.

Overall, identifying the location of any non-ICC penetrations is more challenging. Although measurements of the tonotopic region recorded fit well with estimates of the size of ICC (Paxinos et al. 2000), the auditory-responsive region surrounding tonotopic responses is much larger than anticipated, even when excluding potential ICC penetrations that were adjacent those in which tonotopy was identified. It is possible that some auditory responsive sites reflected signals from axons rather than cell bodies and that this could have expanded the apparent size of the IC. Alternatively, these data are best described as coming from a number of nearby, anatomically distinct areas, including not only DCIC/LN but also regions such as the intercollicular tegmentum and the nucleus of the brachium. The homogeneity of response characteristics (latency, temporal profile, and tuning properties) provides reason to group these data together, although it likely represents responses of both collicular and pericollicular regions.

Temporal Profile

The temporal patterns of the response also relate to those found previously. We found shorter latency and more sustained responses in tonotopic penetrations (Figs. 8B and 10B). Along tonotopic penetrations, the most dorsal recordings showed uncharacteristically slow and transient responses (Figs. 8A and 10A), consistent with the idea that electrodes passed through DCIC en route to ICC. Results regarding the temporal profile should be compared with the literature with caution, as the choice of MUA as a metric precludes the identification of individual sustained and transient type cells. Rather, the measurement of sustained and transient components in the response relates to the proportion of sustained and transient type units comprising the MUA. Our data on responses in the awake animal also likely differ from those in anesthetized animals. Anesthesia has been shown to affect the temporal profile of responses in the IC (Astl et al. 1996; Kuwada et al. 1989).

Low Frequency Bias

The most surprising aspect of our findings was the prevalence of low frequency tuning. Throughout the more transient, slower, nontonopic region we sampled, we found a strong bias toward low frequency tuning (Fig. 6). Fitzpatrick (1975) also found no evidence of high frequency tuned neurons (>2 kHz) in the shell surrounding the ICC of the squirrel monkey.

Typically, the magnification of a particular range of stimulus space corresponds with some enhanced perceptual capacity. For example, amplification of a specific frequency range, linked with sounds of ethological relevance has been seen in the auditory system of other species [e.g., owl (Köppl et al. 1993); bat (Kossl and Vater 1985); and mole (Muller et al. 1992)]. This finding is surprising in rhesus monkeys because no perceptual correlate in this frequency range has yet been established. The rhesus monkey audiogram is approximately flat from 500 Hz to 16 kHz: the monkey is at its most sensitive, and uniformly so, throughout this range [for review, see Coleman (2009)]. That a perceptual or ethological correlate may eventually be found seems possible: preliminary efforts in our laboratory to train monkeys to perform sound frequency discrimination tasks have been more successful at lower frequencies, ∼800 Hz, than at higher frequencies, ∼3 kHz (Ross and Groh 2009).

Implications for Prostheses and Other Work

Several aspects of our study have important implications for the design and placement of prosthetic devices in the IC. Chiefly, the limited extent of tonotopy, the variability in its presence or perhaps location in individual animals, and the dominance of low frequencies pose a logistical challenge. To be successful, a prosthetic device needs to access sites that encode a range of different frequencies. It may also be advantageous to target the main channels of the ascending auditory signal. If the human IC is similar to that of the monkey, then a large number of electrodes may need to be placed in a range of locations to increase the odds that some are positioned in the comparatively small volume of the IC containing neurons devoted to ascending high frequency information. Indeed, the earliest attempts at auditory midbrain implants have produced predominantly low frequency percepts at most electrode sites (Lim et al. 2008), suggesting that the challenge of finding high frequency sites may well be true in humans as well as monkeys.

Generally, our results provide a guide or context that may be of some utility for studies in which detailed mapping is not possible. Placement of prosthetic stimulating electrodes in humans is done precisely because the patient is deaf without it; thus mapping the auditory response properties before placement is not possible. Other types of work involve a trade-off between optimizing for anatomical certainty at the expense of physiological normality and vice versa. For example, the most detailed mapping studies are generally done in anesthetized animals, over the span of at most a few days, and often involve removal of the tissue overlying the IC so that the placement of the electrodes can be guided by visual inspection. Histological reconstruction is done immediately following such experiments. Such methods provide the best information about the location of recording sites, but the information about the response properties is colored by uncertainty about whether the response properties are altered by the presence of anesthetic drugs or the removal of a portion of the brain. At the other end of the spectrum are studies in which no mapping is conducted and the response properties are studied largely divorced from information about where precisely they may occur. In awake monkeys, recordings take place over months or years, making it very difficult to reconstruct the location of specific sites even if histology is conducted at the conclusion of the studies. Our study attempted to strike a middle ground between these approaches.

Our study also represents a relatively coarse sampling of the midbrain. This was necessary to accommodate the large region of auditory-responsive neurons. Our map thus describes the large-scale organization of the midbrain but cannot precisely identify boundaries or the three-dimensional shape of functionally defined regions. Such a coarse approach was required to collect a body of data that sampled the entire IC, including measurements of activity from outside the IC so that functional borders could be determined. Finer spatial sampling and additional stimulus characteristics would have added to the resolution of the map, but are unrealistic in such large scale systematic mapping. The objective methods we used for categorizing tonotopic penetrations and temporal profile of response provide metrics that can be compared across electrophysiological studies. Our results can thus be used to guide future work focused on a limited region of the IC and provide a context for interpreting organization at a smaller scale.

GRANTS

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health Grants EY-016478 (to J. M. Groh) and DC-010294 (to D. A. Bulkin).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Nate Greene, Vanessa Kennedy, Uri Werner-Reiss, and Nick Del Grosso for collecting some of the data for these experiments; Abigail Underhill, Tom Heil, and Jessi Cruger for technical support; and Nell Cant, David Larue, and Jeff Winer for performing the histology. We also thank Nell Cant, David Larue, Jeff Winer, David Fitzpatrick, Michael Platt, and Steve Mitroff for insightful comments.

REFERENCES

- Aitkin L, Tran L, Syka J. The responses of neurons in subdivisions of the inferior colliculus of cats to tonal, noise and vocal stimuli. Exp Brain Res 98: 53–64, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aitkin LM, Dickhaus H, Schult W, Zimmermann M. External nucleus of inferior colliculus: auditory and spinal somatosensory afferents and their interactions. J Neurophysiol 41: 837–847, 1978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aitkin LM, Kenyon CE, Philpott P. The representation of the auditory and somatosensory systems in the external nucleus of the cat inferior colliculus. J Comp Neurol 196: 25–40, 1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aitkin LM, Phillips SC. Is the inferior colliculus and obligatory relay in the cat auditory system? Neurosci Lett 44: 259–264, 1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aitkin LM, Webster WR, Veale JL, Crosby DC. Inferior colliculus. I. Comparison of response properties of neurons in central, pericentral, and external nuclei of adult cat. J Neurophysiol 38: 1196–1207, 1975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen RA, Snyder RL, Merzenich MM. The topographic organization of corticocollicular projections from physiologically identified loci in the AI, AII, and anterior auditory cortical fields of the cat. J Comp Neurol 191: 479–494, 1980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Astl J, Popelar J, Kvasnak E, Syka J. Comparison of response properties of neurons in the inferior colliculus of guinea pigs under different anesthetics. Audiology 35: 335–345, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calford MB, Aitkin LM. Ascending projections to the medial geniculate body of the cat: evidence for multiple, parallel auditory pathways through thalamus. J Neurosci 3: 2365–2380, 1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cant NB. Projections from the cochlear nuclear complex to the inferior colliculus. In: The Inferior Colliculus, edited by Winer JA, Schreiner CE. New York, NY: Springer, 2005, p. 115–131. [Google Scholar]

- Casseday JH, Covey E. Frequency tuning properties of neurons in the inferior colliculus of an FM bat. J Comp Neurol 319: 34–50, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clopton BM, Winfield JA. Tonotopic organization in the inferior colliculus of the rat. Brain Res 56: 355–358, 1973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman JR, Clerici WJ. Sources of projections to subdivisions of the inferior colliculus in the rat. J Comp Neurol 262: 215–226, 1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman M. What do primates hear? A meta-analysis of all known nonhuman primate behavioral audiograms. Int J Primatol 30: 55–91, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Colletti V, Shannon R, Carner M, Sacchetto L, Turazzi S, Masotto B, Colletti L. The first successful case of hearing produced by electrical stimulation of the human midbrain. Otol Neurotol 28: 39–43, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colletti V, Shannon RV, Carner M, Veronese S, Colletti L. Progress in restoration of hearing with the auditory brainstem implant. Prog Brain Res 175: 333–345, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper MH, Young PA. Cortical projections to the inferior colliculus of the cat. Exp Neurol 51: 488–502, 1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dezso A, Schwarz DW, Schwarz IE. A survey of the auditory midbrain, thalamus and forebrain in the chicken (Gallus domesticus) with cytochrome oxidase histochemistry. J Otolaryngol 22: 391–396, 1993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond IT, Jones EG, Powell TP. The projection of the auditory cortex upon the diencephalon and brain stem in the cat. Brain Res 15: 305–340, 1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Druga R, Syka J. Ascending and descending projections to the inferior colliculus in the rat. Physiol Bohemoslov 33: 31–42, 1984a. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Druga R, Syka J. Neocortical projections to the inferior colliculus in the rat. (An experimental study using anterograde degeneration techniques). Physiol Bohemoslov 33: 251–253, 1984b. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Druga R, Syka J, Rajkowska G. Projections of auditory cortex onto the inferior colliculus in the rat. Physiol Res 46: 215–222, 1997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehret G, Schreiner CE. Spectral and intensity coding in the auditory midbrain. In: The Inferior Colliculus, edited by Winer JA, Schreiner CE. New York, NY: Springer, 2005, p. 312–345. [Google Scholar]

- FitzPatrick KA. Cellular architecture and topographic organization of the inferior colliculus of the squirrel monkey. J Comp Neurol 164: 185–207, 1975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Hernandez T, Mantolan-Sarmiento B, Gonzalez-Gonzalez B, Perez-Gonzalez H. Sources of GABAergic input to the inferior colliculus of the rat. J Comp Neurol 372: 309–326, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groh JM, Kelly KA, Underhill AM. A monotonic code for sound azimuth in primate inferior colliculus. J Cogn Neurosci 15: 1217–1231, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groh JM, Trause AS, Underhill AM, Clark KR, Inati S. Eye position influences auditory responses in primate inferior colliculus. Neuron 29: 509–518, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harting JK, Van Lieshout DP. Projections from the rostral pole of the inferior colliculus to the cat superior colliculus. Brain Res 881: 244–247, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutson KA, Glendenning KK, Masterton RB. Acoustic chiasm. IV: Eight midbrain decussations of the auditory system in the cat. J Comp Neurol 312: 105–131, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jay MF, Sparks DL. Auditory receptive fields in primate superior colliculus shift with changes in eye position. Nature 309: 345–347, 1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jay MF, Sparks DL. Sensorimotor integration in the primate superior colliculus. I. Motor convergence. J Neurophysiol 57: 22–34, 1987a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jay MF, Sparks DL. Sensorimotor integration in the primate superior colliculus. II. Coordinates of auditory signals. J Neurophysiol 57: 35–55, 1987b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Judge SJ, Richmond BJ, Chu FC. Implantation of magnetic search coils for measurement of eye position: an improved method. Vision Res 20: 535–538, 1980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalwani RM, Bloy L, Elliott MA, Gold JI. A method for localizing microelectrode trajectories in the macaque brain using MRI. J Neurosci Methods 176: 104–111, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JB, Glenn SL, Beaver CJ. Sound frequency and binaural response properties of single neurons in rat inferior colliculus. Hear Res 56: 273–280, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knudsen EI, Konishi M. Space and frequency are represented separately in auditory midbrain of the owl. J Neurophysiol 41: 870–884, 1978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Köppl C, Gleich O, Manley G. An auditory fovea in the barn owl cochlea. J Comp Physiol A 171: 695–704, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Kossl M, Vater M. The cochlear frequency map of the mustache bat, Pteronotus parnellii. J Comp Physiol A 157: 687–697, 1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudo M, Niimi K. Ascending projections of the inferior colliculus in the cat: an autoradiographic study. J Comp Neurol 191: 545–556, 1980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuwada S, Batra R, Stanford TR. Monaural and binaural response properties of neurons in the inferior colliculus of the rabbit: effects of sodium pentobarbital. J Neurophysiol 61: 269–282, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CC, Sherman SM. Drivers and modulators in the central auditory pathways. Front Neurosci 4: 79, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim HH, Anderson DJ. Auditory cortical responses to electrical stimulation of the inferior colliculus: implications for an auditory midbrain implant. J Neurophysiol 96: 975–988, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim HH, Anderson DJ. Spatially distinct functional output regions within the central nucleus of the inferior colliculus: implications for an auditory midbrain implant. J Neurosci 27: 8733–8743, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim HH, Lenarz M, Lenarz T. Auditory midbrain implant: a review. Trends Amplif 13: 149–180, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim HH, Lenarz T, Anderson DJ, Lenarz M. The auditory midbrain implant: effects of electrode location. Hear Res 242: 74–85, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez DE, Saldaña E, Nodal FR, Merchan MA, Warr WB. Projections of cochlear root neurons, sentinels of the rat auditory pathway. J Comp Neurol 415: 160–174, 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malmierca MS, Rees A, Le Beau FE, Bjaalie JG. Laminar organization of frequency-defined local axons within and between the inferior colliculi of the guinea pig. J Comp Neurol 357: 124–144, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merzenich MM, Reid MD. Representation of the cochlea within the inferior colliculus of the cat. Brain Res 77: 397–415, 1974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller KE, Casseday JH, Covey E. Relation between intrinsic connections and isofrequency contours in the inferior colliculus of the big brown bat, Eptesicus fuscus. Neuroscience 136: 895–905, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore BCJ. An Introduction to the Psychology of Hearing. Bingley, UK: Emerald, vol. XIIII, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Moore DR, Semple MN, Addison PD. Some acoustic properties of neurones in the ferret inferior colliculus. Brain Res 269: 69–82, 1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morest DK. Laminar structure of inferior colliculus of cat (Abstract). In American Association of Anatomists 77th Session; 1964 Mar 31-Apr 3; Denver, CO. [Google Scholar]

- Morest DK, Oliver DL. The neuronal architecture of the inferior colliculus in the cat: defining the functional anatomy of the auditory midbrain. J Comp Neurol 222: 209–236, 1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller M, Laube B, Burda H, Bruns V. Structure and function of the cochlea in the African mole rat (Cryptomys hottentotus): evidence for a low frequency acoustic fovea. J Comp Physiol A 171: 469–476, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osen KK. Projection of the cochlear nuclei on the inferior colliculus in the cat. J Comp Neurol 144: 355–372, 1972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Huang XF, Toga AW. The Rhesus Monkey Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. San Diego, CA: Academic, 2000, p. 163. [Google Scholar]

- Pfingst BE, Hienz R, Miller J. Reaction-time procedure for measurement of hearing. II. Threshold functions. J Acoust Soc Am 57: 431–436, 1975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfingst BE, Laycock J, Flammino F, Lonsbury-Martin B, Martin G. Pure tone thresholds for the rhesus monkey. Hear Res 1: 43–47, 1978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poon PW, Sun X, Kamada T, Jen PH. Frequency and space representation in the inferior colliculus of the FM bat, Eptesicus fuscus. Exp Brain Res 79: 83–91, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Populin LC, Tollin DJ, Yin TC. Effect of eye position on saccades and neuronal responses to acoustic stimuli in the superior colliculus of the behaving cat. J Neurophysiol 92: 2151–2167, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter KK, Metzger RR, Groh JM. Representation of eye position in primate inferior colliculus. J Neurophysiol 95: 1826–1842, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter KK, Metzger RR, Groh JM. Visual- and saccade-related signals in the primate inferior colliculus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 17855–17860, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramón Y, Cajal S. Histologie du Système Nerveux de l'Homme et des Vertébrés, Paris: A. Maloine, vol. 1, 1911, p. 997. [Google Scholar]

- Robards MJ. Somatic neurons in the brainstem and neocortex projecting to the external nucleus of the inferior colliculus: an anatomical study in the opossum. J Comp Neurol 184: 547–565, 1979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RoBards MJ, Watkins DW, III, Masterton RB. An anatomical study of some somesthetic afferents to the intercollicular terminal zone of the midbrain of the opossum. J Comp Neurol 170: 499–524, 1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson DA. A method of measuring eye movement using a scleral search coil in a magnetic field. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng 10: 137–145, 1963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockel AJ, Jones EG. The neuronal organization of the inferior colliculus of the adult cat. I. The central nucleus. J Comp Neurol 147: 11–60, 1973a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockel AJ, Jones EG. The neuronal organization of the inferior colliculus of the adult cat. II. The pericentral nucleus. J Comp Neurol 149: 301–334, 1973b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockel AJ, Jones EG. Observations on the fine structure of the central nucleus of the inferior colliculus of the cat. J Comp Neurol 147: 61–92, 1973c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose JE, Greenwood DD, Goldberg JM, Hind JE. Some discharge characteristics of single neurons in the inferior colliculus of the cat. I. Tonotopical organization, relation of spike-counts to tone intensity, and firing patterns of single elements. J Neurophysiol 26: 294–320, 1963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross DA, Groh JM. Performance of monkeys on a frequency discrimination task involving pitch direction (higher vs. lower) judgments. In: Society for Neuroscience Annual Meeting Chicago, IL: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan A, Miller J. Single unit responses in the inferior colliculus of the awake and performing rhesus monkey. Exp Brain Res 32: 389–407, 1978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saldaña E, Feliciano M, Mugnaini E. Distribution of descending projections from primary auditory neocortex to inferior colliculus mimics the topography of intracollicular projections. J Comp Neurol 371: 15–40, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saldaña E, Merchan MA. Intrinsic and commissural connections of the rat inferior colliculus. J Comp Neurol 319: 417–437, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schofield BR. Projections to the inferior colliculus from layer VI cells of auditory cortex. Neuroscience 159: 246–258, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schofield BR. Superior olivary complex and lateral lemniscal connections of the auditory midbrain. In: The Inferior Colliculus, edited by Winer JA, Schreiner CE. New York, NY: Springer, 2005, p. 132–154. [Google Scholar]

- Stebbins WC, Green S, Miller FL. Auditory sensitivity of the monkey. Science 153: 1646–1647, 1966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stiebler I, Ehret G. Inferior colliculus of the house mouse. I. A quantitative study of tonotopic organization, frequency representation, and tone-threshold distribution. J Comp Neurol 238: 65–76, 1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syka J, Popelar J, Kvasnak E, Astl J. Response properties of neurons in the central nucleus and external and dorsal cortices of the inferior colliculus in guinea pig. Exp Brain Res 133: 254–266, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wessberg J, Stambaugh CR, Kralik JD, Beck PD, Laubach M, Chapin JK, Kim J, Biggs SJ, Srinivasan MA, Nicolelis MAL. Real-time prediction of hand trajectory by ensembles of cortical neurons in primates. Nature 408: 361–365, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willott JF, Urban GP. Response properties of neurons in nuclei of the mouse inferior colliculus. J Comp Physiol A 127: 175–184, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Winer JA, Chernock ML, Larue DT, Cheung SW. Descending projections to the inferior colliculus from the posterior thalamus and the auditory cortex in rat, cat, and monkey. Hear Res 168: 181–195, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zook JM, Winer JA, Pollak GD, Bodenhamer RD. Topology of the central nucleus of the mustache bat's inferior colliculus: correlation of single unit properties and neuronal architecture. J Comp Neurol 231: 530–46, 1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwiers MP, Versnel H, Van Opstal AJ. Involvement of monkey inferior colliculus in spatial hearing. J Neurosci 24: 4145–4156, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.